Development of QSAR Models and Web Applications for Predicting hDHFR Inhibitor Bioactivity Using Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

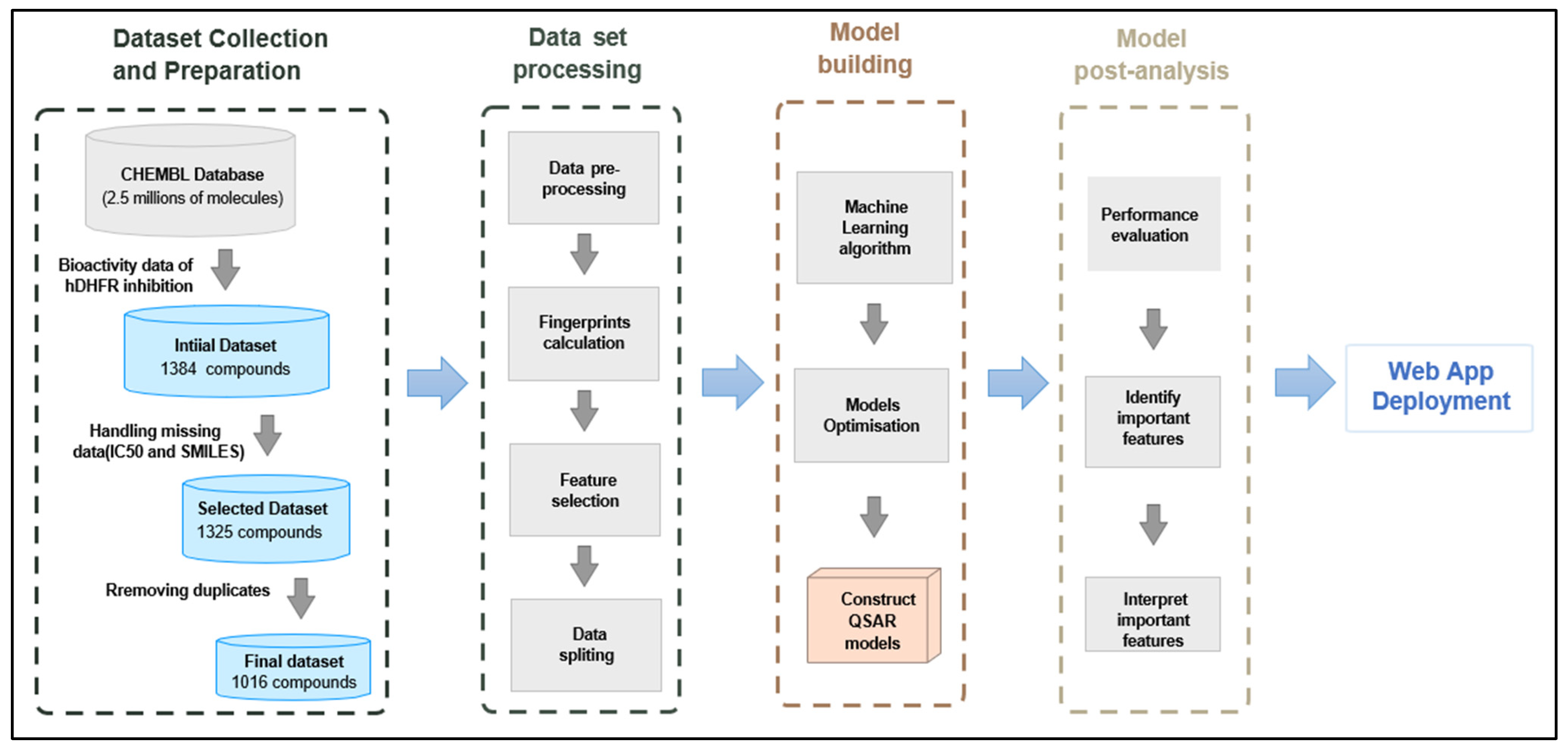

2.1. Data Collection and Preparation

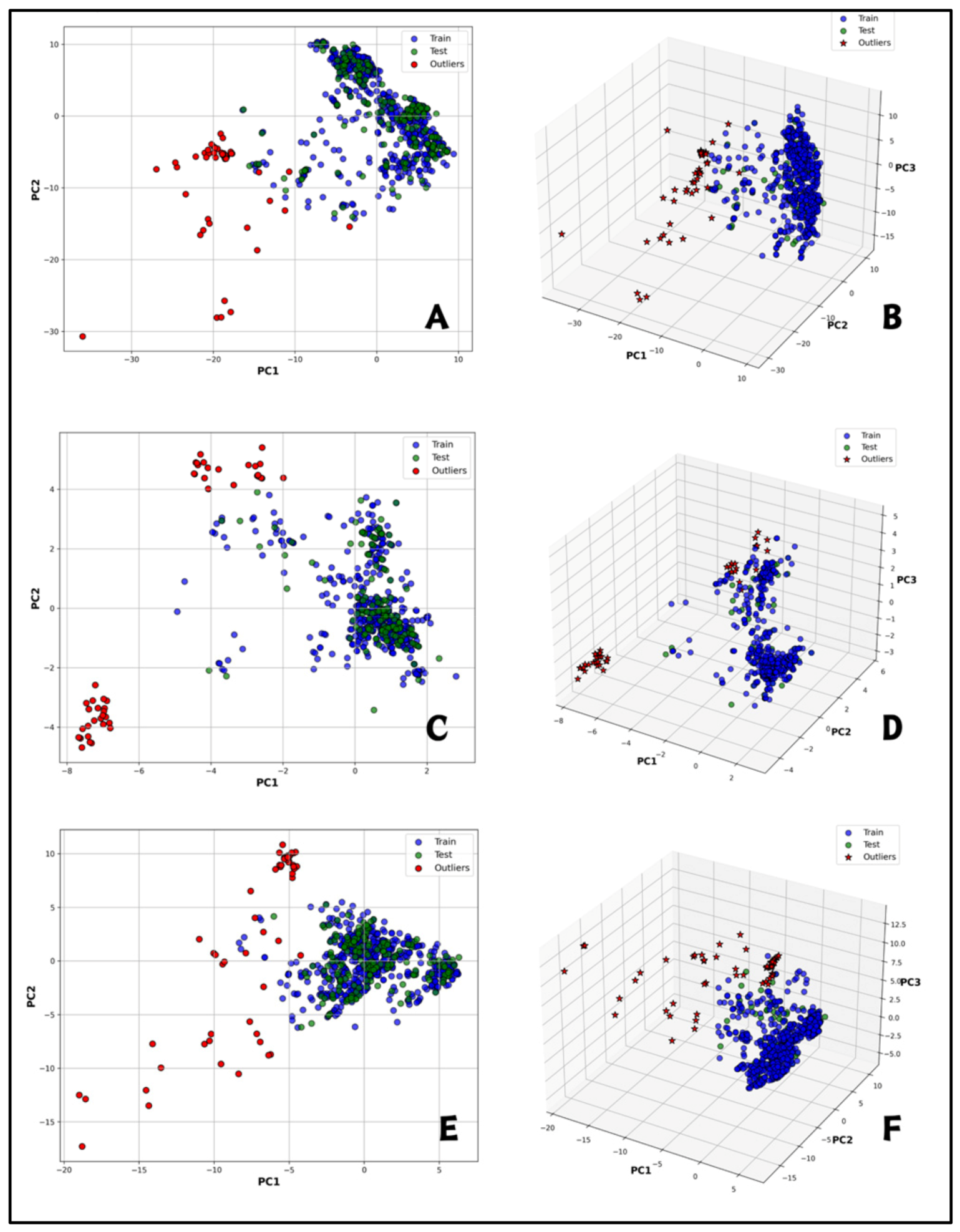

2.2. Exploratory Data Analysis

2.3. Molecular Feature Exploration

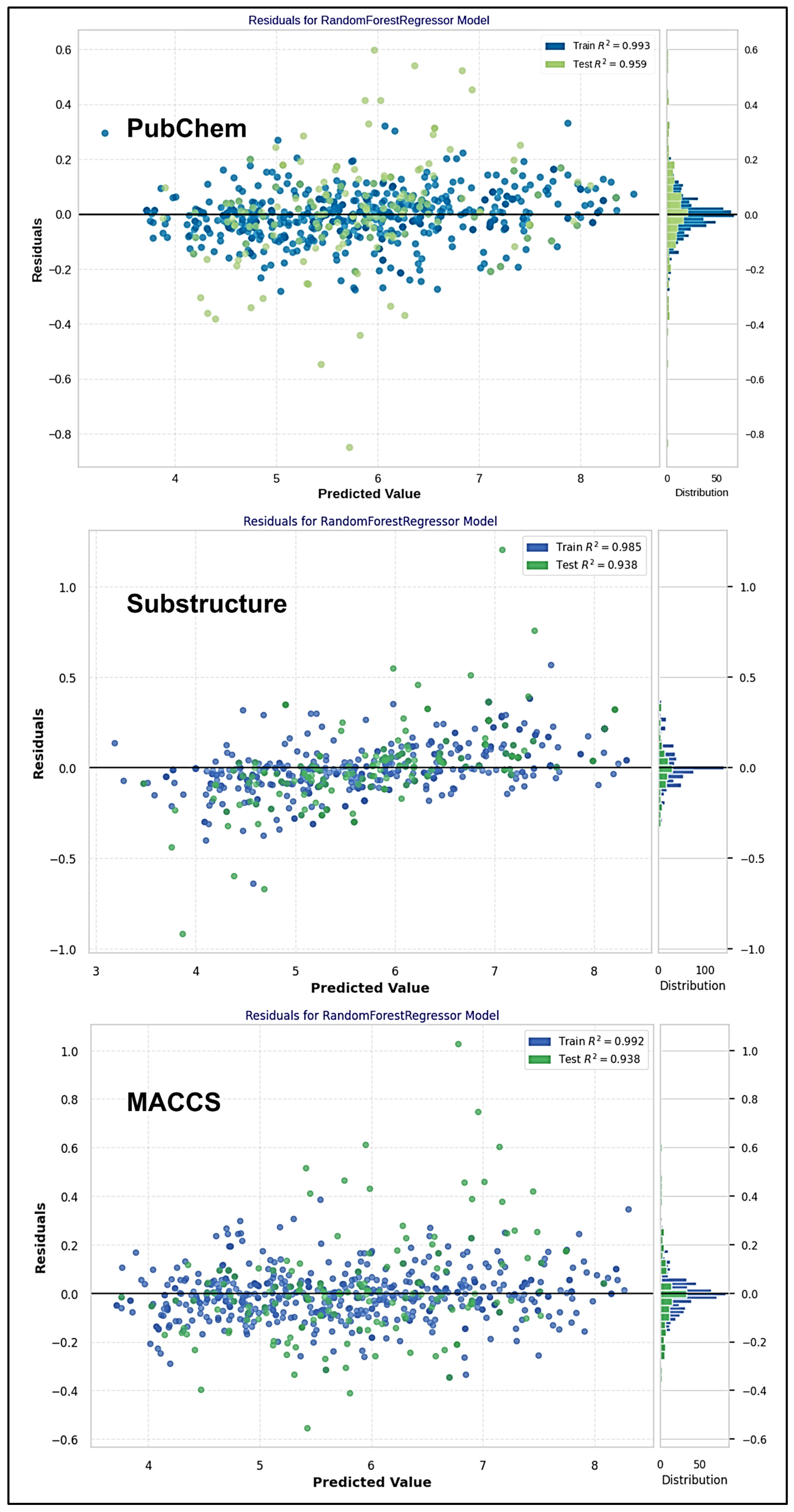

2.4. ML-QSAR Model Optimization

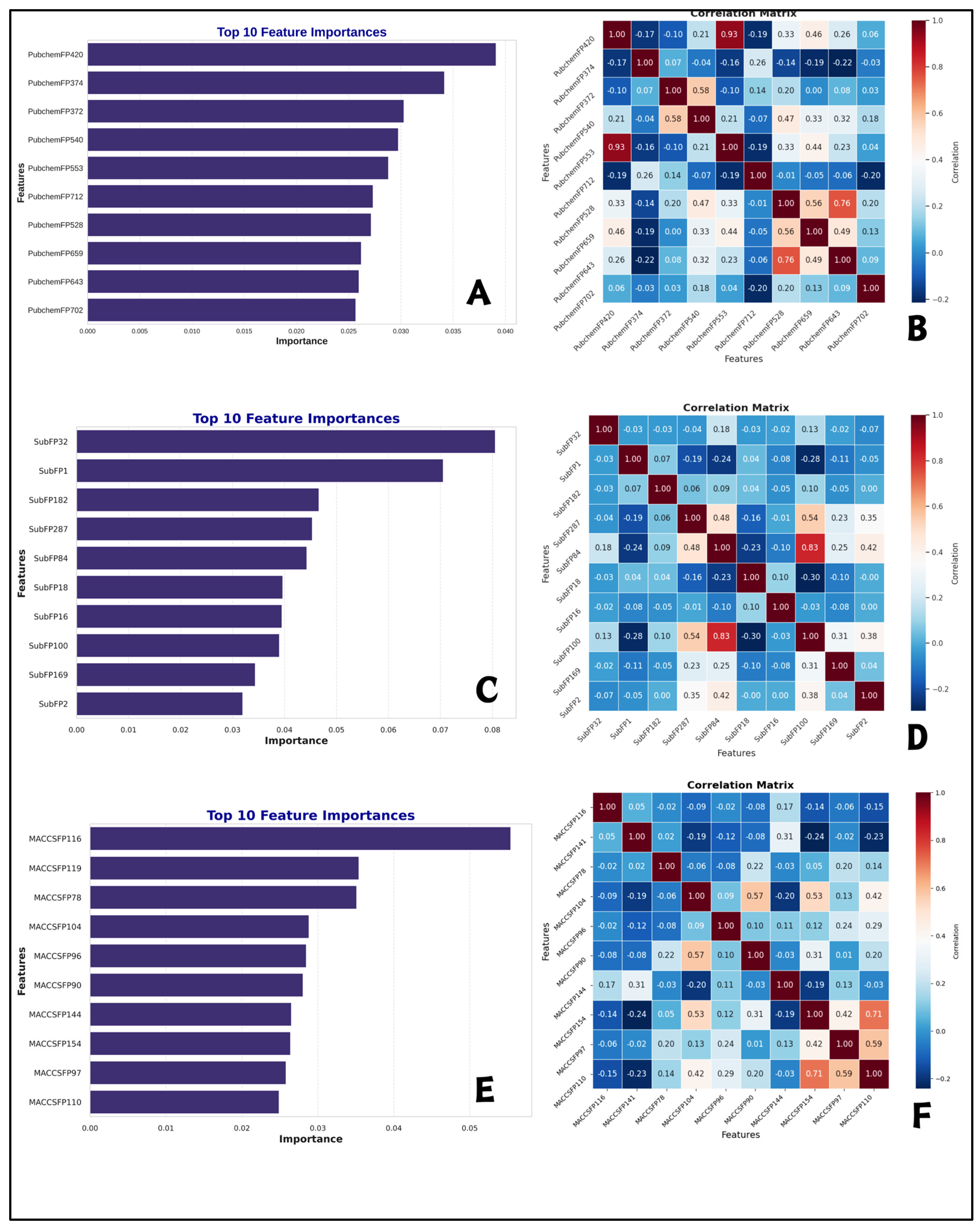

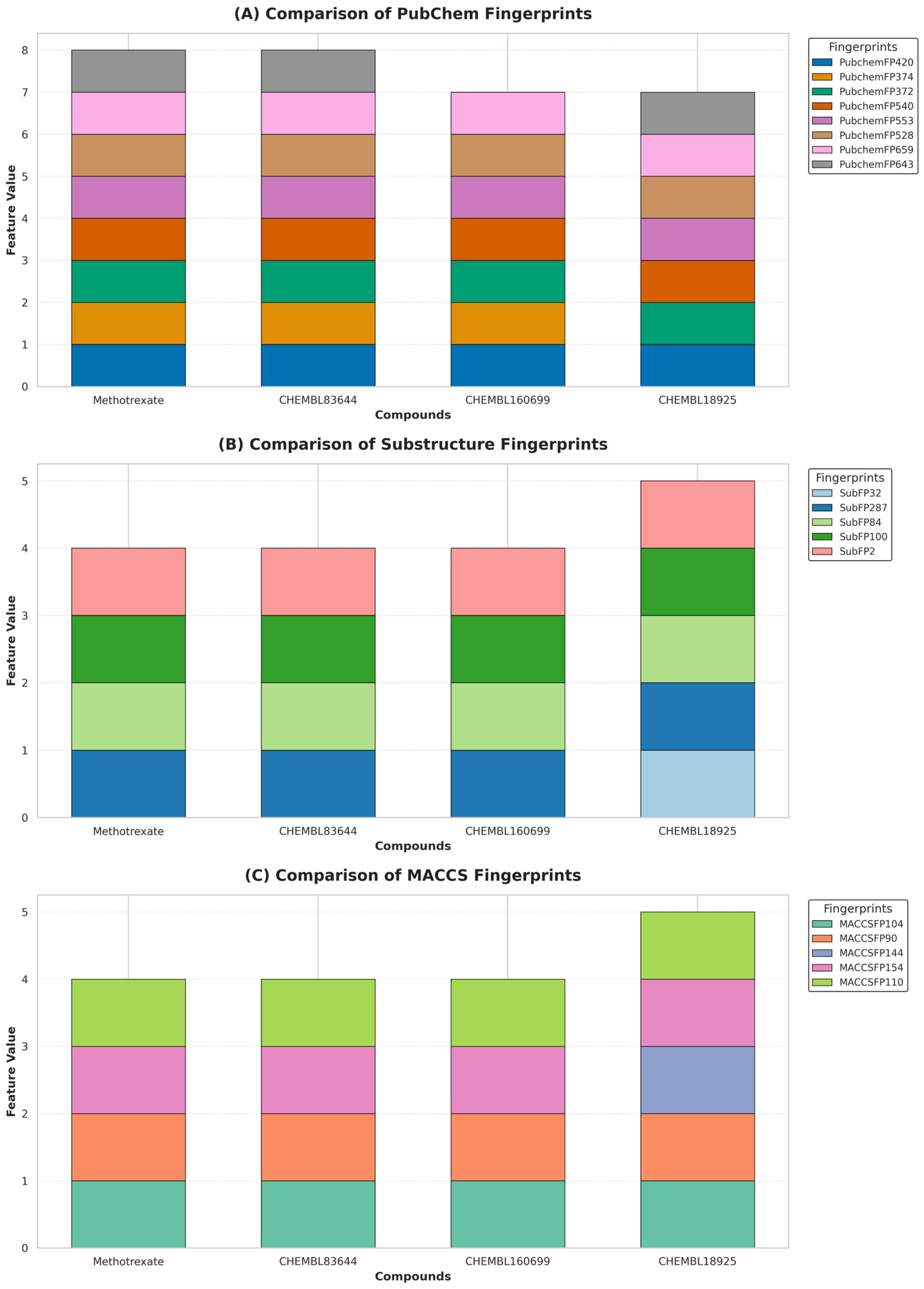

2.5. Interpretation of ML-QSAR Models

2.6. Web Application Deployment

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

3.2. Descriptors Calculation and Feature Selection

3.3. Data Splitting

3.4. ML-QSAR Models Optimization and Training

3.5. Validation and Interpretation of the ML-QSAR Models

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Applicability Domain |

| ChEMBL | European Molecular Biology Laboratory Chemical Database |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FPs | Fingerprints |

| hDHFR | Human dihydrofolate reductase |

| IC50 | Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| MACCSFP | MACCS Fingerprint |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| ML-QSAR | Machine Learning-based Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PubChemFP | PubChem Fingerprints |

| pIC50 | Negative Logarithmic Scale of IC50 |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination (R-squared) |

| RFE | Recursive Feature Elimination |

| RFR | Random Forest Regression |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| THF | Tetrahydrofolate |

| SMILES | Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System |

| SubFP | Substructure Fingerprints |

| RF-FI | Random Forest Feature Importance |

References

- de la Fuente, M.; Lombardero, L.; Gómez-González, A.; Solari, C.; Angulo-Barturen, I.; Acera, A.; Vecino, E.; Astigarraga, E.; Barreda-Gómez, G. Enzyme Therapy: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrohily, W.D.; Habib, M.E.; El-Messery, S.M.; Alqurshi, A.; El-Subbagh, H.; Habib, E.-S.E. Antibacterial, Antibiofilm and Molecular Modeling Study of Some Antitumor Thiazole Based Chalcones as a New Class of DHFR Inhibitors. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 136, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertino, J.R. Cancer Research: From Folate Antagonism to Molecular Targets. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2009, 22, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, B.I.; Dicker, A.P.; Bertino, J.R. Dihydrofolate Reductase as a Therapeutic Target. FASEB J. 1990, 4, 2441–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.M.; Mostafa, S.M.; Salama, I.; El-Sabbagh, O.I.; Hegazy, W.A.; Ibrahim, T.S. Human Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibition Effect of 1-Phenylpyrazolo [3, 4–d] Pyrimidines: Synthesis, Antitumor Evaluation and Molecular Modeling Study. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 129, 106207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.N.; Tate, C.J.; Ridgway, M.C.; Saliba, K.J.; Kirk, K.; Maier, A.G. Human Dihydrofolate Reductase Influences the Sensitivity of the Malaria Parasite Plasmodium Falciparum to Ketotifen—A Cautionary Tale in Screening Transgenic Parasites. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2016, 6, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Qiao, W.; An, Q.; Yang, T.; Luo, Y. Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitors for Use as Antimicrobial Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 195, 112268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassi, R.; Oumarou, C.S.; Burini, A.; Dolmella, A.; Micozzi, D.; Vincenzetti, S.; Pucciarelli, S. A Study on the Inhibition of Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR) from Escherichia Coli by Gold(I) Phosphane Compounds. X-Ray Crystal Structures of (4,5-Dichloro-1H-Imidazolate-1-Yl)-Triphenylphosphane-Gold(I) and (4,5-Dicyano-1H-Imidazolate-1-Yl)-Triphenylphosphane-Gold(I). Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 3043–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Yang, X. Low Folate Levels Are Associated with Methylation-Mediated Transcriptional Repression of miR-203 and miR-375 during Cervical Carcinogenesis. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 3863–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagner, N.; Joerger, M. Cancer Chemotherapy: Targeting Folic Acid Synthesis. Cancer Manag. Res. 2010, 2, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, C.; Wilson, M.; Klinger, C.M.; Franklin, M.; Oler, E.; Wilson, A.; Pon, A.; Cox, J.; Chin, N.E.; Strawbridge, S.A.; et al. DrugBank 6.0: The DrugBank Knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1265–D1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawser, S.; Lociuro, S.; Islam, K. Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitors as Antibacterial Agents. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 71, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, P.; Teli, G.; Gill, R.K.; Narang, R.K. An Insight into Synthetic Strategies and Recent Developments of Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitors. Chem. Sel. 2021, 6, 12101–12145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulhafiz, N.A.; Teoh, T.-C.; Chin, A.-V.; Chang, S.-W. Drug Repurposing Using Artificial Intelligence, Molecular Docking, and Hybrid Approaches: A Comprehensive Review in General Diseases vs Alzheimer’s Disease. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2025, 261, 108604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Er-rajy, M.; El fadili, M.; Mujwar, S.; Imtara, H.; Al kamaly, O.; Zuhair Alshawwa, S.; Nasr, F.A.; Zarougui, S.; Elhallaoui, M. Design of Novel Anti-Cancer Agents Targeting COX-2 Inhibitors Based on Computational Studies. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Manoharan, A.; Jayalakshmi, J.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; Mahdi, W.A.; Alshehri, S.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Pappachen, L.K.; Zachariah, S.M.; Aneesh, T.P.; et al. Exploiting Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors through a Combined 3-D Pharmacophore Modeling, QSAR, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Investigation. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 9513–9529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canakdag, M.; Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Kundu, S.; Sahin, D.; İlhan, İ.Ö.; Alhag, S.K.; Al-Shuraym, L.A.; Akkoc, S. Comprehensive Evaluation of Purine Analogues: Cytotoxic and Antioxidant Activities, Enzyme Inhibition, DFT Insights, and Molecular Docking Analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1323, 140798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, Z.; Zhao, B.; Su, X.; Li, G.; Hu, L. DeepHIV: A Sequence-Based Deep Learning Model for Predicting HIV-1 Protease Cleavage Sites. IEEE Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2025; [online]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er-rajy, M.; El Fadili, M.; Hadni, H.; Mrabti, N.N.; Zarougui, S.; Elhallaoui, M. 2D-QSAR Modeling, Drug-Likeness Studies, ADMET Prediction, and Molecular Docking for Anti-Lung Cancer Activity of 3-Substituted-5-(Phenylamino) Indolone Derivatives. Struct. Chem. 2022, 33, 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fadili, M.; Er-rajy, M.; Ali Eltayb, W.; Kara, M.; Imtara, H.; Zarougui, S.; Al-Hoshani, N.; Hamadi, A.; Elhallaoui, M. An In-Silico Investigation Based on Molecular Simulations of Novel and Potential Brain-Penetrant GluN2B NMDA Receptor Antagonists as Anti-Stroke Therapeutic Agents. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2024, 42, 6174–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er-rajy, M.; Fadili, M.E.; Mujwar, S.; Lenda, F.Z.; Zarougui, S.; Elhallaoui, M. QSAR, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation–Based Design of Novel Anti-Cancer Drugs Targeting Thioredoxin Reductase Enzyme. Struct. Chem. 2023, 34, 1527–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vivo, M.; Masetti, M.; Bottegoni, G.; Cavalli, A. Role of Molecular Dynamics and Related Methods in Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4035–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmaso, V.; Moro, S. Bridging Molecular Docking to Molecular Dynamics in Exploring Ligand-Protein Recognition Process: An Overview. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzione, F.; Giangreco, I.; Cole, J.C. Use of Molecular Docking Computational Tools in Drug Discovery. Prog. Med. Chem. 2021, 60, 273–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Soujeh, Z.; Safaie, N.; Moradi, S.; Abbod, M.; Sharifi, R.; Mojerlou, S.; Mokhtassi-Bidgoli, A. New Binary Mixtures of Fungicides against Macrophomina phaseolina: Machine Learning-Driven QSAR, Read-across Prediction, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Chemosphere 2024, 366, 143533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.-M.; Wang, L.; Zhao, B.-W.; Su, X.-R.; You, Z.-H.; Huang, D.-S. Integrating Transformer and Graph Attention Network for circRNA-miRNA Interaction Prediction. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2025, 29, 6105–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carracedo-Reboredo, P.; Liñares-Blanco, J.; Rodríguez-Fernández, N.; Cedrón, F.; Novoa, F.J.; Carballal, A.; Maojo, V.; Pazos, A.; Fernandez-Lozano, C. A Review on Machine Learning Approaches and Trends in Drug Discovery. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 4538–4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Ghosh, I.; Jayaprakash, V.; Jayapalan, S. Building a ML-Based QSAR Model for Predicting the Bioactivity of Therapeutically Active Drug Class with Imidazole Scaffold. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024, 11, 100148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cardoso-Silva, J.; Kelly, J.M.; Delves, M.J.; Furnham, N.; Papageorgiou, L.G.; Tsoka, S. Optimisation-Based Modelling for Explainable Lead Discovery in Malaria. Artif. Intell. Med. 2024, 147, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Xiong, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Jia, Q.; Shang, Q.; Yan, F. Accurate Forecasting of Bioconcentration Factor by Incorporating Quantum Chemical Method in the QSAR Model. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odugbemi, A.I.; Nyirenda, C.; Christoffels, A.; Egieyeh, S.A. Artificial Intelligence in Antidiabetic Drug Discovery: The Advances in QSAR and the Prediction of α-Glucosidase Inhibitors. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 2964–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Kumar, P.; Sindhu, J.; Devi, M.; Kumar, A.; Lal, S.; Singh, D. Parsing Structural Fragments of Thiazolidin-4-One Based α-Amylase Inhibitors: A Combined Approach Employing in Vitro Colorimetric Screening and GA-MLR Based QSAR Modelling Supported by Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulation and ADMET Studies. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 157, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zong, C.; Chen, S.; Chu, J.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, H. Machine Learning-Driven QSAR Models for Predicting the Cytotoxicity of Five Common Microplastics. Toxicology 2024, 508, 153918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Roy, K. Development of Hybrid Models by the Integration of the Read-across Hypothesis with the QSAR Framework for the Assessment of Developmental and Reproductive Toxicity (DART) Tested According to OECD TG 414. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 13, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Nie, F.; Gao, Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Z.; Qu, A. Studies on QSAR Models for the Anti-Virus Effect of Oseltamivir Derivatives Targeting H5N1 Based on Mix-Kernel Support Vector Machine. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2024, 261, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, L.; Ijaz, M.H.; Zaki, Z.I.; Khalifa, M.E.; Shafiq, Z.; Zubair, Z.; Sultan, N.; Saeed Ashraf Janjua, M.R. Data Driven Design of Dyes with High Dielectric Constant for Efficient Optoelectronics. J. Solid State Chem. 2025, 343, 125169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani Rad, M.N.; Behrouz, S.; Charbaghi, M.; Behrouz, M.; Zarenezhad, E.; Ghanbariasad, A. Design, Synthesis, Anticancer and in Silico Assessment of 8-Caffeinyl Chalcone Hybrid Conjugates. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 26674–26693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubus, M. The Problem of Redundant Variables in Random Forests. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Oeconomica 2018, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Anand, R.; Wang, M. Maximum Relevance and Minimum Redundancy Feature Selection Methods for a Marketing Machine Learning Platform. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA), Washington, DC, USA, 5–8 October 2019; IEEE: Washington, DC, USA, October 2019; pp. 442–452. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Bhowmik, R.; Oh, J.M.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Al-Serwi, R.H.; Kim, H.; Mathew, B. Machine Learning Driven Web-Based App Platform for the Discovery of Monoamine Oxidase B Inhibitors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Lu, Y. Bias-Corrected Random Forests in Regression. J. Appl. Stat. 2012, 39, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nantasenamat, C.; Biswas, A.; Nápoles-Duarte, J.M.; Parker, M.I.; Dunbrack, R.L. Chapter 27—Building Bioinformatics Web Applications with Streamlit. In Cheminformatics, QSAR and Machine Learning Applications for Novel Drug Development; Roy, K., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 679–699. ISBN 978-0-443-18638-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fjodorova, N.; Novich, M.; Vrachko, M.; Smirnov, V.; Kharchevnikova, N.; Zholdakova, Z.; Novikov, S.; Skvortsova, N.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V.; et al. Directions in QSAR Modeling for Regulatory Uses in OECD Member Countries, EU and in Russia. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part C 2008, 26, 201–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Nuwar, M.; Dahadha, A.A.; Hourani, W.; Abu-Halaweh, M.M.; Khalili, F.; Almustafa, E. Computational and Experimental Insights into the Anticancer Activity of Benzylidene Amino Benzoate Derivatives: A Study Based on Docking, DFT, and in Vitro Assays. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1337, 142144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Dixit, S.; Ahmad, R.; Raza, S.; Azad, I.; Joshi, S.; Khan, A.R. Molecular Docking, PASS Analysis, Bioactivity Score Prediction, Synthesis, Characterization and Biological Activity Evaluation of a Functionalized 2-Butanone Thiosemicarbazone Ligand and Its Complexes. J. Chem. Biol. 2017, 10, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Shirts, M.R.; Straub, A.P. Molecular Fingerprint-Aided Prediction of Organic Solute Rejection in Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 705, 122927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Ming, Z.; Li, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, H.; et al. Molecular Fingerprint and Machine Learning Enhance High-Performance MOFs for Mustard Gas Removal. iScience 2024, 27, 110042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Zhu, L. Understanding the Phytotoxic Effects of Organic Contaminants on Rice through Predictive Modeling with Molecular Descriptors: A Data-Driven Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 134953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisongkram, T.; Khamtang, P.; Weerapreeyakul, N. Prediction of KRASG12C Inhibitors Using Conjoint Fingerprint and Machine Learning-Based QSAR Models. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2023, 122, 108466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Li, L.; Shi, Z.; Liang, H.; Li, S.; Qiao, Z. Molecular-Fingerprint Machine-Learning-Assisted Design and Prediction for High-Performance MOFs for Capture of NMHCs from Air. Adv. Powder Mater. 2022, 1, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Liu, L.; Yang, T.; Yang, P.; Zhao, J.; Arkin, I.T.; Liu, H. Predicting the Reproductive Toxicity of Chemicals Using Ensemble Learning Methods and Molecular Fingerprints. Toxicol. Lett. 2021, 340, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Ding, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Cui, C.; Zhu, T.; Chen, K.; Xiang, P.; Luo, X. Application of Ensemble Learning for Predicting GABAA Receptor Agonists. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 169, 107958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, K.; Yu, B.; Wan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tang, F.; Li, X. Development of Organic Aggregation-Induced Emission Fluorescent Materials Based on Machine Learning Models and Experimental Validation. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1317, 139126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y. Deep Learning Algorithm Based on Molecular Fingerprint for Prediction of Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Toxicology 2024, 502, 153736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Tian, R.; Li, Z.; Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Sun, W. Data Driven Toxicity Assessment of Organic Chemicals against Gammarus Species Using QSAR Approach. Chemosphere 2023, 328, 138433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, R.; Wodaczek, F.; Del Tatto, V.; Cheng, B.; Laio, A. Automatic Feature Selection and Weighting in Molecular Systems Using Differentiable Information Imbalance. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Peng, Y.; Hu, L. A Multilayer Stacking Method Base on RFE-SHAP Feature Selection Strategy for Recognition of Driver’s Mental Load and Emotional State. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawarkar, R.D.; Khan, A.; Mali, S.N.; Deshmukh, P.K.; Ingle, R.G.; Al-Hussain, S.A.; Al-Mutairi, A.A.; Zaki, M.E.A. Cheminformatics-Driven Prediction of BACE-1 Inhibitors: Affinity and Molecular Mechanism Exploration. Chem. Phys. Impact 2024, 9, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, S.; Zhao, L.; Dong, X. Application of Artificial Intelligence to Quantitative Structure–Retention Relationship Calculations in Chromatography. J. Pharm. Anal. 2025, 15, 101155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobre, A.D.F.; Ara, A.; Alves, A.C.; Maia Neto, M.; Fachi, M.M.; Beca, L.S.D.A.B.; Tonin, F.S.; Pontarolo, R. Identifying 124 New Anti-HIV Drug Candidates in a 37 Billion-Compound Database: An Integrated Approach of Machine Learning (QSAR), Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2024, 250, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, T.; Bond, T.; Gan, Y. Development of Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) Model for Disinfection Byproduct (DBP) Research: A Review of Methods and Resources. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 299, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.M. Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationships. In Comprehensive Medicinal Chemistry III; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 379–392. ISBN 978-0-12-803201-5. [Google Scholar]

- Gissi, A.; Tcheremenskaia, O.; Bossa, C.; Battistelli, C.L.; Browne, P. The OECD (Q)SAR Assessment Framework: A Tool for Increasing Regulatory Uptake of Computational Approaches. Comput. Toxicol. 2024, 31, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colucci, R.; Mahgoub, I. Generalizable Solar Irradiance Prediction for Battery Operation Optimization in IoT-Based Microgrid Environments. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Xiao, M. Latent Feature Learning via Autoencoder Training for Automatic Classification Configuration Recommendation. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 261, 110218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillone, B.; Danov, S.; Sumper, A.; Cipriano, J.; Mor, G. A Review of Deterministic and Data-Driven Methods to Quantify Energy Efficiency Savings and to Predict Retrofitting Scenarios in Buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, H.A.; Kalakech, A.; Steiti, A. Random Forest Algorithm Overview. Babylon. J. Mach. Learn. 2024, 2024, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; Li, D. Comparison of Random Forest, Support Vector Machine and Back Propagation Neural Network for Electronic Tongue Data Classification: Application to the Recognition of Orange Beverage and Chinese Vinegar. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 177, 970–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Lai, W.; Li, M.; Feng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, T.; Tang, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, H. The Detonation Heat Prediction of Nitrogen-Containing Compounds Based on Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Combined with Random Forest (RF). Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2021, 213, 104249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rights, J.D.; Sterba, S.K. R-Squared Measures for Multilevel Models with Three or More Levels. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2023, 58, 340–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) or Mean Absolute Error (MAE)?—Arguments against Avoiding RMSE in the Literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, N.; Gupta, R.; Keserwani, P.K.; Govil, M.C. Air Quality Index Prediction Using an Effective Hybrid Deep Learning Model. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunasingha, D.S.K. Root Mean Square Error or Mean Absolute Error? Use Their Ratio as Well. Inf. Sci. 2022, 585, 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptor | Active (Mean ± SD) | Inactive (Mean ± SD) | t-Value | p-Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW (Da) | 391.24 ± 91.17 | 371.84 ± 86.78 | 2.966 | 0.003 | ** |

| Log p | 2.53 ± 1.40 | 2.63 ± 1.40 | −0.991 | 0.322 | ns |

| HBA | 6.98 ± 1.77 | 6.69 ± 1.91 | 2.176 | 0.030 | * |

| HBD | 3.10 ± 1.72 | 2.72 ± 1.27 | 3.393 | 0.001 | *** |

| PubChem Fingerprints | Substructure Fingerprints | MACCS Fingerprints | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation Metrics | Train (774) | Test (193) | Train (796) | Test (199) | Train (769) | Test (181) |

| R-squared (R2) | 0.9934 | 0.9591 | 0.9849 | 0.9381 | 0.9924 | 0.9381 |

| MAE | 0.0593 | 0.1250 | 0.0865 | 0.1381 | 0.0642 | 0.1397 |

| MSE | 0.0070 | 0.0342 | 0.0159 | 0.0484 | 0.0085 | 0.0446 |

| RMSE | 0.0837 | 0.1848 | 0.1261 | 0.2199 | 0.0919 | 0.2111 |

| Fingerprints | Description | Fingerprints | Description | Fingerprints | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubchemFP 420 | C=O | SubFP32 | Tertiary arom amine | MACCSFP116 | Aromatic ring with a pyrazole group |

| PubchemFP 374 | C(~H)(~H)(~H) | SubFP1 | Primary carbon | MACCSFP119 | Aromatic ring with a chloro group |

| PubchemFP 372 | C(~H)(:C)(:N) | SubFP182 | Hetero O | MACCSFP78 | Aromatic ring with a chlorine group |

| PubchemFP 540 | C-N-C-[#1] | SubFP287 | Conjugated double bond | MACCSFP104 | Aromatic ring with a alkyl group |

| PubchemFP 553 | O=C-C=C | SubFP84 | Carboxylic acid | MACCSFP96 | Aromatic ring with a nitrile group |

| PubchemFP 712 | C-C(C)-C(C)-C | SubFP18 | Alkylarylether | MACCSFP90 | Aromatic ring with a nitro group |

| PubchemFP 528 | [#1]-N-C-[#1] | SubFP16 | Dialkylether | MACCSFP144 | Aromatic ring with a chloro group |

| PubchemFP 659 | O-C-C-N-C | SubFP100 | Secondary Amide | MACCSFP154 | Aromatic ring with a alkyl group |

| PubchemFP 643 | [#1]-C-C-N-[#1] | SubFP169 | Phenol | MACCSFP97 | Aromatic ring with a sulfonic acid group |

| PubchemFP 702 | O-C-C-C-C-C-N-C | SubFP2 | Secondary carbon | MACCSFP110 | Aromatic ring with an epoxide group |

| Compound | Experimental pIC50 | Predicted PubChem | Predicted Substructure | Predicted MACCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methotrexate | 9.08 | 7.65 | 7.17 | 7.37 |

| CHEMBL83644 | 8.88 | 8.32 | 7.09 | 7.38 |

| CHEMBL160699 | 8.87 | 7.14 | 7.09 | 8.26 |

| CHEMBL18925 | 7.72 | 7.36 | 7.64 | 7.50 |

| Hyperparameter | Selected Values |

|---|---|

| n_estimators max_features max_depth | 10, 50, 100, 500, 1000 auto, sqrt, log2 5, 10, 20, 30, 50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maattallaoui, I.; Sakho, M.; Maatallaoui, A.; Catalán, E.B.; Aouad, N.E. Development of QSAR Models and Web Applications for Predicting hDHFR Inhibitor Bioactivity Using Machine Learning. Molecules 2025, 30, 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234618

Maattallaoui I, Sakho M, Maatallaoui A, Catalán EB, Aouad NE. Development of QSAR Models and Web Applications for Predicting hDHFR Inhibitor Bioactivity Using Machine Learning. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234618

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaattallaoui, Ibrahim, Mahamadou Sakho, Abdellah Maatallaoui, Enrique B. Catalán, and Noureddine El Aouad. 2025. "Development of QSAR Models and Web Applications for Predicting hDHFR Inhibitor Bioactivity Using Machine Learning" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234618

APA StyleMaattallaoui, I., Sakho, M., Maatallaoui, A., Catalán, E. B., & Aouad, N. E. (2025). Development of QSAR Models and Web Applications for Predicting hDHFR Inhibitor Bioactivity Using Machine Learning. Molecules, 30(23), 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234618