Phytonutrient Profiles of Mistletoe and Their Values and Potential Applications in Ethnopharmacology and Nutraceuticals: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Distribution and Habitat of Mistletoe Families, Loranthaceae and Viscaceae

4. Ecological Impact and Value of Mistletoes

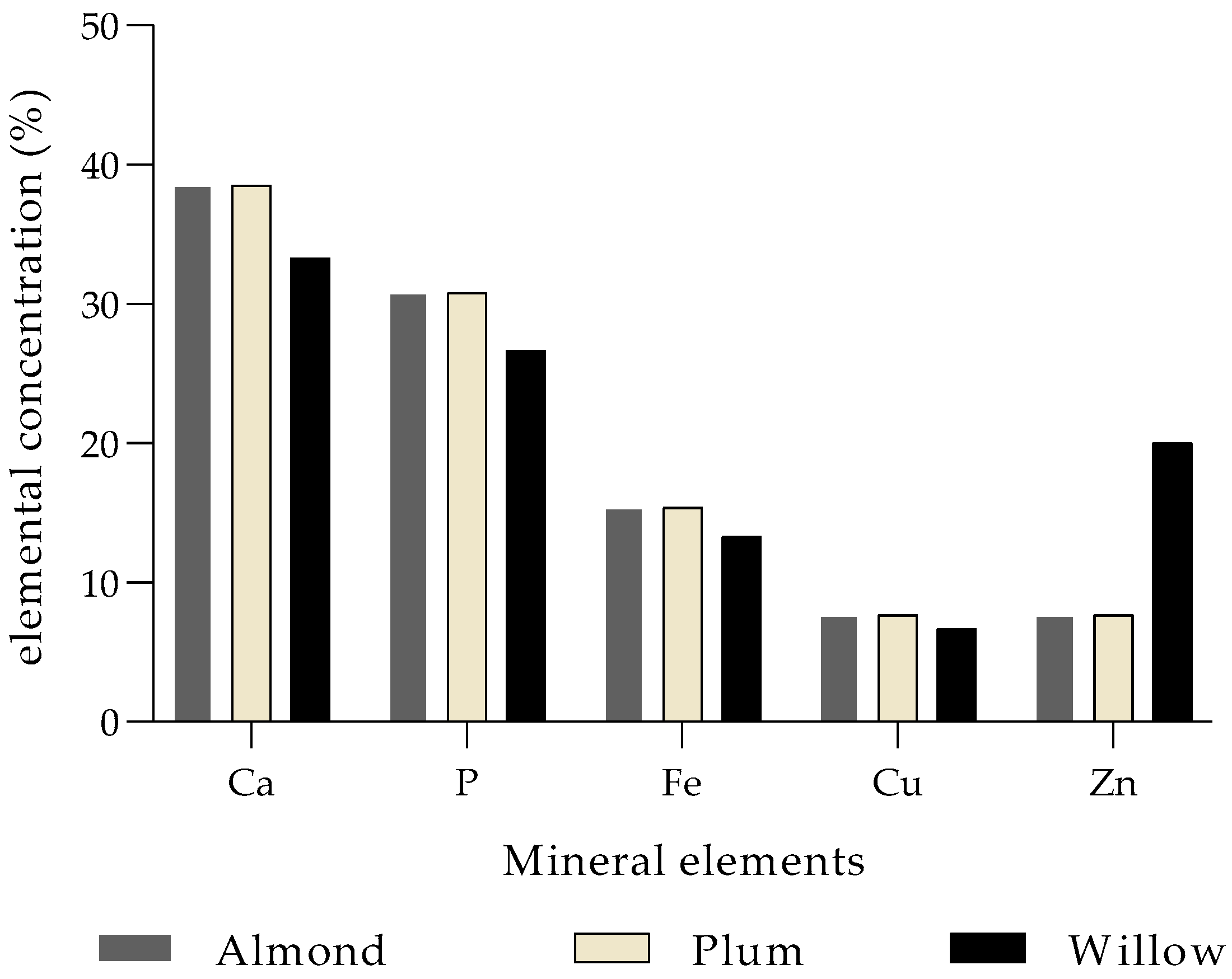

5. Nutritional Composition of Mistletoe Species

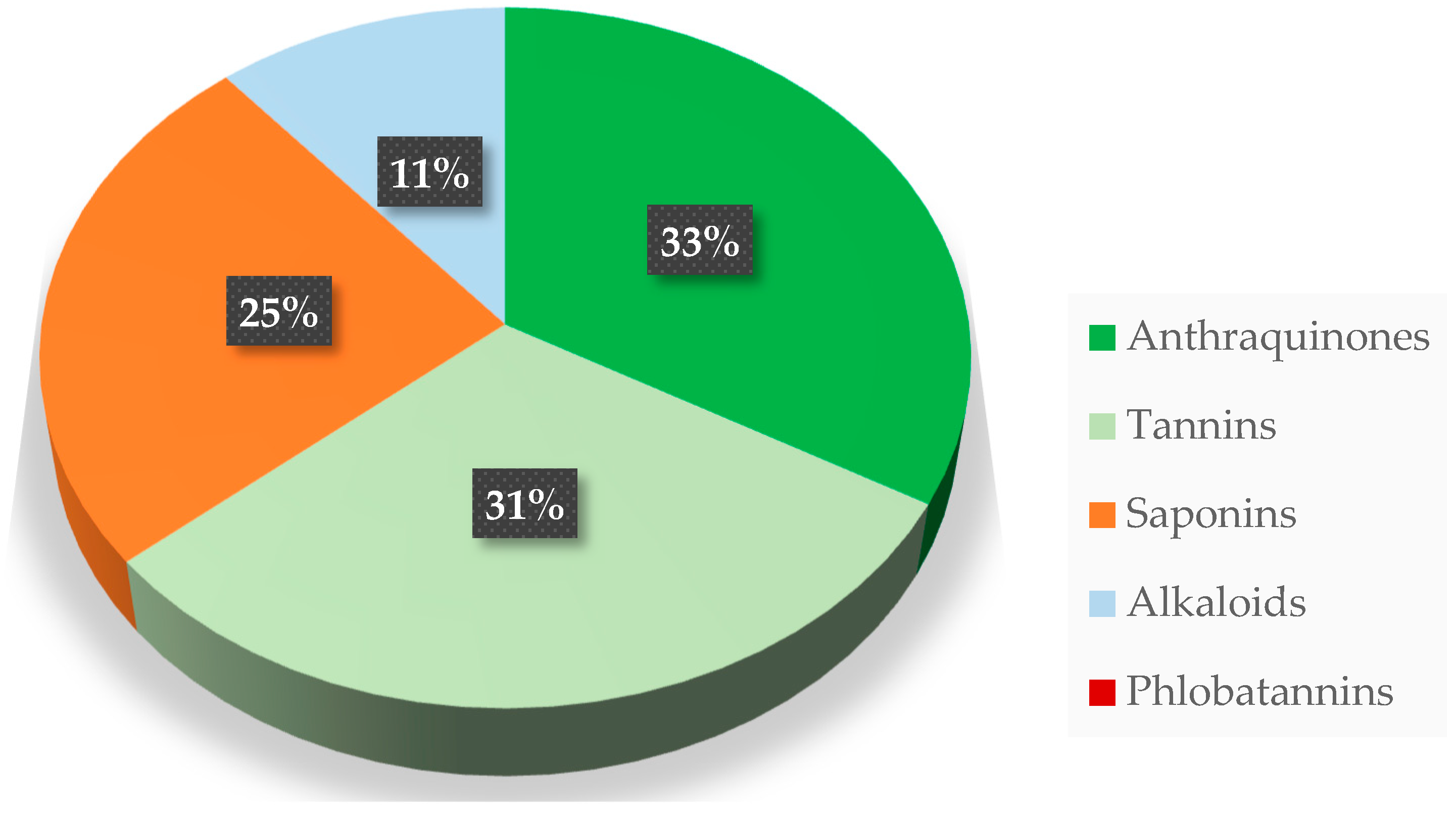

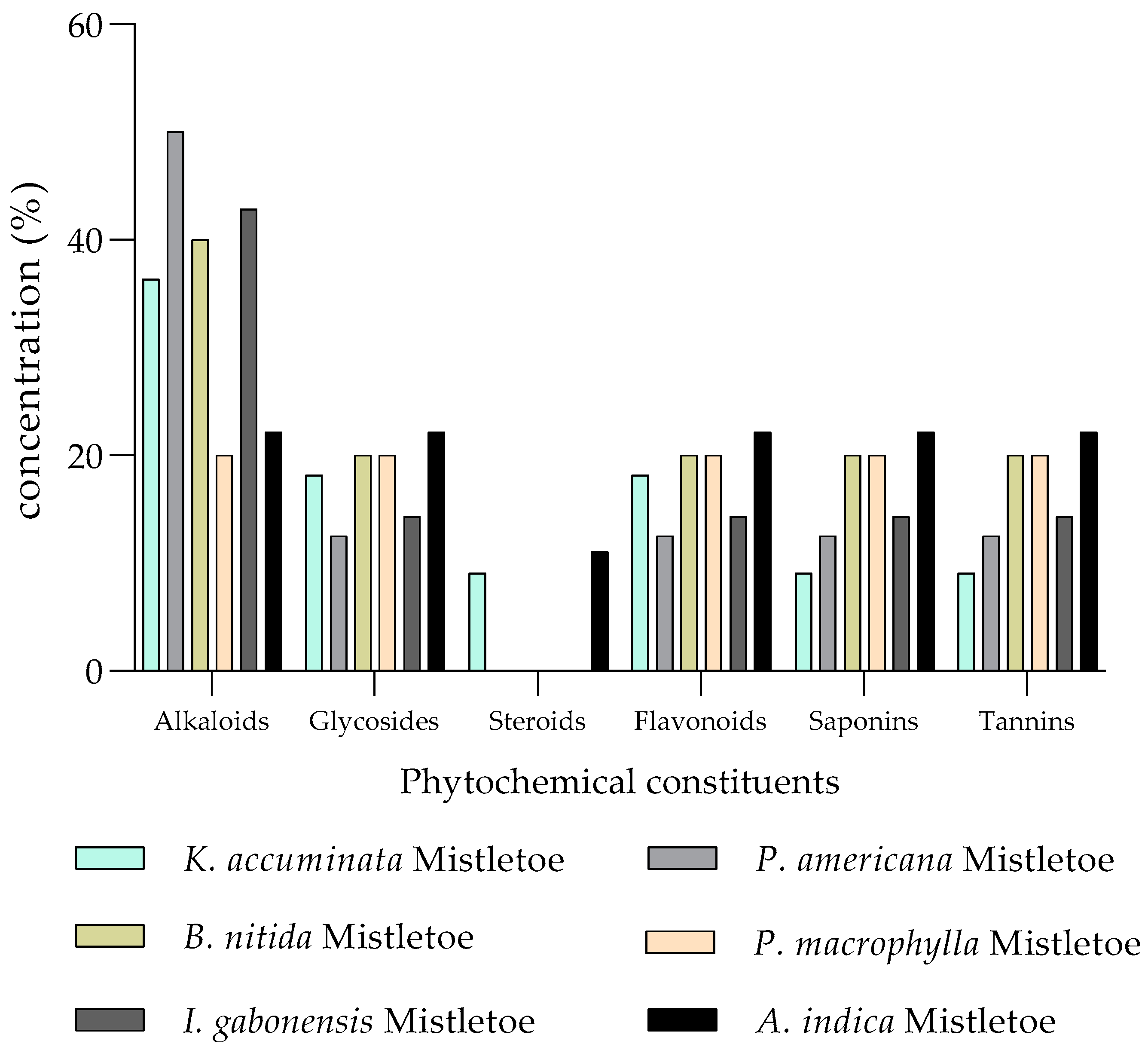

6. Phytochemical Composition of Mistletoe Species

| Mistletoe | Phytochemicals Detected | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Name | Scientific Name | ||

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus dodoneifolius (DC.) Danser | Anthraquinones, a rare presence of alkaloids, saponins, and tannins | [85] |

| Loranthaceae | Loranthus micranthus L. | Alkaloids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, glycosides and a few steroids | [89] |

| Alkaloids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids, glycosides, reducing sugars | [86] | ||

| Loranthaceae | Phragmanthera incana (Schumach.) Balle | Anthraquinones, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, cardenolides | [54] |

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus bangwensis (Engl. & K.Krause) Danser | Flavonoids, saponins, tannins, and cardiac glycosides | [14] |

| Steroidal glycoside, flavonoids, phenols, saponins, tannins | [18] | ||

| Loranthaceae | Phragmanthera capitata (Spreng.) Balle | Anthraquinones, alkaloids, phenolic acids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, cyanogenic glycosides | [15] |

| Loranthaceae | Loranthus micranthus Hook.f. | Alkaloids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, phenolic acids, steroids | [17] |

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus preussii (Engl.) Tiegh. | Anthraquinones, antioxidants, alkaloids, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, phenolic acids, steroids, cardiac glycosides, cyanogenic glycosides, carotenoids, phlobatannins | [55] |

| Loranthaceae | Scurrula atropurpurea (Blume) Danser | Polyphenols, tannins, flavonoids, monoterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids, steroids, triterpenoids and quinones | [84] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. | Alkaloids, flavonoids, viscotoxins, lectins, phenolic acids, terpenoids, sterols, phenylpropanoids | [87] |

| Terpenoids, fatty acids and vitamin E | [88] |

7. Mechanistic Basis of Host Tree Influence on Mistletoe Biochemical Composition

8. Ethnomedicinal Values and Application of Mistletoe

9. Ethnopharmacological Correlations: Bridging Traditional Use and Scientific Validation

| Mistletoe Species | Traditional Use/Ailment | Putative Active Compound(s) | Reported Biological Activity (In Vitro/In Vivo) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loranthus micranthus, Viscum album | Hypertension | Flavonoids (e.g., quercetin) and phenolic Acids | Vasorelaxant effects, ACE-inhibitory activity, antioxidant activity | [125,126] |

| Viscum album | Cancer/Tumors | Mistletoe lectins (MLs) and viscotoxins | Induction of apoptosis in cancer cells, immunomodulation (e.g., increased NK cell activity, cytokine release), direct cytotoxic/cytolytic effects | [124] |

| Viscum album, Phragmanthera spp. | Inflammation, arthritis | Flavonoids and phenolic acids | Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6), COX-2 enzyme inhibition, reduction in oxidative stress | [127] |

| Viscum album | Diabetes | Polysaccharides and flavonoids | Alpha-glucosidase and alpha-amylase inhibitory activity, improved glucose tolerance | [128] |

10. Toxicology and Safety of Mistletoe Preparations: A Critical Analysis of Evidence and Gaps

11. Commercial Status of Mistletoe Preparations and Regulatory Environment

12. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gurib-Fakim, A. Medicinal plants: Traditions of yesterday and drugs of tomorrow. Mol. Asp. Med. 2006, 27, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosthuizen, D.; Balkwill, K. Viscum songimveloensis, a new species of Mistletoe from South Africa. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 115, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatzel, G.; Geils, B.W. Mistletoe ecophysiology: Host–parasite interactions. Botany 2009, 87, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul, K.; Krug, M.; Nickrent, D.L.; Müller, K.F.; Quandt, D.; Wicke, S. Morphology, geographic distribution, and host preferences are poor predictors of phylogenetic relatedness in Mistletoe genus Viscum L. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 131, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijt, J. The Biology of Parasitic Flowering Plants; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Riopel, J.L.; Musselman, L.J. Experimental initiation of haustoria in Agalinis purpurea (Scrophulariaceae). Am. J. Bot. 1979, 66, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibberd, J.M.; Dieter Jeschke, W. Solute flux into parasitic plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 2043–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Russell, R.; Nickrent, D.L. The first Mistletoes: Origins of aerial parasitism in Santalales. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008, 47, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, J.H.; Yoder, J.I.; Timko, M.P.; Depamphilis, C.W. The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polhill, R.M.; Wiens, D. Mistletoes of Africa Royal Botanic Gardens; Kew Pages: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998; pp. 237–238. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, A. Introduction: History of Mistletoe uses. In Mistletoe; CRC Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkup, D.W.; Polhill, R.M.; Wiens, D. Viscum in the context of its family, Viscaceae, and its diversity in Africa. In Mistletoe; CRC Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tennakoon, K.U.; Chak, W.H.; Lim, L.B.; Bolin, J.F. Mineral nutrition of the hyperparasitic Mistletoe Viscum articulatum Burm.F. (Viscaceae) in tropical Brunei Darussalam. Plant Species Biol. 2014, 29, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoruyi, B.O.; Onyeneke, E.C. Proximate composition, phytochemical screening and elemental analysis of Mistletoe (Tapinanthus bangwensis) leaves. NISEB J. 2019, 11, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Isikhuemen, E.M.; Olisaemeka, U.O.; Oyibotie, G.O. Host specificity and phytochemical constituents of Mistletoe and twigs of parasitized plants: Implications for blanket application of Mistletoe as cure-all medicine. J. Med. Herbs Ethnomed. 2020, 6, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.D.; Anguiano-Cabello, J.C.; Arredondo-Valdés, R.; Candido Del Toro, C.A.; Martínez-Hernández, J.L.; Segura-Ceniceros, E.P.; Govea-Salas, M.; González-Chávez, M.L.; Ramos-González, R.; Esparza-González, S.C.; et al. Phytochemical characterization of Viscum album subs. austriacum as Mexican Mistletoe plants with antimicrobial activity. Plants 2021, 10, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloruntola, O.D.; Ayodele, S.O. Phytochemical, proximate and mineral composition, antioxidant and antidiabetic properties evaluation and comparison of Mistletoe leaves from Moringa and Kolanut trees. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 10, 1524–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwoke, S.C.; Imaga, N.O.A.; Omojufehinsi, M.; Magbagbeola, A.O.; Ebuehi, O.A.T.; Okafor, U.A. Nutritional and phytochemical properties of aqueous leaf extract of Mistletoe (Tapinanthus Bangwensis) grown on Orange tree. Univ. Lagos J. Basic Med. Sci. 2023, 10, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvibaigi, M.; Supriyanto, E.; Amini, N.; Abdul Majid, F.A.; Jaganathan, S.K. Preclinical and clinical effects of Mistletoe against breast cancer. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 785479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, D.A.; De Lange, P.J. Host specificity in parasitic Mistletoes (Loranthaceae) in New Zealand. Funct. Ecol. 1999, 13, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.M. Mistletoe, a keystone resource in forests and woodlands worldwide. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2001, 32, 219–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, B.A. Biogeography of Loranthaceae and Viscaceae. In The Biology of Mistletoes; Calder, M., Bernhardt, P., Eds.; Academic Press: Sydney, Australia, 1983; pp. 19–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sangüesa-Barreda, G.; Linares, J.C.; Camarero, J.J. Mistletoe effects on Scots pine decline following drought events: Insights from within-tree spatial patterns, growth and carbohydrates. Tree Physiol. 2012, 32, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, W.; Nowak, R. Impact of harvest conditions and host-tree species on chemical composition and antioxidant activity of extracts from Viscum album L. Molecules 2021, 26, 3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrypnik, L.; Maslennikov, P.; Feduraev, P.; Pungin, A.; Belov, N. Ecological and landscape factors affecting the spread of European Mistletoe (Viscum album L.) in urban areas (A Case Study of the Kaliningrad City, Russia). Plants 2020, 9, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, J. Viscum, Hedera and Ilex as climate indicators: A contribution to the study of the post-glacial temperature climate. Geol. Föreningen I Stockh. Förhandlingar 1944, 66, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffree, C.E.; Jeffree, E.P. Redistribution of the potential geographical ranges of Mistletoe and Colorado beetle in Europe in response to the temperature component of climate change. Funct. Ecol. 1996, 10, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, I.; Poczai, P.; Tiborcz, V.; Aranyi, N.R.; Baltazár, T.; Bartha, D.; Pejchal, M.; Hyvönen, J. Changes in the distribution of European Mistletoe (Viscum album) in Hungary during the last hundred years. Folia Geobot. 2014, 49, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skre, O. The regional distribution of vascular plants in Scandinavia with requirements for high summer temperatures. Nor. J. Bot. 1981, 26, 295–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, F.G. Crop loss assessment. In Proceedings of EC Stakman Commemorative Symposium; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1980; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, F.G. Mistletoes as Forest Parasites. In The Biology of Mistletoes; Calder, M., Bernhardt, P., Eds.; Academic Press: Sydney, Australia, 1983; pp. 317–333. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, F.G.; Wiens, D.; Geils, B.W.; Nisley, R.G. Dwarf Mistletoes: Biology, Pathology, and Systematics (No. 709); US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zorofchian Moghadamtousi, S.; Hajrezaei, M.; Abdul Kadir, H.; Zandi, K. Loranthus micranthus Linn. biological activities and phytochemistry. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 273712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, E.F.; Leaphart, C.D. Fire and dwarf Mistletoe (Arceuthobium spp.) relationships in the northern Rocky Mountains. In Proceedings of the 1974 Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference, Portland, OR, USA, 16–17 October 1976; Tall Timbers Research Station: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1976; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, K.R.; Howard, B. In Western Forest pest conditions. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Western Forestry and Conservation Association, Western Forestry and Conservation Association, Portland, OR, USA, December 1969; Volume 59, pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barbu, C. The incidence and distribution of white Mistletoe (Viscum album ssp. abietis) on Silver fir (Abies alba Mill.) stands from Eastern Carpathians. Ann. For. Res. 2010, 53, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H. European Mistletoe: Taxonomy, Host-Trees, Parts Used, Physiology, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- March, W.A.; Watson, D.M. The contribution of Mistletoes to nutrient returns: Evidence for a critical role in nutrient cycling. Austral Ecol. 2010, 35, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, S.F.; Chen, H.Y. Mechanisms regulating epiphytic plant diversity. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2012, 31, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, S.J.; Watson, D.M. An experimental approach to understanding the use of Mistletoe as a nest substrate for birds: Nest predation. Wildl. Res. 2008, 35, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bowen, M.E.; McAlpine, C.A.; House, A.P.; Smith, G.C. Agricultural landscape modification increases the abundance of an important food resource: Mistletoes, birds and brigalow. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebel, A.; Watson, D.; Pendall, E. Mistletoe, friend and foe: Synthesizing ecosystem implications of Mistletoe infection. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 115012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, W.A.; Watson, D.M. Parasites boost productivity: Effects of Mistletoe on litter fall dynamics in a temperate Australian forest. Oecologia 2007, 154, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndagurwa, H.G.; Dube, J.S.; Mlambo, D.; Mawanza, M. The influence of Mistletoes on the litter-layer arthropod abundance and diversity in a semi-arid savannah, Southwest Zimbabwe. Plant Soil 2014, 383, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, A.; Morillas, L.; Gallardo, A.; Zamora, R. Temporal dynamic of parasite-mediated linkages between the forest canopy and soil processes and the microbial community. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijt, J.; Hansen, B. Loranthaceae: Loranthaceae Juss., Ann. Mus. Hist. Nat. Paris 12: 292 (1808) (‘Loranthaea’), nom. cons.; Barlow, Flora Males. I, 13: 209–401 (1997); Polhill and Wiens, Mistletoes of Africa, Royal Bot. Gard. Kew (1998). Loranthaceae subfam. Loranthoideae Eaton, Bot. Dict., ed. 4: 37 (1836). Elytranthaceae Tiegh. (1896). Nuytsiaceae Tiegh. (1896). Gaiadendraceae Tiegh. Ex Nakai (1952). Psittacanthaceae Nakai (1952). In Flowering Plants, Eudicots: Santalales, Balanophorales; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 73–119. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.J.; Braby, M.F. Invertebrate diversity associated with tropical Mistletoe in a suburban landscape from northern Australia. North. Territ. Nat. 2009, 21, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.M.; Herring, M. Mistletoe as a keystone resource: An experimental test. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 279, 3853–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.M. Disproportionate declines in ground-foraging insectivorous birds after Mistletoe removal. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Press, M.C.; Phoenix, G.K. Impacts of parasitic plants on natural communities. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatcher, M.J.; Dick, J.T.; Dunn, A.M. Diverse effects of parasites in ecosystems: Linking interdependent processes. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoya, H.K.; Christina, O.U.; Uche, I.H. A comparative assessment of the in vitro antioxidant potential of Tapinanthus preussii (African Mistletoe) leaf aqueous and ethanolic extracts. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 6, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, S.A.; Pereira, C.; Tzortzakis, N.; Barros, L.; Ferreira, I.C. Nutritional value and bioactive compounds characterization of plant parts from Cynara cardunculus L. (Asteraceae) cultivated in central Greece. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunmefun, O.T.; Fasola, T.R.; Saba, A.B.; Oridupa, O.A. The ethnobotanical, phytochemical and mineral analyses of Phragmanthera incana (Klotzsch), a species of Mistletoe growing on three plant hosts in South-Western Nigeria. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoya, H.K.; Onyeneke, C.E.; Okwuonu, C.U.; Erifeta, G.O. Phytochemical, proximate and elemental analysis of the African Mistletoe (Tapinanthus preussii) crude aqueous and ethanolic leaf extracts. Extraction 1993, 21, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Chizoruo, I.F.; Onyekachi, I.B.; Odinaka, N.P.; Chinyelu, E.M. Phytochemical, FTIR and elemental studies of African Mistlotoe (Viscum album) leaves on Cola nitida from South-Eastern Nigeria. World Sci. News 2019, 132, 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Barberaki, M.; Kintzios, S. Accumulation of selected macronutrients in Mistletoe tissue cultures: Effect of medium composition and explant source. Sci. Hortic. 2002, 95, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türe, C.; Böcük, H.; Aşan, Z. Nutritional relationships between hemiparasitic Mistletoe and some of its deciduous hosts in different habitats. Biologia 2010, 65, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, P.; Strong, G.L.; Andrew, I. Differential accumulation of nutrient elements in some New Zealand Mistletoes and their hosts. Funct. Plant Biol. 2002, 29, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, E.D.; Lange, O.L.; Ziegler, H.; Gebauer, G. Carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios of Mistletoes growing on nitrogen and non-nitrogen fixing hosts and on CAM plants in the Namib Desert confirm partial heterotrophy. Oecologia 1991, 88, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makinta, A.A.; Igwebuike, J.U.; Kwari, I.D.; Mohammed, G. Determination of proximate composition, some anti-nutritional factors and amino acid profile of Mistletoe leaf (Tapinanthus bangwensis) meal. Niger. J. Anim. Prod. 2023, 6, 909–913. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.W.; An, C.H.; Lee, H.S.; Yi, J.S.; Cheong, E.J.; Lim, S.H.; Kim, H.Y. Proximate and mineral components of Viscum album var. coloratum grown on eight different host-tree species. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnisi, C.M.; Ramantsi, R.; Ravhuhali, K. Chemical composition and in vitro dry matter degradability of Mistletoe (Viscum verrucosum (Harv.)) on Vachellia nilotica (L.) in North West Province of South Africa. Trop. Agric. 2019, 96, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Umudi, E.Q.; Umudi, O.P.; Diakparomre, O.; Obiagwe, J.; Nwakwanogo, B.E. Analysis of the Mineral Nutritional and Phytochemical Composition of Mistletoe Leaves (Loranthaceae). Fac. Nat. Appl. Sci. J. Appl. Chem. Sci. Res. 2024, 2, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ciftci, B.; Karaman, S.; Kamalak, A.; Kaplan, M. Effects of Hosting Trees on Chemical Composition, Minerals, Amino Acid, Fatty Acid Composition and Gas-Methane Production of Mistletoe (Viscum album) Leaves. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 12, 6803–6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Gullo, M.A.; Glatzel, G.; Devkota, M.; Raimondo, F.; Trifilò, P.; Richter, H. Mistletoes and mutant albino shoots on woody plants as mineral nutrient traps. Ann. Bot. 2012, 109, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubamichael, D.Y.; Griffiths, M.E.; Ward, D. Host specificity, nutrient and water dynamics of Mistletoe Viscum rotundifolium and its potential host species in the Kalahari of South Africa. J. Arid. Environ. 2011, 75, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowie, M.; Ward, D. Water and nutrient status of Mistletoe Plicosepalus acaciae parasitic on isolated Negev Desert populations of Acacia raddiana differing in level of mortality. J. Arid. Environ. 2004, 56, 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubamichael, D.Y. Host Specificity of the Hemiparasitic Mistletoe, Agelanthus natalitius. Ph.D. Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Panvini, A.D.; Eickmeier, W.G. Nutrient and water relations of Mistletoe Phoradendron leucarpum (Viscaceae): How tightly are they integrated? Am. J. Bot. 1993, 80, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umucalilar, H.D.; Gülşen, N.; Coşkun, B.E.H.İ.Ç.; Hayirli, A.; Dural, H.Ü.S.E.Y.İ.N. Nutrient composition of Mistletoe (Viscum album) and its nutritive value for ruminant animals. Agrofor. Syst. 2007, 71, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassey, P.; Sowemimo, A.; Lasore, O.; Spies, L.; van de Venter, M. Biological activities and nutritional value of Tapinanthus bangwensis leaves. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 11, 13821–13826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.J.; Jiang, D.H.; Yang, Z.; Guo, X.N.; Zhu, K.X. effect of humidity-controlled dehydration on microbial growth and quality characteristics of fresh wet noodles. Foods 2021, 10, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohikhena, F.U.; Wintola, O.A.; Afolayan, A.J. Proximate composition and mineral analysis of Phragmanthera capitata (Sprengel) Balle, a Mistletoe growing on rubber tree. Res. J. Bot. 2017, 12, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.P.; Goswami, A.; Kalia, K.; Kate, A.S. Plant-Derived Bioactive Peptides: A Treatment to Cure Diabetes. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2020, 26, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwu, C.N.; Obiegbuna, J.E.; Aniagolu, N.M. Evaluation of chemical properties of Mistletoe leaves from three different trees (Avocado, African Oil Bean and Kola). Niger. Food J. 2013, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarfa, F.D.; Amos, S.; Temple, V.J.; Binda, L.; Emeje, M.; Obodozie, O.; Wambebe, C.; Gamaniel, K. Effect of the aqueous extract of African Mistletoe, Tapinanthus sessilifolius (P. Beauv) van Tiegh leaf on gastrointestinal muscle activity. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2002, 40, 571–574. [Google Scholar]

- Madibela, O.R.; Boitumelo, W.S.; Letso, M. Chemical composition and in vitro dry matter digestibility of four parasitic plants (Tapinanthus lugardii, Erianthenum ngamicum, Viscum rotundifolium and Viscum verrucosum) in Botswana. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2000, 84, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinmoladun, A.C.; Ibukun, E.O.; Afor, E.; Obuotor, E.M.; Farombi, E.O. Phytochemical constituent and antioxidant activity of extract from the leaves of Ocimum gratissimum. Sci. Res. Essay 2007, 2, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Jan, R.; Lubna, A.S.; Khan, M.A.; Kim, K.M. Effect of Mineral Nutrition and PGRs on Biosynthesis and Distribution of Secondary Plant Metabolites under Abiotic Stress. In Medicinal Plants: Their Response to Abiotic Stress; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 287–314. [Google Scholar]

- Senthilkumaran, S.; Meenakshisundaram, R.; Thirumalaikolundusubramanian, P. Plant toxins and the heart. In Heart and Toxins; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, A.F. Economic botany. A textbook of useful plants and plant products. In Economic Botany, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Publishing Co., Ltd.: London, UK, 1937; pp. x + 592. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Cordero, C.; Gil Serrano, A.M.; Ayuso Gonzalez, M.J. Transfer of bipiperidyl and quinolizidinevalkaloids to Viscum cruciatum Sieber (Loranthaceae) hemiparasitic on Retama sphaerocarpa Boissier (Leguminosae). J. Chem. Ecol. 1993, 19, 2389–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, K.; Winarno, H.; Mukai, M.; Inoue, M.; Prana, M.S.; Simanjuntak, P.; Shibuya, H. Indonesian medicinal plants. XXV. Cancer cell invasion inhibitory effects of chemical constituents in the parasitic plant Scurrula atropurpurea (Loranthaceae). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 51, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeni, Y.Y.; Sadiq, N.M. Antimicrobial properties and phytochemical constituents of the leaves of African Mistletoe (Tapinanthus dodoneifolius (DC) Danser (Loranthaceae): An ethnomedicinal plant of Hausaland, Northern Nigeria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ukwueze, S.E.; Osadebe, P.O.; Ezenobi, N.O. Bioassay-guided evaluation of the antibacterial activity of Loranthus species of the African Mistletoe. Int. J. Pharm. Biomed. Res. 2013, 4, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Szurpnicka, A.; Zjawiony, J.K.; Szterk, A. Therapeutic potential of Mistletoe in CNS-related neurological disorders and the chemical composition of Viscum species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 231, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, D.C.; Popescu, R.; Dumitrascu, V.; Cimporescu, A.; Vlad, C.S.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Krisch, J.; Dehelean, C.; Horhat, F.G. Phyto-components identification in Mistletoe (Viscum album) young leaves and branches, by GC-MS and antiproliferative effect on HEPG2 and McF7 cell lines. Farm. J. 2016, 64, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Osadebe, P.O.; Ukwueze, S.E. A comparative study of the phytochemical and anti-microbial properties of the Eastern Nigerian specie of African Mistletoe (Loranthus micranthus) sourced from different host-trees. Bioresearch 2004, 2, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schötterl, S.; Miemietz, J.T.; Ilina, E.I.; Wirsik, N.M.; Ehrlich, I.; Gall, A.; Huber, S.M.; Lentzen, H.; Mittelbronn, M.; Naumann, U. Mistletoe-based drugs work in synergy with radio-chemotherapy in the treatment of glioma in vitro and in vivo in glioblastoma bearing Mice. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 1376140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Barberán, M.; Lerma-García, M.J.; Nicoletti, M.; Simó-Alfonso, E.F.; Herrero-Martínez, J.M.; Fasoli, E.; Righetti, P.G. Proteomic fingerprinting of Mistletoe (Viscum album L.) via combinatorial peptide ligand libraries and mass spectrometry analysis. J. Proteom. 2017, 164, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñaloza, E.; Holandino, C.; Scherr, C.; Araujo, P.I.; Borges, R.M.; Urech, K.; Baumgartner, S.; Garrett, R. Comprehensive metabolome analysis of fermented aqueous extracts of Viscum album L. by liquid chromatography−high resolution tandem mass spectrometry. Molecules 2020, 25, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaurinovic, B.; Vastag, D. Flavonoids and phenolic acids as potential natural antioxidants. Antioxidants 2019, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Luczkiewicz, M.; Cisowski, W.; Kaiser, P.; Ochocka, R.; Piotrowski, A. Comparative analysis of phenolic acids in Mistletoe plants from various hosts. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2001, 58, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haas, K.; Bauer, M.; Wollenweber, E. Cuticular waxes and flavonol aglycones of Mistletoes. Z. Naturforsch. C J. Biosci. 2003, 58, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, W.; Nowak, R.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Lemieszek, M.; Rzeski, W. LC-ESI-MS/MS identification of biologically active phenolic compounds in Mistletoe berry extracts from different host-trees. Molecules 2017, 22, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.Z.; Zhao, J.T.; Wang, W.Q.; Fan, R.H.; Rong, R.; Yu, Z.G.; Zhao, Y.L. Metabolomics-based comparative analysis of the effects of host and environment on Viscum coloratum metabolites and antioxidative activities. J. Pharm. Anal. 2021, 12, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 98Obatomi, D.K.; Bikomo, E.O.; Temple, V.J. Anti-diabetic properties of the African Mistletoe in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1994, 43, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rout, G.R.; Samantaray, S.; Das, P. In vitro manipulation and propagation of medicinal plants. Biotechnol. Adv. 2000, 18, 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.P.; Ganju, L.; Sairam, M.; Banerjee, P.K.; Sawhney, R.C. A review of high throughput technology for the screening of natural products. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2008, 62, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, P. Concerns regarding the safety and toxicity of medicinal plants-An overview. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 1, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ojewole, J.; Kamadyaapa, D.R.; Gondwe, M.M.; Moodley, K.; Musabayane, C.T. Cardiovascular effects of Persea americana Mill (Lauraceae) (Avocado) aqueous leaf extract in experimental animals. Cardiovasc. J. S. Afr. 2007, 18, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Ohikhena, F.U.; Wintola, O.A.; Afolayan, A.J. Quantitative phytochemical constituents and antioxidant activities of Mistletoe, Phragmanthera capitata (sprengel) Balle extracted with different solvents. Pharmacogn. Res. 2018, 10, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Mahady, G.B. Global harmonization of herbal health claims. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1120–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafaru, E. ‘Mistletoe, an example of an all-purpose herb’ Herbal Remedies. The Guardian Newspaper, London, UK, 3 June 1993; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Nwude, N.; Ibrahim, M.A. Plants used in traditional veterinary medical practice in Nigeria. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 1980, 3, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, E.; Link, S.; Toffol-Schmidt, U. Cytostatic and cytocidal effects of Mistletoe (Viscum album L.) aqueous extract Iscador. Arzneimittelforschung 2006, 56, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Gabius, H.J.; Gabius, S.; Joshi, S.S.; Koch, B.; Schroeder, M.; Manzke, W.M.; Westerhausen, M. From ill-defined extracts to the immunomodulatory lectin: Will there be a reason for oncological application of Mistletoe? Planta Medica 1994, 60, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.B.; Lyu, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.H.; Chung, H.K.; Ahn, S.H.; Hong, S.Y.; Yoon, T.J.; Choi, M.J. Inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis by Korean Mistletoe lectins is associated with apoptosis and antiangiogenesis. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2001, 16, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urech, K.; Schaller, G.; Jäggy, C. Viscotoxins, Mistletoe lectins and their isoforms in Mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extracts Iscador. Arzneimittelforschung 2006, 56, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzerling, L.; Von Baehr, V.; Liebenthal, C.; Von Baehr, R.; Volk, H.D. Immunologic effector mechanisms of a standardized Mistletoe extract on the function of human monocytes and lymphocytes in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo. J. Clin. Immunol. 2006, 26, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elluru, S.; Huyen, J.V.; Bharath Wootla, B.W.; Delignat, S.; Prost, F.; Negi, V.S.; Kaveri, S.V. Tumor regressive effects of Viscum album preparations. In Proceedings of the Exploration of Immunomodulatory Mechanisms, International Symposium, New Directions in Cancer Management, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 6–8 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, A. Immune modulation using Mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extracts Iscador. Arzneimittelforschung 2006, 56, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schink, M.; Tröger, W.; Dabidian, A.; Goyert, A.; Scheuerecker, H.; Meyer, J.; Fischer, I.U.; Glaser, F. Mistletoe extract reduces the surgical suppression of natural killer cell activity in cancer patients. A randomized phase III trial. Res. Complement. Med. 2007, 14, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engdal, S.; Nilsen, O.G. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein in Caco-2 cells: Effects of herbal remedies frequently used by cancer patients. Xenobiotica 2008, 38, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Bian, H.J.; Bao, J.K. Plant lectins: Potential antineoplastic drugs from bench to clinic. Cancer Lett. 2010, 287, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofowora, L.A. Medicinal Plants and Traditional Medicine in Africa; Spectrum Books Ltd.: Ibadan, Nigeria, 1993; pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, N.D. Antioxidant flavonoids: Structure, function and clinical usage. Altern. Med. Rev. 1996, 1, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Büssing, A.; Schietzel, M. Apoptosis-inducing properties of Viscum album L. extracts from different host-trees correlate with their content of toxic Mistletoe lectins. Anticancer Res. 1999, 19, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khammash, A. “Holly Parasite or Christmas Mistletoe” Jordan Times Weekender. 2005. Available online: http://www.jordanflora.com/holly.htm (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Atewolara-Odule, O.C.; Aiyelaagbe, O.O.; Ashidi, J.S. Biological and phytochemical investigation of extracts of Tapinanthus bangwensis (Engl. and K. Krause) Danser (Loranthaceae) grown in Nigeria. Afr. J. Sci. Nat. 2018, 6, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanavaskhan, A.E.; Sivadasan, M.; Alfarhan, A.H.; Thomas, J. Ethnomedicinal aspects of angiospermic epiphytes and parasites of Kerala, India. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2012, 11, 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Q.K. Loranthus ferrugineus: A Mistletoe from traditional uses to laboratory bench. J. Pharmacopunct. 2015, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienle, G.S.; Kiene, H. Influence of Viscum album L. (European mistletoe) extracts on quality of life in cancer patients: A systematic review of controlled clinical studies. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2010, 9, 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaller, G.; Urech, K.; Giannattasio, M. Cytotoxicity of different viscotoxins and extracts from the European subspecies of Viscum album L. Phytother. Res. 1996, 10, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Inzunza, L.A.; Heredia, J.B.; Patra, J.K.; Gouda, S.; Kerry, R.G.; Das, G.; Gutierrez-Grijalva, E.P. Traditional uses, phytochemical constituents and ethnopharmacological properties of mistletoe from Phoradendron and Viscum species. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2024, 27, 1093–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletti, M. The anti-inflammatory activity of Viscum album. Plants 2023, 12, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.M.; Flatt, P.R. Insulin-secreting activity of the traditional antidiabetic plant Viscum album (mistletoe). J. Endocrinol. 1999, 160, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briskin, D.P. Medicinal plants and phytomedicines. Linking plant biochemistry and physiology to human health. Plant Physiol. 2000, 124, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horneber, M.; van Ackeren, G.; Linde, K.; Rostock, M. Mistletoe therapy in oncology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 2008, CD003297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wely, M.; Stoss, M.; Gorter, R.W. Toxicity of a standardized Mistletoe extract in immunocompromised and healthy individuals. Am. J. Ther. 1999, 6, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.; Lüdtke, R.; Klassen, M.; Müller-Buscher, G.; Wolff-Vorbeck, G.; Scheer, R. Effects of a Mistletoe preparation with defined lectin content on chronic hepatitis C: An individually controlled cohort study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2001, 6, 399–405. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, R.; Klein, R.; Berg, P.A.; Lüdtke, R.; Werner, M. Effects of a lectin- and a viscotoxins-rich Mistletoe preparation on clinical and hematological parameters: A placebo-controlled evaluation in healthy subjects. J. Altern. Compl. Med. 2002, 8, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G.M.; Berg, P.A. Characterisation of immunological reactivity of patients with adverse effects during therapy with an aqueous Mistletoe extract. Eur. J. Med. Res. 1999, 4, 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, R.; Eisenbraun, J.; Miletzki, B.; Adler, M.; Scheer, R.; Klein, R.; Gleiter, C.H. Pharmacokinetics of natural Mistletoe lectins after subcutaneous injection. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 66, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, L.; Aamdal, S.; Marreaud, S.; Lacombe, D.; Herold, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Wilhelm-Ogunbiyi, K.; Lentzen, H.; Zwierzina, H. Phase I trial of r viscumin (INN: Aviscumine) given subcutaneously in patients with advanced cancer: A study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC protocol number 13001). Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 44, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.; Rostock, M.; Goedl, R.; Ludtke, R.; Urech, K.; Buck, S.; Klein, R. Mistletoe treatment induces GM-CSF-and IL-5 production by PBMC and increases blood granulocyte-and eosinophil counts: A placebo controlled randomized study in healthy subjects. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2005, 10, 411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huber, R.; Lüdtke, H.; Wieber, J.; Beckmann, C. Safety and effects of two Mistletoe preparations on production of Interleukin-6 and other immune parameters-a placebo controlled clinical trial in healthy subjects. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldacker, J. Preclinical investigations with Mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extract Iscador. Arzneimittelforschung 2006, 56, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Community Code Relating to Medicinal Products for Human Use; European Medicines Agency (EMA): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Freuding, M.; Keinki, C.; Micke, O.; Buentzel, J.; Huebner, J. Mistletoe in oncological treatment: A systematic review: Part 1: Survival and safety. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mistletoe Species | Elements | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Scientific Name | ||

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus preussii (Engl.) Tiegh. | Ca, Fe, K, Na, Mg, Zn, PO43− | [55] |

| Loranthaceae | Tupeia antarctica (G.Forst.) Cham. & Schltdl. | Ca, Mg, K, Na, P, N | [56] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. | Ca, Mg, K, P | [57] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. subsp. album | Ca, Mg, Fe, Mn, N, P, K, Na, S, Cu, Zn, B | [58] |

| Ca, N, P, K, Na, S, Mg, Fe, Cu, Zn, Mn, Mo, B | [59] | ||

| Loranthaceae | Ileostylus micranthus (Hook.f.) Tiegh. | Ca, Mg, K, Na, P, N | [60] |

| Loranthaceae | Loranthus micranthus Hook.f. | Ca, Mg, P, Zn | [17] |

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus bangwensis (Engl. & K.Krause) Danser | Ca, Mg, Mn, P, Zn, K, I, Fe, Na | [18] |

| Loranthaceae | Phragmanthera incana (Schumach.) Balle | Ca, Mg, K, Na | [54] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album subsp. austriacum (Wiesb.) Vollm. | Ca, Mg, P, K, Mn, Cu, Zn, Fe, Se, S, Cl | [16] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum articulatum Burm. f. | Ca, Mg, Mn, Cu, K, P, Fe, Zn, N | [13] |

| Family Name | Botanical Name | Nutritional Constituents and Est. Value (g/100 g Dry Weight) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loranthaceae | Loranthus micranthus Hook.f. | Moisture (18), crude fiber (10.5), crude protein (11.2), nitrogen-free extract (69.5), fat (3.8) and ash content (4.5) | [17] |

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus bangwen- sis (Engl. & K. Krause) Danser | Crude fat (4.2), protein (12.5), total carbohydrates (68.4), crude fiber (9.8), moisture content (7.5) and ash (5.1) | [18] |

| Moisture (8.2), ash (4.8), crude protein (14.1), ether extract (3.5), crude fiber (11.2) and nitrogen-free extract (NFE) (66.4) | [61] | ||

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus preussii (Engl.) Tiegh. | Moisture (7.8), ether extract (fat) (4.5), ash (5.5), protein (13.8), crude fiber (10.8) and carbohydrates (65.4) | [52] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album var. coloratum | Carbohydrates (58.4), crude protein (16.8), crude fiber (14.2), crude ash (5.8) and crude fat (4.8) | [62] |

| Viscaceae | Ziscum verrucosum (Harv.) | Dry matter 927.3, organic matter 821.6, crude protein (123.4), neutral detergent fiber, acid detergent fiber and acid detergent lignin | [63] |

| Loranthaceae | Phragmanthera incana (Schumach.) Balle | Fat (5.1), moisture (6.9), crude fiber (12.4), crude protein (15.3), ash (6.2) and carbohydrates (61.0) | [64] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. | Crude protein (12.33), crude oil (5.49), crude ash (7.39), neutral detergent fiber (31.37), and acid detergent fiber (25.73) | [65] |

| Elements | Host Tree Species | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. alba | S. alba | R. pseudoacacia | C. monogyna | |

| N | +↓ | +↓ | ++↑ | +↓ |

| Ca | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ | +↓ |

| P | +↓ | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ |

| K | +↓ | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ |

| Na | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ | +↓ |

| Mg | +↓ | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ |

| Mn | +↓ | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ |

| Fe | +↓ | +↓ | +↓ | ++↑ |

| Zn | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ | +↓ |

| Cu | +↓ | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ |

| S | +↓ | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ |

| Mo | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ | |

| B | +↓ | ++↑ | +↓ | +↓ |

| Family Name | Scientific Name | Phenolic Acids | Flavonoids | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. ssp album | Gallic acid (12.5 mg/g), caffeic acid (3.2 mg/g), ferulic acid (1.1 mg/g), p-Coumaric acid (0.8 mg/g), salicylic acid, gentisic acid, grotocatechuic acid, p-hydrobenzoic, rosmarinic acid, and sinapic acid (other acids detected in trace amounts) | 3-O-Methyl quercetin (8.7 mg/g), apigenin (2.1 mg/g), and naringenin (0.5 mg/g) | [94] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. ssp abietis | p-Coumaric acid (9.8 mg/g), ferulic acid (4.5 mg/g), caffeic acid (2.1 mg/g), salicylic acid, protocatechuic acid, 4-hydrobenzoic acid, vanilic acid, and sinapic acid (other acids detected in trace amounts) | Rhamnetin (5.5 mg/g), 3-O-Methyl quercetin (3.2 mg/g), naringenin (1.1 mg/g), rhamnazin, and apigenin (other acids detected in trace amounts) | [95] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. ssp austriacum | Sinapic acid (15.2 mg/g), ferulic acid (6.7 mg/g), caffeic acid (3.4 mg/g), protocatechuic acid, salicylic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanilic acid, and p-Coumaric acid (other acids detected in trace amounts) | Quercetin (10.1 mg/g), myricetin (9.5 mg/g), kaempferol (4.3 mg/g), naringenin, eriodictyol, sakuranetin, isorhamnetin, rhamnazin, and rhamnetin (other acids detected in trace amounts) | [96] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. ssp coloratum | Not detected (ND) | Eriodictyol (0.8 mg/g) | [97] |

| Mistletoe Species | Medicinal Values and Application | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Name | Scientific Name | ||

| Loranthaceae | Loranthus bengwensis L. | To treat Diabetes mellitus | [98] |

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus dodoneifolius (DC.) Danser | Antimicrobial activities against certain multiple drug-resistant bacteria and fungal isolates | [81] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. var album | Diabetes, high blood pressure and insomnia | [54] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. | To treat skin diseases and prostate cancer, anticancer, antihypertensive activity and antidiabetic properties | [120] |

| Loranthaceae | Tapinanthus bangwensis (Engl. & K.Krause) Danser | Antihypertensive and antidiabetic agents | [121] |

| Hypotensive, hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effect, which lowers blood pressure, blood glucose and lipid profile | [14] | ||

| Viscaceae | Viscum articulatum Burm. f. | Paste and decoction are given to cure cuts, wounds, bone fractures, ulcers and blood diseases, epilepsy and sprains | [122] |

| Loranthaceae | Loranthus ferrugineus Roxb. ex. Jack | Hypertension and gastrointestinal complaint management | [123] |

| Viscaceae | Viscum album L. var. coloratum Ohwi | Material for anticancer functional foods for treatment of tumorigenic cells | [109] |

| Preparation | Extract | Host Tree | Application | Dosage (mg Extract or ng ML) | Standardization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phytotherapeutic preparations | |||||

| Eurixor® | Aqueous (herb) | Poplar | Subcutaneous, intracutaneous, intravenous | 1 mg or 70 ng/ampule (1 mL) | ML-I |

| Lektinol® | Aqueous (herb) | Poplar | Subcutaneous | 0.02–0.07 mg or 15 ng/ampule n(0.5 mL) | ML-I |

| Anthroposophic preparations | |||||

| Helixor® | Aqueous (herb) | Apple, fir and pine tree | Subcutaneous | 0.01–50 mg/amp. (1 mL), 100 mg (2 mL) | Process |

| Iscador® | Aqueous lacto-fermented (herb) | Elm and oak tree | Subcutaneous | 0.0001–20 mg/ampule (1 mL) | Process |

| Isorel® | aqueous (planta tota) | M, P, A | Subcutaneous, intramuscular | 1–60 mg | Process |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mopai, M.G.; Mpai, S.; Van Staden, J.; Ndhlala, A.R. Phytonutrient Profiles of Mistletoe and Their Values and Potential Applications in Ethnopharmacology and Nutraceuticals: A Review. Molecules 2025, 30, 4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224390

Mopai MG, Mpai S, Van Staden J, Ndhlala AR. Phytonutrient Profiles of Mistletoe and Their Values and Potential Applications in Ethnopharmacology and Nutraceuticals: A Review. Molecules. 2025; 30(22):4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224390

Chicago/Turabian StyleMopai, Maeleletse G., Semakaleng Mpai, Johannes Van Staden, and Ashwell R. Ndhlala. 2025. "Phytonutrient Profiles of Mistletoe and Their Values and Potential Applications in Ethnopharmacology and Nutraceuticals: A Review" Molecules 30, no. 22: 4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224390

APA StyleMopai, M. G., Mpai, S., Van Staden, J., & Ndhlala, A. R. (2025). Phytonutrient Profiles of Mistletoe and Their Values and Potential Applications in Ethnopharmacology and Nutraceuticals: A Review. Molecules, 30(22), 4390. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30224390