The Role of the NO/cGMP Pathway and SKCa and IKCa Channels in the Vasodilatory Effect of Apigenin 7-Glucoside

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

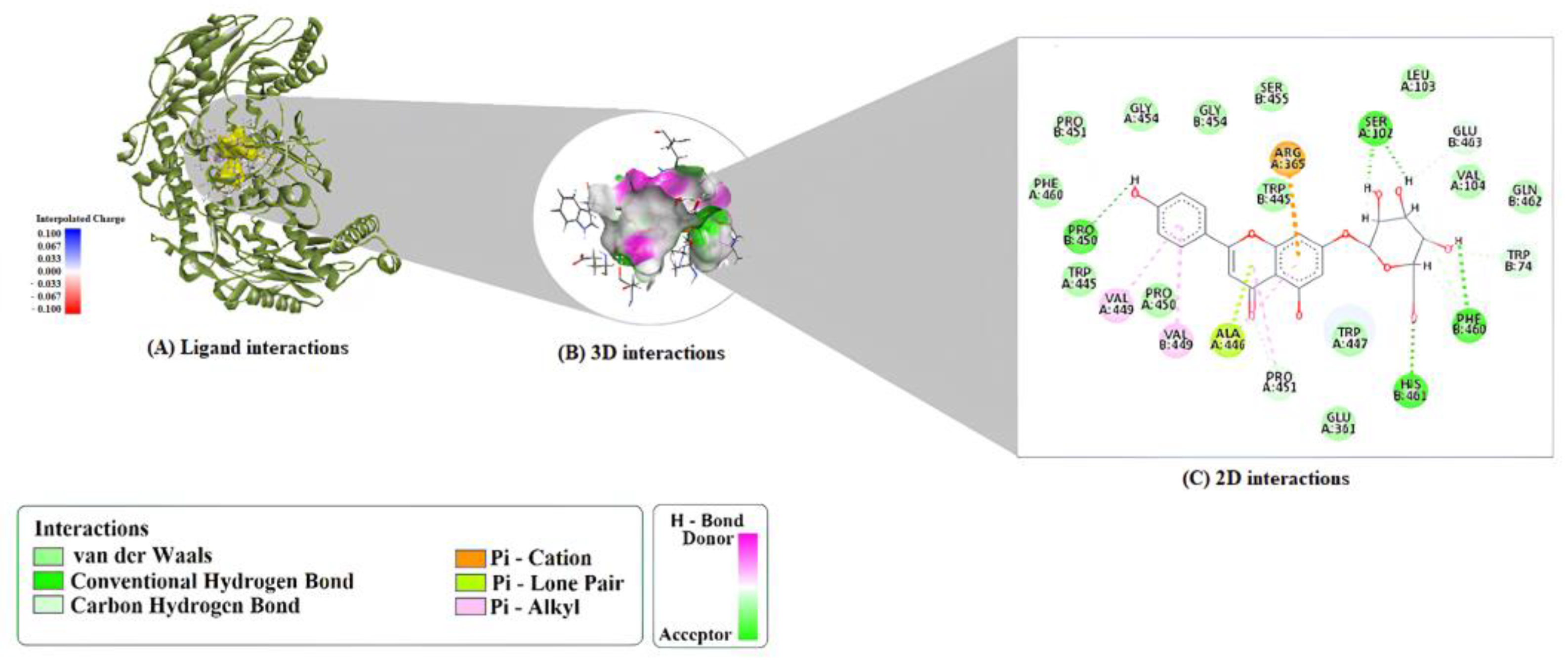

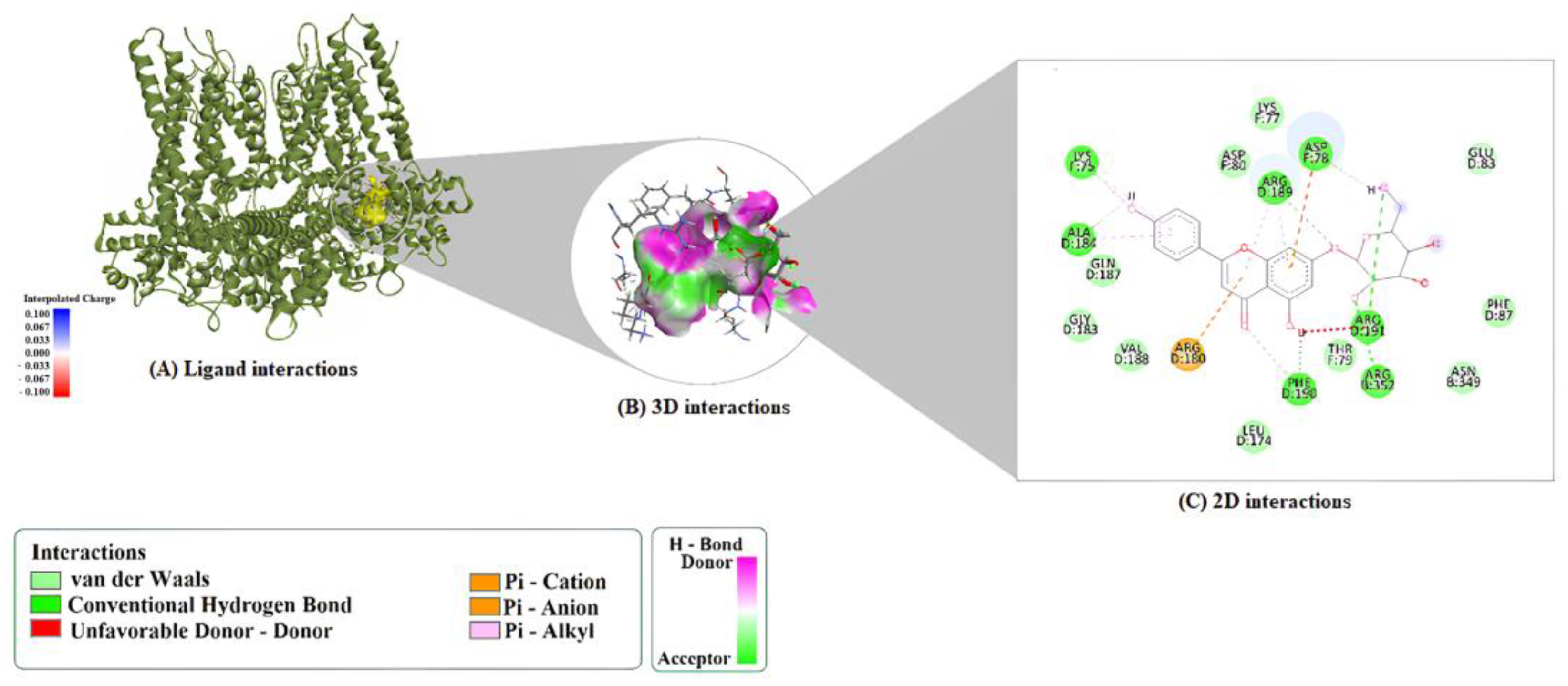

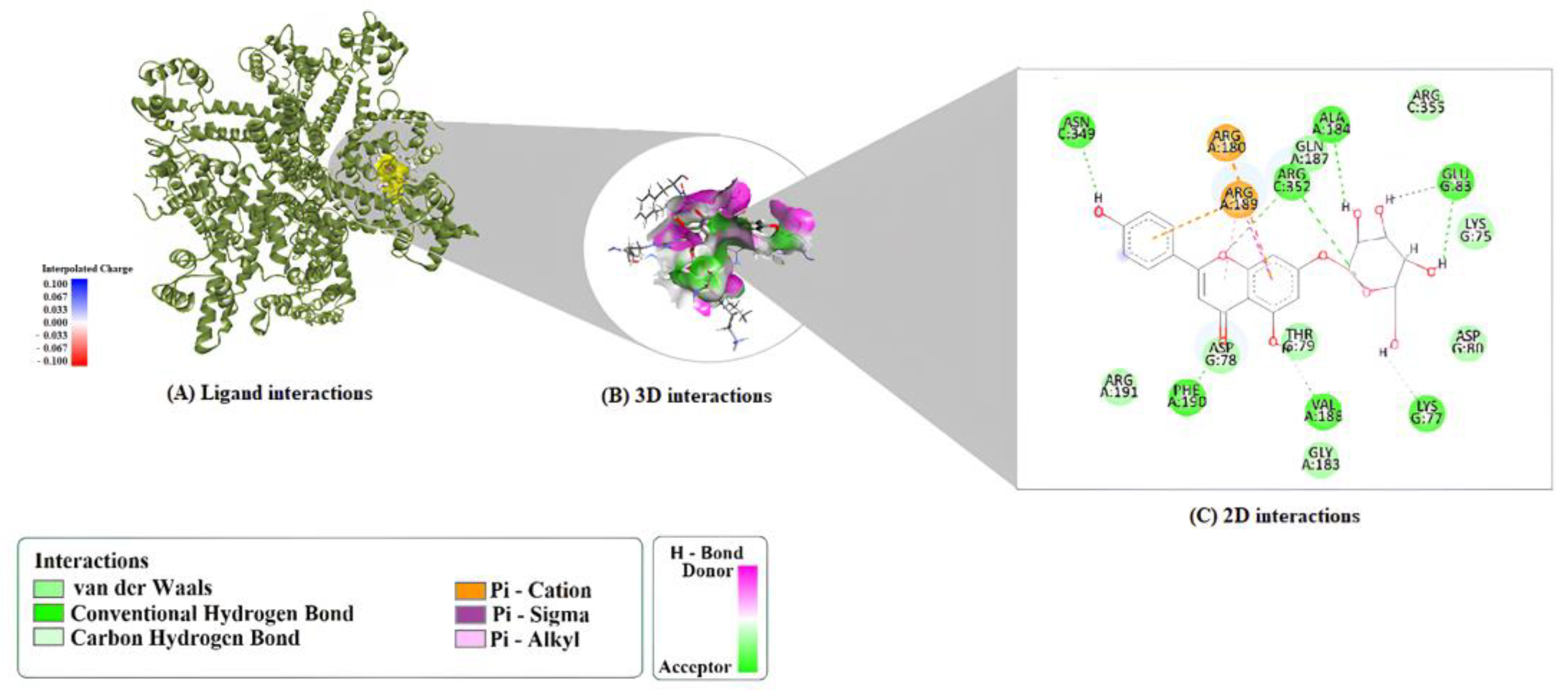

2.1. Molecular Docking Analysis

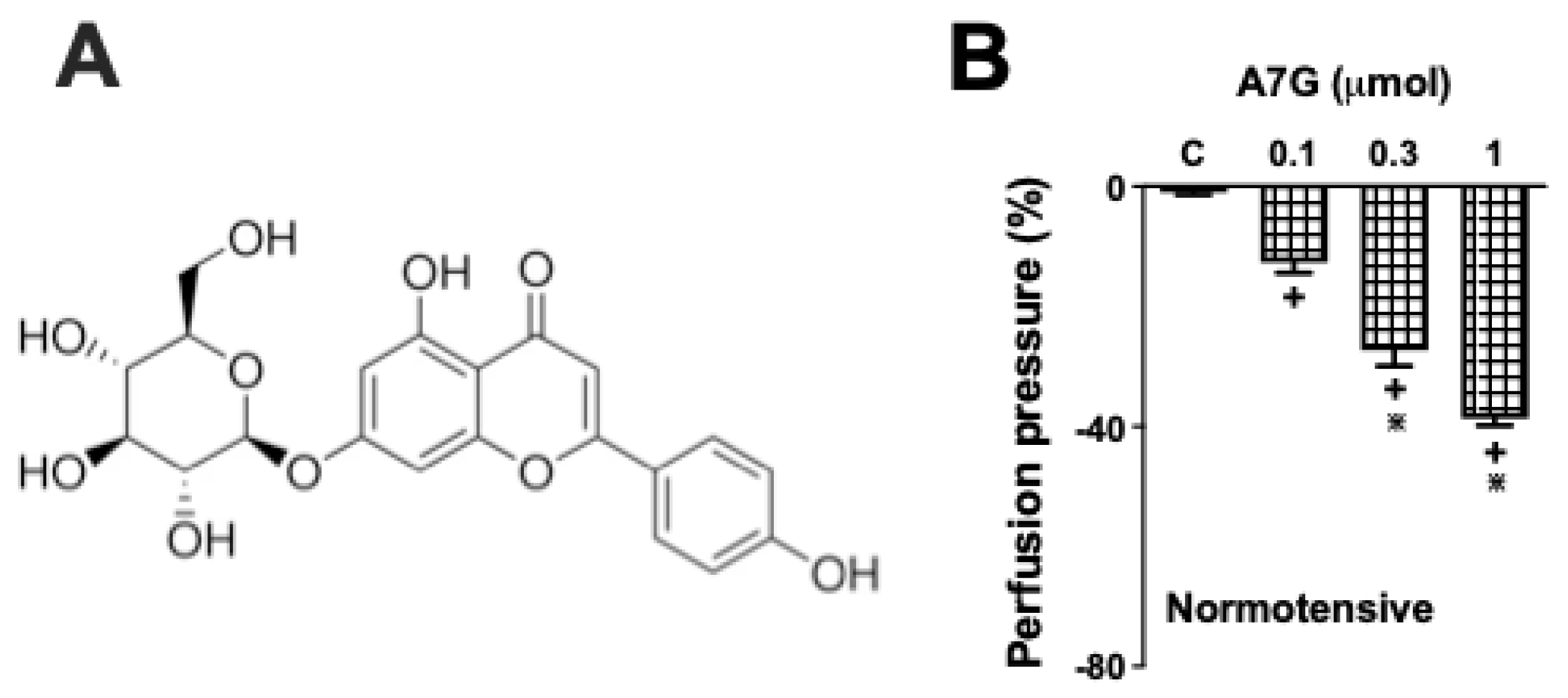

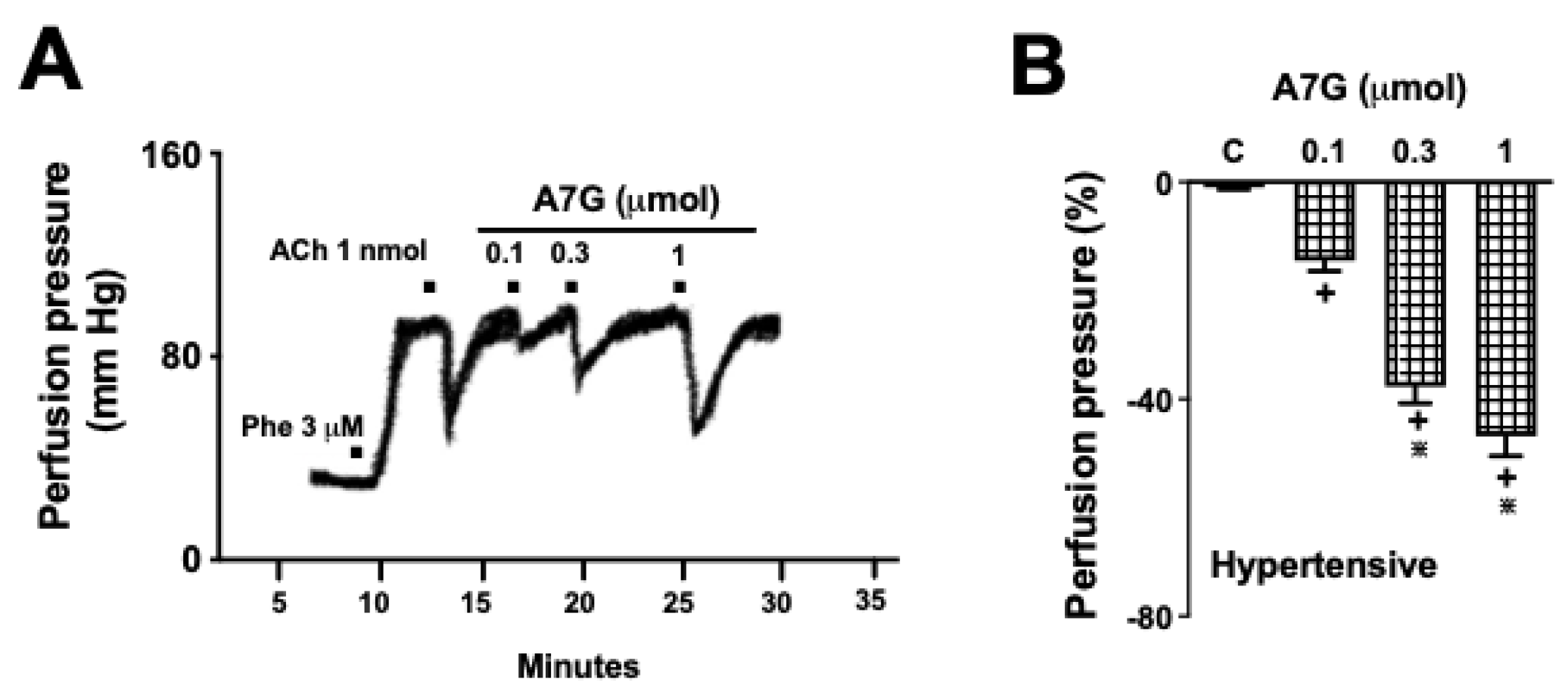

2.2. A7G Induces Vasodilation in the MVBs of WKY and SHR Rats

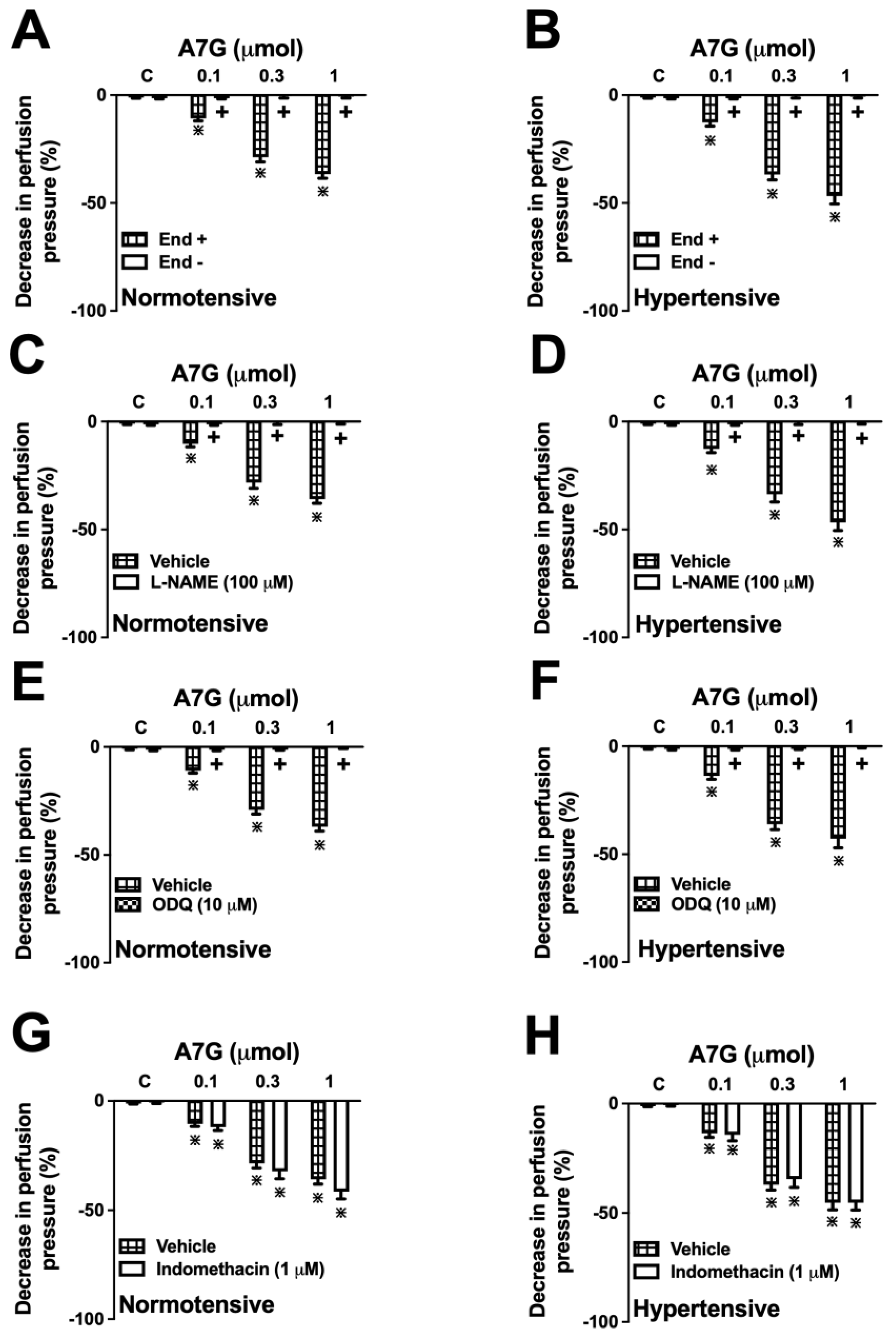

2.3. Involvement of the Vascular Endothelium and the Nitric Oxide (NO)-Soluble Guanylate Cyclase (sGC)-Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate (cGMP) Pathway in the A7G-Induced Vasodilation in the MVBs of WKY and SHR Rats

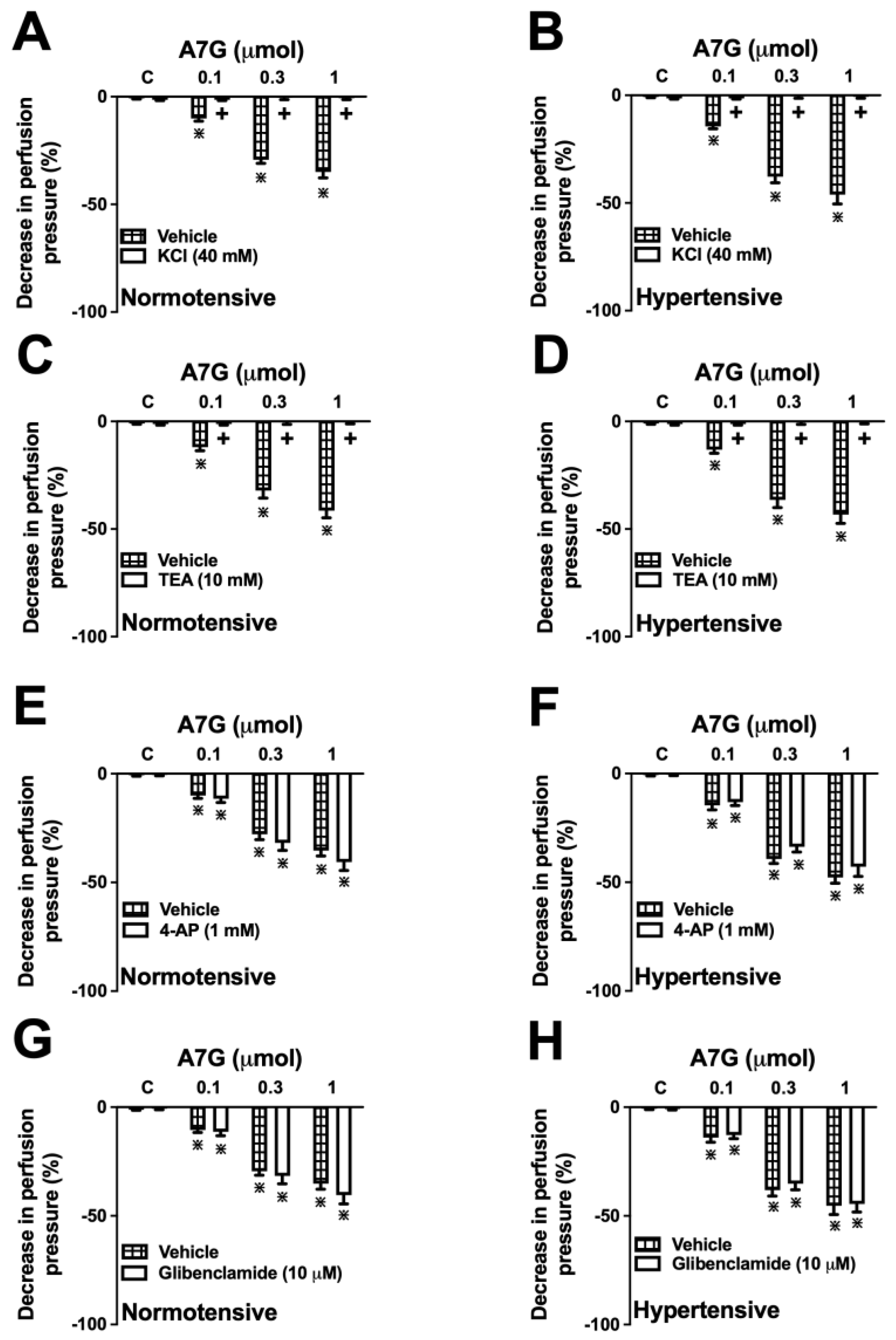

2.4. Involvement of K+ Channels in the A7G-Induced Vasodilation in the MVBs of WKY and SHR Rats

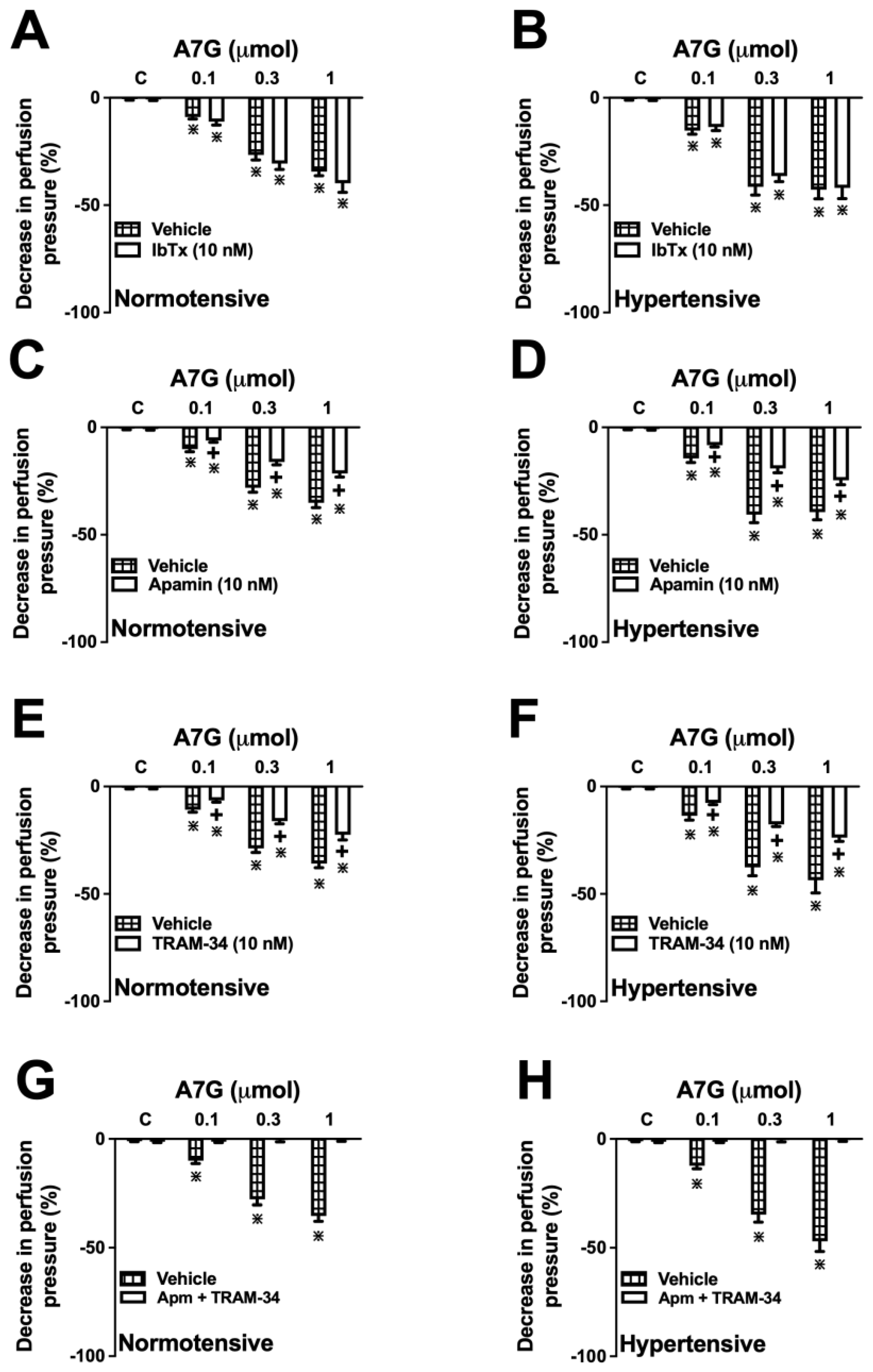

2.5. The Vascular Effect of A7G Is Mediated by the Activation of Intermediate-(IKCa) and Small-Conductance (SKCa) Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels in MVBs from WKY and SHR Rats

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Molecular Docking Studies

4.2. Pharmacological Assays

4.2.1. Drugs and Reagents

4.2.2. Animals

4.2.3. Mesenteric Vascular Bed Preparation

4.2.4. Investigation of the Mechanisms Underlying A7G-Induced Vasodilation

- L-NAME (100 µM), a non-selective NOS inhibitor;

- Indomethacin (1 µM), a non-selective COX inhibitor;

- ODQ (10 µM), a selective inhibitor of sGC.

- KCl (40 mM);

- TEA (10 mM), a non-specific K+ channel blocker;

- Glibenclamide (10 µM), a KATP channel blocker;

- 4-Aminopyridine (100 µM), a Kv channel blocker;

- IbTX (10 nM), a BKCa channel blocker;

- TRAM-34 (10 nM), a IKCa channel blocker;

- Apamin (10 nM), a SKCa channel blocker.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVDs | Cardiovascular diseases |

| A7G | Apigenin 7-glucoside |

| eNOS | Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| BKCa | Large-conductance Calcium-activated Potassium Channel |

| Kv | Voltage-gated K+ channels |

| KATP | ATP-sensitive potassium channels |

| MVBs | Mesenteric Vascular Beds |

| cGMP | Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate |

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| L-NAME | Nω-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester |

| PGI2 | Prostacyclin |

| TEA | Tetraethylammonium |

| IbTX | Iberiotoxin |

| PSS | Physiological Saline Solution |

| SHR | Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats |

| FQ | Fit Quality |

| LE | Ligand Efficiency |

| BEI | Binding Efficiency Index |

| Ki | Inhibition Constant |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| SKCa | Small-conductance Calcium-activated Potassium Channel |

| IKCa | Intermediate-conductance Calcium-activated Potassium Channel |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| TRAM-34 | Selective IKCa channel blocker |

| ODQ | 1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazolo[4,2-alpha]quinoxalin-1-one |

References

- Chen, C.; Li, X.; Su, Y.; You, Z.; Wan, R.; Hong, K. Adherence with cardiovascular medications and the outcomes in patients with coronary arterial disease: “Real-world” evidence. Clin. Cardiol. 2022, 45, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, C.; Sciatti, E.; Favero, G.; Bonomini, F.; Vizzardi, E.; Rezzani, R. Essential Hypertension and Oxidative Stress: Novel Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, A.; Mazzapicchi, A.; Baiardo Redaelli, M. Systemic and Cardiac Microvascular Dysfunction in Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, T.D.; Sander, G.E.; Nossaman, B.D.; Kadowitz, P.J. Impaired vasodilation in the pathogenesis of hypertension: Focus on nitric oxide, endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factors, and prostaglandins. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2012, 14, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tare, M.; Parkington, H.C.; Coleman, H.A. EDHF, NO and a prostanoid: Hyperpolarization-dependent and -independent relaxation in guinea-pig arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 130, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmashankar, K.; Widlansky, M.E. Vascular endothelial function and hypertension: Insights and directions. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2010, 12, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulluce, M.; Orhan, F.; Yanmis, D.; Arasoglu, T.; Guvenalp, Z.; Demirezer, L.O. Isolation of a flavonoid, apigenin 7-O-glucoside, from Mentha longifolia (L.) Hudson subspecies longifolia and its genotoxic potency. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2015, 31, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanske, L.; Loh, G.; Sczesny, S.; Blaut, M.; Braune, A. The bioavailability of apigenin-7-glucoside is influenced by human intestinal microbiota in rats. J. Nutr. 2009, 1, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klider, L.M.; da Silva, M.L.F.; da Silva, G.R.; da Costa, J.R.C.; Marques, M.A.A.; Lourenço, E.L.B.; Lívero, F.A.D.R.; Manfron, J.; Gasparotto Junior, A. Nitric Oxide and Small and Intermediate Calcium-Activated Potassium Channels Mediate the Vasodilation Induced by Apigenin in the Resistance Vessels of Hypertensive Rats. Molecules 2024, 29, 5425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Ren, B.; Wang, S.; Liang, S.; He, B.; Shi, X.; Wang, L.; Liang, J.; Wu, F. Apigenin and naringenin ameliorate PKCbetaII-associated endothelial dysfunction via regulating ROS/caspase-3 and NO pathway in endothelial cells exposed to high glucose. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2016, 85, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Yang, G.; Xi, D.; Qin, X.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Apigenin prevents hypertensive vascular remodeling by regulating the TP53 pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 157, 114706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.E.; Allen, S.; Chang, A.P.; Henderson, H.; Hobson, G.C.; Karania, B.; Morgan, K.N.; Pek, A.S.; Raghvani, K.; Shee, C.Y.; et al. Distinct mechanisms of relaxation to bioactive components from chamomile species in porcine isolated blood vessels. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 272, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Y.; Chen, R.; Dong, M.; Liu, Y.; Hou, X.; Guo, P.; Li, W.; Lv, J.; Zhang, M. Apigenin relaxes rat intrarenal arteries, depresses Ca2+-activated Cl− currents and augments voltage-dependent K+ currents of the arterial smooth muscle cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 115, 108926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yue, R.F.; Jin, Z.; He, L.M.; Shen, R.; Du, D.; Tang, Y.Z. Efficiency comparison of apigenin-7-O-glucoside and trolox in antioxidative stress and anti-inflammatory properties. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2020, 72, 1645–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, J.; Milbradt, R. Skin anti-inflammatory activity of apigenin-7-glucoside in rats. Arzneim.-Forsch. 1993, 43, 370–372. [Google Scholar]

- Farhat, A.; Ben Hlima, H.; Khemakhem, B.; Ben Halima, Y.; Michaud, P.; Abdelkafi, S.; Fendri, I. Apigenin analogues as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: In-silico screening approach. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 3350–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.S.; Sun, X.L.; Xu, B.; Li, G.; Song, M. Mechanisms of apigenin-7-glucoside as a hepatoprotective agent. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2005, 18, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Man, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y. Apigenin 7-glucoside impedes hypoxia-induced malignant phenotypes of cervical cancer cells in a p16-dependent manner. Open Life Sci. 2024, 19, 20220819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.M.; Ma, R.H.; Ni, Z.J.; Thakur, K.; Cespedes-Acuña, C.L.; Jiang, L.; Wei, Z.J. Apigenin 7-O-glucoside promotes cell apoptosis through the PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway and inhibits cell migration in cervical cancer HeLa cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 146, 111843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Bhat, Z.A. Apigenin 7-glucoside from Stachys tibetica Vatke and its anxiolytic effect in rats. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnashi, M.H.; Ayaz, M.; Alqahtani, Y.S.; Alyami, B.A.; Shahid, M.; Alqahtani, O.; Kabrah, S.M.; Zeb, A.; Ullah, F.; Sadiq, A. Quantitative-HPLC-DAD polyphenols analysis, anxiolytic and cognition enhancing potentials of Sorbaria tomentosa Lindl. Rehder. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 317, 116786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozyra, M.; Biernasiuk, A.; Wiktor, M.; Kukula-Koch, W.; Malm, A. Comparative HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF/MS/MS Analysis of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds Content in the Methanolic Extracts from Flowering Herbs of Monarda Species and Their Free Radical Scavenging and Antimicrobial Activities. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harahap, U.; Syahputra, R.A.; Ahmed, A.; Nasution, A.; Wisely, W.; Sirait, M.L.; Dalimunthe, A.; Zainalabidin, S.; Taslim, N.A.; Nurkolis, F.; et al. Current Insights and Future Perspectives of Flavonoids: A Promising Antihypertensive Approach. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 3146–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konukoglu, D.; Uzun, H. Endothelial Dysfunction and Hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 956, 511–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q. Research Progress of Flavonoids Regulating Endothelial Function. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, T.-C.; Yen, M.-H.; Li, C.-Y.; Ding, Y.-A. Alterations of Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression with Aging and Hypertension in Rats. Hypertension 1998, 31, 643–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Shi, L. BKCa Channel Activity and Vascular Contractility Alterations with Hypertension and Aging via Β1 Subunit Promoter Methylation in Mesenteric Arteries. Hypertens. Res. 2018, 41, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.; Baez-Nieto, D.; Valencia, I.; Oyarzún, I.; Rojas, P.; Naranjo, D.; Latorre, R. K+ Channels: Function-Structural Overview. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 2087–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter-Laskowska, M.; Trybek, P.; Delfino, D.V.; Wawrzkiewicz-Jałowiecka, A. Flavonoids as Modulators of Potassium Channels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayden, J.E. Potassium Channels in Vascular Smooth Muscle. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1996, 23, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, D.A.; Morais Cabral, J.; Pfuetzner, R.A.; Kuo, A.; Gulbis, J.M.; Cohen, S.L.; Chait, B.T.; MacKinnon, R. The Structure of the Potassium Channel: Molecular Basis of K+ Conduction and Selectivity. Science 1998, 280, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordi, R.; Fernandes, D.; Heckert, B.; Assreuy, J. Early Potassium Channel Blockade Improves Sepsis-Induced Organ Damage and Cardiovascular Dysfunction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1289–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.C.; Ke, W.H.; Ceng, L.H.; Hsieh, C.W.; Wung, B.S. Calcium- and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by apigenin. Life Sci. 2010, 87, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, D.D. The Effect of Sympathetic Nerve Stimulation on Vasoconstrictor Responses in Perfused Mesenteric Blood Vessels of the Rat. J. Physiol. 1965, 177, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.L.F.; Aytar, E.C.; Gasparotto Junior, A. Vasodilator Effects of Quercetin 3-O-Malonylglucoside Are Mediated by the Activation of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase and the Opening of Large-Conductance Calcium-Activated K+ Channels in the Resistance Vessels of Hypertensive Rats. Molecules 2025, 30, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Protein | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | LE | FQ | BEI | Estimated Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A7G | 1M9M | −9.7 | 0.313 | 0.855 | 0.024 | 0.076 |

| A7G | 6CNN | −8.5 | 0.274 | 0.776 | 0.019 | 0.581 |

| A7G | 9ED1 | −8.4 | 0.271 | 0.767 | 0.019 | 0.688 |

| Compound | Protein | H-Bond | Pi–Pi Stacking | Alkyl Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A7G | 1M9M | ARG352:HH12–O4 ARG189:HH21–O5 PHE190:HN–O7 ARG191:HH12–O10 ARG191:HH22–O10 LYS75:HZ3–O9 H4–PHE190:O H7–ALA184:O H17–ASP78:OD2 | ARG180 (π–Cation) ASP78 (π–Anion) | ARG189 (π–Alkyl × 2) ALA184 (π–Alkyl) LYS75 (π–Alkyl) |

| A7G | 6CNN | PHE190:HN–O7 ARG352:HH21–O1 ARG352:HH22–O6 H1–GLU83:OE1 H2–GLU83:OE1 H3–ALA184:O H4–VAL188:O H7–ASN349:OD1 H17–LYS77:O H16–GLU83:OE1 (C-H bond) ARG189:NH2 | ARG180 (π–Cation) ARG189 (π–Cation; π-Donor H-Bond) ARG189:HG1 (π–Sigma) | ARG189 (π–Alkyl) |

| A7G | 9ED1 | HIS461:HD1–O10 H1–PHE460:O H2–SER102:O H3–SER102:O H4–O7 H7–PRO450:O PRO451:HD2–O7 (C–H) TRP74:HD1–O2 (C–H) GLU463:HA–O3 (C–H) H14–SER102:O (C–H) H15–PHE460:O (C–H) H20–PHE460:O (C–H) | ARG365 (π–Cation) ALA446 (π–Lone Pair) | ALA446 (π–Alkyl) PRO451 (π–Alkyl) VAL449 (π–Alkyl) VAL449 (π–Alkyl, chain B) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Silva, M.L.F.; Aytar, E.C.; Gasparotto Junior, A. The Role of the NO/cGMP Pathway and SKCa and IKCa Channels in the Vasodilatory Effect of Apigenin 7-Glucoside. Molecules 2025, 30, 4265. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214265

da Silva MLF, Aytar EC, Gasparotto Junior A. The Role of the NO/cGMP Pathway and SKCa and IKCa Channels in the Vasodilatory Effect of Apigenin 7-Glucoside. Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4265. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214265

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Silva, Maria Luiza Fidelis, Erdi Can Aytar, and Arquimedes Gasparotto Junior. 2025. "The Role of the NO/cGMP Pathway and SKCa and IKCa Channels in the Vasodilatory Effect of Apigenin 7-Glucoside" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4265. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214265

APA Styleda Silva, M. L. F., Aytar, E. C., & Gasparotto Junior, A. (2025). The Role of the NO/cGMP Pathway and SKCa and IKCa Channels in the Vasodilatory Effect of Apigenin 7-Glucoside. Molecules, 30(21), 4265. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214265