GC/MS and PCA Analysis of Volatile Compounds Profile in Various Ilex Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. HD-SPME-GC/MS Profiles of Ilex spp. Volatile Components

2.2. Statistical Analysis

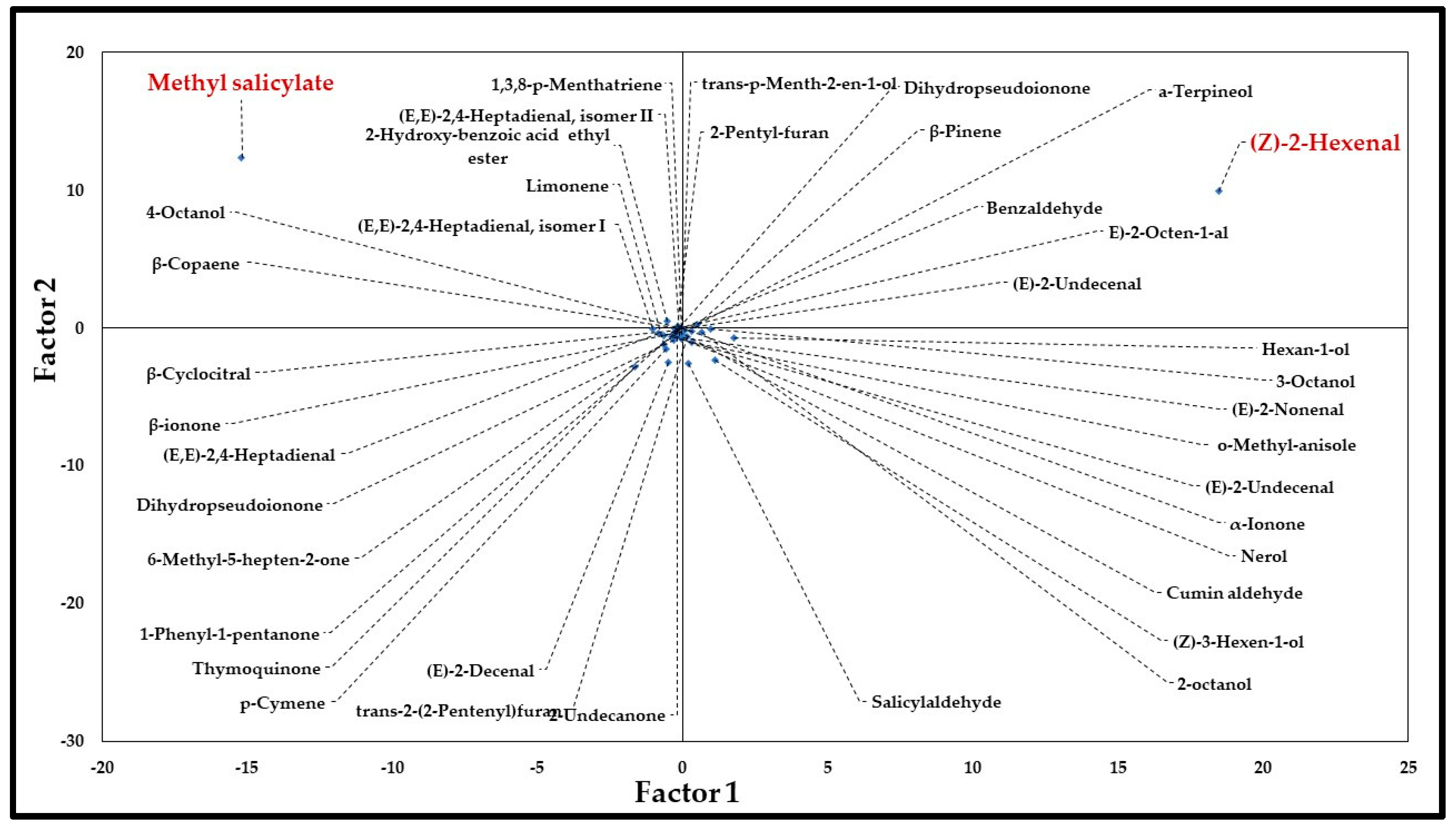

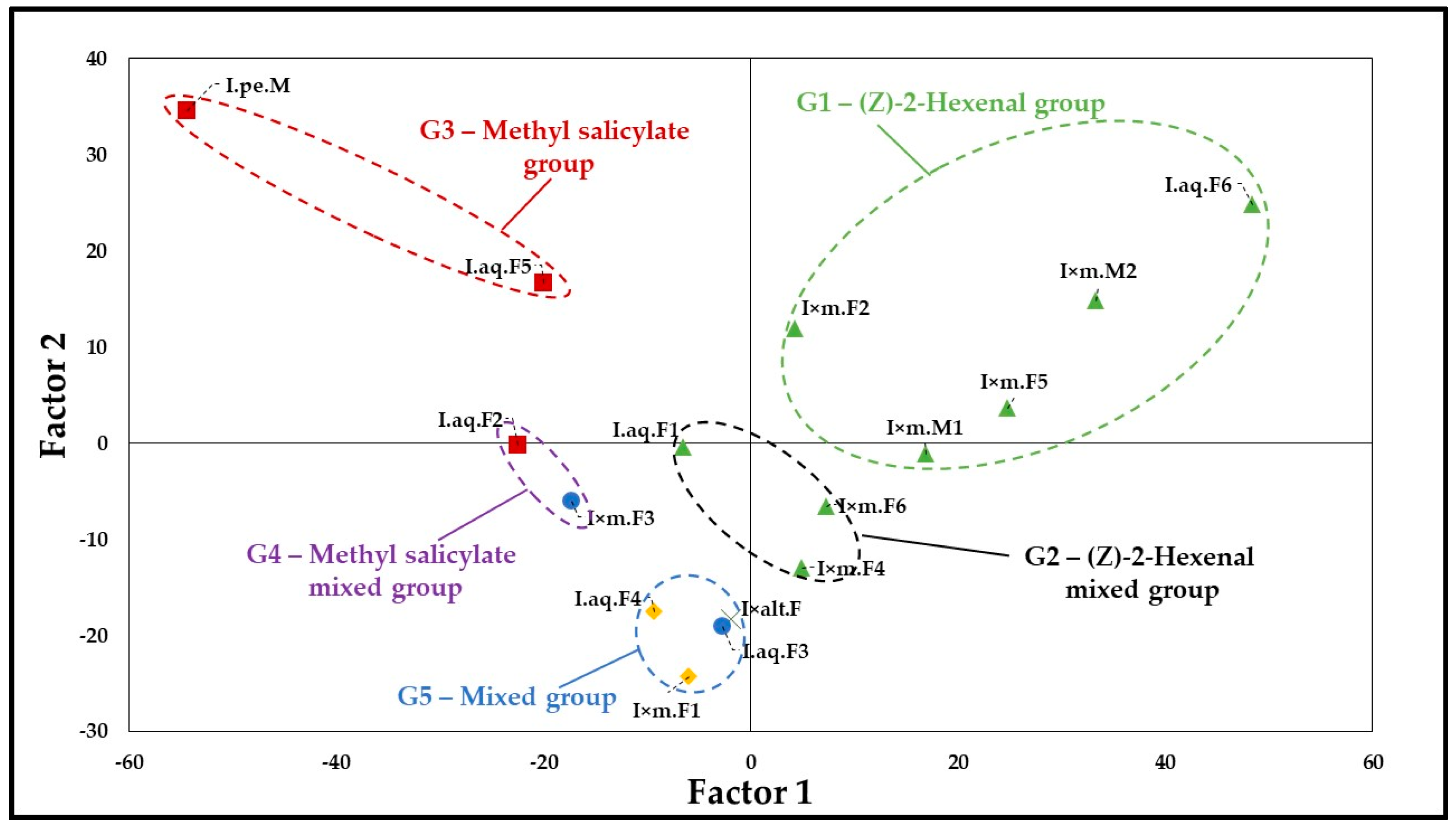

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

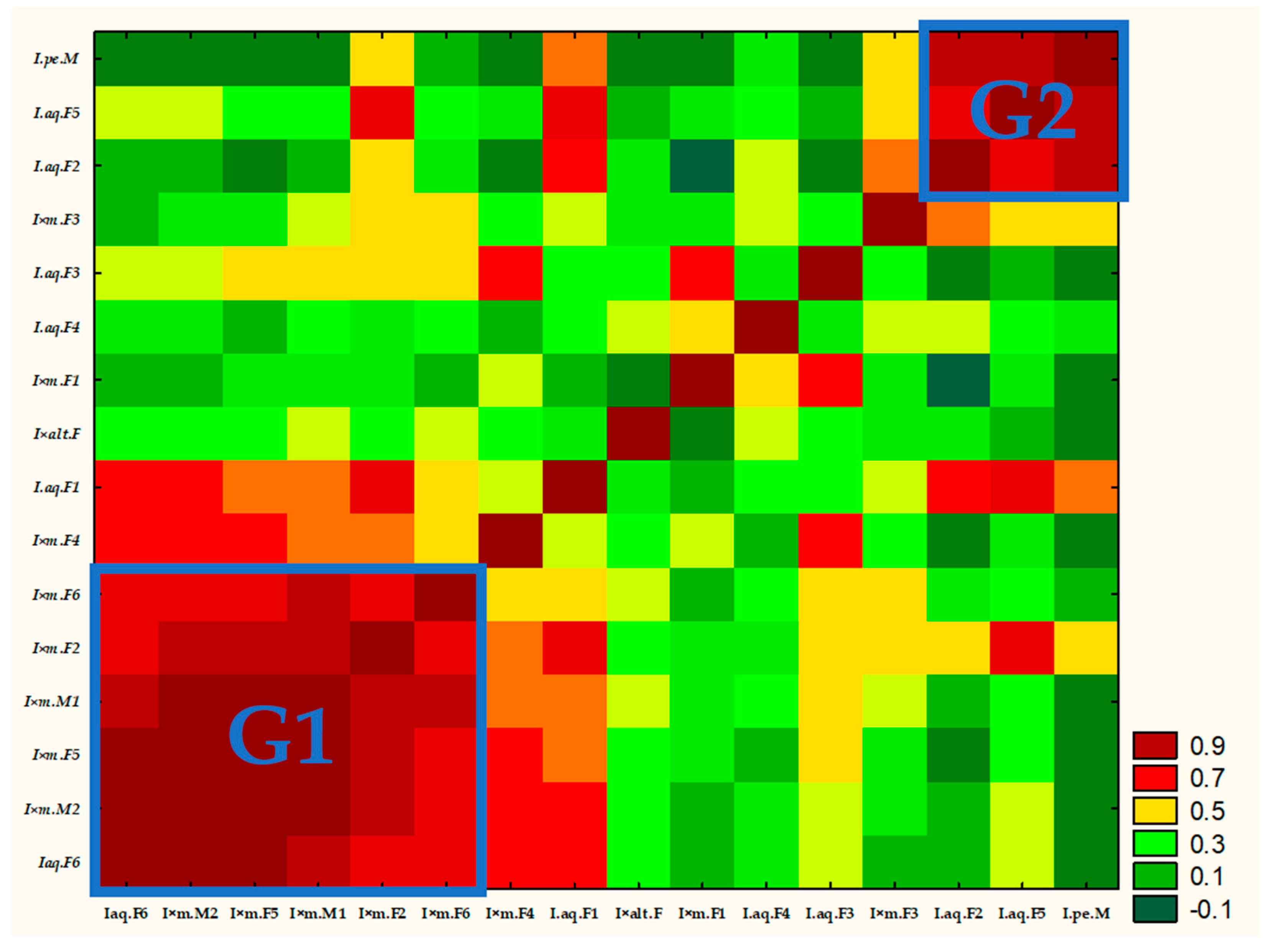

2.3. Correlation Matrix Heat Map and Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (Dendrogram)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Chemical Composition of Samples

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yao, X.; Song, Y.; Yang, J.B.; Tan, Y.H.; Corlett, R.T. Phylogeny and biogeography of the hollies (Ilex L., Aquifoliaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2021, 59, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Zhao, X.; Peng, Y.; Xiao, P. Genus llex L.: Phytochemistry, Ethnopharmacology, and Pharmacology. Chin. Herbal. Med. 2016, 8, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcaro, G.; Tranchida, P.Q.; Jacques, R.A.; Caramão, E.B.; Moret, S.; Conte, L.; Dugo, P.; Dugo, G.; Mondello, L. Characterization of the yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) volatile fraction using solid-phase microextraction-comprehensive 2-D GC-MS. J. Sep. Sci. 2009, 32, 3755–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Li, J.J.; Guo, D.Q.; Du, H.H. Complete chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of Ilex pernyi Franch. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2021, 6, 3477–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salejda, A.M.; Szmaja, A.; Bobak, Ł.; Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A.; Fudali, A.; Bąbelewski, P.; Bienkiewicz, M.; Krasnowska, G. Effect of Ilex × meserveae aqueous extract on the quality of dry-aged beef. J. Food Qual. 2021, 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, V.; Martínez, N.; Guerra, M.; Fariña, L.; Boido, E.; Dellacassa, E. Characterization of aroma-impact compounds in yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) using GC-olfactometry and GC-MS. Food Res. Int. 2013, 53, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, M.; Kobayashi, A. Volatile Constituents of Green Mate and Roasted Mate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1991, 39, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.F.; Gu, H.P.; Kang, W.Y. Analysis of volatiles in the male flower of Ilex cornuta by HS-SPME-GC-MS. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013, 49, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, H.C.; Lacerda, M.E.G.; Lopes, D.; Bizzo, H.R.; Kaplan, M.A. Studies on the aroma of maté (Ilex paraguariensis St. Hil.) using headspace solid-phase microextraction. Phytochem. Anal. 2007, 18, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, F.C. Hollies. The Genus Ilex; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A.; Jarosz, B.; Okińczyc, P.; Szperlik, J.; Bąbelewski, P.; Zadák, Z.; Jankowska-Mąkosa, A.; Knecht, D. GC-MS and PCA Analysis of Fatty Acid Profile in Various Ilex Species. Molecules 2024, 29, 4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, D.D. Volatile Metabolites. Metabolites 2011, 1, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachura, N.; Kupczyński, R.; Sycz, J.; Kuklińska, A.; Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A.; Wińska, K.; Owczarek, A.; Kuropka, P.; Nowaczyk, R.; Bąbelewski, P.; et al. Biological Potential and Chemical Profile of European Varieties of Ilex. Foods 2022, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, E.; Okińczyc, P.; Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A.; Szperlik, J.; Żarowska, B.; Duda-Madej, A.; Bąbelewski, P.; Włodarczyk, M.; Wojtasik, W.; Kupczyński, R.; et al. Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Ilex Leaves Water Extracts. Molecules 2021, 26, 7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuropka, P.; Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A.; Kupczyński, R.; Włodarczyk, M.; Szumny, A.; Nowaczyk, R.M. The Effect of Ilex × meserveae S. Y. Hu Extract and Its Fractions on Renal Morphology in Rats Fed with Normal and High-Cholesterol Diet. Foods 2021, 10, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwyrzykowska, A.; Kupczyński, R.; Jarosz, B.; Szumny, A.; Kucharska, A.Z. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of polyphenolic compounds in Ilex sp. Open Chem. 2015, 13, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wang, S.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, H.; Jiang, L.; McLamore, E.S.; Shen, Y. The WRKY46-MYC2 module plays a critical role in E-2-hexenal-induced anti-herbivore responses by promoting flavonoid accumulation. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrignani, F.; Iucci, L.; Belletti, N.; Gardini, F.; Guerzoni, M.E.; Lanciotti, R. Effects of sub-lethal concentrations of hexanal and 2-(E)-hexenal on membrane fatty acid composition and volatile compounds of Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella enteritidis and Escherichia coli. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 123, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanciotti, R.; Gianotti, A.; Patrignani, F.; Belletti, N.; Guerzoni, M.E.; Gardini, F. Use of natural aroma compounds to improve shelf-life and safety of minimally processed fruits. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2004, 15, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulou, E.A.; Dekker, H.L.; Steemers, L.; van Maarseveen, J.H.; de Koster, C.G.; Haring, M.A.; Schuurink, R.C.; Allmann, S. Identification and Characterization of (3Z):(2E)-Hexenal Isomerases from Cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Wang, X.; Fu, M.; Cheng, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Sun, F. (E)-2-hexenal regulates the chloroplast degradation in tomatoes. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 318, 112093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondor, O.K.; Pál, M.; Janda, T.; Szalai, G. The role of methyl salicylate in plant growth under stress conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 277, 153809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.P.; Yang, Y.; Pichersky, E.; Klessig, D.F. Altering expression of benzoic acid/salicylic acid carboxyl methyltransferase 1 compromises systemic acquired resistance and PAMP-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singewar, K.; Fladung, M.; Robischon, M. Methyl salicylate as a signaling compound that contributes to forest ecosystem stability. Trees 2021, 35, 1755–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llusia, J.; Penuelas, J.; Munné-Bosch, S. Sustained accumulation of methyl salicylate alters antioxidant protection and reduces tolerance of holm oak to heat stress. Physiol. Plant. 2005, 124, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ament, K.; Krasikov, V.; Allmann, S.; Rep, M.; Takken, F.L.; Schuurink, R.C. Methyl salicylate production in tomato affects biotic interactions. Plant J. 2010, 62, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Bai, L.; Xu, X.; Feng, B.; Cao, R.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Xing, W.; Yang, X. The diverse enzymatic targets of the essential oils of Ilex purpurea and Cymbopogon martini and the major components potentially mitigated the resistance development in tick Haemaphysalis longicornis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 208, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yu, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Bai, L.; Song, X.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Pang, B.; Ayiguli, M.; Yang, X. Chemical profiles and enzyme-targeting acaricidal properties of essential oils from Syzygium aromaticum, Ilex chinensis and Citrus limon against Haemaphysalis longicornis (Acari: Ixodidae). Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Sun, X. Application of chemical elicitor (Z)-3-hexenol enhances direct and indirect plant defenses against tea geometrid Ectropis obliqua. BioControl 2016, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Ge, L.; Chen, S.; Sun, X. Enhanced transcriptome responses in herbivore-infested tea plants by the green leaf volatile (Z)-3-hexenol. J. Plant Res. 2019, 132, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Tan, H.; Jian, G.; Zhou, X.; Huo, L.; Jia, Y.; Zeng, L.; Yang, Z. Herbivore-Induced (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol is an Airborne Signal That Promotes Direct and Indirect Defenses in Tea (Camellia sinensis) under Light. J. Agri. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 12608–12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, T.; Zhang, N.; Gao, T.; Zhao, M.; Jin, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Wan, X.; Schwab, W.; Song, C. Glucosylation of (Z)-3-hexenol informs intraspecies interactions in plants: A case study in Camellia sinensis. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1352–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruther, J.; Kleier, S. Plant–plant signaling: Ethylene synergizes volatile emission in Zea mays induced by exposure to (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol. J. Chem. Ecol. 2005, 31, 2217–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cofer, T.M.; Tumlinson, J.H. The carboxylesterase AtCXE12 converts volatile (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate to (Z)-3-hexenol in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiaf119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalliet, G.; Lionnet, C.; Le Bechec, M.; Dutron, L.; Magnard, J.L.; Baudino, S.; Bergougnoux, V.; Jullien, F.; Chambrier, P.; Vergne, P.; et al. Role of petal-specific orcinol O-methyltransferases in the evolution of rose scent. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.K.; Akhtar, T.A.; Widmer, A.; Pichersky, E.; Schiestl, F.P. Identification of white campion (Silene latifolia) guaiacol O-methyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of veratrole, a key volatile for pollinator attraction. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, K.; Li, C.; Zhai, H.; Wang, Y.; Lou, Y.; Xue, W.; Zhou, G. OsRCI-1-Mediated GLVs enhance rice resistance to brown planthoppers. Plants 2024, 13, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Gu, S.H.; Xiao, H.J.; Zhou, J.J.; Guo, Y.Y.; Liu, Z.W.; Zhang, Y.J. The preferential binding of a sensory organ specific odorant binding protein of the alfalfa plant bug Adelphocoris lineolatus AlinOBP10 to biologically active host plant volatiles. J. Chem. Ecol. 2013, 39, 1221–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Dhruw, L.; Sinha, P.; Pradhan, A.; Sharma, R.; Gupta, B. Nutraceuticals, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.Y.; Sultan, S.J.; Al-Najim, A.N.; Sultan, S.M.; Sultan, N.M.; Haddad, M.F.; Saadi, A.M. Synergistic Antifungal Activity of Thymoquinone and Infrared Radiation Against Aspergillus flavus. Int. J. Des. Nat. Ecodyn. 2025, 20, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.R.; Martínez-López, W.; Saraswathy, R. Biotechnology for Toxicity Remediation and Environmental Sustainability; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 227–265. [Google Scholar]

- Ashour, H.; Zafrah, H.; Dafaalla Mohammed, M.E.; Rashed, L.A.; Abbas, A.M.; Kamar, S.S.; ShamsEldeen, A.M. Ferrostatin-1 Partially Suppressed the Anti-Fibrotic Actions of Thymoquinone in a Rat Model of Cholestasis-Induced Liver Injury. Int. J. Morphol. 2025, 43, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Shi, Z.; Yang, L.; Yu, X. Thymol deploys multiple antioxidative systems to suppress ROS accumulation in Chinese cabbage seedlings under saline stress. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnariu, M.; Quispe, C.; Herrera-Bravo, J.; Helon, P.; Kukula-Koch, W.; López, V.; Les, F.; Vergara, C.V.; Alarcón-Zapata, P.; Alarcón-Zapata, B.; et al. The effects of thymoquinone on pancreatic cancer: Evidence from preclinical studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkat, M.A.; Harshita; Pottoo, F.H.; Beg, S.; Rahman, M.; Ahmad, F.J. Nanomedicine for Bioactives: Healthcare Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 471–486. [Google Scholar]

- Bimonte, S.; Albino, V.; Barbieri, A.; Tamma, M.L.; Nasto, A.; Palaia, R.; Molino, C.; Bianco, P.; Vitale, A.; Schiano, R.; et al. Dissecting the roles of thymoquinone on the prevention and the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: An overview on the current state of knowledge. Infect. Agents Cancer 2019, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Shekhar, H.; Sahu, A.; Haque, S.; Kaur, D.; Tuli, H.S.; Sharma, U. Deciphering the anticancer potential of thymoquinone: In-depth exploration of the potent flavonoid from Nigella sativa. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Cho, S.G.; Yi, Z.; Pang, X.; Rodriguez, M.; Wang, Y.; Sethi, G.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Liu, M. Thymoquinone inhibits tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth through suppressing AKT and extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling pathways. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, A.H. Molecular and Therapeutic actions of Thymoquinone: Actions of Thymoquinone; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Almatroodi, S.A.; Almatroudi, A.; Alsahli, M.A.; Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Thymoquinone, an active compound of Nigella sativa: Role in prevention and treatment of cancer. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2020, 21, 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaravadivelu, S.; Raj, S.K.; Kumar, B.S.; Arumugamand, P.; Ragunathan, P.P. Reverse screening bioinformatics approach to identify potential anti breast cancer targets using thymoquinone from neutraceuticals Black Cumin Oil. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, H.; Chen, P.; Wang, G.; Xie, S.; Wang, L.; Lv, J.; Wang, F.; Bilal, M.S.; Khan, A.R.; Rajput, N.A.; et al. Trans-2-decenal inhibits Alternaria alternata through disruption of redox homeostasis and membrane integrity. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavković, F.; Bendahmane, A. Floral phytochemistry: Impact of volatile organic compounds and nectar secondary metabolites on pollinator behavior and health. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202201139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khalili, M.; Pathare, P.B.; Rahman, S.; Al-Habsi, N. Aroma compounds in food: Analysis, characterization and flavor perception. Meas. Food 2025, 18, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, T.; Nunes, A.; Moreira, B.R.; Maraschin, M. Yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis A. St.-Hil.) for new therapeutic and nutraceutical interventions: A review of patents issued in the last 20 years (2000–2020). Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | ERI | LRI | I.aq.F1 | I.aq.F2 | I.aq.F3 | I.aq.F4 | I.aq.F5 | I.aq.F6 | I × m.F1 | I × m.F2 | I × m.F3 | I × m.F4 | I × m.F5 | I × m.F6 | I × m.M1 | I × m.M2 | I × alt.F | I.pe.M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Z)-2-Hexenal | 830 | 827 | 15.32 | 2.95 | 7.70 | 4.16 | 16.30 | 73.80 | 32.68 | 30.96 | 3.56 | 17.11 | 41.40 | 20.86 | 4.70 | 55.24 | 9.27 | 0.28 |

| (Z)-3-Hexen-1-ol | 845 | 839 | 1.31 | 0.05 | 11.03 | 0.31 | 0.67 | 4.15 | 8.70 | 9.66 | 25.95 | 12.68 | 11.74 | 5.74 | 15.03 | 6.91 | 1.97 | 0.33 |

| Hexan-1-ol | 860 | 854 | 2.75 | 1.76 | 10.03 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 2.63 | 9.12 | 10.85 | 1.63 | 1.85 | 10.43 | 15.88 | 3.89 | 3.07 | 2.01 | 0.41 |

| * 2,4-Hexadienal isomer I | 872 | n.d. | 2.38 | 1.40 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.24 | 0.65 | 3.41 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 4.04 | 0.70 | 0.19 | 0.04 |

| 2,4-Hexadienal isomer II | 882 | 877 | 0.67 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.31 | 0 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.02 |

| 2-Methyl-1-hexanol | 915 | 917 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Benzaldehyde | 938 | 942 | 3.37 | 7.99 | 4.25 | 5.35 | 6.20 | 2.70 | 0.22 | 7.36 | 7.79 | 8.35 | 0.14 | 3.79 | 1.98 | 5.85 | 9.23 | 2.29 |

| 4-Octanol | 968 | 972 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.55 | 0.35 | 0.60 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 2.42 | 1.81 | 0.60 | 1.85 | 2.50 | 0.01 |

| β-Pinene | 977 | 973 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 1.79 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 3.24 | 1.11 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 0.17 |

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 972 | 975 | 2.46 | 1.32 | 4.40 | 0.85 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.29 |

| 2,4-Heptadienal, isomer I | 974 | 977 | 4.56 | 8.47 | 0.05 | 5.57 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 1.13 | 3.07 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.57 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 2.67 |

| 2-Pentyl-Furan | 976 | 979 | 2.90 | 0 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.19 | 0.81 | 2.84 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 2.72 | 0 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 1.05 | 2.56 |

| 2,4-Heptadienal, isomer II | 979 | 980 | 3.28 | 10.86 | 0.83 | 2.52 | 0.75 | 0 | 0 | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 1.20 | 0 |

| 3-Octanol | 978 | 982 | 1.04 | 0.32 | 1.12 | 0.62 | 0.91 | 0.55 | 4.08 | 0.28 | 1.00 | 1.16 | 5.09 | 2.33 | 1.00 | 5.50 | 2.84 | 0.19 |

| trans-2-(2-Pentenyl)furan | 983 | 985 | 0.59 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 3.16 | 0.14 | 1.03 | 1.26 | 0.03 | 0.57 | 8.45 | 0 | 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.07 |

| 2-Octanol | 988 | 988 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.19 | 0.93 | 0.01 | 2.44 | 0.19 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 5.85 | 1.32 | 1.33 | 3.24 | 5.15 | 0.09 |

| 1-octanal | 998 | 998 | 1.80 | 0.40 | 10.99 | 1.30 | 0 | 1.36 | 0 | 0.28 | 0.53 | 15.37 | 2.28 | 0 | 11.03 | 0.21 | 0 | 0.07 |

| o-Methyl-anisole, | 1004 | 1006 | 0.61 | 6.37 | 0 | 12.41 | 0.23 | 4.63 | 12.43 | 4.01 | 21.70 | 0 | 0 | 14.54 | 0 | 7.97 | 7.14 | 1.18 |

| p-Cymene | 1016 | 1015 | 5.88 | 1.36 | 5.27 | 2.75 | 1.36 | 0.02 | 1.17 | 0.48 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 1.30 | 0.22 | 10.82 | 0.29 | 1.06 | 0.95 |

| Limonene | 1022 | 1025 | 9.25 | 3.95 | 6.92 | 7.32 | 3.33 | 0.36 | 4.77 | 1.98 | 4.46 | 5.34 | 3.27 | 3.03 | 1.59 | 1.28 | 4.27 | 2.13 |

| (E)-2-Octen-1-al | 1032 | 1035 | 3.29 | 2.80 | 0.04 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.14 | 0.52 | 0.43 |

| trans-Rose oxide | 1112 | 1115 | 0.49 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| trans-p-Menth-2-en-1-ol | 1134 | 1130 | 1.30 | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| 1,3,8-p-Menthatriene | 1116 | 1119 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 4.65 | 2.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.75 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 1.10 | 0.12 | 0.43 | 0 | 0.05 |

| (E)-2-Nonenal | 1130 | 1134 | 0.88 | 0.50 | 2.61 | 2.26 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 5.67 | 0.81 |

| δ-Terpineol | 1145 | 1148 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 0.50 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| Neomentol | 1154 | 1156 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Methyl Salicylate | 1173 | 1171 | 14.49 | 24.31 | 0.95 | 4.08 | 36.62 | 0.00 | 1.25 | 19.05 | 20.57 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 2.73 | 0.29 | 2.26 | 0.21 | 72.83 |

| α-Terpineol | 1175 | 1176 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 2.01 | 0.16 | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 3.57 | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| β-Cyclocitral | 1196 | 1194 | 1.67 | 1.82 | 0.63 | 1.01 | 0.66 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.81 | 0.22 | 1.02 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.53 | 0.16 |

| Nerol | 1212 | 1210 | 0.15 | 0.51 | 1.85 | 3.04 | 2.36 | 0.00 | 2.55 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 3.70 | 2.25 | 1.81 | 1.75 | 0.07 | 4.79 | 0.57 |

| Thymoquinone | 1216 | 1215 | 2.19 | 0.39 | 6.50 | 13.74 | 9.16 | 0.79 | 1.41 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 1.23 | 0.73 | 25.64 | 0.46 | 2.13 | 3.83 |

| Cumin aldehyde | 1219 | 1217 | 0.48 | 0.73 | 0.70 | 2.32 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.65 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.29 |

| β-Homocyclocitral | 1234 | 1236 | 0.07 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.48 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| (E)-2-Decenal, | 1238 | 1240 | 1.60 | 4.66 | 4.98 | 4.50 | 1.75 | 0.05 | 5.65 | 2.39 | 0.61 | 3.47 | 3.27 | 2.71 | 1.61 | 0.18 | 27.95 | 2.49 |

| 2-Hydroxy-benzoic acid ethyl ester | 1251 | 1252 | 1.42 | 0.61 | 0.97 | 0.19 | 9.57 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 1.64 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 1.24 | 0.30 |

| p-Ethyl-benzyl alcohol, - | 1259 | n.d. | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| 2-Undecanone | 1270 | 1273 | 0.99 | 1.67 | 0.23 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.24 |

| Terpinene 4-acetate | 1291 | 1290 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.28 |

| 2-Undecanol | 1300 | 1301 | 2.67 | 2.26 | 2.35 | 4.64 | 1.88 | 0.09 | 1.88 | 0.75 | 0.33 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 0.53 | 3.74 | 0.93 |

| 3-Undecanol | 1305 | 1308 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.04 |

| 1-Phenyl-1-pentanone, | 1325 | 1327 | 0.46 | 1.53 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.58 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

| * (E)-2-undecenal, | 1355 | 1357 | 0.36 | 1.01 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.15 |

| Copaene | 1372 | 1375 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 1.44 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 1.46 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.55 | 0 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Isolongifolene | 1396 | 1394 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 2.14 | 2.62 | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 2.56 | 6.73 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.94 |

| α-Ionone | 1432 | 1411 | 3.00 | 0.85 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.73 | 0.01 | 0.36 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| β-Copaene | 1426 | 1426 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Dihydropseudoionone | 1428 | 1432 | 1.51 | 2.69 | 1.13 | 3.62 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.86 | 0.24 | 0.99 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 1.73 | 0.72 |

| β-ionone | 1461 | 1466 | 1.78 | 2.65 | 1.41 | 1.60 | 0.51 | 0.13 | 0.61 | 1.11 | 0.53 | 1.10 | 0.44 | 2.50 | 0.94 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.15 |

| γ-Guaiene | 1498 | 1499 | 0.72 | 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.70 | 0.27 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.33 |

| δ-Cadinene | 1516 | 1517 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 |

| Sum of components group | ||||||||||||||||||

| non-terpene aliphatic alcohols | 8.45 | 4.73 | 26.45 | 7.14 | 5.68 | 7.57 | 23.24 | 21.95 | 30.43 | 18.58 | 36.57 | 28.55 | 26.4 | 21.12 | 18.35 | 2.01 | ||

| non-terpene aliphatic aldehydes and ketones | 35.79 | 35.7 | 21.58 | 21.1 | 21.14 | 76.39 | 12.23 | 34.99 | 7.61 | 29.51 | 46.12 | 26.24 | 41.18 | 57.03 | 46.29 | 7.42 | ||

| non-terpene aliphatic components | 44.24 | 40.43 | 48.03 | 28.24 | 26.82 | 83.96 | 35.47 | 56.94 | 38.04 | 48.09 | 82.69 | 54.79 | 67.58 | 78.15 | 64.64 | 9.43 | ||

| Aromatic compounds | 25.23 | 40.45 | 17.63 | 27.09 | 52.96 | 10.67 | 14.3 | 32.61 | 51.51 | 35.37 | 3.56 | 22.8 | 18.93 | 16.5 | 18.89 | 79.35 | ||

| Terpenes and terpenoids | 30.05 | 17.67 | 34.28 | 44.09 | 20.1 | 5.38 | 50.16 | 10.38 | 10.24 | 15.96 | 13.74 | 22.15 | 13.45 | 5.23 | 16.4 | 11.13 |

| Abbreviation | Sex | Ilex Species | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|

| I.aq.F1 | F | Ilex aquifolium ‘Alaska’ female variety, very valuable due to the glossy leaves, slow growth and high resistance to low temperatures up to −29 degrees |  |

| I × m.M2 | M | Ilex × meserveae seedling growing in the collection, male individual grown from seeds collected from variety ‘Blue Girl’. |  |

| I × m.F2 | F | Ilex × meserveae ‘Blue Girl’ mother plant growing in the collection, forming red fruits, dense shrub with slow growth |  |

| I × m.F3 | F | Ilex × meserveae ‘Blue Girl’ seeding growing in collection, female shrub |  |

| I.aq.F2 | F | Ilex aquifolium female seedling growing in the collection |  |

| I × m.F4 | F | Ilex × meserveae ‘Golden Girl’ female seedling growing in the foil tunnel, cultivated for collecting shoots for cuttings |  |

| I × m.F5 | F | Ilex × meserveae ‘Blue Girl’ female variety with a dense growth, forming fruits, cultivated in unheated foil tunnel for collecting shoots for cuttings |  |

| I × m.F1 | F | Ilex × meserveae ‘Blue Angel’ female variety with red fruits, slow growth, cultivated in unheated foil tunnel for collecting shoots for cuttings |  |

| I.aq.F6 | F | Ilex aquifolium ‘Pyramidalis Aurea Marginata’ variety with yellow-colored leaves margins with dense, pyramidal growth, cultivated in unheated foil tunnel for collecting shoots for cuttings |  |

| I.aq.F3 | F | Ilex aquifolium ‘Aurea Marginata’ shrubs with yellow-colored leaves margins, red fruits, female individual |  |

| I × alt.F | F | Ilex × altaclarensis ‘Lawsoniana’ a hybrid between Ilex aquifolium and Ilex perado, occurring in Madeira, Canary Island and Azores. Female variety cultivated in unheated foil tunnel due to better wintering of shrubs, which shoots can freeze during cold winters |  |

| I.pe.M | M | Ilex perneyi Franch coming from Mongolia and Northeast China, where it forms high shrubs or low trees up to 7 m. In Poland is not frost-resistant, during cold winters shrubs freeze to the snow surface level |  |

| I.aq.F4 | F | Ilex aquifolium female seedling cultivated in foil tunnel |  |

| I.aq.F5 | F | Ilex aquifolium ‘Alaska’ shrub cultivated in unheated foil tunnel |  |

| I × m.F6 | F | Ilex × meserveae ‘Mesgolg’ shrubs with hard, broadly elliptical leaves length 2–4 cm, sharp top and cuneatic base, with serrated margins (6–8 thorns), nearly flat leaf blade. Dark green top of the blade, bottom light green with blue tone. Variety with female flowers, blooming in the second half of May and on the beginning of June, forms lemon yellow fruits |  |

| I × m.M1 | M | Ilex × meserveae ‘Mesan’ male variety with evergreen leaves, hard, oval or broadly elliptical, with serrated margins (6–9 thorns), glossy top and light green bottom of leaf blade |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A.; Okińczyc, P.; Szperlik, J.; Jarosz, B.; Bąbelewski, P.; Szumny, A.; Zadák, Z.; Jankowska-Mąkosa, A.; Knecht, D. GC/MS and PCA Analysis of Volatile Compounds Profile in Various Ilex Species. Molecules 2025, 30, 4230. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214230

Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska A, Okińczyc P, Szperlik J, Jarosz B, Bąbelewski P, Szumny A, Zadák Z, Jankowska-Mąkosa A, Knecht D. GC/MS and PCA Analysis of Volatile Compounds Profile in Various Ilex Species. Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4230. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214230

Chicago/Turabian StyleZwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, Anna, Piotr Okińczyc, Jakub Szperlik, Bogdan Jarosz, Przemysław Bąbelewski, Antoni Szumny, Zdenek Zadák, Anna Jankowska-Mąkosa, and Damian Knecht. 2025. "GC/MS and PCA Analysis of Volatile Compounds Profile in Various Ilex Species" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4230. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214230

APA StyleZwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A., Okińczyc, P., Szperlik, J., Jarosz, B., Bąbelewski, P., Szumny, A., Zadák, Z., Jankowska-Mąkosa, A., & Knecht, D. (2025). GC/MS and PCA Analysis of Volatile Compounds Profile in Various Ilex Species. Molecules, 30(21), 4230. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214230