Preparation and Performance of Phthalocyanine @ Copper Iodide Cluster Nanoparticles for X-Ray-Induced Photodynamic Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization

2.1.1. Synthesis of Copper Iodide Clusters and Phthalocyanines

2.1.2. Characterization of Copper Iodide Clusters and Phthalocyanines

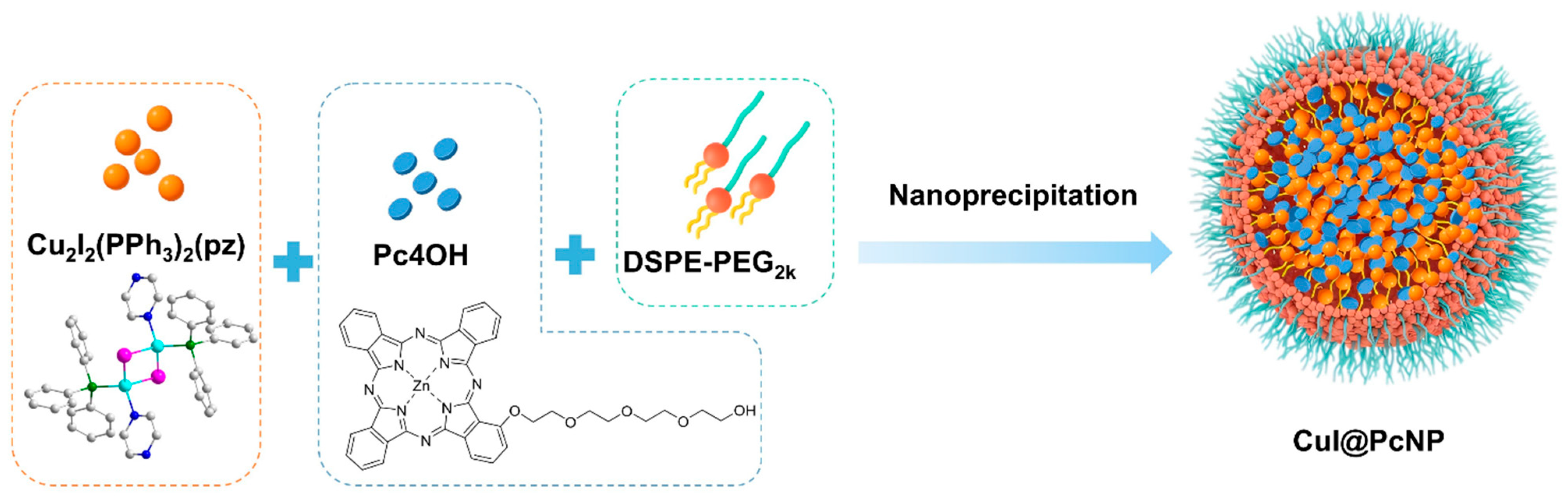

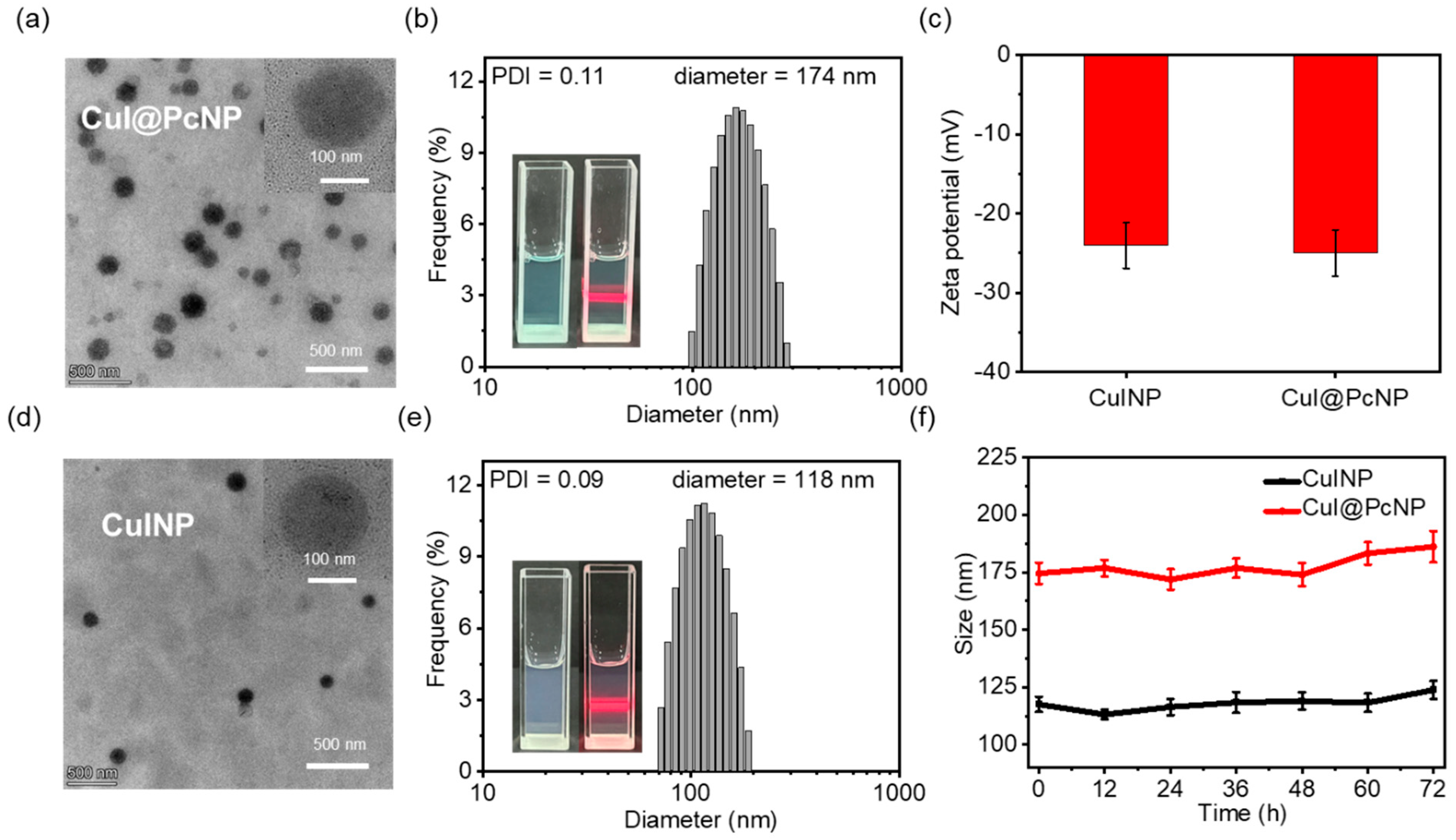

2.1.3. Preparation and Characterization of CuI@PcNP

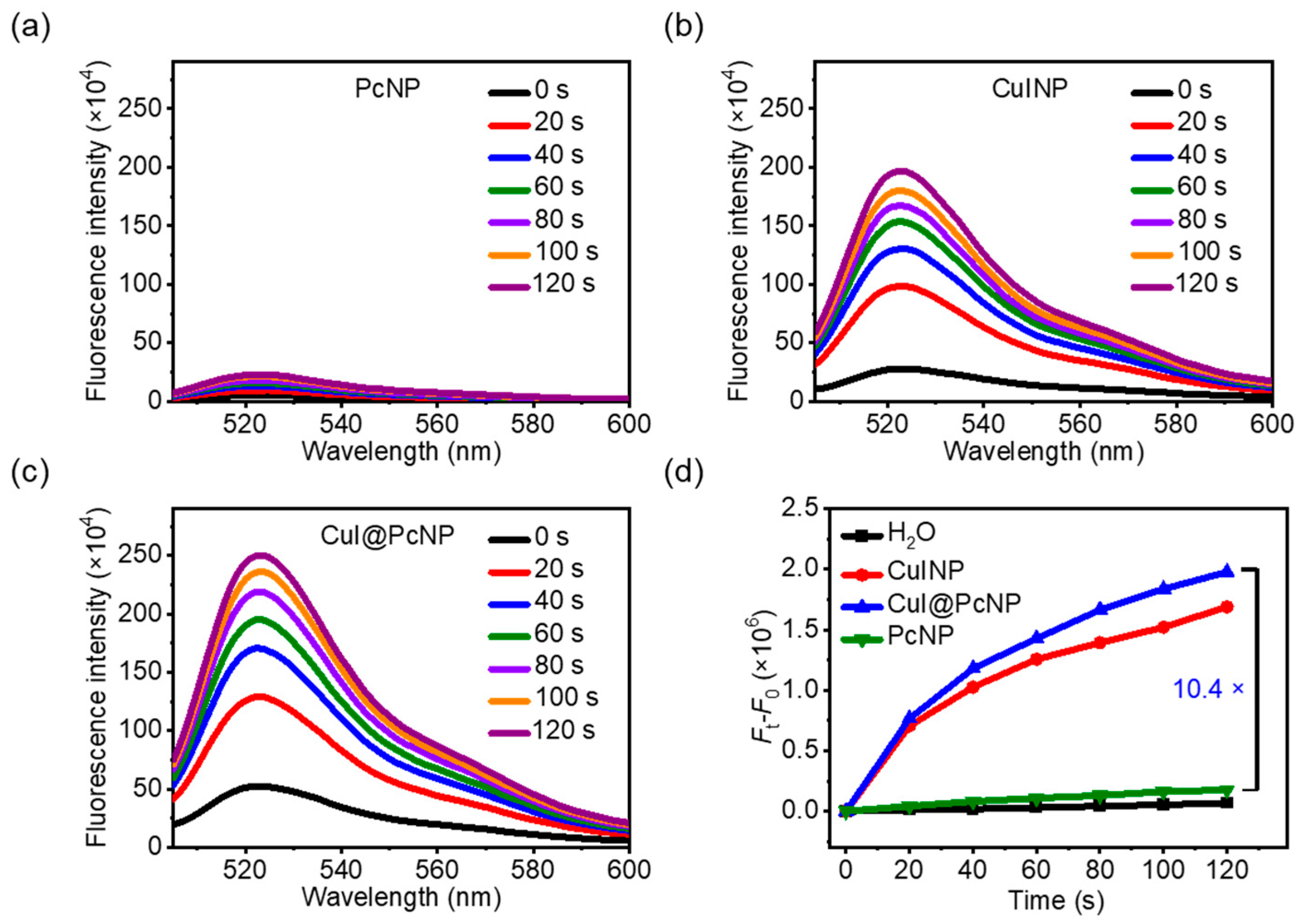

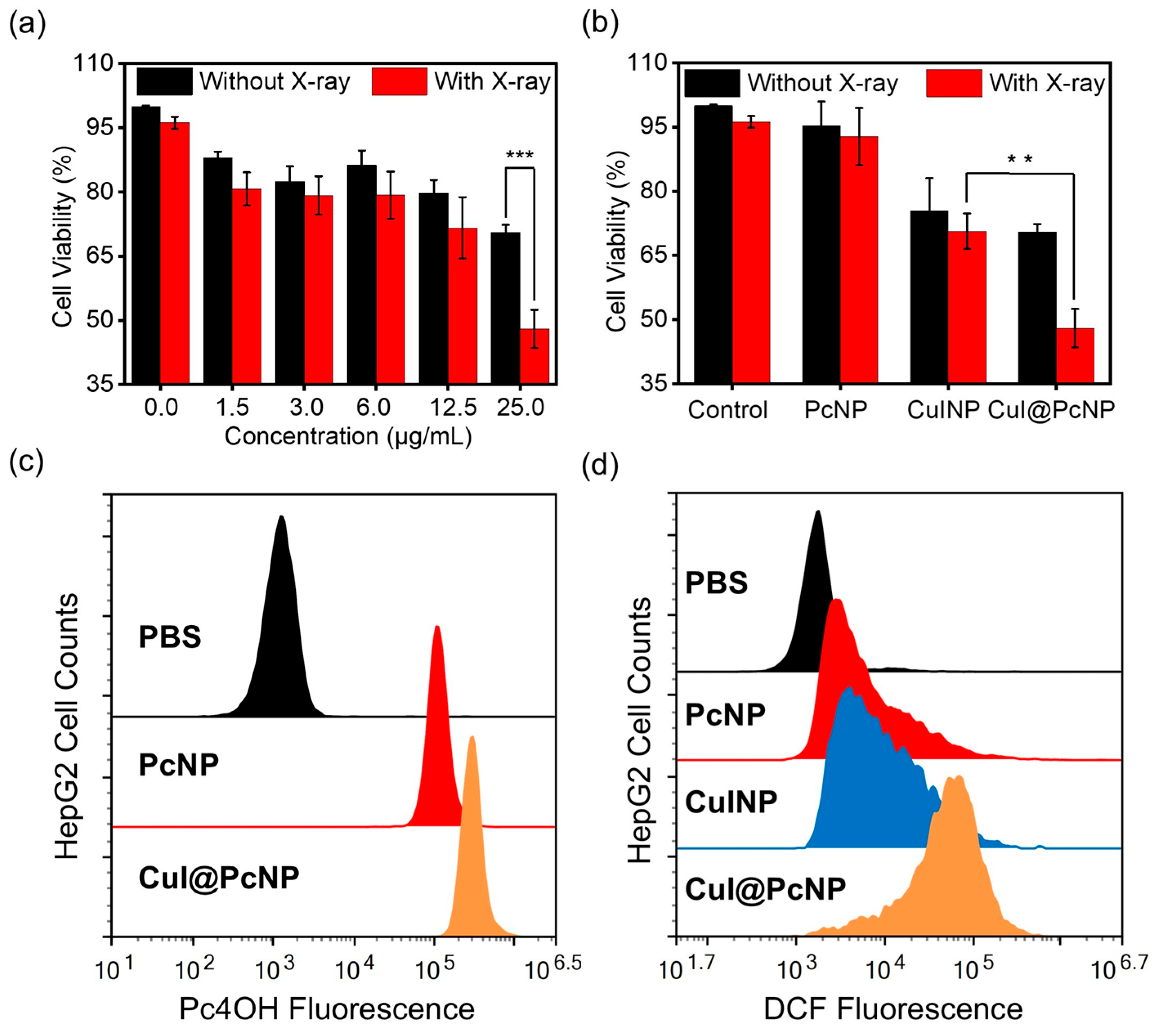

2.2. In Vitro X-PDT Efficacy

2.3. In Vivo Biodistribution and Antitumor Efficacy

2.3.1. In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging and Tumor Accumulation

2.3.2. In Vivo X-PDT Efficacy

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Instruments

3.2. Synthesis of Copper Iodide Clusters

3.2.1. Synthesis of Precursor Cu2I2(3-mpy)4

3.2.2. Synthesis of Precursor Cu2I2(PPh3)2(3-mpy)2

3.2.3. Synthesis of Final Cluster Cu2I2(PPh3)2(pz)

3.3. Synthesis of Phthalocyanines

3.3.1. Synthesis of Precursor PTOH

3.3.2. Synthesis of Phthalocyanines Derivatives (Pc4OH)

3.4. Preparation of CuI@PcNP and Control Formulations

3.5. X-Ray Induced ROS Generation Assay

3.6. Cell Culture

3.6.1. Cellular Uptake

3.6.2. In Vitro Photocytotoxicity

3.7. Animal Experiment

3.7.1. In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging

3.7.2. In Vivo Photodynamic Anticancer Efficacy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shang, L.; Huang, C.C.; Le Guével, X. Luminescent nanomaterials for biosensing and bioimaging. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 3857–3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.D.; Liu, H.T.; Wong, K.L.; All, A.H. Lanthanide-doped upconversion nanoparticles as nanoprobes for bioimaging. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 4650–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ling, J.; Liu, T.Y.; Chen, Z.X. Lumos maxima–How robust fluorophores resist photobleaching? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2024, 79, 102439–102448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Liu, R.; Nel, A.; Gemill, K.B.; Bilal, M.; Cohen, Y.; Medintz, I.L. Meta-analysis of cellular toxicity for cadmium-containing quantum dots. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhong, H.; He, Z.G. Toxicity evaluation of cadmium-containing quantum dots: A review of optimizing physicochemical properties to diminish toxicity. Colloids Surfaces B-Biointerfaces 2021, 200, 111609–111620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.J.; Feng, L.Z.; Shi, G.Y.; Yang, J.N.; Zhang, Y.D.; Xu, H.Y.; Song, K.H.; Chen, T.; Zhang, G.Z.; Zheng, X.S.; et al. High efficiency warm-white light-emitting diodes based on copper-iodide clusters. Nat. Photonics 2024, 18, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.W.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.B.; Xu, G.Z.; Hei, X.Z.; Li, J. Strongly photoluminescent and radioluminescent copper(I) iodide hybrid materials made of coordinated ionic chains. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 1106–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.L.; Zhu, R.Q.; Liu, L.; Zhong, X.X.; Li, F.B.; Zhou, G.J.; Qin, H.M. High-performance TADF-OLEDs utilizing copper(I) halide complexes containing unsymmetrically substituted thiophenyl triphosphine ligands. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 1139–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyano, J.; Zamora, F.; Delgado, S. Copper(I)-iodide cluster structures as functional and processable platform materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 4606–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.Q.; Lin, N.; Yang, Q.; Liu, P.F.; Ding, H.Z.; Xu, M.J.; Ren, F.F.; Shen, Z.Y.; Hu, K.; Meng, S.S.; et al. Biodegradable copper-iodide clusters modulate mitochondrial function and suppress tumor growth under ultralow-dose X-ray irradiation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitorel, B.; El Moll, H.; Utrera-Melero, R.; Cordier, M.; Fargues, A.; Garcia, A.; Massuyeau, F.; Martineau-Corcos, C.; Fayon, F.; Rakhmatullin, A.; et al. Evaluation of Ligands Effect on the Photophysical Properties of Copper Iodide Clusters. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 4328–4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Liu, X.G. A copper-iodide cluster microcube-based X-ray scintillator. Light-Sci. Appl. 2023, 12, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.J.; Wu, Z.Q. Non-destructive testing of mechanical components achieved by hybrid copper-iodide cluster. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 11639–11644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.J.; Zhou, Z.J.; Pratx, G.; Chen, X.Y.; Chen, H.M. Nanoscintillator-mediated X-ray induced photodynamic therapy for deep-seated tumors: From concept to biomedical applications. Theranostics 2020, 10, 1296–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.S.; Lovell, J.F.; Yoon, J.; Chen, X.Y. Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic therapies for cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, C.S.; Yu, J.M.; Zhu, X.H.; Wu, Y.H.; Liu, J.L.; Zhang, Y. Photodynamic-based combinatorial cancer therapy strategies: Tuning the properties of nanoplatform according to oncotherapy needs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 461, 214495–214525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Liu, Z.; Xu, W.; Jin, K.; Liu, J.L.; Zhu, X.H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.H. Towards overcoming obstacles of type II photodynamic therapy: Endogenous production of light, photosensitizer, and oxygen. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 1111–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.D.; Nguyen, H.T.; Chen, H.M.; Cox, P.B.; Wang, L.C.; Nagata, K.; Hao, Z.L.; Wang, A.; Li, Z.B.; Xie, J. X-Ray Induced Photodynamic Therapy: A Combination of Radiotherapy and Photodynamic Therapy. Theranostics 2016, 6, 2295–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.R.; Yu, X.J.; Li, W.W. Recent Progress and Trends in X-ray-Induced Photodynamic Therapy with Low Radiation Doses. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 19691–19721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.J.; Chu, C.C.; Li, S.; Ma, X.Q.; Liu, P.F.; Chen, S.L.; Chen, H.M. Nanosensitizer-mediated unique dynamic therapy tactics for effective inhibition of deep tumors. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 192, 114643–114658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souris, J.S.; Leoni, L.; Zhang, H.J.; Pan, A.R.; Tanios, E.; Tsai, H.M.; Balyasnikova, I.V.; Bissonnette, M.; Chen, C.T. X-ray Activated Nanoplatforms for Deep Tissue Photodynamic Therapy. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.P.; Tang, W.; Lau, J.; Shen, Z.Y.; Xie, J.; Shi, J.L.; Chen, X.Y. Breaking the Depth Dependence by Nanotechnology-Enhanced X-Ray-Excited Deep Cancer Theranostics. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yuan, P.; Yin, J.; Gutiérrez-Arzaluz, L.; Chen, S.L.; Wang, J.X.; Thomas, S.; Alshareef, H.N.; Bakr, O.M.; et al. Copper Iodide Inks for High-Resolution X-ray Imaging Screens. ACS Energy Lett. 2023, 8, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Chen, J.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Zheng, B.Y.; Li, X.S.; Huang, J.D. Copper iodine cluster nanoparticles for tumor-targeted X-ray-induced photodynamic therapy. Sci. China-Mater. 2024, 67, 3358–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, X.Z.; Yang, L.F.; Li, S.C.; Hu, Q.Y.; Li, X.S.; Zheng, B.Y.; Ke, M.R.; Huang, J.D. Size-Tunable Targeting-Triggered Nanophotosensitizers Based on Self-Assembly of a Phthalocyanine-Biotin Conjugate for Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 36435–36443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zheng, B.D.; Peng, X.H.; Li, S.Z.; Ying, J.W.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Huang, J.D.; Yoon, J. Phthalocyanines as medicinal photosensitizers: Developments in the last five years. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 379, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.H.; Sheng, Z.H.; Zhu, M.T.; Wang, X.B.; Yan, F.; Liu, C.B.; Song, L.; Qian, M.; Liu, X.; Zheng, H.R. Forster Resonance Energy Transfer-Based Dual-Modal Theranostic Nanoprobe for Visualization of Cancer Photothermal Therapy. Theranostics 2018, 8, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarbadhikary, P.; George, B.P.; Abrahamse, H. Recent Advances in Photosensitizers as Multifunctional Theranostic Agents for Imaging-Guided Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. Theranostics 2021, 11, 9054–9088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Fang, Y.; Wei, G.Z.; Teat, S.J.; Xiong, K.; Hu, Z.; Lustig, W.P.; Li, J. A Family of Highly Efficient CuI-Based Lighting Phosphors Prepared by a Systematic, Bottom-up Synthetic Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9400–9408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, H.; Tsuge, K.; Sasaki, Y.; Ishizaka, S.; Kitamura, N. Luminescence Ranging from Red to Blue: A Series of Copper(I)−Halide Complexes Having Rhombic {Cu2(μ-X)2} (X = Br and I) Units with N-Heteroaromatic Ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 9667–9675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, R.H.; Zhu, B.S.; Wang, K.H.; Yao, J.S.; Yin, Y.C.; Yao, M.M.; Yao, H.B.; Yu, S.H. Highly Luminescent Inks: Aggregation-Induced Emission of Copper-Iodine Hybrid Clusters. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7106–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.K.; Yao, M.Y.; Lv, H.H.; Jia, X.; Chen, J.J.; Xue, J.P. Novel Targeted Photosensitizer as an Immunomodulator for Highly Efficient Therapy of T-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 15655–15667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.Y.; He, Y.N.; Lv, K.Q.; Ma, H.L. Theoretical study on the origin of the dual phosphorescence emission from organic aggregates at room temperature. Spectrochim. Acta Part A-Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 287, 122077–122081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Zheng, B.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhuang, J.J.; Ke, M.R.; Huang, J.D. Highly photocytotoxic silicon(IV) phthalocyanines axially modified with L-tyrosine derivatives: Effects of mode of axial substituent connection and of formulation on photodynamic activity. Dye. Pigm. 2017, 141, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, W.; Li, Y.; Tang, G.; Li, Z.; Yao, M.; Zheng, B.; Li, X.; Huang, J.-D. Preparation and Performance of Phthalocyanine @ Copper Iodide Cluster Nanoparticles for X-Ray-Induced Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2025, 30, 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214229

Xie W, Li Y, Tang G, Li Z, Yao M, Zheng B, Li X, Huang J-D. Preparation and Performance of Phthalocyanine @ Copper Iodide Cluster Nanoparticles for X-Ray-Induced Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules. 2025; 30(21):4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214229

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Wei, Yunan Li, Guoyan Tang, Zhihua Li, Mengyu Yao, Biyuan Zheng, Xingshu Li, and Jian-Dong Huang. 2025. "Preparation and Performance of Phthalocyanine @ Copper Iodide Cluster Nanoparticles for X-Ray-Induced Photodynamic Therapy" Molecules 30, no. 21: 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214229

APA StyleXie, W., Li, Y., Tang, G., Li, Z., Yao, M., Zheng, B., Li, X., & Huang, J.-D. (2025). Preparation and Performance of Phthalocyanine @ Copper Iodide Cluster Nanoparticles for X-Ray-Induced Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules, 30(21), 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30214229