Abstract

The electrolysis of water for hydrogen production is currently receiving significant attention due to its advantageous features such as non-toxicity, safety, and environmental friendliness. This is especially crucial considering the urgent need for clean energy. However, the current method of electrolyzing water to produce hydrogen largely relies on expensive metal catalysts, significantly increasing the costs associated with its development. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) is considered the most promising alternative to platinum for electrocatalyzing the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) due to its outstanding catalytic efficiency and robust stability. However, the practical application of this material is hindered by its low conductivity and limited exposure of active sites. MoS2/SQDs composite materials were synthesized using a hydrothermal technique to deposit SQDs onto MoS2. These composite materials were subsequently employed as catalysts for the HER. Research findings indicate that incorporating SQDs can enhance electron transfer rates and increase the active surface area of MoS2, which is crucial for achieving outstanding catalytic performance in the HER. The MoS2/SQDs electrocatalyst exhibits outstanding performance in the HER when tested in a 0.5 M H2SO4 solution. It achieves a remarkably low overpotential of 204 mV and a Tafel slope of 65.82 mV dec−1 at a current density of 10 mA cm−2. Moreover, during continuous operation for 24 h, the initial current density experiences only a 17% reduction, indicating high stability. This study aims to develop an efficient and cost-effective electrocatalyst for water electrolysis. Additionally, it proposes a novel design strategy that uses SQDs as co-catalysts to enhance charge transfer in nanocomposites.

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of human civilization, there is an increasing dependence on various forms of energy. Fossil fuels remain a predominant and indispensable energy source in the contemporary world. However, due to the limited availability of fossil fuels and the steadily growing global demand, their scarcity or complete depletion is inevitable [1]. Furthermore, the extensive use of fossil fuels has led to significant degradation of the ecological environment [2,3]. Therefore, the advancement of clean and sustainable energy sources represents a significant challenge for the international community currently [4,5]. Hydrogen has garnered considerable attention as an energy carrier due to its exceptionally high energy density, purity, and renewable characteristics [6]. However, current methods for hydrogen production still heavily rely on fossil fuels, thus inadequately addressing this issue at its root. Alternatively, renewable energy sources can be used to produce high-purity hydrogen sustainably via water electrolysis [7]. However, the efficiency of water electrolysis is significantly reduced due to slow hydrogen evolution reaction kinetics, resulting in a significant increase in costs [8,9]. Noble metal materials, such as platinum-based catalysts, exhibit outstanding electrocatalytic performance for the HER. However, their high cost and limited availability hinder the widespread adoption of these materials. To reduce dependence on platinum-based catalysts, it is crucial to develop novel, cost-effective, and efficient catalysts for the HER that are free from precious metals.

Researchers have thus far concentrated on investigating various transition metal-based materials as potential catalysts for the HER that exhibit exceptional performance [10]. Transition metal-based compounds, particularly those in Group VI B like molybdenum and tungsten, serve as substantial alternatives to precious metals for catalyzing the HER process. Molybdenum-based materials have exhibited excellent performance in the HER, attracting considerable research attention in recent years. Molybdenum-containing compounds exhibit exceptional performance, leading to their extensive application across diverse disciplines, including molecular probes [11], electrochemical capacitors [12], catalysts [13,14], and batteries [15,16]. The investigation into electrochemical HER materials utilizing molybdenum has been ongoing for several decades. Recently, there has been a surge in research exploring various types of molybdenum-based compounds, including alloys, sulfides, selenides, carbides, phosphides, borides, nitrides, and oxides, as highly efficient catalysts for HER. These compounds exhibit substantial electrocatalytic activity and stability across a wide pH range, encompassing strong acids, strong alkalis, and neutral solutions [17]. Transition metal dichalcogenides have become widely recognized as effective electrocatalysts for catalyzing the HER in acidic environments. This is mostly due to their exceptional catalytic efficiency and stability, making them a promising alternative to precious metal catalysts [18,19]. MoS2, one of the transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), is a stable and non-toxic material with a low cost. It shows great promise in the field of electrocatalysis for the HER [20,21]. However, MoS2, extensively researched as a potential alternative to platinum-based HER electrocatalysts, encounters challenges due to its low electrical conductivity and limited accessibility of active sites, which hinder its practical application [22]. Several approaches have been proposed to enhance the reactivity of MoS2, such as enhancing the exposure of active sites, combining it with highly conductive materials, and introducing metal atoms to enhance the intrinsic reactivity of its edges [23,24,25]. For example, research has documented the utilization of Cr-doped FeNi-P nanoparticles and N-doped CoP nanoarrays, both exhibiting significant improvements in their HER capabilities upon the incorporation of chromium (Cr) or nitrogen (N) into the transition metals [26,27]. However, relying solely on elemental doping is insufficient to surpass the performance of Pt and Pt-based materials. Additionally, the presence of a substrate is crucial to offer structural support for transition metal materials [28]. Chen et al. found that incorporating carbon quantum dots (CQDs) onto transition metal phosphide surfaces enhances their performance in the HER by increasing the surface area and the number of active sites [27]. Typically, small 0D nanometer-sized particles (less than 10 nanometers) offer inherent advantages that facilitate their integration into various material structures. The utilization of nanodots, such as CQDs and graphene quantum dots, can significantly enhance electron mobility. Sulphur quantum dots (SQDs) are attracting attention as a promising area of study in electrochemistry, owing to their distinctive characteristics and versatile applications. Nanoscale semiconductor materials typically range in dimensions from 1 to 10 nanometers and exhibit intriguing electrochemical properties due to their adjustable bandgaps, high surface area-to-volume ratio, and exceptional charge transport capabilities. SQDs, or semiconductor quantum dots, demonstrate significant potential across various areas such as energy storage, catalysis, and sensing within the field of electrochemistry. SQDs exhibit high efficiency in conducting redox processes, making them highly suitable for application in batteries, supercapacitors, and electrocatalysis. To date, there are no documented instances of molybdenum-based catalysts being utilized in conjunction with SQDs for HER.

The objective of this study is to attach sulfur quantum dots onto molybdenum disulfide to enhance its electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance. This will be achieved by creating a synergistic catalytic system. The incorporation of sulfur quantum dots has a dual effect: improving the conductivity of molybdenum disulfide and facilitating electron transport. Additionally, it regulates the active sites on the surface of molybdenum disulfide, leading to an enhancement in its electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution capability. Sulfur quantum dots and molybdenum disulfide were synthesized via a hydrothermal process, and composite materials of sulfur quantum dots and molybdenum disulfide were effectively analyzed using various techniques. Subsequently, the electrochemical efficiency of hydrogen production was individually assessed for sulfur quantum dots/molybdenum disulfide, pure molybdenum disulfide, and sulfur quantum dots in an acidic electrolyte. The experimental results demonstrate that the HER performance of the sulfur quantum dots/molybdenum disulfide composite surpasses that of both pure MoS2 and sulfur quantum dots alone, exhibiting a lower onset potential and Tafel slope. The composite material exhibits exceptional durability during stability tests. These results suggest that combining sulfur quantum dots with molybdenum disulfide is a successful approach to improving the electrocatalytic performance of the hydrogen evolution reaction.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Structure Characterization

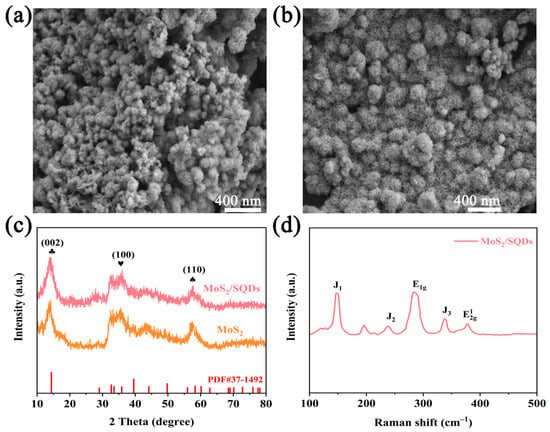

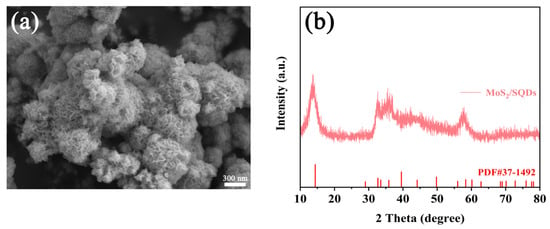

To gain a more comprehensive understanding and conduct a detailed analysis of the structure of MoS2, both before and after the incorporation of SQDs, scanning electron microscopy was employed to investigate the morphology of MoS2. The SEM images of pure MoS2 and MoS2/SQDs are depicted in Figure 1a,b, respectively. These images clearly illustrate the regular and closely arranged structure of MoS2, resembling a rose-like formation. The addition of SQDs has enhanced the aggregation of molybdenum disulfide compared to pure MoS2, resulting in a loosely structured composition comprising several tiny nanosheets. MoS2/SQDs exhibit a greater number of exposed edges compared to pure MoS2, potentially leading to an increased number of active sites available for the HER and consequently enhancing the electrocatalytic activity of MoS2. The XRD graph (Figure 1c) reveals that the diffraction peaks of MoS2 closely match those of standard MoS2 in the PDF card (PDF#37-1492) [28]. Specifically, the (002), (100), and (110) crystal plane peaks are observed at angles of 14.3°, 32.6°, and 58.6°, respectively. The displacement of the diffraction peaks in MoS2/SQDs, compared to pure MoS2, is nearly insignificant. Figure 1d displays the vibration of MoS2/SQDs at 377.46 cm−1, corresponding to in-plane Mo-S vibration, while the E1g peak at 284.30 cm−1 is associated with octahedrally coordinated Mo atoms. Additionally, peaks J1, J2, and J3 at 147.59, 238.73, and 337.97 cm−1, respectively, correspond to the superlattice distortion of the MoS2 basal plane [29].

Figure 1.

(a,b) SEM of MoS2 and MoS2/SQDs; (c) XRD of MoS2 and MoS2/SQDs; (d) Raman spectra of MoS2/SQDs.

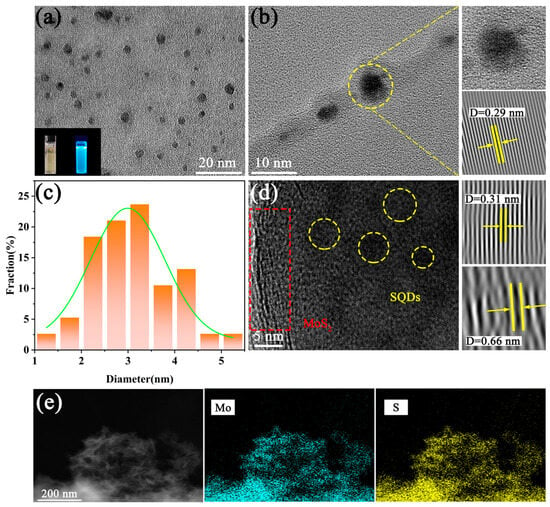

The TEM technique was employed for further characterization. Figure 2a,b present the microstructure of SQDs. Figure 2a illustrates the uniformly distributed and highly spherical crystalline structures of all SQDs. In Figure 2b, a lattice spacing of 0.29 nm in the SQDs is clearly visible, corresponding to the (243) crystal plane. Figure 2c provides the size distribution of SQDs, indicating a size range of 1 nm to 5 nm, directly correlating with the size of the SQDs. TEM images confirm the presence of both MoS2 and SQDs in the sample (Figure 2d). The lattice spacings of 0.31 nm and 0.66 nm observed in the TEM images correspond to the (002) crystal plane of MoS2 and the (243) plane of SQDs, respectively. Additionally, the EDS spectra demonstrate the homogeneous dispersion of Mo and S elements (Figure 2e).

Figure 2.

(a,b) TEM images of SQDs; (c) size distribution of SQDs; (d,e) TEM images and elemental mapping of MoS2/SQDs.

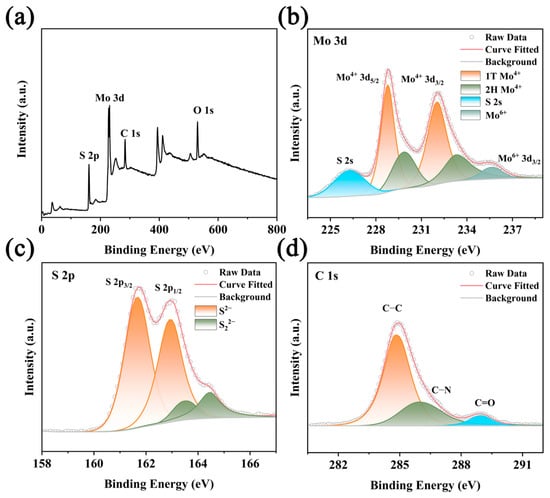

The surface composition and valence states of the synthesized MoS2/SQDs samples were determined using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). The XPS scans revealed the presence of sulfur (S), molybdenum (Mo), oxygen (O), and carbon (C) components in the samples (Figure 3a). The Mo 3d spectrum (Figure 3b) shows six prominent peaks: the peaks at 228.75 and 232.02 eV are identified as the Mo 3d3/2 of Mo4+, while the peaks at 229.86 and 233.33 eV correspond to the Mo 3d5/2 of Mo4+. The peak at a binding energy of 226.24 eV is attributed to S 2s, and the peak at a binding energy of approximately 235.5 eV is the Mo 3d3/2 peak of Mo6+, consistent with previous research findings [30]. From Figure 3c, it can be observed that there are two strong peaks located at 161.7 eV and 162.9 eV in the high-resolution spectra of S 2p1/2 and S 2p3/2, respectively, and the sulfur species exist in the form of S2− ions [31]. Based on the fitting results, the peak observed at 161.5 eV likely indicates the presence of sulfur ions in a condition of low coordination on the surface, while the peak at 163.1 eV is indicative of the molybdenum–sulfur bond in MoS2. The peaks observed at 284.8, 286.3, and 288.9 eV in the C 1s spectra (Figure 3d) correspond to the presence of C-C, C-N, and C=O bonds, respectively.

Figure 3.

XPS spectra of MoS2/SQDs. (a) Full spectrum; (b) Mo 3d; (c) S 2p; (d) C 1s.

2.2. Electrochemical Performance Analysis

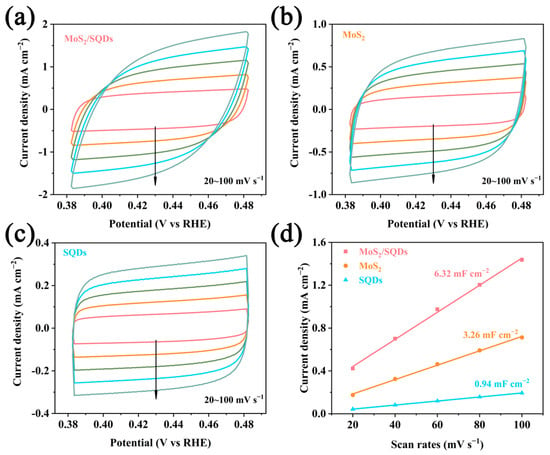

The number of active sites on the catalyst was assessed using double-layer capacitance analysis, while cyclic voltammetry was employed to analyze the electrochemical performance of the synthesized materials. Figure 4a–c depict the CV curves and the linear correlation between current density and scan rate at various scan rates. In comparison to other samples, MoS2/SQDs demonstrate a higher current density in the CV curves, suggesting a higher specific capacitance (Figure 4d). The obtained results indicate that the capacitance values of self-made MoS2 and MoS2/SQDs are 3.26 mF cm−2 and 6.32 mF cm−2, respectively. The charge carrier density of MoS2/SQDs is approximately double that of pure MoS2, indicating a greater number of active sites. This phenomenon can be attributed to the dispersion of previously clustered MoS2 nanosheets by SQDs, leading to a significant increase in the active surface area of MoS2 and consequently creating additional sites for chemical reactions, thereby enhancing overall reaction rates.

Figure 4.

The CV curves of MoS2/SQDs, MoS2, and SQDs are represented by (a), (b), and (c), respectively; (d) illustrates the capacitance double-layer diagram of MoS2/SQDs.

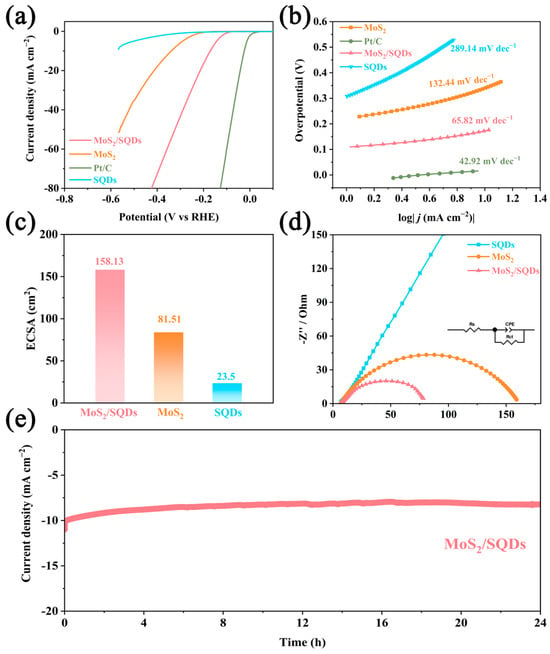

The electrochemical performance of the prepared samples for HER was evaluated in an acidic environment using a three-electrode electrochemical workstation, with a scan rate of 1 mV s−1. Figure 5a illustrates the linear sweep voltammetry profiles of commercially available 20% Pt/C, MoS2, SQDs, and MoS2/SQDs electrodes. While the Pt/C catalyst exhibits anticipated HER activity with an overpotential almost at zero, SQDs, however, perform poorly within the test potential range, suggesting minimal catalytic action for HER. Remarkably, MoS2/SQDs demonstrate stronger catalytic activity than pure molybdenum disulfide. The overpotential of MoS2 is 340 mV at a current density of 10 mA cm−2, much higher than that of MoS2/SQDs (204 mV). This suggests that MoS2 is the primary active component for HER, as indicated by the lower catalytic activity of SQDs. The combination of MoS2 and SQDs significantly enhances the catalytic performance of MoS2/SQDs in the HER process.

Figure 5.

The electrochemical characteristics of each sample were evaluated using the following methods: (a) linear scanning voltammetry; (b) Tafel curve analysis; (c) estimation of the electrochemical active area; (d) measurement of the electrochemical impedance spectra; (e) assessment of the stability of the MoS2/SQDs samples over a 24 h period.

To comprehend the HER mechanism, we determined Tafel slopes by fitting the linear portion of the Tafel plots. Figure 5b depicts that the Tafel slope of the MoS2/SQDs catalyst is 65.82 mV dec−1, lower than that of MoS2 (132.44 mV dec−1) and SQDs (289.14 mV dec−1), indicating higher HER rates and faster kinetics for the MoS2/SQDs catalyst. A Tafel slope value of 65.82 mV dec−1 suggests the occurrence of the Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism on MoS2/SQDs during the HER process, where the Heyrovsky step dictates the reaction rate. Combining SQDs with MoS2 improves the separation of water molecules in the Volmer step, leading to increased HER kinetics and faster rates of charge transfer.

The ECSA of catalysts is determined by estimating the catalyst’s electrochemical Cdl, measured using CV in the non-Faradaic zone with gradually increasing scan rates. Among the MoS2/SQDs, MoS2, and SQDs samples, the MoS2/SQDs sample exhibits the highest Cdl value at 6.32 mF cm−2. The ECSA of the MoS2/SQDs catalyst is the greatest among the prepared catalysts, calculated to be 158.13 cm2 (Figure 5c). In comparison, the ECSA values for pure MoS2 and SQDs are calculated to be 81.51 cm2 and 23.5 cm2, respectively.

Figure 5d illustrates the electrochemical impedance spectra of the materials. The Nyquist plot commonly uses the diameter of the semicircle to ascertain the charge transfer resistance. A reduced diameter corresponds to decreased charge transfer resistance and an accelerated charge transfer rate. The inclusion of SQDs decreases the electrical resistance of MoS2, as indicated by notably lower semicircle diameters observed in MoS2/SQDs compared to MoS2 and SQDs alone. This reduction in resistance is beneficial for lowering the resistance of the interface reaction and enhancing performance, facilitating quicker electron transfer between the catalyst and electrolyte, thereby increasing charge transport during the HER process.

Stability is a significant criterion for catalysts, in addition to their catalytic activity. To further examine the stability of MoS2/SQDs in the electrocatalytic HER, current–time curves under overpotential conditions were measured. As depicted in Figure 5e, the initial current density of the MoS2/SQDs catalyst decreased by a mere 17% following a 24 h testing period. The exceptional resistance of MoS2/SQDs to electrochemical degradation in acidic environments was confirmed through a 24 h endurance test. The decrease in current density could potentially be explained by gas desorption on the electrode surface or sluggish mass transport of the electrolyte. As shown in Figure 6, after 24 h of stability testing, there were no significant changes in the phase and morphology of MoS2/SQDs, and they remained essentially consistent before and after stability testing. The high stability of MoS2/SQDs throughout prolonged electrochemical processes is validated by these results. Table 1 below demonstrates the comparison of the performance of MoS2/SQDs with other HER electrocatalysts.

Figure 6.

SEM (a) and XRD (b) of MoS2/SQDs after 24 h electrochemical stability testing.

Table 1.

Comparison of MoS2/SQDs with other HER electrocatalysts.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

Sodium molybdate dihydrate, thioacetamide (TAA), sulfuric acid, sublimed sulfur, polyethylene glycol (PEG), sodium hydroxide, anhydrous ethanol, and Nafion (5 wt%) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and Pt/C (20 wt%) was purchased from Shanghai Hesen Electric Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All reagents are ready for use without any further treatment.

3.2. Preparation of SQDs

SQDs were synthesized using a hydrothermal method [40]. First, 1.6 g of S, 3 g of PEG, 4 g of NaOH, and 100 mL of deionized water were stirred at 90 °C for 10 h. After cooling to room temperature, impurities were removed using a 0.22 µm pore size membrane. Dialysis was performed, and the SQD solution was collected after the dialysis was complete.

3.3. Preparation of MoS2

Next, 0.3 g of Na2MoO4·2H2O and 0.28 g of C2H5NS were sequentially added to 25 mL of deionized water. After magnetic stirring for 30 min, the mixture was transferred to a 50 mL high-pressure reaction vessel and subjected to hydrothermal reaction at 200 °C for 18 h. After natural cooling to room temperature, repeated centrifugation with a mixture of deionized water and anhydrous ethanol was performed to remove other impurity ions. Finally, the product was freeze-dried to collect the final product.

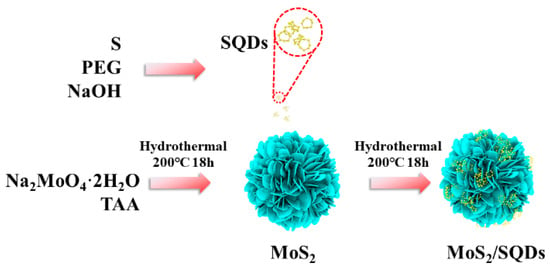

3.4. Preparation of MoS2/SQDs

As shown in Figure 7, MoS2/SQDs were synthesized via the hydrothermal method, using Na2MoO4·2H2O as the molybdenum source and C2H5NS as the sulfur source. Specifically, 0.3 g of Na2MoO4·2H2O and 0.28 g of C2H5NS were sequentially added to 30 mL of deionized water. After magnetic stirring for 20 min, 20 mL of SQD solution was added, followed by transfer to a 100 mL high-pressure reaction vessel for hydrothermal reaction at 200 °C for 18 h. After natural cooling to room temperature, repeated centrifugation with a mixture of deionized water and anhydrous ethanol was performed to remove other impurity ions. Finally, the product was freeze-dried to collect the final product.

Figure 7.

Preparation process scheme of MoS2/SQDs.

3.5. Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD; MiniFlex-600, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) with a CuKα source was used to analyze the crystalline condition of samples. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; K-Alpha, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to analyze the elemental valence of materials. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-2100, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used to test the grain size of the samples. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM; KYKY-EM 6900, KYKY Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was utilized to observe the morphology of the samples. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR; FTIR-2000, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) spectrometry was employed to analyze the structure of the samples.

3.6. Electrochemical Measurements

Herein, electrochemical measurements were performed in a 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte using a standard three-electrode system (CHI 760E Instruments, Chenhua, Shanghai, China) with a Ag/AgCl reference electrode (saturated with KCl) as a reference, graphite rod as a counter electrode, and GCE (3 mm, diam.) as a working electrode. Data were corrected to reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) without current and resistance (IR) modifications by employing the formula E(RHE) = E(Ag/AgCl) + 0.197 + 0.059pH. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was executed over 200 cycles using a scan rate of 50 mV s−1 within the non-Faraday reaction voltage range, resulting in the acquisition of consistent CV curves. The scanning range of electrochemical double layer capacitance (Cdl) was 0.15 to 0.25 V at various scanning rates (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 mV s−1). Linear scanning voltammetry (LSV) was conducted with a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 over a voltage window from −0.6 to 0.1 V. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted over a frequency interval from 0.01 Hz to 100 kHz with an amplitude of 5 mV. Electrochemical surface area (ECSA) was calculated based on CV curves using the formula ECSA = Cdl/Cs, with Cs denoting the specific capacitance from 0.02 to 0.06 mF cm−2. A mean value of 0.04 mF cm−2 was adopted in this study.

4. Conclusions

An introduction was provided on a hydrothermal approach for preparing catalysts such as SQDs, MoS2, and MoS2/SQDs. The characterization results of the synthesized materials were analyzed in detail using SEM, Raman, XRD, XPS, and TEM, confirming the successful synthesis of MoS2/SQD composite samples. Subsequently, the electrocatalytic activity of the MoS2/SQD composite material for the HER was investigated and compared to SQDs and self-synthesized MoS2. The results revealed the notably superior catalytic activity of the MoS2/SQDs composite catalyst compared to the aforementioned catalysts. The addition of SQDs significantly enhances the electrocatalytic performance of the MoS2 catalyst, as evidenced by the characterization results for morphology, surface characteristics, and valence states of the elements. Molybdenum disulfide has a greater specific surface area and more edges, attributed to the presence of SQDs, leading to an increased number of catalytic active sites for the HER process. The research findings suggest that MoS2/SQDs have a reduced Tafel slope of 62.85 mV dec−1 and a decreased overpotential of 204 mV at 10 mA cm−2. Besides its outstanding catalytic activity, the MoS2/SQDs catalyst also exhibits remarkable stability, with only a 17% reduction in initial current density after undergoing 24 h of timed current stability testing at 10 mA cm−2. This presents a novel methodology for creating high-efficiency catalysts for the HER.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.W.; methodology, T.T. and R.X.; software, Z.X. and S.D.; validation, J.W. and G.H.; formal analysis, M.L.; investigation, M.L. and L.J.; resources, M.L.; data curation, G.W.; writing—original draft preparation, G.W.; writing—review and editing, M.L., G.H. and J.W.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, M.L.; funding acquisition, M.L, L.J. and G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12164013), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (2020GXNSFBA297125), the Science and Technology Base and Talent Special Project of Guangxi Province (AD21220029), and the Research Foundation of Guilin University of Technology (GUTQDJJ2019011).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data can be made available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, H.L.; He, Q.; Zhang, Y.K.; Song, L. Structural self-reconstruction of catalysts in electrocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2968–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.M.; Diao, S.J.; Xu, R.Z.; Wei, G.Y.; Wen, J.F.; Hu, G.H.; Tang, T.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.Y.; Li, M.; et al. Construction of carboxylated-GO and MOFs composites for efficient removal of heavy metal ions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 636, 157827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seh, Z.W.; Kibsgaard, J.; Dickens, C.F.; Chorkendorff, I.B.; Norskov, J.K.; Jaramillo, T.F. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: Insights into materials design. Science 2017, 355, 6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.R.; Weng, S.T.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, Q.H.; Gu, L. Atomic-scale structural evolution of electrode materials in Li-ion batteries: A review. Rare Met. 2020, 39, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.Z.; Wei, G.Y.; Xie, Z.M.; Diao, S.J.; Wen, J.F.; Tang, T.; Jiang, L.; Li, M.; Hu, G.H. V2C MXene-modified g-C3N4 for enhanced visible-light photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 970, 172656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghafar, F.; Xu, X.; Jiang, S.P.; Shao, Z. Designing single-atom catalysts toward improved alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Rep. Energy 2022, 2, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.A.; Xu, X.M.; Kim, H.; Shao, Z.P.; Jung, W.C. Advanced electrocatalysts with unusual active sites for electrochemical water splitting. InfoMat 2024, 6, e12494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kong, B.; Zhao, D.Y.; Wang, H.T.; Selomulya, C. Strategies for developing transition metal phosphides as heterogeneous electrocatalysts for water splitting. Nano Today 2017, 15, 26–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.M.; Zhang, B. Recent advances in transition metal phosphide nanomaterials: Synthesis and applications in hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.X.; Zhang, Y. Noble metal-free hydrogen evolution catalysts for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5148–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, X.Y.; Eng, A.Y.S.; Ambrosi, A.; Tan, S.M.; Pumera, M. Electrochemistry of nanostructured layered transition-metal dichalcogenides. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11941–11966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, X.M.; Zhang, Y.L.; Han, Y.; Li, J.X.; Yang, L.; Benamara, M.; Chen, L.; Zhu, H.L. Two-dimensional water-coupled metallic MoS2 with nanochannels for ultrafast supercapacitors. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 1825–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.L.; Zhou, W.; Gao, R.; Yao, S.Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.Q.; Zheng, S.J.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, Q.L.; Li, Y.W.; et al. Low-temperature hydrogen production from water and methanol using Pt/α-MoC catalysts. Nature 2017, 544, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, W.Q.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.G.; Xu, S.M. Recovery and regeneration of Al2O3 with a high specific surface area from spent hydrodesulfurization catalyst CoMo/Al2O3. Rare Met. 2019, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.H.; Wang, J.G.; Zhang, Y.; Hua, W.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, H.Y. Ultrafast lithium energy storage enabled by interfacial construction of interlayer-expanded MoS2/N-doped carbon nanowires. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 13419–13427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, D.Q.; Ye, H.; Frey, N.C.; Kumar, H.; Lou, J.; Shenoy, V.B. Prediction of enhanced catalytic activity for hydrogen evolution reaction in janus transition metal dichalcogenides. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 3943–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.M.; Pan, Y.L.; Ge, L.; Chen, Y.B.; Mao, X.; Guan, D.Q.; Li, M.R.; Zhong, Y.J.; Hu, Z.W.; Peterson, V.K.; et al. High-performance perovskite composite electrocatalysts enabled by controllable interface engineering. Small 2021, 17, 2101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.P.; Yu, Y.F.; Ma, Q.L.; Chen, B.; Zhang, H. 2D transition-metal-dichalcogenide-nanosheet-based composites for photocatalytic and electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reactions. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kis, A.; Coleman, J.N.; Strano, M.S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splendiani, A.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.B.; Li, T.S.; Kim, J.; Chim, C.Y.; Galli, G.; Wang, F. Emerging photoluminescence in monolayer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y. Roadmap and direction toward high-performance MoS2 hydrogen evolution catalysts. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 11014–11039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.G.; Wang, H.L.; Xie, L.M.; Liang, Y.Y.; Hong, G.S.; Dai, H.J. MoS2 nanoparticles grown on graphene: An advanced catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7296–7299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Tsai, C.; Koh, A.L.; Cai, L.L.; Contryman, A.W.; Fragapane, A.H.; Zhao, J.H.; Han, H.S.; Manoharan, H.C.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; et al. Activating and optimizing MoS2 basal planes for hydrogen evolution through the formation of strained sulphur vacancies. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Li, H.B.; Xiao, J.P.; Tu, Y.C.; Deng, D.H.; Yang, H.X.; Tian, H.F.; Li, J.Q.; Ren, P.J.; Bao, X.H. Triggering the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity of the inert two-dimensional MoS2 surface via single-atom metal doping. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.W.; Shen, Z.H.; Zhu, C.; Li, J.C.; Ding, Z.Y.; Wang, P.; Pan, F.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Ma, H.X.; Wang, S.Y.; et al. Nitrogen-doped CoP electrocatalysts for coupled hydrogen evolution and sulfur generation with low energy consumption. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1800140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.Q.; Tao, X.; Qing, Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, F.; Luo, S.; Tian, C.H.; Liu, M.; Lu, X.H. Cr-doped FeNi-P nanoparticles encapsulated into N-doped carbon nanotube as a robust bifunctional catalyst for efficient overall water splitting. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1900178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.W.; Qin, Z.J.; McElhenny, B.; Zhang, F.H.; Chen, S.; Bao, J.M.; Wang, Z.M.M.; Song, H.Z.; Ren, Z.F. The effect of carbon quantum dots on the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction of manganese-nickel phosphide nanosheets. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 21488–21495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.W.; Wang, H.F.; Lin, Z.P.; Li, W.; Lin, B.; Qiu, W.Z.; Quan, Y.; Liu, Z.H.; Chen, S.G. In situ synthesis of edge-enriched MoS2 hierarchical nanorods with 1T/2H hybrid phases for highly efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. CrystEngComm 2019, 21, 1984–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.M.; Sun, W.W.; Wu, W.; Chen, B.; Al-Hilo, A.; Benamara, M.; Zhu, H.L.; Watanabe, F.; Cui, J.B.; Chen, T.P. Pure and stable metallic phase molybdenum disulfide nanosheets for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.X.; Rath, A.; Wang, H.Y.; Yu, S.H.; Pennycook, S.J.; Chua, D.H.C. Study of unique and highly crystalline MoS2/MoO2 nanostructures for electro chemical applications. Mater. Res. Lett. 2019, 7, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Jia, Z.J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Song, J.; Tian, L.L.; Qi, T. Carbon dots modified molybdenum disulfide as a high-efficiency hydrogen evolution electrocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 34898–34908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Z.; Du, L.X.; Shao, Y.B.; Wu, X.H. Silicon quantum dots-assistant synthesis of mesoporous MoS2 3D frameworks (SiQDs-MoS2) with 1T and 2H phases for hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Lett. 2019, 236, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Wang, X.F.; Tang, K.; Li, Q.; Sajjad, S.; Khan, S.; Farooqi, S.A.; Yan, C.L. SnS2 quantum dots growth on MoS2: Atomic-level heterostructure for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 300, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, P.S.; Kannan, N.; Babu, M.G.; Paulraj, G.; Jeganathan, K. Transition metal doped MoS2 nanosheets for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 37256–37263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.V.; Tekalgne, M.; Nguyen, T.P.; Wang, W.M.; Hong, S.H.; Cho, J.H.; Le, Q.; Jang, H.W.; Ahn, S.H.; Kim, S.Y. Control of the morphologies of molybdenum disulfide for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 11479–11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumesh, C.K. Zinc oxide functionalized molybdenum disulfide heterostructures as efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, D.R.; Xu, W.X.; Wang, C.; Wang, F.B.; Xu, J.J.; Xia, X.H.; Chen, H.Y. Energy level engineering of MoS2 by transition-metal doping for accelerating hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15479–15485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Ma, Q.; Ding, S.Y.; Zhao, Y.Z.; Song, W.Q.; Ren, H.P.; Song, X.Z.; Miao, Z.C. A molybdenum disulfide and 2D metal-organic framework nanocomposite for improved electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Lett. 2019, 239, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.L.; Ding, T.; Wang, C.D.; Yang, Q. 3D architecture constructed via the confined growth of MoS2 nanosheets in nanoporous carbon derived from metal-organic frameworks for efficient hydrogen production. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 18004–18009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Shan, C.F.; Wei, G.Y.; Wen, J.F.; Jiang, L.; Hu, G.H.; Fang, Z.J.; Tang, T.; Li, M. A novel non-metallic photocatalyst: Phosphorus-doped sulfur quantum dots. Molecules 2023, 28, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).