Abstract

Natural products and plant extracts exhibit many biological activities, including that related to the defense mechanisms against parasites. Many studies have investigated the biological functions of secondary metabolites and reported evidence of antiviral activities. The pandemic emergencies have further increased the interest in finding antiviral agents, and efforts are oriented to investigate possible activities of secondary plant metabolites against human viruses and their potential application in treating or preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection. In this review, we performed a comprehensive analysis of studies through in silico and in vitro investigations, also including in vivo applications and clinical trials, to evaluate the state of knowledge on the antiviral activities of secondary metabolites against human viruses and their potential application in treating or preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a particular focus on natural compounds present in food plants. Although some of the food plant secondary metabolites seem to be useful in the prevention and as a possible therapeutic management against SARS-CoV-2, up to now, no molecules can be used as a potential treatment for COVID-19; however, more research is needed.

1. Introduction

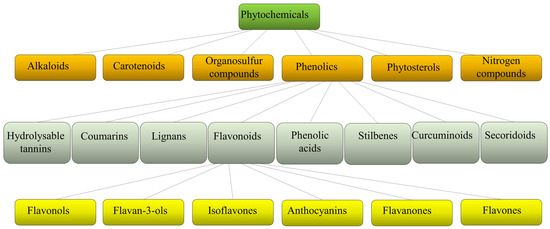

Plants produce a variety of structurally diverse and often complex secondary metabolites (SM) with a range of biological functions [1]. Plant SM can be classified according to several criteria, such as chemical structure (presence of rings or sugars), composition (containing nitrogen or not), solubility in organic solvents or water, and the biosynthetic pathway [2]. They include alkaloids, carotenoids, organosulfur compounds, phytosterols, nitrogen compounds, and phenolics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic classification of phytochemicals, with sub-classification of phenolics and flavonoids.

Each class is then divided into further classes. In particular, phenolics comprise a large group of different compounds, with the phenolic hydroxyl groups being the common structural feature. These are usually found conjugated with sugars and organic acids and can be divided into seven main classes such as hydrolyzable tannins, coumarins, lignans, phenolic acids, stilbenes, curcuminoids, and flavonoids [3] (Figure 1). Flavonoids exist broadly in nature, and to date, more than 9000 flavonoids have been reported. They can be divided into the following subclasses: flavonols, flavan-3-ols, isoflavones, anthocyanins, flavanones, and flavones. Flavonoids share a common structure of two benzene rings connected by three carbon atoms forming an oxygenated heterocycle and are responsible for the red, blue, and yellow coloration of plants and are found in foods and beverages of plant origin, such as fruits, vegetables, tea, cocoa, and wine [4,5]. Recent studies have reported that some of these natural compounds can reduce the risk of many chronic diseases and can significantly modulate and diversify the composition of the human gut microbiome [6]. Consumption of phenolic compounds can help to prevent metabolic, cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, and cancerous diseases [7,8] due to their high antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory immunomodulatory activities [9,10,11]. Eating plant-based foods is part of many diverse dietary patterns, including the well-studied Mediterranean diet [12], vegan, and vegetarian approaches. Despite the widely known health benefits of consuming fruits and vegetables, the intake is often inadequate and a large number of adults worldwide do not consume the daily-recommended servings. So, in the attempt to improve health, dietary guidelines and health promotion campaigns have advocated for individuals to “eat a rainbow” of fruit and vegetables, i.e., to take a qualitative color rather than a quantitative servings approach, based on the association of each color with a health benefit. For example, red foods include antioxidants that can contribute to decreased inflammation in the body; orange foods are abundant in carotenoids and have been linked to endocrine-regulating activities; yellow foods have been found to aid in digestion due to their fiber content and bioflavonoids that promote healthy gut bacteria; green foods, especially green leafy vegetables, contain an abundance of polyphenols that aid in reducing cardiovascular risk factors such as high blood pressure; blue or purple foods have been found to improve memory and mood because of flavonoids, flavonols, and phenolic acids that promote cognitive functions.

Recent technological advances in analytical methods such as metabolomics, metabolic engineering, and synthetic biology, as well as the ad hoc designed computational tools and databases, are providing powerful tools for drug discovery based on natural compounds [6]. It has been known that natural products and plant extracts exhibit potent anti-viral activities, often against multiple virus families, thus suggesting that they may be useful as broad-spectrum antiviral agents [13,14].

The COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has prompted researchers to conduct many studies aimed at identifying useful compounds to counter the viral agent. As reported by the World Health Organization’s weekly epidemiological update dated 22 February 2023, “over 757 million confirmed cases and over 6.8 million deaths have been reported globally” [15], with nearly 5.3 million new cases and over 48,000 deaths in the 4 weeks preceding the report. For a state-of-the-art review of the pandemic two years after its appearance and the related lessons learned, an interesting article was published in September 2022 [16].

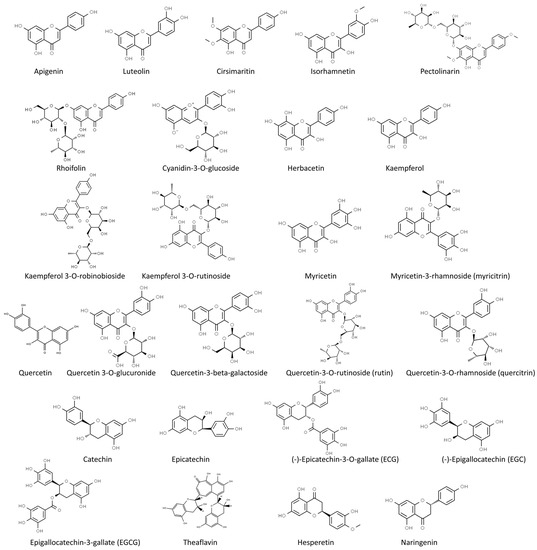

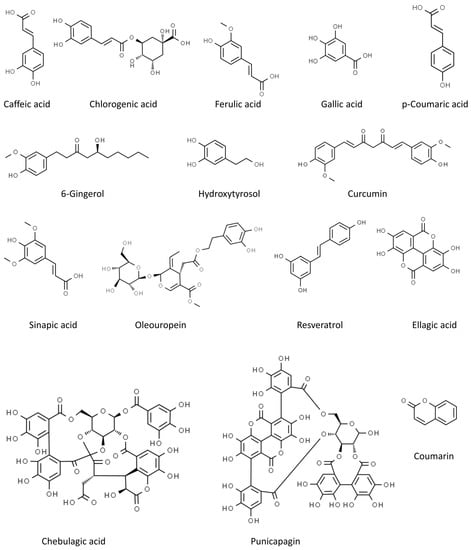

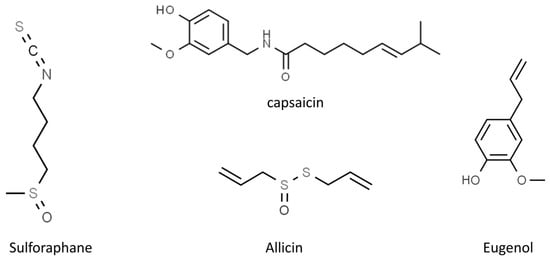

In our review, we summarize the progress of studies on the antiviral activities of secondary metabolites and, in particular, we focus on 45 widely studied natural compounds present in food plants selected from the literature on the basis of their activity against human viruses and their potential application in treating or preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection, as demonstrated through in silico and in vitro studies, including also any in vivo application. The list of 45 phytochemicals and their related food source is shown in Table 1. Their chemical structures are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Table 1.

List of selected compounds and their anti-viral properties against various viruses and/or SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of the selected flavonoids (from ChemSpider, http://www.chemspider.com/ accessed on 24 February 2023).

Figure 3.

Chemical structure of the other selected phenolics (from ChemSpider, http://www.chemspider.com/ accessed on 24 February 2023).

Figure 4.

Chemical structure of the other selected phytochemicals (from ChemSpider, http://www.chemspider.com/ accessed on 24 February 2023).

6. In Vivo Studies and Clinical Trials

Until now, to the best of our knowledge, there have been few in vivo studies to evaluate the antiviral activity of natural products or phytochemicals in SARS-CoV-2-infected animal models, especially for the molecules covered in this review. For example, in the aforementioned study by Ordonez et al. [125], the researchers conducted studies in a mouse model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and found that the pre-treatment with sulforaphane resulted in a statistically significant decrease in both the viral load or amount of virus, in the lungs and upper respiratory tract as well as the amount of lung injury compared with infected mice that were not given sulforaphane. Moreover, sulforaphane also decreases inflammation in the lungs, protecting the cells from a hyperactive immune response. Furthermore, in the study of Paidi et al. [131], it has been demonstrated that oral treatment with eugenol reduced lung inflammation, decreased fever, improved heart function, decreased serum markers, and enhanced locomotor activities in SARS-CoV-2 spike S1-intoxicated mice. Anyway, further and more specific experimental and preclinical studies on the effects of these compounds in SARS-CoV-2-infected animal models have to be performed.

Numerous studies have been performed since the beginning of the pandemic to introduce plant extracts and phytochemicals effective in the management of SARS-CoV-2, also in combination with traditional medicines. As an example, in an empirical study conducted at a Wuhan hospital, patients were treated with traditional Chinese medicine remedies, including herbs with a high quercetin content, in addition to conventional therapies. The clinical results showed that patients with coronavirus pneumonia enhanced their immune ability against SARS-CoV-2 with a decrease in hospitalization days [148]. One of the main problems with the use of natural compounds in the treatment of diseases is their low solubility and bioavailability, which makes clinical studies difficult and problematic. Among the ways used to improve drug delivery, biodistribution, biodegradability, and bioavailability of plant-based secondary metabolites, encapsulation or conjugation of these compounds with nanocarriers can be a useful solution. Generally, the most used nanocarriers are organic-based and are basically composed of lipids such as micelles, liposomes, niosomes, bilosomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, and archaeosomes, and these lipid-based drug delivery systems are used to deliver hydrophobic drugs in the body [149].

There are numerous clinical trials investigating the effects of phytochemicals in prophylaxis and the treatment of COVID-19 in which phytochemicals are assessed as pure compounds, pure compounds in combination with other natural bioactive compounds and/or drugs or polyphenol-rich extracts. A list of ongoing or completed clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of some of the compounds covered by this review in the prevention and as a possible therapeutic management against COVID-19 and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (accessed on 27 February 2023) is given in Supplementary Table S1.

For example, Di Pierro et al. carried out two different clinical trials to demonstrate the effectiveness of quercetin, especially in the early stages of COVID-19 infection. In particular, in the first trial, supplementation with two doses of 200 mg quercetin daily for 30 days administered to 76 outpatients reduced the number of patients hospitalized (9.2 vs. 28.9%), the days of hospitalization (1.6 vs. 6.8 days), the need for oxygen therapy (1.3 vs. 19.7%) and the aggravation of symptoms compared to the control group [150]. In the second trial, 42 COVID-19 symptom outpatients were divided into two groups, one group receiving standard care treatment while the other group receiving quercetin as a supplemental treatment. Quercetin supplementation not only shortened the timing of molecular test conversion from positive to negative but also reduced the severity of symptoms of COVID-19 [151]. Similarly, in another trial, 120 outpatients received two doses of 250 mg quercetin daily for three months and, also in this case, the number of patients hospitalized (1.67 vs. 6.67%) was lower than in the control group [152]. In a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled proof-of-concept trial of resveratrol for outpatient treatment of mild COVID-19, McCreary et al. administered placebo or resveratrol to 105 participants and found that resveratrol recipients had a lower incidence compared to placebo of hospitalization, COVID-19 related Accident and Emergency (A&E) visits and pneumonia [153].

Many clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of phytochemicals in the prevention and/or treatment of COVID-19 and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov whose results, however, to the best of our knowledge, have not yet been published. For example, a clinical trial has been conducted on 524 volunteer healthcare worker participants with the purpose of determining the efficacy of Previfenon® (epigallocatechin-3-gallate-EGCG) in preventing COVID-19, enhancing systemic immunity, and reducing the frequency and intensity of specific symptoms when used as pre-exposure chemoprophylaxis to SARS-CoV-2. To the best of our knowledge, the stage of this study is still phase 3 [Clinicaltrials.gov I.D. NCT04446065; accessed on 27 February 2023].

A double-blind, placebo-controlled study was carried out in Iran on 40 COVID-19 patients with the aim to identify the effects of nano-curcumin, i.e., curcumin formulated with the aid of nanotechnology in nano-micelles to improve its stability and solubility, on the modulation of inflammatory cytokines, the secretion of which increases significantly in COVID-19 patients. Results demonstrated that nano-curcumin was able to modulate the increased rate of inflammatory cytokines, especially IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA expression [154]. The efficacy of nano-curcumin in the management of 21 mild-to-moderate hospitalized COVID-19 patients was also tested in an open, non-randomized clinical trial. Results demonstrated that most of the symptoms, including fever and chills, tachypnoea, myalgia, and cough, resolved significantly faster in the curcumin group than in the control ones. Moreover, the duration of supplemental O2 use and hospitalization was also meaningfully shorter in the treatment group [155]. Nano-curcumin formulation was also administered to mild to moderate COVID-19 patients in the outpatient setting in a randomized triple-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to assess the efficacy in the management of the symptoms. The reported results demonstrated that the nanoformulation of curcumin with a dose of 80 mg twice daily could fasten the resolution time of COVID-19-induced symptoms, particularly cough, taste and smell disturbances, chills, and increment of lymphocyte count in comparison with placebo. No substantial adverse reaction was reported in the treatment group [156]. Both of these last two clinical trials have been registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials with the ID IRCT20200408046990N1. [https://www.irct.ir/trial/47061; accessed on 27 February 2023].

7. Conclusions

The rush to publication has not always disseminated results of verified quality, and they should be considered very carefully. For some compounds object of this review, in vitro assays have demonstrated antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2, also supported by in silico hypotheses on the mechanism of action. Anyway, phenolics consumption helps to modulate the immune system through several mechanisms of action, which significantly influences the prevention of SARS-CoV-2. Clinical trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of SM in the prevention and as a possible therapeutic management against SARS-CoV-2; however, more research is needed. As an example, derivative or chemical modifications of secondary metabolites could be explored as promising compounds.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules28062470/s1, Table S1: Clinical trials investigating the effects of selected phytochemicals in prophylaxis and/or the treatment of SARS-CoV-2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C. and A.F.; methodology, V.C., D.G. and A.F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.C.; writing—review and editing, D.G. and A.F.; visualization, V.C. and D.G.; supervision, V.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

D.G. was supported within the framework of “CIR01_00017—“CNRBiOmics—Centro Nazionale di Ricerca in Bioinformatica per le Scienze Omiche”—Rafforzamento del capitale umano”—CUP B56J20000960001. The activities of the authors are within the framework of: PON R&I 2014-2020 PIR01_00017 CNRbiomics Project; CNR Project NUTRAGE; CNR Project ALIFUN (PON MUR 2018).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Garagounis, C.; Delkis, N.; Papadopoulou, K.K. Unraveling the roles of plant specialized metabolites: Using synthetic biology to design molecular biosensors. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 1338–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weremczuk-Jeżyna, I.; Hnatuszko-Konka, K.; Lebelt, L.; Grzegorczyk-Karolak, I. The Protective Function and Modification of Secondary Metabolite Accumulation in Response to Light Stress in Dracocephalum forrestii Shoots. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.H. Health bene fits of phytochemicals in whole foods. In Nutritional Health: Strategies for Disease Prevention, 3rd ed.; Temple, N.J., Wilson, T., Jacobs, D.R., Jr., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Baker, D.H. An ethnopharmacological review on the therapeutical properties of fla-vonoids and their mechanisms of actions: A comprehensive review based on up to date knowledge. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 445–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periwal, V.; Bassler, S.; Andrejev, S.; Gabrielli, N.; Patil, K.R.; Typas, A.; Patil, K.R. Bioactivity assessment of natural compounds using machine learning models trained on target similarity between drugs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Rocchetti, G.; Chadha, S.; Zengin, G.; Bungau, S.; Kumar, A.; Mehta, V.; Uddin, M.S.; Khullar, G.; Setia, D.; et al. Phytochemicals from Plant Foods as Potential Source of Antiviral Agents: An Overview. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Kulieva, V.; Atoche-Dioses, S.; Hernandez-Martínez, E. Phenolic compounds of mango (Mangifera indica) by-products: Antioxidant and antimicrobial potential, use in disease prevention and food industry, methods of extraction and microencapsulation. Sci. Agropecu. 2021, 12, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Kulieva, V.A.; Gutierrez-Valverde, K.S.; Villegas-Yarleque, M.; Camacho-Orbegoso, E.W.; Villegas-Aguilar, G.F. Research trends on mango by-products: A literature review with bibliometric analysis. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 2760–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Andrés-Juan, C.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. Impact of Zinc, Glutathione, and Polyphenols as Antioxidants in the Immune Response against SARS-CoV-2. Processes 2021, 9, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehany, T.; Khalifa, I.; Barakat, H.; Althwab, S.A.; Alharbi, Y.M.; El-Sohaimy, S. Polyphenols as promising biologically active substances for preventing SARS-CoV-2: A review with research evidence and underlying mechanisms. Food Biosci. 2021, 40, 100891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; A Literature Review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, S.A.M.; Yosri, N.; El-Mallah, M.F.; Ghonaim, R.; Guo, Z.; Musharraf, S.G.; Du, M.; Khatib, A.; Xiao, J.; Saeed, A.; et al. Screening for natural and derived bio-active compounds in preclinical and clinical studies: One of the frontlines of fighting the coronaviruses pandemic. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosri, N.; Abd El-Wahed, A.A.; Ghonaim, R.; Khattab, O.M.; Sabry, A.; Ibrahim, M.A.A.; Moustafa, M.F.; Guo, Z.; Zou, X.; Algethami, A.F.M.; et al. Anti-Viral and Immunomodulatory Properties of Propolis: Chemical Diversity, Pharmacological Properties, Preclinical and Clinical Applications, and In Silico Potential against SARS-CoV-2. Foods 2021, 10, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Weekly Epidemiological Update on COVID-19–22 February 2023, Edition 131, 22 February 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- da Silva, S.J.R.; do Nascimento, J.C.F.; Germano Mendes, R.P.; Guarines, K.M.; Targino Alves da Silva, C.; da Silva, P.G.; de Magalhães, J.J.F.; Vigar, J.R.J.; Silva-Júnior, A.; Kohl, A.; et al. Two Years into the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learned. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 1758–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K.; Tsujimoto, K.; Uozaki, M.; Nishide, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Koyama, A.H.; Yamasaki, H. Inhibition of multiplication of herpes simplex virus by caffeic acid. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 28, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, L.C.; Chiang, W.; Chang, M.Y.; Ng, L.T.; Lin, C.C. Antiviral activity of Plantago major extracts and related compounds in vitro. Antivir. Res. 2002, 55, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, G.; Zuo, J. Caffeic acid inhibits HCV replication via induction of IFNα antiviral response through p62-mediated Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Antivir. Res. 2018, 154, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utsunomiya, H.; Ichinose, M.; Ikeda, K.; Uozaki, M.; Morishita, J.; Kuwahara, T.; Koyama, A.H.; Yamasaki, H. Inhibition by caffeic acid of the influenza A virus multiplication in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.R.; Lin, C.S.; Lai, H.C.; Lin, Y.P.; Wang, C.Y.; Tsai, Y.C.; Wu, K.C.; Huang, S.H.; Lin, C.W. Antiviral activity of Sambucus FormosanaNakai ethanol extract and related phenolic acid constituents against human coronavirus NL63. Virus Res. 2019, 273, 197767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, D.; Nandi, R.; Jagadeesan, R.; Kumar, N.; Prakash, A.; Kumar, D. Identification of potential inhibitors against SARS-CoV-2 by targeting proteins responsible for envelope formation and virion assembly using docking based virtual screening, and pharmacokinetics approaches. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 84, 104451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.S.; Khatib, N.A.; Patil, V.S.; Suryawanshi, S.S. Chlorogenic acid may be a potent inhibitor of dimeric SARS-CoV-2 main protease 3CLpro: An in silico study. Tradit. Med. Res. 2021, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gizawy, H.A.; Boshra, S.A.; Mostafa, A.; Mahmoud, S.H.; Ismail, M.I.; Alsfouk, A.A.; Taher, A.T.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Pimenta dioica (L.) Merr. Bioactive Constituents Exert Anti-SARS-CoV-2 and Anti-Inflammatory Activities: Molecular Docking and Dynamics, In vitro, and In Vivo Studies. Molecules 2021, 26, 5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, W.-C.; Chang, S.-P.; Lin, L.-C.; Li, C.-L.; Richardson, C.D.; Lin, C.-C.; Lin, L.-T. Limonium Sinense and gallic acid suppress hepatitis C virus infection by blocking early viral entry. Antivir. Res. 2015, 118, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutan, M.M.; Goel, T.; Das, T.; Malik, S.; Suri, S.; Rawat, A.K.; Srivastava, S.K.; Tuli, R.; Malhotra, S.; Gupta, S.K. Ellagic acid & gallic acid from Lagerstroemia speciosa L. inhibit HIV-1 infection through inhibition of HIV-1 protease & reverse transcriptase activity. Ind. J. Med. Res. 2013, 137, 540–548. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.J.; Song, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Baek, S.H. In vitro anti-enterovirus 71 activity of gallic acid from Woodfordia fruticosa flowers. Lett. Appl. Microb. 2010, 50, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Oh, M.; Seok, J.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, D.B.; Bae, G.; Bae, H.I.; Bae, S.Y.; Hong, Y.M.; Kwon, S.O.; et al. Antiviral Effects of Black Raspberry (Rubus coreanus) Seed and Its Gallic Acid against Influenza Virus Infection. Viruses 2016, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treml, J.; Gazdová, M.; Šmejkal, K.; Šudomová, M.; Kubatka, P.; Hassan, S.T.S. Natural products-derived chemicals: Breaking barriers to novel anti-HSV drug development. Viruses 2020, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrasheid, A.A.; Babiker, M.Y.; Awad, T.A. Evaluation of certain medicinal plants compounds as new potential inhibitors of novel corona virus (COVID-19) using molecular docking analysis. In silico. Pharmacology 2021, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.J.; Shin, H.M.; Perumalsamy, H.; Wang, X.; Ahn, Y.-J. Antiviral effects and possible mechanisms of action of constituents from Brazilian propolis and related compounds. J. Apic. Res. 2019, 59, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaldam, M.A.; Yahya, G.; Mohamed, N.H.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Al Naggar, Y. In silico Screening of Potent Bioactive Compounds from Honey Bee Products Against COVID-19 Target Enzymes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 40507–40514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfali, R.; Rateb, M.E.; Hassan, H.M.; Alonazi, M.; Gomaa, M.R.; Mahrous, N.; GabAllah, M.; Kandeil, A.; Perveen, S.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; et al. Sinapic Acid Suppresses SARS-CoV-2 Replication by Targeting Its Envelope Protein. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelli, M.; Kiani, A.K.; Paolacci, S.; Manara, E.; Kurti, D.; Dhuli, K.; Bushati, V.; Miertus, J.; Pangallo, D.; Baglivo, M.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol: A natural compound with promising pharmacological activities. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 309, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Ogawa, H.; Hara, A.; Yoshida, Y.; Yonezawa, Y.; Karibe, K.; Nghia, V.B.; Yoshimura, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamada, M.; et al. Mechanism of the antiviral effect of hydroxytyrosol on influenza virus appears to involve morphological change of the virus. Antivir. Res. 2009, 83, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolacci, S.; Kiani, A.K.; Shree, P.; Tripathi, D.; Tripathi, Y.B.; Tripathi, P.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Farronato, M.; Farronato, G.; Connelly, S.T.; et al. Scoping review on the role and interactions of hydroxytyrosol and alpha-cyclodextrin in lipid-raft-mediated endocytosis of SARS-CoV-2 and bioinformatic molecular docking studies. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25 (Suppl. 1), 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crudele, A.; Smeriglio, A.; Ingegneri, M.; Panera, N.; Bianchi, M.; Braghini, M.R.; Pastore, A.; Tocco, V.; Carsetti, R.; Zaffina, S.; et al. Hydroxytyrosol Recovers SARS-CoV-2-PLpro-Dependent Impairment of Interferon Related Genes in Polarized Human Airway, Intestinal and Liver Epithelial Cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Song, J.; Liu, A.; Xiao, B.; Li, S.; Wen, Z.; Lu, Y.; Du, G. Research Progress of the Antiviral Bioactivities of Natural Flavonoids. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2020, 10, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Rane, J.S.; Chatterjee, A.; Kumar, A.; Khan, R.; Prakash, A.; Ray, S. Targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein of COVID-19 with naturally occurring phytochemicals: An in silico study for drug development. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, S.; Hira, S.; Al-sehemi, A.G.; Abdullah, H.; Khan, M.; Irfan, M.; Iqbal, J. Exploring the new potential antiviral constituents of Moringa oliefera for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis: An in silico molecular docking and dynamic studies. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2021, 767, 138379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotuyi, I.O.; Nash, O.; Ajiboye, B.O.; Olumekun, V.O.; Oyinloye, B.E.; Olonisakin, A.; Ajayi, A.O.; Olusanya, O.; Akomolafe, F.S.; Adelakun, N. Aframomum melegueta secondary metabolites exhibit polypharmacology against SARS-CoV-2 drug targets: In vitro validation of furin inhibition. Phyther. Res. 2020, 35, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariono, M.; Hariyono, P.; Dwiastuti, R.; Setyani, W.; Yusuf, M.; Salin, N.; Wahab, H. Potential SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors from chromene, flavonoid and hydroxamic acid compound based on fret assay, docking and pharmacophore studies. Res. Chem. 2021, 3, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, D.; Das, R.; Sobia, P.; Dwivedi, V.; Ghosh, S.; Samanta, A.; Chattopadhyay, D. Pedilanthus tithymaloides Inhibits HSV infection by modulating NF-κB signaling. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.C.; Kumari, R.; Yadav, S.; Yadav, J.P. Antiviral potential of phytoligands against chymotrypsin-like protease of COVID-19 virus using molecular docking studies: An optimistic approach. Res. Square, 2020; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakshit, G.; Dagur, P.; Satpathy, S.; Patra, A.; Jain, A.; Ghosh, M. Flavonoids as potential therapeutics against novel coronavirus disease-2019 (nCOVID-19). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 6989–7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munafò, F.; Donati, E.; Brindani, N.; Ottonello, G.; Armirotti, A.; De Vivo, M. Quercetin and luteolin are single-digit micromolar inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Kim, S.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, M.S. Inhibition of SARSCoV 3CL protease by flavonoids. J. Enzyme. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020, 35, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallei, T.E.; Tumilaar, S.G.; Niode, N.J.; Fatimawali, F.; Kepel, B.J.; Idroes, R.; Effendi, Y.; Sakib, S.A.; Emran, T.B. Potential of Plant Bioactive Compounds as SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) and Spike (S) Glycoprotein Inhibitors: A Molecular Docking Study. Scientifica 2020, 2020, 6307457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Shin, D.H. Flavonoids with inhibitory activity against SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2020, 35, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Wang, H.; Ma, L.; Ma, X.; Yin, J.; Wu, S.; Huang, H.; Li, Y. Cirsimaritin inhibits influenza A virus replication by downregulating the NF-κB signal transduction pathway. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiou, O.; Bouziane, I.; Frissou, N.; Bouslama, Z.; Honcharova, O.; Djemel, A.; Benselhoub, A. In-Silico Identification of Potent Inhibitors of COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro) from Natural Products. Int. J. Biochem. Physiol. 2020, 5, 16000189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitsillou, E.; Liang, J.; Ververis, K.; Lim, K.W.; Hung, A.; Karagiannis, T.C. Identification of Small Molecule Inhibitors of the Deubiquitinating Activity of the SARS-CoV-2 Papain-Like Protease: In silico Molecular Docking Studies and in vitro Enzymatic Activity Assay. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 623971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayem, A.A.; Choi, H.Y.; Kim, Y.B.; Cho, S.-G. Antiviral Effect of Methylated Flavonol Isorhamnetin against Influenza. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicidomini, C.; Roviello, V.; Roviello, G.N. In silico Investigation on the Interaction of Chiral Phytochemicals from Opuntia ficus-indica with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Ta, W.; Tang, W.; Hua, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Lu, W. Potential antiviral activity of isorhamnetin against SARS-CoV-2 spike pseudotyped virus in vitro. Drug Dev. Res. 2021, 82, 1124–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Heng, W.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Wei, X.; Peng, S.; Saleem, S.; Khan, M.; Ali, S.S.; Wei, D.Q. In silico and in vitro evaluation of kaempferol as a potential inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (3CLpro). Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 2841–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaerunnisa, S.; Kurniawan, H.; Awaluddin, R.; Suhartati, S.; Soetjipto, S. Potential Inhibitor of COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro) From Several Medicinal Plant Compounds by Molecular Docking Study. Preprints 2020, 2020030226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilginer, S.; Gözcü, S.; Güvenalp, Z. Molecular Docking Study of Several Seconder Metabolites from Medicinal Plants as Potential Inhibitors of COVID-19 Main Protease. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 19, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, A.K.; Jaiswal, S.; Sharma, N.; Borah, S.; Kaur, G. Flavan-based phytoconstituents inhibit Mpro, a SARS-COV-2 molecular target, in silico. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 11545–11559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmolinsky, L.; Huleihel, M.; Zaccai, M.; Ben-Shabat, S. Potent antiviral flavone glycosides from Ficus benjamina leaves. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owis, A.I.; El-Hawary, M.S.; El Amir, D.; Aly, O.M.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Kamel, M.S. Molecular docking reveals the potential of Salvadora persica flavonoids to inhibit COVID-19 virus main protease. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 19570–19575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daino, G.L.; Frau, A.; Sanna, C.; Rigano, D.; Distinto, S.; Madau, V.; Esposito, F.; Fanunza, E.; Bianco, G.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; et al. Identification of Myricetin as an Ebola virus VP35-double-stranded RNA interaction inhibitor through a novel fluorescence-based assay. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 6367–6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, H.; Huang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, J. Multiple modes of action of myricetin in influenza A virus infection. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 2797–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, Y.; Chin, Y.W.; Jee, J.G.; Keum, Y.S.; Jeong, Y.J. Identification of myricetin and scutellarein as novel chemical inhibitors of the SARS coronavirus helicase, nsP13. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4049–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrak, S.A.; Merzouk, H.; Mokhtari-Soulimane, N. Potential bioactive glycosylated flavonoids as SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors: A molecular docking and simulation studies. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, T.; Cui, M.; Zheng, C.; Wang, M.; Sun, R.; Gao, D.; Bao, J.; Ren, S.; Yang, B.; Lin, J.; et al. Myricetin Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Viral Replication by Targeting Mpro and Ameliorates Pulmonary Inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 669642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Ye, F.; Sun, Q.; Liang, H.; Li, C.; Li, S.; Lu, R.; Huang, B.; Tan, W.; Lai, L. Scutellaria baicalensis extract and baicalein inhibit replication of SARS-CoV-2 and its 3C-like protease in vitro. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, J.T.; Suárez, A.I.; Serrano, M.L.; Baptista, J.; Pujol, F.H.; Rangel, H.R. The role of the glycosyl moiety of myricetin derivatives in anti-HIV-1 activity in vitro. AIDS Res. Ther. 2017, 14, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, R.S.; Jagdale, S.S.; Bansode, S.B.; Shiva Shankar, S.; Tellis, M.B.; Pandya, V.K.; Chugh, A.; Giri, A.P.; Kulkarni, M.J. Discovery of potential multi-target-directed ligands by targeting host-specific SARS-CoV-2 structurally conserved main protease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 39, 3099–3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lulu, S.S.; Thabitha, A.; Vino, S.; Priya, A.M.; Rout, M. Naringenin and quercetin—Potential anti-HCV agents for NS2 protease targets. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, H.H.; Shin, Y.S.; Kang, H.; Cho, H. The anti-HSV-1 effect of quercetin is dependent on the suppression of TLR-3 in Raw 264.7 cells. Arch. Pharmacal. Res. 2017, 40, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, R.; Bhattacharya, K.; Ali, A.; Sandilya, S. Quercitin as an antiviral weapon-A review. J. Appl. Pharm. Res. 2021, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, R.; Li, X.; He, J.; Jiang, S.; Liu, S.; Yang, J. Quercetin as an antiviral agent inhibits influenza A virus (IAV) entry. Viruses 2015, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abian, O.; Ortega-Alarcon, D.; Jimenez-Alesanco, A.; Ceballos-Laita, L.; Vega, S.; Reyburn, H.T.; Rizzuti, B.; Velazquez-Campoy, A. Structural stability of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and identification of quercetin as an inhibitor by experimental screening. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1693–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Raghuvanshi, R.; Ceylan, F.D.; Bolling, B.W. Quercetin and Its Metabolites Inhibit Recombinant Human AngiotensinConverting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13982–13989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Luo, C.; Liu, H.; Xu, W.; Chen, G.; Liew, O.W.; Zhu, W.; Puah, C.M.; Shen, X.; et al. Binding interaction of quercetin-3-β-galactoside and its synthetic derivatives with SARS-CoV 3CLpro: Structure-activity relationship studies reveal salient pharmacophore features. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 8295–8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, M.; Kamra, M.; Mullick, R.; Bhattacharya, S.; Das, S.; Karande, A.A. Identification of a flavonoid isolated from plum (Prunus domestica) as a potent inhibitor of Hepatitis C virus entry. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.J.; Song, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Kwon, D.H. Inhibitory effects of quercetin 3-rhamnoside on influenza A virus replication. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 37, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frengki, F.; Putra, D.P.; Wahyuni, F.S.; Khambri, D.; Vanda, H.; Sofia, V. Potential antiviral of catechins and their derivatives to inhibit sars-cov-2 receptors of Mpro protein and spike glycoprotein in COVID-19 through the in silico approach. J. Kedokt. Hewan 2020, 14, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Chakraborty, A.; Biswas, A.; Chowdhuri, S. Evaluation of green tea polyphenols as novel corona virus (SARS-CoV-2) main protease (Mpro) inhibitors—An in silico docking and molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 4362–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Pal, U.; Paladhi, P.; Dutta, S.; Paul, P.; Pal, S.; Das, D.; Ganguly, A.; Dutta, I.; Mandal, S.; et al. Evaluation of potency of the selected bioactive molecules from Indian medicinal plants with MPro of SARS-CoV-2 through in silico analysis. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2022, 13, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Verma, S. An in-silico evaluation of dietary components for structural inhibition of SARS-Cov-2 main protease. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, W. A Review of the Antiviral Role of Green Tea Catechins. Molecules 2017, 22, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhatre, S.; Naik, S.; Patravale, V. A molecular docking study of EGCG and theaflavin digallate with the druggable targets of SARS-CoV-2. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 129, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.; Park, Y.-I.; Cha, Y.-E.; Park, R.; Namkoong, S.; Lee, J.I.; Park, J. Tea polyphenols EGCG and theaflavin inhibit the activity of SARS-CoV-2 3CL protease in vitro. Evid. Based Complem. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 5630838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henss, L.; Auste, A.; Schürmann, C.; Schmidt, C.; von Rhein, C.; Mühlebach, M.D.; Schnierle, B.S. The green tea catechin epigallocatechin gallate inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Gen. Virol. 2021, 102, 001574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, M.; Jena, L.; Rath, S.N.; Kumar, S. Identification of Suitable Natural Inhibitor against Influenza A (H1N1) Neuraminidase Protein by Molecular Docking. Genom. Inf. 2016, 14, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, N.M.; Ismail, M.I.; El-Araby, A.M.; Bahgat, D.M.; Elissawy, A.M.; Mostafa, A.M.; Eldahshan, O.A.; Singab, A.N.B. Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Potential Inhibitory Activities of Some Natural Antiviral Compounds Via Molecular Docking and Dynamics Approaches. Phyton Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 91, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Hassandarvish, P.; Lani, R.; Yadollahi, P.; Jokar, A.; Bakar, S.A.; Zandi, K. Inhibition of chikungunya virus replication by hesperetin and naringenin. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 69421–69430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrillo, M.; Córdova, T.; Cabrera, G.; Rodríguez-Ortega, M. Effect of naringenin, hesperetin and their glycosides forms on the replication of the 17D strain of yellow fever virus. Avan. Biomed. 2015, 4, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Piva, H.M.R.; Sá, J.M.; Miranda, A.S.; Tasic, L.; Fossey, M.A.; Souza, F.P.; Caruso, I. Insights into Interactions of Flavanones with Target Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus M2-1 Protein from STD-NMR, Fluorescence Spectroscopy, and Computational Simulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.W.; Tsai, F.J.; Tsai, C.H.; Lai, C.C.; Wan, L.; Ho, T.Y.; Hsieh, C.C.; Chao, P.D. Anti-SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease effects of Isatis indigotica root and plant-derived phenolic compounds. Antivir. Res. 2005, 68, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.-J.; Huynh, T.-K.; Yang, C.-S.; Hu, D.-W.; Shen, Y.-C.; Tu, C.-Y.; Wu, Y.-C.; Tang, C.-H.; Huang, W.-C.; Chen, Y.; et al. Hesperidin Is a Potential Inhibitor against SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depieri Cataneo, A.H.; Kuczera, D.; Koishi, A.C.; Zanluca, C.; Ferreira Silveira, G.; Bonato de Arruda, T.; Akemi Suzukawa, A.; Oliveira Bortot, L.; Dias-Baruffi, M.; Aparecido Verri, W., Jr.; et al. The citrus flavonoid naringenin impairs the in vitro infection of human cells by Zika virus. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frabasile, S.; Koishi, A.C.; Kuczera, D.; Silveira, G.F.; Verri, W.A., Jr.; Duarte Dos Santos, C.N.; Bordignon, J. The citrus flavanone naringenin impairs dengue virus replication in human cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, H.M.; El-Halawany, A.M.; Sirwi, A.; El-Araby, A.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Koshak, A.E.; Asfour, H.Z.; Awan, Z.A.; Elfaky, M.A. Repurposing of Some Natural Product Isolates as SARS-COV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors via In vitro Cell Free and Cell-Based Antiviral Assessments and Molecular Modeling Approaches. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clementi, N.; Scagnolari, C.; D’Amore, A.; Palombi, F.; Criscuolo, E.; Frasca, F.; Pierangeli, A.; Mancini, N.; Antonelli, G.; Clementi, M.; et al. Naringenin is a powerful inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 163, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayati, R.F.; Better, C.D.; Denis, D.; Komarudin, A.G.; Bowolaksono, A.; Yohan, B.; Sasmono, R.T. [6]-Gingerol inhibits chikungunya virus infection by suppressing viral replication. BioMed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6623400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinavel, T.; Palanisamy, M.; Palanisamy, S.; Subramanian, A.; Thangaswamy, S. Phytochemical 6-Gingerol—A promising Drug of choice for COVID-19. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 1482–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, H.M.; El-Halawany, A.M.; Darwish, K.M.; Algandaby, M.M.; Mohamed, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.R.M.; Koshak, A.E.; Elhady, S.S.; Fadil, S.A.; Alqarni, A.A.; et al. Bio-Guided Isolation of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitors from Medicinal Plants: In vitro Assay and Molecular Dynamics. Plants 2022, 11, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praditya, D.; Kirchhoff, L.; Bruning, J.; Rachmawati, H.; Steinmann, J.; Steinmann, E. Anti-infective properties of the golden spice curcumin. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baikerikar, S. Curcumin and natural derivatives inhibit Ebola viral proteins: An in silico approach. Pharmacogn. Res. 2017, 9, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goc, A.; Sumera, W.; Rath, M.; and Niedzwiecki, A. Phenolic compounds disrupt spike-mediated receptor-binding and entry of SARS-CoV-2 pseudo-virions. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goc, A.; Rath, M.; Niedzwiecki, A. Composition of naturally occurring compounds decreases activity of Omicron and SARS-CoV-2 RdRp complex. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2022, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, G.; Maisto, M.; Schisano, C.; Ciampaglia, R.; Narciso, V.; Tenore, G.C.; Novellino, E. Resveratrol as a novel antiherpes simplex virus nutraceutical agent: An overview. Viruses 2018, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Gu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Ji, Y.; Sun, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, J.; et al. Resveratrol Inhibits Enterovirus 71 Replication and Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion in Rhabdosarcoma Cells through Blocking IKKs/NFκB Signaling Pathway. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahedi, H.M.; Ahmad, S.; Abbasi, S.W. Stilbene-based natural compounds as promising drug candidates against COVID-19. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Ellen, B.M.; Dinesh Kumar, N.; Bouma, E.M.; Troost, B.; van de Pol, D.P.I.; van der Ende-Metselaar, H.H.; Apperloo, L.; van Gosliga, D.; van den Berge, M.; Nawijn, M.C.; et al. Resveratrol and Pterostilbene Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Replication in Air–Liquid Interface Cultured Human Primary Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Viruses 2021, 13, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasquereau, S.; Nehme, Z.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; Daouad, F.; Van Assche, J.; Wallet, C.; Schwartz, C.; Rohr, O.; Morot-Bizot, S.; Herbein, G. Resveratrol inhibits HCoV-229E and SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus replication in vitro. Viruses 2021, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wei, J.; Huang, T.; Lei, L.; Shen, C.; Lai, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits the replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in cultured Vero cells. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, A.B.; Diamant, E.; Dor, E.; Barnea, A.; Natan, N.; Levin, L.; Chapman, S.; Mimran, L.C.; Epstein, E.; Zichel, R.; et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Inhibitors by In vitro Screening of Drug Libraries. Molecules 2021, 26, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xiu, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Qin, C.; Zhang, L. Chebulagic Acid, a Hydrolyzable Tannin, Exhibited Antiviral Activity in vitro and in Vivo against Human Enterovirus 71. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9618–9627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesharwani, A.; Polachira, S.K.; Nair, R.; Agarwal, A.; Mishra, N.N.; Gupta, S.K. Anti-HSV-2 activity of Terminalia chebula Retz extract and its constituents, chebulagic and chebulinic acids. BMC Complem. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Cooper, L.; Chen, Z.; Lee, H.; Rong, L.; Cui, Q. Discovery of chebulagic acid and punicalagin as novel allosteric inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. Antivir. Res. 2021, 190, 105075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Xiu, J.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C.; Liu, J. Antiviral activity of punicalagin toward human enterovirus 71 in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine 2012, 20, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunkumar, J.; Rajarajan, S. Study on antiviral activities, druglikeness and molecular docking of bioactive compounds of Punica granatum L. to herpes simplex virus - 2 (HSV-2). Microb Pathog 2018, 118, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suručić, R.; Tubić, B.; Stojiljković, M.P.; Djuric, D.M.; Travar, M.; Grabež, M.M.; Šavikin, K.; Škrbić, R. Computational study of pomegranate peel extract polyphenols as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 virus internalization. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 1179–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Gu, Y.; Xu, P. A Roadmap to Engineering Antiviral Natural Products Synthesis in Microbes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 66, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, T.; Habib, A.H.; Rafeeq, M.M.; Alafnan, A.; Khafagy, E.-S.; Iqbal, D.; Jamal, Q.M.S.; Unissa, R.; Sharma, D.C.; Moin, A.; et al. Oleuropein as a Potent Compound against Neurological Complications Linked with COVID-19: A Computational Biology Approach. Entropy 2022, 24, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Pandey, A.; Manvati, S. Coumarin: An emerging antiviral agent. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdizadeh, R.; Hadizadeh, F.; Abdizadeh, T. In silico analysis and identification of antiviral coumarin derivatives against 3-chymotrypsin-like main protease of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Mol. Divers 2022, 26, 1053–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, M.; Köksoy, B.; Ceyhan, D.; Sayın, K.; Erçağ, E.; Bulut, M.; Yalçın, B. Design and in silico study of the novel coumarin derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 main enzymes. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 27, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Y. Identification of the dietary supplement capsaicin as an inhibitor of Lassa virus entry. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahn, A.; Castillo, A. Potential of sulforaphane as a natural immune system enhancer: A review. Molecules 2021, 26, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordonez, A.A.; Bullen, C.K.; Villabona-Rueda, A.F.; Thompson, E.A.; Turner, M.L.; Merino, V.F.; Yan, Y.; Kim, J.; Davis, S.L.; Komm, O.; et al. Sulforaphane exhibits antiviral activity against pandemic SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal HCoV-OC43 coronaviruses in vitro and in mice. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouf, R.; Uddin, S.J.; Sarker, D.K.; Islam, M.T.; Ali, E.S.; Shilpi, J.A.; Nahar, L.; Tiralongo, E.; Sarker, S.D. Antiviral potential of garlic (Allium sativum) and its organosulfur compounds: A systematic update of pre-clinical and clinical data. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 104, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekh, S.; Reddy, K.K.A.; Gowd, K.H. In silico allicin induced S-thioallylation of SARS-CoV-2 main protease. J. Sulf. Chem. 2021, 42, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Saleem, M.; Saadullah, M.; Yaseen, H.S.; Al Zarzour, R. COVID-19 and therapy with essential oils having antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties. Inflammopharmacology 2020, 28, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, T.; Anantpadma, M.; Freundlich, J.S.; Davey, R.A.; Madrid, P.B.; Ekins, S. The Natural Product Eugenol Is an Inhibitor of the Ebola Virus In vitro. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuti, B.; Ceballos-Laita, L.; Ortega-Alarcon, D.; Jimenez-Alesanco, A.; Vega, S.; Grande, F.; Conforti, F.; Abian, O.; Velazquez-Campoy, A. Sub-Micromolar Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro by Natural Compounds. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paidi, R.K.; Jana, M.; Raha, S.; McKay, M.; Sheinin, M.; Mishra, R.K.; Pahan, K. Eugenol, a Component of Holy Basil (Tulsi) and Common Spice Clove, Inhibits the Interaction Between SARS-CoV-2 Spike S1 and ACE2 to Induce Therapeutic Responses. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021, 16, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musarra-Pizzo, M.; Pennisi, R.; Ben-Amor, I.; Mandalari, G.; Sciortino, M.T. Antiviral Activity Exerted by Natural Products against Human Viruses. Viruses 2021, 13, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.P., 3rd; Kajon, A.E. Adenovirus: Epidemiology, global spread of novel serotypes, and advances in treatment and prevention. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 37, 586–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Si, H.; Yu, Z.; Tian, S.; Xiang, R.; Deng, X.; Liang, R.; Jiang, S.; Yu, F. Influenza virus glycoprotein-reactive human monoclonal antibodies. Microbes Infect. 2020, 22, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacelar Júnior, A.J.; Vieira Andrade, A.L.; Gomes Ferreira, A.A.; Andrade Oliveira, S.M.; Silva Pinheiro, T. Human Immunodeficiency Virus—HIV: A Review. Braz. J. Surg. Clin. Res. 2015, 9, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Virus Taxonomy: The Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. The 9th Report of the ICTV. ICTV. 2011. Available online: https://ictv.global/report_9th (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Yin, Y.; Wunderink, R.G. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology 2018, 23, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Statement Regarding Cluster of Pneumonia Cases in Wuhan, China; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/china/news/detail/09-01-2020-who-statement-regarding-cluster-of-pneumonia-cases-in-wuhan-china (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Disease Outbreak News Update. Novel Coronavirus—China 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2020-DON233 (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Kanjanasirirat, P.; Suksatu, A.; Manopwisedjaroen, S.; Munyoo, B.; Tuchinda, P.; Jearawuttanakul, K.; Seemakhan, S.; Charoensutthivarakul, S.; Wongtrakoongate, P.; Rangkasenee, N.; et al. High-content screening of Thai medicinal plants reveals Boesenbergia rotunda extract and its component Panduratin A as anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.R.; Cao, Q.D.; Hong, Z.S.; Tan, Y.-Y.; Chen, S.-D.; Jin, H.-J.; Tan, K.-S.; Wang, D.-Y.; Yan, Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—An update on the status. Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestle, D.; Heindl, M.R.; Limburg, H.; Van Lam van, T.; Pilgram, O.; Moulton, H.; Stein, D.A.; Hardes, K.; Eickmann, M.; Dolnik, O.; et al. TMPRSS2 and furin are both essential for proteolytic activation of SARS-CoV-2 in human airway cells. Life Sci. Allianc. 2020, 3, e202000786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Wu, N.C.; Zhu, X.; Lee, C.D.; So, R.T.Y.; Lv, H.; Mok, C.K.P.; Wilson, I.A. A highly conserved cryptic epitope in the receptor-binding domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Science 2020, 368, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillen, H.S.; Kokic, G.; Farnung, L.; Dienemann, C.; Tegunov, D.; Cramer, P. Structure of replicating SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. Nature 2020, 584, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.L.; Andurkar, S.V. A review of natural products, their effects on SARS-CoV-2 and their utility as lead compounds in the discovery of drugs for the treatment of COVID-19. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keflie, T.S.; Biesalski, H.K. Micronutrients and bioactive substances: Their potential roles in combating COVID-19. Nutrition 2021, 84, 111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, E.; Zhang, D.; Luo, H.; Liu, B.; Zhao, K.; Zhao, Y.; Bian, Y.; Wang, Y. Treatment efficacy analysis of traditional Chinese medicine for novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19): An empirical study from Wuhan, Hubei Province. China Chin. Med. 2020, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R.; Srivastava, S.; Ghosh, S.; Khare, S.K. Phytochemical delivery through nanocarriers: A review. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2021, 197, 111389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pierro, F.; Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Bertuccioli, A.; Togni, S.; Riva, A.; Allegrini, P.; Khan, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, B.A.; et al. Possible Therapeutic Effects of Adjuvant Quercetin Supplementation Against Early-Stage COVID-19 Infection: A Prospective, Randomized, Controlled, and Open-Label Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 2359–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pierro, F.; Iqtadar, S.; Khan, A.; Ullah Mumtaz, S.; Masud Chaudhry, M.; Bertuccioli, A.; Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Togni, S.; Riva, A.; et al. Potential Clinical Benefits of Quercetin in the Early Stage of COVID-19: Results of a Second, Pilot, Randomized, Controlled and Open-Label Clinical Trial. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 2807–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondanelli, M.; Perna, S.; Gasparri, C.; Petrangolini, G.; Allegrini, P.; Cavioni, A.; Faliva, M.A.; Mansueto, F.; Patelli, Z.; Peroni, G.; et al. Promising Effects of 3-Month Period of Quercetin Phytosome® Supplementation in the Prevention of Symptomatic COVID-19 Disease in Healthcare Workers: A Pilot Study. Life 2022, 12, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCreary, M.R.; Schnell, P.M.; Rhoda, D.A. Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled proof-of-concept trial of resveratrol for outpatient treatment of mild coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, H.; Abdolmohammadi-Vahid, S.; Danshina, S.; Ziya Gencer, M.; Ammari, A.; Sadeghi, A.; Roshangar, L.; Aslani, S.; Esmaeilzadeh, A.; Ghaebi, M.; et al. Nano-curcumin therapy, a promising method in modulating inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 89, 107088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber-Moghaddam, N.; Salari, S.; Hejazi, S.; Amini, M.; Taherzadeh, Z.; Eslami, S.; Rezayat, S.M.; Jaafari, M.R.; Elyasi, S. Oral nano-curcumin formulation efficacy in management of mild to moderate hospitalized coronavirus disease-19 patients: An open label nonrandomized clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 2616–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, R.; Salari, S.; Sharifi, M.D.; Reihani, H.; Rostamiani, M.B.; Behmadi, M.; Taherzadeh, Z.; Eslami, S.; Rezayat, S.M.; Jaafari, M.R.; et al. Oral nano-curcumin formulation efficacy in the management of mild to moderate outpatient COVID-19: A randomized triple-blind placebo controlled clinical trial. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 4068–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).