1. Introduction

E-commerce platforms (i.e., e-platforms), such as JD in China and Amazon in the United States, are rapidly expanding in the digital economy. According to a report by MobiLoud [

1], the worldwide sales of e-platforms will reach USD 6 trillion by 2024 and constitute 19.5% of total global retail sales. E-platforms can play two roles: cooperation and competition with upstream manufacturers in the context of the supply chain [

2,

3,

4]. On the one hand, an e-platform can act as a traditional retailer (i.e., reseller) to purchase products from the manufacturer and then sell them to the final customers. However, an e-platform can also act as an agency seller to provide a sales platform and charge an agency fee to the manufacturer. For example, JD, a famous e-platform in China, not only has a self-operated store for purchasing products from the manufacturer but also acts as an agency seller to allow upstream manufacturers to develop retail channels on their platform. It is evident that cooperation and competition exist in e-platform supply chains.

In recent years, live-streaming e-commerce has become a popular and promising way of promotion on e-platforms [

5,

6,

7]. There are two popular modes of live-streaming e-commerce in e-platform supply chains. First, the manufacturer can invite a key opinion leader (KOL) for live promotions and to sell products on e-platforms. The KOL means someone who has a large following to sell products online by showcasing their functions and performance for consumers within a fixed period [

8]. They will take advantage of their own talent and popularity to attract consumers and increase their willingness to purchase and promote products. For example, Casey Holmes is a famous beauty blogger with millions of YouTube subscribers who cooperates with beauty brands to promote their products on the Amazon platform. In addition, Austin Li, who is the top KOL in China, achieved a gross merchandise volume of over CNY 2.5 billion on the first day of the “618” shopping festival in 2025 (

https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20250515A00L6S00, accessed on 20 January 2025). Second, the manufacturer can choose to use the self-broadcasting mode to sell products on an e-platform. Under self-broadcasting, the manufacturer can cultivate employees who will showcase the quality and functions of products in more detail to attract customers. Thus, the sales performance of self-broadcasting should not be underestimated. For example, Haier, a well-known home appliance manufacturer in China, trained a professional self-broadcasting group and reached sales of USD 100 million in 52 min on the Tmall e-platform during the Double 11 period.

According to the above analysis, KOL live-streaming and manufacturer self-broadcasting are important methods to rapidly expand selling quantities for brands, especially for beauty and home appliance brands. If a manufacturer chooses KOL live-streaming, he can take advantage of the KOL’s influence level to expand selling quantities and clear inventory in the short term. However, many manufacturers believe that the repurchase rate is low and the return rate is high in the KOL’s live room, and the high commission fee makes many brands hesitate. Therefore, some manufacturers have turned to building their own self-broadcasting room. If the manufacturer chooses self-broadcasting, he can save on the cost of the KOL live-streaming, but there will be fewer potential customers. Therefore, it is difficult for the manufacturer to choose a suitable strategy for live-streaming e-commerce in an e-platform-based dual-channel supply chain when facing a complex environment of cooperation and competition. Motivated by the above analysis, we considered three scenarios: benchmark (i.e., B scenario, without live-streaming e-commerce), KOL live-streaming (i.e., L scenario), and manufacturer self-broadcasting (i.e., S scenario), to explore the most suitable mode selection for the manufacturer. We set the following three research questions: (1) What are the equilibrium decisions of the two supply-chain members in scenarios B, L, and S? (2) How do different key factors (e.g., the KOL’s influence level, channel preference, and shared ratio for the KOL) influence the equilibrium decisions of the two supply-chain members under the three different scenarios? (3) Which mode of live-streaming e-commerce should the manufacturer choose to achieve a better profit?

To answer these research questions, we employed Stackelberg game theory to build a corresponding mathematics model. Due to its modeling advantages in sequential decision-making and power asymmetry, this theory has become an ideal tool for analyzing the strategic interactions between different decision-makers, especially for research issues such as channel conflicts, pricing power competition, and supply-chain coordination. In this study, we considered a supply chain consisting of one manufacturer and one e-platform. The e-platform purchases products from the manufacturer and sells them to the final market. Meanwhile, the manufacturer will choose one mode (i.e., cooperate with a KOL or self-broadcasting) of live-streaming e-commerce to develop a new channel, engaging in pricing competition with the e-platform. We established three mathematical models for scenarios B, L, and S. Then, the equilibrium decisions were driven to explore the impact of the KOL’s influence level, channel preference, and shared ratio on the live-streaming strategies of the manufacturer as well as the profits of the e-platform.

Although many studies have focused on strategies for live-streaming commerce in the context of the supply chain [

8,

9], few have considered whether the manufacturer chooses either KOL live-streaming or self-broadcasting to sell products on the e-platform, which acts as a reseller and agency seller. The main contribution of this study is that it explored the strategy for live-streaming e-commerce in the context of a platform-based dual-channel supply chain. The key findings of this study are as follows: Even if the influence level of the KOL is within a low range, the manufacturer should change his strategy from no live-streaming e-commerce to KOL live-streaming, with a decrease in the agency fee charged by the e-platform. However, with a continued decline in agency fees, the manufacturer should change strategy from KOL live-streaming to self-broadcasting. This is because KOL live-streaming wipes out the advantage of a higher sharing ratio and lower influence level when the channel cost (i.e., agency fee) of the manufacturer is in a very low range. Furthermore, we found a win–win zone for the two supply-chain members under the L scenario, when both the agency fee of the e-platform and the influence level of the KOL are in higher ranges.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we explore two streams within the literature: dual-channel supply chain and live-streaming e-commerce. The problem descriptions and notations are presented in

Section 3. In

Section 4, we establish three Stackelberg models under scenarios B, L, and S and derive the equilibrium decisions of the two supply-chain members under each scenario. In

Section 5, we compare the equilibrium decisions and profits of the two supply-chain members under the three different scenarios. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes our contributions and managerial insights.

3. Problem Description

The Stackelberg game is used to characterize power and is suitable for simulating hierarchical relationships in reality (e.g., upstream and downstream enterprises in the supply chain). In some scenarios where strategic interactions need to be analyzed and there is a clear first-mover advantage, it is more explanatory and practical than other traditional methods. The method has been widely adopted in the platform economy and supply-chain management [

28,

29,

30]. To observe the behavior of the manufacturer and the e-platform, then, we construct a Stackelberg game model where the manufacturer is the leader and the e-platform is the follower. In this section, we consider a supply chain with one manufacturer (he) and one e-platform (she) to explore whether the manufacturer introduces self-broadcasting or KOL live-streaming to compete with the e-platform in the final market. In a traditional selling channel, the manufacturer sells products to the e-platform through a traditional wholesale contract and then sells the products to the final consumers. A manufacturer sells products to final customers on an e-platform in two ways: manufacturer self-broadcasting or KOL live-streaming, leading to competition with the e-platform. Therefore, we consider three scenarios: (1) the B scenario, in which the manufacturer will choose neither KOL live-streaming nor self-broadcasting; (2) the L scenario, in which the manufacturer collaborates with a KOL to attract more consumers, and revenue will be partially shared with the KOL; and (3) the S scenario, in which the manufacturer conducts self-broadcasting to attract consumers. The supply-chain structure is shown in

Figure 1, and M indicates the manufacturer. The notations and descriptions are presented in

Table 1.

Under the B scenario, the manufacturer chooses neither to self-broadcast nor to use KOL live-streaming, and the sequence of events between the supply-chain members is as follows: the manufacturer first decides the wholesale price, and then the e-platform decides the retail price. Under the L scenario, the manufacturer first decides the wholesale price, the manufacturer and e-platform simultaneously decide the selling prices in their respective channels, and finally, the KOL determines the effort level. At the end of the selling season, the manufacturer pays the unit commission fee to the KOL and the unit agency fee to the e-platform. Under the S scenario, the manufacturer first decides the wholesale price, and then the manufacturer and the e-platform simultaneously decide their selling prices. Finally, the manufacturer determines the effort level and bears the corresponding investment costs for self-broadcasting. After self-broadcasting, the manufacturer pays a unit fee to the e-platform.

Based on previous studies [

31,

32], we assume that each consumer has a heterogeneous product value and that the consumer value follows a uniform distribution between 0 and 1; that is,

. Under the B scenario, consumer utility is

, where

is the e-platform’s retail price. Thus, we can deduce that the demand for an e-platform self-stored channel is

. Because the e-platform can provide better logistics and after-sales services, consumers are more inclined to purchase products from the self-stored e-platform channel. Therefore, we assume that the consumer preference for a live-streaming channel is

(

); the consumer values purchased from a live-streaming channel and an e-platform self-stored channel are

and

, respectively. The traffic-driving ability of KOL live-streaming is higher than that of manufacturer self-broadcasting, and consumers have greater utility when buying products from KOL live-streaming. This indicates that KOL live-streaming has a higher influence level to attract consumers than manufacturer self-broadcasting; thus, we consider a positive influence level

for consumer utility bought from KOL live-streaming. Thus, under the L scenario, the consumer utility bought from KOL live-streaming is

. Furthermore, the e-platform sells products to the consumer, engaging in pricing competition with the KOL live-streaming channel. The consumer utility from the self-stored e-platform is

. If the consumer utility

and

, the consumer will choose the KOL live-streaming channel to buy products; if

and

, then the consumer will turn to the e-platform self-stored channel to buy products. In addition, the KOL attracts more consumers through professional evaluation and the sales effort level. Thus, the demand for KOL live-streaming is positively influenced by the effort level

of the KOL. Referring to the previous literature on live-streaming e-commerce [

19,

33], we assume that the effort level of the KOL has a direct impact on the demand for the live-streaming channel. Thus, the demand functions of the KOL live-streaming channel and e-platform under the L scenario are as follows:

Under the S scenario, the consumer utility from the manufacturer’s self-broadcasting channel is

, and the consumer utility from the e-platform self-stored channel is

. If

and

, consumers will choose to purchase products from the manufacturer’s self-broadcasting channel; if

and

, consumers will choose to purchase products from the KOL live-streaming channel. During the self-broadcasting process, the manufacturer also needs to make a service effort to attract more consumers to purchase products. Under the S scenario, the demand functions of the manufacturer’s self-broadcasting channel and e-platform are shown as follows, respectively:

5. Comparative Analysis

In this section, we compare and analyze the optimal wholesale price of the manufacturer, the optimal retail prices of the manufacturer and the e-platform, and their optimal profits under three scenarios. Corresponding management insights are then provided to the supply-chain members. In particular, we analyze whether the manufacturer wants to introduce a KOL live-streaming channel or a self-broadcasting channel to compete with the e-platform self-stored channel.

Proposition 1. Under three scenarios, the optimal wholesale price will be influenced by the channel preferences of consumers, the influence level of the KOL, and the commission and agency fees. The specific comparison results are shown in Table 2. When the influence level for the KOL is within a low range (i.e., ) and the agency fee charged by the e-platform is high (i.e., ), the optimal wholesale price decided by the manufacturer under the B scenario is higher than that under the other two scenarios. The low influence of the KOL indicates that it is difficult to attract more consumers to buy products through the KOL live-streaming channel. A higher unit agency fee indicates that the manufacturer will incur a higher cost to sell the product on the e-platform by introducing a KOL live-streaming or self-broadcasting channel. We can draw an abnormal conclusion: the optimal wholesale price of the manufacturer under the B scenario is higher than in the other scenarios. The main reason is that, although the low influence level of the KOL and high agency cost charged by the e-platform will reduce the revenue of the manufacturer, introducing a KOL live-streaming channel or a manufacturer self-broadcasting channel will mitigate the double-marginalization effect. Thus, the traditional wholesale price decided by the manufacturer under the B scenario is higher than under the L and S scenarios. In addition, when the e-platform has a higher commission fee (i.e., ), the agency fee is low (i.e., ), and the influence level is high (), the optimal wholesale price of the manufacturer under the B scenario is also higher than the remaining two scenarios. The reason is that the influence level is within a relatively high range, and the KOL live-streaming channel will attract more consumers; the low commission fee paid by the manufacturer further decreases the operating cost of the manufacturer by introducing a KOL live-streaming channel. Therefore, the manufacturer reduces the dual-marginalization effect of the supply chain by introducing a KOL live-streaming channel or a manufacturer self-broadcasting channel, thereby lowering the wholesale price.

When the consumer has a high preference for a new-added channel (i.e., ) and the commission fee is low (), there are two situations where the optimal wholesale price of the manufacturer under the S scenario is higher than that under the B and L scenarios. Specifically, (1) when the agency fee is low () or (2) when the agency fee is high () and the influence level is low (), then holds. Firstly, if the consumer has a high preference for the new-added channel and the agency fee is low, this indicates that the manufacturer has a high demand for the new-added channel, which is close to the potential market demand of the traditional channel, and the selling cost is low through the KOL live-streaming channel or the manufacturer’s self-broadcasting channel. This finding is contrary to the traditional belief that the manufacturer sets a lower wholesale price for the e-platform in a dual-channel situation, thereby reducing the dual-marginalization effect of the supply chain, and a lower agency fee will further decrease the wholesale price decision of the manufacturer. In an abnormal situation, if the commission fee is relatively low, the manufacturer will set a lower wholesale price because of the lower cost of KOL live-streaming under the L scenario. Secondly, when the agency fee is high () and the influence level is low (), we can obtain the same result . Although a higher commission fee will increase the operating cost and prompt the manufacturer to charge a higher wholesale price to the e-platform, a lower influence level may cause lower demand under the L scenario than that under the S scenario. If the consumer has a higher preference for the new-added channel and the e-platform charges a lower agency fee, this encourages the manufacturer to set a lower wholesale price for the e-platform.

When the consumer has a high preference for the new live-streaming channel () and the agency fee is within a low range (), while the commission fee is high () and the influence level is within a medium range (), the optimal wholesale price under the L scenario is higher than that under the B and S scenarios. Compared with the scenario where the influence level is relatively low (), when the is improved to a medium range, the manufacturer sets the wholesale price under the L scenario as higher than under the other scenarios. The main reason is that an increase in the influence level leads to an increase in demand under the L scenario, thereby giving the manufacturer greater bargaining power to make wholesale price decisions for the e-platform.

Proposition 2. Under the S and L scenarios, the comparison outcomes of the retail price of the manufacturer are influenced by the influence level of the KOL and the agency and commission fees. It can be divided into three situations: (a) when and , then holds; (b) when and ; and (c) when , the comparison result of the retail price for the manufacturer is influenced by the influence level of the KOL, and there exists a unique to satisfy . When , then holds; when , then holds.

Proposition 2 demonstrates that the retail price decisions of the manufacturer, KOL live-streaming channel, and manufacturer self-broadcasting channel mainly depend on the influence level of the KOL and the agency and commission fees. When the agency fee is low () and the commission fee is high (), the retail price set by the manufacturer under the L scenario is higher than that under the S scenario. This is because a lower agency fee decreases the operating cost of the manufacturer for the new-added channel, but a higher commission fee increases the cost of KOL live-streaming. Thus, the manufacturer will increase the retail price to reduce the cost of paying the KOL commission fee. When the agency fee is high () and the commission fee is high (), the retail price set by the manufacturer under the L scenario is also higher than that under the S scenario. Although a higher agency fee for the e-platform increases the operating cost of the manufacturer for the new-added channel, a higher influence level increases the competitiveness of the manufacturer in the KOL live-streaming channel, resulting in greater bargaining power under the L scenario than that under the S scenario. In addition, when the agency fee is relatively high () and the influence level of the KOL is relatively low (), the retail price set by the manufacturer under the L scenario is lower than the S scenario. This is because a higher agency fee increases the operating cost of the manufacturer in the KOL live-streaming or self-broadcasting channel, whereas a lower influence level reduces competitiveness in the KOL live-streaming channel. Therefore, the manufacturer will set a lower price to attract more consumers and compensate for the higher operating cost under the L scenario.

Proposition 3. Under the three scenarios, the optimal retail price of the e-platform mainly depends on the channel preferences of consumers, the commission fee, the influence level, and the agency fee. The comparison outcomes are listed in Table 3. Proposition 3 shows that when the consumer has a low preference for the live-streaming channel (i.e., ) and the e-platform charges a high agency fee (), the retail price decided by the e-platform under the B scenario is higher than that under the L and S scenarios. The traditional wisdom is that the e-platform occupies a substantial competitive position in the final market because the manufacturer will have fewer potential customers and bear the higher cost of a live-streaming channel. On the contrary, the e-platform still sets a lower retail price under the B scenario than that under the L and S scenarios to attract more customers. However, according to the results of Proposition 1, when the agency fee is high, the wholesale price decision of the manufacturer under the B scenario is higher than that in the other scenarios. The manufacturer’s decision to set a higher wholesale price under the B scenario can prompt the e-platform to set a higher retail price under the B scenario, thereby alleviating the high operating cost of the e-platform. On the other hand, the consumer has a lower preference for the new-added channel of the manufacturer, leading to reduced competition between the manufacturer and e-platform in the end market. Consequently, the retail prices of the e-platform under the L and S scenarios are lower than those under the B scenario, attracting more customers to purchase products and boosting the revenue of the manufacturer. The e-platform can obtain higher profits by charging a higher agency fee to the manufacturer. In addition, the retail price decision of the e-platform under the S scenario is higher than that under the L scenario. If the consumer has a low preference for the manufacturer, then the potential market demand for the manufacturer on the new channel is small. If an e-platform charges a higher agency fee to the manufacturer, the larger the sales volume in the new-added channel and the more advantageous it is for the e-platform. Compared with the S scenario, KOL live streaming has a certain influence level. Meanwhile, the retail price set by the e-platform under the L scenario is lower than that under the S scenario, thereby promoting demand for the KOL live-streaming channel and obtaining more agency fee.

When the agency fee () and commission fee () are in the lower range, the retail price decided by the e-platform under the B scenario is higher than that under the S scenario. A lower agency fee reduces the manufacturer’s operational costs in the live-streaming channel; thus, the dual-marginalization effect is further reduced in the dual-channel supply chain. This incentivizes the manufacturer to charge a lower wholesale price to the e-platform under S and L scenarios, thereby promoting e-platform to make lower retail price decisions in both scenarios compared to the benchmark scenario. Therefore, the e-platform is motivated to set lower retail prices in both scenarios than those under the B scenario. In addition, if the commission fee is low, the operating cost of the manufacturer can also be reduced under the L scenario, thereby increasing demand for the KOL live-streaming channel. The e-platform can decide on a lower retail price under the L scenario to alleviate competition with the manufacturer in the end market, thereby gaining more shared revenue from the manufacturer. Moreover, if the commission fee () and influence level () are all high, the above conclusion still holds. However, if the commission fee is high () and the influence level is low (), the retail price decision of the e-platform under the L scenario is higher than that under the S scenario. This result illustrates that a higher agency fee increases the advantage of the e-platform with a decreasing influence level. As the influence level is within a lower range, even if the e-platform raises the retail price, the demand for the retail channel does not shift to the manufacturer’s new live-streaming channel.

Traditionally, the consumers’ higher channel preference reduces the advantage of the retail channel; thus, e-platform may set a lower retail price to attract more consumers. Nevertheless, even if the consumer has a higher channel preference (), if the commission and agency fee are both high, the retail price decided by the e-platform under the B scenario is lower than that under either the L or S scenario. In addition, a higher commission fee causes the retail price decided by the e-platform under the L scenario to be higher than that under the S scenario. A higher agency fee increases the e-platform’s revenue and reduces the retail price to attract more consumers. However, the retail prices decided by the e-platform under the B scenario are higher than those under the L and S scenarios. This is because, although a higher agency fee will further increase the revenue of the e-platform, the dual-marginalization effect of the supply chain is still further weakened compared to that under the B scenario, thereby reducing the wholesale price of KOL live-streaming and manufacturer self-broadcasting in the supply chain.

When consumers have a higher channel preference (), the influence level of the KOL is low (), and the agency fee is high (), the optimal retail price of the e-platform is under the three different scenarios. A higher preference for the live-streaming channel will bring more potential consumers, and thus, the bargaining power of the manufacturer will increase. However, a lower influence level indicates that it is difficult to attract more consumers to the manufacturer by introducing KOL live-streaming, thus inducing the manufacturer to make the decision to lower pricing to attract consumers. As a result, it is also unnecessary for the e-platform to set higher retail pricing under the L scenario, notwithstanding the loss of agency revenue from the manufacturer. Moreover, although a higher consumer preference for the live-streaming channel increases the competitiveness of self-broadcasting, the manufacturer is still inferior to the traditional e-platform channel with a higher agency fee. Consequently, the e-platform is motivated to set the highest retail pricing under the S scenario. When the influence level of the KOL is low (), the retail pricing set by the e-platform under the B scenario will be higher than the retail price under the L scenario. This is because a higher agency fee leads to a higher operating cost for the manufacturer in the live-streaming channel of the KOL. In addition, the weaker influence level of the KOL will lead to the loss of customers for the manufacturer in the KOL live-streaming channel; thus, the manufacturer is motivated to increase the wholesale price. Consequently, the e-platform will set the lowest retail price under the KOL live-streaming channel to prevent the manufacturer from setting a higher wholesale price. When the commission fee is low (), even if the influence level is high, (), still holds. The main reason for this is that when the commission fee is low and the influence level is high, the manufacturer has stronger bargaining power on the KOL live-streaming channel. Therefore, if the e-platform sets a higher retail price, it will increase the competition between the manufacturer and the e-platform in the final market, resulting in a loss of profit for both the manufacturer and the e-platform.

When the commission fee is high () and the agency fee is low (), the higher influence level of the KOL () will encourage the e-platform to set a higher retail price under the S scenario than that under the L scenario, while the e-platform sets the lowest retail price under the B scenario. Specifically, although the influence level of the KOL attracts more customers to purchase products on the KOL live-streaming channel, the manufacturer still needs to pay a higher commission fee and share more revenue with the KOL. Therefore, it is unnecessary for the e-platform to set a higher retail price to increase competition under the L scenario. Moreover, a lower agency fee reduces the e-platform’s revenue earned from the manufacturer’s self-broadcasting channel. Consequently, the e-platform should set a higher retail price under the S scenario.

Proposition 4. Under the S and L scenarios, the comparison outcomes of the degree of effort of the KOL are influenced by the influence level of the KOL and the agency and commission fees. This can be divided into three situations: (a) when ; (b) when and , then holds; (c) when and , then holds.

Proposition 4 shows that the comparison results between the effort degrees under KOL live-streaming and the manufacturer self-broadcasting are jointly influenced by the influence level and commission degree. When the influence level is low (), the degree of effort under the S scenario is higher than under the L scenario. However, if the influence level is high () and the commission fee is low (), the degree of effort decided by the manufacturer is still higher than that decided by the KOL. With a higher influence level and lower commission fee, the traditional wisdom is that the KOL will improve the degree of effort to increase market demand, enjoying the lower cost of the live-streaming channel for the manufacturer. However, a lower commission fee will significantly reduce the motivation for the KOL’s effort. Thus, the degree of effort for KOL live-streaming is relatively low, and the manufacturer’s self-broadcasting degree of effort will still be higher than that of the KOL live-streaming. Nevertheless, if the influence level is high () and the commission fee is also high (), the degree of effort of the KOL is higher than that of the manufacturer. This is because a higher influence level of the KOL will attract more consumers, and a higher commission fee will further stimulate the KOL’s enthusiasm for live-streaming.

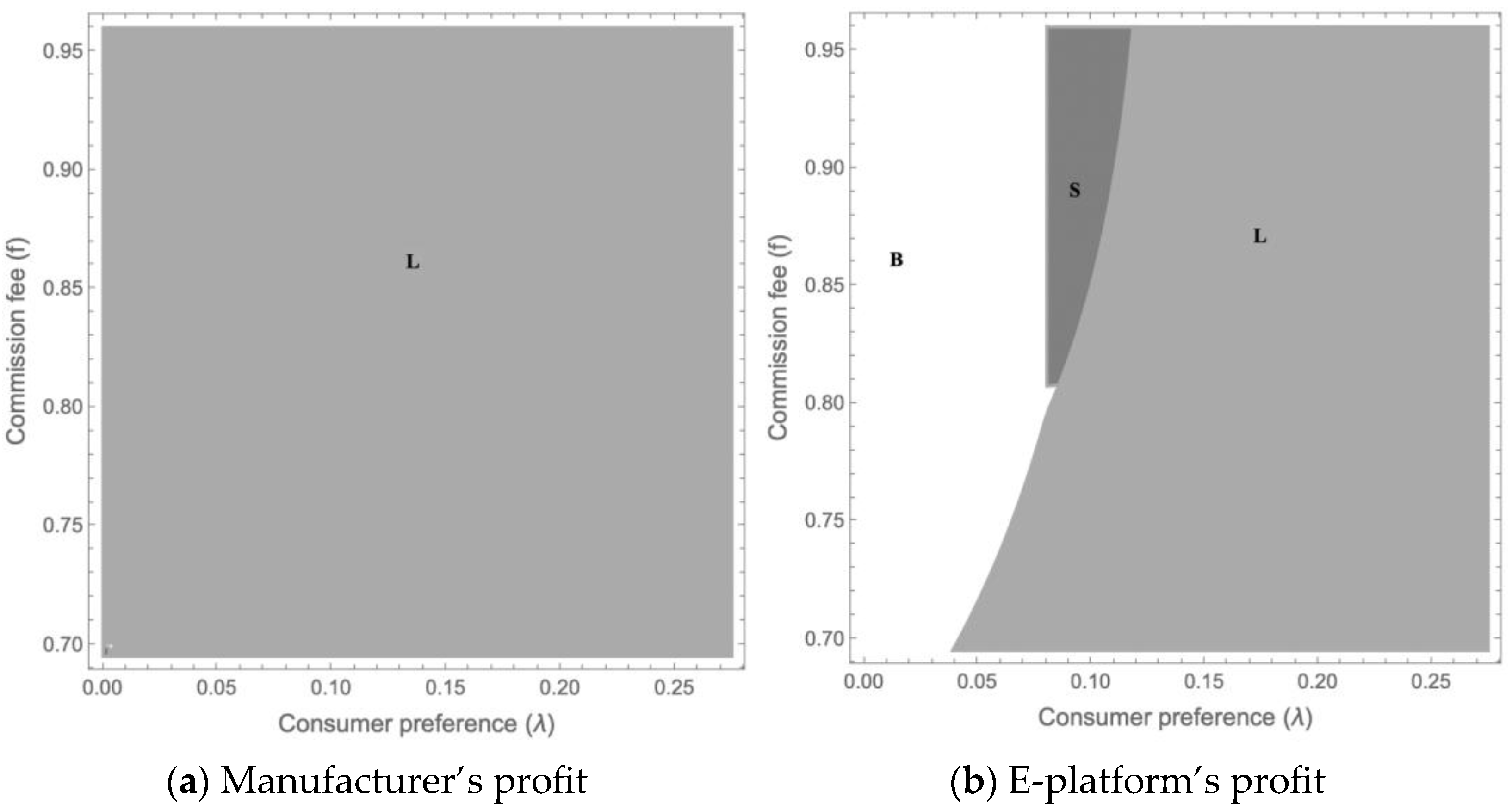

Proposition 5. Under these three scenarios, whether the manufacturer will introduce a live-streaming channel or a self-broadcasting channel mainly depends on the channel preferences of consumers, the commission fee, the influence level, and the agency fee. The comparison outcomes are displayed in Table 4. Proposition 5 illustrates that when the agency fee (

) and commission fee (

) are high but the influence level is low (

), regardless of the fluctuation in channel preference, the manufacturer has a lower profit from introducing a KOL live-streaming channel or self-broadcasting channel than that under the B scenario (see B zone in

Figure 2a). The rationale is that the operating cost of a new live-streaming channel for the manufacturer will be increased, but the KOL live-streaming or self-broadcasting cannot attract more potential customers, resulting in a negative performance for the manufacturer by introducing the channel for KOL live-streaming or self-broadcasting. Therefore, the manufacturer should choose the traditional wholesale mode and abandon live-streaming or the self-broadcasting channel. However, when the agency fee is within a moderate range (

) and the influence level (

) and commission fee (

) are high, the manufacturer is inclined to choose to introduce a KOL live-streaming channel to compete with the e-platform in the final market (see the L zone in

Figure 3a). Recalling Proposition 4, the reason is that a higher commission fee and influence level will induce the KOL to exert more effort under the L scenario. The higher influence level of the KOL with a greater degree of effort will promote a significant improvement in demand and revenue, which is sufficient to cover the higher operating costs from the commission and agency fees. Therefore, the manufacturer can choose a KOL live-streaming channel to increase demand and reduce the investment costs of promotions, resulting in a greater payoff. However, when the agency fee (

) and influence level (

) are within the lower ranges, the manufacturer will prefer to introduce a self-broadcasting channel. This is because, even if a lower agency fee reduces the operating cost of the manufacturer’s new-added channel, the lower influence level of the KOL will reduce the motivation to exert more effort in promotion. Thus, it is difficult to attract more customers to improve demand. Moreover, a lower agency fee will help the manufacturer save on the operating cost of a self-broadcasting channel, thereby investing more capital in promotion by self-broadcasting. Therefore, if both the agency fee and influence level are low, the manufacturer should choose to introduce a self-broadcasting channel.

According to the above analysis, the management implications of Proposition 5 can be summarized as follows. When the agency fee is higher but the influence level is lower, the upstream manufacturer should abandon the introduction of the KOL live-streaming or self-broadcasting channel. However, with a reduction in the agency fee, even if the influence level of the KOL is lower, the manufacturer should change strategy from a traditional single channel to introducing the KOL live-streaming channel, which can not only alleviate the dual-marginalization effect of traditional supply-chain channels but also reduce competition with the e-platform in the final market. With a gradual decrease in agency fees, the manufacturer should shift the strategy from opening a KOL live-streaming channel to adding a self-broadcasting channel. This is because the continuous reduction in agency fee may cause a gradual decrease in the operating cost of the manufacturer’s new-added channel, while the lower influence level of the KOL and higher commission fee will result in a higher cost for the live-streaming channel and a larger revenue share with the KOL.

Due to the complexity of the optimal profit for an e-platform, this study employs a numerical simulation method to further explore management insights from the perspective of the e-platform under three different scenarios.

Figure 2b shows that when the agency fee is lower and the influence level of the KOL is higher, the e-platform obtains the highest profit under the B scenario. Although the manufacturer can introduce the KOL live-streaming channel or their own self-broadcasting channel to alleviate the dual-marginalization effect of the supply chain, the manufacturer is highly competitive in setting a higher wholesale price and squeezing the e-platform because of the lower agency fee and higher influence level of the KOL. Consequently, the e-platform is more willing for the manufacturer to abandon the introduction of the KOL live-streaming channel or the manufacturer’s self-broadcasting channel.

When the agency fee and the KOL’s influence level are relatively low, the e-platform will gain the maximum profit under the L scenario compared to the other two scenarios. This is because, even though a lower agency fee reduces the operating cost for the manufacturer to introduce a live-streaming channel, it will be difficult to achieve the expected effect of the promotion using KOL live-streaming. Then, the double-marginalization effect of the supply chain can not only be reduced under the L scenario, but competition with the e-platform can also be reduced. In addition, the higher agency fee and influence level of the KOL will still induce the e-platform to gain maximum profit under the L scenario. This is because even if the higher influence level of the KOL can help the manufacturer obtain greater market demand through KOL live-streaming, a higher agency fee will help the e-platform obtain greater commission revenue from the KOL live-streaming channel. The higher agency fee and lower influence level of the KOL will induce the e-platform to always hope that the manufacturer will select the S scenario. The low influence level of the KOL will reduce the competitiveness of the manufacturer and lead to lower revenue after adopting KOL live-streaming, which cannot help the e-platform obtain a higher profit from the manufacturer. Additionally, the higher agency fee and lower influence level of the KOL will put the manufacturer in a weak position by adding a new channel, thereby increasing the wholesale price for the e-platform. Accordingly, the e-platform prefers to introduce a self-broadcasting channel (i.e., the S scenario) with a higher agency fee and lower influence level of the KOL. As shown in

Figure 2a,b, if both the agency fee and the influence level of the KOL are higher, the manufacturer and e-platform can achieve a win–win situation under the L scenario. In other words, there exists a Pareto zone with a higher agency fee and influence level of the KOL for the manufacturer and e-platform to obtain higher profits under the L scenario.

Figure 3b shows that when the commission fee is high and consumer preference is very low, the e-platform prefers the B scenario. It is obvious that if the manufacturer is not interested in new channels and the paid commission fee for the KOL is high, he will abandon the KOL live-streaming and self-broadcasting modes. In addition, if the commission fee is very high and the consumer preference is relatively low, the e-platform needs to be under the S scenario to obtain a higher profit. In other words, if the manufacturer is likely to accept new channels and the commission fee is high, the self-broadcasting mode is the optimal option. This is because the higher commission fee may lead the e-platform to be unwilling to implement the KOL live-streaming. With the increase in consumer preference, she will be inclined to the L scenario. The reason is that the higher the

, the more the manufacturer will gain more payoff from the L scenario, and then the e-platform will also obtain more profits from the shared revenue. In this case, there also exists a Pareto zone (i.e., the L zone) to achieve a win–win situation, as shown in

Figure 3a,b.