Rethinking Picky Shoppers and Store Reputation: Effective Online Service Recovery Strategies for Products with Minor Defects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Initiation of Monetary Compensation in Service Recovery

2.2. Apology Sincerity in Service Recovery

2.3. The Constructive Side of Consumer Pickiness

2.4. E-Store Reputation as Expectation and Pressure

3. Methods

3.1. Study 1

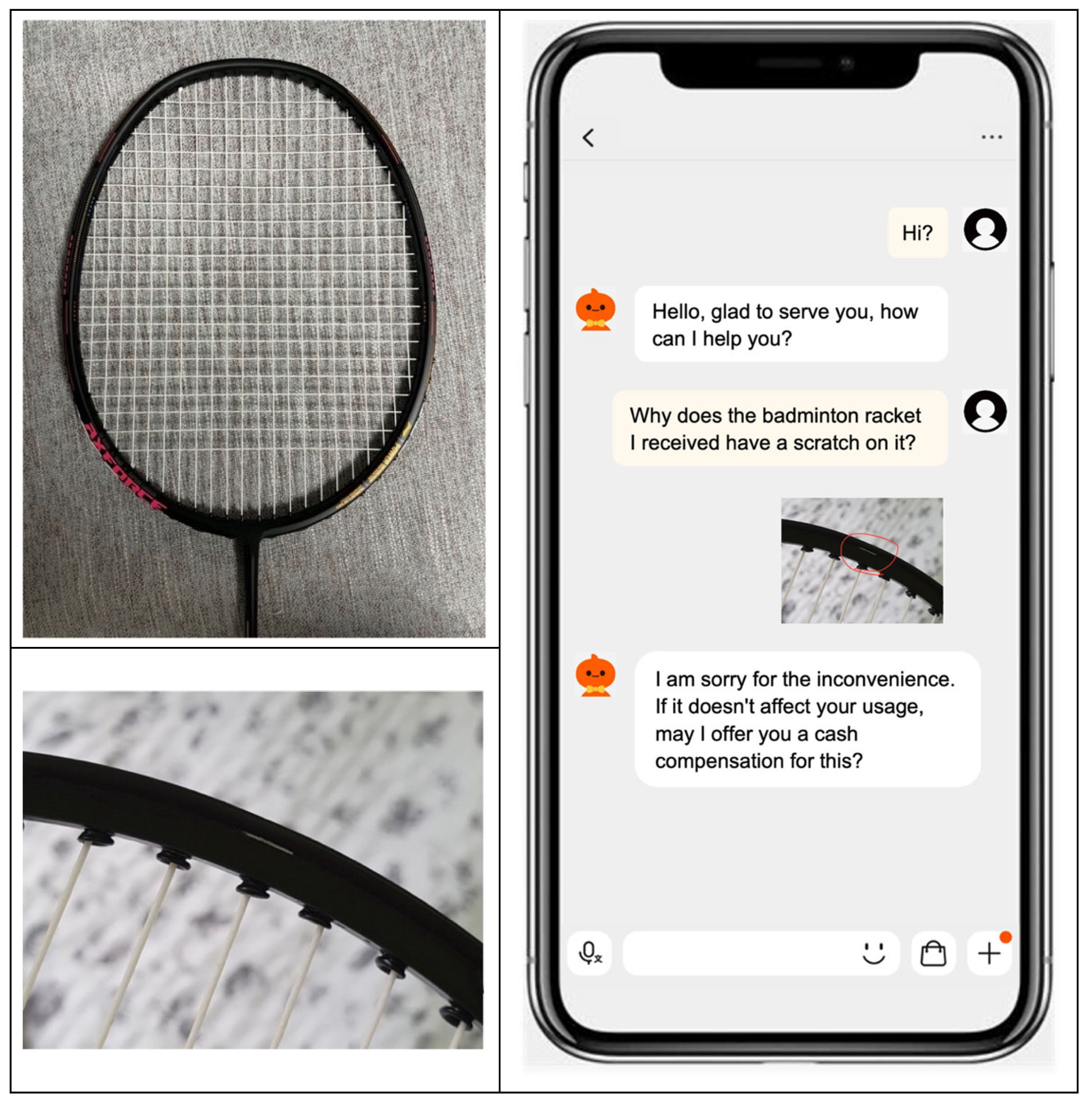

3.1.1. Design and Participants

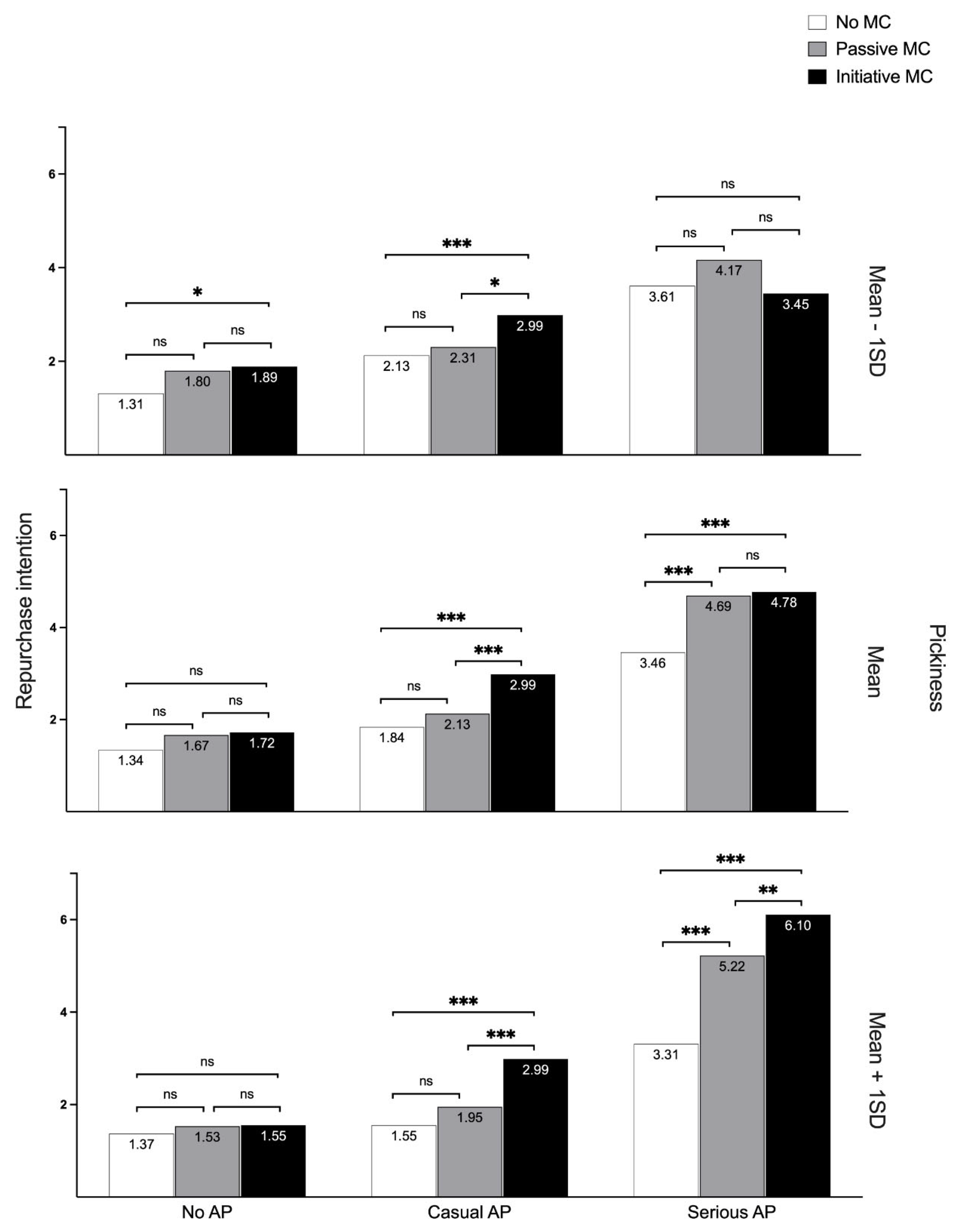

3.1.2. Results

3.1.3. Discussion

3.2. Study 2

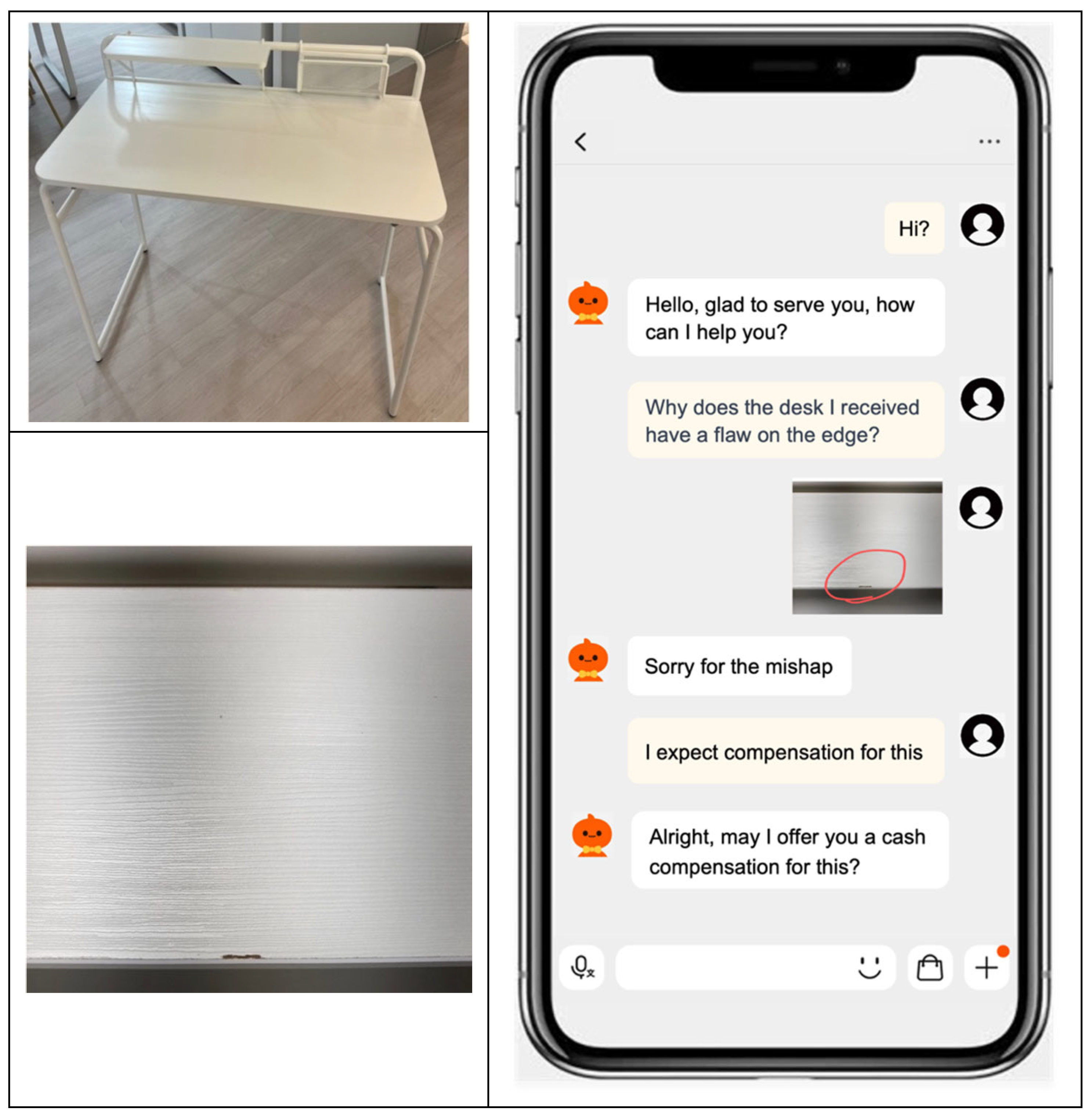

3.2.1. Design and Participants

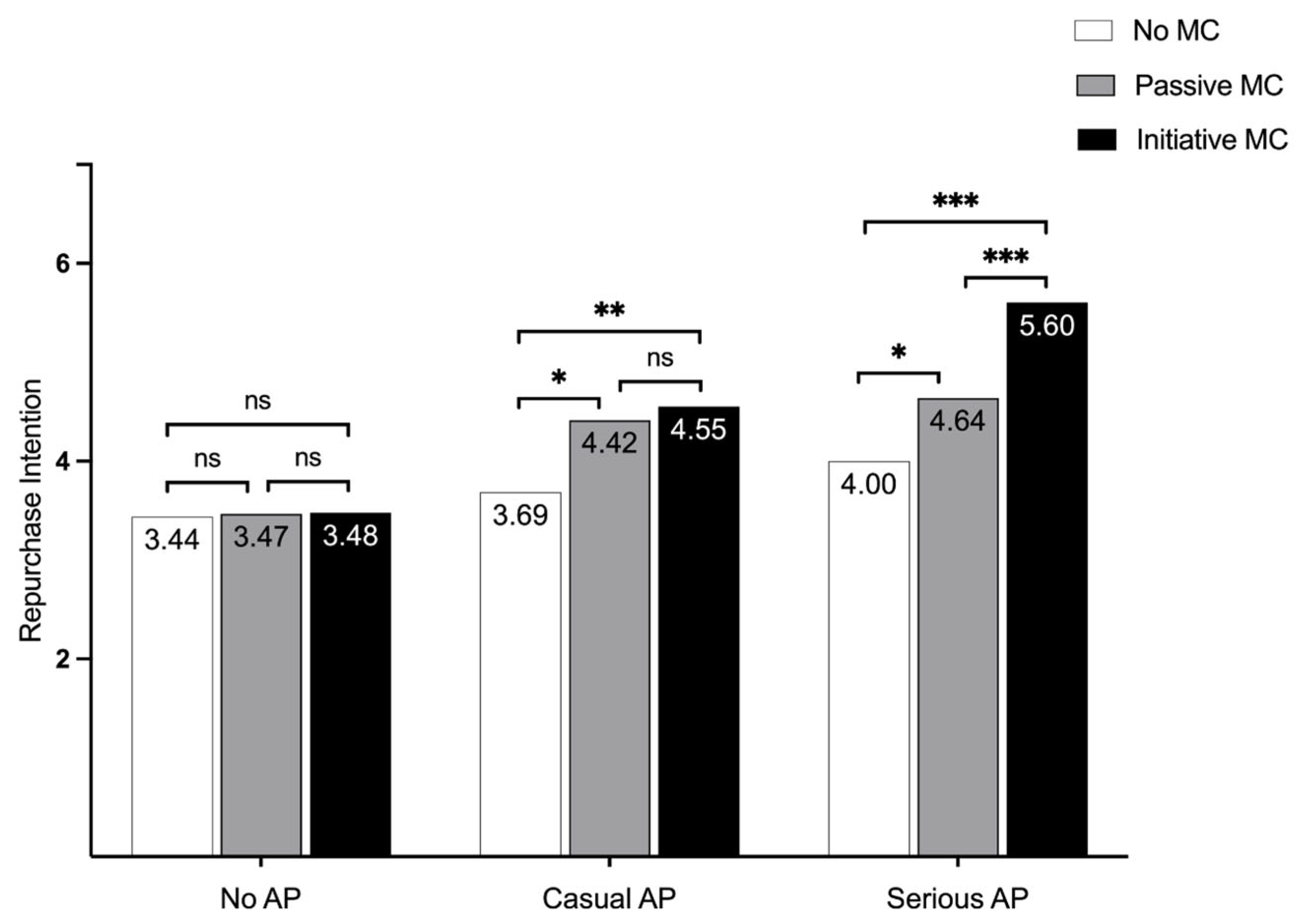

3.2.2. Results

3.2.3. Discussion

4. General Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Practical Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Source | Measures | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Study 2 | ||

| Catenazzo and Paulssen [9] | Perceived severity (1 = “Minor annoyance”, 5 = “So severe”) | 2.28 (1.01) | 2.68 (1.10) |

| 1. How severe is the problem of this product defect? | |||

| Patterson, et al. [36] | Monetary compensation initiation (1 = “Strongly disagree”, 7 = “Strongly agree”) | 3.13 (2.22) | 4.27 (1.89) |

| 1. I agree that the online customer service initiated the monetary compensation. | |||

| Ketron and Naletelich [65] | Perceived apology sincerity (1 = “Strongly disagree”, 7 = “Strongly agree”) | 3.17 (2.00) | 4.19 (1.59) |

| 1. This online customer service sincerely apologized for the incident. | |||

| 2. This online customer service was truly sorry for the harm or ill-will caused to me. | |||

| Ponzi, et al. [67] | E-store reputation (1 = “Strongly disagree”, 7 = “Strongly agree”) | 4.31 (1.55) | |

| 1. Based on the star rating of this e-store, the service quality of this e-store is high-quality and reliable. | |||

| 2. Based on the star rating of this e-store, this e-store has a good reputation. | |||

| Ma and Zhong [10] | Repurchase intention (1 = “Strongly disagree”, 7 = “Strongly agree”) | 2.85 (1.70) | 4.14 (1.59) |

| 1. I may still buy from this e-store in the future. | |||

| 2. I would probably buy from this e-store in the future. | |||

| Cheng, et al. [27] | Pickiness (1 = “does not describe me at all”, 7 = “describes me very well”). | 4.97 (0.89) | |

| 1. I have an extremely vivid idea of product attributes I seek. | |||

| 2. I go into stores with specific requirements in mind. | |||

| 3. I have rigid requirements that I won’t compromise on. | |||

| 4. I have very precise and particular attribute criteria. | |||

| 5. I dwell upon features I don’t like in potential purchases. | |||

| 6. It is hard for me to ignore even the tiniest negative features. | |||

| 7. I notice product “flaws” without deliberately looking for them. | |||

| 8. I find little things to nit-pick about when making purchases. | |||

| Experiment | Hypotheses Tested | Design | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (n = 330) | H1, H2, H3 | 3 (monetary compensation: initiative vs. passive vs. no) × 3 (apology: serious vs. casual vs. no) between-subjects design | Badminton racket |

| Study 2 (n = 537) | H1, H2, H4 | 3 (monetary compensation: initiative vs. passive vs. no) × 3 (apology: serious vs. casual vs. no) × 2 (e-store reputation: high vs. low) between-subjects design | Desk |

| Study | Variables | Groups (Mean) | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perceived severity | Badminton racket scratch (2.28) vs. midpoint (3.00) | p < 0.001 (t-test) |

| Initiation of monetary compensation | Initiative (5.62) vs. passive (2.30) vs. no (1.50) | all ps < 0.001 (ANOVA) | |

| Apology sincerity | Serious (5.46) vs. casual (2.29) vs. no (1.77) | all ps < 0.001 (ANOVA) | |

| 2 | Perceived severity | Minor desk nick (2.68) vs. midpoint (3.00) | p < 0.001 (t-test) |

| Initiation of monetary compensation | Initiative (5.22) vs. passive (4.72) vs. no (2.85) | all ps < 0.01 (ANOVA) | |

| Apology sincerity | Serious (4.79) vs. casual (4.39) vs. no (3.39) | all ps < 0.05 (ANOVA) | |

| E-store reputation | High (4.69) vs. low (3.93) | p < 0.001 (t-test) |

References

- Forbes, L.P.; Kelley, S.W.; Hoffman, K.D. Typologies of e-commerce retail failures and recovery strategies. J. Serv. Mark. 2005, 19, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.Y.; Seock, Y.-K. Effect of service recovery on customers’ perceived justice, satisfaction, and word-of-mouth intentions on online shopping websites. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeler, J.; Calaki, J.; Andree, K.; Basek, C. The power of apology. Econ. Lett. 2010, 107, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.Y. The role of culture in the perception of service recovery. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzutti, C.; Fernandes, D. Effect of recovery efforts on consumer trust and loyalty in e-tail: A contingency model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2010, 14, 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; He, Z.; He, S. Detecting and prioritizing product defects using social media data and the two-phased QFD method. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 177, 109031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Jiang, M.; Li, Y.N.; Li, W.; Mead, J.A. The impact of product defect severity and product attachment on consumer negative emotions. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 1026–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weun, S.; Beatty, S.E.; Jones, M.A. The impact of service failure severity on service recovery evaluations andpost-recovery relationships. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenazzo, G.; Paulssen, M. Experiencing defects: The moderating role of severity and warranty coverage on quality perceptions. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2023, 40, 2205–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Zhong, X. Moral judgment and perceived justice in service recovery. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 574–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, V.; Vijay, T.S.; Srivastava, A. The distinctive agenda of service failure recovery in e-tailing: Criticality of logistical/non-logistical service failure typologies and e-tailing ethics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Lin, X. Research on the influence of compensation methods and customer sentiment on service recovery effect. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2022, 33, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frable, F. Know before you click the risks of online buying. Nation’s Restaur. News 2013, 47, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Mantrala, M.K. Flawed products: Consumer responses and marketer strategies. J. Consum. Mark. 1985, 2, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerath, K.; Ren, Q. Consumer search and product returns. Mark. Sci. 2025, 44, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.K.X.; Bowden, J.L.-H. Negative customer engagement behaviour in a service context. Serv. Ind. J. 2025, 45, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameeni, M.S.; Ahmad, W.; Filieri, R. Brand betrayal, post-purchase regret, and consumer responses to hedonic versus utilitarian products: The moderating role of betrayal discovery mode. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, X. Functional or financial remedies? The effectiveness of recovery strategies after a data breach. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2024, 37, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, T.A.; Saleh, M.T.; Rabie, M.H.; Alhaj, G.M.; Khrais, L.T.; Mekebbaty, M.M.E. Investigating the effectiveness of monetary vs. non-monetary compensation on customer repatronage intentions in double deviation. Cent. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 30, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zheng, Q. Customer’s Evaluation Process of Service Recovery in Online Retailing. In Proceedings of the 2006 International Conference on Management Science and Engineering, Lille, France, 5–7 October 2006; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jafarzadeh, H.; Tafti, M.; Intezari, A.; Sohrabi, B. All’s well that ends well: Effective recovery from failures during the delivery phase of e-retailing process. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, U.; Israr, T.; Khan, Z. Service Recovery Strategies in Service Industry Affecting Consumer Forgiveness and Repurchase Intentions: Moderating Role of Online Brand Community Engagement. UW J. Manag. Sci. 2022, 6, 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, Z.; Hou, Z.; Meng, Y. The influence of empathy and consumer forgiveness on the service recovery effect of online shopping. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 842207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, Y. Effect of service recovery on recovery satisfaction and behavior intention: An empirical study on clothing product online shopping. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 10–13 December 2017; pp. 2236–2240. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu, P.; Li, Z.; Mensah, I.A.; Omari-Sasu, A.Y. Consumer response to E-commerce service failure: Leveraging repurchase intentions through strategic recovery policies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Meloy, M.G.; Polman, E. Picking gifts for picky people. J. Retail. 2021, 97, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A.; Baumgartner, H.; Meloy, M.G. Identifying picky shoppers: Who they are and how to spot them. J. Consum. Psychol. 2021, 31, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, G.; Hempelmann, B. Impacts of reputation for quality on perceptions of company responsibility and product-related dangers in times of product-recall and public complaints crises: Results from an empirical investigation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 13, 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Tippins, M.J. Consumer Attributions of Product Failure to Channel Members and Self: The Impacts of Situational Cues. Adv. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B.R. Service Promises Problems and Retrieval: A Research Agenda; Manchester School of Management: Manchester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mazhar, M.; Ting, D.H.; Hussain, A.; Nadeem, M.A.; Ali, M.A.; Tariq, U. The role of service recovery in post-purchase consumer behavior During COVID-19: A Malaysian perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 786603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roschk, H.; Gelbrich, K. Compensation revisited: A social resource theory perspective on offering a monetary resource after a service failure. J. Serv. Res. 2017, 20, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Peng, S. How to repair customer trust after negative publicity: The roles of competence, integrity, benevolence, and forgiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardley, M. Service recovery in unaffected consumers: Evidence of a recovery paradox. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2022, 14, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, S.W.; Hoffman, K.D.; Davis, M.A. A typology of retail failures and recoveries. J. Retail. 1993, 69, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.G.; Cowley, E.; Prasongsukarn, K. Service failure recovery: The moderating impact of individual-level cultural value orientation on perceptions of justice. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challagalla, G.; Venkatesh, R.; Kohli, A.K. Proactive postsales service: When and why does it pay off? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolon, S.; Quaiser, B.; Wieseke, J. Don’t try harder: Using customer inoculation to build resistance against service failures. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Ye, Q. First step in social media: Measuring the influence of online management responses on customer satisfaction. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, K.S.; Cheshire, C.; Rice, E.R.; Nakagawa, S. Social exchange theory. In Handbook of Social Psychology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casidy, R.; Shin, H. The effects of harm directions and service recovery strategies on customer forgiveness and negative word-of-mouth intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 27, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Booms, B.H.; Tetreault, M.S. The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, N.; Gwinner, K.P. Why don’t some people complain? A cognitive-emotive process model of consumer complaint behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 26, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsubo, Y.; Higuchi, M. Apology cost is more strongly associated with perceived sincerity than forgiveness. Lett. Evol. Behav. Sci. 2022, 13, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, I. Evaluations of Apologies: The Effects of Apology Sincerity and Acceptance Motivation. Doctoral Dissertation, Marshall University, Huntington, WV, USA, 2010. Available online: https://mds.marshall.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?httpsredir=1&article=1630&context=etd (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Risen, J.L.; Gilovich, T. Target and observer differences in the acceptance of questionable apologies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Chung, W. Analysis of the interactive relationship between apology and product involvement in crisis communication: An experimental study on the Toyota recall crisis. J. Bus. Tech. Commun. 2013, 27, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struthers, C.W.; Eaton, J.; Santelli, A.G.; Uchiyama, M.; Shirvani, N. The effects of attributions of intent and apology on forgiveness: When saying sorry may not help the story. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 44, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Okimoto, T.G.; Hornsey, M.J.; Lawrence-Wood, E.; Coughlin, A.-M. The mandate of the collective: Apology representativeness determines perceived sincerity and forgiveness in intergroup contexts. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017, 43, 758–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyrah, B.; Galoni, C.; Wang, J. Privileged and Picky: How a Sense of Disadvantage or Advantage Influences Consumer Pickiness Through Psychological Entitlement. J. Consum. Res. 2025, ucaf010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locander, W.B.; Hermann, P.W. The Effect of Self-Confidence and Anxiety on Information Seeking in Consumer Risk Reduction. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoplock, L.B.; Stinson, D.A.; Marigold, D.C.; Fisher, A.N. Self-esteem, epistemic needs, and responses to social feedback. Self Identity 2019, 18, 467–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Adwan, A.S.; Alrousan, M.K.; Yaseen, H.; Alkufahy, A.M.; Alsoud, M. Boosting online purchase intention in high-uncertainty-avoidance societies: A signaling theory approach. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ning, X. Uncertainty in the platform market: The information asymmetry perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 148, 107918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A. Surcharges and seller reputation. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Gregor, S.; Shen, Q.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, W.; Riaz, A. The power of emotions in online decision making: A study of seller reputation using fMRI. Decis. Support Syst. 2020, 131, 113247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Burke, R.R. Expectation processes in satisfaction formation: A field study. J. Serv. Res. 1999, 1, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Deokar, A.; Lee, H.C.B.; Summerfield, N. The role of commitment in online reputation systems: An empirical study of express delivery promise in an E-commerce platform. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 176, 114061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S.C. Reputation and uncertainty in online markets: An experimental study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Fox, G.L.; Roehm, M.L. Strategies to offset performance failures: The role of brand equity. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarel, D.; Marmorstein, H. Managing the delayed service encounter: The role of employee action and customer prior experience. J. Serv. Mark. 1998, 12, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanVoorhis, C.W.; Morgan, B.L. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ma, K.; Bian, X.; Zheng, C.; Devlin, J. Is high recovery more effective than expected recovery in addressing service failure?—A moral judgment perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Fung, J.W.; Won, I.; Huang, C.-M. Owning mistakes sincerely: Strategies for mitigating AI errors. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 29 April–5 May 2022; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ketron, S.; Naletelich, K. How anthropomorphic cues affect reactions to service delays. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 34, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ponzi, L.J.; Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A. RepTrak™ pulse: Conceptualizing and validating a short-form measure of corporate reputation. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2011, 14, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Wong, K.H.; Wang, J.W.; Cho, F.J. The effects of response strategies and severity of failure on consumer attribution with regard to negative word-of-mouth. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 71, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Online Service Failure Type | More Effective Strategy | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fan and Zheng [20] | Slow delivery | Compensation | Compensation boosts repurchase after service failures. Apologies alone do not suffice for satisfaction. |

| Jung and Seock [2] | Slow delivery and poor communication | Apology | Apologies enhance perceived fairness and interactional justice, with or without compensation. |

| Jafarzadeh et al. [21] | Packaging errors | Compensation | Economic compensation is most effective, signaling a high recovery effort. |

| Ma and Zhong [10] | Inferior product | Apology | Unethical service failures prompt a preference for apologies; ethical services benefit from both. |

| Wei and Lin [12] | Obvious product quality | Apology | Apologies outperform compensation in fostering positive emotions and diminishing negative ones. |

| Wei et al. [23] | Wrong and used product | Apology | Both compensation and apologies promote forgiveness; apologies do so more effectively. |

| Noor et al. [22] | Product falls below expectation | Compensation | The impact of compensation on the willingness to purchase is significant, whereas the impact of apologies is not. |

| Roy et al. [11] | Logistical issues | Compensation | Apologies alone are not effective in establishing justice to achieve service recovery. |

| Azizi et al. [19] | Unknown extra fees | Apology and compensation | Combining apology and compensation has the greatest impact on repatronage intentions. |

| Items | Value | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 (n = 330) | Study 2 (n = 537) | ||

| Gender | Male | 48.5 | 47.1 |

| Female | 51.5 | 52.9 | |

| Age | 18–20 | 9.7 | 4.7 |

| 20 s | 20.0 | 28.5 | |

| 30 s | 43.6 | 43.4 | |

| 40 s | 22.7 | 20.5 | |

| >50 | 3.9 | 3.0 | |

| Education | Below high school | 1.5 | 3.2 |

| High school degree | 26.1 | 9.7 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 60.3 | 61.3 | |

| Master’s degree and above | 12.1 | 25.9 | |

| Monthly income (RMB) | <1000 | 9.7 | 0.9 |

| 1001–3000 | 1.8 | 3.7 | |

| 3001–5000 | 32.1 | 20.3 | |

| 5001–10,000 | 42.7 | 48.0 | |

| >10,000 | 13.6 | 27.0 | |

| Antecedent | Repurchase Intention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | t-Value | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Constant *** | 1.34 | 0.16 | 8.61 | 1.04 | 1.65 |

| X1 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 1.50 | −0.10 | 0.74 |

| X2 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 1.77 | −0.04 | 0.80 |

| W1 * | 0.50 | 0.21 | 2.32 | 0.08 | 0.92 |

| W2 *** | 2.12 | 0.21 | 9.90 | 1.70 | 2.54 |

| X1 × W1 | −0.03 | 0.30 | −0.11 | −0.63 | 0.56 |

| X1 × W2 ** | 0.91 | 0.30 | 3.05 | 0.32 | 1.50 |

| X2 × W1 * | 0.77 | 0.30 | 2.57 | 0.18 | 1.36 |

| X2 × W2* | 0.94 | 0.37 | 2.52 | 0.20 | 1.67 |

| Pickiness | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.22 | −0.26 | 0.32 |

| X1 × pickiness | −0.19 | 0.23 | −0.80 | −0.64 | 0.27 |

| X2 × pickiness | −0.22 | 0.22 | −1.03 | −0.65 | 0.20 |

| W1 × pickiness | −0.36 | 0.19 | −1.88 | −0.73 | 0.02 |

| W2 × pickiness | −0.20 | 0.24 | −0.85 | −0.67 | 0.26 |

| X1 × W1 × pickiness | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.91 | −0.36 | 0.97 |

| X1 × W2 × pickiness * | 0.94 | 0.37 | 2.56 | 0.22 | 1.67 |

| X2 × W1 × pickiness | 0.54 | 0.30 | 1.83 | −0.04 | 1.13 |

| X2 × W2 × pickiness *** | 1.88 | 0.46 | 4.09 | 0.98 | 2.78 |

| Model summary | R2 = 0.75 | ||||

| F (17, 312) = 55.64 *** | |||||

| Pickiness | F | df1 | df2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean − 1SD = −0.89 | 1.10 | 4 | 312 | 0.36 |

| Mean = 0 | 5.53 | 4 | 312 | 0.00 |

| Mean + 1SD = 0.89 | 10.70 | 4 | 312 | 0.00 |

| Antecedent | Repurchase Intention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | t-Value | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Constant *** | 3.57 | 0.61 | 5.88 | 2.38 | 4.76 |

| X1 | 0.20 | 0.84 | 0.24 | −1.45 | 1.85 |

| X2 | 0.08 | 0.84 | 0.10 | −1.57 | 1.73 |

| W1 | −1.16 | 0.85 | −1.36 | −2.82 | 0.51 |

| W2 | 0.98 | 0.84 | 1.16 | −0.68 | 2.63 |

| X1 × W1 | 1.99 | 1.20 | 1.67 | −0.36 | 4.34 |

| X1 × W2 | −0.53 | 1.18 | −0.45 | −2.84 | 1.79 |

| X2 × W1 ** | 3.46 | 1.18 | 2.92 | 1.13 | 5.78 |

| X2 × W2 * | 0.47 | 1.18 | 0.39 | −1.86 | 2.79 |

| Reputation | −0.09 | 0.38 | −0.22 | −0.84 | 0.66 |

| X1 × reputation | −0.12 | 0.53 | −0.22 | −1.16 | 0.93 |

| X2 × reputation | −0.03 | 0.53 | −0.06 | −1.07 | 1.01 |

| W1 × reputation | 0.94 | 0.54 | 1.75 | −0.11 | 1.99 |

| W2 × reputation | −0.28 | 0.53 | −0.52 | −1.32 | 0.77 |

| X1 × W1 × reputation | −0.86 | 0.75 | −1.14 | −2.34 | 0.62 |

| X1 × W2 × reputation | 0.76 | 0.75 | 1.02 | −0.71 | 2.23 |

| X2 × W1 × reputation * | −1.76 | 0.75 | −2.34 | −3.23 | −0.29 |

| X2 × W2 × reputation | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.98 | −0.74 | 2.20 |

| Model summary | R2 = 0.21 | ||||

| F (17, 519) = 7.96 *** | |||||

| Reputation | F | df1 | df2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 3.22 | 4 | 519 | 0.01 |

| High | 4.73 | 4 | 519 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, X.; Nam, I. Rethinking Picky Shoppers and Store Reputation: Effective Online Service Recovery Strategies for Products with Minor Defects. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040259

Cheng X, Nam I. Rethinking Picky Shoppers and Store Reputation: Effective Online Service Recovery Strategies for Products with Minor Defects. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040259

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Xiaolian, and Inwoo Nam. 2025. "Rethinking Picky Shoppers and Store Reputation: Effective Online Service Recovery Strategies for Products with Minor Defects" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040259

APA StyleCheng, X., & Nam, I. (2025). Rethinking Picky Shoppers and Store Reputation: Effective Online Service Recovery Strategies for Products with Minor Defects. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040259