Abstract

As virtual influencers gain popularity, understanding the factors driving consumer responses is essential. However, limited research explores how perceived value (informativeness, entertainment, novelty, and incentives) and consumer engagement influence purchase intention. Perceived value is a key predictor of consumer behavior, while consumer engagement enhances perceived value and marketing effectiveness. Additionally, the moderating roles of source credibility and generational cohort remain underexplored. This study examines these relationships through a survey of 331 Chinese Generation Y and Z consumers, analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM). The results show that informativeness, entertainment, and incentives positively influence purchase intention, while novelty has a negative effect. Consumer engagement drives purchase intention and enhances perceived value. Source credibility and generational cohort moderate these effects. When source credibility is low, novelty reduces purchase intention, while incentives increase it. High source credibility makes consumer engagement more influential. Informativeness enhances purchase intention among Generation Y, whereas Generation Z is more influenced by consumer engagement. This study extends research on advertising value and consumer engagement, offering insights for brands optimizing virtual influencer marketing strategies across different consumer segments.

1. Introduction

Recently, virtual influencers—virtual characters produced by human or AI design and presented in the first person—have gained popularity in digital marketing [1]. In 2024, the global market for virtual influencers was estimated at USD 6.33 billion. It is projected to expand significantly, reaching USD 8.30 billion in 2025 and soaring to approximately USD 111.78 billion by 2033. This growth reflects a robust compound annual growth rate of 38.4% throughout the 2025–2033 period [2]. Virtual influencers, like human influencers, create positive content to draw attention to services and products on social media, thereby enhancing consumer engagement and marketing efficacy [3]. However, compared to human influencers, virtual influencers often drive higher engagement, but their lack of authenticity can result in lower purchase intentions for sponsored products [4].

Existing research on virtual influencer marketing can be divided into three categories: influencer, message, and user [5]. From the message perspective, studies have focused on content strategies to enhance consumer engagement, such as the effects of sponsorship disclosure [6], content format [7], and emotional expressions [8] on consumer engagement. From an influencer perspective, research has compared the endorsement effects of virtual and human influencers [6,9] and explored how the degree of realism influences these outcomes [10]. From a user perspective, studies have examined the impact of individual differences, such as regulatory focus [9], on consumer engagement (sharing) and purchase intentions in response to virtual influencers’ posts.

While prior studies have explored various aspects of virtual influencer marketing effectiveness, a thorough review reveals several critical gaps that still warrant further exploration. First, the contribution of consumer engagement to shaping purchase intentions and perceived value in virtual influencer marketing remains underexplored. Within the social media landscape, studies on consumer engagement have predominantly centered around browsing, liking, commenting, and sharing [11]. Consumer engagement fosters interactive experiences that enhance perceived value [12] and amplifies the word-of-mouth effect in marketing effectiveness and promoting brand loyalty [13]. However, limited research has investigated its impact on purchase intentions [14] or consumer perceptions [15], particularly its effect on perceived value, a well-established driver of user responses to marketing communications [16].

In the virtual influencer domain, while factors affecting consumer engagement with virtual influencers have been explored [17], the effect of engagement on purchase intentions and perceived value remains underexplored. Notably, engagement rates for virtual influencers are more than three times greater than those of human influencers [18]. Examining how such engagement shapes purchase intentions and perceived value is essential.

Second, limited attention has been given to how the perceived value of sponsored posts influences purchase intention. Perceived value is a key factor in forecasting consumer purchasing behavior [19]. While perceived message value has been explored within the domain of human influencers [20], there has been little research examining how it shapes purchase intentions for items advertised by virtual influencers.

Furthermore, the moderation of source credibility has been underexplored. While studies have established that source credibility can moderate and interact with other variables in diverse contexts [21,22], research on purchase intentions for items promoted by influencers has concentrated on its direct impact [23], leaving a gap in understanding its moderating influence.

Finally, individual differences in virtual influencer marketing remain underexplored. While personal differences, such as familiarity [24], can moderate responses to virtual influencers, research has largely neglected these factors [20]. In particular, Generation Z (Gen Z, born 1996–2011) and Generation Y (Gen Y, born 1980–1995) [25,26] have different perceptions of virtual influencers, and these generational differences are shaped by cultural context [27]. However, the moderating effects of generational differences within the Chinese cultural context have been rarely studied.

Given these gaps, a quantitative approach is employed to explore how consumers’ engagement with virtual influencer posts, along with the perceived value of these posts, influences purchase intentions. It also explores the moderation of source credibility and generational cohort.

The article follows this structure: It begins with an introduction that provides background context, followed by a literature review and hypothesis development. Next, the methodology covers sampling, data gathering, and measurement. Data processing and conclusions follow, including sample description, common method variance, scale validation, and hypothesis testing. The discussion section interprets the findings and highlights contributions to academic theory and practical use. Ultimately, the article concludes by addressing its limitations and proposing potential avenues for future investigation.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Consumer Engagement and Purchase Intentions

Consumer engagement refers to an individual’s involvement with an organization’s activities, which can be initiated either by the consumer or the organization itself. Consumer engagement is conceptualized by some researchers as a multidimensional construct involving cognitive (e.g., reading, thinking, and interest), emotional (e.g., a sense of belonging and attachment), and behavioral (e.g., commenting, liking, and interacting) dimensions [28], while others focus on a single dimension, such as the number of comments [8]. In this study, consumer engagement is defined as users’ behavioral interactions with posts created by virtual influencers, including browsing, liking, commenting, and sharing. Specifically, the behavioral dimension of engagement is emphasized.

Prior studies have demonstrated that consumer engagement with content posted by human influencers positively influences purchase intentions for the products featured in those posts [29]. Virtual influencers are distinct due to their controlled, non-human nature [4]. Even with curated personas, virtual influencers may evoke similar reactions to human influencers, but with different strengths [6,9]. Therefore, engagement with virtual influencers’ posts may still positively affect purchase intentions, albeit to a different degree compared to human influencers. Thus, the hypothesis below is presented:

H1:

Consumer engagement with posts created by virtual influencers boosts purchase intentions for items highlighted in the posts.

2.2. Effects of Consumer Engagement on Perceived Value

Consumers’ prior experiences significantly shape their perceptions of marketing messages [30]. In particular, experiences derived from participation in marketing activities contribute to more favorable perceptions of those activities [31]. Increased consumer engagement with a brand, which enhances consumers’ overall experience, tends to lead to more positive perceptions of that brand [32]. Among the various perceptions consumers form, the perceived value of marketing messages is a significant predictor of their behavior [19].

When examining the perceived value of social media content, researchers frequently reference Ducoffe’s ad value model [33], which defines ad value as the consumer’s subjective assessment of an ad’s worth or utility [16]. Based on this model, informativeness, entertainment, and irritation are crucial variables influencing ad value, with informativeness and entertainment enhancing ad value, while irritation diminishes it [16]. Subsequent studies have extended this model [16] by incorporating variables such as credibility in internet ad value [33] and incentives in mobile ad value [34].

Ducoffe’s ad value model [16] has been applied to evaluate the perceived value of sponsored content from social media influencers [20]. Based on this, this study defines the perceived value of virtual influencers’ posts as the users’ subjective assessment of their worth or usefulness. In terms of its dimensions, this study draws on interview findings and, based on Ducoffe’s model (1996) and its extensions, identifies these dimensions as informativeness, entertainment, and incentives [16]. Furthermore, given that consumers view virtual influencers as novel entities [4] and considering that novelty has also been recognized as a key driver of perceived value in other fields [35], this study incorporates novelty as an additional dimension of perceived value.

Informativeness refers to an ad’s capacity to inform customers about product alternatives, enhancing customer satisfaction [16]. Correspondingly, perceived informativeness refers to the extent to which consumers believe that virtual influencers’ posts can provide product information that enhances their satisfaction. During live-stream interactions, consumer engagement helps users gain product information [36]. Furthermore, greater engagement with the content shared by peers results in a heightened perception of its informational value [14]. Therefore, this study posits that user engagement with virtual influencers’ posts can enhance their perceived informational value. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2:

Consumer engagement with virtual influencers’ posts positively influences those posts’ perceived informativeness.

Entertainment refers to an ad’s ability to amuse consumers [16]. Therefore, perceived entertainment refers to the ability of virtual influencers’ posts to amuse consumers. Virtual influencers fulfill consumers’ diversion needs by providing enjoyment or escapism [37]. Previous research has shown that engaging with a brand’s content on social media enhances users’ perceptions of its social, entertainment, and functional value [38]. Therefore, in the context of virtual influencers, this study posits that increased consumer engagement with posts by virtual influencers can enhance their perception of the entertainment value of these posts. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3:

Consumer engagement with virtual influencers’ posts positively influences those posts’ perceived entertainment.

Novelty refers to how consumers perceive an item or experience as new or different [39]. The extent to which consumers perceive virtual influencers’ posts as new or different is referred to as perceived novelty. Although authenticity and reliability are often questioned, virtual characters are inherently more novel than their human counterparts [40]. Engagement with novel objects can enhance users’ perception of their novelty. For example, research has found that immersive VR, with its higher interactivity and engagement, allows users to experience the virtual environment more deeply. This interactivity and engagement, in turn, enhances users’ perception of the experience’s novelty [41]. Therefore, it can be inferred that the more users engage with virtual influencers’ posts, the more they will experience the novelty of those posts, thus enhancing their perception of novelty. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4:

Consumer engagement with virtual influencers’ posts positively influences those posts’ perceived novelty.

Incentives refer to the rewards users receive from posts, which can be monetary (e.g., discounts, gifts) or non-monetary (e.g., badges, honors). Perceived incentives reflect consumers’ perception of the rewards provided by virtual influencers’ posts. Research has shown that interactivity can enhance people’s cognitive processing of information [42]. As users interact with live streamers, this interactivity enhances immersion, which in turn boosts the perceived usefulness of live-stream e-commerce. Perceived usefulness is often reflected through the provision of promotional information, discounts, and other incentive-related content about the products [43].

Engagement is an interactive process that involves actions such as paying attention to, liking, and commenting on the information posted by virtual influencers. It can be inferred that as users engage with the posts of virtual influencers, their cognitive processing of the reward information within these posts is enhanced, thereby increasing their perception of the incentives. It is thus hypothesized that

H5:

Consumer engagement with virtual influencers’ posts positively influences those posts’ perceived incentives.

2.3. Effects of Perceived Value on Purchase Intention

Perceived value predicts purchase intentions [19], and this also holds for the perceived value of AI (artificial intelligence) marketing tools [44]. This study examines the perceived value from four dimensions: perceived informativeness, entertainment, novelty, and incentives. Among these, the informativeness of social media influencers’ posts can strengthen users’ trust and increase purchase intentions [20]. Regarding virtual influencers, they attract consumers by offering valuable information [4]. Additionally, consumers’ perceptions of virtual influencers’ informational power (i.e., the ability to provide useful information) can significantly influence their engagement with such content [45]. Therefore, this study proposes:

H6:

The perceived informativeness of posts by virtual influencers positively affects purchase intentions for products mentioned in those posts.

Another key dimension of perceived value is entertainment. Social media influencers often incorporate humor—a key factor in follower retention and persuasion—to entertain followers [46]. The entertainment value associated with virtual influencer endorsements can enhance user satisfaction [47] and increase purchase intentions for the recommended product [48]. Building on this, this study proposes the following:

H7:

The perceived entertainment of posts by virtual influencers positively affects purchase intentions for products mentioned in those posts.

Beyond informativeness and entertainment, the novelty of virtual influencer content plays a crucial role. Incorporating virtual influencers into advertising campaigns enhances the perceived novelty of the advertisements [49], and scholars have emphasized the significance of novelty in virtual influencer research [50]. The perceived novelty associated with virtual influencers can attract users to follow them [4] and increase engagement [51]. Although no studies have directly shown that the perceived novelty of virtual influencers’ posts enhances purchase intentions, research on personalized recommendation systems suggests that novelty can increase consumer satisfaction and purchasing intentions [52]. Therefore, this study suggests the following:

H8:

The perceived novelty of virtual influencers’ posts positively affects purchase intentions for products mentioned in those posts.

Finally, users prefer ads that offer incentives, and these rewards can directly affect their willingness to accept the ads [53]. Including reward-based content in social media posts may increase users’ engagement, such as liking and sharing behavior [54]. Monetary incentives can also motivate customers to leave more favorable product reviews [55] and comment more frequently on blog posts [56]. Consequently, this study proposes the following:

H9:

The perceived incentives provided by virtual influencers’ posts positively affect purchase intentions for products mentioned in those posts.

2.4. Mediation Effects of Perceived Value

Consumer engagement and its effects can be influenced by certain mediating variables [57]. Perceived value has been shown to serve as a mediator between consumer engagement and its outcomes. For example, perceived value, including entertainment value, mediates the relationship between consumer engagement and the consumer-brand relationship strength, meaning that consumer engagement can enhance the strength of the consumer-brand relationship by increasing perceived value [38]. In this study, the perceived value of virtual influencers’ posts includes perceived informativeness, entertainment, novelty, and incentives. Existing research has shown that, on one hand, consumer engagement can enhance perceptions of informational, entertainment, novelty, and other values [14,38], while, on the other hand, these perceived values can increase users’ purchase intentions [20,48]. Based on these findings, this study posits that the perceived value of virtual influencers’ posts—namely, informativeness, entertainment, novelty, and incentives—mediates the relationship between consumer engagement and purchase intentions. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H10:

The effect of consumer engagement on purchase intentions is mediated by perceived value, including informativeness (H10a), entertainment (H10b), novelty (H10c), and incentives (H10d).

2.5. The Moderation of Source Credibility

An information provider seen as both an expert and reliable is considered to possess source credibility [58]. The credibility of an endorser has been shown to influence how recipients form attitudes and behaviors toward the endorsed object [59,60]. In the case of virtual influencers, their source credibility can enhance users’ engagement with their posts and their intention to choose the products they recommend [61].

Source credibility plays a moderating role in various fields, such as the relationship between celebrity endorsements and consumer attitudes [22], the influence of review characteristics on consumer perceptions of products [62], and the connections among recommendation attributes, recommendation credibility, and adoption intentions [63]. Additionally, it moderates the link between climate information and perceived risk [21]. However, little research examines the moderation of source credibility in the relationships among consumer engagement, perceived value, and purchase intention in virtual influencer marketing. Thus, it is proposed: H11: Source credibility moderates the following:

- (1)

- The relationships between perceived value ((H11a) perceived informativeness, (H11b) perceived entertainment, (H11c) perceived novelty, and (H11d) perceived incentives) and purchase intention;

- (2)

- The relationships between consumer engagement and perceived value ((H11e) perceived informativeness, (H11f) perceived entertainment, (H11g) perceived novelty, and (H11h) perceived incentives);

- (3)

- The mediating effects of perceived value ((H11i) perceived informativeness, (H11j) perceived entertainment, (H11k) perceived novelty, and (H11l) perceived incentives) between consumer engagement and purchase intention.

2.6. The Moderation of Generational Cohort

It is suggested that the influence of consumers’ perceptions of influencers’ recommendations on purchase intentions differs across generational cohorts [64]. A generational cohort consists of individuals born in the same time frame, sharing common life experiences, and being influenced by distinct social, political, and economic circumstances [65]. Among the frequently referenced cohorts are Gen X, Gen Y, and Gen Z [66]. People born between 1980 and 1995 are typically categorized as Gen Y, while those born after 1995 are classified as Gen Z [25]. Gen Y tends to emphasize rational decision-making, whereas Gen Z places more value on enjoyment, learning, and adventure [67]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed: H12: Generational cohort moderates:

- (1)

- The relationships between perceived value ((12a) perceived informativeness, (12b) perceived entertainment, (12c) perceived novelty, and (12d) perceived incentives) and purchase intention;

- (2)

- The relationships between consumer engagement and perceived value ((12e) perceived informativeness, (12f) perceived entertainment, (12g) perceived novelty, and (12h) perceived incentives);

- (3)

- The mediating effects of perceived value ((12i) perceived informativeness, (12j) perceived entertainment, (12k) perceived novelty, and (12l) perceived incentives) between consumer engagement and purchase intention.

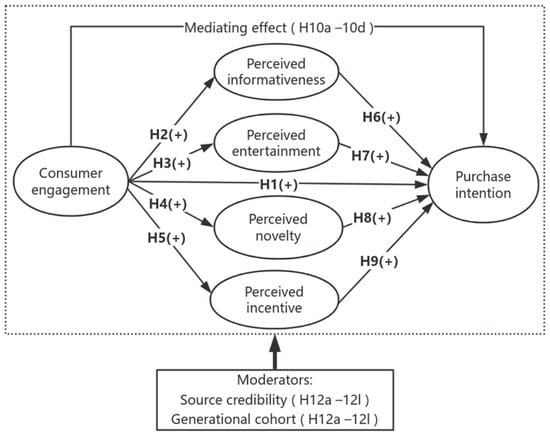

Figure 1 summarizes the model based on reviewed background and hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Gathering and Sampling

Two focus group interviews were conducted before the main survey. One group consisted of Gen Y participants, and the other of Gen Z, with eight individuals (four males, four females) in each group, all knowledgeable about virtual influencers. The focus groups provided valuable insights that refined the survey. The interviews revealed that participants preferred posts offering entertainment or novelty over purely promotional content, leading to the inclusion of hedonic value (entertainment) and uniqueness (novelty) in the perceived value scale. Additionally, some terms in the original scales, such as “informativeness” and “credibility,” were deemed ambiguous in the context of virtual influencers, prompting rewording for clarity.

Following the focus group discussions, a pilot test was conducted with 30 participants to evaluate the reliability of the measurement scales. The results showed that the scales demonstrated acceptable reliability, with factor loadings exceeding the 0.5 threshold, indicating good construct validity [68]. Based on these findings, a few items were adjusted for clarity, and redundant items were removed.

The main study utilized a web-based survey method to collect data. The questionnaires were distributed through Wenjuanxing (www.wjx.cn) with a simple random sampling method. Given the novelty of virtual influencers and the potential unfamiliarity of some participants with them, an introductory explanation was provided at the beginning of the survey. This ensured that only Gen Y and Gen Z participants with prior knowledge of virtual influencers were eligible to proceed. The validity of the data was ensured by including an attention-check question that instructed participants to select ‘strongly agree’ to confirm they had read the item carefully. Only those providing correct responses to this question were deemed valid.

To ensure sample representativeness, the survey was disseminated across multiple nationwide virtual communities on Weibo, Douyin, and Xiaohongshu, three major social media platforms in China. Data collection took place between 1 March 2024, and 30 May 2024, resulting in 400 responses. After excluding responses with excessively short completion times (less than two minutes), those with uniform answers, or those who failed the attention-check question, a final dataset of 331 valid responses was obtained, representing 82.8% of the total responses.

As indicated in Table 1, the final sample was made up of 52.3% males and 47.7% females. Among them, 52.9% were Gen Z, while 47.1% were Gen Y. Regarding educational background, approximately 84.5% of respondents held a college degree or higher. In terms of income distribution, 33.5% reported earning less than RMB 2000 (roughly USD 276), while 19.7% earned more than RMB 8000 (approximately USD 1100), with a relatively even distribution across income levels ranging from RMB 2000 to 8000 (USD 276–1100). Overall, the sample’s demographic composition generally reflects the characteristics of followers of virtual influencers in the Chinese market [69].

Table 1.

Demographics of the participants.

3.2. Measures

This study used measurement scales adapted from existing research. All items were rated using a seven-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. A three-item scale was used to measure purchase intention [70]. Scales for perceived informativeness and entertainment each comprised three items [33], while perceived novelty was evaluated by four items [71]. Perceived incentives were evaluated using three items [72]. A fourteen-item scale [73] was used to assess source credibility as the moderating variable. Based on the pretest results, two items with similar meanings were combined to enhance clarity and consistency in the Chinese translation. Appendix A provides a complete overview of the measurement scales.

4. Data Analysis and Results

For descriptive analyses, this study used SPSS 25.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). For Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and multi-group SEM to validate the measurement scales and hypotheses, AMOS 26.0 (Analysis of Moment Structures) was applied.

A traditional two-step SEM approach was adopted. The first step involved assessing the measurement model with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), including reliability and validity. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR)) were used to evaluate reliability. To assess validity, both convergent validity (via factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and discriminant validity (based on the Fornell–Larcker criterion) were examined. The second step involved the examination of the proposed hypotheses through testing the structural model. Goodness-of-fit indices were applied to assess the model fit, while the significance of the hypothesized paths was measured by analyzing the coefficient parameter estimates.

Further, to test mediation and moderated mediation effects, the SPSS PROCESS macro version 4.2 [74] was used with bootstrapping (5000 resamples).

4.1. Common Method Variance

When detecting potential common method variance (CMV), this study conducted Harman’s one-factor test [75]. The unrotated exploratory factor analysis on all measurement items showed that the first factor explained 25.95% of the total variance, well below the 50% threshold, indicating that CMV is not a significant concern.

4.2. Measurement Model

The measurement model has an acceptable fit [76], as indicated by the following parameters: CMIN = 493.229, df = 194, CMIN/df = 2.542, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.953, TLI = 0.944, and RMSEA = 0.066. Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha values range from 0.78 for entertainment to 0.90 for incentives, well above the generally accepted level of 0.7 [77], reflecting desirable internal consistency and reliability.

Each item’s standardized factor loading exceeds the threshold [68]. The CR values vary from 0.79 (entertainment) to 0.92 (consumer engagement), and the AVE values span from 0.53 (novelty) to 0.72 (purchase intentions), all meeting or surpassing the suggested thresholds of 0.7 for CR and 0.5 for AVE [78]. As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, the measurement model demonstrates satisfactory convergent validity.

Table 2.

Results of the confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 3.

Mean, standard deviation, convergent, and discriminant validity.

The Fornell and Larcker (1981) method was employed to assess discriminant validity, focusing on whether a variable’s AVE square root exceeds its interrelations with other constructs [78]. Each variable’s AVE (bold diagonal values) square root surpasses its correlations with other variables (Table 3), illustrating the acceptable discriminant validity of the measurement model.

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

AMOS26.0 was employed to evaluate the structural equation model, with the results indicating a good fit (CMIN = 524.433, df = 196, CMIN/df = 2.676, p < 0.001, TLI = 0.936, CFI = 0.946, RMSEA = 0.062). Table 4 presents the findings related to the direct effect of hypothesis testing.

Table 4.

SEM results—direct results.

Specifically, consumer engagement positively influences purchase intention, perceived informativeness, entertainment, novelty, and incentives, providing empirical support for H1 through H5. Meanwhile, perceived informativeness, entertainment, and incentives significantly impact purchase intentions, fully supporting H6, H7, and H10. However, while perceived novelty significantly affects purchase intentions, the effect is negative, contrary to the hypothesized direction, and H8 is rejected.

4.4. Mediation Analysis

The mediation analysis using SPSS 26.0 PROCESS Macro 4.1 (Model 6) revealed significant indirect effects for two of the four proposed mediators. Specifically, perceived informativeness and perceived incentives demonstrated partial mediation between consumer engagement and purchase intention, thus supporting H10a and H10d. No significant mediation effect was found for perceived entertainment and novelty, thus, H10b and H10c were not supported. The specific analysis results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results of the mediation analysis.

4.5. Measurement Invariance and Multi-Group Analysis

This study treated source credibility and generational cohort as grouping variables and conducted multi-group SEM to examine the indirect effect hypotheses. Participants were classified into high- and low-credibility groups using the mean value 4.93 for source credibility. Respondents with scores at or above 4.93 were assigned to the high-credibility group, while those below 4.93 were categorized as low-credibility. For the generational cohort, individuals born from 1980 to 1995 were identified as Gen Y, while those born from 1996 to 2011 were classified as Gen Z.

A multi-group CFA was performed to evaluate measurement invariance across different source credibility levels and generational cohorts. First, the baseline for subsequent comparisons was set using a configural invariance model. Then, the sequence of tests involved three levels of measurement invariance: metric invariance, scalar invariance, and residual invariance. Metric invariance was evaluated by fixing the factor loadings in the configural invariance model, scalar invariance was assessed by additionally constraining the intercepts in the metric invariance model, and residual invariance was tested by setting the measurement residuals equal across groups.

Measurement invariance was evaluated using variance difference tests (p > 0.01), changes in the Comparative Fit Index (|ΔCFI| < 0.010), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (|ΔRMSEA| < 0.015). All tests meet the specified criteria [79].

Multi-group SEM analyses indicate. that source credibility and generational cohort significantly influence the relationships within the model. To investigate these effects further, the coefficients of the specified pathways were compared across the two groups using critical ratio differences. A difference was considered significant when the critical ratio’s absolute value exceeded 1.96, corresponding to a significance level of 0.05 [80]. Path coefficient comparison results across groups are provided in Table 6.

Table 6.

Moderating effect summary.

Research revealed that source credibility moderates the relationships between perceived novelty, advertising incentives, consumer engagement, and purchase intention. Specifically, when a virtual influencer has low credibility, users tend to exhibit lower purchase intentions due to the novelty of the information they post, while the presence of advertising incentives increases their purchase intentions. However, neither novelty nor advertising incentives significantly impact the purchase intentions of users exposed to high-credibility influencers. Additionally, the positive relationship between consumer engagement and purchase intention is more pronounced when associated with high-credibility influencers. Therefore, H11 receives partial support.

Similarly, generational cohorts were found to moderate both the relationship of perceived informativeness to purchase intention and that of consumer engagement to purchase intention. Specifically, perceived informativeness enhances Gen Y’s purchase intention. However, this effect is not observed in Gen Z. Furthermore, consumer engagement has a significantly stronger effect on Gen Z’s purchase intention compared to Gen Y. Therefore, H12 is only partially supported.

The moderated mediation analysis using PROCESS Macro 4.1 (Model 7) revealed that perceived informativeness and incentives significantly mediated the relationship between consumer engagement and purchase intention for both Gen Y and Gen Z, as well as for virtual influencers with both high and low source credibility. Bootstrap 95% confidence intervals confirmed the significance of these mediation effects. The specific analysis results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results of the moderated mediation analysis.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion of the Results

The aim of this study is to analyze how consumer engagement and perceived value impact purchase intentions for products featured in sponsored posts by virtual influencers. The moderating effects of source credibility and generational cohort on these relationships are also explored. Data were collected from Gen Y and Gen Z participants in China who are acquainted with virtual influencers to address this objective. The analysis indicates that consumer engagement positively influences purchase intentions and enhances various perceived values, all aspects of perceived value—including perceived informativeness, entertainment, incentives, and novelty—affect purchase intentions, with informativeness, entertainment, and incentives having a positive impact and novelty having a negative effect. Moreover, certain relationships are moderated by source credibility and generational cohort.

For the effect of consumer engagement, the findings align with our hypotheses, indicating that consumer engagement is a significant predictor of purchase intention and also has a profound effect on consumers’ perceived value, particularly enhancing the perceived value of incentives. Prior research also shows that consumer engagement with online content can boost purchase intention. For example, interactions with peer-shared posts [14] and live-streamed commercial content [29] have both been found to increase purchase intention.

As for perceived value, this study also aligns with previous work demonstrating that consumer engagement enhances value perceptions [14,38], particularly regarding incentives. As consumer engagement increases, they become more knowledgeable about the brand and derive greater satisfaction [81]. Engagement with social media content influences value creation across hedonic, social, and functional dimensions [82]. Gen Y and Z, more inclined toward reward-based information [83], tend to pay greater attention to such content. Therefore, as their level of consumer engagement increases, they become more attuned to the rewards embedded in the information.

For the effect of perceived value on purchase intention, this study reveals that incentives affect purchase intention more than factors such as informativeness, entertainment, or novelty. This draws attention to the sustained importance of incentives in driving consumer behavior. Previous research has also identified incentive programs, such as membership cards, free trials, and coupons, as significant predictors of purchase intention [84]. This finding is particularly relevant for the younger participants in this study, as they prefer marketing strategies that offer discounts and rewards [83]. Their heightened responsiveness to incentive-driven content makes the influence of incentives even more pronounced in shaping their purchase decisions.

A noteworthy finding is the negative effect of novelty. This result contrasts prior research, which indicates that novelty positively influences purchase intention [85]. However, while past studies have found positive effects of novelty, these effects are generally limited. For instance, research has shown that ad creativity—similar to novelty—elicits more positive responses related to the ad (such as ad attitudes) than to the brand or purchase intentions. This effect is also weaker in mobile environments [86]. The reason could be that novelty, particularly in the context of products, may evoke feelings of uncertainty and perceived risk [87], which could lower purchase intention [88]. Similarly, the novelty introduced by virtual influencers may generate uncertainty and perceived risk [49], thereby reducing purchase intention.

For the moderation of source credibility, it operates as follows: to begin with, when the source credibility is low, the novelty of posts decreases purchase intention, while incentives increase it. However, these effects are insignificant when the influencer’s credibility is high. Novelty is often linked to increased risk and uncertainty [87], and source credibility can mitigate users’ risk perception [89]. In this case, low credibility heightens the risk perception, which may cause novelty to impact purchase intention negatively.

Furthermore, incentives are more likely to trigger purchase intention in low-credibility contexts, but this effect is diminished when the influencer’s credibility is high. This could be because the influence of source credibility outweighs that of incentives. Research has shown that source credibility substantially impacts perceived value more than rewards [90]. When source credibility is high, it may overshadow the impact of rewards, whereas, in a low-credibility context, rewards have a more noticeable effect. Similar findings have been reported, where lower source credibility leads users to be more influenced by the credibility of recommendations [63].

In addition, when the influencers have high credibility, consumer engagement is more likely to influence purchase intention positively. High credibility reduces perceived risk [89], making users more likely to engage and act on purchase intentions. Prior research has also found that environmental behaviors, such as climate-related actions, are only triggered in high-credibility contexts [21].

For the moderation of the generational cohort. It is revealed that Gen Y is more likely to base its purchase intention on the informativeness of posts, while Gen Z is more influenced by consumer engagement. A previous study also found that informativeness elicits a positive response to advertisements from Gen Y rather than Gen Z [91]. This difference likely stems from Gen Y consumers being more familiar with online shopping, encouraging information-seeking behaviors that enhance purchase intention [92]. In contrast, Gen Z has grown accustomed to interacting and communicating online [93]. As a result, they place greater emphasis on experiential engagement, resulting in higher purchase intentions. This finding aligns with prior research, which suggests that social interactions, such as attachment or immersion with influencers, are more likely to drive purchase intention in Gen Z [94].

5.2. Theoretical Implications

Theoretically, this paper makes several advancements. Initially, it is the first to investigate how consumer engagement operates. Unlike previous research that primarily promotes consumer engagement, this study delves into its subsequent effects, specifically on perceived value and purchase intention. It is revealed that consumer engagement influences purchase intention and enhances consumers’ perceived value. By elucidating how consumer engagement shapes consumer responses, this research enriches the theoretical perspective on consumer engagement and its implications in virtual influencer campaigns.

Second, this research investigates the impact of the message value in virtual influencers’ sponsored posts on purchase intentions. Through combining a literature review and in-depth interviews, this study identifies the perceived value dimensions of these posts—namely informativeness, entertainment, novelty, and incentives—and explores their relationships with purchase intentions, thereby extending Ducoffe’s (1996) ad value model [16] to virtual influencer marketing, while deepening insights into how informational elements in posts influence consumer behavior.

Third, this study examines the moderation of source credibility and generational differences. While prior research has largely overlooked how these factors shape the connections between perceived value, consumer engagement, and purchase intention, this study highlights that the source credibility of virtual influencers and generational cohorts moderate these associations. By identifying these moderating effects, this research provides greater insight into the marketing influence of virtual influencers and offers valuable implications for social media marketing strategies.

5.3. Practical Implications

First, careful consideration is needed regarding the impact of consumer engagement on brand-sponsored posts published by virtual influencers. These posts’ informativeness, entertainment, and incentives contribute to increased purchase intention, while novelty tends to decrease it. Consumer engagement has a direct impact on purchase intention and enhances the perceived value of the posts’ informativeness, entertainment, novelty, and incentives. Users with higher engagement levels are likelier to perceive greater informativeness, entertainment, and incentives, boosting purchase intention. Therefore, increasing consumer engagement is crucial. However, highly engaged users may also perceive novelty more strongly, which could lower purchase intention. Although many studies emphasize strategies to promote consumer engagement [8,17], misuse of these strategies may result in unintended consequences. Therefore, when targeting highly engaged users, it is important to minimize the novelty of the posts.

Second, the interaction between source credibility and perceived value should be considered in its impact on purchase intention. When low-credibility virtual influencers share incentive-based content, it enhances purchase intention, making them more suitable for delivering such messages. However, they should be cautious when promoting novelty-driven content, as it may decrease purchase intention. In contrast, high-credibility influencers do not drive purchase intention through incentive-based content, but consumer engagement with their posts can enhance purchase intention. Therefore, fostering consumer engagement is a more effective strategy for high-credibility influencers to boost purchase intention.

Third, market segmentation based on generational characteristics is necessary. This study finds that informativeness boosts purchase intention for Gen Y but has no significant effect on Gen Z. In contrast, consumer engagement exerts greater influence on Gen Z’s purchase intention than on Gen Y’s. Therefore, to enhance purchase intention, marketers should implement generation-specific strategies. For Gen Y, the focus should be on informational posts that provide timely, relevant, and high-quality product or brand information. For Gen Z, marketers should prioritize engagement drivers such as monetary incentives (e.g., coupons), psychological rewards (e.g., virtual badges), and social influence mechanisms (e.g., showcasing peer interactions).

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study employed a rigorous methodology, several limitations should be addressed in subsequent studies. To begin with, this study focused solely on two distinct groups (i.e., Gen Y and Gen Z) from China, potentially restricting its applicability. Research in the future should explore a wider sample that includes different generations and regions.

Second, subjectivity could have influenced the findings, as the data were collected using self-report scales. Combining subjective and objective methods would be beneficial to enhance the validity of future studies. For example, objective data collected from websites could quantify consumer engagement and enhance the reliability of the findings.

Third, this investigation employed a cross-sectional design, capturing participants’ perceptions and intentions at a single time. As technology evolves and people’s views on virtual influencers change, future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to observe trends and derive more comprehensive conclusions.

Finally, this study investigated the effect of informational value and consumer engagement on purchase intention, with moderating factors limited to source credibility and generational cohorts. Future research could investigate other moderating factors, like message content, individual differences (e.g., novelty seeking), or the impact of different virtual influencer traits, to deepen our understanding of how virtual influencers’ sponsored posts shape consumer behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C., N.M.I., S.P. and C.C.; methodology, N.C. and N.M.I.; investigation, N.C. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C., N.M.I., S.P. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, N.C., N.M.I., S.P. and C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Business Management, College of Business, Universiti Utara Malaysia on 18 January 2024. All participants provided informed consent, and the confidentiality of the data was strictly maintained.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement Items

| Variable | Items | Source |

| Informativeness | 1 Sponsored posts shared by virtual influencers provide me with timely product information. | [33] |

| 2 Sponsored posts shared by virtual influencers provide me with relevant product information. | ||

| 3 Sponsored posts shared by virtual influencers are a good source of information about a brand or product. | ||

| Entertainment | Sponsored posts shared by virtual influencers are | |

| 1 …… entertaining. | ||

| 2 …… enjoyable. | ||

| 3 …… pleasing. | ||

| Incentives | 1 To receive rewards (e.g., free hours, coupons, etc.), I respond to sponsored posts shared by virtual influencers. | [72] |

| 2 I receive rewards (e.g., free hours, coupons, etc.) for sponsored posts shared by virtual influencers. | ||

| 3 I am satisfied with sponsored posts that include rewards (e.g., free hours, coupons, etc.). | ||

| 4 I take action to get sponsored posts that include rewards (e.g., free hours, coupons, etc.). | ||

| Novelty | The posts shared by virtual influencers are: | [71] |

| 1 …… novel | ||

| 2 …… unique | ||

| 3 …… unusual | ||

| 4 …… striking | ||

| Consumer engagement | 1 I will check out sponsored posts (including words, pictures, videos, etc.) posted by virtual influencers on social media. | [95] |

| 2. I would like sponsored posts (including words, pictures, videos, etc.) on social media by virtual influencers. | ||

| 3 I will comment on sponsored posts (including words, pictures, videos, etc.) posted by virtual influencers on social media. | ||

| 4 I will share sponsored posts (including words, pictures, videos, etc.) posted by virtual influencers on social media. | ||

| 5 I will create information related to the sponsored posts shared by the virtual influencers on social media. | ||

| Source credibility | I think the virtual influencers are | [73] |

| 1 …… attractive | ||

| 2 …… classy | ||

| 3 …… beautiful | ||

| 4 …… elegant | ||

| 5 …… sexy | ||

| For the products they mentioned in sponsored posts, virtual influencers are | ||

| 1 …… expert | ||

| 2 …… experienced | ||

| 3 …… knowledgeable | ||

| 4 …… qualified | ||

| 5 …… skilled | ||

| I think the virtual influencers are | ||

| 1 …… trustworthy | ||

| 2 …… dependable | ||

| 3 …… honest | ||

| 4 …… reliable | ||

| Purchase intention | 1 I think I will probably buy the products recommended by virtual influencers on social media. | [70] |

| 2 I think I will buy the products recommended by virtual influencers on social media. | ||

| 3 I would like to buy the products recommended by virtual influencers on social media. |

References

- Xie-Carson, L.; Benckendorff, P.; Hughes, K. Not so different after all? A netnographic exploration of user engagement with non-human influencers on social media. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 167, 114149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research, S. Virtual Influencer Market Size is Projected to Reach USD 111.78 Billion by 2033, Growing at a CAGR of 38.4%: Straits Research. 2025. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/02/20/3029529/0/en/Virtual-Influencer-Market-Size-is-Projected-to-Reach-USD-111-78-Billion-by-2033-Growing-at-a-CAGR-of-38-4-Straits-Research.html (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Kim, I.; Ki, C.-W.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.-K. Virtual influencer marketing: Evaluating the influence of virtual influencers’ form realism and behavioral realism on consumer ambivalence and marketing performance. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 176, 114611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Kiew, S.T.J.; Chen, T.; Lee, T.Y.M.; Ong, J.E.C.; Phua, Z. Authentically fake? How consumers respond to the influence of virtual influencers. J. Advert. 2023, 52, 540–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.J.; Ahn, S.J. A systematic review of virtual influencers: Similarities and differences between human and virtual influencers in interactive advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2023, 23, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, W. A trend or is the future of influencer marketing virtual? The effect of virtual influencers and sponsorship disclosure on purchase intention, brand trust, and consumer engagement. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Lei, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Yuan, H. Can you sense without being human? Comparing virtual and human influencers endorsement effectiveness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Dickinger, A.; So, K.K.F.; Egger, R. Artificial intelligence-generated virtual influencer: Examining the effects of emotional display on user engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.R.; Lee, H.-S. A Study on the Regulatory Fit Effects of Influencer Types and Message Types. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 5161–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y. Virtual Influencers in Advertisements: Examining the Role of Authenticity and Identification. J. Interact. Advert. 2024, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Tan, S.-S.; Chen, X. Investigating consumer engagement with influencer-vs. brand-promoted ads: The roles of source and disclosure. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Babu, M.M.; Hossain, M.A.; Hani, U. Value co-creation on a shared healthcare platform: Impact on service innovation, perceived value and patient welfare. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikovskaja, V.; Hubert, M.; Grunert, K.G.; Zhao, H. Driving marketing outcomes through social media-based customer engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrei, G.; Filieri, R.; Kennedy, L. Social media interactions, purchase intention, and behavioural engagement: The mediating role of source and content factors. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Rasul, T. Customer engagement and social media: Revisiting the past to inform the future. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducoffe, R.H. Advertising value and advertising on the web. J. Advert. Res. 1996, 36, 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Xie-Carson, L.; Magor, T.; Benckendorff, P.; Hughes, K. All hype or the real deal? Investigating user engagement with virtual influencers in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 99, 104779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagür, Z.; Becker, J.-M.; Klein, K.; Edeling, A. How, why, and when disclosure type matters for influencer marketing. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2022, 39, 313–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Castillo, D.; Sánchez-Fernández, R. The role of digital influencers in brand recommendation: Examining their impact on engagement, expected value and purchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhu, J. From source credibility to risk perception: How and when climate information matters to action. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Jain, V.; Rana, P. The moderating role of consumer personality and source credibility in celebrity endorsements. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 5, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnychuk, H.-A.; Arasli, H.; Nevzat, R. How to engage and attract virtual influencers’ followers: A new non-human approach in the age of influencer marketing. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2024, 42, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Ran, Y.; Wu, B.; Wang, V.L.; Zhou, L.; Wang, C.L. Virtual versus human: Unraveling consumer reactions to service failures through influencer types. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 178, 114657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolot, A. The characteristics of Generation Z. E-mentor 2018, 74, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.J.; Garris, R.O., III. Managing personal finance literacy in the United States: A case study. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boissieu, E.; Baudier, P. The perceived credibility of human-like social robots: Virtual influencers in a luxury and multicultural context. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2023, 36, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ou, W.; Lee, C.S. Investigating consumers’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement in social media brand pages: A natural language processing approach. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 54, 101179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Li, Z.; Na, S. How customer engagement in the live-streaming affects purchase intention and customer acquisition, E-tailer’s perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, N.; Isa, N.M.; Perumal, S. Effects of prior negative experience and personality traits on WeChat and TikTok ad avoidance among Chinese Gen Y and Gen Z. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardja, U.; Hongsuchon, T.; Hariguna, T.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Understanding impact sustainable intention of s-commerce activities: The role of customer experiences, perceived value, and mediation of relationship quality. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergel, M.; Frank, P.; Brock, C. The role of customer engagement facets on the formation of attitude, loyalty and price perception. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 890–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackett, L.K.; Carr, B.N. Cyberspace advertising vs. other media: Consumer vs. mature student attitudes. J. Advert. Res. 2001, 41, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Han, J. Why smartphone advertising attracts customers: A model of Web advertising, flow, and personalization. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 33, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, E.; Kirkbir, F. Customer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale in hospitals. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2007, 5, 252–268. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q. Consumer engagement in live streaming commerce: Value co-creation and incentive mechanisms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsenyan, J.; Mirowska, A. Almost human? A comparative case study on the social media presence of virtual influencers. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2021, 155, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touni, R.; Kim, W.G.; Haldorai, K.; Rady, A. Customer engagement and hotel booking intention: The mediating and moderating roles of customer-perceived value and brand reputation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 104, 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, R. The sources of novelty: A cultural and systemic view of distributed creativity. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2006, 15, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, E.; Lamba, N.; Mahmoud, D.; Ranganathan, C. Blurring lines between fiction and reality: Perspectives of experts on marketing effectiveness of virtual influencers. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Cyber Security and Protection of Digital Services (Cyber Security), Dublin, Ireland, 15–19 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Talukdar, N.; Yu, S. Breaking the psychological distance: The effect of immersive virtual reality on perceived novelty and user satisfaction. J. Strateg. Mark. 2024, 32, 1147–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Sundar, S.S. Interactivity and memory: Information processing of interactive versus non-interactive content. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, E.; Yang, J. How perceived interactivity affects consumers’ shopping intentions in live stream commerce: Roles of immersion, user gratification and product involvement. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 17, 754–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Qiu, X. AI technology and online purchase intention: Structural equation model based on perceived value. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Huang, Q. Digital influencers, social power and consumer engagement in social commerce. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 178–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Belanche, D.; Fernández, A.; Flavián, M. Influencer marketing on TikTok: The effectiveness of humor and followers’ hedonic experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M. When digital celebrity talks to you: How human-like virtual influencers satisfy consumer’s experience through social presence on social media endorsements. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrando, C.; Hoyos, M.J.M. Influencer endorsement posts and their effects on advertising attitudes and purchase intentions. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 2288–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, C.A. Groeppel-Klein and K. Müller. Consumers’ responses to virtual influencers as advertising endorsers: Novel and effective or uncanny and deceiving? J. Advert. 2023, 52, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.-P.; Breves, P.L.; Anders, N. Parasocial interactions with real and virtual influencers: The role of perceived similarity and human-likeness. New Media Soc. 2022, 26, 14614448221102900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Ma, J.W. Factors influencing parasocial relationship in the virtual reality shopping environment: The moderating role of celebrity endorser dynamism. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.-W. Examining the effects of personalized app recommender systems on purchase intention: A self and social-interaction perspective. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2017, 18, 336–745. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, M.M.; Ho, S.-C.; Liang, T.-P. Consumer Attitudes Toward Mobile Advertising: An Empirical Study. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2014, 8, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Frethey-Bentham, C.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social media engagement behavior: A framework for engaging customers through social media content. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2213–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Deng, X.; Wu, B.; Chen, Y. Money matters? Effect of reward types on customers’ review behaviors. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2023, 18, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.; Swaminathan, V.; Brooks, G. Driving Brand Engagement Through Online Social Influencers: An Empirical Investigation of Sponsored Blogging Campaigns. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Wong, I.A.; Prentice, C.; Liu, M.T.; Research, T. Customer engagement and its outcomes: The cross-level effect of service environment and brand equity. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serman, Z.E.; Sims, J. Source credibility theory: SME hospitality sector blog posting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 2317–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovland, C.I.; Weiss, W. The influence of source credibility on communication effectiveness. Public Opin. Q. 1951, 15, 635–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Bakshi, A. Exploring the impact of beauty vloggers’ credible attributes, parasocial interaction, and trust on consumer purchase intention in influencer marketing. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio Rizzo, G.L.; Berger, J.A.; Ordenes, F.V. What Drives Virtual Influencer’s Impact? SSRN 2023, 4329150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghakhani, N.; Oh, O.; Gregg, D.; Jain, H. How review quality and source credibility interacts to affect review usefulness: An expansion of the elaboration likelihood model. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 1513–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Luo, X.; Schatzberg, L.; Sia, C.L. Impact of informational factors on online recommendation credibility: The moderating role of source credibility. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 56, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Fuentes-García, F.J.; Cano-Vicente, M.C.; González-Mohino, M. How Generation X and Millennials perceive influencers’ recommendations: Perceived trustworthiness, product involvement, and perceived risk. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 1431–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, N.B. The cohort as a concept in the study of social change. In Cohort Analysis in Social Research: Beyond the Identification Problem; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Childers, C.; Boatwright, B. Do digital natives recognize digital influence? Generational differences and understanding of social media influencers. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2021, 42, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, D.K. Determining behavioural differences of Y and Z generational cohorts in online shopping. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2022, 50, 880–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings; Pearson Prentice Hall: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ChoZan. China’s Growing Virtual KOL Economy: What Brands Need to Konw. Available online: https://chozan.co/blog/chinas-virtual-kol-economy-what-brands-need-to-know/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Zhu, L.; Li, H.; Wang, F.-K.; He, W.; Tian, Z. How online reviews affect purchase intention: A new model based on the stimulus-organism-response (S-O-R) framework. Aslib. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 72, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, J.J.; Popa, M.; Smith, M.C. The sound of brands. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.H. Factors Influencing Consumer Acceptance of Mobile Advertising. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ohanian, R. Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. J. Advert. 1990, 19, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursachi, G.; Horodnic, I.A.; Zait, A. How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, S.; Akram, U.; Halibas, A. Artificial intelligence is the magic wand making customer-centric a reality! An investigation into the relationship between consumer purchase intention and consumer engagement through affective attachment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 77, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Guo, L.; Hu, M.; Liu, W. Influence of customer engagement with company social networks on stickiness: Mediating effect of customer value creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. Digital marketing strategies that Millennials find appealing, motivating, or just annoying. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.Y.; Kim, Y. Predicting online purchase intentions for clothing products. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 883–897. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Qie, K.; Memon, H.; Yesuf, H.M. The empirical analysis of green innovation for fashion brands, perceived value and green purchase intention—Mediating and moderating effects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, S.; Eisend, M.; Koslow, S.; Dahlen, M. A meta-analysis of when and how advertising creativity works. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littler, D.; Melanthiou, D. Consumer perceptions of risk and uncertainty and the implications for behaviour towards innovative retail services: The case of internet banking. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2006, 13, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S.A.; Vela, E.G.; Li, W.; Dakhan, S.A.; Thuy, T.T.H.; Merani, S.H.; Foroudi, P. Effects of perceived service quality, website quality, and reputation on purchase intention: The mediating and moderating roles of trust and perceived risk in online shopping. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1869363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Basu, S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kaur, S. Interactive voice assistants–Does brand credibility assuage privacy risks? J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Costa, C.; Oliveira, T.; Gonçalves, R.; Branco, F. How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 94, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth-Cohen, O.; Rosenb, H.; Lissitsa, S. Are you talking to me? Generation X, Y, Z responses to mobile advertising. Convergence 2022, 28, 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmesti, M.; Dharmesti, T.R.S.; Kuhne, S.; Thaichon, P. Understanding online shopping behaviours and purchase intentions amongst millennials. Young Consum. 2021, 22, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Generation Z: Technology and social interest. J. Individ. Psychol. 2015, 71, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Lin, J.S.; Shan, Y. Influencer marketing in China: The roles of parasocial identification, consumer engagement, and inferences of manipulative intent. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1436–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).