Abstract

With the rapid advancement of real-time interaction technologies and the continuous breakthroughs in marketing innovation, live streaming e-commerce has quickly become an essential marketing channel for brands. Its real-time and interactive nature significantly enhances consumer immersion in online shopping, thereby accelerating the decision-making process. This study investigates the impact of atmospheric cues in live streaming on impulse buying through the lens of flow experience. The findings reveal that expertise cues, interaction cues, and entertainment cues all contribute to enhancing consumers’ flow experience, which in turn, fosters impulse buying. Moreover, recognizing the importance of consumer heterogeneity, this study examines the moderating effect of self-construal. It finds that, once in a flow state, consumers with a stronger independent self-construal are more likely to engage in impulse buying than those with a more interdependent self-construal. The findings of this study provide valuable insights for brands on better leveraging live streaming e-commerce.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of mobile social media and e-commerce, the deep integration of live streaming and e-commerce has given rise to a new shopping model—live streaming e-commerce [1]. Combining real-time video streaming with online shopping has significantly enhanced consumers’ shopping experiences and rapidly evolved into a powerful tool for enterprise marketing and brand promotion [2,3]. According to CNNIC’s 54th report, the user base of live streaming e-commerce in China has reached 833 million, accounting for 79.2% of the total internet users (See: https://www.cnnic.net.cn/n4/2025/0117/c88-11229.html (accessed on 20 March 2025)). This vast user base not only demonstrates the extensive influence of live streaming e-commerce but also provides a solid foundation for its continued rapid development. The rise of live-streaming e-commerce reflects modern consumers’ demand for more convenient and efficient shopping experiences, as well as the transformation and innovation of traditional business models in the digital economy.

Live streaming e-commerce is not merely a new shopping method but also an experiential consumption model that meets both material and psychological needs [1]. Live streaming e-commerce, a product of marketing innovation, combines real-time interaction and intuitive product displays with emotional marketing. This allows consumers to feel a sense of participation and authenticity during their shopping experience [4]. In live streaming rooms, streamers use product demonstrations and expert explanations to create a professional atmosphere that satisfies the viewers’ need for easy access to product information [3,5,6]. Additionally, viewers can engage in real-time interactions with streamers and other viewers through bullet comments, participate in the content of the live streaming, and strengthen their emotional connection with the live streams [2,7]. Streamers also attract and maintain viewers’ attention through entertainment methods such as giving out lucky bags, holding raffles, and showcasing talents [8,9]. The atmospheric cues in live streaming provide consumers with a favorable shopping experience, making it easier for them to enter a state of flow. Live streaming e-commerce has evolved from a simple shopping channel into a new trend in experiential consumption.

Existing research on live streaming e-commerce has predominantly focused on areas such as streamer characteristics [6,10], technical features [11], streamer language style [9,12], and product attributes [1,13]. Although a few scholars have examined the atmosphere of live streaming e-commerce, they have mainly concentrated on physical cues like background decoration [14] and music tempo [15], with less attention given to the overall atmospheric cues created by the core features of live streaming. Live streaming e-commerce has been shown to significantly enhance consumers’ shopping experiences and increase conversion rates [16,17,18]. However, research on atmospheric cues—a critical driver in experiential marketing—remains insufficient in the context of live streaming e-commerce, and the mechanisms underlying their effects are not yet fully understood. Moreover, while consumer heterogeneity is a key factor in experience-oriented marketing, prior research has largely overlooked the role of consumer characteristics. To address this gap, this study poses three research questions:

- How do atmospheric cues in live streaming lead to consumers’ flow experiences?

- Does experiencing flow make consumers more likely to engage in impulse buying?

- How does consumer heterogeneity (self-construal) moderate the relationship between flow experience and impulse buying?

Guided by these research questions, this study adopts the SOR (Stimulus–Organism–Response) model to investigate how atmospheric cues in live streaming shape consumers’ flow experiences and, consequently, drive impulse buying. This study offers three major contributions. First, it expands the research perspective on the atmosphere of live streaming environments by shifting focus from physical factors to critical atmospheric cues—such as expertise, interaction, and entertainment—thereby providing a more holistic understanding of their psychological and behavioral effects. Second, it enriches the application of flow experience theory in live streaming e-commerce. Beyond identifying factors that trigger flow states and consumption behaviors, this study incorporates individual traits, thereby refining the theoretical framework. Finally, by introducing self-construal as a moderating variable, this study accounts for consumer heterogeneity, deepening the theoretical discourse on live streaming e-commerce.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Atmospheric Cues

Kotler introduced the concept of atmospherics, highlighting its deliberate design to elicit emotional responses from consumers, with the ultimate goal of enhancing purchase likelihood [19]. In the field of offline retail, extensive research has been conducted on the effects of atmospheric cues. Studies have confirmed the significant impact of store or mall atmospherics on consumers’ psychological states and actual behaviors [20,21]. Traditional atmospheric cues often include color schemes, lighting, music, scents, interior design, and product displays [22]. Similarly, in the realm of online shopping, the influence of atmospherics on consumer behavior and emotional attitudes has been widely explored by scholars [23,24]. Elements such as the placement of background music [25], animated images [26], and store layout design [27] have been shown to affect consumers emotional responses. In addition to the common atmospheric variables mentioned above, factors such as informativeness, social factors, and entertainment have also emerged as antecedent variables in the study of store atmospheres [28].

The rapid success of live streaming e-commerce has also drawn scholarly attention to its atmospheric cues. Existing research has already investigated the impact of background music [15] and visual complexity of the background [17] on consumers’ emotional and behavioral responses. Unlike other forms of sales, live commerce is characterized by a high level of real-time interactivity [1]. With the advancement of technology, live streamers can now deliver real-time product demonstrations, share expert insights, and provide practical usage solutions during live streams. This interactive format allows viewers to witness genuine, unfiltered reactions from the streamers, enhancing trust and engagement [5,29,30]. Viewers can also engage in real-time interactive communication with the streamers and other viewers through features like live comments, actively participating in the content of the live streaming [2,3,7]. Additionally, streamers often employ entertainment tactics, such as hosting giveaways, distributing coupons, or showcasing talents (e.g., singing, dancing, or telling jokes), to capture viewers’ attention [8,9]. Considering the unique nature of live commerce, this study examines the expertise cues, interaction cues, and entertainment cues in live streaming e-commerce.

2.2. Flow Experience

The theory of flow experience was first introduced by psychologist Csikszentmihalyi [31], who defined it as the holistic sensation of being fully immersed in an activity. Currently, academia lacks a universally accepted definition of flow experience. Ghani and Deshpande [32] identified two key characteristics of flow: the focus on a specific activity and the enjoyment derived from it. Novak et al. [33] were the first to apply the concept of flow to online shopping, suggesting that flow acts like “glue,” holding consumers’ attention. Additionally, some scholars have attempted to explain the concept of flow experience from multiple dimensions. Webster et al. [34] broke it down into focus, curiosity, intrinsic interest, and control. Koufaris [35] viewed flow as a combination of emotional and cognitive states and categorized it into three dimensions: enjoyment, focus, and perceived control. Pelet et al. [36] examined flow experience in the context of social media, dividing it into five dimensions—enjoyment, focus, challenge, control, and curiosity—verifying that all dimensions, except for control, are positively correlated with overall flow.

Since its inception, flow theory has found extensive application across diverse domains including sports [37], distance education [38], online gaming [39], work [40], and online shopping [33]. Live streaming e-commerce enables real-time interaction and provides an engaging shopping experience. This often leads consumers to lose track of time and their surroundings, immersing them in the live stream and inducing a state of flow [41]. Scholars have examined the antecedents that lead consumers to enter a state of flow in the context of live streaming e-commerce, as well as their subsequent behavioral intentions. Details can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Flow theory in live streaming e-commerce.

2.3. Self-Construal

Based on the influence of culture on the formation of individual self-concept, Markus and Kitayama [46] introduced the concept of self-construal, which refers to the extent to which individuals perceive themselves as separate from others. They categorized self-construal into two types: independent and interdependent. Since its introduction, this theory has significantly influenced psychology [47]. In the late 1990s, it was incorporated into consumer behavior research, particularly in areas such as information processing and categorization [48], brand evaluation [49], advertising attitudes [50], purchasing behavior [51], and decision-making [52]. Kacen and Lee [53] found that individuals with an independent self-construal are more likely to engage in impulse buying. Given the increasing competition in live streaming and the homogenization of marketing strategies, consumer personality traits have become a critical consideration for businesses. Therefore, this study introduces self-construal as a personality trait to explore how consumers with different self-construal tendencies respond to live streaming marketing stimuli.

2.4. Impulse Buying

Impulse buying has long been a hot topic in the field of marketing. Rook [54] defined impulse buying as a sudden and intense urge to purchase a product, which is a narrower and more specific concept compared to unplanned buying. This definition has gained wide recognition in the academic community. Early studies on impulse buying primarily focused on the products that trigger this behavior, often overlooking the impact of consumer characteristics and personal traits [55]. The development of e-commerce has expanded the research landscape for impulse buying. In the early stages of e-commerce, scholars explored the impact of website quality and product type on impulse buying [56]. Subsequently, researchers began to consider internal factors such as consumer personality traits and emotional responses, leading to a more comprehensive exploration of the determinants of impulse buying [57].

As live streaming e-commerce emerges as a new form of marketing, its diverse promotional strategies offer fresh perspectives for studying impulse buying. Scholars have investigated various antecedents that stimulate consumers’ impulse buying behavior or intentions in live streaming e-commerce, including scarcity promotions [16], marketing signals [5], streamers’ characteristics [58,59], streamers’ topic types [9], time pressure [44,60], product types [61], and social presence [62]. Although substantial research has been conducted on impulse buying, it remains a complex behavior. The antecedents that trigger impulse buying could be product-related factors, situational factors, emotional factors, or a combination of multiple factors. In conclusion, the mechanisms driving impulse buying in the emerging context of live streaming e-commerce still require further scholarly exploration.

3. Hypothesis Development

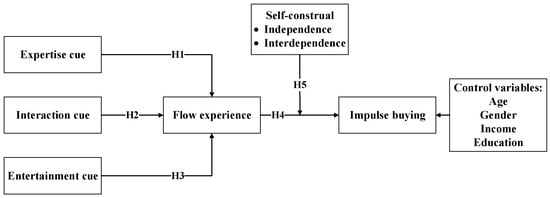

The study of the impact of atmosphere cues on consumer behavior is often conducted based on the SOR model [63]. This model posits that environmental stimuli influence individual’s emotional evaluations, which in turn determine their subsequent behavioral responses [64]. In this study, the primary research variables include atmosphere cues as environmental stimuli, flow experience as an organismic response, and impulse buying as a consumer behavioral response. Therefore, this research is based on the SOR model to explore the mechanism behind impulse buying behavior in live streaming environments (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.1. Atmospheric Cues and Flow Experience

3.1.1. Expertise Cue and Flow Experience

High-quality content and streamers’ expertise effectively address consumers’ diverse needs. This not only provides valuable information but also evokes positive emotional responses [6]. Professional product demonstrations and explanations reduce product uncertainty [3] and decrease consumers’ information search costs [5], facilitating the acquisition of product knowledge and leading to greater satisfaction and enjoyment [7]. This satisfaction and emotional engagement foster a deeper connection between consumers and the live streaming experience [1]. Additionally, the professional organization of content and well-planned live flow ensure a smooth and coherent viewing experience, keeping viewers fully engaged throughout the live streaming [65]. This reduces the likelihood of distractions caused by disorganized or incoherent content, allowing consumers to stay concentrated. As a result, they can gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of the live streaming content, contributing to an enhanced flow experience.

Hypothesis 1:

Expertise cues positively influence consumers’ flow experience.

3.1.2. Interaction Cue and Flow Experience

Interaction cues such as real-time comments, likes, and interactive Q&A sessions allow consumers to feel valued and acknowledged during their participation in the live streaming [2,29]. This interaction not only makes the viewing experience more enjoyable but also strengthens the emotional bond between consumers and the streamer, boosting overall enjoyment [65]. Moreover, when consumers actively engage in interaction, they are more likely to concentrate on the live streaming content, reducing external distractions and the potential for losing focus [41,66]. This concentration and engagement enable consumers to deeply immerse themselves in the live streaming atmosphere, making it easier to enter a state of flow.

Hypothesis 2:

Interaction cues positively influence consumers’ flow experience.

3.1.3. Entertainment Cue and Flow Experience

Entertainment cues like humorous language, interactive games, and vivid performances can greatly enhance the viewing experience, making consumers more engaged in a relaxed atmosphere [67]. These entertaining elements can stimulate consumers’ positive emotions, resulting in a prolonged sense of enjoyment, which in turn encourages them to stay longer in the live rooms [68]. Furthermore, these entertainment cues attract and hold consumers’ attention, helping them maintain a high level of focus [8]. In a light and enjoyable environment, consumers are more open-minded, which makes it easier for them to sustain attention and engagement. This focus not only enhances their understanding and memory of the content but also reduces external distractions, allowing them to immerse themselves more deeply in the current experience.

Hypothesis 3:

Entertainment cues positively influence consumers flow experience.

3.2. Flow Experience and Impulse Buying

The state of flow significantly facilitates impulse buying among consumers [69,70]. When in a state of flow, consumers are intensely focused on the present experience, which leads to a disregard for external distractions and rational thought, making them more prone to impulsive decisions [44]. Additionally, the experience of flow is often associated with a distortion of time perception, causing consumers to underestimate the time spent on shopping platforms, thereby increasing the likelihood of impulse buying [69]. Furthermore, the heightened sense of enjoyment and satisfaction that accompanies flow can amplify consumers’ desire to make purchases, as they seek to prolong these positive emotions through immediate transactions [71,72]. Thus, the state of flow promotes impulsive purchasing by diminishing rational judgment, intensifying emotional drivers, and distorting time perception. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4:

Flow experience positively influences consumers impulse buying.

3.3. The Moderating Role of Self-Construal

Independent self-construal individuals tend to be more individualistic, emphasizing self-expression and personal achievement [73]. When in a state of flow, they are more focused on their own emotions and desires, making them more prone to impulsive purchasing decisions that align with their personal interests and preferences. In contrast, interdependent self-construal individuals place greater importance on social norms and group expectations [73]. Even in a flow state, they are likely to consider others’ opinions and societal expectations, leading to more cautious decision-making and a suppression of impulsive behaviors.

Hypothesis 5:

Self-construal moderates the relationship between flow experience and impulse buying, with (a) independent self-construal strengthening it, whereas (b) interdependent self-construal weakening it.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Sampling

This study utilized survey data collected from China, the world’s largest market for live-streaming e-commerce, with the most active user base globally [74]. To validate and predict the research model, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed [75], as it is considered a more robust estimation method when the sample size is below 500 [76]. The data for this study were collected from 441 live streaming e-commerce users, of whom 59.2% were female (n = 261). The majority of participants were aged between 26 and 35 years (n = 263) and held a bachelor’s degree or higher (n = 427). Further details are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic information.

4.2. Questionnaire and Measures

Respondents completed an online self-reported questionnaire written in Chinese. The questionnaire items were initially derived from empirically validated scales and then underwent a rigorous translation and back-translation process conducted by an experienced marketing Ph.D. holder with a track record of publications in international journals. These meticulous steps were taken to ensure the linguistic accuracy of the research instruments. To verify the logical accuracy, a pretest was conducted. Given that live streaming is a novel shopping method, the survey began with a screening question to ensure that participants had previous experience with watching live streaming. Furthermore, participants were prompted to answer truthfully, and attention checks were employed to enhance the quality of responses. Respondents were then asked to evaluate the atmospheric cues, flow experience, impulse buying, and self-construal associated with live streaming shopping using a seven-point Likert scale anchored from (1) “strongly disagree” to (7) “strongly agree”.

All measurement items (as shown in Appendix A) were pretested and adjusted to fit the context of shopping on live streaming. Atmospheric cues were measured following the research of [77], encompassing three variables: expertise (3 items), interaction (3 items), and entertainment (2 items). Flow experience was measured based on the study of Ghani and Deshpande [32], using two dimensions, enjoyment and concentration, with a total of 7 items. The measurement of self-construal was adapted from the study by Pusaksrikit and Kang [78], including 3 items for independence and 3 items for interdependence. Impulse buying was assessed by adapting the work of Beatty and Elizabeth Ferrell [79], including 3 measurement items.

5. Results

5.1. Common Method Bias

Given that this study utilized a questionnaire survey method, multiple variables were reported by the same respondent in the same measurement context, which may introduce common method bias. To assess the potential presence of such bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted. The results revealed that the first factor accounted for 39.92% of the variance across all items, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. This indicates that there is no significant common method bias in this study.

5.2. Measurement Model

This study utilized Cronbach’s α to evaluate the reliability of the scale, as presented in Table 3. The α coefficients for all seven latent variables exceeded the threshold of 0.7, indicating strong reliability. The minimum factor loading was 0.623, which surpasses the acceptable threshold, thus permitting further analysis. Additionally, the composite reliability (CR) for all constructs was greater than 0.8, and the average variance extracted (AVE) was above 0.6, both of which are within acceptable limits, suggesting good convergent validity of the questionnaire. Furthermore, as shown in Table 4, the square roots of the average variance extracted are greater than the correlation coefficients among the variables, confirming the scale’s good discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Reliability and validity analyses.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficient matrix.

5.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5.3.1. Model Fit

Effect size f2 measures the contribution of predictor variables to the dependent variable. An f2 greater than 0.02 indicates that the predictor variable has an impact on the dependent variable, an f2 greater than 0.15 indicates a moderate impact, and an f2 greater than 0.35 indicates a large impact [80]. Table 5 provides preliminary evidence that expertise, interaction, and entertainment in atmospheric cues have an impact on the flow experience and that the flow experience influences impulse buying. The determination coefficients (R2) for flow experience and impulse buying are 0.681 and 0.332, respectively, both exceeding the minimum threshold of 25% [80], indicating that the model has good explanatory power.

Table 5.

Effect size and coefficient of determination.

5.3.2. Hypothesis Testing

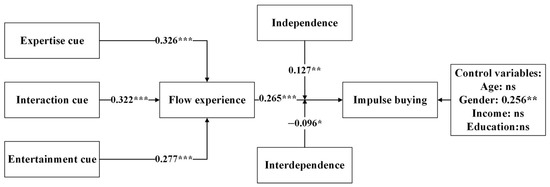

Using Smart PLS 4.0 for structural equation modeling of the research variables, the model paths are depicted in Figure 2, and the hypothesis testing results are summarized in Table 6. The results demonstrate that the expertise cue significantly enhances the flow experience (β = 0.326, p < 0.001), thus supporting Hypothesis 1. Similarly, the interaction cue exerts a notable positive influence on flow experience (β = 0.322, p < 0.001), corroborating Hypothesis 2. The entertainment cue also contributes significantly to flow experience (β = 0.277, p < 0.001), lending support to Hypothesis 3. Finally, the flow experience shows a significant positive effect on impulse buying (β = 0.265, p < 0.001), confirming Hypothesis 4.

Figure 2.

Results of the structural model. Note: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; ns means non-significant.

Table 6.

Hypothesis testing results.

Further verification of the mediating effect of flow experience was conducted using the bootstrapping method. The regression analysis results showed that the mediating effect of flow experience between interaction cue and impulse buying was significant (LLCI = 0.181, ULCI = 0.476, excluding 0), with a mediation effect value of 0.327; the mediating effect of flow experience between entertainment cue and impulse buying was significant (LLCI = 0.221, ULCI = 0.501, excluding 0), with a mediation effect value of 0.361; and the mediating effect of flow experience between expertise cue and impulse buying was significant (LLCI = 0.376, ULCI = 0.641, excluding 0), with a mediation effect value of 0.512.

The path coefficient results (see Table 6) indicate that the interaction between independence self-construal and flow experience has a significant positive effect on impulse buying (β = 0.127, p < 0.01), suggesting that the higher the consumer’s tendency toward independence, the stronger the positive impact of flow experience on impulse buying. Conversely, the interaction between interdependent self-construal and flow experience has a significant negative effect on impulse buying (β = −0.096, p < 0.05), indicating that the higher the consumer’s tendency toward interdependence, the weaker the positive impact of flow experience on impulse buying. Therefore, Hypotheses 5a and 5b are supported.

In addition, this study included factors such as age, gender, income, and educational background as control variables in the model to eliminate their potential influence. The results showed that age, income, and education did not have a significant impact on impulsive buying, while the gender variable had a significant effect (as shown in Figure 2). Specifically, females were more likely to make impulsive purchases compared to males. This finding is consistent with previous research, which suggests that males tend to be more rational in purchasing decisions.

6. Discussion

This study utilizes the SOR model framework to examine the determinants and mechanisms of impulse buying within the context of live streaming e-commerce. Specifically, it investigates the interrelations among atmospheric cues, flow experience, self-construal, and impulse buying behavior, leading to the following conclusions:

Firstly, atmospheric cues in the live streaming environment—namely expertise, interaction, and entertainment—positively influence consumers’ flow experience. The expertise cues cultivated during live streaming sessions meets consumers’ needs for information acquisition [6]. Professional product information provided by the streamer reduces the consumers’ information search costs [5,9], creating a sense of relaxation and positivity, thus facilitating the onset of a flow state. Additionally, the interaction cues and entertainment cues of the live streaming environment enhances the consumers’ sense of enjoyment and concentration, contributing to a deeper flow experience [2,29,67].

In addition, flow experience significantly influences impulse buying [69,70]. It not only positively affects impulse buying but also serves as a mediator between atmospheric cues (expertise cue, interaction cue, and entertainment cue) and impulse buying behavior. Impulse buying is frequently driven by consumers’ subjective emotions [54]. The flow experience, induced by the atmospheric cues in live streaming, creates a powerful and positive emotional state [32]. In this state, consumers become fully absorbed, losing awareness of their surroundings, which ultimately leads to impulse buying behavior [33].

Moreover, consumers’ self-construal moderates the relationship between flow experience and impulse buying behavior. An independent self-construal tendency amplifies the positive impact of flow experience on impulse buying. Consumers with a higher independent tendency focus more on personal feelings in their decision-making processes [73], making them more susceptible to impulse buying. In contrast, an interdependent self-construal tendency diminishes the effect of flow experience on impulse buying. Consumers with a higher interdependent tendency are more concerned with others’ opinions and exhibit more rational decision-making [73], thereby being less prone to impulse buying. The moderating effect of self-construal tendencies suggests a nuanced interplay between individual differences and the emotional experiences induced by live streaming environments.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Implications

This study expands the research perspective on the atmosphere of live streaming environments, enhancing the theoretical depth of the investigation. Unlike previous studies on the atmosphere of live streaming e-commerce, which typically consider physical factors like music tempo [15,25] and background settings [14], this study focuses on the core characteristics of live streaming. It explores how cues related to expertise, interaction, and entertainment within the live streaming environment impact the psychology and behavior of viewers, considering the overall atmosphere from an overall atmospheric perspective. Moreover, this study enriches the understanding of flow experience theory in the context of live streaming e-commerce. Beyond exploring factors that lead to consumers’ flow experiences and the subsequent consumption behaviors [41,42,43], this research also investigates the impact of individual traits, thereby deepening the understanding of flow experience theory. Additionally, this study considers the impact of consumer heterogeneity. Distinguishing from prior research on live streaming e-commerce, which mainly considers the influence of external stimuli on consumers [1,2,62], this study introduces self-construal as a moderating variable. It confirms that there are individual differences in the process from flow experience to impulse buying, thus reinforcing the boundary conditions for the application of the theoretical model.

7.2. Practical Implications

This study provides valuable marketing insights for live streaming e-commerce. First, streamers should employ various techniques to create an appropriate atmosphere during the live stream in order to attract and maintain viewers’ interest. For example, streamers can create a professional atmosphere through detailed product displays and expert explanations, enhance interactivity by responding to viewers’ questions in real time, and increase the entertainment factor with activities such as giveaways and talent shows. These strategies effectively improve viewers’ enjoyment and engagement, ensuring they remain highly focused on the content and thus enhancing their flow experience. Additionally, platforms can use AI technology to monitor atmospheric cues in real time, automatically detect changes in viewers’ emotional states, and alert streamers to adjust the content or interaction style to optimize the viewer experience. Through data analysis, platforms can assist streamers in identifying emotional fluctuations in viewers and adjust the live stream style and interactions accordingly, further increasing viewer participation and purchase intent. Moreover, platforms and streamers should fully consider consumer heterogeneity. Each consumer may have different psychological needs and levels of engagement during the live stream, which requires streamers and platforms to tailor strategies according to individual differences. For example, platforms can utilize big data and AI technology to analyze consumer behavior data, build detailed user profiles, and recommend the most suitable live stream atmosphere and content based on consumers’ self-construal or psychological characteristics.

7.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study explores the influencing factors and mechanisms of consumer impulse buying in the context of live streaming, offering both theoretical and practical significance, there are several limitations that need to be addressed in future research. Specifically, this study examines three types of atmospheric cues in live streaming. However, as both practical applications and theoretical understanding continue to evolve, these dimensions could be expanded in future research. For example, in addition to the current cues, factors such as novelty and humor could be incorporated to more comprehensively reflect the diverse impacts of the live streaming environment on consumer behavior.

In addition, this study focuses on the Chinese market, where the advanced development of live streaming e-commerce provides a rich data source. Nevertheless, the exclusive focus on this market may present certain cultural limitations. Due to differences in cultural backgrounds and social norms, the findings may not be directly generalizable to other regions. For instance, in Western countries, consumers’ impulse buying behavior may be influenced by distinct cultural factors, such as heightened privacy concerns, more rational decision-making, and stronger brand trust—elements that differ from those in China. Furthermore, regional social and cultural norms can shape purchasing decisions. While consumers in China may be more susceptible to group behaviors and social identification, those in Western countries may place a greater emphasis on individual independence. Therefore, future research could benefit from cross-cultural comparisons to explore differences in consumer attitudes and behaviors across various cultural contexts, as well as to further examine the impact of cultural factors on live streaming e-commerce and impulse buying behaviors.

Moreover, although this study collected 441 valid questionnaires through a professional survey company, yielding relatively rigorous research conclusions, there are still limitations when considering the dynamic and complex nature of live streaming. First, the cross-sectional self-reported data do not capture long-term changes in consumer behavior. To address this, future research could adopt longitudinal studies to track the evolution of consumer behavior over time. Second, the current approach did not fully address the dynamic nature of consumer behavior. In this regard, future studies could collect secondary data from live streaming sessions to monitor and analyze the dynamic changes in live streaming strategies. Finally, reliance on self-report data may introduce certain biases. To overcome this, future research could employ experimental designs and eye-tracking technology to provide more objective behavioral data, further validating the authenticity of flow and impulse buying behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.X. and W.L.; methodology, M.X.; software, L.J.; validation, Y.B., L.J. and W.L.; formal analysis, W.L.; investigation, L.J.; resources, Y.B.; data curation, M.X., W.L., L.J. and Y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.X. and W.L.; writing—review and editing, L.J. and Y.B.; visualization, W.L.; supervision, L.J. and Y.B.; project administration, L.J.; funding acquisition, L.J. and W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Laboratory Project of Higher Education Institutions in Shandong Province-Energy System Intelligent Management and Policy Simulation Laboratory at China University of Petroleum, grant number ZX20230214; Youth Innovation Team of Higher Education Institutions in Shandong Province-Data Intelligence Innovation Team at China University of Petroleum, grant number 2021RW041; National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 72302230; Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation Youth Project, grant number. ZR2023QG068.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the School of Economics and Management, China University of Petroleum (East China) (date of approval 28 May 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be shared on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Measurements

| Construct | Items | Reference |

| Expertise cue | I believe the streamer I watch demonstrates professionalism. | [77] |

| I believe the streamer I watch has extensive experience using the products they recommend. | ||

| I believe the streamer I watch possesses a wealth of expertise. | ||

| Interaction cue | I believe the streamer I watch and I have a good interactive relationship. | |

| I believe the streamer I watch creates content that effectively engages me. | ||

| I believe the content of the live streaming I watch captures my interest. | ||

| Entertainment cue | I believe the content of the live streaming is particularly humorous and entertaining. | |

| I believe the atmosphere created in the live streaming is especially relaxing. | ||

| Flow experience | When watching the live streaming, I feel very entertained. | [32] |

| When watching the live streaming, I feel very happy. | ||

| When watching the live streaming, I feel very enjoyable. | ||

| When watching the live streaming, I am fully focused on the stream. | ||

| When watching the live streaming, I am deeply engaged by the stream. | ||

| When watching the live streaming, I concentrate my attention on the stream. | ||

| When watching the live streaming, I am fully immersed in the stream. | ||

| Independent self-construal | Having a rich imagination is very important to me. | [78] |

| My personal identity, independent of others, is very important to me. | ||

| When dealing with people I’ve just met, I prefer to be frank and straightforward. | ||

| Interdependent self-construal | For the benefit of the group I belong to, I would sacrifice my own interests. | |

| If the team needs me, I will stay with the team even if I am unhappy. | ||

| I often feel that my relationships with others are more important than my own achievements. | ||

| Impulse buying | When watching live streaming, I am someone who buys products that weren’t originally planned. | [79] |

| When watching live streaming, I buy products that I hadn’t planned to purchase before. | ||

| Buying products from a live streaming uncontrollably is a very interesting thing. |

References

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Lu, J.; Guo, L.; Li, W. The dynamic effect of interactivity on customer engagement behavior through tie strength: Evidence from live streaming commerce platforms. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Chen, Z. Live streaming commerce and consumers’ purchase intention: An uncertainty reduction perspective. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, P.-S.; Dwivedi, Y.; Tan, G.; Ooi, K.-B.; Aw, E.; Metri, B. Why do consumers buy impulsively during live streaming? A deep learning-based dual-stage SEM-ANN analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Liu, W.; Jian, L. Live streaming product display or social interaction: How do they influence consumer intention and behavior? A heuristic-systematic perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 67, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Jian, L.; Sun, Z. 2023. How broadcasters’ characteristics affect viewers’ loyalty: The role of parasocial relationships. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, 36, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liang, X.; Tao, X.; Wang, H. See now, act now: How to interact with customers to enhance social commerce engagement? Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Qian, C.; Li, X.; Yuan, Q. How real-time interaction and sentiment influence online sales? Understanding the role of live streaming danmaku. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Xu, M.; Zheng, Y. Informative or affective? Exploring the effects of streamers’ topic types on user engagement in live streaming commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, C. Way to success: Understanding top streamer’s popularity and influence from the perspective of source characteristics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shao, X.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Nie, K. How live streaming influences purchase intentions in social commerce: An IT affordance perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 37, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Chen, K.; Qi, J.; Li, J.; Yu, I.Y. Creating immersive and parasocial live shopping experience for viewers: The role of streamers’ interactional communication style. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 17, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Duan, S.; Zhao, Y.; Lü, K.; Chen, S. The impact of online celebrity in livestreaming E-commerce on purchase intention from the perspective of emotional contagion. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yang, S. How background visual complexity influences purchase intention in live streaming: The mediating role of emotion and the moderating role of gender. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 103031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, D.; Li, X. The rhythm of shopping: How background music placement in live streaming commerce affects consumer purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Khan, J.; Su, Y.; Tong, J.; Zhao, S. Impulse buying tendency in live-stream commerce: The role of viewing frequency and anticipated emotions influencing scarcity-induced purchase decision. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yang, S.; Jiang, H. Do atmospheric cues matter in live streaming e-commerce? An eye-tracking investigation. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 62, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Chen, J.; Liao, J.; Hu, H.-L. What motivates users’ viewing and purchasing behavior motivations in live streaming: A stream-streamer-viewer perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Atmospherics as a Marketing Tool. J. Retail. 1973, 49, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, R.J.; Rossiter, J.R.; Marcoolyn, G.; Nesdale, A. Store atmosphere and purchasing behavior. J. Retail. 1994, 70, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, K.; Hesse, F.; Loesch, K. Store atmosphere, mood and purchasing behavior. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1997, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmashhara, M.G.; Soares, A.M. Linking atmospherics to shopping outcomes: The role of the desire to stay. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboubaker Ettis, S. Examining the relationships between online store atmospheric color, flow experience and consumer behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayburn, S.W.; Anderson, S.T.; Zank, G.M.; McDonald, I. M-atmospherics: From the physical to the digital. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, A.H.-C.; Oh, J. Interacting with background music engages E-Customers more: The impact of interactive music on consumer perception and behavioral intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Li, R.; Richard, M.-O.; Zhou, M. An investigation into online atmospherics: The effect of animated images on emotions, cognition, and purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A. An examination of the influences of store layout in online retailing. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1391–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Krasonikolakis, I.; Vrontis, D. A systematic literature review of store atmosphere in alternative retail commerce channels. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 153, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Dou, Y.; Xiao, Y. Understanding the role of live streamers in live-streaming e-commerce. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 59, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, H.; Tian, X. The dual-process model of product information and habit in influencing consumers’ purchase intention: The role of live streaming features. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 53, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ghani, J.; Deshpande, S. Task Characteristics and the Experience of Optimal Flow in Human-Computer Interaction. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 1994, 128, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, T.P.; Hoffman, D.L.; Yung, Y.-F. Measuring the Customer Experience in Online Environments: A Structural Modeling Approach. Mark. Sci. 2000, 19, 1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Trevino, L.K.; Ryan, L. The dimensionality and correlates of flow in human-computer interactions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 1993, 9, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the Technology Acceptance Model and Flow Theory to Online Consumer Behavior. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelet, J.-É.; Ettis, S.; Cowart, K. Optimal experience of flow enhanced by telepresence: Evidence from social media use. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ko, Y.J. The impact of virtual reality (VR) technology on sport spectators’ flow experience and satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Millat, I.; Martínez-López, F.J.; Huertas-García, R.; Meseguer, A.; Rodríguez-Ardura, I. Modelling students’ flow experiences in an online learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2014, 71, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, H.-M. What online game spectators want from their twitch streamers: Flow and well-being perspectives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Han, P.; Long, T. Teams’ stressors and flow experience: An energy-based perspective and the role of team mindfulness. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 183, 114860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Frank, B. Optimizing live streaming features to enhance customer immersion and engagement: A comparative study of live streaming genres in China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 103974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Q. The effects of tourism e-commerce live streaming features on consumer purchase intention: The mediating roles of flow experience and trust. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 995129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Peng, Y. What Drives Gift-giving Intention in Live Streaming? The Perspectives of Emotional Attachment and Flow Experience. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gu, M. Investigating the Key Drivers of Impulsive Buying Behavior in Live Streaming. J. Glob. Inf. Management 2022, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Hou, F.; Li, B.; Phang, C.W.; Chong, A.Y.-L. What influences the purchase of virtual gifts in live streaming in China? A cultural context-sensitive model. Inf. Syst. J. 2022, 32, 653–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Gilmour, R. Developing a new measure of independent and interdependent views of the self. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R. Green consumption by design: Interaction experiences and customization intentions. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 1375–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.; Puzakova, M.; Rocereto, J.F. When brand anthropomorphism alters perceptions of justice: The moderating role of self-construal. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2017, 34, 851–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Choi, S.M. Increasing Power and Preventing Pain: The Moderating Role of Self-Construal in Advertising Message Framing. J. Advert. 2011, 40, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Roy, R. How self-construal guides preference for partitioned versus combined pricing. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. What makes consumers take risks in self-other purchase decision making? The roles of impression management and self-construal. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2022, 50, e11170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacen, J.J.; Lee, J.A. The Influence of Culture on Consumer Impulsive Buying Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, D.W. The buying impulse. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakat, R.S.; Muruganantham, G. A Review of Impulse Buying Behavior. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2013, 5, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Kim, E.Y.; Funches, V.M.; Foxx, W. Apparel product attributes, web browsing, and e-impulse buying on shopping websites. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, T.; van Dolen, W. The influence of online store beliefs on consumer online impulse buying: A model and empirical application. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, X.; Zhu, P. How do e-commerce anchors’ characteristics influence consumers’ impulse buying? An emotional contagion perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Dastane, O.; Cham, T.-H.; Cheah, J.-H. Is ‘she’ more impulsive (to pleasure) than ‘him’ during livestream e-commerce shopping? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Zhan, S.; Zhu, Y. Can time pressure promote consumers’ impulse buying in live streaming E-commerce? Moderating effect of product type and consumer regulatory focus. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wang, M.; Qiao, T.; Shang, J. The Effects of Live Streamer’s Facial Attractiveness and Product Type on Consumer Purchase Intention: An Exploratory Study with Eye Tracking Technology. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, X.; Huang, X. “Oh, My God, Buy It!” Investigating Impulse Buying Behavior in Live Streaming Commerce. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 2436–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-J.; Eckman, M.; Yan, R.-N. Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2011, 21, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; Available online: http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1974-22049-000 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Cai, J. How attachment affects user stickiness on live streaming platforms: A socio-technical approach perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L. How to retain customers: Understanding the role of trust in live streaming commerce with a socio-technical perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shi, D.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, B. How Celebrity Endorsement Affects Travel Intention: Evidence From Tourism Live Streaming. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2024, 48, 1493–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, J.; Zhou, T. Research on Determinants Affecting Users’ Impulsive Purchase Intention in Live Streaming from the Perspective of Perceived Live Streamers’ Ability. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.-L.; Chen, K.-W.; Chiu, M.-L. Defining key drivers of online impulse purchasing: A perspective of both impulse shoppers and system users. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-T. Flow and social capital theory in online impulse buying. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Yang, J. Why online consumers have the urge to buy impulsively: Roles of serendipity, trust and flow experience. Manag. Decis. 2022, 60, 3350–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-L.; Chang, K.-C.; Kuo, N.-T.; Cheng, Y.-S. The mediating effect of flow experience on social shopping behavior. Inf. Dev. 2017, 33, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Maheswaran, D. The effects of self-construal and commitment on persuasion. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 31, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iResearch. 2023 China Live E-commerce Industry Research Report; iResearch: Shanghai, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two Structural Equation Models: LISREL and PLS Applied to Consumer Exit-Voice Theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, F.J., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Liu, F.; Duan, K.; Zhao, Y. Influence of Network Celebrity Live Broadcast on Consumers’ Virtual Gift Consumption from the Perspective of Information Source Characteristics. Manag. Rev. 2021, 33, 319–330. [Google Scholar]

- Pusaksrikit, T.; Kang, J. The impact of self-construal and ethnicity on self-gifting behaviors. J. Consum. Psychol. 2016, 26, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, S.E.; Elizabeth Ferrell, M. Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. J. Retail. 1998, 74, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications, Inc: Sauzende Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).