Why Uptake of Blended Internet-Based Interventions for Depression Is Challenging: A Qualitative Study on Therapists’ Perspectives

Abstract

1. Background

- What are the therapist perspectives on bCBT usability (e.g., perceived ease of use of the platform)?

- How satisfied are therapists with offering bCBT (e.g., overall satisfaction with bCBT)?

- What are the therapist perspectives on factors that promote or hinder the use of bCBT in daily practice (e.g., training, patient eligibility, safety)?

2. Methods

2.1. Therapists

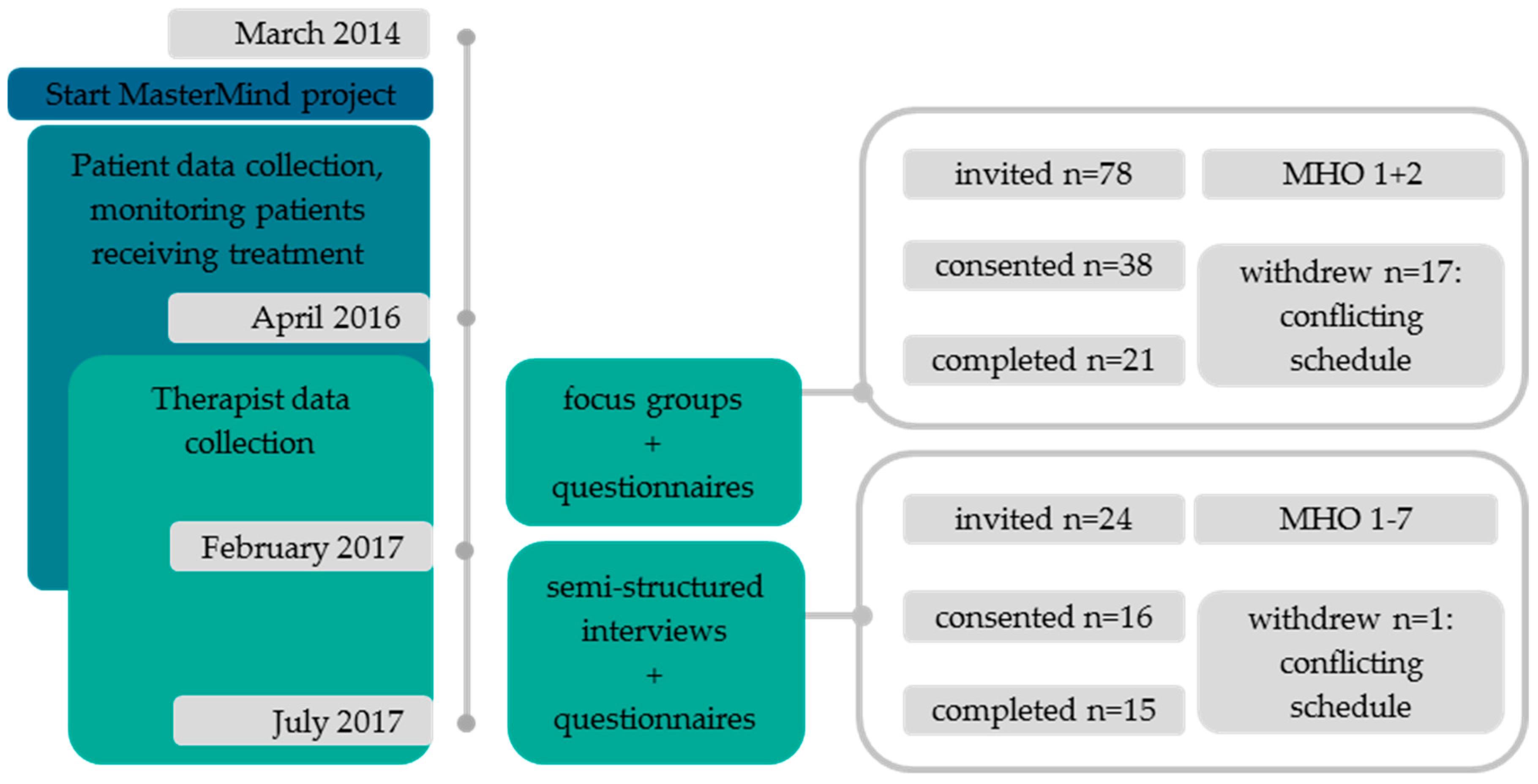

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Intervention

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Questionnaires

2.4.2. Focus Group Interviews

2.4.3. Semi-Structured In-Depth Interviews

2.5. Data Analyses

2.6. Ethical Issues

3. Results

3.1. bCBT Usability

3.2. bCBT Satisfaction

3.3. Factors That Promote or Hinder Uptake of bCBT

3.3.1. Theme (1) Therapists’ Needs Regarding bCBT Uptake

Therapist Training

Therapist Motivation

Therapist Readiness for Uptake

3.3.2. Theme (2) Therapists’ Role in Motivating Patients for bCBT

Informing Patients

Patient Eligibility

Patient Resistance

3.3.3. Theme (3) Therapists’ Experiences with bCBT

Effectiveness for Depression

Positive Effects

Negative Effects

Treatment Format

Therapeutic Relationship

Online Feedback Skills

Drop-Out and Safety

4. Discussion

4.1. Barriers to bCBT Uptake

4.2. Challenges with bCBT

4.3. Advantages of bCBT

4.4. Level of Experience

4.5. Limitations and Strengths

4.6. Future Uptake of bCBT

- Dissemination strategies: to change the focus of cost-effectiveness of bCBT towards personalization, adherence, and treatment quality improvement in disseminating information to therapists and patients. Within organizations, the uptake might gain from informing and motivating therapists and subsequently patients as well. There is a lot of room for improvement when it comes to sufficient knowledge about bCBT. Outside the organizations, patient demand can be stimulated by general practitioners and health insurance companies. Further, although evidence-based knowledge on bCBT is slowly becoming more available, this should be more widespread among patients, therapists, MHOs, and health insurance companies.

- Top down strategies: bCBT must be embedded top-down from start to finish overcoming its mere project status in many of the MHOs. This could be achieved by intensifying and extending training beyond technical aspects, and by facilitating the integration of ongoing support into existing consultation structures, (instead of creating special consultation options), in order to exchange knowledge and experience with bCBT. It would also help to remind therapists to offer bCBT to patients and to solve technical disconnections with administration- and other IT-systems within a well-equipped help desk. Whether imposing minimum usage norms (e.g., that 25% of the treatments must be blended in the Netherlands) could have a promoting effect is unclear, as this causes resistance for some, but motivated others.

- Bottom-up strategies: Fragmented use and individual uptake of the blended protocol can create a risk of it being costlier and of leading to a protocolled manner of working. Therapists’ need to personalize modules might be a result of uncertainty and their limited knowledge of all functionalities within the module and platform. Thus, besides a top-down approach, therapists might be more motivated and skilled if uptake is stimulated on a bottom-up basis, through discussing it on the work floor: For instance, it could help to start implementation with a small rollout with a motivated team of therapists, focusing on content development, enhancing online feedback skills and protocol use; to let the therapists be (co-) creators of modules; to construct a place and time within MHOs where therapists can think of ways to further develop bCBT; to experiment; to keep lines with the technical innovations on the platform within reach; including recurring evaluation in order to adapt strategies on the level of therapist experience and updates of the platform.

4.7. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cuijpers, P.; Noma, H.; Karyotaki, E.; Cipriani, A.; Furukawa, T.A. Effectiveness and Acceptability of Cognitive Behavior Therapy Delivery Formats in Adults with Depression: A Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Depression: The treatment and management of depression in adults. In Clinical Guideline 90; NICE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. In World Health Organization Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Boerema, A.M.; Kleiboer, A.; Beekman, A.T.F.; van Zoonen, K.; Dijkshoorn, H.; Cuijpers, P. Determinants of help-seeking behavior in depression: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, G.; Basu, A.; Cuijpers, P.; Craske, M.G.; McEvoy, P.; English, C.L.; Newby, J.M. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. J. Anxiety Disord. 2018, 55, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karyotaki, E.; Riper, H.; Twisk, J.; Hoogendoorn, A.; Kleiboer, A.; Mira, A.; MacKinnon, A.; Meyer, B.; Botella, C.; Littlewood, E.; et al. Efficacy of self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of depressive symptoms a meta-analysis of individual participant data. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titov, N.; Dear, B.; Nielssen, O.; Staples, L.; Hadjistavropoulos, H.; Nugent, M.; Adlam, K.; Nordgreen, T.; Bruvik, K.H.; Hovland, A.; et al. ICBT in routine care: A descriptive analysis of successful clinics in five countries. Internet Interv. 2018, 13, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, D.; Psych, D.; Eichert, H.C.; Riper, H.; Ebert, D.D. Blending face-to-face and internet-based interventions for the treatment of mental disorders in adults: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjistavropoulos, H.D.; Nugent, M.M.; Dirkse, D.; Pugh, N. Implementation of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy within community mental health clinics: A process evaluation using the consolidated framework for implementation research. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Definition Blended Treatment Heleen Riper. Triple-E Website. Available online: https://www.triple-ehealth.nl/en/projects-cat/depressie/ and http://www.webcitation.org/6wZFBY9pX (accessed on 18 January 2018).

- Kleiboer, A.; Smit, J.; Bosmans, J.; Ruwaard, J.; Andersson, G.; Topooco, N.; Berger, T.; Krieger, T.; Botella, C.; Baños, R.; et al. European COMPARative Effectiveness research on blended Depression treatment versus treatment-as-usual (E-COMPARED): Study protocol for a randomized controlled, non-inferiority trial in eight European countries. Trials 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romijn, G.; Batelaan, N.; Koning, J.; van Balkom, A.; de Leeuw, A.; Benning, F.; Hakkaart-van Roijen, L.; Riper, H. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of blended cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders in specialised mental health care: A 15-week randomised controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. 2019; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra, L.C.; Wiersma, J.E.; Ruwaard, J.J.; Neijenhuijs, K.; Lokkerbol, J.; Smit, F.; van Oppen, P.; Riper, H. Costs and effectiveness of blended versus standard cognitive behavioral therapy for depressed outpatients in routine specialized mental healthcare: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansson, K.N.; Skagius Ruiz, E.; Gervind, E.; Dahlin, M.; Andersson, G. Development and initial evaluation of an Internet-based support system for face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy: A proof of concept study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thase, M.E.; Wright, J.H.; Eells, T.D.; Barrett, M.S.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Balasubramani, G.K.; McCrone, P.; Brown, G.K. Improving the Efficiency of Psychotherapy for Depression: Computer-Assisted Versus Standard CBT. Am. J. Psychiatry 2017, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topooco, N.; Riper, H.; Araya, R.; Berking, M.; Brunn, M.; Chevreul, K.; Cieslak, R.; Ebert, D.D.; Etchmendy, E.; Herrero, R.; et al. Attitudes towards digital treatment for depression: A European stakeholder survey. Internet Interv. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vis, C.; Kleiboer, A.; Prior, R.; Bønes, E.; Cavallo, M.; Clark, S.A.; Dozeman, E.; Ebert, D.; Etzelmueller, A.; Favaretto, G.; et al. Implementing and up-scaling evidence-based eMental health in Europe: The study protocol for the MasterMind project. Internet Interv. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, M.; Dozeman, E.; van Schaik, D.J.F.; Vis, C.P.C.D.; Riper, H.; Smit, J.H. The therapist’s role in the implementation of internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with depression: Study protocol. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titzler, I.; Saruhanjan, K.; Berking, M.; Riper, H.; Ebert, D.D. Barriers and facilitators for the implementation of blended psychotherapy for depression: A qualitative pilot study of therapists’ perspective. Internet Interv. 2018, 12, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K. Triangulation 2.0 *. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2012, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooistra, L.C.; Ruwaard, J.; Wiersma, J.E.; van Oppen, P.; van der Vaart, R.; van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E.W.C.; Riper, H. Development and initial evaluation of blended cognitive behavioural treatment for major depression in routine specialized mental health care. Internet Interv. 2016, 4, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Official Journal of the European Union L 119/1. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Brooke, J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1996, 189, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, M.; van Schaik, A.; Dozeman, E.; Ruwaard, J.; Vis, C.; Ebert, D.D.; Etzelmueller, A.; Mathiasen, K.; Moles, B.; Mora, T.; et al. Dimensionality of System Usability Scale among professionals using internet-based interventions for depression: A confirmatory factor analysis. 2019; accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Sauro, J. A Practical Guide to the System Usability Scale: Background, Benchmarks & Best Practices; Measuring Usability LLC: Denver, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sauro, J.; Lewis, J.R. Quantifying user research. In Quantifying the User Experience; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attkisson, C.C.; Greenfield, T.K. The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) Scales. Outcome Assessment in Clinical Practice; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Boß, L.; Lehr, D.; Reis, D.; Vis, C.; Riper, H.; Berking, M.; Ebert, D.D. Reliability and validity of assessing user satisfaction with web-based health interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidholm, K.; Ekeland, A.G.; Jensen, L.K.; Rasmussen, J.; Pedersen, C.D.; Bowes, A.; Flottorp, S.A.; Bech, M. A model for assessment of telemedicine applications: Mast. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2012, 28, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, C.R.; Mair, F.; Finch, T.; MacFarlane, A.; Dowrick, C.; Treweek, S.; Rapley, T.; Ballini, L.; Ong, B.N.; Rogers, A.; et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivi, M.; Eriksson, M.C.M.; Hange, D.; Petersson, E.L.; Björkelund, C.; Johansson, B. Experiences and attitudes of primary care therapists in the implementation and use of internet-based treatment in Swedish primary care settings. Internet Interv. 2015, 2, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsen, M.; Hoifodt, R.S.; Kolstrup, N.; Waterloo, K.; Eisemann, M.; Chenhall, R.; Risor, M.B. Norwegian general practitioners’ perspectives on implementation of a guided web-based cognitive behavioral therapy for depression: A qualitative study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleiss, L.; Levin, B.; Paik, M.C. The measurement of interrater agreement. In Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Etzelmueller, A.; Radkovsky, A.; Hannig, W.; Berking, M.; Ebert, D.D. Patient’s experience with blended video- and internet based cognitive behavioural therapy service in routine care. Internet Interv. 2018, 12, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folker, A.P.; Mathiasen, K.; Lauridsen, S.M.; Stenderup, E.; Dozeman, E.; Folker, M.P. Implementing internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for common mental health disorders: A comparative case study of implementation challenges perceived by therapists and managers in five European internet services. Internet Interv. 2018, 11, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenter, R.M.F.; van de Ven, P.M.; Cuijpers, P.; Koole, G.; Niamat, S.; Gerrits, R.S.; Willems, M.; van Straten, A. Costs and effects of Internet cognitive behavioral treatment blended with face-to-face treatment: Results from a naturalistic study. Internet Interv. 2015, 2, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urech, A.; Krieger, T.; Möseneder, L.; Biaggi, A.; Vincent, A.; Poppe, C.; Meyer, B.; Riper, H.; Berger, T. A patient post hoc perspective on advantages and disadvantages of blended cognitive behaviour therapy for depression: A qualitative content analysis. Psychother. Res. 2018, 29, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, R.; Sigl, S.; Berger, T.; Laireiter, A.R. Patients’ Experiences of Web- and Mobile-Assisted Group Therapy for Depression and Implications of the Group Setting: Qualitative Follow-Up Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2018, 5, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feijt, M.A.; De Kort, Y.A.W.; Bongers, I.M.B.; IJsselsteijn, W.A. Perceived drivers and barriers to the adoption of eMental health by psychologists: The construction of the levels of adoption of eMental health model. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.J.; McMillen, J.C.; Proctor, E.K.; Carpenter, C.R.; Griffey, R.T.; Bunger, A.C.; Glass, J.E.; York, J.L. A compilation of strategies for implementing clinical innovations in health and mental health. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2012, 69, 123–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bührmann, L.; Schuurmans, J.; Ruwaard, J. Tailored Implementation of Internet-based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy in the Multinational Context of the ImpleMentAll Project: A Study Protocol for a Stepped Wedge Cluster Randomized Trial. under review.

| Therapist Demographics | n = 36 |

|---|---|

| Gender, female, n (%) | 29 (81) |

| Age in years, mean (SD; range) | 38 (9.5; 24–60) |

| Professional background, n (%) | |

| Licensed psychologists | 20 (56) |

| Psychologists in training under supervision for health care psychologists | 5 (14) |

| Mental health nurses | 5 (14) |

| Other (e.g., psychiatrists, prevention workers) | 6 (16) |

| Professional experience, n (%) | |

| 0–2 years | 3 (8) |

| 3–4 years | 8 (22) |

| 5–9 years | 10 (27) |

| 10 years or more | 15 (42) |

| bCBT depression treatment experience, n (%) | |

| 0 times | 6 (17) |

| 1–4 times | 15 (42) |

| 5–9 times | 8 (22) |

| 10–19 times | 2 (6) |

| 20 or more times | 5 (14) |

| Theme (1) Therapists’ Needs Regarding bCBT Uptake | Theme (2) Therapists’ Role in Motivating Patients for bCBT | Theme (3) Therapists’ Experiences with bCBT |

|---|---|---|

| Therapist training Therapist motivation Therapist readiness for uptake | Informing patients Patient eligibility Patient resistance | Effectiveness for depression Positive effects Negative effects Treatment protocol Therapeutic relationship Online feedback skills Drop-out and safety |

| Subtheme | Influencing Factors | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Therapist training | (+) sufficient to learn the technical aspects | “It is nice to have learned beforehand where all the buttons are and what the possibilities are.” (T11, no/little experience) |

| (−) lack of therapeutic content and guidelines in the training | “I miss therapeutic content in the training and the qualifications for the therapists to work with it.” (T25, experience) | |

| (−) training alone is not enough for uptake in daily practice | “There is one training and then you’re released with the notion: ‘now you can manage everything’.” (T7, experience) | |

| (−) lack of ongoing support | “There is a lack of time to delve into it, it should be facilitated better and not end with a single training.” (T14, no/little experience) | |

| Therapist motivation | (−) demotivated therapists | “What bothers me most when it comes to blended is that it has been made mandatory, mainly because we’ve to meet a certain percentage of blended treatments.” (T34, experience) |

| (+) motivated therapists | “If you are a psychologist, and you are interested in your profession, you should just use it.” (T9, experience) | |

| (−/+) undecided therapists | “You have to get out of your comfort zone to discover what the added value of blended is.” (T31, no/little experience) | |

| Therapist readiness for uptake | (−) small select group uses bCBT on a regular basis | “When I look at my team, it seems only one person is trained, I don’t really hear others talk about it.” (T36, experience) |

| (+) expected to grow in future | “I’d like to use blended in the future, but first I’d like more ideas on how to use it (T6, no/little experience) | |

| (−/+) making bCBT mandatory | “I once heard that you need a certain percentage of online contacts—that would work for me.” (T2, experience) |

| Subtheme | Influencing Factors | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Informing patients | (−) difficult to motivate some patients | “Sometimes there is so much going on, which leads me to inform patients in an insecure or doubtful way, that makes them say ‘no, I don’t want that’.” (T35, no/little experience) |

| (−) room for improvement | “I think that therapists should ‘sell’ or promote bCBT more with patients.” (T15, experience) | |

| Patient eligibility | (−) eligible patient unknown | “It is difficult to assess for whom it is eligible. Sometimes someone who grew up with computers says, ‘oh no, not for me’, and then a 65-year old says ‘nice, let’s do it’.” (T10, experience) |

| (−/+) discussion on comorbidity/complexity/depression severity | “I imagine that blended is less suitable for more complex cases. But if I consider what I have in my caseload now, I think it should be doable.” (T5, no/little experience) | |

| (+) eligibility bCBT = eligibility CBT | “In principle everyone is eligible for bCBT. I rarely think that it’s not an option.” (T7, experience) | |

| Patient resistance | (−) unclear image, too demanding, not enough, negative past experiences | “Patients don’t have a good image of bCBT. In their view it’s more like an online questionnaire than a complete module, ‘I’ve already answered those questions…’.” (T9, experience) |

| (+) patient demand expected to increase in the future | “I think it will make an essential difference if patients ask for it. That’s just a matter of time’.” (T1, no/little experience) |

| Subtheme | Influencing Factors | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness for depression | (+) effectiveness bCBT = effectiveness of CBT | “It is CBT in another format, it’s not suddenly a different treatment.” (T29, experience) |

| Positive effects | (+) containing therapist drift | “I don’t skip things. With bCBT, I think that I am much more thorough than without.” (T29, experience) |

| (+) making other diagnosis or problems more easily visible | “You notice much sooner if a patient has difficulties adhering to therapy, whether or not they are doing the work. This becomes clearer faster than in a FtF session.” (T1, no/little experience) | |

| (+) helps to remember information more easily | “In a FtF session you say a lot, but afterwards patients also forget quickly. Now they can review what they’ve learned as many times as they want.” (T10, experience) | |

| (+) reducing travel time | “In other countries, factors such as distances and climate play a role, but of course in the middle of the country we have traffic jams. bCBT is very nice for this.” (T9, experience) | |

| (+) more contact with patient | “Throughout the treatment you have more frequent short contact moments, which are actually very good.” (T10, experience) | |

| (+) sharing content with system | “For the patient you remove the treatment from therapist’s office to their own home.” (T12, no/little experience). | |

| (+) effect of writing | “Patients have to write, this is for many a very good instrument to order things and gain new insights. I find the writing a very positive addition to the verbal component.” (T15, experience) | |

| (+) monitoring homework | “I find it very attractive that there is more control over the homework that they have or haven’t done.” (T2, experience) | |

| (+) facilitating patient self-efficacy | “In the online part a degree of independence makes patients themselves engage with the treatment. I think that they attribute treatment success to themselves, more than with FtF treatment.” (T22, experience) | |

| Negative effects | (−) no gain in time, costs more | “I find it takes more time than I expected. Especially if you’re still unfamiliar with the module.” (T7, no/little experience) |

| (−) unsuitable content | “I had a traumatized patient, because she couldn’t have children. The first example on the platform was ‘I have children and I want to be a good mother...’.” (T27, no/little experience) | |

| Treatment format | (−/+) discussion on structure protocol | “I find it difficult to be flexible in the protocol and not to become a sort of CBT machine.” (T21, no/little experience) |

| (−/+) discussion on freedom in protocol to explore depression | “Usually, when I start without the platform, I think ‘never mind’. But also, when the patient isn’t ready for it initially, you can say ‘Later on, we will start with the online platform’.” (T31, no/little experience) | |

| (−/+) discussion on ‘what is blended’ | “I don’t think it’s 50/50. The main focus is more on the FtF sessions. I notice that the conversations and the modules do not always run parallel to each other.” (T14, no/little experience) | |

| (−/+) discussion on introduction platform | “Whether you start treatment with an online module, right at the outset or only when a basis has been formed, is dependent on the therapist. I think am very comfortable with starting right away.” (T1, no/little experience) | |

| Therapeutic relationship | (−/+) discussion on quality therapeutic relationship | “It’s possible to build a therapeutic relationship, but sometimes it isn’t. Yet I think that this isn’t dependent on bCBT. Also, with FtF therapy it’s possible to succeed in building a therapeutic relationship and sometimes not.” (T15, experience) |

| Online feedback skills | (−) time providing feedback (−) permanent character of online feedback | “I reflect more on what I want to write, that is perhaps the reason why it takes more time.” (T7, no/little experience) “It’s difficult to assess whether someone has understood something in the way you intended. If this happens in FtF contact you can talk around it, look friendly and explain. In black and white this is not possible.” (T5, no/little experience) |

| (+) connection online feedback and FtF conversations | “I notice that patients like to come back to a point during the conversations, to go through the exercises together.” (T12, no/little experience) | |

| Dropout & safety | (−/+) discussion on safety risks | “In the meantime, I experienced that it’s okay if the patient also comes to the FtF sessions. You’ve to make this clear at the start. The risk you lose contact is lower than I expected.” (T9, experience) |

| (+) bCBT has no extra risks with regards to suicidal ideation | “I thought that if you see someone less that it’d be more difficult to assess the suicide risk. But it can just as well lower the threshold to say something online more easily than to discuss FtF.” (T31, no/little experience) | |

| (+) drop-out bCBT = drop-out CBT | “I don’t have one type of patient that drops out of blended. It’s very unpredictable who completes it.” (T30, experience) | |

| (+) sufficient patient data safety | “I understood that the online platform is very safe, safer than email.” (T33, experience) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mol, M.; van Genugten, C.; Dozeman, E.; van Schaik, D.J.F.; Draisma, S.; Riper, H.; Smit, J.H. Why Uptake of Blended Internet-Based Interventions for Depression Is Challenging: A Qualitative Study on Therapists’ Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010091

Mol M, van Genugten C, Dozeman E, van Schaik DJF, Draisma S, Riper H, Smit JH. Why Uptake of Blended Internet-Based Interventions for Depression Is Challenging: A Qualitative Study on Therapists’ Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(1):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010091

Chicago/Turabian StyleMol, Mayke, Claire van Genugten, Els Dozeman, Digna J. F. van Schaik, Stasja Draisma, Heleen Riper, and Jan H. Smit. 2020. "Why Uptake of Blended Internet-Based Interventions for Depression Is Challenging: A Qualitative Study on Therapists’ Perspectives" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 1: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010091

APA StyleMol, M., van Genugten, C., Dozeman, E., van Schaik, D. J. F., Draisma, S., Riper, H., & Smit, J. H. (2020). Why Uptake of Blended Internet-Based Interventions for Depression Is Challenging: A Qualitative Study on Therapists’ Perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9010091