Efficacy of Autologous Conditioned Serum on the Dorsal Root Ganglion in Patients with Chronic Radicular Pain: Prospective Randomized Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Clinical Trial (RADISAC Trial)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

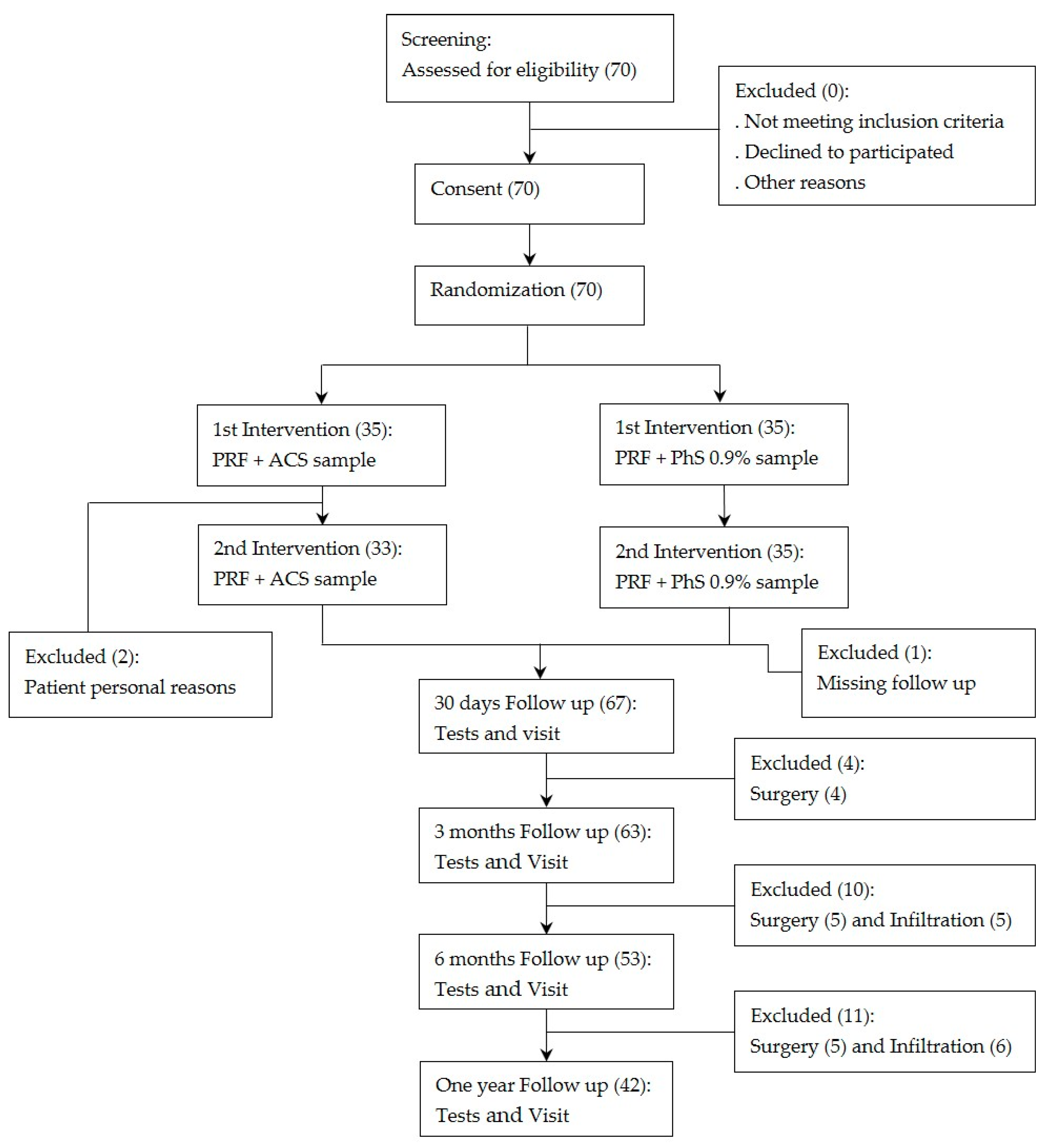

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Preparation of ACS

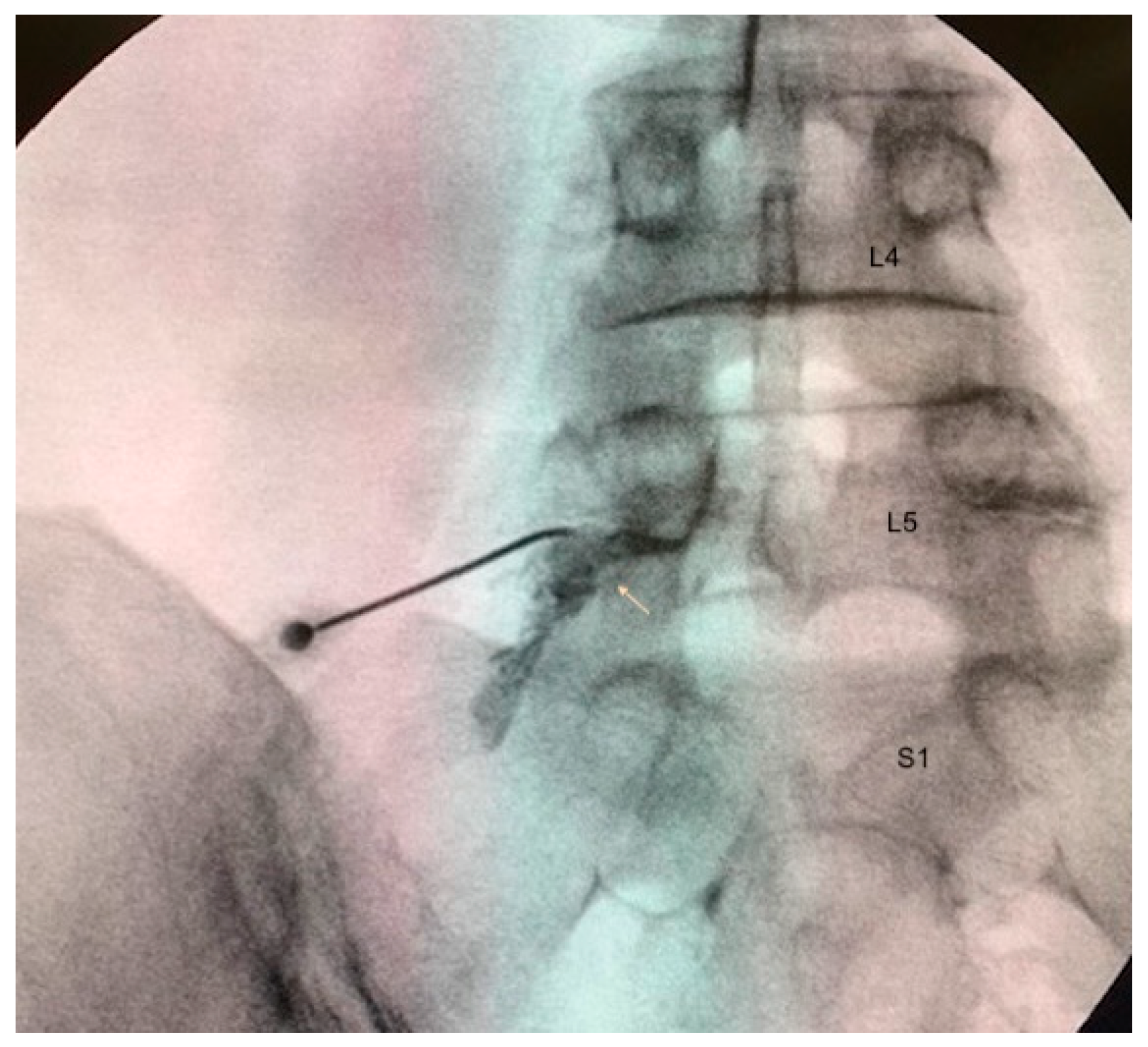

2.4. Treatment Administration

2.5. Clinical Outcomes

2.6. Safety Outcomes

2.7. Sample Size Calculation

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

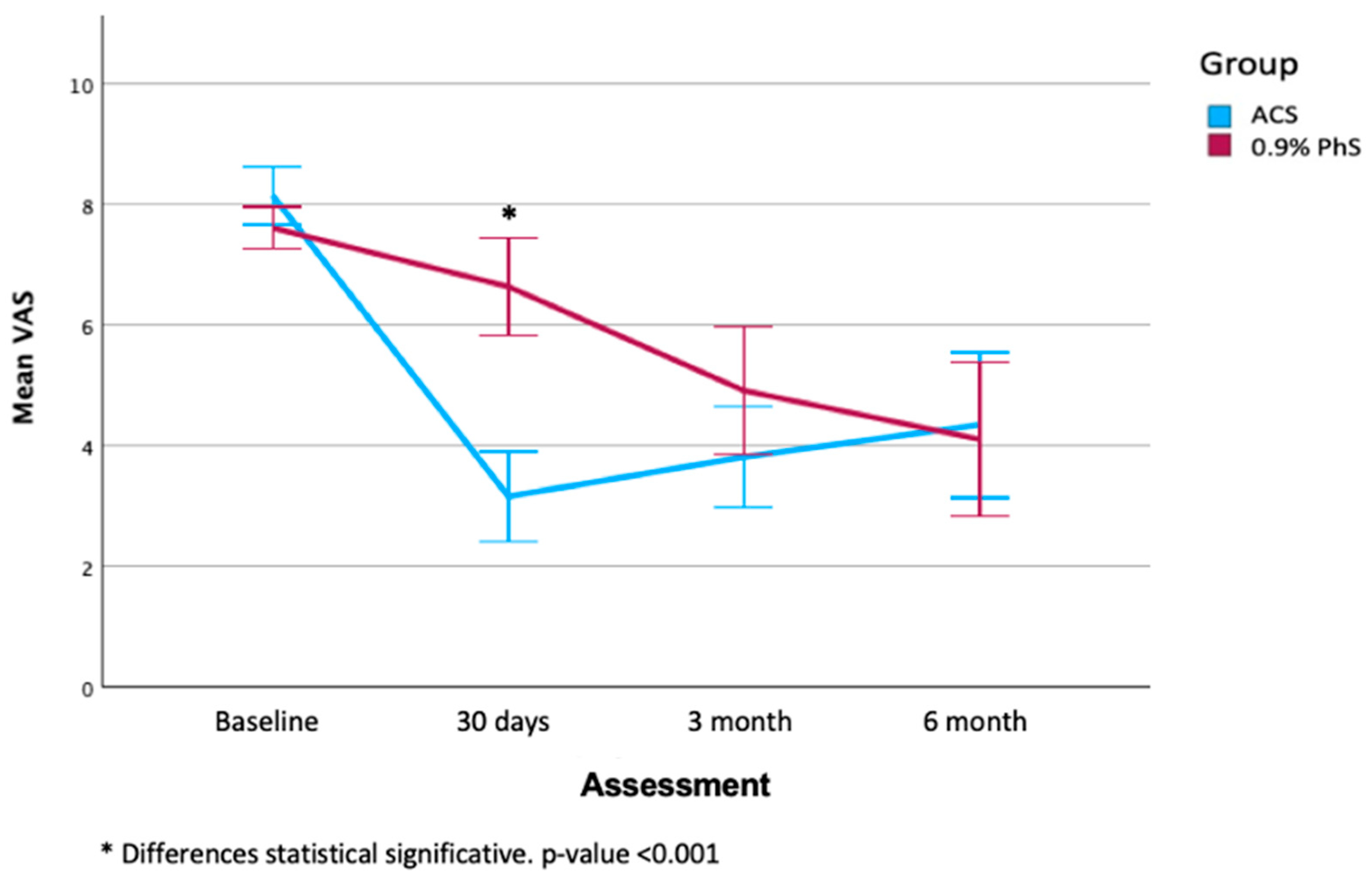

3.2. Clinical Evaluation

3.3. Safety Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRF | Pulsed Radiofrequency |

| DRG | Dorsal Root Ganglion |

| ACS | Autologous Conditioned Serum |

| LLRP | Lower Limb Radicular Pain |

| PhS | Physiological Saline |

| NPRS | Numeric Pain Rating Scale |

| ODS | Oswestry Disability Scale |

| MOAS | Mood Assessment Scale |

| DN4 | Douleur Neuropathique en 4 questions |

| SF-12 | Quality of Life assessment |

| CEIm | Committee Ethics Medical Investigation |

| DUH | Dexeus University Hospital |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| REML | Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| RLE | Right Lower Extremity |

| LLE | Left Lower Extremity |

| Cs | Corticosteroids |

| VAS | Visual Analogic Scale |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| IL | Interleukine |

| FGF-2 | Fibriblasts Growth Factor-2 |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor-β1 |

References

- Merskey, H.; Bogduk, N. Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms; IASP Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boxem, K.; Cheng, J.; Patijn, J.; van Kleef, M.; Lataster, A.; Mekhail, N.; Van Zundert, J. Lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2010, 10, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bou Peene, L.; Cohen, S.P.; Kallewaard, J.W.; Wolff, A.; Huygen, F.; Gaag, A.V.; Monique, S.; Vissers, K.; Gilligan, C.; Van Zundert, J.; et al. 1. Lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2024, 24, 525–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hincapié, C.A.; Kroismayr, D.; Hofstetter, L.; Kurmann, A.; Cancelliere, C.; Rampersaud, Y.R.; Boyle, E.; Tomlinson, G.A.; Jadad, A.R.; Hartvigsen, J.; et al. Incidence of and risk factors for lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy in adults: A systematic review. Eur. Spine J. 2025, 34, 263–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostelo, R.W.; de Vet, H.C. Clinically important outcomes in low back pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2005, 19, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerup, N.B.; Kuner, R.; Jensen, T.S. Neuropathic pain: From mechanisms to treatment. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 259–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, J.; Apeldoorn, A.; Hallegraeff, H.; Clark, J.; Smeets, R.; Malfliet, A.; Girbes, E.L.; De Kooning, M.; Ickmans, K. Low back pain: Guidelines for the clinical classification of predominant neuropathic, nociceptive, or central sensitization pain. Pain Physician 2015, 18, E333–E346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dower, A.; Davies, M.A.; Ghahreman, A. Pathologic Basis of Lumbar Radicular Pain. World Neurosurg. 2019, 128, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorami, A.K.; Oliveira, C.B.; Maher, C.G.; Bindels, P.J.E.; Machado, G.C.; Pinto, R.Z.; Koes, B.W.; Chiarotto, A. Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment of Lumbosacral Radicular Pain: A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luijsterburg, P.A.; Verhagen, A.P.; Ostelo, R.W.; van Os, T.A.; Peul, W.C.; Koes, B.W. Effectiveness of conservative treatments for the lumbosacral radicular syndrome: A systematic review. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 881–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchikanti, L.; Abdi, S.; Atluri, S.; Benyamin, R.M.; Boswell, M.V.; Buenaventura, R.M.; Bryce, D.A.; Burks, P.A.; Caraway, D.L.; Calodney, A.K.; et al. An update of comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for interventional techniques in chronic spinal pain. Part II: Guidance and recommendations. Pain Physician 2013, 16 (Suppl. S2), S49–S283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, R.Z.; Maher, C.G.; Ferreira, M.L.; Ferreira, P.H.; Hancock, M.; Oliveira, V.C.; McLachlan, A.J.; Koes, B. Drugs for relief of pain in patients with sciatica: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012, 344, e497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liem, L.; van Dongen, E.; Huygen, F.J.; Staats, P.; Kramer, J. The dorsal root ganglion as a therapeutic target for chronic pain. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2016, 41, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisset, X. Neuropathic pain: Evidence based recommendations. Presse Med. 2024, 53, 104232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finnerup, N.B.; Attal, N.; Haroutounian, S.; McNicol, E.; Baron, R.; Dworkin, R.H.; Gilron, I.; Haanpää, M.; Hansson, P.; Jensen, T.S.; et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moisset, X.; Bouhassira, D.; Avez Couturier, J.; Alchaar, H.; Conradi, S.; Delmotte, M.H.; Lanteri-Minet, M.; Lefaucheur, J.P.; Mick, G.; Piano, V.; et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for neuropathic pain: Systematic review and French recommendations. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 176, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abejón, D.; Garcia-del-Valle, S.; Fuentes, M.L.; Gómez-Arnau, J.I.; Reig, E.; van Zundert, J. Pulsed radiofrequency in lumbar radicular pain: Clinical effects in various etiological groups. Pain Pract. 2007, 7, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liem, L.; Russo, M.; Huygen, F.J.; Van Buyten, J.P.; Smet, I.; Verrills, P.; Cousins, M.; Brooker, C.; Levy, R.; Deer, T.; et al. A multicenter, prospective trial to assess the safety and performance of the spinal modulation dorsal root ganglion neurostimulator system in the treatment of chronic pain. Neuromodulation 2013, 16, 471–482; discussion 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munglani, R. The longer-term effect of pulsed radiofrequency for neuropathic pain. Pain 1999, 80, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, T.T.; Kraemer, J.; Nagda, J.V.; Aner, M.; Bajwa, Z. Response to pulsed and continuous radiofrequency lesioning of the dorsal root ganglion and segmental nerves in patients with chronic lumbar radicular pain. Pain Physician 2008, 11, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijter, M.E.; Cosman, E.R.; Rittman, W.B.; van Kleef, M. The effects of pulsed radiofrequency field applied to the dorsal root ganglion—A preliminary report. Pain Clin. 1998, 11, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Vancamp, T.; Levy, R.M.; Peña, I.; Pajuelo, A. Relevant Anatomy, Morphology, and Implantation Techniques of the Dorsal Root Ganglia at the Lumbar Levels. Neuromodulation 2017, 20, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagda, J.V.; Davis, C.W.; Bajwa, Z.H.; Simopoulos, T.T. Retrospective review of the efficacy and safety of repeated pulsed and continuous radiofrequency lesioning of the dorsal root ganglion/segmental nerve for lumbar radicular pain. Pain Physician 2011, 14, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schu, S.; Gulve, A.; ElDabe, S.; Baranidharan, G.; Wolf, K.; Demmel, W.; Rasche, D.; Sharma, M.; Klase, D.; Jahnichen, G.; et al. Spinal cord stimulation of the dorsal root ganglion for groin pain-a retrospective review. Pain Pract. 2015, 15, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, A.; Grandinson, M.; Sluijter, M. Pulsed radiofrequency for radicular pain due to a herniated intervertebral disc—An initial report. Pain Pract. 2005, 5, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, F.; Negro, A.; Russo, C.; Cirillo, S.; Caranci, F. Chronic intractable lumbosacral radicular pain, is there a remedy? Pulsed radiofrequency treatment and volumetric modifications of the lumbar dorsal root ganglia. Radiol. Med. 2021, 126, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Boxem, K.; Huntoon, M.; Van Zundert, J.; Patijn, J.; van Kleef, M.; Joosten, E.A. Pulsed radiofrequency: A review of the basic science as applied to the pathophysiology of radicular pain: A call for clinical translation. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2014, 39, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, J.H.; Jang, J.N.; Choi, S.I.; Song, Y.; Kim, Y.U.; Park, S. Pulsed radiofrequency of lumbar dorsal root ganglion for lumbar radicular pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Pract. 2024, 24, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakouri, S.K.; Dolati, S.; Santhakumar, J.; Thakor, A.S.; Yarani, R. Autologous conditioned serum for degenerative diseases and prospects. Growth Factors 2021, 39, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auw Yang, K.G.; Raijmakers, N.J.; van Arkel, E.R.; Caron, J.J.; Rijk, P.C.; Willems, W.J.; Zijl, J.A.; Verbout, A.J.; Dhert, W.J.; Saris, D.B. Autologous interleukin-1 receptor antagonist improves function and symptoms in osteoarthritis when compared to placebo in a prospective randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2008, 16, 498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltzer, A.W.; Moser, C.; Jansen, S.A.; Krauspe, R. Autologous conditioned serum (Orthokine) is an effective treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2009, 17, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzer, A.W.; Ostapczuk, M.S.; Stosch, D.; Seidel, F.; Granrath, M. A new treatment for hip osteoarthritis: Clinical evidence for the efficacy of autologous conditioned serum. Orthop. Rev. 2013, 5, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Baselga, J.; Hernandez, P.M. ORTHOKINE-Therapy for High-Pain Knee Osteoarthritis (OA) May Delay Surgery. Independent 2-Year Case Follow-Up; ICRS Congress: Izmir, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Darabos, N.; Haspl, M.; Moser, C.; Darabos, A.; Bartolek, D.; Groenemeyer, D. Intraarticular application of autologous conditioned serum (ACS) reduces bone tunnel widening after ACL reconstructive surgery in a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2011, 19 (Suppl. S1), S36–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchikanti, L.; Alturi, S.; Sanapati, M.; Hirsch, J.A. Epidural Administration of Biologics. In Essentials of Regenerative Medicine in Interventional Pain Management; Manchikanti, L., Navani, A., Sanapati, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 399–438. [Google Scholar]

- Wright-Carpenter, T.; Klein, P.; Schäferhoff, P.; Appell, H.J.; Mir, L.M.; Wehling, P. Treatment of muscle injuries by local administration of autologous conditioned serum: A pilot study on sportsmen with muscle strains. Int. J. Sports Med. 2004, 25, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.-W.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Altman, D.G.; Mann, H.; Berlin, J.; Dickersin, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Schulz, K.F.; Parulekar, W.R.; et al. SPIRIT 2013 Explanation and Elaboration: Guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013, 346, e7586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, N.J.; Monsour, A.; Mew, E.J.; Chan, A.W.; Moher, D.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Terwee, C.B.; Chee-A-Tow, A.; Baba, A.; Gavin, F.; et al. Guidelines for Reporting Outcomes in Trial Reports: The CONSORT-Outcomes 2022 Extension. JAMA 2022, 328, 2252–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homs, M.; Milà, R.; Valdés, R.; Blay, D.; Borràs, R.M.; Parés, D. Efficacy of conditioned autologous serum therapy (Orthokine®) on the dorsal root ganglion in patients with chronic radiculalgia: Study protocol for a prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blind clinical trial (RADISAC trial). Trials 2023, 24, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Childs, J.D.; Piva, S.R.; Fritz, J.M. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005, 30, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.; Pathak, H.; Churyukanov, M.V.; Uppin, R.B.; Slobodin, T.M. Low back pain: Critical assessment of various scales. Eur. Spine 2020, 29, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streiner, D.L.; Norman, G.R. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbank, J.C.; Pynsent, P.B. The Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000, 25, 2940–2952; discussion 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, J. Un instrumento para evaluar la eficacia de los procedimientos de inducción de estado de ánimo: “La escala de valoración del estado de ánimo” (EVEA). Anál. Modif. Conducta 2001, 27, 71–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gandek, B.; Ware, J.E.; Aaronson, N.K.; Apolone, G.; Bjorner, J.B.; Brazier, J.E.; Bullinger, M.; Kaasa, S.; Leplege, A.; Prieto, L.; et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1998, 51, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilagut, G.; Valderas, J.M.; Ferrer, M.; Garin, O.; López-García, E.; Alonso, J. Interpretación de los cuestionarios de salud SF-36 y SF-12 en España: Componentes físico y mental [Interpretation of SF-36 and SF-12 questionnaires in Spain: Physical and mental components]. Med. Clin. 2008, 130, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attal, N.; Perrot, S.; Fermanian, J.; Bouhassira, D. The neuropathic components of chronic low back pain: A prospective multicenter study using the DN4 Questionnaire. J. Pain 2011, 12, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.; Galvez, R.; Huelbes, S.; Insausti, J.; Bouhassira, D.; Diaz, S.; Rejas, J. Validity and reliability of the Spanish version of the DN4 (Douleur Neuropathique 4 questions) questionnaire for differential diagnosis of pain syndromes associated to a neuropathic or somatic component. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Becker, C.; Heidersdorf, S.; Drewlo, S.; de Rodriguez, S.Z.; Krämer, J.; Willburger, R.E. Efficacy of epidural perineural injections with autologous conditioned serum for lumbar radicular compression: An investigator-initiated, prospective, double-blind, reference-controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007, 32, 1803–1808, Erratum in Spine 2007, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Lopez, R.; Tsai, Y.C. A randomized double-blind controlled pilot study comparing leucocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma and corticosteroid in caudal epidural injection for complex chronic degenerative spinal pain. Pain Pract. 2020, 20, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godek, P. Use of autologous serum in treatment of lumbar radiculopathy pain: Pilot study. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2016, 18, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravi Kumar, H.S.; Goni, V.G.; Batra, Y.K. Autologous conditioned serum as a novel alternative option in the treatment of unilateral lumbar radiculopathy: A prospective study. Asian Spine J. 2015, 9, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, V.G.; Singh Jhala, S.; Gopinathan, N.R.; Behera, P.; Batra, Y.K.; Arjun, R.H.H.A.; Guled, U.; Vardhan, H. Efficacy of epidural perineural injection of autologous conditioned serum in unilateral cervical radiculopathy: A pilot study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015, 40, E915–E921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aghamohammadi, D.; Sharifi, S.; Shakouri, S.K.; Eslampour, Y.; Dolatkhah, N. Autologous conditioned serum (Orthokine) injection for treatment of classical trigeminal neuralgia: Results of a single-center case series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2022, 16, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hassanien, M.; Elawamy, A.; Kamel, E.Z.; Khalifa, W.A.; Abolfadl, G.M.; Roushdy, A.S.I.; El Zohne, R.A.; Makarem, Y.S. Perineural platelet-rich plasma for diabetic neuropathic pain: Could it make a difference? Pain Med. 2020, 21, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anitua, E.; Troya, M.; Alkhraisat, M.H. Effectiveness of platelet derivatives in neuropathic pain management: A systematic review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.; Garate, A.; Delgado, D.; Padilla, S. Platelet-rich plasma, an adjuvant biological therapy to assist peripheral nerve repair. Neural Regen. Res. 2017, 12, 47–52, Erratum in Neural Regen Res. 2017, 12, 338. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.202914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anjayani, S.; Wirohadidjojo, Y.W.; Adam, A.M.; Suwandi, D.; Seweng, A.; Amiruddin, M.D. Sensory improvement of leprosy peripheral neuropathy in patients treated with perineural injection of platelet-rich plasma. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014, 53, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.; Yoshioka, T.; Ortega, M.; Delgado, D.; Anitua, E. Ultrasound-guided platelet-rich plasma injections for the treatment of common peroneal nerve palsy associated with multiple ligament injuries of the knee. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2014, 22, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuffler, D. Platelet-rich plasma and the elimination of neuropathic pain. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 48, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Paliczak, A.; Delgado, D. Evidence-based indications of platelet-rich plasma therapy. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2020, 14, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisbie, D.D.; Kawcak, C.E.; Werpy, N.M.; Park, R.D.; Mc-Ilwraith, C.W. Clinical, biochemical, and histologic effects of intra-articular administration of autologous conditioned serum in horses with experimentally induced osteoarthritis. Am. J. Vet Res. 2007, 68, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehling, P.; Moser, C.; Frisbie, D.; McIlwraith, C.W.; Kawcak, C.E.; Krauspe, R.; Reinecke, J.A. Autologous conditioned serum in the treatment of orthopedic diseases: The orthokine therapy. BioDrugs 2007, 21, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, A.L.; Lim, M.; Doshi, T.L. Targeting cytokines for treatment of neuropathic pain. Scand. J. Pain. 2017, 17, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.J.; Mansfield, J.T.; Robinson, D.M.; Miller, B.C.; Borg-Stein, J. Regenerative Medicine for Axial and Radicular Spine-Related Pain: A Narrative Review. Pain Pract. 2020, 20, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabata, S.; Akeda, K.; Yamada, J.; Takegami, N.; Fujiwara, T.; Fujita, N.; Sudo, A. Advances in Platelet-Rich Plasma Treatment for Spinal Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kubrova, E.; Martinez Alvarez, G.A.; Her, Y.F.; Pagan-Rosado, R.; Qu, W.; D’Souza, R.S. Platelet Rich Plasma and platelet-related products in the treatment of radiculopathy—A systematic review of the literature. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moraes Ferreira Jorge, D.; Huber, S.C.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Da Fonseca, L.F.; Azzini, G.O.M.; Parada, C.; Paulus-Romero, C.; Lana, J.F.S.D. The mechanism of action between pulsed radiofrequency and orthobiologics: ¿Is there a synergistic effect? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Patient over 18 years of age, not illiterate. 2. Unilateral, mono and/or bisegmental radicular pain of a lower extremity of at least 6 months duration. 3. If you have received treatment before, at least 3 months must have passed since the last therapy received (infiltration, radiofrequency, or surgery), and the pain should persist in the same area. 4. Submit Lumbar Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Electromyography (EMG) performed concomitantly to the pain presented by the patient at the time of inclusion in the study. | 1. Refusal of the patient to participate in the study or not to sign the informed consent. 2. Allergy to intravenous iodinated contrast and/or local anesthetics. 3. Inability of the patient to maintain the prone position. 4. Systemic or local infection at the puncture site. 5. Present any of the following symptoms: atypical radiation pattern, bilateral involvement, or involvement of more than two segments or roots. 6. Concomitant pathological clinical history during the study/therapy: oncological disease, vertebral fractures, myelopathy, systemic disease, connective tissue disease, coagulation disorder, multiple sclerosis, osteomyelitis, or bone edema. 7. Pregnancy or lactation. 8. Previous treatment with placement of a spinal cord neurostimulator. 9. Previous treatment with a brain stimulator for the treatment of epilepsy or Parkinson’s disease. 10. Cardiac pacemaker carrier. 11. Patient who does not attend any of the treatment sessions for unjustified reasons. |

| Variables | ACS, N (%) | 0.9% PhS, N (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Women | 17 (50.0%) | 19 (52.8%) | 0.816 |

| Men | 17 (50.0%) | 17 (47.2%) | ||

| Pain | Lumbar sciatica | 2 (8.8%) | 2 (5.6%) | 0.933 |

| Radicular Pain | 31 (91.2%) | 34 (94.4%) | ||

| Affected extremity | RLE | 14 (41.2%) | 15 (41.7%) | 0.967 |

| LLE | 20 (58.8%) | 21 (58.3%) | ||

| Major Opioid | No | 32 (94.1%) | 35 (97.2%) | 0.522 |

| Yes | 2 (5.9%) | 1 (2.8%) | ||

| Menor Opioid | No | 26 (76.5%) | 31 (86.1%) | 0.300 |

| Yes | 8 (23.5) | 5 (13.9%) | ||

| No Opioid | No | 22 (64.7%) | 24 (66.7%) | 0.863 |

| Yes | 12 (35.3%) | 12 (33.3%) | ||

| Previous treatment with CS infiltrations | No | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.5%) | 0.130 |

| Yes | 34 (100.0%) | 34 (94.5%) | ||

| Previous treatment with PRF | No | 24 (70.6%) | 29 (80.6%) | 0.331 |

| Yes | 10 (29.4%) | 7 (19.4%) | ||

| Previous treatment with surgery | No | 27 (79.4%) | 29 (80.6%) | 0.905 |

| Yes | 7 (20.6%) | 7 (19.4%) | ||

| 30 Days | p-Value | 3 Months | p-Value | 6 Months | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACS N (%) | 0.9% PhS N (%) | ACS N (%) | 0.9% PhS N (%) | ACS N (%) | 0.9% PhS N (%) | |||||

| Burning | 0 | 12 (48.0%) | 18 (69.2%) | 0.163 | 14 (51.9%) | 17 (48.6%) | 0.144 | 9 (39.1%) | 17 (60.7%) | 0.300 |

| 1 | 11 (44.0%) | 5 (19.2%) | 8 (29.6%) | 7 (20.0%) | 7 (30.4%) | 5 (17.9%) | ||||

| 2 | 2 (8.0%) | 3 (11.5%) | 5 (18.5%) | 11 (31.4%) | 7 (30.4%) | 6 (21.4%) | ||||

| Painful cold | 0 | 22 (64.7%) | 23 (63.9%) | 0.829 | 21 (77.8%) | 27 (77.1%) | 0.930 | 18 (78.3%) | 21 (75.0%) | 0.911 |

| 1 | 5 (14.7%) | 7 (19.4%) | 5 (18.5%) | 6 (17.1%) | 4 (17.4%) | 5 (17.9%) | ||||

| 2 | 7 (20.6%) | 6 (16.7%) | 1 (3.7%) | 2 (5.7%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (7.1%) | ||||

| Electric discharge | 0 | 9 (29.0%) | 11 (30.6%) | 0.282 | 8 (29.6%) | 9 (25.7%) | 0.555 | 8 (34.8%) | 8 (28.6%) | 0.824 |

| 1 | 13 (41.9%) | 9 (25.0%) | 11 (40.7%) | 11 (31.4%) | 10 (43.5%) | 12 (42.9%) | ||||

| 2 | 9 (29.0%) | 16 (44.4%) | 8 (29.6%) | 15 (42.9%) | 5 (21.7%) | 8 (28.6%) | ||||

| Tingle | 0 | 6 (19.4%) | 7 (19.4%) | 0.005 ** | 5 (18.5%) | 7 (20.6%) | 0.540 | 4 (17.4%) | 6 (21.4%) | 0.915 |

| 1 | 17 (54.8%) | 7 (19.4%) | 8 (29.6%) | 6 (17.6%) | 8 (34.8%) | 10 (35.7%) | ||||

| 2 | 8 (25.8%) | 22 (61.1%) | 14 (51.9%) | 21 (61.8%) | 11 (47.8%) | 12 (42.9%) | ||||

| Pricks | 0 | 7 (22.6%) | 14 (38.9%) | 0.002 ** | 5 (18.5%) | 11 (31.4%) | 0.061 | 6 (26.1%) | 11 (39.3%) | 0.610 |

| 1 | 18 (58.1%) | 6 (16.7%) | 12 (44.4%) | 6 (17.1%) | 5 (21.7%) | 5 (17.9%) | ||||

| 2 | 6 (19.4%) | 16 (44.4%) | 10 (37.0%) | 18 (51.4%) | 12 (52.2%) | 12 (42.9%) | ||||

| Numbness | 0 | 9 (29.0%) | 3 (8.3%) | <0.001 *** | 7 (25.9%) | 4 (11.4%) | 0.266 | 8 (34.8%) | 5 (17.9%) | 0.385 |

| 1 | 17 (54.8%) | 8 (22.2%) | 9 (33.3%) | 17 (48.6%) | 8 (34.8%) | 12 (42.9%) | ||||

| 2 | 5 (16.1%) | 25 (69.4%) | 11 (40.7%) | 14 (40.0%) | 7 (30.4%) | 11 (39.3%) | ||||

| Sting | 0 | 25 (80.6%) | 17 (47.2%) | 0.002 ** | 21 (77.8%) | 25 (71.4%) | 0.792 | 17 (73.9%) | 18 (64.3%) | 0.709 |

| 1 | 4 (12.9%) | 3 (8.3%) | 3 (11.1%) | 4 (11.4%) | 3 (13.0%) | 4 (14.3%) | ||||

| 2 | 2 (6.5%) | 16 (44.4%) | 3 (11.1%) | 6 (17.1%) | 3 (13.0%) | 6 (21.4%) | ||||

| Hypoesthesia to touch | 0 | 7 (22.6%) | 7 (19.4%) | 0.007 ** | 4 (14.8%) | 10 (28.6%) | 0.367 | 5 (21.7%) | 8 (28.6%) | 0.763 |

| 1 | 17 (54.8%) | 8 (22.2%) | 13 (48.1%) | 12 (34.3%) | 13 (56.5%) | 13 (46.4%) | ||||

| 2 | 7 (22.6%) | 21 (58.3%) | 10 (37.0%) | 13 (37.1%) | 5 (21.7%) | 7 (25.0%) | ||||

| Hypoesthesia to pinprick | 0 | 13 (41.9%) | 12 (33.3%) | 0.394 | 15 (55.6%) | 19 (54.3%) | 0.174 | 14 (60.9%) | 16 (57.1%) | 0.702 |

| 1 | 10 (32.3%) | 9 (25.0%) | 12 (44.4%) | 12 (34.3%) | 8 (34.8%) | 9 (32.1%) | ||||

| 2 | 8 (25.8%) | 15 (41.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (11.4%) | 1 (4.3%) | 3 (10.7%) | ||||

| Pain on rubbing | 0 | 25 (80.6%) | 21 (58.3%) | 0.110 | 21 (77.8%) | 25 (71.4%) | 0.696 | 19 (82.6%) | 21 (75.0%) | 0.786 |

| 1 | 4 (12.9%) | 7 (19.4%) | 4 (14.8%) | 5 (14.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | 4 (14.3%) | ||||

| 2 | 2 (6.5%) | 8 (22.2%) | 2 (7.4%) | 5 (14.3%) | 2 (8.7%) | 3 (10.7%) | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Homs, M.; Milà, R.; Recasens, J.; Delgado, D.; Borràs, R.M.; Valdés, R.; Parés, D. Efficacy of Autologous Conditioned Serum on the Dorsal Root Ganglion in Patients with Chronic Radicular Pain: Prospective Randomized Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Clinical Trial (RADISAC Trial). J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7771. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217771

Homs M, Milà R, Recasens J, Delgado D, Borràs RM, Valdés R, Parés D. Efficacy of Autologous Conditioned Serum on the Dorsal Root Ganglion in Patients with Chronic Radicular Pain: Prospective Randomized Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Clinical Trial (RADISAC Trial). Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(21):7771. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217771

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoms, Marta, Raimon Milà, Jordi Recasens, Diego Delgado, Rosa Maria Borràs, Ricard Valdés, and David Parés. 2025. "Efficacy of Autologous Conditioned Serum on the Dorsal Root Ganglion in Patients with Chronic Radicular Pain: Prospective Randomized Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Clinical Trial (RADISAC Trial)" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 21: 7771. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217771

APA StyleHoms, M., Milà, R., Recasens, J., Delgado, D., Borràs, R. M., Valdés, R., & Parés, D. (2025). Efficacy of Autologous Conditioned Serum on the Dorsal Root Ganglion in Patients with Chronic Radicular Pain: Prospective Randomized Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Clinical Trial (RADISAC Trial). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(21), 7771. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14217771