Abstract

In recent years, the concepts of human resource management (HRM) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) have gained significant focus across industries. The role and implications of CSR are vital for organizational success; similarly, HRM plays a vital role in understanding, developing, and implementing CSR strategies. Therefore, we claimed that the nexus of HRM and CSR is worthwhile to study and relevant in the current pandemic situation. Despite recent calls about the role of human resource management (HRM) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in achieving sustainable performance, a few studies have investigated their role combinedly in the hospitality industry, especially in a cross-cultural context. Therefore, the present study addresses the current lack of comparative research about the impact of HRM and CSR on sustainable performance in the hospitality industry of Pakistan, the UK, and Italy and shows the mediating role of HRM in such a relationship. A quantitative methodology is applied to the survey of the employees from 354 Pakistani, 438 British, and 520 Italian hotels working in three-, four-, and five-star hotels. The results showed a positive correlation between CSR, HRM, and sustainable performance. Moreover, the results also indicated significant differences among the three countries analyzed concerning the mediating role of HRM in this relationship.

1. Introduction

The hospitality industry is amongst the prominent industries list that have grown significantly and contributed to the world’s GDP [1,2]. The World Tourism Organization of the United Nations confirmed, in 2019, the spur of tourism worldwide and its role in economic development, but COVID-19 badly hit the industry’s growth in 2020. Bartik et al. [3] claimed that the world’s economy has collapsed within a few months due to the pandemic. Other than the pandemic, the hospitality industry is also facing considerable pressures from different stakeholders to pay attention [4,5,6,7] to its adverse impact on the economic, social, and natural environments, such as water consumption, waste generation, biodiversity loss, noise pollution, air pollution, climate change, etc.

Since the hospitality industry is amongst the top contributors to the economy, it also has adverse impacts on society and the environment [8]. With the intense competition, rise in environmentally conscious consumers, and changing ecological situations, the reconfiguration ability in hotels is also becoming challenging to achieve higher performance. Apart from these pressing issues, the hospitality sector is also working on CSR-related initiatives such as responsible production, clean energy, society well-being, and poverty reduction. Therefore, understanding the role of CSR in the hospitality industry and the process of how the hotel industry is preparing CSR-related strategies has paramount importance for academicians and practitioners alike.

Different studies [9,10,11,12] argue that corporate social responsibility (CSR) has significant importance in the hospitality industry. CSR studies call upon hospitality firms to understand environmental and social issues and to be committed to eco-friendly practices through strategies and their implementation [13]. The practical implementation is only possible by engaging employees in CSR’s day-to-day practices and activities [14,15] as they are considered the primary CSR stakeholder [16]. The recent call for studies asks for more empirical studies that examine the employees’ role in formulating CSR strategies and their subsequent impact on their behaviors [9,17]. It is believed that human resource management (HRM) is a vital aspect within an organization that guides employees about the values of CSR [18], directs them in implementing CSR programs strategically to get a competitive advantage [19], and promotes an ethical culture in the whole organization [20,21]. Besides designing and implementing CSR strategies, HRM also leads the organizations to achieve environmental, social, and economic results referred to as sustainable performance [17,22,23].

Still, despite the increased importance of research about HRM–CSR nexus, scant literature is available on this relationship [24,25] in supporting CSR translation into behaviors, objectives, and actions to pursue sustainable performance (SP). Indeed, this connection has been overlooked or widely ignored, and there is a significant scarcity of empirical results that established a CSR–HRM–SP relationship [14,17].

Based on these considerations, the main objective of the present study is to enhance the understanding of the role of HRM in CSR practices and SP in the hospitality industry. The hospitality industry is an economic sector where HRM can be considered the unique and most valuable asset [26]. Indeed, the hospitality industry’s success is undeniable without the capabilities and effectiveness of human resources [27]. To achieve the strategic objective of CSR, organizations need to integrate social responsibility within the organization and push employees for their involvement and commitment [28,29]. Accordingly, this study is among the first studies to indicate the actual positioning of HRM to integrate and support CSR-rated initiatives [14,17,29,30].

This study fills a significant gap in demonstrating that HRM contributes to designing and implementing CSR programs. Very few studies unveil the potential role of HRM in the context of CSR and SP [31]. The present work considers the following research questions:

- Does HRM play a crucial role in promoting CSR in the hospitality industry of three culturally different countries?

- What practices lead managers and employees to take on socially responsible behavior to achieve sustainable performance?

- Are the practices equivalent in all the countries analyzed?

- Does HRM mediate the relationships of CSR and SP in the hospitality industry?

The research examined the HRM and CSR practices toward SP among three-, four-, and five-star hotels in Pakistan, Italy, and the UK to address these questions. The study used a methodological approach based on quantitative analysis. Using a stratified random sampling technique, the data were collected from 354 Pakistani, 437 British, and 520 Italian hotels. Additionally, the reason for choosing these countries was economic differences. Italy and the United Kingdom are considered developed economies, whereas Pakistan usually ranks as a third-world country in under-developed country statistics. The present work targets three-, four-, and five-star hotels in these countries because the larger and more luxurious hotels tend to contribute to CSR activities [32].

The following section explains the literature and background of this research, which explores the role of HRM in CSR practices and SP in the hospitality industry. Section 3 reviews the research methodology employed in this study to explore the research questions. Section 4 shows how data were collected, analyzed, and discussed, and Section 5 includes some conclusions, implications, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

In this research, we investigate the nexus of HRM–CSR–SP relationship based on social identity theory [33], as it is considered as a strong theoretical foundation to understand the employees’ role in CSR initiatives in an organization [34,35]. Referring to previous literature, we argue that when an employee perceives that their organization is engaging them in policy formulation they will push themselves to participate.

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility

García-Sánchez and Araújo-Bernardo [36] referred to CSR as an organizational responsibility to consider their environmental and social commitments rather than focusing on pure economic goals. CSR is also defined as a business strategy to achieve social, environmental, and economic sustainable development [24]. In the hospitality industry, the adoption of CSR-related initiatives provides financial benefits to the stakeholders [37].

Researchers [38,39] argued that the formation and implementation of CSR-related strategies are highly dependent on the organizational mission and the employees’ mindset. We believe that CSR should be part of organizational policies rather than considering it a part-time or philanthropic activity by involving the employees of all levels. Inyang et al. [30] also claimed that CSR strategy development and implementation is only possible by keen top management and employees themselves.

2.2. Human Resource Management

The hospitality industry creates numerous employment opportunities, and the availability of trained and skilled employees is a crucial element in a business’s success. Therefore, HRM is one of the most significant operations in the tourism sector. HRM acts as a change agent in CSR implementation [28] and plays a significant role in developing competencies to achieve SP (economic, environmental, and social performance). Indeed, the literature on the HRM–CSR relationship supports developing and managing CSR initiatives through HRM [22].

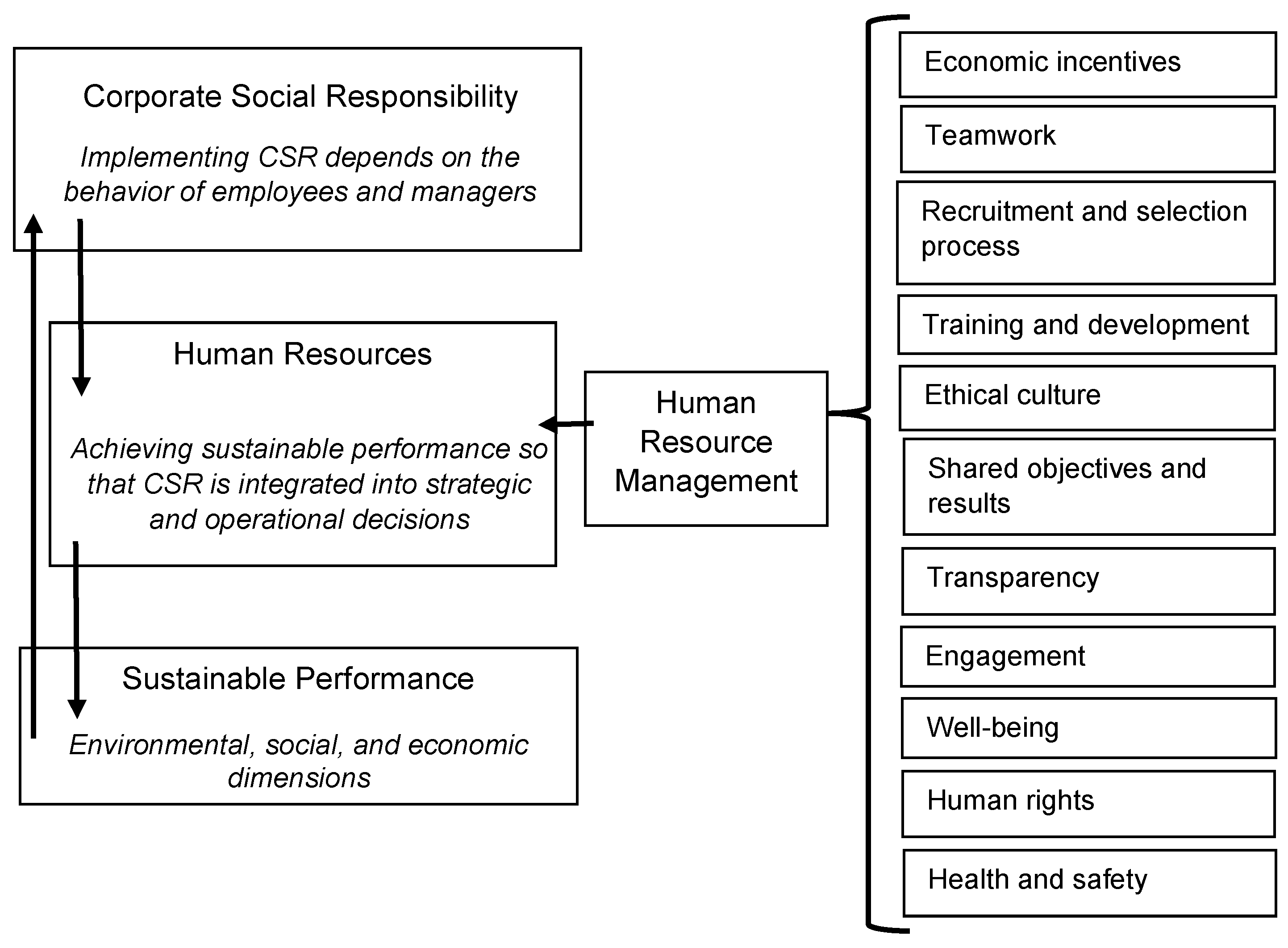

HRM is also a significant predictor of organizational performance, productivity, and individual work attitudes and behaviors [40] in achieving sustainable competitive advantage [41]. Aligning CSR strategies in the organizational operations requires support from HRM practices [24,42,43] to achieve SP (Figure 1): economic incentives; teamwork; recruitment and selection process; training and development; ethical culture; shared objectives and results; transparency; engagement; well-being; human rights; health and safety.

Figure 1.

The CSR–HRM–SP Relationship.

2.2.1. Economic Incentive

Sola and Ajayi [44] referred to economic incentives as financial or monetary benefits accrued to the employees for their work done. They were described as important tools to motivate employees for better performance in the organizations. Prior studies show that remuneration helps bring into line the interests of employees and owners associated with higher employee and organizational productivity [44].

2.2.2. Teamwork

Recently, several authors have identified extensive use of teamwork in decision-making as essential high-performance HRM practice. Teamwork has a statistically significant and positive effect on satisfaction and performance at work [45].

2.2.3. Recuritment and Selection Process

Several authors have supported that the recruitment of apposite candidates in the firms should be combined with the development of workforce effectiveness relevant to the business strategies and objectives [46]. This is consistent with the arguments of several scholars who deliberated that efficiency of selection and recruitment practices leads to high firm performance [46].

2.2.4. Training and Development

Studying the impact of different HR practices, Herrbach et al. [47] observed that the provision of training opportunities improves the competencies and expertise of employees, which sequentially boosts their efficiency and effectiveness. Proper training sessions in the organizations contribute to building a partnership between the employees and organizations, enriching their abilities, skills, knowledge, resulting in lower staff turnover [48].

2.2.5. Ethical Culture

The ethical culture consists of the job environment that can be viewed as the formal (codes of conduct, training efforts) and informal (norms concerning ethics and peer behavior) systems to enhance the workplace’s ethical behavior. Furthermore, [49] postulated that ethical organizational culture could also affect employees’ behavior and attitude and serve as a motivational factor.

2.2.6. Shared Objectives and Results

Shared objectives can positively affect performance by aligning employee efforts, shared responsibility of the results, and increased motivation [30,50]. Motivated employees are highly engaged, innovative, creative, perform all the tasks effectively and efficiently, and are attached to their organizations that significantly enhance sustainable individual and organization performance [51].

2.2.7. Transparency

Transparency is one of the most critical factors of firms that serve as a vital signal and ensures that management is not involved in unlawful activities as their activities are scrutinized. Transparency confirms that managers utilize the organization’s resources most efficiently and desirably and for the most appropriate goals without improper regard for personal interests [52].

2.2.8. Engagement

According to Armstrong [53], employee engagement is an organizational setting that provides equal opportunity to the employees to influence organizational decisions and contribute to improving organizational performance. Employee engagement is “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” [54].

2.2.9. Well-Being

Employee well-being defines as the employees’ feelings of satisfaction regarding their work environment. Demirtas et al. [55] defined it as a positive mindset, dedication, self-fulfillment, and a higher level of vigor, indicated by feelings of enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and meaningfulness of the job. Furthermore, [56] opined that sustainable performance and employee well-being had become crucial issues for sustainable organizational development.

2.2.10. Human Rights

Human rights became a matter of responsibility and duty of firms [57]. All persons must work, including equal access to productive resources, receiving wages, living adequate for well-being, and freedom from discrimination based on race, sex, or any other status, in all aspects of work.

2.2.11. Health Safety

Health and safety concerns are explained by [58] as the maintenance and promotion of the highest level of the social, mental, and physical wellbeing of the employees. This aspect is important, in particular, where the firms are operating in countries with limited or no relevant legislation.

2.3. Sustainable Performance

Rhou and Singal [37] argue that since the hospitality industry decided to adopt sustainable practices, its profitability level seems to increase and benefit its stakeholders. The previous studies examined the linkage of CSR and financial performance relationship and supported positive association among them [59]. However, the effect of CSR on other performance has rarely been examined to date. A review of 127 empirical studies published during 1997–2002 confirmed the positive role of CSR in fostering financial outcomes [60]. Overall, it is suggested that HR impacts the organizational processes, positioning CSR initiatives and increasing organizational performance [30].

CSR practices influence individuals’ learning, retention, liability, morale, motivation, and productivity, increasing loyalty, commitment, and organizational performance [61,62,63]. The integration of CSR goals and values also inspires staff satisfaction, improves communication among employees, social involvement, stakeholder engagement, fosters ethical standards, lowers absenteeism, strengthens loyalty, transparency, and increases performance [19,64,65,66].

According to Milfelner et al. [67], the main concern of HRM is to motivate, support, and manage the workforce to achieve organizational performance and hold them responsible for different actions within the organization. HRM plays an essential role in influencing how a firm employs its resources to accomplish environmental, social, and financial performance [21,66,68] in line with the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations’ 2030 Agenda. Table 1 indicates different performance indicators.

Table 1.

Sustainable performance indicators for the hospitality industry.

Researchers argued that CSR has significant importance in the hospitality industry, and HRM is critical in educating firms on CSR values and leading behaviors to pursue a sustainable performance (SP). HRM plays an essential role in managing, supporting, and motivating employees to achieve the organization’s performance [17] and influence how a firm employs its resources to accomplish SP [15,21,66]. However, despite the significant contribution of CSR, HRM, and SP, a limited number of studies have jointly analyzed these aspects in the hospitality industry and the context of culturally distinct countries. A more comprehensive study is required to understand the nexus of HRM, CSR, and SP in the hospitality industry.

3. Methodology

The primary purpose of this quantitative research is to examine the CSR–HRM–SP relationship in the hospitality industry in three culturally specific countries―Italy, the UK, and Pakistan. The research used different analytical methods [69,70], including reliability tests, validity tests, correlations, multiple regression analyses, and mediating regression analysis with the help of SPSS v.20 and Hayes PROCESS [70,71].

The population of this study was three-, four-, and five-star hotels in the three aforementioned countries. The number of hotels in Italy is around 33,200, of which 24,200 are three-, four-, and five-star hotels. Around 45,000 hotels are operating in the UK, of which 12,089 fall in the three-, four-, and five-star categories. As far as Pakistani hotels are concerned, around 15,000 hotels are operational, of which 475 hotels have three, four, and five stars. The research develops a database of three-, four-, and five-star hotels for each country separately. After using a stratified random sampling technique with 95% confidence interval, 1% margin of error, and 10% of hotels that should take part, the sample of Italian hotels was 3037, British hotels were 2684, and Pakistani hotels were 475. We took all three-, four-, and five-star hotels of Pakistan because of the significant reduction in the size of this sample concerning the other two countries. The advantage of using a probability sampling technique is that the results can be easily generalized across the population with a significant confidence interval. After six weeks of waiting, we received the questionnaires from 520 Italian hotels (17% response rate), 354 Pakistani hotels (75% response rate), and 438 British hotels (16% response rate). Hence, a total of 1312 questionnaires were received from all countries. The data collection phase was started in February 2020 till September 2020.

A highly structured questionnaire was designed through Google Forms in English and Italian and was forwarded to the mailing list of randomly selected hotels from each country. The main purpose of analyzing reliability and validity in the pilot study is to understand whether any different perceptions prevail in three culturally-distinct countries regarding HRM and CSR. The measuring instruments of each variable were extracted from previous literature and adopted according to the need of this research. The CSR-related activities in the hospitality industry were measured using 9 items and included hotel concerns on social, environmental, and economic dimensions. In contrast, the HRM practices were measured with 14 items, including economic incentives, human rights, training and development, well-being, engagement, ethical culture, health and safety, recruitment and selection process, teamwork, transparency, shared objectives, and results. The SP was measured using 7 items (social, environmental, and economic performance). All items were measured on a 1 to 7 Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. The questionnaire also asked the hotel details, including the number of rooms and the hotel category/star. Additionally, the questionnaire asked the respondent demographic profile: gender, position, experience in the current hotel, and total hotel industry experience.

3.1. Hotel Characteristics

Table 2 shows the hotel sample features. We observe that 40% of hotels are from Italy, 33% from the UK, and 27% from Pakistan. In the hotel category, 55% of hotels have a 3-star category, 38% have 4-stars, and only 7% have a five-star category. Most of the hotels (51%) have 21–50 rooms, whereas only 6% have 100 + rooms. Around 37% of hotels have been operational between 11 and 20 years, while 52% have employees ranging from 10 to 49.

Table 2.

Hotel Sample Characteristics.

3.2. Demographic Profile

Table 3 shows the demographic profile of the respondents. The table shows that 35% of respondents were female, and 65% of them were male. In the age category, 50% had ages between 36 and 45 years, while 24% were between 26 and 35 years of age, and 22% belonged to the 46–60 year of age bracket. Around 56% of respondents were working on managerial rank, 21% were Chief Executive Officers, and 4% were owners of hotels. As far as experience in the current position is concerned, 41% of respondents had been working in the same position for 4 to 6 years, while 42% had been working for 7 to 9 years in their current position. Moreover, 48% of respondents had been for 7 to 9 years in the hotel where they were working, while 35% had experience of 4 to 6 years in the same hotel.

Table 3.

Characteristics of Respondents in the Sample.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, we present the results of the empirical application. Table 4 shows the reliabilities of HRM, CSR, and SP in the hotel industries of Italy, the UK, and Pakistan. As indicated, the reliability of HRM, CSR, and SP is well above the threshold of 0.70 proposed by Hair et al. [72].

Table 4.

Cronbach’s Alpha Tests for Reliability-Composite Data.

Table 5 lists the descriptive statistics of HRM, CSR, and sustainable performance for all the analyzed countries. The confirmatory factor analysis was performed to determine the psychometric properties of the variables used in the study. The results show acceptable model fitness (χ2/df = 1451.2/709; p < 0.01, CFI = 0.955, NFI = 0.949, NNFI = 0.940, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.048). The factor loading of each item is greater than 0.50. The average variance extraction (AVE) is greater than 0.50, whereas the composite reliability ranges from 0.84 to 0.89. All these statistics indicate the strong support to the reliability, and validity (59) of HRM, CSR, and sustainable performance.

Table 5.

Descriptive Results.

Table 6 explores the correlations between each HRM practice with CSR and sustainable performance for in-depth results. The results show that HRM is strongly correlated with CSR in the UK (r = 0.50, p = 0.001), followed by Italy (r = 0.48, p = 0.001) and Pakistan (r = 0.47, p = 0.001). Similarly, HRM is strongly correlated with sustainable performance in the UK (r = 0.42, p = 0.001), followed by Pakistan (r = 0.40, p = 0.001) and Italy (r = 0.33, p = 0.001). Lastly, CSR has stronger relationship with sustainable performance in Pakistan (r = 0.66, p = 0.001), followed by the UK (r = 0.65, p = 0.001) and Italy (r = 0.63, p = 0.001). The correlation analyses were also conducted for each HRM practice with CSR and sustainable performance separately (Table 7). The HRM practices include ethical culture, engagement, human rights, training and development, economic incentives, transparency, well-being, teamwork, recruitment and selection process, health and safety, and shared objectives and results.

Table 6.

Correlation Results.

Table 7.

HRM Individual Practices.

Table 7 indicates the correlations of individual HRM practices with CSR and SP. With respect to Pakistani results, economic incentives (r = 0.50, p = 0.001), recruitment and selection process (r = 0.40, p = 0.001), and teamwork (r = 0.39, p = 0.001) have higher correlation with CSR as compared to other HRM aspects, while economic incentives (r = 0.57, p = 0.001) has strong correlation with sustainable performance, followed by recruitment and selection process, and ethical culture. For the British sample, economic incentives (r = 0.52, p = 0.001), recruitment and selection process (r = 0.44, p = 0.001), and ethical culture (r = 0.38, p = 0.001) have higher correlation with CSR, whereas economic incentives (r = 0.67, p = 0.001) strongly correlates with sustainable performance, followed by ethical culture and shared objectives and results. For the Italian data, economic incentives are strongly related to CSR (r = 0.47, p = 0.001), followed by teamwork and ethical culture. Similarly, ethical culture has a stronger relationship with sustainable performance (r = 0.46, p = 0.001), followed by human rights and engagement.

Table 8 shows the multiple regression analysis, where HRM was regressed on CSR. In the Pakistani sample, HRM scores 31% of variance in explaining the dependent variable, with a significant F statistics (F = 97.662, p > 0.07). The results highlight that HRM does not have a significant and positive impact on CSR (beta = 0.229, t = 0.538, p > 0.07, CI = −0.0346 to 0.2363). In the British sample, HRM totals 31% of variance in explaining the dependent variable, with a significant F statistics (F = 97.782, p = 0.001). The results highlight that HRM has a significant and positive impact on CSR (beta = 0.3174, t = 3.964, p = 0.001, CI = 0.2512 to 0.3146). In the Italian sample, HRM reaches 29% of variance in explaining the dependent variable, with a significant F statistics (F = 104.006, p = 0.001). The results highlight that HRM has a significant and positive impact on CSR (beta = 0.19, t = 3.824, p = 0.001).

Table 8.

Multiple Regression Analysis.

Lastly, Table 9 indicates the indirect impact of HRM on SP in the presence of CSR. In the Pakistani sample, the results highlight that the indirect role of CSR between HRM-SP relationships is insignificant (CI 95%: −0.0020, 0.1184). Similarly, no mediation is found in the Italian sample (CI 95%: −0.0288., 0.0825), while the mediating role of CSR is confirmed in the UK sample (CI 95%: 0.2481, 0.4687).

Table 9.

Bootstrap Results of the Mediation Model.

5. Conclusions

The present study contributes to the development of the HRM practices by analyzing their connection to CSR and their impact on sustainable performance by presenting a quantitative (survey) analysis. The results show that HRM is correlated with CSR in the UK, Italy, and Pakistan and that economic incentives, ethical culture, and teamwork play an important role in enhancing sustainable performance in the three countries. At the same time, economic incentives have a relatively stronger impact on CSR in the British hospitality industry than the Italian and Pakistan hotels. This result supports the findings by Sola and Ajayi [44] that compensation is one of the essential aspects of managerial practices.

Results of correlation between HRM practices and sustainable performance show that ethical culture in the Italian hospitality industry has a relatively stronger impact on sustainable performance than the British and Pakistani hotels. However, in the Pakistani and British hospitality context, economic incentives serve as a powerful practice to enhance sustainable performance. The findings of this study suggest that HRM contributed to developing and promoting CSR in the hospitality industry in the UK and Italy. In contrast, Pakistani hotels showed that HRM does not have a significant and positive impact on CSR.

Furthermore, the mediation analysis reveals that HRM has a stronger influence on the relationship between CSR and SP in the British hospitality industry. This standpoint regarding the British sample is in line with previous research [23,62] that stated that HRM could facilitate CSR objectives by developing a CSR culture and embedding CSR values into social norms, providing a ground for developing SP. As the results imply, the UK has a relatively stronger impact on CSR because of written policies, corporate governance mechanisms, internal and external stakeholders’ pressures, compared to structures in Pakistan and Italy. This result endorses the standpoint of Jamali et al. and Podgorodnichenko et al. [22,23]. They claim that effective integration of HRM and CSR would generate sustainable outcomes, since HRM is a strategic position in strengthening CSR initiatives aligned with an organization’s visions and goals.

The results from the British quantitative analysis have given rise to the view that HRM policies and strategies in the hospitality industry have a significant influence on the effects of CSR practices and SP observed in this study. Drawing on the above results from the British analysis, it can be indicated that hospitality firms engaged heavier in CSR activities should also have developed HRM strategies, which can be stated as CSR-related HRM practices, to achieve SP and to be sustainable in the society. Therefore, HRM plays a mediation role in this relationship.

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

The previous literature investigates the HRM and CSR role in achieving sustainable performance, and our results are consistent with such studies [16,73,74,75]. However, scant literature exists to understand the impact of HRM and CSR in achieving sustainable performance in the hospitality industry, especially in a cross-cultural context. Previous studies identified that the focus of HRM is on employee well-being, performance, and ethical concerns [16,76], but have hardly investigated its relationship with CSR, excepting a few. Additionally, this study attempts to provide a broader perspective of HRM and its impact on CSR.

Moreover, the current study also addresses the call for multilevel studies in understanding the company’s overall perception about socially responsible behavior and the process behind fostering such behaviors by the HR department [77,78]. Although previous studies have examined the positive role of CSR on performance, the role of HRM in shaping CSR and their subsequent behavior in achieving sustainable performance in a cross-cultural context has rarely been studied. Moreover, different studies [79,80] identified mixed results, but this study indicates that HRM is a relatively stronger impact on western cultures. Therefore, these results open new avenues for future studies and contribute to examining the HRM–CSR-performance nexus, especially in the hospitality industry.

5.2. Managerial Implications

These firms should be engaged in responsible employee involvement and well-being, recruitment, training, and career management practices; better definition of training needs; employee satisfaction; and motivation practices. These practices allow the firm to translate CSR into behaviors, objectives, and actions to pursue SP [7]. Whereas, in the presence of HRM, CSR does not show any role in the resulting SP in Pakistani and Italian contexts. Considering the overwhelming results of our study, it is essential for the hotel management to fully utilize the HR department in proposing, developing, and implementing CSR initiatives for achieving sustainable performance. Therefore, more effort is requested towards HR practices such as economic incentives and recruitment procedures to implement CSR practices fully. At the same time, ethical culture and transparency are significant determinants that influence sustainable performance in the hospitality industry.

5.3. Limitations and Avenues for Future Studies

Among various theoretical and managerial implications, this study also has limitations that open avenues for future studies. For instance, this study was cross-sectional; therefore, future researchers should infer the causality carefully and replicate the model with a longitudinal research design. Second, the data were collected from three, four, and five-star hotels from the UK, Pakistan, and Italy. We propose that future studies should also consider small and medium hotels, along with resorts. Lastly, we collected the data from one respondent of each hotel, which may provide a biased result. Hence, a multi-respondent strategy should be adopted to obtain more holistic HRM, CSR, and sustainable performance results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.F.; formal analysis, H.S. and M.I.I.; methodology, S.F., M.I.I. and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.F. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, M.I.I. and S.F.; visualization, S.F., M.I.I. and H.S.; supervision, S.F.; project administration, S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

A survey questionnaire was designed on Google Form in both English and Italian language and forward to mailing list of randomly selected hotels from each Country. Data can be obtained through email at h.sarwar@unibs.it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hwang, J.; Lee, J. A strategy for enhancing senior tourists’ well-being perception: Focusing on the experience economy. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 36, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.S.; Hou, F.; Kim, W.G.; Ahmad, W.; Ashraf, R.U. Modeling tourists’ visiting intentions toward ecofriendly destinations: Implications for sustainable tourism operators. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 29, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, A.W.; Bertrand, M.; Cullen, Z.B.; Glaeser, E.L.; Luca, M.; Stanton, C.T. How Are Small Businesses Adjusting to COVID-19? Early Evidence from a Survey; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, N.T.; Tučková, Z.; Jabbour, C.; Chiappetta, J. Greening the hospitality industry: How do green human resource management practices influence organizational citizenship behavior in hotels? A mixed-methods study. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, D. Environmental management in hotels. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. 1995, 7, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Green image and consumers’ word-of-mouth intention in the green hotel industry: The moderating effect of Millennials. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 181, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, H.; Ishaq, M.I.; Amin, A.; Ahmed, R. Ethical leadership, work engagement, employees’ well-being, and performance: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 2008–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohdanowicz, P.; Zientara, P. Hotel companies’ contribution to improving the quality of life of local communities and the well-being of their employees. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Zhang, H. Being sustainable: The three-way interactive effects of CSR, green human resource management, and responsible leadership on employee green behavior and task performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 28, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Hua, N.; Lee, S. Does size matter? Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Grosbois, D. Corporate social responsibility reporting by the global hotel industry: Commitment, initiatives and performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 896–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tate, W.L.; Bals, L. Achieving shared triple bottom line (TBL) value creation: Toward a social resource-based view (SRBV) of the firm. J. Bus. Ethics. 2018, 3, 803–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvaiya, H.; Eweje, G.; Arrowsmith, J. The roles of HRM in CSR: Strategic partnership or operational support? J. Bus. Ethics. 2018, 3, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, S. Measuring Corporate Culture. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2013, 4, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.; Vithayathil, J.; Yim, D. Are corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives such as sustainable development and environmental policies value enhancing or window dressing? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Ardichvili, A. Examining the Link Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Human Resources: Implications for HRD Research and Practice. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 2, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, E. A review of corporate social responsibility in developed and developing nations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvaiya, H.; Arrowsmith, J.; Eweje, G. Exploring HRM involvement in CSR: Variation of Ulrich’s HR roles by organisational context. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 32, 4429–4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chams, N.; García-Blandón, J. On the importance of sustainable human resource management for the adoption of sustainable development goals. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 141, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.R.; El Dirani, A.M.; Harwood, I.A. Exploring human resource management roles in corporate social responsibility: The CSR-HRM co-creation model. Bus. Ethics. 2015, 2, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgorodnichenko, N.; Edgar, F.; McAndrew, I. The role of HRM in developing sustainable organizations: Contemporary challenges and contradictions. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 3, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.P.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K.; Igalens, J. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 2018, 2, 619–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VoeVoegtlin, C.; Greenwood, M. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: A systematic review and conceptual analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nieves, J.; Quintana, A. Human resource practices and innovation in the hotel industry: The mediating role of human capital. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 18, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kesgin, M.; Hsieh, Y.-C.; Al Qusayer, A. What motivates and satisfies lodging employees in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia? J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 19, 388–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, H.; Khare, A. HR’s crucial role for successful CSR. J. Bus. Ethics. 2010, 2, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yusliza, M.-Y.; Norazmi, N.A.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Fernando, Y.; Fawehinmi, O.; Seles, B.M.R.P. Top management commitment, corporate social responsibility and green human resource management. Benchmarking Int. J. 2019, 26, 2051–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, B.J.; Awa, H.O.; Enuoh, R.O. CSR-HRM nexus: Defining the role engagement of the human resources professionals. Int. j. bus. soc. 2011, 5, 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, F.; Bagdadli, S.; Camuffo, A. The HR role in corporate social responsibility and sustainability: A boundary-shifting literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 57, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Wattanakamolchai, S.; Perdue, R.R.; Calvert, E.O. Corporate Social Responsibility Within the U.S. Lodging Industry: An Exploratory Study. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2009, 33, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Justice in Social Exchange. Sociol. Inq. 1964, 34, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behaviour. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 2nd ed.; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Goldman, B.M.; Benson, L.I. Organizational justice. In Handbook of work stress; Barling, J., Kelloway, E.K., Frone, M.R., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, I.; Araújo-Bernardo, C. What colour is the corporate social responsibility report? Structural visual rhetoric, impression management strategies, and stakeholder engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 1117–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhou, Y.; Singal, M. A review of the business case for CSR in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 84, 102330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, R.; Watson, R.T.; Hasan, H.; Molla, A.; Bjorn-Andersen, N. Information systems solutions for environmental sustainability: How can we do more? J. Assoc. Inf. 2016, 8, 521–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Helo, P.; Papadopoulos, T.; Childe, S.J.; Sahay, B.S. Explaining the impact of reconfigurable manufacturing systems on environmental performance: The role of top management and organizational culture. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Huang, X.; Tang, D.; Yang, J.; Wu, L. How guanxi HRM practice relates to emotional exhaustion and job performance: The moderating role of individual pay for performance. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 32, 2493–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh, H.K.; Mansour, M.H. Role of Knowledge Processes as a Mediator Variable in Relationship between Strategic Management of Human Resources and Achieving Competitive Advantage in Banks Operating in Jordan. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, V.; Arora, B. Examining HRM and CSR linkages in the context of emerging economies: The Indian experience and book of Human Resource Management in Emerging Markets; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015.

- Aust, I.; Matthews, B.; Muller-Camen, M. Common Good HRM: A paradigm shift in Sustainable HRM? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 30, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, A.; Ajayi, W. Personnel management and organizational behavior; Evi Coleman Publication: Ibadan, Nigeria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ehnert, I.; Parsa, S.; Roper, I.; Wagner, M.; Muller-Camen, M. Reporting on sustainability and HRM: A comparative study of sustainability reporting practices by the world’s largest companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 1, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayson, S.; Barret, R. The ‘science’ and ‘practices’ of human resources management in small firms. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2006, 4, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Herrbach, O.; Mignonac, K.; Vandenberghe, C.; Negrini, A. Perceived human resourcemanagement practices, organizational commitment and voluntary early retirement amonglate-career managers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 48, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrena-Martinez, J.; López-Fernández, M.; Romero-Fernandez, P.M. Socially responsible human resource policies and practices: Academic and professional validation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maamari, B.E.; Majdalani, J.F. Emotional intelligence, leadership style and organizational climate. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2017, 2, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michailides, T.P.; Lipsett, M.G. Surveying employee attitudes on corporate social responsibility at the frontline level of an energy transportation company. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 5, 296–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, T.; Ye, M. Studying on the impact of perceived over qualification on work engagement: The moderating role of future work self salience and mediating role of thriving at work. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ugarte, S.M.; Rubery, J. Gender pay equity: Exploring the impact of formal, consistent and transparent human resource management practices and information. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 31, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice, 10th ed.; Kogan Page Publishing: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job Demands, Job Resources, and Their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study. Available online: https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/209.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Demirtas, O.; Hannah, S.T.; Gok, K.; Arslan, A.; Capar, N. The Moderated Influence of Ethical Leadership, Via MeaningfulWork, on Followers’ Engagement, Organizational Identification, and Envy. J. Bus. Ethics. 2017, 145, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting Well-Being, Meaningfulness, and Sustainability in Organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Voices of Suffering, Fragmented Universality, and the Future of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/8134847/_1998_Voices_of_Suffering_and_the_Future_of_Human_Rights_Transnational_Law_and_Contemporary_Problems_Fall_1998_pp_125_169 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Reese, C.D. Occupational health and safety management: A practical approach; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.P. Misery Loves Companies: Rethinking Social Initiatives by Business. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 268–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, S.E.; Schuler, R.S.; Jiang, K. An aspirational framework for strategic human resource management. Acad. Manag. Anal. 2014, 8, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, F.L.; He, Q. Corporate social responsibility and HRM in China: A study of textile and apparel enterprises. Asia Pacific Busin. Rev. 2010, 16, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Varriale, L. Management innovation for environmental sustainability in seaports: Managerial accounting instruments and training for competitive green ports beyond the regulations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Sanchez-Hernandez, M.I. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility for competitive success at a regional level. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, L.; Haunschild, A.; Matten, D. The rise of CSR: Implications for HRM and employee representation. The Inter. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2009, 20, 953–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, A.; Varriale, L. SDGs and airport sustainable performance: Evidence from Italy on organisational, accounting and reporting practices through financial and non-financial disclosure. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 249, 119431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfelner, B.; Potočnik, A.; Žižek, S.Š. Social responsibility, human resource management and organizational performance. Sys. resear. behave. scien. 2015, 32, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, S. Measuring the sustainability performance of the tourism sector. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnacchiaro, P.; Boccia, F. Some remarks on measurement models in the structural equation model: An application for socially responsible food consumption. J. Appl. Stat. 2018, 45, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Rockwood, N.J. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 98, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 6, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Yusoff, Y.M. Green human resource management. Int. J. Manpow. 2020, 7, 1041–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.; Morales-Sánchez, R.; Pasamar, S. Mapping the Link between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Human Resource Management (HRM): How Is This Relationship Measured? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Otoo, F.N.K. Human resource management (HRM) practices and organizational performance. The mediating role of employee competencies. Employee Relations. Int. J. 2018, 41, 949–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Delobbe, N. Do Environmental CSR Initiatives Serve Organizations’ Legitimacy in the Oil Industry? Exploring Employees’ Reactions Through Organizational Identification Theory. J. Bus. Eth. 2012, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. .J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Farooq, O.; Cheffi, W. How do employees respond to the CSR initiatives of their organizations: Empirical evidence from developingcountries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, A.; Miao, Q.; Hofman, P.S.; Zhua, C.J. The impact of socially responsible human resource management onemployees’ organizational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role oforganizational identification. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 2016, 27, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).