Effects of Sustainable Brand Equity and Marketing Innovation on Market Performance in Hospitality Industry: Mediating Effects of Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainability

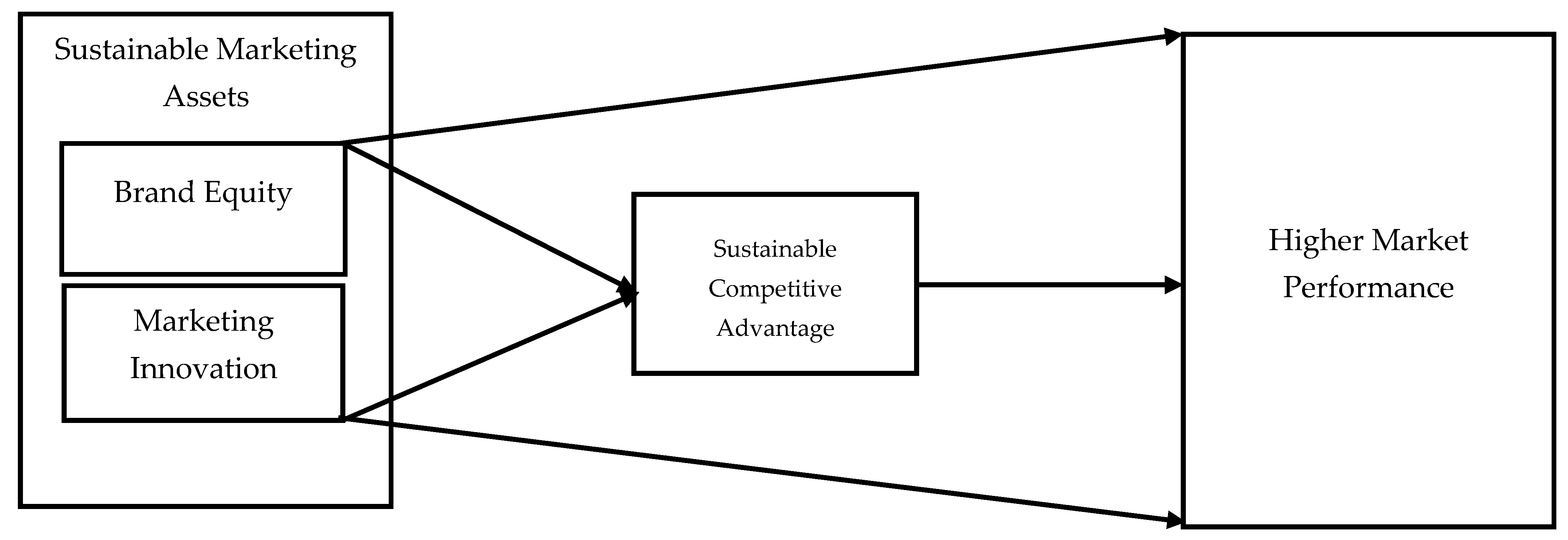

2.2. Hypotheses and Theoretical Model Development

2.2.1. Brand Equity and Sustainable Competitive Advantage

2.2.2. Marketing Innovation and Sustainable Competitive Advantage

2.2.3. Brand Equity and Market Performance

2.2.4. Marketing Innovation and Market Performance

2.2.5. Sustainable Competitive Advantage and Market Performance

2.2.6. Sustainable Competitive Advantage as a Mediator between Sustainable Marketing Assets and Market Performance

3. Research Methodology

4. Results and Interpretation

4.1. Analysis and Procedure

4.2. Preliminary Analysis

4.3. Measurement Model

4.4. Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion on Findings

6. Conclusions

- i.

- As the data was collected from customers who live in urban areas and not from rural areas, there is an issue in generalizing the findings of the current study to all customers of the whole of Pakistan. Future research may be conducted by collecting the data from both urban as well as rural areas to generalize the results of the research.

- ii.

- The research took a few selected sustainable marketing assets only. Future research can consider sustainable marketing assets such as goodwill, corporate reputation, and several others. For example, corporate reputation can have a positive effect on the market performance of attracting customers, and marketers need to take care of the corporate reputation while developing marketing strategies.

- iii.

- The sample of the current research was taken from the hospitality industry; therefore, the results of the study cannot be generalized in other sectors (industries) due to the embedded contexts, life cycles, and levels of competition in each industry (Nguyen and Papadopoulos, 2011), which might affect the investment of firms in sustainable marketing practices. In future, research should be conducted in other industries to generalize the results of the current study.

- iv.

- In the current research, only the customers of hotels/restaurants were considered, while other stakeholders, such as hotels/restaurant clients and suppliers, have been overlooked. Future research should be conducted by considering other stakeholders to understand the sustainability issues in a more comprehensive way and by implementing them properly in hotels/restaurants industry.

- v.

- Future research can also address the social, cultural, and economic difference among customers and the effects of sustainable marketing assets on them.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Study Questionnaire

Thank you for sparing some of your precious time to fill in this questionnaire. It is being distributed to you purely for academic purpose and all the responses will be confidential. Your unbiased choices will be highly appreciated and make this research valuable.

| Please indicate the appropriate choice by selection in parentheses |

| 1. Gender |

| (a) Male ( ) ; (b) Female ( ) |

| 2. Age |

| (i) 20 or less ( ) ; (ii) 21–30 ( ) ; (iii) 31–40 ( ) ; (iv) 41– 50 ( ) ; (v) 51–60 ( ) ; (vii) 60 or above ( ) |

| 3. Marital Status |

| (a) Married ( ); (b) Single ( ) |

| Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about your organization. | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 4 | It makes sense to buy XYZ instead of any other brand, even if they are the same. | |||||

| 5 | Even if another brand has same features as XYZ, I would prefer to buy XYZ. | |||||

| 6 | If there is another brand as good as XYZ, I prefer to buy XYZ. | |||||

| 7 | If another brand is not different from XYZ in any way, it seems smarter to purchase XYZ. |

| Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about your organization. | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 8 | Product related strategies are innovative in a radical way. | |||||

| 9 | Pricing strategies are innovative in a radical way. | |||||

| 10 | Promotion (advertising, sales promotion, sales force, etc.) strategies are innovative in a radical way. | |||||

| 11 | Distribution (channel, logistics, and supply chain) related strategies are innovative in a radical way. |

| Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about your organization | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neither | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 12 | The company is more capable of R&D than the competitors. | |||||

| 13 | The company has better managerial capability than the competitors. | |||||

| 14 | The quality of the products or services that the company offers is better than that of the competitors’ products or services. | |||||

| 15 | The company’s profitability is better than the competitors. | |||||

| 16 | The corporate image of the company is better than that of the competitors | |||||

| 17 | The competitors are difficult to take the place of the company’s competitive advantage. |

| Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statements about your organization | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree | |

| 18 | I am satisfied with my hotel/restaurant. | |||||

| 19 | Quality of core service is up to your expectations. | |||||

| 20 | I recommend the hotel/restaurant to friends and associates. | |||||

| 21 | I encourage friends and associates to visit this hotel/restaurant | |||||

References

- Dauvergne, P.; Lister, J. Eco-business. A Big-Brand Takeover of Sustainability/Peter Dauvergne and Jane Lister; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; New Society: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sajjad, A.; Eweje, G. Corporate social responsibility in Pakistan: Current trends and future directions. In Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability: Emerging trends in Developing Economies; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Eweje, G. Introduction: Trends in corporate social responsibility and sustainability in emerging economies. In Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability: Emerging Trends in Developing Economies; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Anisul Huq, F.; Stevenson, M.; Zorzini, M. Social sustainability in developing country suppliers: An exploratory study in the ready-made garments industry of Bangladesh. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 610–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C. CSR in developed versus developing countries: A comparative glimpse. In Research Handbook on Corporate Social Responsibility in Context; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin, M.; Mamun, A.A.; Fazal, S.A.; Masud, M.M. Environmental Knowledge, Awareness and Business School Students’ Intention to Purchase Green Vehicles in Emerging Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. Resource-Advantage Theory: An Evolutionary Theory of Competitive Firm Behavior? J. Econ. Issues 1997, 1, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, S.D. Developing successful theories in marketing: Insights from resource-advantage theory. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2011, 1, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooley, G.; Greenley, G.; Cadogan, J.; Fahy, J. The performance impact of marketing resources. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.K.; Kang, S.; Jeong, H.Y. The effect of market orientation on performance of sharing economy business: Focusing on marketing innovation and sustainable competitive advantage. Sustainability 2019, 11, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.K.; Shervani, T.A.; Fahey, L. Market-based assets and shareholder value: A framework for analysis. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of Growth of The Firm; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, P.; Nachiappan, S.; Ramanathan, R. The impact of marketing capability, operations capability and diversification strategy on performance: A resource-based view. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Gaining and Sustaining Competitive Advantage; Prentice Hall Person: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Talaja, A. Testing VRIN framework: Resource value and rareness as sources of competitive advantage and above average performance. Management 2012, 7, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Peteraf, M.A.; Bergen, M.E. Scanning dynamic competitive landscapes: A market-based and resource-based framework. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 24, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, H.; Klock, M. The relation between patent citations and Tobin’s Q in the semiconductor industry. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 1997, 9, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.W.; Lee, B.K. Effects of internal resources on airline competitiveness. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2014, 36, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, M.; Zhou, N. Capitalizing RandD expenses versus disclosing intangible information. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2016, 46, 661–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrominas, M. Recognized intangibles and the present value of growth options. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2017, 48, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davcik, N.S.; Sharma, P.; Grigoriou, N. Exploring the role of brand equity and RandD as drivers of product innovation and market performance: An abstract. In Marketing at the Confluence between Entertainment and Analytics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B.; Arikan, A.M. The resource-based view: Origins and implications. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Hitt, M.A., Freeman, R.E., Harrison, J.S., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kor, Y.; Mesko, A. “Dynamic managerial capabilities: Configuration and orchestration of top executives’ capabilities and the firm’s dominant logic”. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Childe, S.J.; Shibin, K.T.; Wamba, S.F. Sustainable supply chain management: Framework and further research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, T.; Gunasekaran, A.; Dubey, R.; Fosso Wamba, S.; Childe, S.J. World Class Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Critical review and further research directions. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED, S.W.S. World Commission on Environment and Development. In Our Common Future; World Commission on Environment and Development: Oslo, Norway, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Galea, C. (Ed.) Introduction. Teaching Business Sustainability: From Theory to Practice; Green Leaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, B.L.; Stavins, R.N.; Vietor, R.H. Environmental Protection and the Social Responsibility of Firms: Perspectives from Law, Economics, and Business; Resources for the Future: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kleindorfer, P.R.; Singhal, K.; Wassenhove, L.N. Sustainable operations management. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2005, 14, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, C.R. Hypothesis testing and evaluation. In Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 200–219. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/239443778_Blackwell_Handbook_of_Judgment_and_Decision_Making (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- RobecoSAM, A.G. Dow Jones Sustainability World Index Guide; Sandp Dow Jones Indices: Zurich, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Danaher, P.J.; Varki, S. Using service quality data for competitive marketing decisions. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2000, 11, 438–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathabadi, H.; Nejad, M.R.O.; Alizadeh, H. An investigation of the factors affecting tourism destination brand equity. Asian J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2017, 6, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Leone, R.P.; Rao, V.R.; Keller, K.L.; Luo, A.M.; McAlister, L.; Srivastava, R. Linking brand equity to customer equity. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 9, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.D.; Sengupta, S. Stakeholder relationships, brand equity, firm performance: A resource-based perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5561–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C.; Christodoulides, G.; de Chernatony, L. A taxonomy of measures for consumer-based brand equity: Drawing on the views of managers in Europe. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2013, 22, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davcik, N.S.; Vinhas da Silva, R.; Hair, J.F. Towards a unified theory of brand equity: Conceptualizations, taxonomy and avenues for future research. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Lehmann, D.R.; Neslin, S.A. Revenue premium as an outcome measure of brand equity. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Biel, A.L. Brand Equity and Advertising: Advertising’s Role in Building Strong Brands; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, G.W.; Johnston, M.W. Marketing Management, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- OECD; Eurostat. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data; OECD: Paris, France, 2005; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264013100-en.pdf?expires=1586229262&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=4E90B7ADB5EA189BB4A044ADC160FFB0 (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Agarwal, S.; Erramilli, M.K.; Dev, C.S. Market orientation and performance in service firms: Role of innovation. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market orientation and the learning organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camisón, C.; Villar-López, A. Non-technical innovation: Organizational memory and learning capabilities as antecedent factors with effects on sustained competitive advantage. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; FreePress: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Javanmard, H.; Hasani, H. The Impact of Market Orientation Indices, Marketing Innovation, and Competitive Advantages on the Business Performance in Distributer Enterprises. Int. J. Ind. Distrib. Bus. 2017, 8, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolba, A.H.; Hassan, S.S. Linking customer-based brand equity with brand market performance: A managerial approach. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2009, 18, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamma, H.M.; Hassan, S.S. Customer and non-customer perspectives for examining corporate reputation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2009, 18, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.H.M.; Chen, P.H.; Yu, T.H.K.; Hsiao, C.Y. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand equity and firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2232–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maine, E.; Lubik, S.; Garnsey, E. Process-based vs. product-based innovation: Value creation by nanotech ventures. Technovation 2012, 32, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geldes, C.; Felzensztein, C. Marketing innovations in the agribusiness sector. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. De Adm. 2013, 26, 108–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesa, M.; Heijs, J.; Baumert, T. The determinants of regional innovation in Europe: A combined factorial and regression knowledge production function approach. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, P. Effects of “best practices” of environmental management on cost advantage: The role of complementary assets. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 663–680. [Google Scholar]

- Acar, A.Z.; Acar, P. The effects of organizational culture and innovativeness on business performance in healthcare industry. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbusch, N.; Brinckmann, J.; Bausch, A. Is innovation always beneficial? A meta-analysis of the relationship between innovation and performance in SMEs. J. Bus. Ventur. 2011, 26, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, V. Firm survival through a crisis: The influence of market orientation, marketing innovation and business strategy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2010, 39, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Dirección de Marketing; Pearson Educación: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.; Hesterly, W. Strategic Management and Competitive Advantage: Concepts and Cases, 4th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D. Aaker on Branding: 20 Principles that Drive Success; Morgan James Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, H. How do innovation culture, marketing innovation and product innovation affect the market performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Technol. Soc. 2017, 51, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The effect of a market orientation on business profitability. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Malhotra, N.K.; Czinkota, M.; Foroudi, P. Marketing innovation: A consequence of competitiveness. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5671–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S. The Impact of Competitive Advantage on Organizational Performance. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleka, A.; Morgan, N.A. Which Competitive Advantage(s)? Competitive Advantage–Market Performance Relationships in International Markets. J. Int. Mark. 2017, 25, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, K.A.; Owusu, O.O. Mobile number portability: On the switching trends among subscribers within the telecommunication industry in a Ghanaian city. Commun. Iima 2013, 13, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook; SAGE Publications Limited: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley and Sons: Hague, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students; Financial Times/Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lavrakas, P.J. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, E.; Kim, E.Y.; Lee, E.K. Modeling consumer adoption of mobile shopping for fashion products in Korea. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A.; Bell, E. Business Research Methods; Bell & Bain Ltd.: Glasgow, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zarmpou, T.; Saprikis, V.; Markos, A.; Vlachopoulou, M. Modeling users’ acceptance of mobile services. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 12, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students. 1996; Pitman: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tharenou, P.; Donohue, R.; Cooper, B. Management Research Methods; Cambridge University Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Akbayrak, B. A comparıson of two data collectıng methods: Interview and questıonnaıres. Hacet. Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Derg. 2000, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.C. Exploring factors affecting the adoption of mobile commerce in Singapore. Telemat. Inform. 2005, 22, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, N.; Carlson, J.; Rosenberger, P.J., III. Factors affecting group-oriented travel intention to major events. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D.M.; Gibson, A.M. Methodology in business ethics research: A review and critical assessment. J. Bus. Ethics 1990, 9, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagnoli, E.; Velicer, W.F. Relation to sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. SEM: An introduction. In Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 629–686. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin, T.R. A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Research Methods in the Study of Leadership; Bell & Bain Ltd.: Glasgow, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Comrey, A.; Lee, H. A First Course in Factor Analysis; Lawrence Eribaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, J.S. “How big is big enough?”: Sample size and goodness of fit in structural equation models with latent variables. Child Dev. 1987, 58, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Some methods for respecifying measurement models to obtain unidimensional construct measurement. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling: A Very Readable Introduction to the Subject, with Good Coverage of Assumptions and SEM’s Relation to Underlying Regression, Factor, and other Techniques; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zait, A.; Bertea, P.E. Financial literacy–Conceptual definition and proposed approach for a measurement instrument. J. Account. Manag. 2015, 4, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.; Naumann, E. Customer satisfaction and business performance: A firm-level analysis. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ambler, T. Marketing and the Bottom Line: The Marketing Metrics to Pump up Cash Flow; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Is the resource-based ‘view’ a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, M.A.; Harrison, J.S. (Eds.) The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Brand Equity | 4 | 0.762 |

| Marketing Innovation | 4 | 0.788 |

| Sustainable Competitive Advantage | 6 | 0.756 |

| Market Performance | 4 | 0.789 |

| Variables | Estimates | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BE_9 | ← | BE | 0.585 | 0.000 |

| BE_10 | ← | BE | 0.698 | 0.000 |

| BE_11 | ← | BE | 0.707 | 0.000 |

| BE_12 | ← | BE | 0.678 | 0.000 |

| MI_13 | ← | MI | 0.725 | 0.000 |

| MI_14 | ← | MI | 0.729 | 0.000 |

| MI_15 | ← | MI | 0.695 | 0.000 |

| MI_16 | ← | MI | 0.719 | 0.000 |

| SCA_21 | ← | SCA | 0.409 | 0.000 |

| SCA_22 | ← | SCA | 0.573 | 0.000 |

| SCA_23 | ← | SCA | 0.676 | 0.000 |

| SCA_24 | ← | SCA | 0.662 | 0.000 |

| SCA_25 | ← | SCA | 0.652 | 0.000 |

| SCA_26 | ← | SCA | 0.667 | 0.000 |

| MP_33 | ← | MP | 0.573 | 0.000 |

| MP_34 | ← | MP | 0.655 | 0.000 |

| MP_35 | ← | MP | 0.812 | 0.000 |

| MP_36 | ← | MP | 0.750 | 0.000 |

| Fit Indices | Recommended Values | Results |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | < 3 | 2.127 |

| GFI (goodness of fit index) | > 0.9 | 0.924 |

| AGFI (adjusted goodness fit ofindex) | > 0.80 | 0.895 |

| RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation) | < 0.08 | 0.067 |

| RMR (root mean square residual) | < 0.08 | 0.039 |

| NFI (normed fit index) | > 0.90 | 0.881 |

| CFI (comparative fit index) | > 0.80 | 0.932 |

| PCLOSE >0.05 0.278 | > 0.05 | 0.132 |

| Path of Variables | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCA | ← | BE | 0.470 | 0.050 | 10.057 | 0.000 |

| SCA | ← | MI | –665 | 0–040 | 16–898 | 0–000 |

| MP | ← | BE | 0.341 | 0.044 | 6.834 | 0.000 |

| MP | ← | MI | 0–636 | 0–034 | 15–536 | 0–000 |

| MP | ← | SCA | 0–559 | 0–040 | 11–623 | 0–000 |

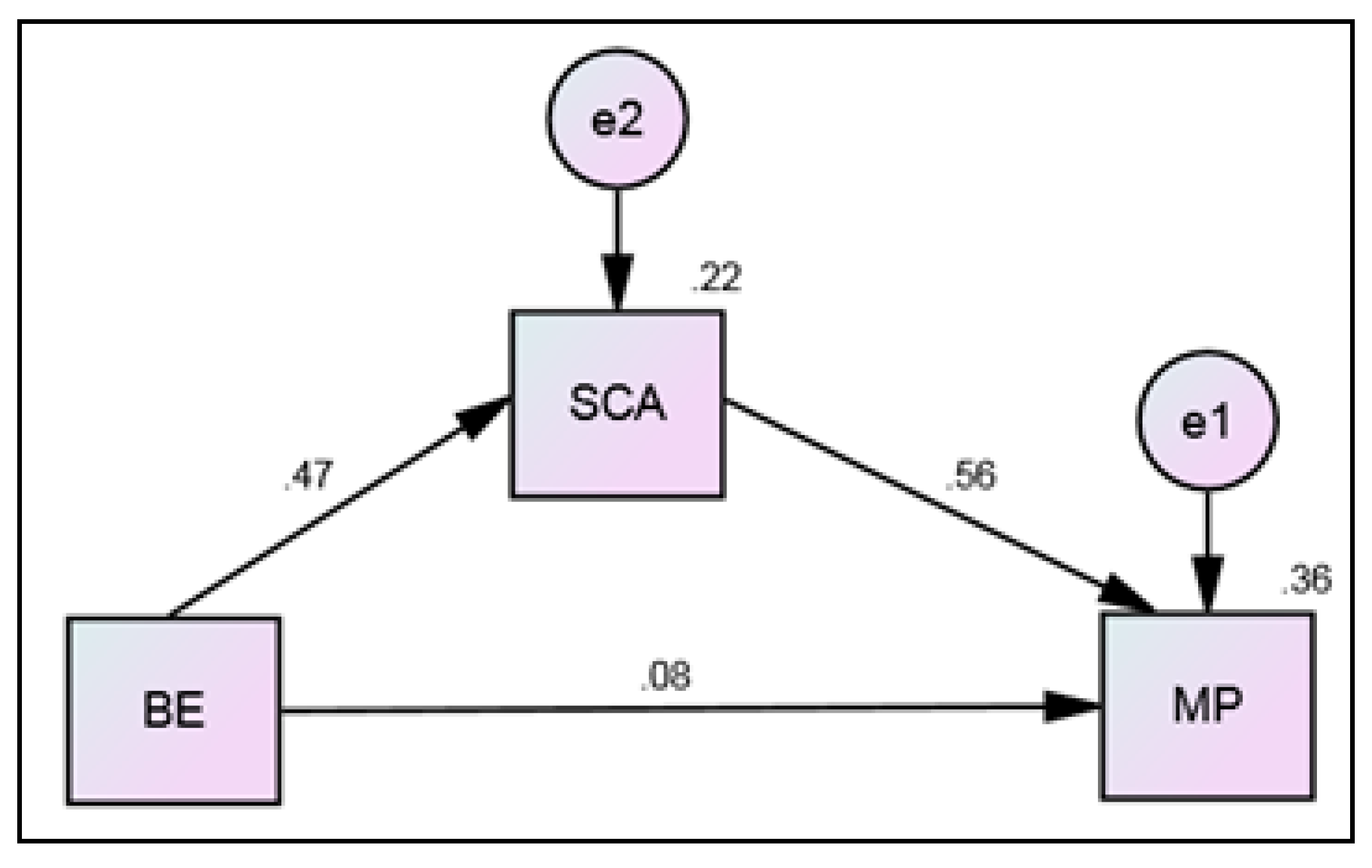

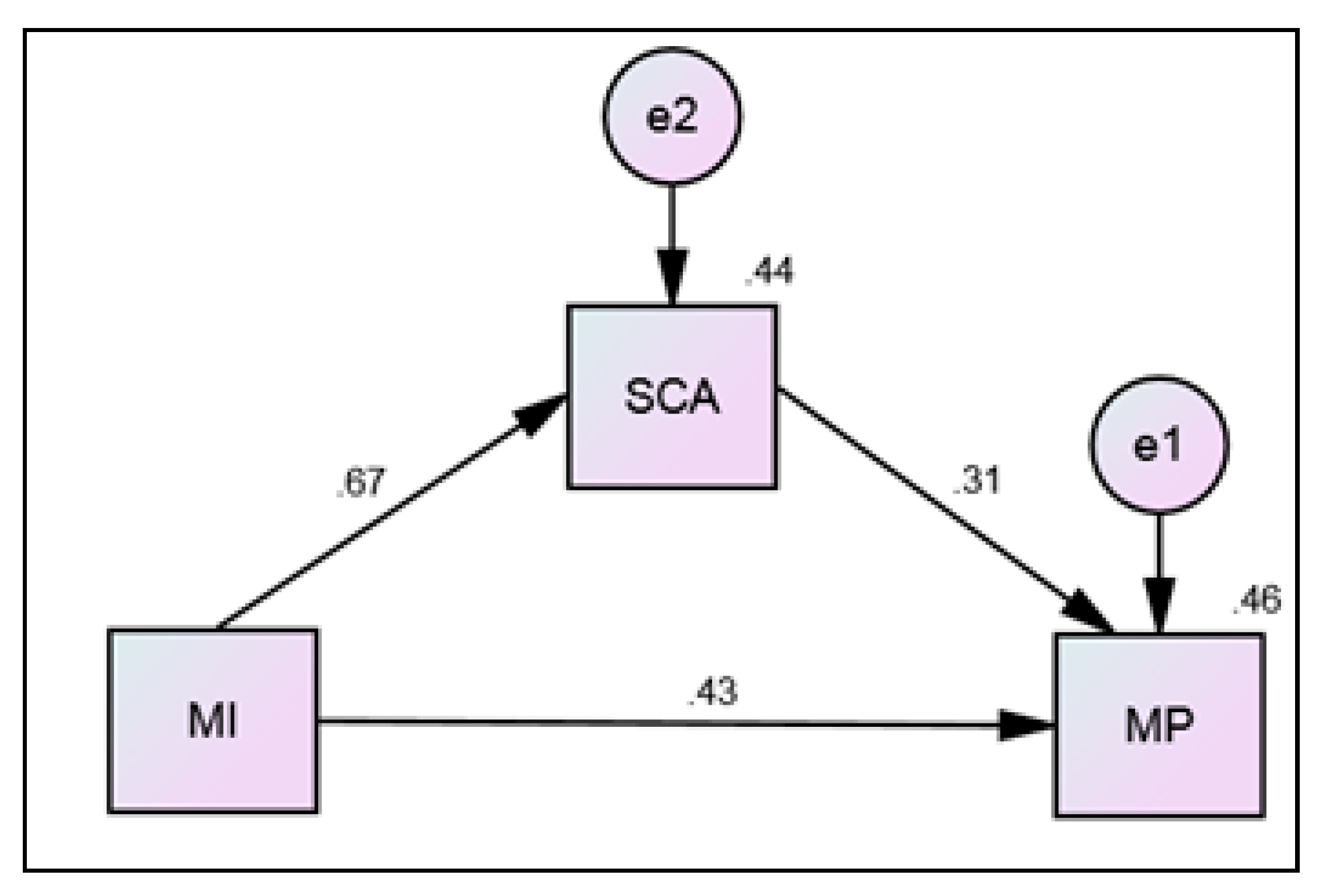

| Hypothesis | Direct Beta w/o Med | Direct Beta w/Med | Indirect Beta | Mediation Type Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 BE–SCA -MP | βa = 0.341, p = 0.000 | βb = 0.078, p = 0.132 | βc = 0.263, p = 0.001 | Full mediation |

| 2 MI–SCA - MP | βa = 0.636, p = 0.000 | βb = 0.430, p = 0.001 | βc = 0.206, p = 0.001 | partial mediation |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hussain, I.; Mu, S.; Mohiuddin, M.; Danish, R.Q.; Sair, S.A. Effects of Sustainable Brand Equity and Marketing Innovation on Market Performance in Hospitality Industry: Mediating Effects of Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072939

Hussain I, Mu S, Mohiuddin M, Danish RQ, Sair SA. Effects of Sustainable Brand Equity and Marketing Innovation on Market Performance in Hospitality Industry: Mediating Effects of Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Sustainability. 2020; 12(7):2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072939

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussain, Ijaz, Shaohong Mu, Muhammad Mohiuddin, Rizwan Qaiser Danish, and Shrafat Ali Sair. 2020. "Effects of Sustainable Brand Equity and Marketing Innovation on Market Performance in Hospitality Industry: Mediating Effects of Sustainable Competitive Advantage" Sustainability 12, no. 7: 2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072939

APA StyleHussain, I., Mu, S., Mohiuddin, M., Danish, R. Q., & Sair, S. A. (2020). Effects of Sustainable Brand Equity and Marketing Innovation on Market Performance in Hospitality Industry: Mediating Effects of Sustainable Competitive Advantage. Sustainability, 12(7), 2939. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072939