The Mechanisms of Mating in Pathogenic Fungi—A Plastic Trait

Abstract

:1. Introduction

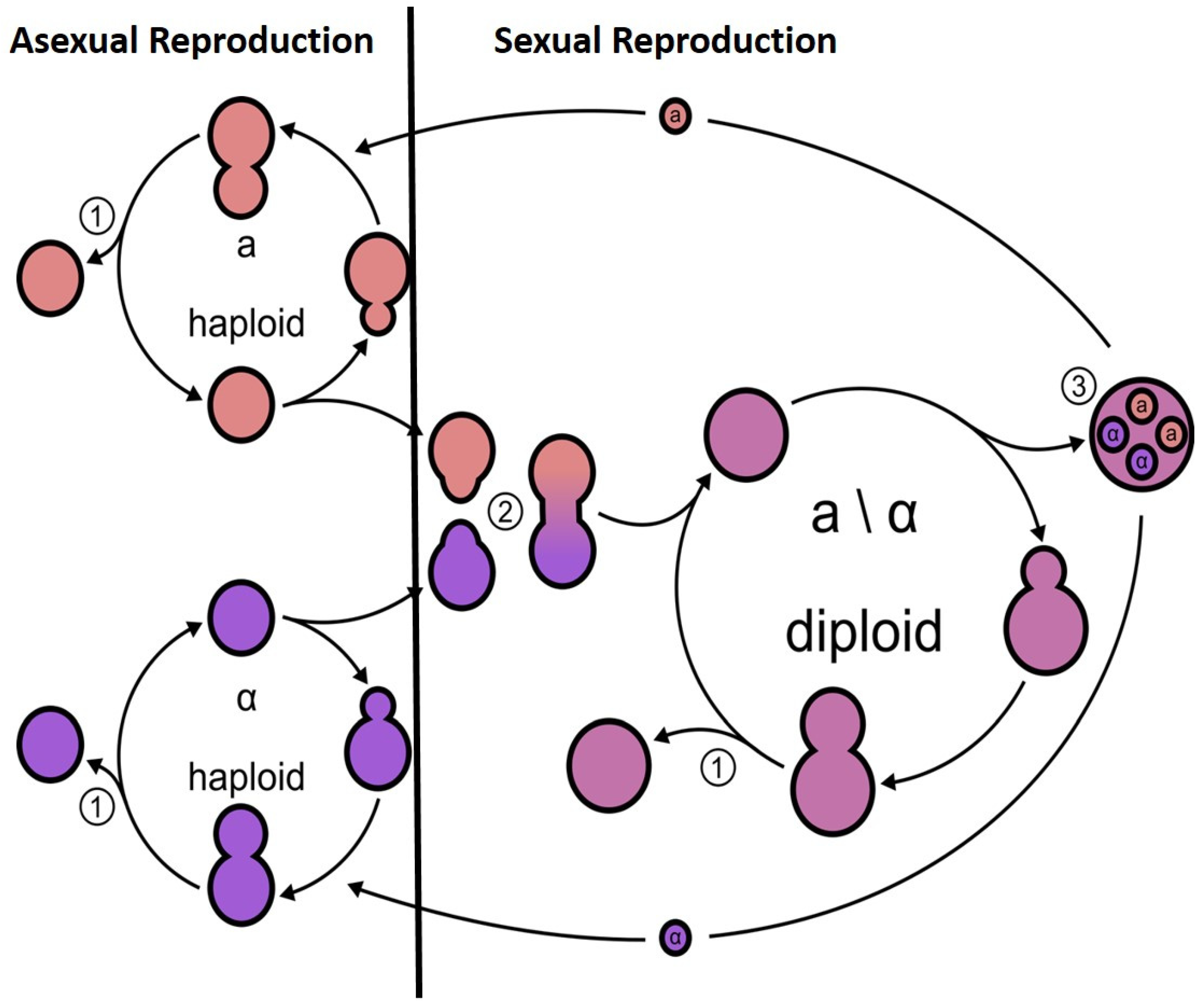

2. Meiosis in the Model Yeast S. cerevisiae

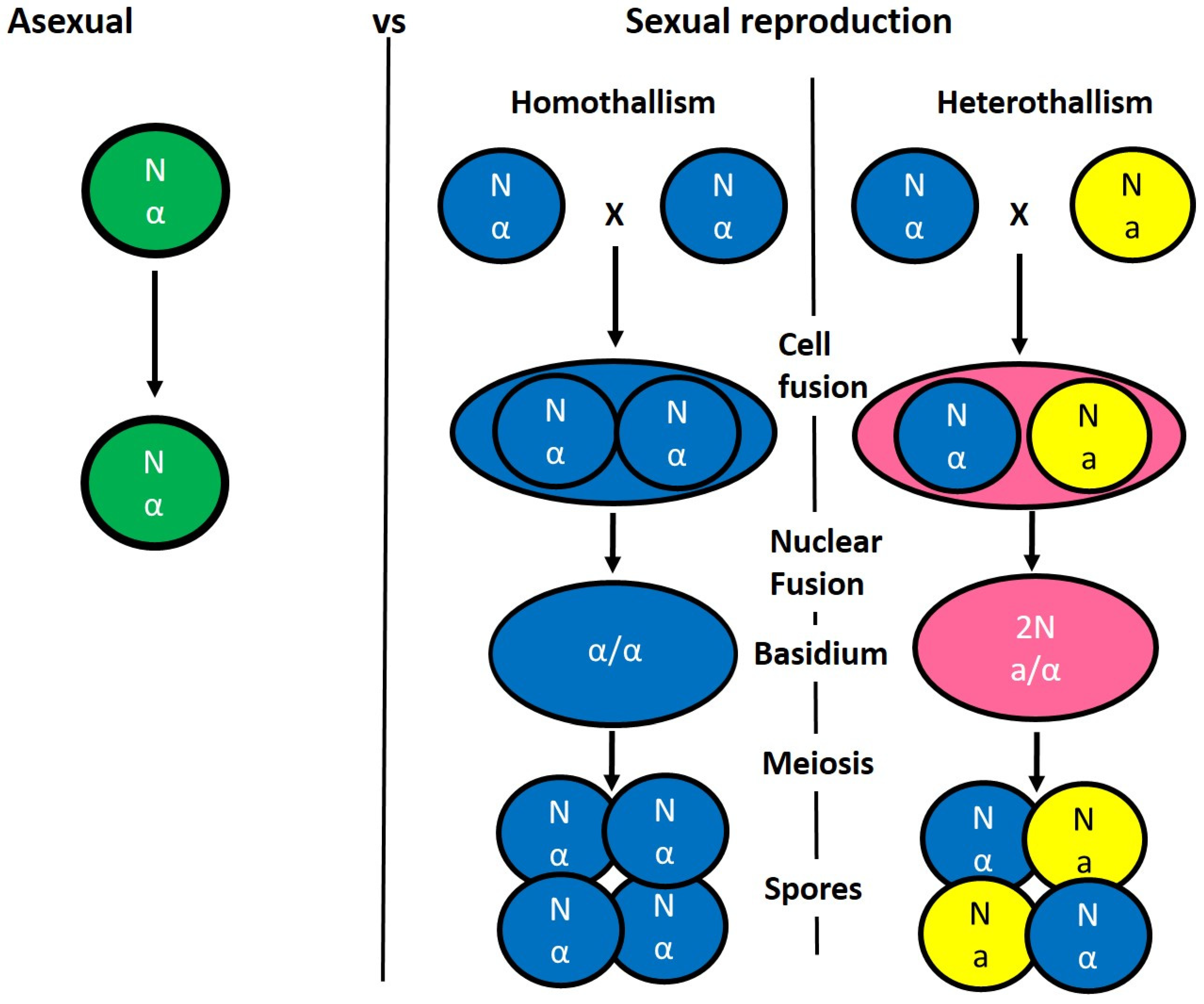

3. Benefit of Sexual vs. Asexual Reproduction

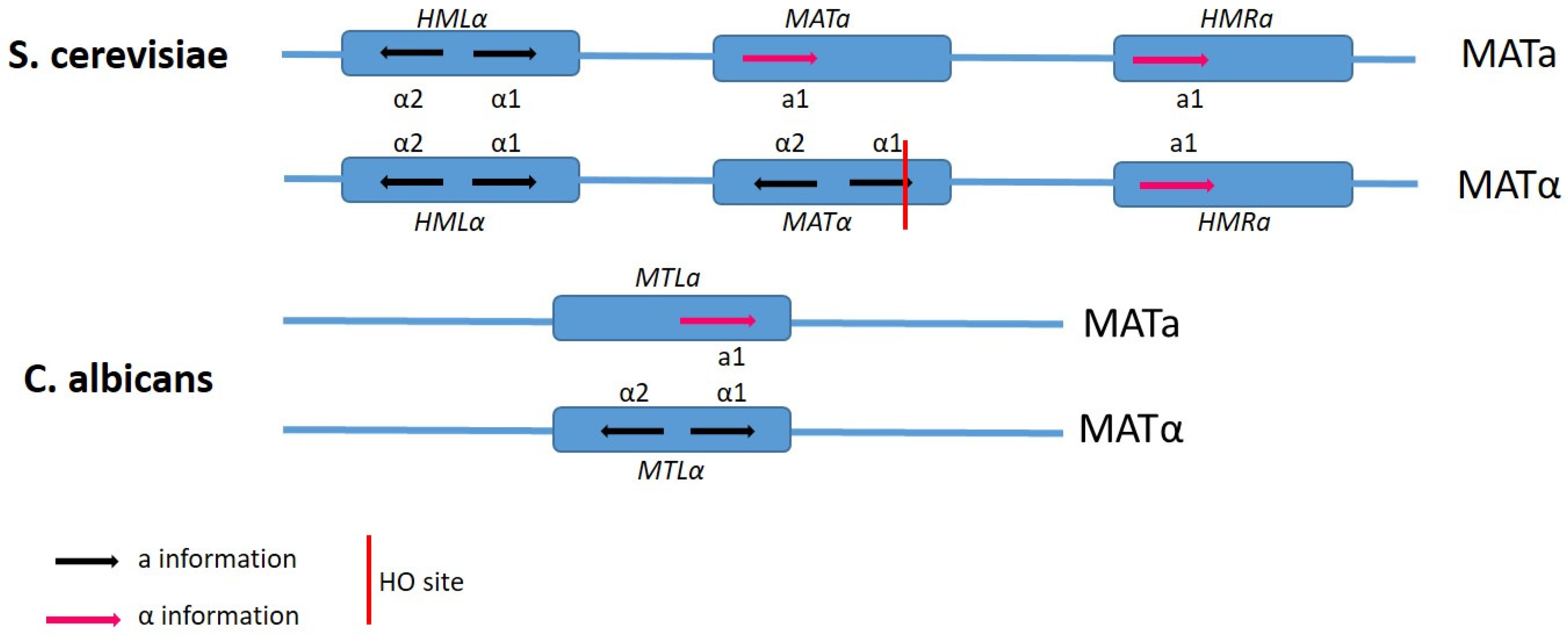

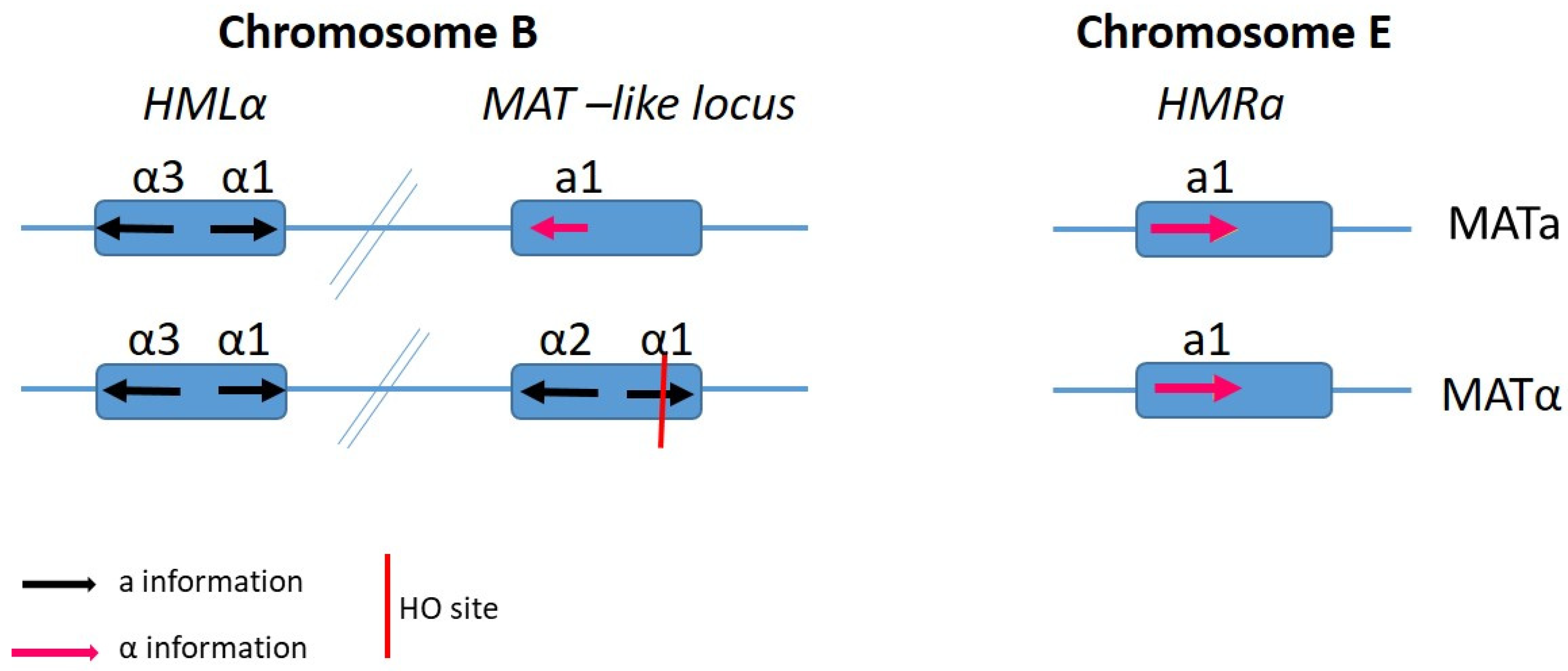

4. Mating Type-Loci and Mate Recognition

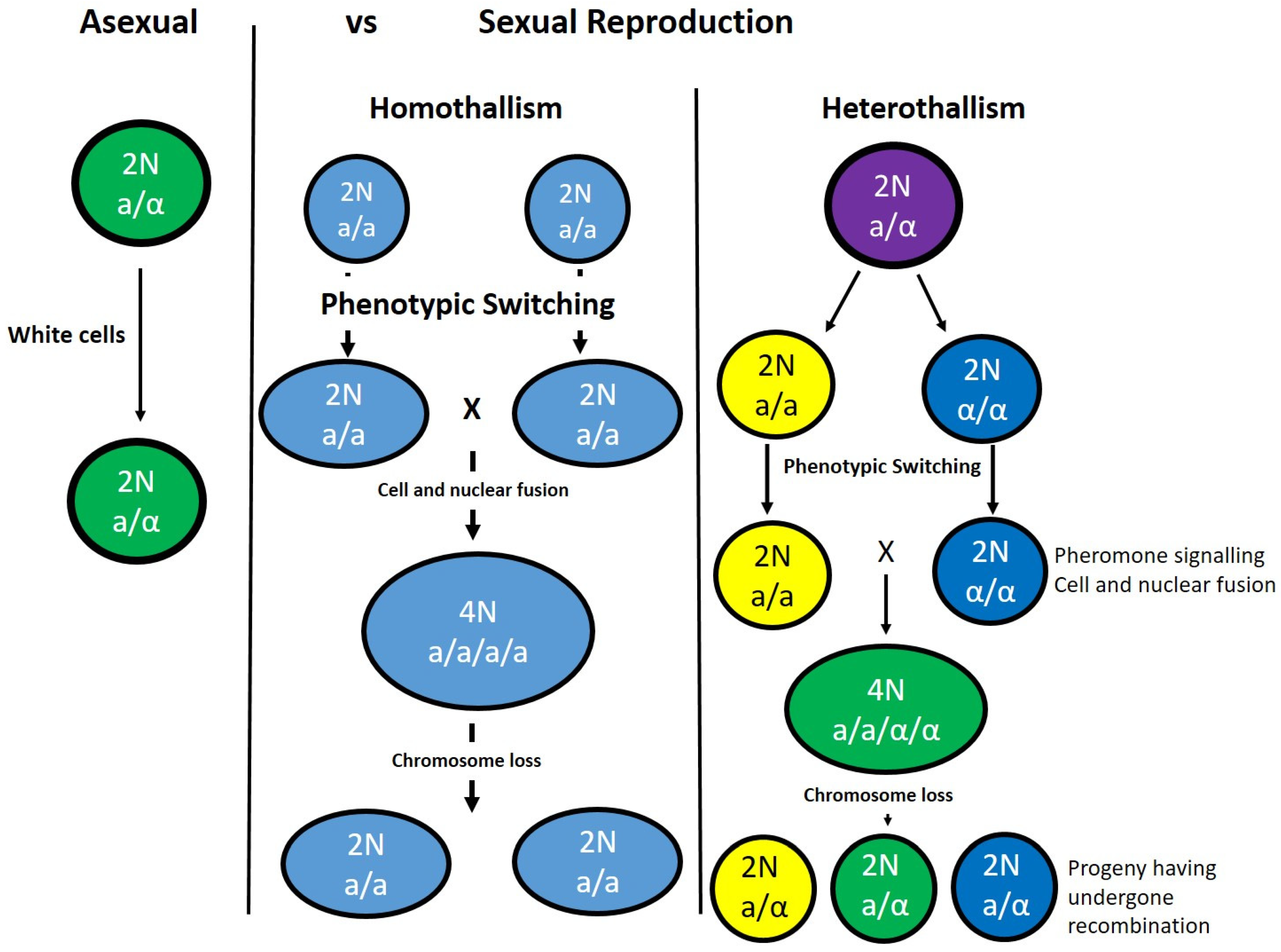

5. Pathogenic Fungi

6. Candida albicans

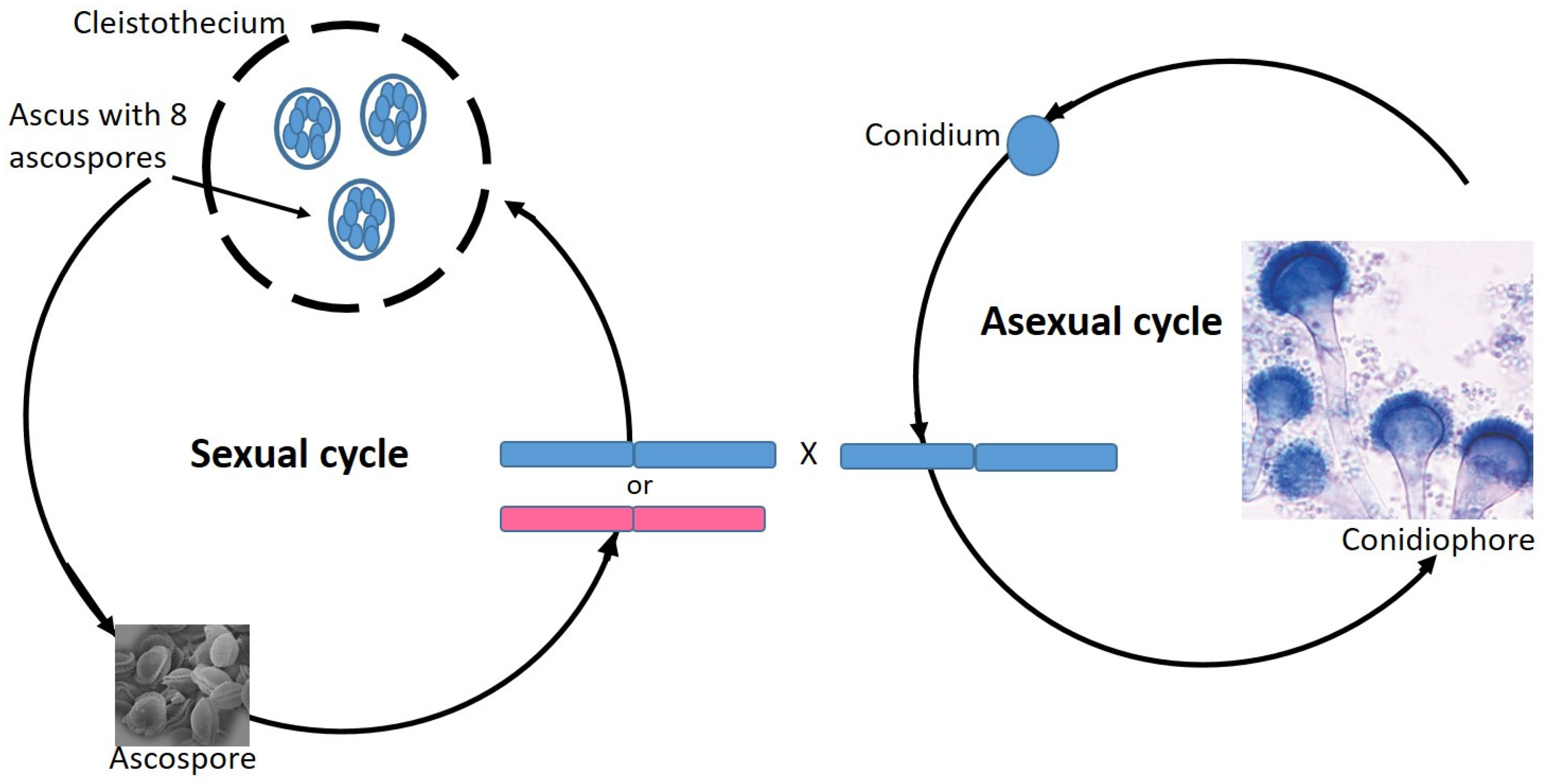

7. Aspergillus Fumigatus

8. Cryptococcus Neoformans

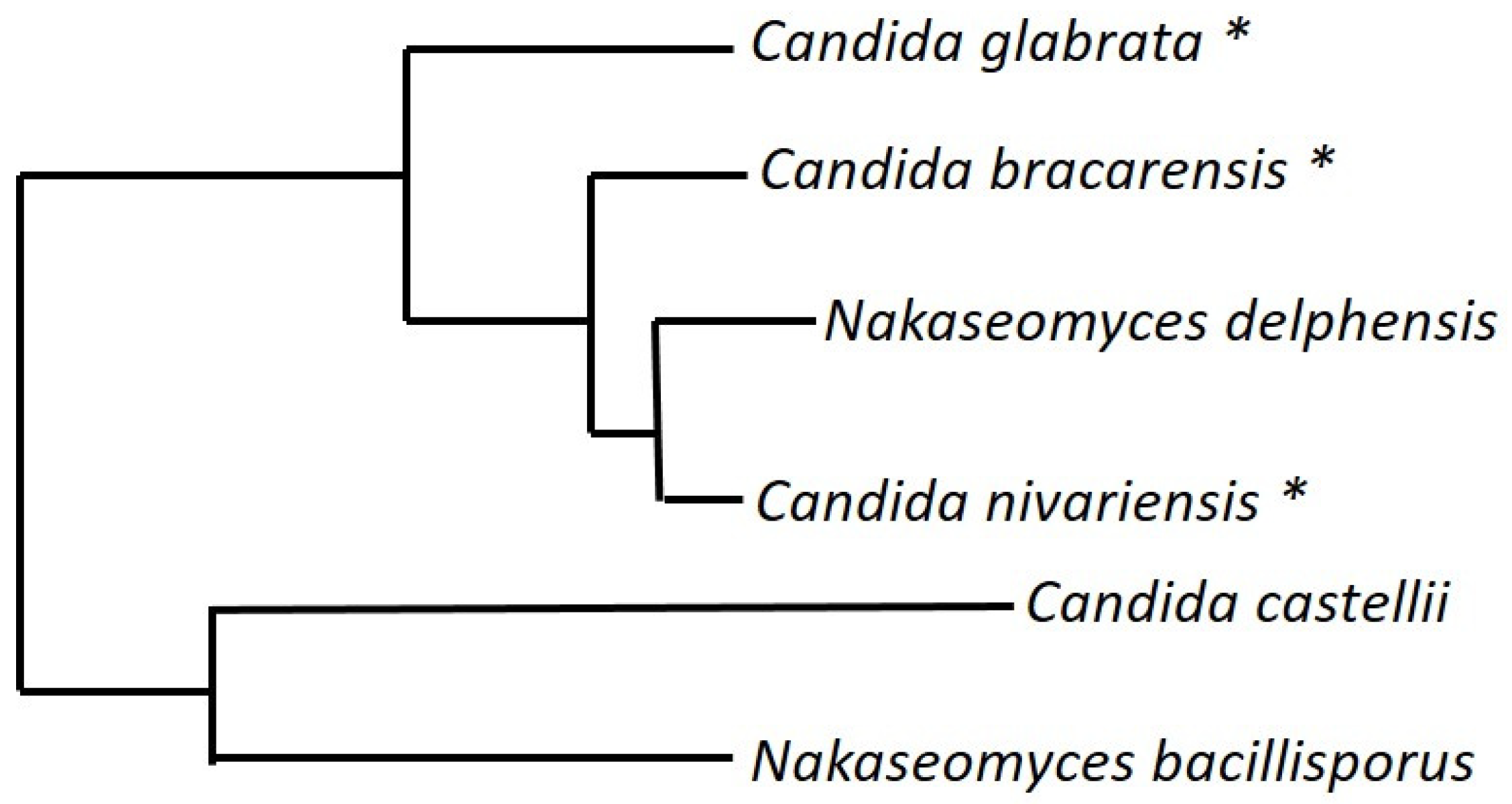

9. The Nakaseomyces Genus

10. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Pauw, B.E. What are fungal infections? Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2011, 3, e2011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlin, D.S.; Rogers, P.D.; Howard, S.J.; Cowen, L.E.; Sanglard, D. Mechanisms of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 5, a019752. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G.D.; Denning, D.W.; Gow, N.A.R.; Levitz, S.M.; Netea, M.G.; White, T.C. Hidden Killers. Hum. Fungal Infect. 2012, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Heitman, J. Microbial Pathogens in the Fungal Kingdom. NIH Public Access. 2012, 25, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuis, B.P.S.; James, T.Y. The frequency of sex in fungi. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Butler, G.; Rasmussen, M.D.; Lin, M.F.; Santos, M.A.S.; Sakthikumar, S.; Munro, C.A.; Rheinbay, E.; Grabherr, M.; Forche, A.; Reedy, J.L.; et al. Evolution of pathogenicity and sexual reproduction in eight Candida genomes. Nature 2009, 459, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Feretzaki, M.; Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Heitman, J. Sex in Fungi. Annu Rev Genet. 2011, 45, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G. Fungal sex and pathogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 23, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Fares, M.A.; Zimmermann, W.; Butler, G.; Wolfe, K.H. Evidence from comparative genomics for a complete sexual cycle in the “asexual” pathogenic yeast Candida glabrata. Genome. Biol. 2003, 4, R10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiard, S.; López-Villavicencio, M.; Hood, M.E.; Giraud, T. Sex, outcrossing and mating types: Unsolved questions in fungi and beyond. J. Evol. Biol. 2012, 25, 1020–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiard, S.; López-Villavicencio, M.; Devier, B.; Hood, M.E.; Fairhead, C.; Giraud, T. Having sex, yes, but with whom? Inferences from fungi on the evolution of anisogamy and mating types. Biol. Rev. 2011, 86, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gorman, C.M.; Fuller, H.T.; Dyer, P.S. Discovery of a sexual cycle in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 2009, 457, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Heitman, J. Is sex necessary? BMC Biol. 2011, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Sun, S.; Billmyre, R.B.; Roach, K.C.; Heitman, J. Unisexual versus bisexual mating in Cryptococcus neoformans: Consequences and biological impacts. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 78, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halliday, C.L.; Carter, D.A. Clonal reproduction and limited dispersal in an environmental population of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii isolates from Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaldón, T.; Martin, T.; Marcet-Houben, M.; Durrens, P.; Bolotin-Fukuhara, M.; Lespinet, O.; Arnaise, S.; Boisnard, S.; Aguileta, G.; Atanasova, R.; et al. Comparative genomics of emerging pathogens in the Candida glabrata clade. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaldón, T.; Fairhead, C. Genomes shed light on the secret life of Candida glarbrata, not so asexual, not so commensal. Current genetics. 2019, 65, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Enache-Angoulvant, A.; Guitard, J.; Grenouillet, F.; Martin, T.; Durrens, P.; Fairhead, C.; Hennequin, C. Rapid discrimination between Candida glabrata, Candida nivariensis, and Candida bracarensis by use of a singleplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 3375–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.M.; Sokolsky, T.; Tucker, C.M.; Chan, L.Y.; Boselli, M.; Dunham, M.J.; Amon, A.; Yona, A.H.; Manor, Y.S.; Herbst, R.H.; et al. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata clinical isolates exhibiting reduced echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 8, 2892–2894. [Google Scholar]

- Vershon, A.K.; Pierce, M. Transcriptional regulation of meiosis in yeast. Curr opinion in cell boil. 2000, 12, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassir, Y.; Granot, D.; Simchen, G. IME7, a Positive Regulator in S cerevisiae Gene of Meiosis. Cell 1988, 52, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strudwick, N.; Brown, M.; Parmar, V.M.; Schröder, M. Ime1 and Ime2 are required for pseudohyphal growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on nonfermentable carbon sources. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010, 30, 5514–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnone, J.T.; Robbins-Pianka, A.; Arace, J.R.; Kass-Gergi, S.; McAlear, M. The adjacent positioning of co-regulated gene pairs is widely conserved across eukaryotes. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magadum, S.; Banerjee, U.; Murugan, P.; Gangapur, D.; Ravikesavan, R. Gene duplication as a major force in evolution. J. Genet. 2013, 92, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forche, A.; Alby, K.; Schaefer, D.; Johnson, A.D.; Berman, J.; Bennett, R.J. The parasexual cycle in Candida albicans provides an alternative pathway to meiosis for the formation of recombinant strains. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, H.; Hennequin, C.; Gallaud, J.; Dujon, B.; Fairhead, C. The asexual yeast Candida glabrata maintains distinct a and α haploid mating types. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irniger, S. The Ime2 protein kinase family in fungi: More duties than just meiosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 80, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herskowitz, I. Life cycle of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Rev. 1988, 52, 536–553. [Google Scholar]

- Astell, C.R.; Ahlstrom-Jonasson, L.; Smith, M.; Tatchell, K.; Nasmyth, K.A.; Hall, B.D. The sequence of the DNAs coding for the mating-type loci of saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell 1981, 27, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, D.C.; Bruhn, L.; Westby, C.A.; Sprague, G.F. Transcription of alpha-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: DNA sequence requirements for activity of the coregulator alpha 1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1993, 13, 6866–6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehr, J.; Heaney, M.; Sapiro, V.; Lo, S. Letters To Nature. Nature 2002, 415, 633–637. [Google Scholar]

- Galgoczy, D.J.; Cassidy-Stone, A.; Llinas, M.; O’Rourke, S.M.; Herskowitz, I.; DeRisi, J.L.; Johnson, A.D. Genomic dissection of the cell-type-specification circuit in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 18069–18074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowdish, K.S.; Yuan, H.E.; Mitchell, A.P. Positive control of yeast meiotic genes by the negative regulator UME6. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 15, 2955–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.E.; Driscoll, S.E.; Sia, R.A.L.; Yuan, H.E.; Mitchell, A.P. Genetic evidence for transcriptional activation by the yeast IME1 gene product. Genetics 1993, 133, 775–784. [Google Scholar]

- Honigberg, S.M.; Purnapatre, K. Signal pathway integration in the switch from the mitotic cell cycle to meiosis in yeast. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshida, M.; Kawaguchi, H.; Sakata, Y.; Kominami, K.I.; Hirano, M.; Shima, H.; Akada, R.; Yamashita, I. Initiation of meiosis and sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires a novel protein kinase homologue. MGG Mol. Gen. Genet. 1990, 221, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.C.; Clancy, M.J. IME4, a gene that mediates MAT and nutritional control of meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992, 12, 1078–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttmann-Raviv, N.; Martin, S.; Kassir, Y. Ime2, a meiosis-specific kinase in yeast, is required for destabilization of its transcriptional activator, Ime1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 2047–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Nurse, P. Cohesin Rec8 is required for reductional chromosome segregation at meiosis. Nature 1999, 400, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, G.F.; Kerrest, A.; Lafontaine, I.; Dujon, B. Comparative genomics of hemiascomycete yeasts: Genes involved in DNA replication, repair, and recombination. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 1011–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Du, H.; Guan, G.; Dai, Y.; Nobile, C.J.; Liang, W.; Cao, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhong, J.; Huang, G. Discovery of a “White-Gray-Opaque” Tristable Phenotypic Switching System in Candida albicans: Roles of Non-genetic Diversity in Host Adaptation. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, G.; Kenny, C.; Fagan, A.; Kurischko, C.; Gaillardin, C.; Wolfe, K.H. Evolution of the MAT locus and its Ho endonuclease in yeast species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoletti, M.; Rydholm, C.; Schwier, E.U.; Anderson, M.J.; Szakacs, G.; Lutzoni, F.; Debeaupuis, J.P.; Latgé, J.P.; Denning, D.W.; Dyer, P.S. Evidence for sexuality in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCallum, D.M.; Findon, H.; Kenny, C.C.; Butler, G.; Haynes, K.; Odds, F.C. Different consequences of ACE2 and SWI5 gene disruptions for virulence of pathogenic and nonpathogenic yeasts. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 5244–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcagno, A.M.; Bignell, E.; Warn, P.; Jones, M.D.; Denning, D.W.; Mühlschlegel, F.A.; Rogers, T.R.; Haynes, K. Candida glabrata STE12 is required for wild-type levels of virulence and nitrogen starvation induced filamentation. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 50, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagno, A.M.; Bignell, E.; Rogers, T.R.; Canedo, M.; Mühlschleger, F.A.; Haynes, K. Candida glabrata Ste20 is involved in maintaining cell wall integrity and adaptation to hypertonic stress and is required for wild-type levels of virulence. Yeast 2004, 21, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitman, J. Evolution of eukaryotic microbial pathogens via covert sexual reproduction. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borneman, A.R.; Gianoulis, T.A.; Zhang, Z.D.; Yu, H.; Rozowsky, J.; Seringhaus, M.R.; Lu, Y.W.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. Divergence of transcription factor binding sites across related yeast species. Science 2007, 317, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada, L.; Sugui, J.A.; Eckhaus, M.A.; Chang, Y.C.; Mounaud, S.; Figat, A.; Joardar, V.; Pakala, S.B.; Pakala, S.; Venepally, P.; et al. Genetic Analysis Using an Isogenic Mating Pair of Aspergillus fumigatus Identifies Azole Resistance Genes and Lack of MAT Locus’s Role in Virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seider, K.; Gerwien, F.; Kasper, L.; Allert, S.; Brunke, S.; Jablonowski, N.; Schwarzmüller, T.; Barz, D.; Rupp, S.; Kuchler, K.; et al. Immune evasion, stress resistance, and efficient nutrient acquisition are crucial for intracellular survival of Candida glabrata within macrophages. Eukaryot. Cell 2014, 13, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale-Silva, L.; Ischer, F.; Leibundgut-Landmann, S.; Sanglard, D. Gain-of-function mutations in PDR1, a regulator of antifungal drug resistance in candida glabrata, control adherence to host cells. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 1709–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hörandl, E. A combinational theory for maintenance of sex. Heredity (Edinb). 2010, 103, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.S.; Reese, T.S.; De Camilli, P.; Rizo, J.; Gierasch, L.M.; Anderson, R.G.W.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Zuber, J.F.; Spiess, M.; Rapoport, I.; et al. Identification of a Mating Type–Like Locus in the Asexual Pathogenic Yeast Candida albicans. Science 1999, 285, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, J.A.; Heitman, J. Fungal mating-type loci. Curr. Biol. 2003, 13, R792–R795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson; Wilken; van der Nest; Wingfield; Wingfield It’s All in the Genes: The Regulatory Pathways of Sexual Reproduction in Filamentous Ascomycetes. Genes (Basel). 2019, 10, 330. [CrossRef]

- Ene, I.V.; Bennett, R.J.; Anderson, M.Z. Mechanisms of genome evolution in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 52, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israeli, E. The “obligate diploid” Candida albicans forms mating-competent haploids. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2013, 15, 251. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.J.; Uhl, M.A.; Miller, M.G.; Johnson, A.D. Identification and Characterization of a Candida albicans Mating Pheromone. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 8189–8201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.M.; Raisner, R.M.; Johnson, A.D. Evidence for mating of the “asexual” yeast Candida albicans in a mammalian host. Science 2000, 289, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glittenberg, M.T.; Kounatidis, I.; Christensen, D.; Kostov, M.; Kimber, S.; Roberts, I.; Ligoxygakis, P. Pathogen and host factors are needed to provoke a systemic host response to gastrointestinal infection of Drosophila larvae by Candida albicans. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011, 4, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.G.; Johnson, A.D. White-opaque switching in Candida albicans is controlled by mating-type locus homeodomain proteins and allows efficient mating. Cell 2002, 110, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “White-opaque transition”: A second high-frequency switching system in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 189–197. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Yi, S.; Sahni, N.; Daniels, K.J.; Srikantha, T.; Soll, D.R. N-acetylglucosamine induces white to opaque switching, a mating prerequisite in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, A.J.S. The yeast mating-type switching mechanism: A memoir. Genetics 2010, 186, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montelone, B.A. Yeast Mating Type. ELS. 2003, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Latgé, J.P. Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 310–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janbon, G.; Quintin, J.; Lanternier, F.; d’Enfert, C. Studying fungal pathogens of humans and fungal infections: Fungal diversity and diversity of approaches. Genes Immun. 2019, 20, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengeler, K.B.; Fox, D.S.; Fraser, J.A.; Allen, A.; Forrester, K.; Dietrich, F.S.; Heitman, J. Mating-type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans: A step in the evolution of sex chromosomes. Eukaryot. Cell 2002, 1, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapping of the Cryptococcus neoformans MATα locus: Presence of mating type-specific mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade homologs. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 6222–6227. [CrossRef]

- Wickes, B.L.; Mayorga, M.E.; Edman, U.; Edman, J.C. Dimorphism and haploid fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans: Association with the alpha-mating type. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 7327–7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, L.; Disturbance, P.B.; Design, M.J.E. Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature 2005, 434, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, H.; Thierry, A.; Coppée, J.Y.; Gouyette, C.; Hennequin, C.; Sismeiro, O.; Talla, E.; Dujon, B.; Fairhead, C. Genomic polymorphism in the population of Candida glabrata: Gene copy-number variation and chromosomal translocations. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2009, 46, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, D.W.; Wolfe, K.H.; Butler, G. Genomic differences between Candida glabrata and Saccharomyces cerevisiae around the MRPL28 and GCN3 loci. Yeast 2002, 19, 991–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, D.A.; O’Gaora, P.; Byrne, K.P.; Butler, G. Analysis of gene evolution and metabolic pathways using the Candida Gene Order Browser. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikantha, T.; Lachke, S.A.; Soll, D.R. Three mating type-like loci in Candida glabrata. Eukaryot. Cell 2003, 2, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodgson, A.R.; Pujol, C.; Pfaller, M.A.; Denning, D.W.; Soll, D.R. Evidence for recombination in Candida glabrata. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angoulvant, A.; Guitard, J.; Hennequin, C. Old and new pathogenic Nakaseomyces species: Epidemiology, biology, identification, pathogenicity and antifungal resistance. FEMS Yeast Res. 2016, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| S. cerevisiae Associated Genes | Candida albicans Associated Genes | Candida glabrata Associated Genes | Aspergillus fumigatus Associated Genes | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IME1 | - | CAGL0M09042g | - | Master regulator of meiosis that is active only during meiotic events; activates transcription of early meiotic genes through interaction with Ume6p, degraded by the 26S proteasome following phosphorylation by Ime2p |

| IME2 | orf19.2395 | CAGL0G04455g | Afu2g13140 | Serine/threonine protein kinase involved in activation of meiosis; associates with Ime1p and mediates its stability, activates Ndt80p; IME2 expression is positively regulated by Ime1p |

| IME4 | orf19.1476 | CAGL0A03300g | Afu2g05600 | mRNA N6-adenosine methyltransferase required for entry into meiosis; mediates N6-adenosine methylation of bulk mRNA during the induction of sporulation which includes the meiotic regulators IME1, IME2 and IME4 itself; repressed in haploids via production of antisense IME4 transcripts; transcribed in diploid cells where antisense transcription is repressed |

| KAR1 | - | CAGL0J11418g | - | Protein involved in karyogamy and spindle pole body duplication; involved in karyogamy during mating; involved in spindle pole body duplication during mitosis |

| KAR3 | orf19.564 | CAGL0D04994g | Afu2g14280 | Minus-end-directed microtubule motor; functions in mitosis and meiosis, localizes to the spindle pole body and localization is dependent on functional Cik1p, required for nuclear fusion during mating |

| KAR4 | orf19.3736 | CAGL0B00462g | - | Transcription factor required for response to pheromones; also required during meiosis; exists in two forms, a slower-migrating form more abundant during vegetative growth and a faster-migrating form induced by pheromone |

| MEK1 | orf19.1874 | CAGL0D02244g | Afu5g07950 | Meiosis-specific serine/threonine protein kinase; functions in meiotic checkpoint, promotes recombination between homologous chromosomes by suppressing double strand break repair between sister chromatids; stabilizes Hop1-Thr318 phosphorylation to promote interhomolog recombination and checkpoint responses during meiosis |

| NDT80 | orf19.2119 | CAGL0L13090g | Afu2g09890 | Meiosis-specific transcription factor; required for exit from pachytene and for full meiotic recombination; activates middle sporulation genes |

| RAD50 | orf19.1648 | CAGL0J07788g | Afu4g12680 | Initiation of meiotic DSBs, telomere maintenance, and nonhomologous end joining |

| RAD51 | orf19.3752 | CAGL0I05544g | Afu1g10410 | Strand exchange protein; forms a helical filament with DNA that searches for homology; involved in the recombinational repair of double-strand breaks in DNA during vegetative growth and meiosis |

| RIM11 | orf19.791 | Afu6g05120 | ||

| RME1 | orf19.4438 | CAGL0K04257g | - | Zinc finger protein involved in control of meiosis; prevents meiosis by repressing IME1 expression and promotes mitosis by activating CLN2 expression; directly repressed by a1-alpha2 regulator; mediates cell type control of sporulation |

| SET3 | orf19.7221 | CAGL0L03091g | Afu2g11210 | Defining member of the SET3 histone deacetylase complex; which is a meiosis-specific repressor of sporulation genes; necessary for efficient transcription by RNAPII; one of two yeast proteins that contains both SET and PHD domains |

| SPO11 | orf19.3589 | CAGL0C02783g | Afu5g04070 | Meiosis-specific protein that initiates meiotic recombination; initiates meiotic recombination by catalysing the formation of double-strand breaks in DNA via a transesterification reaction; required for homologous chromosome pairing and synaptonemal complex formation |

| SSP1 | orf19.3173 | CAGL0M13365g | Afu8g03930 | Protein involved in the control of meiotic nuclear division; also involved in the coordination of meiosis with spore formation; transcription is induced midway through meiosis |

| STE2 | orf19.696 | CAGL0K12430g | Afu3g14330 | Receptor for alpha-factor pheromone; seven transmembrane-domain GPCR that interacts with both pheromone and a heterotrimeric G protein to initiate the signalling response that leads to mating between haploid a and alpha cells |

| STE3 | orf19.2492 | CAGL0M08184g | Afu5g07880 | Receptor for a factor pheromone; couples to MAP kinase cascade to mediate pheromone response; transcribed in alpha cells and required for mating by alpha cells |

| STE6 | orf19.7440 | CAGL0K00363g | Afu4g08800 | Plasma membrane ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter; required for the export of a-factor, catalyses ATP hydrolysis coupled to a-factor transport; expressed only in MATa cells |

| STE7 | orf19.469 | CAGL0I03498g | Afu3g05900 | Signal transducing MAP kinase; involved in pheromone response where it phosphorylates Fus3p; involved in the pseudohyphal/invasive growth pathway where it phosphorylates of Kss1p; phosphorylated by Ste11p |

| SUT1 | orf19.4342 | CAGLI04246g | Afu5g06210 | Transcription factor of the Zn(II)2Cys6 family; positively regulates mating with SUT2 by repressing expression of genes which act as mating inhibitors |

| SUT2 | - | CAGL0L09383g | - | Putative transcription factor of the Zn2Cys6 family; positively regulates mating along with SUT1 by repressing the expression of genes (PRR2, NCE102 and RHO5) which function as mating inhibitors |

| UME6 | orf19.1822 | CAGL0F05357g | Afu3g15290 | Key transcriptional regulator of early meiotic genes; involved in chromatin remodelling and transcriptional repression via DNA looping; binds URS1 upstream regulatory sequence, couples metabolic responses to nutritional cues with initiation and progression of meiosis, forms complex with Ime1p |

| S. cerevisiae | C. albicans | C. glabrata | A. fumigatus | C. neoformans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifestyle | Generally regarded as safe | Commensal and pathogenic | Commensal and pathogenic | Pathogenic | Pathogenic |

| Ploidy | Haploid in the majority of cases | Diploid with rare haploid strains observed | Haploid with aneuploidy observed in some clinical isolates | Haploid | Haploid with diploid blastospores able to undergo meiosis. |

| Mating genes | Present | Present | Present | Present | Present |

| Sexual reproduction | Homothallic | Asexual; Parasexual cycle observed | Not observed | Asexual; Rare sexual reproduction observed | Asexual; Rare sexual reproduction observed |

| Morphology | Yeast | Yeast, pseudohyphae and hyphae | Yeast | Conidiospores | Yeast, hyphae and basidiospores |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Usher, J. The Mechanisms of Mating in Pathogenic Fungi—A Plastic Trait. Genes 2019, 10, 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100831

Usher J. The Mechanisms of Mating in Pathogenic Fungi—A Plastic Trait. Genes. 2019; 10(10):831. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100831

Chicago/Turabian StyleUsher, Jane. 2019. "The Mechanisms of Mating in Pathogenic Fungi—A Plastic Trait" Genes 10, no. 10: 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100831

APA StyleUsher, J. (2019). The Mechanisms of Mating in Pathogenic Fungi—A Plastic Trait. Genes, 10(10), 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100831