Reproductive Investment Across Native and Invasive Regions in Pittosporum undulatum Vent., a Range Expanding Gynodioecious Tree

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Species: Pittosporum undulatum Vent. (Sweet Pittosporum)

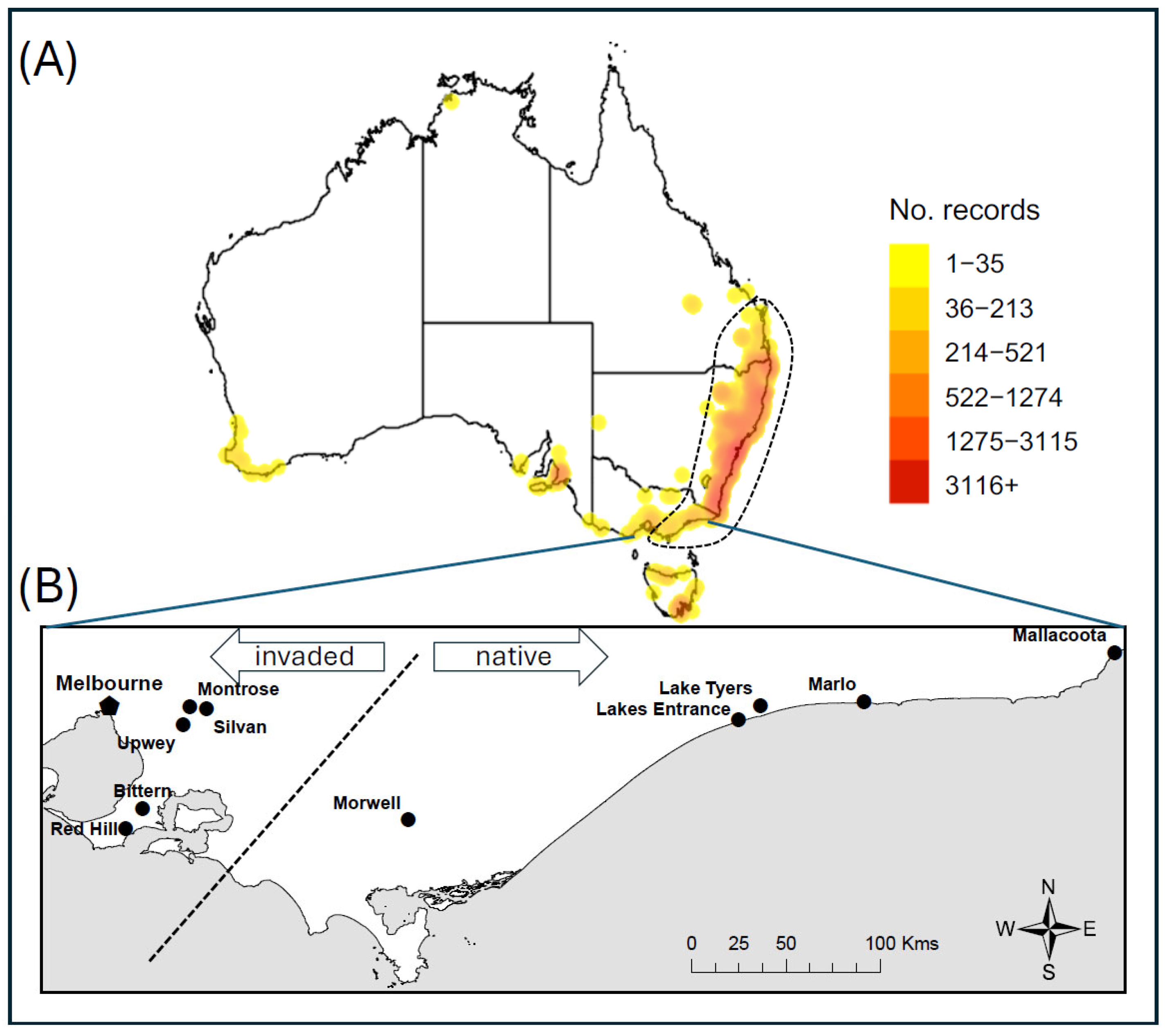

2.2. Site Description

2.3. Sex Determination and Resource Analysis

2.4. Fruit Load and Seed Mass Determination

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

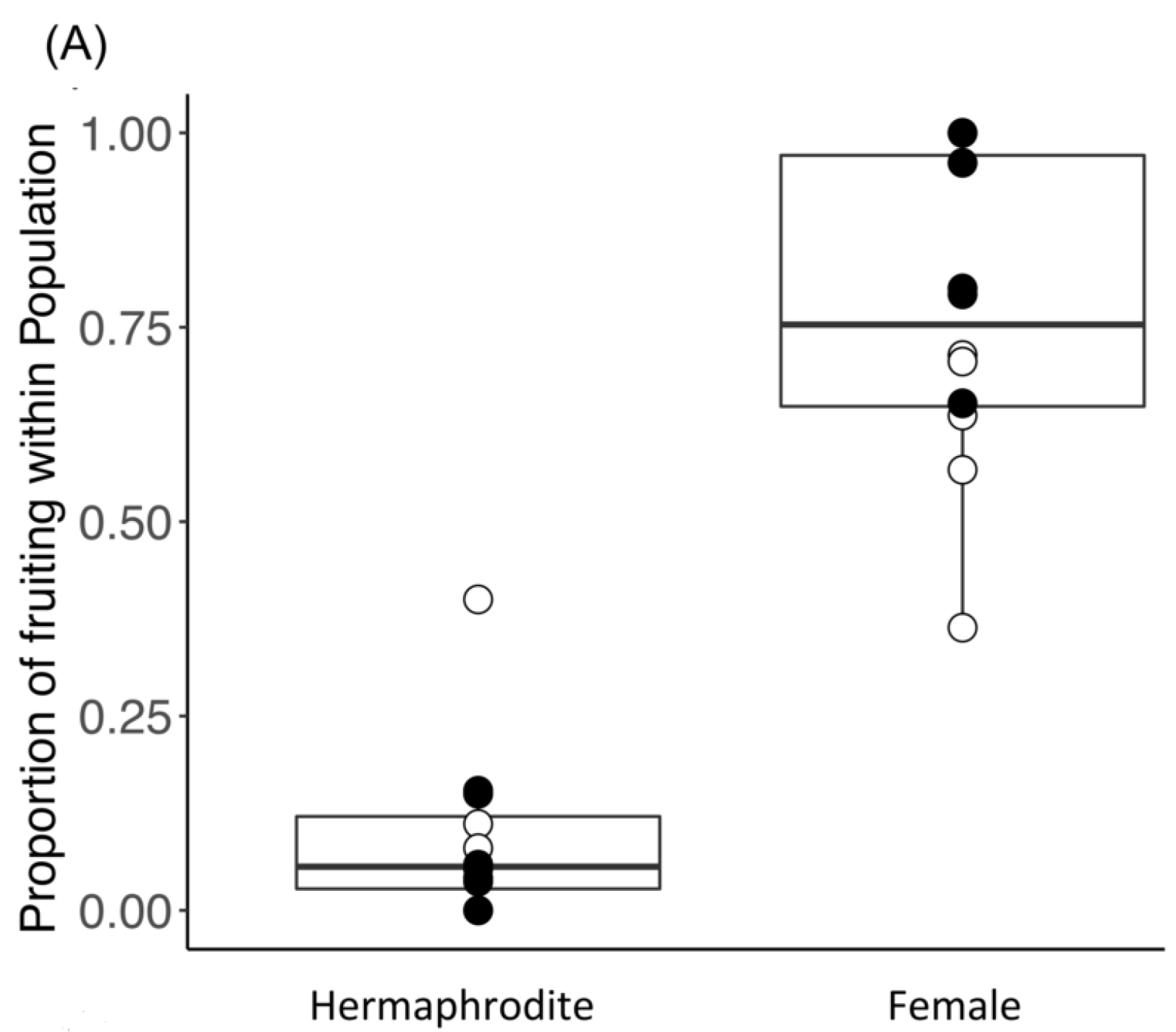

3.1. Reproductive Traits

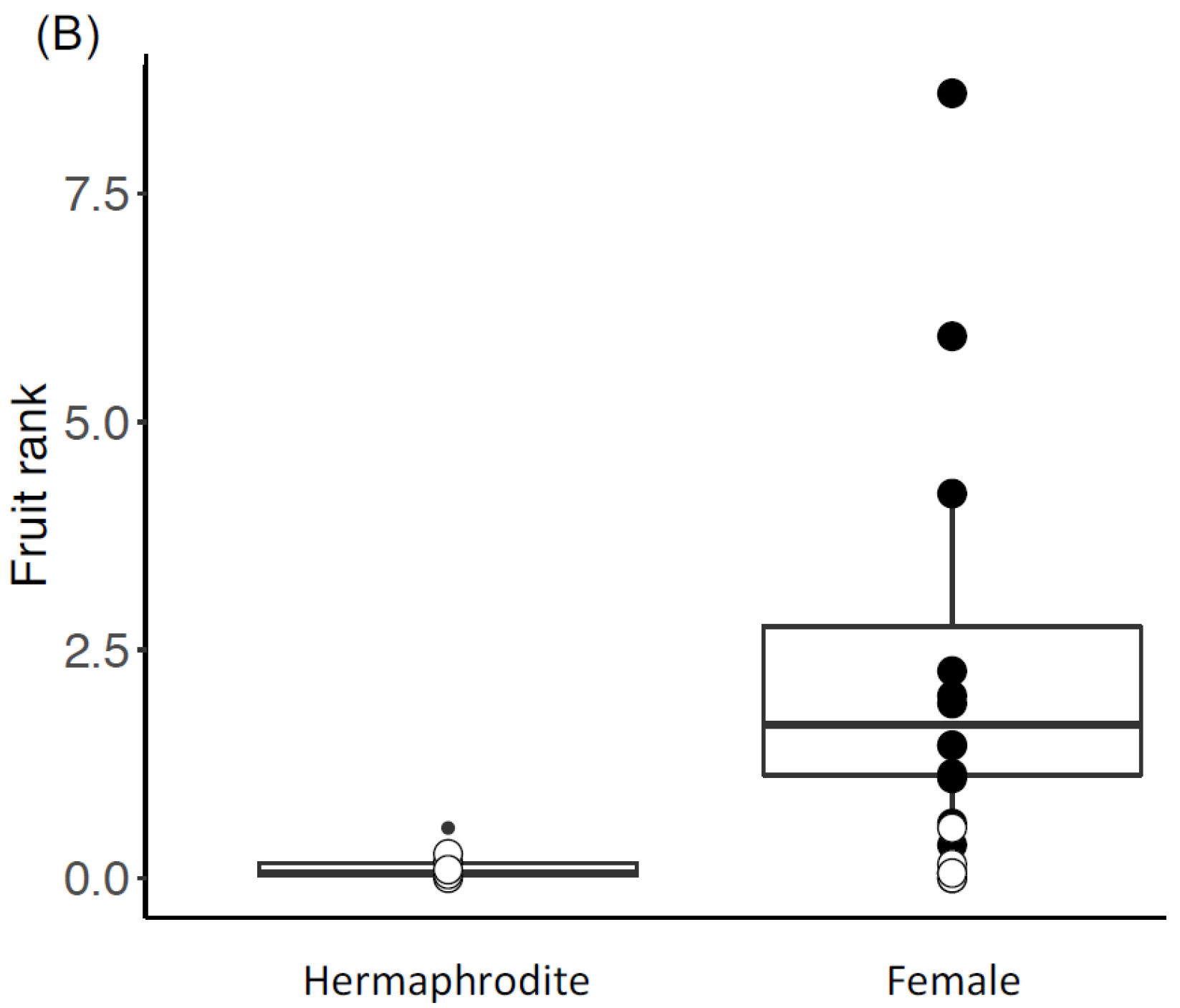

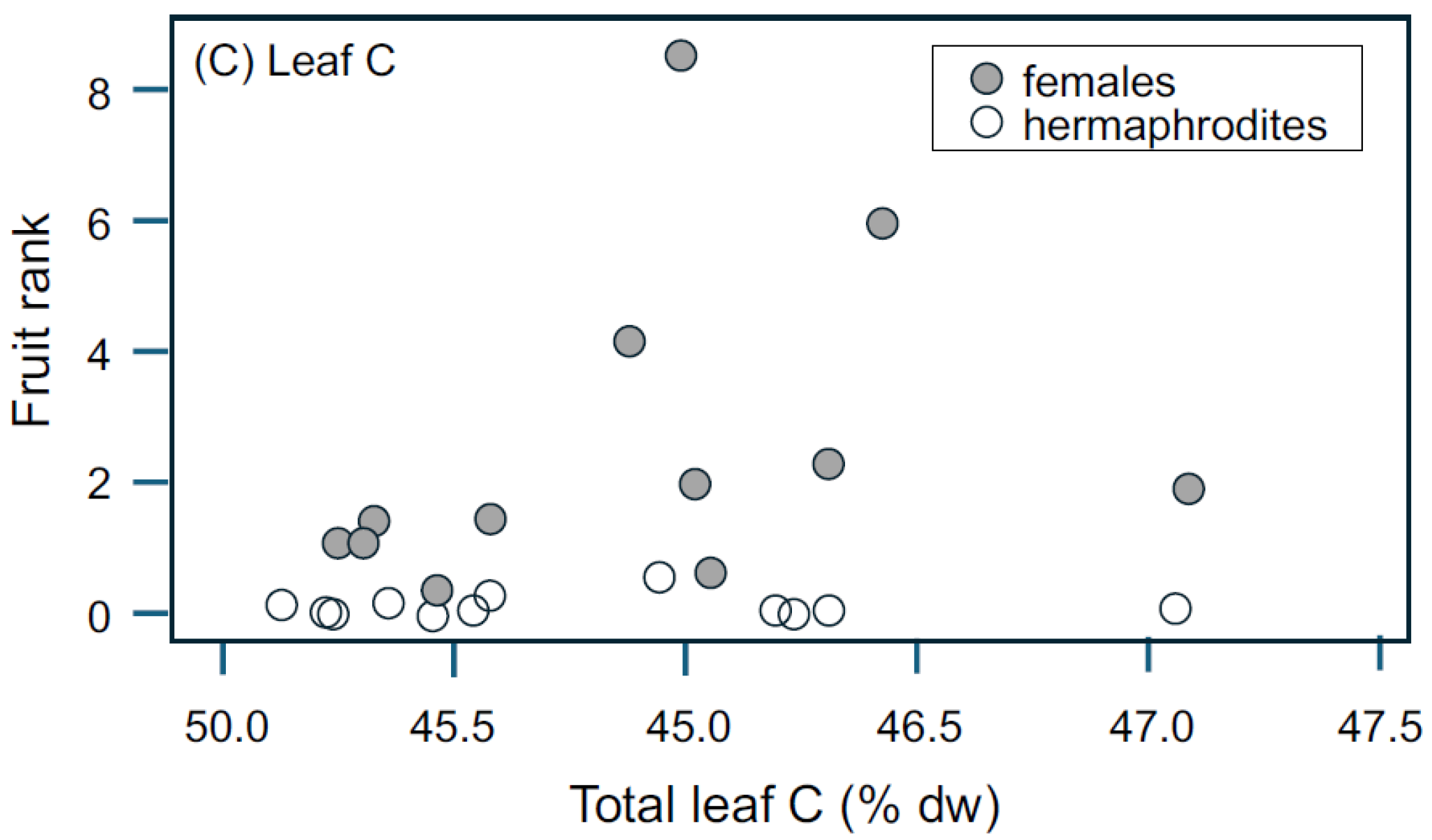

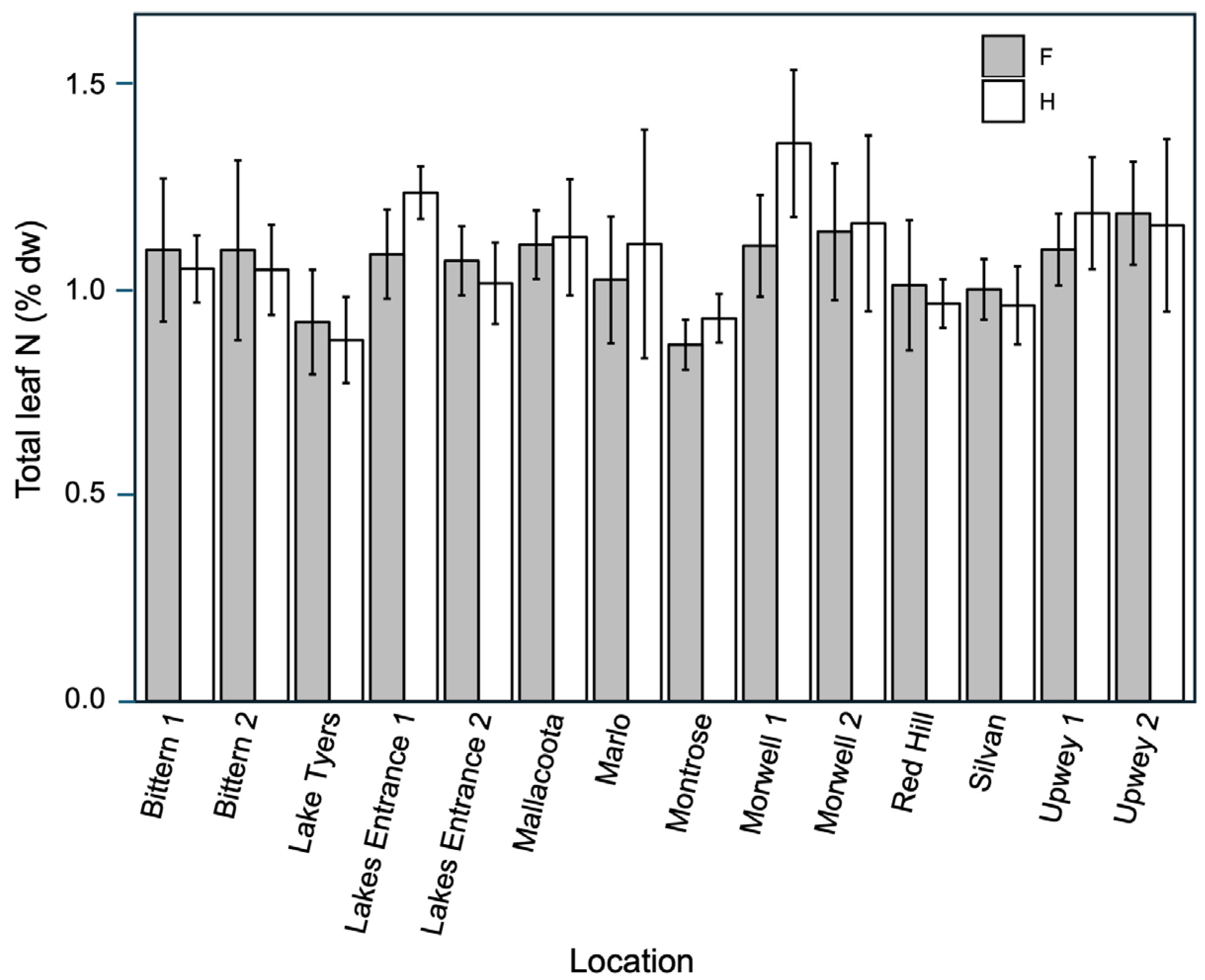

3.2. Resource Availability: Tree Density and Leaf N, C, and δC13

4. Discussion

4.1. The Proportion of Female and Hermaphrodite Trees Was Similar Across All Sites

4.2. Fruit Production Was Higher in Female Trees in the Native Range

4.3. Seed Size Was Greater in the Invasive Range

4.4. Influence of Resources on Seed and Fruit Production

5. Conclusions: Management and Control of P. undulatum

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barrett, S.C.H.; Colautti, R.I.; Eckert, C.G. Plant reproductive systems and evolution during biological invasion. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, J.H.; Pardini, E.A.; Schutzenhofer, M.R.; Chung, Y.A.; Seidler, K.J.; Knight, T.M. Greater sexual reproduction contributes to differences in demography of invasive plants and their noninvasive relatives. Ecology 2013, 94, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petanidou, T.; Godfree, R.C.; Song, D.S.; Kantsa, A.; Dupont, Y.L.; Waser, N.M. Self-compatibility and plant invasiveness: Comparing species in native and invasive ranges. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2012, 14, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Davis, R.; Connallon, T.; Gleadow, R.M.; Moore, J.L.; Uesugi, A. Multivariate selection mediated by aridity predicts divergence of drought-resistant traits along natural aridity gradients of an invasive weed. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrinos, J.G. How interactions between ecology and evolution influence contemporary invasion dynamics. Ecology 2004, 85, 2061–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.C.H. Why reproductive systems matter for the invasion biology of plants. In Fifty Years of Invasion Ecology: The Legacy of Charles Elton; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, A.; Brisson, J.; Belzile, F.; Turgeon, J.; Lavoie, C. Strategies for a successful plant invasion: The reproduction of Phragmites australis in north-eastern North America. J. Ecol. 2015, 103, 1529–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, H.G. Self compatibility and establishment after long distance dispersal. Evolution 1955, 9, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossenbacher, D.L.; Brandvain, Y.; Auld, J.R.; Burd, M.; Cheptou, P.O.; Conner, J.K.; Grant, A.G.; Hovick, S.M.; Pannell, J.R.; Pauw, A.; et al. Self-compatibility is over-represented on islands. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannell, J.R.; Auld, J.R.; Brandvain, Y.; Burd, M.; Busch, J.W.; Cheptou, P.O.; Conner, J.K.; Goldberg, E.E.; Grant, A.G.; Grossenbacher, D.L.; et al. The scope of Baker’s law. New Phytol. 2015, 208, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppley, S.M.; Pannell, J.R. Density-dependent self-fertilization and male versus hermaphrodite siring success in an androdioecious plant. Evolution 2007, 61, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannell, J. The maintenance of gynodioecy and androdioecy in a metapopulation. Evolution 1997, 51, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eppley, S.M.; Pannell, J.R. Sexual systems and measures of occupancy and abundance in an annual plant: Testing the metapopulation model. Am. Nat. 2007, 169, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossdorf, O.; Auge, H.; Lafuma, L.; Rogers, W.E.; Siemann, E.; Prati, D. Phenotypic and genetic differentiation between native and introduced plant populations. Oecologia 2005, 144, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannell, J.R.; Dorken, M.E.; Pujol, B.; Berjano, R. Gender variation and transitions between sexual systems in Mercurialis annua (Euphorbiaceae). Int. J. Plant Sci. 2008, 169, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufay, M.; Billard, E. How much better are females? The occurrence of female advantage, its proximal causes and its variation within and among gynodioecious species. Ann. Bot. 2012, 109, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Yamashita, N.; Tanaka, N.; Kushima, H. Sex ratio variation of Bischofia javanica Bl. (Euphorbiaceae) between native habitat, Okinawa (Ryukyu Islands), and invaded habitat, Ogasawara (Bonin Islands). Int. J. Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 1011–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.C.; Harper, K.T.; Charnov, E.L. Sex change in plants—Old and new observations and new hypotheses. Oecologia 1980, 47, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delph, L.F.; Wolf, D.E. Evolutionary consequences of gender plasticity in genetically dimorphic breeding systems. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.C.; McArthur, E.D.; Harper, K.T.; Blauer, A.C. Influence of environment on the floral sex-ratio of monoecious plants. Evolution 1981, 35, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, D.C.; Klikoff, L.G.; Harper, K.T. Differential resource utilization by sexes of dioecious plants. Science 1976, 193, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierzychudek, P.; Eckhart, V. Spatial segregation of the sexes of dioecious plants. Am. Nat. 1988, 132, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.A.; Grime, J.P.; Thompson, K. Fluctuating resources in plant communities: A general theory of invasibility. J. Ecol. 2000, 88, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis, J.M.J.; Dytham, C. Dispersal evolution during invasions. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2002, 4, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, A.D.; Thomas, C.D. Changes in dispersal during species’ range expansions. Am. Nat. 2004, 164, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, S.; Leishman, M.R. Have your cake and eat it too: Greater dispersal ability and faster germination towards range edges of an invasive plant species in eastern Australia. Biol. Invasions 2018, 20, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.L.; Brown, G.P.; Shine, R. Life-history evolution in range-shifting populations. Ecology 2010, 91, 1617–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwynar, L.C.; Macdonald, G.M. Geographical variation of lodgepole pine in relation to population history. Am. Nat. 1987, 129, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naniwadekar, R.; Mishra, C.; Datta, A. Fruit resource tracking by hornbill species at multiple scales in a tropical forest in India. J. Trop. Ecol. 2015, 31, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoby, M.; Leishman, M.; Lord, J. Comparative ecology of seed size and dispersal. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 1996, 351, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, L.A.; Rees, M.; Crawley, M.J. Seed mass and the competition/colonization trade-off: A sowing experiment. J. Ecol. 1999, 87, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleadow, R.M.; Ashton, D.H. Invasion by Pittosporum undulatum of the forests of central Victoria. I Invasion patterns and plant morphology. Aust. J. Bot. 1981, 29, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.; Burd, M.; Venn, S.E.; Gleadow, R. Integrating the Passenger-Driver hypothesis and plant community functional traits to the restoration of lands degraded by invasive trees. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 408, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, D.; Nascimento, L.B.D.; Brunetti, C.; Ferrini, F.; Gleadow, R.M. Is the invasiveness of Pittosporum undulatum in eucalypt forests explained by the wide-ranging effects of its secondary metabolites? Forests 2023, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleadow, R.M. Invasion by Pittosporum undulatum of the forests of central Victoria. II Dispersal, germination and establishment. Aust. J. Bot. 1982, 30, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.A.; Burd, M.; Venn, S.E.; Gleadow, R.M. Bird community recovery following removal of an invasive tree. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2021, 2, e12080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Fairweather, P.G. Changes in floristic composition of urban bushland invaded by Pittosporum undulatum in northern Sydney, Australia. Aust. J. Bot. 1997, 45, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, R.V.; Leishman, M.R. Invasive plants and invaded ecosystems in Australia: Implications for biodiversity. In Austral Ark: The State of Wildlife in Australia and New Zealand; Stow, A., Maclean, N., Holwell, G.I., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 105–133. [Google Scholar]

- Fensham, R.J.; Laffineur, B. Defining the native and naturalised flora for the Australian continent. Aust. J. Bot. 2019, 67, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silcock, J.L. Aboriginal translocations: The intentional propagation and dispersal of plants in Aboriginal Australia. J. Ethnobiol. 2025, 38, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiven, I.J.; Russell, L. First Knowledges Innovation: Knowledge and Ingenuity; Thames and Hudson: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Goodland, T.; Healey, J.R. The Invasion of Jamaican Montane Rainforests by the Australian Tree Pittosporum Undulatum; School of Agricultural and Forest Sciences, University of Wales: Wales, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hortal, J.; Borges, P.A.V.; Jiménez-Valverde, A.; de Azevedo, E.B.; Silva, L. Assessing the areas under risk of invasion within islands through potential distribution modelling: The case of Pittosporum undulatum in Sao Miguel, Azores. J. Nat. Conserv. 2010, 18, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, P.; Medeiros, V.; Gil, A.; Silva, L. Distribution, habitat and biomass of Pittosporum undulatum, the most important woody plant invader in the Azores Archipelago. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokotjomela, T.M.; Musil, C.F.; Esler, K.J. Frugivorous birds visit fruits of emerging alien shrub species more frequently than those of native shrub species in the South African Mediterranean climate region. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2013, 86, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullett, T.L. Ecological aspects of Sweet Pittosporum (Pittosporum undulatum Vent.): Implications for control and management. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Australian Weeds Conference, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 30 September–3 October 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gleadow, R.M.; Walker, J. The invasion of Pittosporum undulatum in the Dandenong Ranges, Victoria: Realising predictions about rates and impact. Plant Prot. Q. 2014, 29, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gleadow, R.M.; Rowan, K.S. Invasion by Pittosporum undulatum of the forests of central Victoria. III Effects of temperature and light on growth and drought resistance. Aust. J. Bot. 1982, 30, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. Influence of suburban edges on invasion of Pittosporum undulatum into the bushland of northern Sydney, Australia. Aust. J. Ecol. 1997, 22, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingham, P.J.; Tanner, E.V.J.; Martin, P.H.; Healey, J.R.; Burge, O.R. Endemic trees in a tropical biodiversity hotspot imperilled by an invasive tree. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 217, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullett, T.L. Effects of the native environmental weed Pittosporum undulatum Vent. (Sweet Pittosporum) on plant biodiversity. Plant Prot. Q. 2001, 16, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Blossey, B.; Notzold, R. Evolution of increased competitive ability in invasive nonindigenous plants—A hypothesis. J. Ecol. 1995, 83, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, R.M.; Crawley, M.J. Exotic plant invasions and the enemy release hypothesis. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002, 17, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejda, M.; Pysek, P.; Pergl, J.; Sádlo, J.; Chytry, M.; Jarosík, V. Invasion success of alien plants: Do habitat affinities in the native distribution range matter? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009, 18, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Etten, M.L.; Conner, J.K.; Chang, S.M.; Baucom, R.S. Not all weeds are created equal: A database approach uncovers differences in the sexual system of native and introduced weeds. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 2636–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hierro, J.L.; Maron, J.L.; Callaway, R.M. A biogeographical approach to plant invasions: The importance of studying exotics in their introduced and native range. J. Ecol. 2005, 93, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hierro, J.L.; Villarreal, D.; Eren, Ö.; Graham, J.M.; Callaway, R.M. Disturbance facilitates invasion: The effects are stronger abroad than at home. Am. Nat. 2006, 168, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sax, D.F.; Stachowicz, J.J.; Brown, J.H.; Bruno, J.F.; Dawson, M.N.; Gaines, S.D.; Grosberg, R.K.; Hastings, A.; Holt, R.D.; Mayfield, M.M.; et al. Ecological and evolutionary insights from species invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2007, 22, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, D.L.; Pickup, M.; Barrett, S.C.H. Comparative analyses of sex-ratio variation in dioecious flowering plants. Evolution 2013, 67, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuñez, M.A.; Horton, T.R.; Simberloff, D. Lack of belowground mutualisms hinders Pinaceae invasions. Ecology 2009, 90, 2352–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.G.; Kalisz, S.; Geber, M.A.; Sargent, R.; Elle, E.; Cheptou, P.O.; Goodwillie, C.; Johnston, M.O.; Kelly, J.K.; Moeller, D.A.; et al. Plant mating systems in a changing world. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, M.J.; Harvey, P.H.; Purvis, A. Comparative ecology of the native and alien floras of the British Isles. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 1996, 351, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daws, M.I.; Hall, J.; Flynn, S.; Pritchard, H.W. Do invasive species have bigger seeds? Evidence from intra- and inter-specific comparisons. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2007, 73, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M.; Montesinos, D.; French, K.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, S. Evidence for enemy release and increased seed production and size for two invasive Australian acacias. J. Ecol. 2016, 104, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejmfinek, M. A theory of seed plant invasiveness: The first sketch. Biol. Conserv. 1996, 78, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.A.B.; Cooke, J.; Moles, A.T.; Leishman, M.R. Reproductive output of invasive versus native plants. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2008, 17, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller-Landau, H.C. The tolerance-fecundity trade-off and the maintenance of diversity in seed size. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4242–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kleunen, M.; Dawson, W.; Maurel, N. Characteristics of successful alien plants. Mol. Ecol. 2015, 24, 1954–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.P.; Emlen, J.; Freeman, D.C. Biased sex ratios in plants: Theory and trends. Bot. Rev. 2012, 78, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.S.; Pannell, J.R. Roots, shoots and reproduction: Sexual dimorphism in size and costs of reproductive allocation in an annual herb. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2008, 275, 2595–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, P.; Houston, K.; Evans, T. Shifts in seed size across experimental nitrogen enrichment and plant density gradients. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2009, 10, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbell, S.P. Seed predation and the coexistence of tree species in tropical forests. OIKOS 1980, 35, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Origin | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation (m) | Ave Min Temp °C | Ave Max Temp °C | Ave Rainfall (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morwell National Park 1 a | Native | Lat: −38.36 | Lon: 146.40 | 184 | 8.0 | 20.2 | 736.7 |

| Morwell National Park 2 a | Native | Lat: −38.36 | Lon: 146.40 | 184 | 8.0 | 20.2 | 736.7 |

| Lakes Entrance 1 b | Native | Lat: −37.88 | Lon: 147.96 | 40 | 10.4 | 19.7 | 733.6 |

| Lakes Entrance 2 b | Native | Lat: −37.88 | Lon: 147.96 | 40 | 10.4 | 19.7 | 733.6 |

| Lake Tyers State park b | Native | Lat: −37.76 | Lon: 148.07 | 89 | 8.3 | 20.1 | 729.9 |

| Marlo c | Native | Lat: −37.79 | Lon: 148.55 | 22 | 8.8 | 20.2 | 845.5 |

| Mallacoota d | Native | Lat: −37.56 | Lon: 149.76 | 19 | 11.0 | 19.6 | 943.7 |

| Red Hill e | Invaded | Lat: −38.39 | Lon: 145.02 | 131 | 9.9 | 19.9 | 708.4 |

| Bittern 1 e | Invaded | Lat: −38.30 | Lon: 145.12 | 81 | 9.9 | 19.9 | 708.4 |

| Bittern 2 e | Invaded | Lat: −38.30 | Lon: 145.12 | 81 | 9.9 | 19.9 | 708.4 |

| Upwey 1 f | Invaded | Lat: −37.90 | Lon: 145.31 | 291 | 9.6 | 19.7 | 855.4 |

| Upwey 2 f | Invaded | Lat: −37.90 | Lon: 145.31 | 291 | 9.6 | 19.7 | 855.4 |

| Montrose f | Invaded | Lat: −37.84 | Lon: 145.33 | 222 | 9.6 | 19.7 | 855.4 |

| Silvan f | Invaded | Lat: −37.83 | Lon: 145.42 | 293 | 9.6 | 19.7 | 855.4 |

| Trees | Females | Seed Number | Seed Mass (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native populations | ||||

| Morwell 1 | 30 | 10 | 32.0 ± 1.8 | 0.0023 ± 0.0003 |

| Morwell 2 | 8 | 5 | 28.0 ± 3.6 | 0.0020 ± 0.0001 |

| Lakes Entrance 1 | 103 | 46 | 33.8 ± 1.3 | 0.0036 ± 0.0003 |

| Lakes Entrance 2 | 34 | 16 | 27.1 ± 3.6 | 0.0038 ± 0.0001 |

| Lake Tyers | 22 | 8 | 25.0 ± 1.4 | 0.0029 ± 0.0026 |

| Marlo | 62 | 34 | 27.3 ± 4.9 | 0.0040 ± 0.0014 |

| Mallacoota | 143 | 71 | 28.7 ± 5.7 | 0.0027 ± 0.0006 |

| Invasive populations | ||||

| Red Hill | 159 | 72 | 27.6 ± 4.0 | 0.0082 ± 0.0026 |

| Bittern 1 | 51 | 15 | N/A | |

| Bittern 2 | 89 | 44 | N/A | |

| Upwey 1 | 30 | 14 | 26.8 ± 4.2 | 0.0071 ± 0.0017 |

| Upwey 2 | 29 | 12 | 28.7 ± 5.4 | 0.0066 ± 0.0016 |

| Montrose | 84 | 31 | 27.9 ± 4.7 | 0.0028 ± 0.0009 |

| Silvan | 27 | 10 | N/A | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

O’Leary, B.; Burd, M.; Venn, S.; Gleadow, R.M. Reproductive Investment Across Native and Invasive Regions in Pittosporum undulatum Vent., a Range Expanding Gynodioecious Tree. Forests 2026, 17, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010072

O’Leary B, Burd M, Venn S, Gleadow RM. Reproductive Investment Across Native and Invasive Regions in Pittosporum undulatum Vent., a Range Expanding Gynodioecious Tree. Forests. 2026; 17(1):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010072

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Leary, Ben, Martin Burd, Susanna Venn, and Roslyn M. Gleadow. 2026. "Reproductive Investment Across Native and Invasive Regions in Pittosporum undulatum Vent., a Range Expanding Gynodioecious Tree" Forests 17, no. 1: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010072

APA StyleO’Leary, B., Burd, M., Venn, S., & Gleadow, R. M. (2026). Reproductive Investment Across Native and Invasive Regions in Pittosporum undulatum Vent., a Range Expanding Gynodioecious Tree. Forests, 17(1), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010072