Empowering Health Through Digital Lifelong Prevention: An Umbrella Review of Apps and Wearables for Nutritional Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Critical Appraisal

3. Results

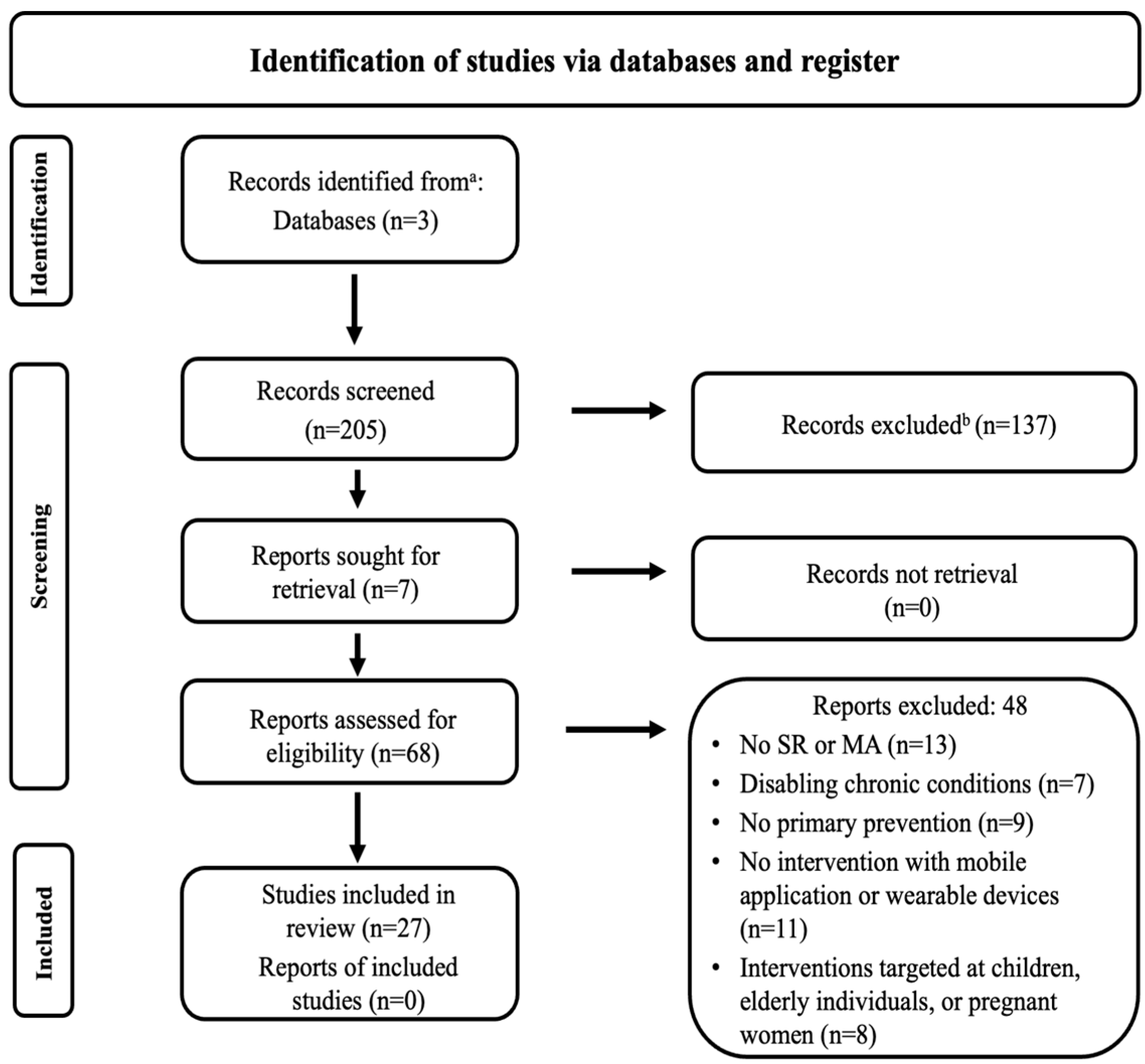

3.1. Search Flow Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Reviews

Main Outcomes of the Included Reviews

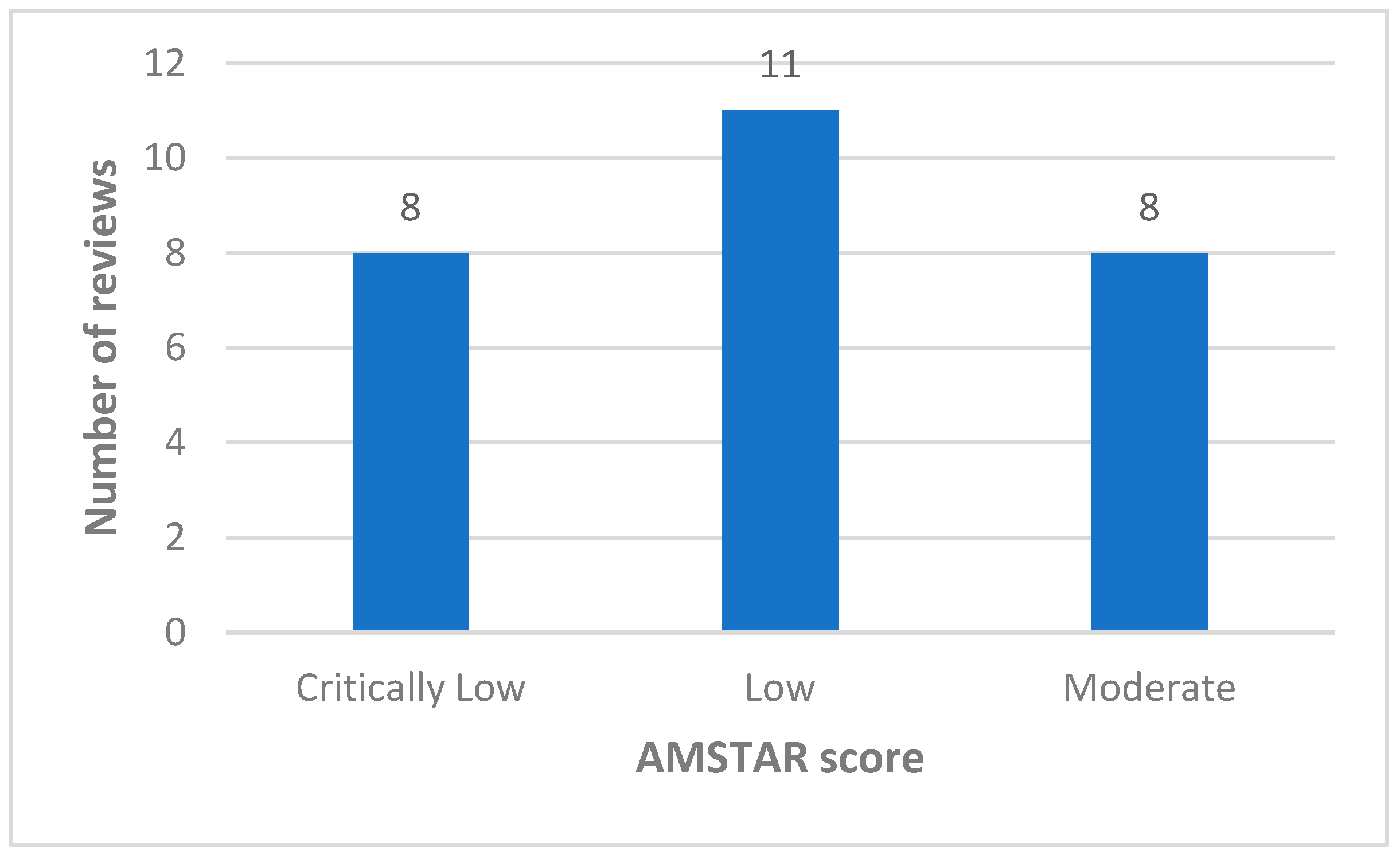

3.3. Methodological Quality

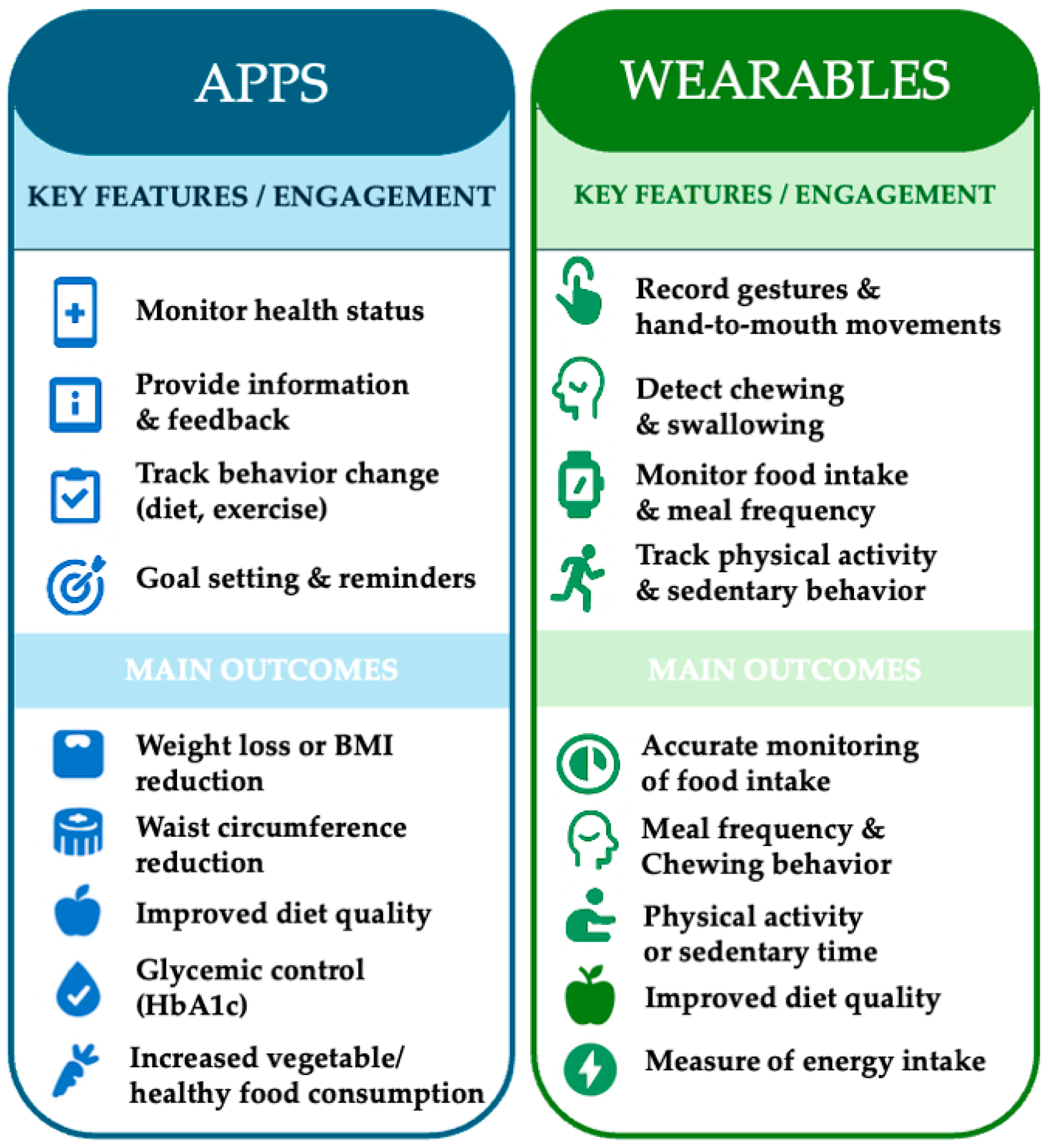

3.4. App and Wearable Device-Based Health Promotion Interventions

3.4.1. App-Based Interventions and Their Outcomes

| Author, Year | Sample Size Total | Experimental Group | Control Group | App Name | Platform | App Purpose | Intervention Period | Major Outcome Indices | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee, W. et al., 2010 | 36 | 19 | 17 | SmartDiet | App Store | -Monitor health status and behavior change -Dietary quality -Provide information | 6 Weeks | -Fat mass -Body weight -a BMI | [37] |

| Carter, M.C. et al., 2013 | 129 | 43 (App) | 86 (Web, paper diaries) | My Meal Mate App | b N/A | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor health status | 6 months | Weight loss | [51] |

| Van Drongelen, A. et al., 2014 | 502 | 251 (App, website) | 251 (Website) | MORE Energy App | Play store | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor behavior change | 6 months | -Snacking behavior -Physical activity -Sleep quality | [38] |

| Laing, B.Y. et al., 2014 | 212 | 105 (App, usual care) | 107 (Usual care) | MyFitnessPal App | App store/Play store | -Monitor behavior change | 6 months | -Self-monitoring adherence | [52] |

| Nollen, N.L. et al., 2014 | 51 | 26 (app) | 25 | MyPal A626 | Microsoft Store | -Weight control -Monitor behavior change -Provide information, feedback | 12 weeks | -Increase fruit and vegetables -Decreasing sugar drink | [60] |

| Wharton, C.M. et al., 2014 | 34 | 19 (mobile app) | 15 (paper and pencil) | Lose It! | App Store/Play Store | -Monitor health status and behavior change | 8 weeks | -Weight loss | [39] |

| Gilliland, J. et al., 2015 | 208 | N/A | N/A | SmartAPPetite | Play Store | -Dietary quality -Provide information -Monitor behavior change | 10 weeks | -Healthy food consumption | [40] |

| Hales, S. et al., 2016 | 51 | 26 (c TBP + App Social) | 25 (TBP + App Standard) | Social POD app | N/A | -Provide information -Monitor health status | 12 weeks | -Weight loss -BMI | [41] |

| Allman-Farinelli, M. et al., 2016 | 250 | 125 (App, SMS, call, e-mail) | 125 (call, SMS) | TXT2BFiT | N/A | -Dietary quality -Monitor health status and behavior change | 12 weeks | -Weight loss -Improvement in eating behavior | [61] |

| Zhou, W. et al., 2016 | 100 | 50 (app) | 50 (standard of care) | Welltang | N/A | -Reduce HbA1c level -Improve diabetes status -Monitor health status | 3 months | -Improvements in HbA1c -Improvements in glycemia -Knowledge of diabetes and self-care behaviors | [42] |

| Bentley, C.L. et al., 2016 | 27 | 9 (app) | 18 (no app) | AiperMotion | N/A | -Reduce HbA1c level | 12 weeks | -Reduce HbA1c levels -Weight loss | [50] |

| Godino, J.G. et al., 2016 | 404 | 202 (Mobile app, facebook, text messaging, emails, website) | 202 (Website, emails) | GoalGetter App, BeHealthy App TrendSetter App | App Store/Play Store | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor Health Behavior | 12 months | -Body weight, -BMI, -Waist circumference -Blood pressure | [43] |

| Elbert S.P. et al., 2016 | 146 | 146 | N/A | Fruit and Vegetables hAPP | Play store | -Monitor behavior change -Dietary quality -Predict fruit and vegetable intake | 6 months | -Intake of fruits and vegetables | [62] |

| Mummah, S.A. et al., 2016 | 17 | 8 | 9 | Vegethon App | N/A | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor behavior change -Increase vegetable consumption | 12 weeks | -Daily vegetable consumption | [57] |

| Martin, C.K. et al., 2017 | 40 | 20 (smartphone) | 20 (usual care) | SmartLoss | N/A | -Provide information -Dietary quality -Monitor health status | 16 weeks | -Weight loss | [53] |

| Balk-Møller, N.C. et al., 2017 | 566 | 355 (app) | 211 (no app) | Sosu-life | N/A | -Monitor health status | 38 weeks | -Weight loss -Body fat -Waist circumference | [44] |

| Spring, B. et al., 2017 | 96 | 96 (Self-guided, standard or technology-supported) | N/A | ENGAGED | N/A | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor health status | 6 months | -Body weight -Self-monitoring adherence | [54] |

| Mummah, S. et al., 2017 | 135 | 68 | 67 | Vegethon App | N/A | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor behavior change | 8 weeks | -Increased intake of vegetables | [58] |

| Hull, P. et al., 2017 | 80 | 80 (App) | N/A | CHEW App | N/A | -Nutrition education | 3 months | -Dietary quality -Healthy snacks and beverages intake | [63] |

| Ipjian M.L. et al., 2017 | 30 | 15 (App, website, dietary sodium intake, verbal instruction) | 15 (Journal, dietary sodium intake, verbal instruction) | MyFitnessPal App | App store/Play store | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor behavior change | 4 weeks | -Urinary sodium excretion | [59] |

| Clarke, P. et al., 2019 | 300 | 189 | 111 | VeggieBook | App Store | -Dietary quality -Monitor behavior change | 10 weeks | -Increased use of different types of vegetables | [45] |

| Ambrosini, G.L. et al., 2018 | 50 | 50 | N/A | Easy Diet Diary App | App store | -Monitor behavior change | 1 Week | -Energy supply -Sugar intake | [64] |

| Delisle Nyström, C. et al., 2018 | 263 | 133 (App, push notifications, graphical feedback) | 130 (Pamphlet) | MINISTOP App | App store/Play store | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor health status | 12 months | -BMI -Fruits and vegetables intake -Reduced candy, and sweetened beverages | [55] |

| Haas, K. et al., 2019 | 43 | 43 (app) | N/A | Ovivia App | App Store/Play Store | -Dietary quality -Provide information -Monitor health status and behavior change | 6 months | -Weight loss -BMI -Waist circumference -Body fat -Blood pressure -Eating habits | [46] |

| Patel, M.L. et al., 2019 | 105 | 105 (App, e-mail) | N/A | MyFitnessPal | App store/Play store | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor health status | 12 weeks | -Weight loss -Self-monitoring adherence | [56] |

| Eyles, H. et al., 2017 | 66 | 33 (app) | 33 (usual care) | SaltSwitch | N/A | -Dietary quality -Monitor behavior change | 4 weeks | -Significant reduction in purchases of salty foods | [47] |

| Rosas, L.G. et al., 2020 | 191 | 92 (App, website, usual care, activity tracker) | 99 (Usual care, activity tracker) | MyFitnessPal | App store/Play store | -Provide information, feedback -Monitor health status | 24 months | -Body weight -Waist circumference -Psychosocial well-being | [49] |

| Eisenhauer, C.M. et al., 2021 | 80 | 40 (mobile plus) | 40 (mobile basic) | Lose-It! | App Store/Play Store | -Dietary quality -Monitor health status | 6 months | -Weight loss | [48] |

3.4.2. Wearable-Based Interventions and Their Outcomes

| Author, Year | Sample Size Total | Experimental Group | Control Group | App Name | Platform | App Purpose | Intervention Period | Major outcome Indices | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dong, Y. et al., 2012 | 102 | a N/A | N/A | -Gyroscope | -InertiaCube3 by InterSense | -Record the hand-to-mouth gestures | 24 h | -Capture chewing motion -Monitor the number of daily meals | [68] |

| Päßler, S. et al., 2012 | 51 | N/A | N/A | -Microphone | -FG-23329-CO5 by Knowles Acoustics | -Monitor the food intake of subjects in therapy -Differentiate kinds of food consumed | 24 h | -Register chewing noises | [69] |

| Doherty, A.R. et al., 2013 | N/A | N/A | N/A | -Wearable camera | -Microsoft SenseCam | -Measure sedentary behaviour -Monitor nutrition-related behaviours | 24 h | -Monitor food intake -Monitor physical activity | [65] |

| Gemming, L. et al., 2015 | 40 | N/A | N/A | -Wearable camera | -Microsoft SenseCam | -Assess kilocalories consumed (energy intake) -Monitor health behaviours | 15 days | -Take pictures of daily meals -Measure of energy intake | [66] |

| McClung, H.L. et al., 2018 | N/A | N/A | N/A | -Microphones -Smart eyeglasses with electromyography electrodes -Motion sensors -Wearable biosensors | -InertiaCube3 -FG-23329-CO5 by Knowles Acoustics | -Assess food intake -Monitor subjects following a healthy nutritional plan -Make the difference between solid and liquid food | 24 h | -Detect food crushing -Register swallowing frequency -Register muscle activations -Record hand-to-mouth gestures | [67] |

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SR | Systematic Review |

| MA | Meta-Analysis |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| AMSTAR | A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews |

| BCT | Behavioral change techniques |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| LIPA | Light-Intensity Physical Activity |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| HbA1 | Hemoglobin A1c |

| FPG | Fasting Plasma Glucose |

| VO2max | Maximal Oxygen Consumption |

| HDL-C | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| FV | Fruit and Vegetable |

| TBP | Theory-Based Podcast |

References

- Ringeval, M.; Wagner, G.; Denford, J.; Paré, G.; Kitsiou, S. Fitbit-based interventions for healthy lifestyle outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e23954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Free, C.; Phillips, G.; Watson, L.; Galli, L.; Felix, L.; Edwards, P.; Patel, V.; Haines, A. The effectiveness of mobile-health technologies to improve health care service delivery processes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, G.C.; Accardi, G.; Monastero, R.; Nicoletti, F.; Libra, M. Ageing: From inflammation to cancer. Immun. Ageing 2018, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixit, S.; Nandakumar, G. Promoting healthy lifestyles using information technology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 22, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthsatz, M.; Candeias, V. Non-communicable disease prevention, nutrition and aging. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 379–388. [Google Scholar]

- Villinger, K.; Wahl, D.R.; Boeing, H.; Schupp, H.T.; Renner, B. The effectiveness of app-based mobile interventions on nutrition behaviours and nutrition-related health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1465–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandracchia, F.; Llauradó, E.; Tarro, L.; Del Bas, J.M.; Valls, R.M.; Pedret, A.; Radeva, P.; Arola, L.; Solà, R.; Boqué, N. Potential use of mobile phone applications for self-monitoring and increasing daily fruit and vegetable consumption: A systematized review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddison, R.; Cartledge, S.; Rogerson, M.; Goedhart, N.S.; Singh, T.R.; Neil, C.; Phung, D.; Ball, K. Usefulness of wearable cameras as a tool to enhance chronic disease self-management: Scoping review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e10371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbasis, L.; Bellou, V.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Conducting umbrella reviews. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.M.; Maher, C.A.; Vandelanotte, C.; Hingle, M.; Middelweerd, A.; Lopez, M.L.; DeSmet, A.; Short, C.E.; Nathan, N.; Hutchesson, M.J.; et al. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and diet-related eHealth and mHealth research: Bibliometric analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M.; Adam, P.C.; Smolenski, D.J.; Wong, H.T.; de Wit, J.B. A meta-analysis of overall effects of weight loss interventions delivered via mobile phones and effect size differences according to delivery mode, personal contact, and intervention intensity and duration. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, G.F.; Granado-Font, E.; Ferré-Grau, C.; Montaña-Carreras, X. Mobile phone apps to promote weight loss and increase physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semper, H.M.; Povey, R.; Clark-Carter, D. A systematic review of the effectiveness of smartphone applications that encourage dietary self-regulatory strategies for weight loss in overweight and obese adults. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeppe, S.; Alley, S.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Bray, N.A.; Williams, S.L.; Duncan, M.J.; Vandelanotte, C. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Füzéki, E.; Engeroff, T.; Banzer, W. Health benefits of light-intensity physical activity: A systematic review of accelerometer data of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1769–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesch, K.C.; Hill, R.L.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; van Uffelen, J.G.Z.; Pavey, T. Validity of objective methods for measuring sedentary behaviour in older adults: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Cho, M.; Jang, J.; Jang, H. Mobile app-based health promotion programs: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarnowiecki, D.; Mauch, C.E.; Middleton, G.; Matwiejczyk, L.; Watson, W.L.; Dibbs, J.; Dessaix, A.; Golley, R.K. A systematic evaluation of digital nutrition promotion websites and apps for supporting parents to influence children’s nutrition. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramastri, R.; Pratama, S.A.; Ho, D.K.N.; Purnamasari, S.D.; Mohammed, A.Z.; Galvin, C.J.; Hsu, Y.E.; Tanweer, A.; Humayun, A.; Househ, M.; et al. Use of mobile applications to improve nutrition behaviour: A systematic review. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2020, 192, 105459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.S.; Hyde, E.T.; Bassett, D.R.; Carlson, S.A.; Carnethon, M.R.; Ekelund, U.; Evenson, K.R.; Galuska, D.A.; Kraus, W.E.; Lee, I.M.; et al. Systematic review of the prospective association of daily step counts with risk of mortality, cardiovascular disease, and dysglycemia. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavero-Redondo, I.; Martinez-Vizcaino, V.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, R.; Saz-Lara, A.; Pascual-Morena, C.; Álvarez-Bueno, C. Effect of behavioral weight management interventions using lifestyle mHealth self-monitoring on weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, D.J.; Su, X.; Gao, Z. Health wearable devices for weight and BMI reduction in individuals with overweight/obesity and chronic comorbidities: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2021, 55, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Erdt, M.; Lee, J.; Cao, Y.; Naharudin, N.B.; Theng, Y.L. Effectiveness of eHealth nutritional interventions for middle-aged and older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e15649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, A.; Shi, Y.; Bauman, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Validity of new technologies that measure bone-related dietary and physical activity risk factors in adolescents and young adults: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raber, M.; Liao, Y.; Rara, A.; Schembre, S.M.; Krause, K.J.; Strong, L.; Daniel-MacDougall, C.; Basen-Engquist, K. A systematic review of the use of dietary self-monitoring in behavioural weight loss interventions: Delivery, intensity and effectiveness. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5885–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevance, G.; Golaszewski, N.M.; Tipton, E.; Hekler, E.B.; Buman, M.; Welk, G.J.; Patrick, K.; Godino, J.G. Accuracy and precision of energy expenditure, heart rate, and steps measured by combined-sensing Fitbits against reference measures: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e35626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarry, A.; Rice, J.; O’Connor, E.M.; Tierney, A.C. Usage of mobile applications or mobile health technology to improve diet quality in adults. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Blake, H.; Crozier, A.J.; Dankiw, K.; Dumuid, D.; Kasai, D.; O’Connor, E.; Virgara, R.; et al. Effectiveness of wearable activity trackers to increase physical activity and improve health: A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Digit. Health 2022, 4, e615–e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, H.S.J.; Koh, W.L.; Ng, J.S.H.Y.; Tan, K.K. Sustainability of weight loss through smartphone apps: Systematic review and meta-analysis on anthropometric, metabolic, and dietary outcomes. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e40141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppes, E.V.; Augustyn, M.; Gross, S.M.; Vernon, P.; Caulfield, L.E.; Paige, D.M. Engagement with and acceptability of digital media platforms for use in improving health behaviors among vulnerable families: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e40934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, K.K.; Mergenthal, L.; Christianson, L.; Busskamp, A.; Vonstein, C.; Zeeb, H. Digital technologies for health promotion and disease prevention in older people: Scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, H.S.J.; Rajasegaran, N.N.; Chin, Y.H.; Chew, W.S.N.; Kim, K.M. Effectiveness of combined health coaching and self-monitoring apps on weight-related outcomes in people with overweight and obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e42432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgiu, M.; Ketelhut, S.; Kubica, C.; Nissen, R.; Doster, A.K.; Thron, M.; Timm, I.; Giurgiu, V.; Nigg, C.R.; Woll, A.; et al. Assessment of 24-hour physical behaviour in adults via wearables: A systematic review of validation studies under laboratory conditions. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoneye, C.L.; Kwasnicka, D.; Mullan, B.; Pollard, C.M.; Boushey, C.J.; Kerr, D.A. Dietary assessment methods used in adult digital weight loss interventions: A systematic literature review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2023, 36, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Chae, Y.M.; Kim, S.; Ho, S.H.; Choi, I. Evaluation of a mobile phone-based diet game for weight control. J. Telemed. Telecare 2010, 16, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Drongelen, A.; Boot, C.R.; Hlobil, H.; Twisk, J.W.; Smid, T.; van der Beek, A.J. Evaluation of an mHealth intervention aiming to improve health-related behavior and sleep and reduce fatigue among airline pilots. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2014, 40, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, C.M.; Johnston, C.S.; Cunningham, B.K.; Sterner, D. Dietary self-monitoring, but not dietary quality, improves with use of smartphone app technology in an 8-week weight loss trial. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, J.; Sadler, R.; Clark, A.; O’Connor, C.; Milczarek, M.; Doherty, S. Using a smartphone application to promote healthy dietary behaviours and local food consumption. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 841368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, S.; Turner-McGrievy, G.M.; Wilcox, S.; Fahim, A.; Davis, R.E.; Huhns, M.; Valafar, H. Social networks for improving healthy weight loss behaviors for overweight and obese adults: A randomized clinical trial of the social pounds off digitally (Social POD) mobile app. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 94, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, M.; Yuan, J.; Sun, Y. Welltang-A smartphone-based diabetes management application—Improves blood glucose control in Chinese people with diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 116, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godino, J.G.; Merchant, G.; Norman, G.J.; Donohue, M.C.; Marshall, S.J.; Fowler, J.H.; Calfas, K.J.; Huang, J.S.; Rock, C.L.; Griswold, W.G.; et al. Using social and mobile tools for weight loss in overweight and obese young adults (Project SMART): A 2 year, parallel-group, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balk-Møller, N.C.; Poulsen, S.K.; Larsen, T.M. Effect of a nine-month web- and app-based workplace intervention to promote healthy lifestyle and weight loss for employees in the social welfare and health care sector: A randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Evans, S.H.; Neffa-Creech, D. Mobile app increases vegetable-based preparations by low-income household cooks: A randomized controlled trial. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, K.; Hayoz, S.; Maurer-Wiesner, S. Effectiveness and feasibility of a remote lifestyle intervention by dietitians for overweight and obese adults: Pilot study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e12289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, H.; McLean, R.; Neal, B.; Jiang, Y.; Doughty, R.N.; McLean, R.; Ni Mhurchu, C. A salt-reduction smartphone app supports lower-salt food purchases for people with cardiovascular disease: Findings from the SaltSwitch randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, C.M.; Brito, F.; Kupzyk, K.; Yoder, A.; Almeida, F.; Beller, R.J.; Miller, J.; Hageman, P.A. Mobile health assisted self-monitoring is acceptable for supporting weight loss in rural men: A pragmatic randomized controlled feasibility trial. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, L.G.; Lv, N.; Xiao, L.; Lewis, M.A.; Venditti, E.M.J.; Zavella, P.; Azar, K.; Ma, J. Effect of a culturally adapted behavioral intervention for Latino adults on weight loss over 2 years: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2027744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, C.L.; Otesile, O.; Bacigalupo, R.; Elliott, J.; Noble, H.; Hawley, M.S.; Williams, E.A.W.; Cudd, P. Feasibility study of portable technology for weight loss and HbA1c control in type 2 diabetes. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2016, 16, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.C.; Burley, V.J.; Nykjaer, C.; Cade, J.E. Adherence to a smartphone application for weight loss compared to website and paper diary: Pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, B.Y.; Mangione, C.M.; Tseng, C.H.; Leng, M.; Vaisberg, E.; Mahida, M.; Bholat, M.; Glazier, E.; Morisky, D.E.; Bell, D.S.; et al. Effectiveness of a smartphone application for weight loss compared with usual care in overweight primary care patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 161, S5–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.K.; Gilmore, L.A.; Apolzan, J.W.; Myers, C.A.; Thomas, D.M.; Redman, L.M. Smartloss: A personalized mobile health intervention for weight management and health promotion. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, B.; Pellegrini, C.A.; Pfammatter, A.; Duncan, J.M.; Pictor, A.; McFadden, H.G.; Siddique, J.; Hedeker, D. Effects of an abbreviated obesity intervention supported by mobile technology: The ENGAGED randomized clinical trial. Obesity 2017, 25, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyström, C.D.; Sandin, S.; Henriksson, P.; Henriksson, H.; Maddison, R.; Löf, M. A 12-month follow-up of a mobile-based (mHealth) obesity prevention intervention in pre-school children: The MINISTOP randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 658. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, M.L.; Hopkins, C.M.; Brooks, T.L.; Bennett, G.G. Comparing self-monitoring strategies for weight loss in a smartphone app: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummah, S.A.; Mathur, M.; King, A.C.; Gardner, C.D.; Sutton, S. Mobile technology for vegetable consumption: A randomized controlled pilot study in overweight adults. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummah, S.; Robinson, T.N.; Mathur, M.; Farzinkhou, S.; Sutton, S.; Gardner, C.D. Effect of a mobile app intervention on vegetable consumption in overweight adults: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipjian, M.L.; Johnston, C.S. Smartphone technology facilitates dietary change in healthy adults. Nutrition 2017, 33, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollen, N.L.; Mayo, M.S.; Carlson, S.E.; Rapoff, M.A.; Goggin, K.J.; Ellerbeck, E.F. Mobile technology for obesity prevention: A randomized pilot study in racial- and ethnic-minority girls. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allman-Farinelli, M.; Partridge, S.R.; McGeechan, K.; Balestracci, K.; Hebden, L.; Wong, A.; Phongsavan, P.; Denney-Wilson, E.; Harris, M.F.; Bauman, A. A Mobile Health Lifestyle Program for Prevention of Weight Gain in Young Adults (TXT2BFiT): Nine-Month Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2016, 4, e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbert, S.P.; Dijkstra, A.; Oenema, A. A mobile phone app intervention targeting fruit and vegetable consumption: The efficacy of textual and auditory tailored health information tested in a randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, P.; Emerson, J.S.; Quirk, M.E.; Canedo, J.R.; Jones, J.L.; Vylegzhanina, V.; Schmidt, D.C.; Mulvaney, S.A.; Beech, B.M.; Briley, C.; et al. A smartphone app for families with preschool-aged children in a public nutrition program: Prototype development and beta-testing. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, G.L.; Hurworth, M.; Giglia, R.; Trapp, G.; Strauss, P. Feasibility of a commercial smartphone application for dietary assessment in epidemiological research and comparison with 24-h dietary recalls. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.R.; Hodges, S.E.; King, A.C.; Smeaton, A.F.; Berry, E.; Moulin, C.J.; Lindley, S.; Kelly, P.; Foster, C. Wearable cameras in health: The state of the art and future possibilities. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemming, L.; Rush, E.; Maddison, R.; Doherty, A.; Gant, N.; Utter, J.; Ni Mhurchu, C. Wearable cameras can reduce dietary under-reporting: Doubly labelled water validation of a camera-assisted 24 h recall. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClung, H.L.; Ptomey, L.T.; Shook, R.P.; Aggarwal, A.; Gorczyca, A.M.; Sazonov, E.S.; Becofsky, K.; Weiss, R.; Das, S.K. Dietary Intake and Physical Activity Assessment: Current Tools, Techniques, and Technologies for Use in Adult Populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, e93–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Hoover, A.; Scisco, J.; Muth, E. A new method for measuring meal intake in humans via automated wrist motion tracking. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2012, 37, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Päßler, S.; Wolff, M.; Fischer, W.J. Food intake monitoring: An acoustical approach to automated food intake activity detection and classification of consumed food. Physiol. Meas. 2012, 33, 1073–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.K.; Cho, B.; Kwon, H.; Son, K.Y.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.K.; Park, J. A Mobile-Based Comprehensive Weight Reduction Program for the Workplace (Health-On): Development and Pilot Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e11158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmenter, K.; Wardle, J. Development of a general nutrition knowledge questionnaire for adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, J.; Larsen, M.E.; Proudfoot, J.; Christensen, H. Mobile Apps for Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review of Features and Content Quality. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShazo, J.; Harris, L.; Turner, A.; Pratt, W. Designing and remotely testing mobile diabetes video games. J. Telemed. Telecare 2010, 16, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Direito, A.; Jiang, Y.; Whittaker, R.; Maddison, R. Apps for IMproving FITness and Increasing Physical Activity Among Young People: The AIMFIT Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelnuovo, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Pietrabissa, G.; Corti, S.; Giusti, E.M.; Molinari, E.; Simpson, S. Obesity and outpatient rehabilitation using mobile technologies: The potential mHealth approach. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author, Publication Year | Document Type | Designs of Studies Included in the Review | Country of Author | Age Group (Age Range)—Special Populations | Date Range of the Search | N. of Databases Searched | Overall Review Aim | Outcomes | Type of Tools | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mateo, G.F., 2015 | SR a, MA b | RCTs c | Spain | Adults (age range not specified) | 1960–2015 | 3 | Health promotion, weight loss interventions | Body weight, BMI d, waist circumference | Mobile app | [14] |

| Semper, H.M., 2016 | SR, MA | Quasi-experimental RCTs and RCTs | UK | Adult (>18 ages) | 2014 (May)–2015 (April) | 16 | Health promotion, weight loss interventions | Weight loss | Mobile app | [15] |

| Schoeppe, S., 2016 | SR | RCTs | Australia | Adults and children (age range not specified) | 2006–2016 | 5 | Health promotion | Diet, weight loss, BMI, daily fruit and vegetable intake, physical activity and sedentary behavior, blood pressure | Mobile app, messaging tools (text or audio messages), website, pedometer | [16] |

| Füzéki, E., 2017 | SR | Cross-sectional and longitudinal study | Germany | Adults and older adults (≥18 ages) | 2007–2016 (March) | 4 | Summarize available evidence on the relationship between e LIPA and health outcomes measurable through wearable devices | Obesity, mortality, markers of lipid and glucose metabolism | Wearable motion sensors (accelerometers) | [17] |

| Heesch, K.C., 2018 | SR | Descriptive studies, validation studies, review | Australia | Adults (age ≥60 years) | 2017 (December)–2018 (November) | 3 | Assess the validity and reliability of accelerometers for the assessment of sedentary behavior | Sedentary behavior, older adults | Wearable motion sensors (accelerometers) | [18] |

| Lee, M., 2018 | SR | RCTs | Korea | Adults (<35 years) | 1937–2017 (November) | 3 | Health promotion | Nutrition knowledge, diet quality, body weight, BMI | Mobile App, website, personal coaching, SMS, pedometer | [19] |

| Maddison, R., 2019 | SR | Feasibility, pilot, validation and methodological studies, RCTs | Australia | Adults, school students, older adults (age range not specified) | 2010–2017 | 9 | Use of wearable cameras to capture health-related behaviors | Self-management, dietary intake, physical activity, activities of daily living, sedentary behavior | Wearable cameras | [8] |

| Mandracchia, F., 2019 | SR | RCTs | Spain | 16–71 years | 2008–2018 | 2 | Health promotion | Dietary habits, healthy weight and healthy body fat percentage, f PA | Mobile App, text and/or audio messages, coaching, emails, accelerometer | [7] |

| Villinger, K., 2019 | SR, MA | RCTs | Germany | Adolescent and adults (age range not specified) | 2006–2017 | 7 | Health promotion, nutrition-related health outcomes | Body weight, BMI, clinical parameters (blood lipids) | Mobile app and text messages | [6] |

| Zarnowiecki, D., 2020 | SR | RCTs, cohort and cross-sectional and qualitative studies | Australia | Intervention aimed at parents of children (age range not specified) | 2013–2018 | 5 | Nutrition promotion | Healthy food consumption (fruit and vegetable) | Mobile app and website | [20] |

| Paramastri, R., 2020 | SR | RCTs, nested trial, case–control trial, pilot RCT | Taiwan, Pakistan, Qatar, Canada | >18 ages | 2010–2018 | 4 | Increase knowledge related to nutrition | Vegetable and sugar-sweetened beverages intake, body composition (fat mass, weight, body mass index), diet behaviors, PA | Mobile apps, coaching calls, text messages, website | [21] |

| Hall, K.S., 2020 | SR | Prospective studies | U.S.A. | Adults (≥18 ages) | 1937–2019 (August) | 4 | Identify daily steps number and evaluate their association with all-cause mortality, g CVD morbidity or mortality, and dysglycemia | Daily step count | Wearable devices (pedometer and accelerometer) | [22] |

| Cavero-Redondo, I., 2020 | SR, MA | RCTs, non-RCTs, pilot studies | Spain | Adults (20–60 year) | 1900–2020 | 4 | Behavioral weight management interventions | Body weight | Mobile App, Website | [23] |

| McDonough, D.J., 2021 | SR, MA | RCT | U.S.A. | Adults (age range not specified) | 2019 (December)–2020 (September) | 6 | Incorporate wearable technologies into physical activity interventions to reduce body weight and BMI | Body weight, BMI, step count | Wearable devices (accelerometer, pedometer) | [24] |

| Dixit, S., 2021 | Review | RCTs, SR, MA | Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | All ages (age range not specified) | 2014–2020 | 3 | Explore the possible role of technological advances and social media platforms as an alternative tool in promoting a healthy living style | Physical activity, dietary intervention | Websites, webpages, wikis, mobile devices and apps, social media and social networking channels, video chat, video sharing, podcast media wearable devices, training devices | [4] |

| Robert, C., 2021 | SR, MA | RCTs | Singapore | ≥40 years | 2014–2019 | 5 | Improve diet and nutrition | Anthropometric measures, clinical outcomes, PA, smoking cessation, medication adherence, behavioral change techniques | Mobile apps, wearable technology, web-based app, phone calls, email, text messages, video-conferencing, tele-health sessions | [25] |

| Davies, A., 2021 | SR | Primary studies, SRs, review | Australia | 13–35 years | 2008 (January)–2021 | 7 | Validity of new technologies that measure bone-related dietary and physical activity risk factors in adolescents and young adults | Diet and physical activity | Wearable cameras, body-worn monitors, accelerometers online web-based tools, mobile-based tools or apps | [26] |

| Raber, M., 2021 | SR | RCT, experimental and longitudinal | USA | Adults (>20 years) | 1937–2020 | 8 | Health promotion (weight loss interventions) | Weight loss | Mobile apps, paper food diaries, wearables, websites and personal digital assistants | [27] |

| Chevance, G., 2022 | SR, MA | SRs, MAs, comparative study, validation study | Spain | Adult (>18 years) | 2015 (January)– 2021 (July) | 2 | Validation of wearable devices as tools used for health outcomes | Heart rate, energy expenditure, step count | Wearable device | [28] |

| Scarry, A., 2022 | SR | RCTs, short report, pilot study | Ireland | Adult (>18 ages) | 2010–2020 | 3 | Diet quality improvement | Quality diet, weight loss, diet management, h HbA1c control, sodium intake, BMI, blood pressure, hemoglobin, i FPG, and serum lipids | Mobile apps, wearable devices, SMS, email, social networking apps, websites, personal online coaching | [29] |

| Ferguson, T., 2022 | SR | SR, MA | Australia | All ages (age range not specified) | 1900–2021 (April) | 7 | Examine the effectiveness of activity trackers for improving physical activity, physiological and psychosocial outcomes | Step count, energy expenditure, walking, aerobic capacity, j VO2max, psychosocial outcomes | Wearable activity tracker: pedometer, accelerometer, activity monitor, and step-counting smartphone application | [30] |

| Chew, H.S.J., 2022 | SR, MA | RCTs | Singapore | Adults (22–70 years) | 1900–2022 | 7 | Health promotion | Weight loss, waist circumference (cm), calorie intake, blood pressure, k HDL-C, l LDL-C, HbA1C | Mobile apps, personalized messages, coaching, step tracker | [31] |

| Eppes, E.V., 2023 | SR | RCTs, pre-post studies, pilot studies, feasibility study, prospective cohort study, descriptive study, cross-sectional study | USA | Parents of young children and adolescents (age range not specified) | 2009–2022 | 5 | Health promotion | m FV consumption, healthy diet, healthy weight | Mobile apps, messaging tools, app and wearable device | [32] |

| De Santis, K.K., 2023 | SR | Primary study, SR, RCT, Non-randomized studies | Germany | 50–99 years | 2005–2022 (June) | 4 | Health promotion and disease prevention | Health promotion, mobility, mental health, nutrition, or cognition | Website, text-message, email, app, exergaming, mobile phone | [33] |

| Chew, H.S.J., 2023 | SR, MA | RCTs | Singapore | Adults (>18 years) | 1900–2022 | 7 | Health promotion and weight loss intervention | Weight loss | Mobile apps and coaching | [34] |

| Giurgiu, M., 2023 | SR, MA | Validation studies | Germany | ≥18 years | 1970–2020 (December) | 5 | Evaluation of the characteristics, validity, and quality of wearable devices used for 24 h for the measurement of anamnestic parameters | Sleep patterns, postures, sedentary behavior, physical activity, energy expenditure, steps count | Wearable device: wearing position, software, epoch-length, algorithm/cut-point | [35] |

| Shoneye, C.L., 2023 | SR | RCTs | Australia | ≥18 years | 1990–2020 | 5 | Diet quality | Dietary feedback, tailored weight-loss interventions, digital weight loss intervention | Mobile app, website, accelerometer, computer software, text message | [36] |

| Authors, Year (Reference) | 1. PICO | 2. Review Methods * | 3. Study Selection | 4. Search Strategy * | 5. Study Selection | 6. Data Extraction | 7. Excluded Studies * | 8. Describe Studies | 9. ROB Tool * | 10. Report Funding | 11. Statistical Methods * | 12. ROB Assessment | 13. ROB Discussion * | 14. Study Differences | 15. Pubblication Bias * | 16. COI and Funding | AMSTAR 2 Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mateo, G.F. et al., 2015 [14] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Semper H.M. et al., 2016 [15] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | No | Low |

| Schoeppe S. et al., 2016 [16] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | No | No | N/A | N/A | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | Critically Low |

| Füzéki E et al., 2017 [17] | Yes | Partial Yes | No | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial Yes | No | No | N/A | N/A | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | Critically Low |

| Heesch K.C. et al., 2018 [18] | No | Partial Yes | No | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial Yes | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Low |

| Lee M. et al., 2018 [19] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Low |

| Maddison R. et al., 2019 [8] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | No | N/A | Yes | Low |

| Mandracchia F. et al., 2019 [7] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Low |

| Villinger K. et al., 2019 [6] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Zarnowiecki D. et al., 2020 [20] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | No | No | Partial Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Critically Low |

| Paramastri R. et al., 2020 [21] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial Yes | No | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | Critically Low |

| Hall K.S. et al., 2020 [22] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial Yes | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | Critically Low |

| Cavero-Redondo I. et al., 2020 [23] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| McDonough D.J. et al., 2021 [24] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Dixit S. et al., 2021 [4] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Critically Low |

| Robert C. et al., 2021 [25] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Davies A. et al., 2021 [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | Low |

| Raber M. et al., 2021 [27] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Low |

| Chevance G. et al., 2022 [28] | Yes | Partial Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Scarry A. et al., 2022 [29] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Low |

| Ferguson T. et al., 2022 [30] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Chew H.S.J. et al., 2022 [31] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Eppes E.V. et al., 2023 [32] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Low |

| De Santis K.K. et al., 2023 [33] | No | No | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial Yes | No | Yes | N/A | N/A | No | Yes | N/A | Yes | Critically Low |

| Chew H.S.J. et al., 2023 [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | Partial Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Giurgiu M. et al., 2023 [35] | Yes | Partial Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partial Yes | Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Moderate |

| Shoneye C.L. et al., 2023 [36] | Yes | Partial Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Partial Yes | No | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Critically Low |

| Responses by Domain | 1. | 2. * | 3. | 4. * | 5. | 6. | 7. * | 8. | 9. * | 10. | 11. * | 12. | 13. * | 14. | 15. * | 16. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 25 | 4 | 23 | 3 | 26 | 26 | 17 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 19 | 21 | 9 | 26 |

| Partial Yes | 0 | 22 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 24 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 11 | 20 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giardina, M.; Zarcone, R.; Accardi, G.; Tabacchi, G.; Bellafiore, M.; Terzo, S.; Di Liberto, V.; Frinchi, M.; Boffetta, P.; Mazzucco, W.; et al. Empowering Health Through Digital Lifelong Prevention: An Umbrella Review of Apps and Wearables for Nutritional Management. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3542. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223542

Giardina M, Zarcone R, Accardi G, Tabacchi G, Bellafiore M, Terzo S, Di Liberto V, Frinchi M, Boffetta P, Mazzucco W, et al. Empowering Health Through Digital Lifelong Prevention: An Umbrella Review of Apps and Wearables for Nutritional Management. Nutrients. 2025; 17(22):3542. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223542

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiardina, Marta, Rosa Zarcone, Giulia Accardi, Garden Tabacchi, Marianna Bellafiore, Simona Terzo, Valentina Di Liberto, Monica Frinchi, Paolo Boffetta, Walter Mazzucco, and et al. 2025. "Empowering Health Through Digital Lifelong Prevention: An Umbrella Review of Apps and Wearables for Nutritional Management" Nutrients 17, no. 22: 3542. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223542

APA StyleGiardina, M., Zarcone, R., Accardi, G., Tabacchi, G., Bellafiore, M., Terzo, S., Di Liberto, V., Frinchi, M., Boffetta, P., Mazzucco, W., Scordino, M., Vasto, S., & Amato, A. (2025). Empowering Health Through Digital Lifelong Prevention: An Umbrella Review of Apps and Wearables for Nutritional Management. Nutrients, 17(22), 3542. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17223542