Impact of Family Involvement in Cardiac Rehabilitation—Insights from a Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

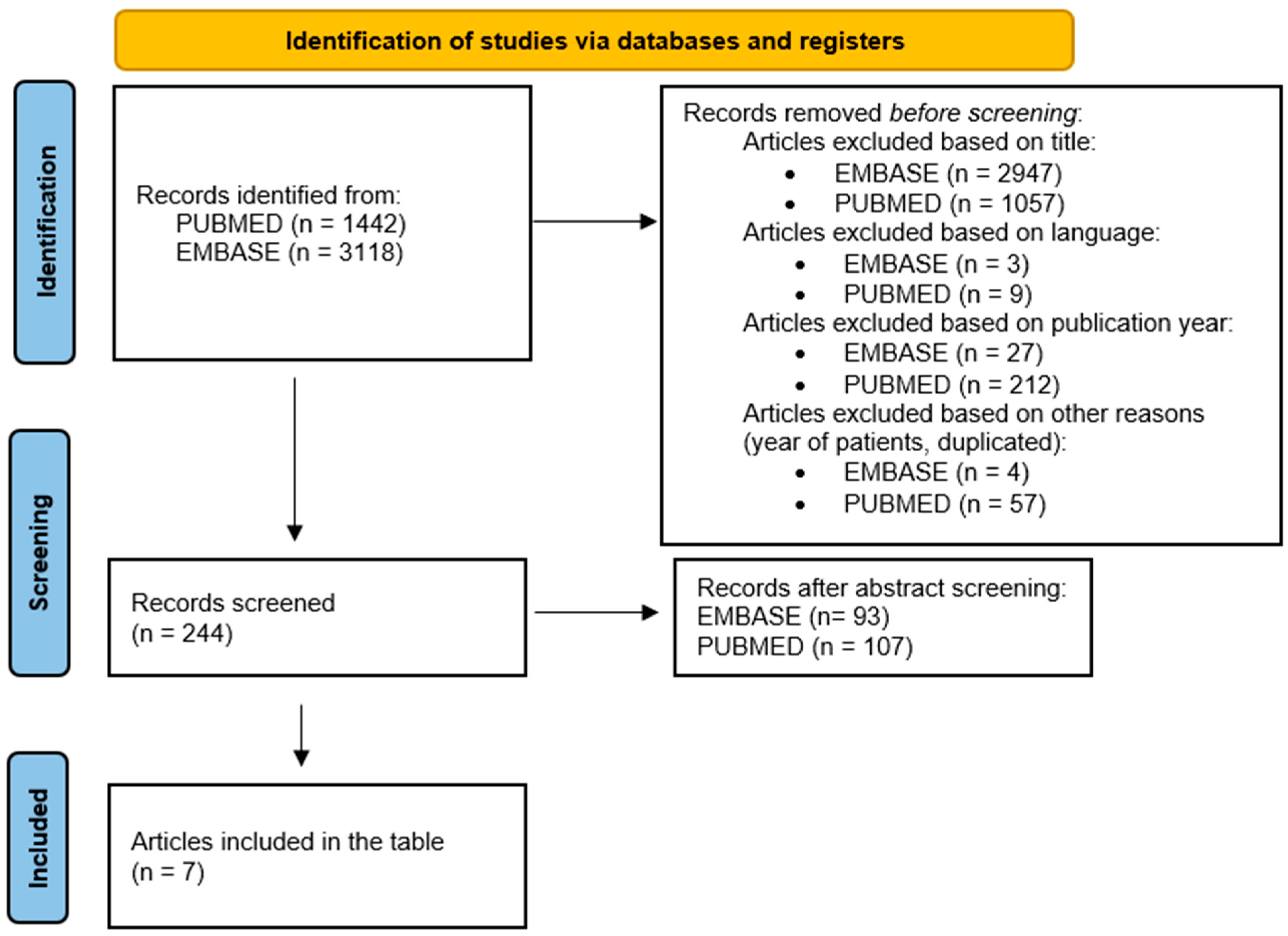

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Does Family Support Matter in the Cardiovascular Recovery Process?

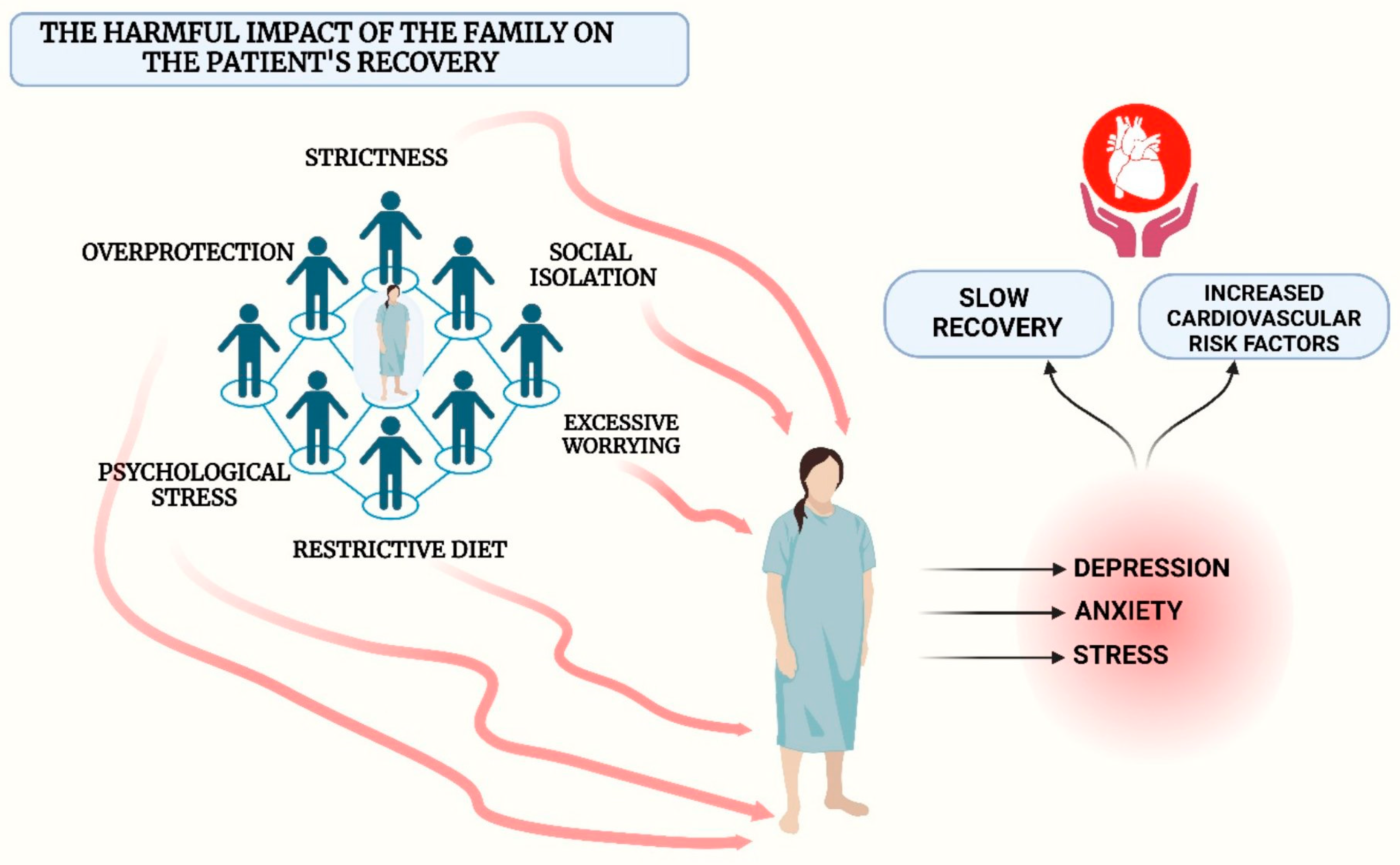

4.2. Does Family Involvement Negatively Impact Cardiovascular Recovery?

4.3. Does Involvement in Cardiovascular Rehabilitation Affect the Family?

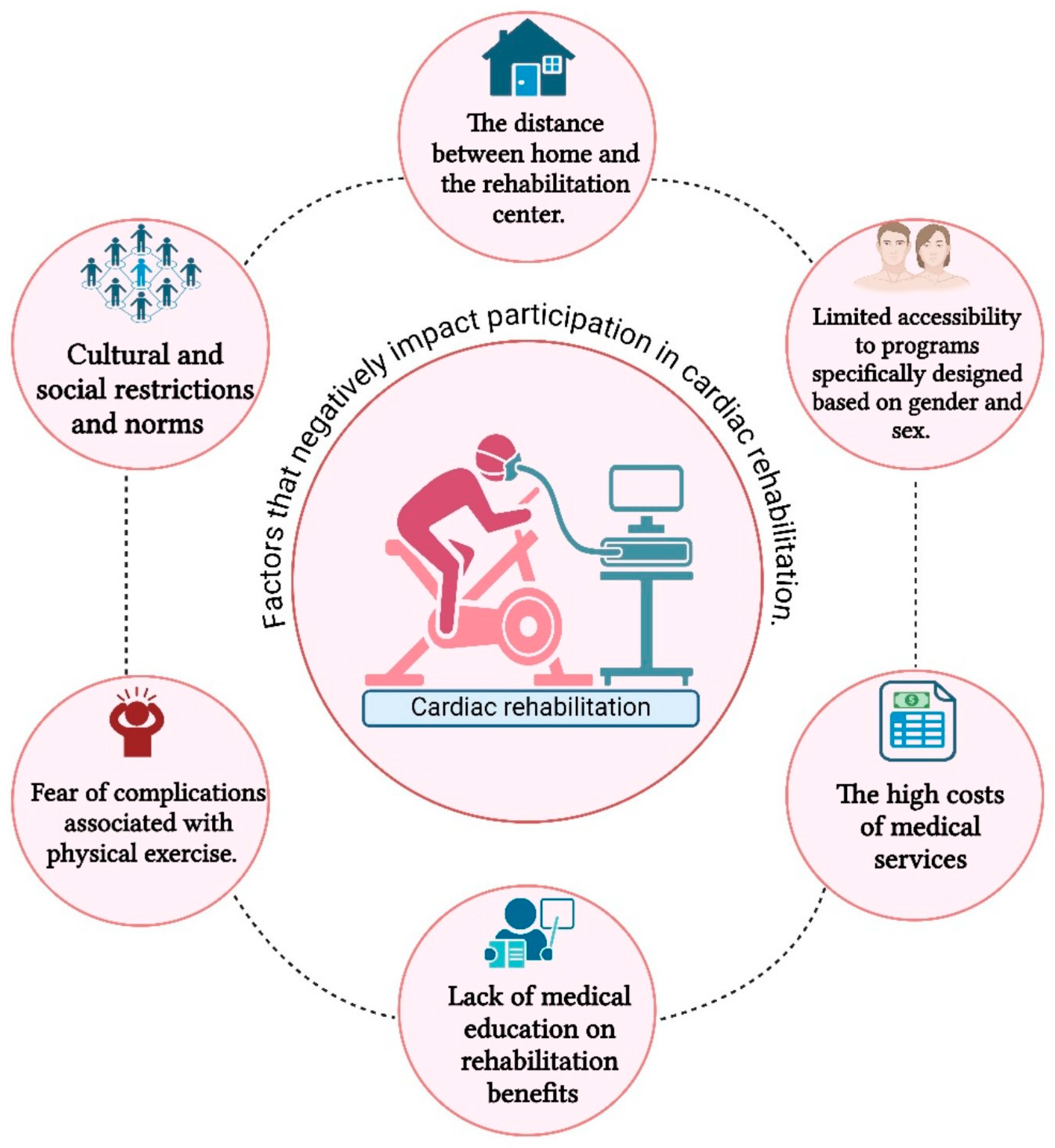

4.4. Socio-Economic Factors That Impact Cardiac Rehabilitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Patel, L.; Dhruve, R.; Keshvani, N.; Pandey, A. Role of exercise therapy and cardiac rehabilitation in heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 82, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balady, G.J.; Williams, M.A.; Ades, P.A.; Bittner, V.; Comoss, P.; Foody, J.M.; Franklin, B.; Sanderson, B.; Southard, D.; American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee, the Council on Clinical Cardiology; et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association exercise, cardiac rehabilitation, and prevention committee, the council on clinical cardiology; the councils on cardiovascular nursing, epidemiology and prevention, and nutrition, physical activity, and metabolism; and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation 2007, 115, 2675–2682. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiev, A.; Terziev, A.; Gotcheva, N. Effects of an Early Cardiac Rehabilitation Following Heart Surgery in Patients over 70 Years. SM J. Clin. Med. 2017, 3, 1019. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.; Yu, H.; Xie, F.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Shao, B.; Liu, J.; et al. Effects of early rehabilitation on functional outcomes in patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J. Int. Med. Res. 2022, 50, 3000605221087031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbara, B.; Lin, T.; Greissinger, K.; Rottner, L.; Rillig, A.; Zimmerling, S. The Beneficial Effects of Cardiac Rehabilitation. Adis J. 2020, 9, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurst, R.; Kinkel, S.; Lin, J.; Goehner, W.; Fuchs, R. Promoting physical activity through a psychological group intervention in cardiac rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. J. Behav. Med. 2019, 42, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosetti, M.; Abreu, A.; Corrà, U.; Davos, C.H.; Hansen, D.; Frederix, I.; Ilious, M.C.; Pedretti, R.F.E.; Schmid, J.-P.; Vigorito, C.; et al. Secondary prevention through comprehensive cardiovascular rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. 2020 update. A position paper from the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 460–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffey, A.E.; Goldstein, C.M.; Hays, M.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Gaalema, D.E. Psychological Risk Factors in Cardiac Rehabilitation: Anxiety; Depression; Social Isolation; and Anger/Hostility. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2023, 43, E20–E21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewska, K.; Radecki, K.; Cieślik, B. Does Psychological State Influence the Physiological Response to Cardiac Rehabilitation in Older Adults? Medicina 2024, 60, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Zecchin, R.; Newton, P.J.; Phillips, J.L.; DiGiacomo, M.; Denniss, A.R.; Hickman, L.D. The prevalence and impact of depression and anxiety in cardiac rehabilitation: A longitudinal cohort study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, L.C.; Kasl, S.V.; Lichtman, J.; Vaccarino, V.; Krumholz, H.M. Social support and change in health-related quality of life 6 months after coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Psychosom. Res. 2006, 60, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astin, F.; Atkin, K.; Darr, A. Family Support and Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Comparative Study of the Experiences of South Asian and White-European Patients and Their Carer’s Living in the United Kingdom. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008, 7, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Sanjari, M.J.; Rahimi-Bashar, F.; Gohari-Mogadam, K.; Ouahrani, A.; Mustafa, E.M.M.; Hssain, A.A.; Sahebkar, A. Cardiac Rehabilitation Using the Family-Centered Empowerment Model is Effective in Improving Long-term Mortality in Patients with Myocardial Infarction: A 10-year Follow-Up Randomized Clinical Trial. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2024, 31, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Song, H. Clinical Effects of Hospital–Family Collaborative Cardiac Rehabilitation Training on Patients With Heart Failure After Cardiac Valve Prostheses. HSF 2024, 27, E1175–E1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtwistle, S.B.; Jones, I.; Murphy, R.; Gee, I.; Watson, P.M. Family support for physical activity post-myocardial infarction: A qualitative study exploring the perceptions of cardiac rehabilitation practitioners. Nurs. Health Sci. 2021, 23, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-C.; Lou, S.-N.; Zhu, X.-L.; Zhang, R.-L.; Wu, L.; Xu, J.; Ding, X.-J.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y. Needs and Constraints for Cardiac Rehabilitation Among Patients with Coronary Heart Disease Within a Community-Based Setting: A Study Based on Focus Group Interviews. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2024, 18, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, S.; Koivula, M.; Åstedt-Kurki, P.; Helminen, M. Family involvement in rehabilitation: Coronary artery disease-patients’ perspectives. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 3020–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagan, N.A.; Botti, M.A.; Watts, R.J. Financial, family, and social factors impacting on cardiac rehabilitation attendance. Heart Lung 2007, 36, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laidsaar-Powell, R.C.; Butow, P.N.; Bu, S.; Charles, C.; Gafni, A.; Lam, W.W.; Jansen, J.; McCaffery, K.J.; Shepherd, H.L.; Tattersall, M.H.; et al. Physician-patient-companion communication and decision-making: A systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 91, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, D.; Laidsaar-Powell, R.; Tilden, W.; Latt, M.; Butow, P. Health care providers’ perceptions of family caregivers’ involvement in consultations within a geriatric hospital setting. Geriatr. Nurs. 2018, 39, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.M.; King-Shier, K.M.; Spaling, M.A.; Duncan, A.S.; Stone, J.A.; Jaglal, S.B.; Thompson, D.R.; Angus, J.E. Factors influencing participation in cardiac rehabilitation programmes after referral and initial attendance: Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Clin. Rehabil. 2013, 27, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsén, P.; Brink, E.; Persson, L.O. Patients’ illness perception four months after a myocardial infarction. J. Clin. Nurs. 2008, 17, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Miller, A.C.; Hajiesmaieli, M.; Kangasniemi, M.; Alhani, F.; Jelvehmoghaddam, H.; Fathi, M.; Farzanegan, B.; Ardehali, S.H.; Hatamian, S.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation using the Family Centered Empowerment Model versus home-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with myocardial infarction:a randomised controlled trial. Open Heart 2016, 3, e000349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocanda, L.; Schumacher, T.L.; Plotnikoff, R.C.; Whatnall, M.C.; Fenwick, M.; Brown, L.J.; Rollo, M.E.; Jansson, A.; Burrows, T.L.; Duncan, M.J.; et al. Effectiveness and reporting of nutrition interventions in cardiac rehabilitation programmes: A systematic review. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2023, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, S.A.; Schumacher, K.L.; Leinen, D.D.; Phillips, B.G.; Schulz, P.S.; Yates, B.C. Couples’ Experiences with Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors After Cardiac Rehabilitation. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2018, 38, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borah, N.; Bhawalkar, J.S.; Rathod, H.; Jadav, V.; Gangurde, S.; Johnson, S. Challenges to Cardiac Rehabilitation Post Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: A Qualitative Study in Pune. Cureus 2023, 15, e35755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Farrell, P.; Murray, J.; Hotz, S.B. Psychologic distress among spouses of patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation. Heart Lung 2000, 29, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quit Smoking & Vaping: Get Expert Cessation Tips & Help Quit. Available online: https://www.quit.org.au/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- NHK.UK. Quit smoking—Better Health. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/better-health/quit-smoking/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.-b). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/quit-smoking/index.html/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- United States Government. National Insitute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Aliat, O.N.G. ALIAT-Asociatia Aliat Pentru Sanatate Mintala, (.2.0.2.4.; 30 June). Available online: https://aliat-ong.ro/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Ministerul Sănătății. (n.d.-b). Available online: https://www.ms.ro/ro (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- More Countries Using Health Taxes and Laws to Protect Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/accountability/results/who-results-report-2022-mtr/more-countries-using-health-taxes-and-laws-to-protect-health (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Tobacconomics. Tobacco Tax Increases Around the World—August 2023 Update. (15 August 2023). Available online: https://www.tobacconomics.org/blog/tobacco-tax-increases-around-the-world-august-2023-update/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Van Horn, E.; Fleury, J.; Moore, S. Family interventions during the trajectory of recovery from cardiac event: An integrative literature review. Heart Lung 2002, 31, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, G.; Molloy, G.J.; Steptoe, A. The impact of an acute cardiac event on the partners of patients: A systematic review. Health Psychol. Rev. 2009, 3, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano-Ravina, A.; Pena-Gil, C.; Abu-Assi, E.; Raposeiras, S.; van ‘t Hof, A.; Meindersma, E.; Bossano Prescott, E.I.; González-Juanatey, J.R. Participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs. A systematic review. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 223, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.S.; Davidson, P.; Griffiths, R. Cardiac rehabilitation coordinators’ perceptions of patient-related barriers to implementing cardiac evidence-based guidelines. J Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008, 23, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Eberhardt, J.; van Wersch, A.; Ling, J. Cultural influences on adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programmes: Perspectives from South Asian healthcare professionals. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2022, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carew Tofani, A.; Taylor, E.; Pritchard, I.; Jackson, J.; Xu, A.; Kotera, Y. Ethnic Minorities’ Experiences of Cardiac Rehabilitation:A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, G.L.; dos Santos, R.Z.; Aranha, E.E.; Nunes, A.D.; Oh, P.; Benetti, M.; Grace, S.L. Perceptions of barriers to cardiac rehabilitation use in Brazil. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2013, 9, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhillips, R.; Capobianco, L.; Cooper, B.G.; Husain, Z.; Wells, A. Cardiac rehabilitation patients experiences and understanding of group metacognitive therapy: A qualitative study. Open Heart 2021, 8, e001708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Engen-Verheul, M.; de Vries, H.; Kemps, H.; Kraaijenhagen, R.; de Keizer, N.; Peek, N. Cardiac rehabilitation uptake and its determinants in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2013, 20, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishram, S.; Crosland, A.; Unsworth, J.; Long, S. Engaging women from South Asian communities in cardiac rehabilitation. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2007, 12, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, U.; Baker, D.; Lester, H.; Edwards, R. Exploring uptake of cardiac rehabilitation in a minority ethnic population in England: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2010, 9, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cersosimo, A.; Longo Elia, R.; Condello, F.; Colombo, F.; Pierucci, N.; Arabia, G.; Matteucci, A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Vizzardi, E.; et al. Cardiac rehabilitation in patients with atrial fibrillation. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2025, 73, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Mei, Z.; Yang, L.; Yan, C.; Han, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Hybrid Comprehensive Telerehabilitation (HCTR) for Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Occup. Ther. Int. 2023, 2023, 5147805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghisi, G.L.M. Transforming patient education in cardiac rehabilitation: A vision for the future. Patient Educ. Couns. 2025, 138, 109176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veloso, A.; Rocha, R.; Macedo, G.; Teixeira, A.; Almeida, V. Cardiovascular Rehabilitation: Perspectives of patients and healthcare professionals on the implementation of multidisciplinary programs. Sci. Lett. 2025, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year, Author and Country | Name of the Article | Number of Participants | Sex and Age of Participants | Patient’s Diagnostic | Study Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vahedian-Azimi et al., 2024, Iran [13] | Cardiac Rehabilitation Using the Family-Centered Empowerment Model is Effective in Improving Long-term Mortality in Patients with Myocardial Infarction: A 10-year Follow-Up Randomized Clinical Trial | 70 patients | 61.40 ± 12.83 Years, 65.7% males. | Myocardial infarction | Randomized Clinical Trial |

| Zhang et al., 2024, China [14] | Clinical Effects of Hospital-Family Collaborative Cardiac Rehabilitation Training on Patients with Heart Failure after Cardiac Valve Prostheses | 201 patients | Mean age 67 years, 61% males. | Heart failure | Retrospective study |

| Birtwistle et al., 2020, UK [15] | Family support for physical activity post-myocardial infarction: A qualitative study exploring the perceptions of cardiac rehabilitation practitioners | 14 cardiac rehabilitation practitioners | No data available | Myocardial infarction | A qualitative study |

| Ma et al., 2024, China [16] | Needs and Constraints for Cardiac Rehabilitation Among Patients with Coronary Heart Disease Within a Community-Based Setting: A Study Based on Focus Group Interviews | 11 patients | 55–80 years, 72.72% females | Coronary heart disease | Semi-structured interview |

| Tuomisto et al., 2018, Finland [17] | Family Involvement in Rehabilitation: Coronary Artery Disease–patients’ perspectives | 169 patients | 61–74 years, 76% males | Coronary artery disease | Descriptive cross-sectional study |

| Hagan et al., 2007, Australia [18] | Financial, family, and social factors impacting on cardiac rehabilitation attendance | 10 patients | 43–82 years, 80% males | Myocardial infarction | Semi-structured interview |

| Astin et al., 2008, UK [12] | Family support and cardiac rehabilitation: A comparative study of the experiences of South Asian and White-European patients and their carers living in the United Kingdom | 65 patients | 40–83 years, 55.38% males | Angina (32%), Myocardial infarction (42%), CABG surgery | Semi-structured interviews |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popescu, G.; Maștaleru, A.; Oancea, A.; Costache, A.-D.; Adam, C.A.; Rîpă, C.; Cumpăt, C.M.; Leon, M.M. Impact of Family Involvement in Cardiac Rehabilitation—Insights from a Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186468

Popescu G, Maștaleru A, Oancea A, Costache A-D, Adam CA, Rîpă C, Cumpăt CM, Leon MM. Impact of Family Involvement in Cardiac Rehabilitation—Insights from a Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(18):6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186468

Chicago/Turabian StylePopescu, Gabriela, Alexandra Maștaleru, Andra Oancea, Alexandru-Dan Costache, Cristina Andreea Adam, Carmen Rîpă, Carmen Marinela Cumpăt, and Maria Magdalena Leon. 2025. "Impact of Family Involvement in Cardiac Rehabilitation—Insights from a Literature Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 18: 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186468

APA StylePopescu, G., Maștaleru, A., Oancea, A., Costache, A.-D., Adam, C. A., Rîpă, C., Cumpăt, C. M., & Leon, M. M. (2025). Impact of Family Involvement in Cardiac Rehabilitation—Insights from a Literature Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(18), 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14186468