Advancing Nanotoxicology: High-Throughput Screening for Assessing the Toxicity of Nanoparticle Mixtures †

Abstract

1. Introduction

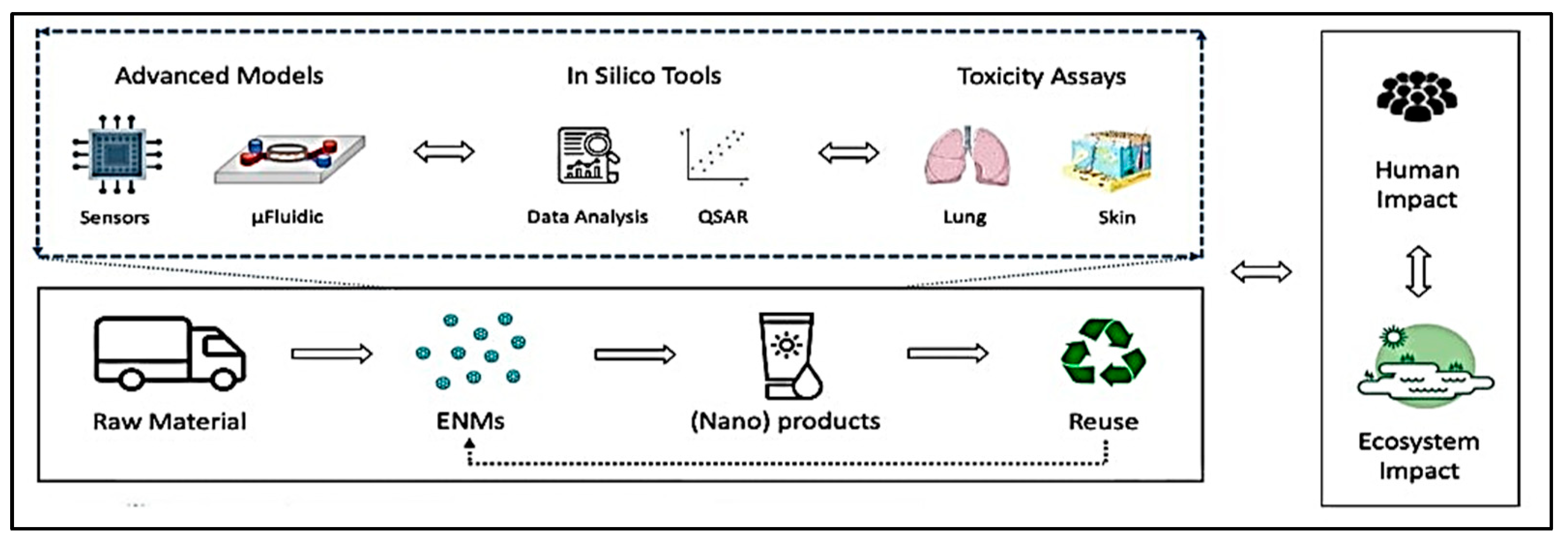

2. Traditional and Modern Toxicological Studies

3. Advanced Risk Assessment by HTS

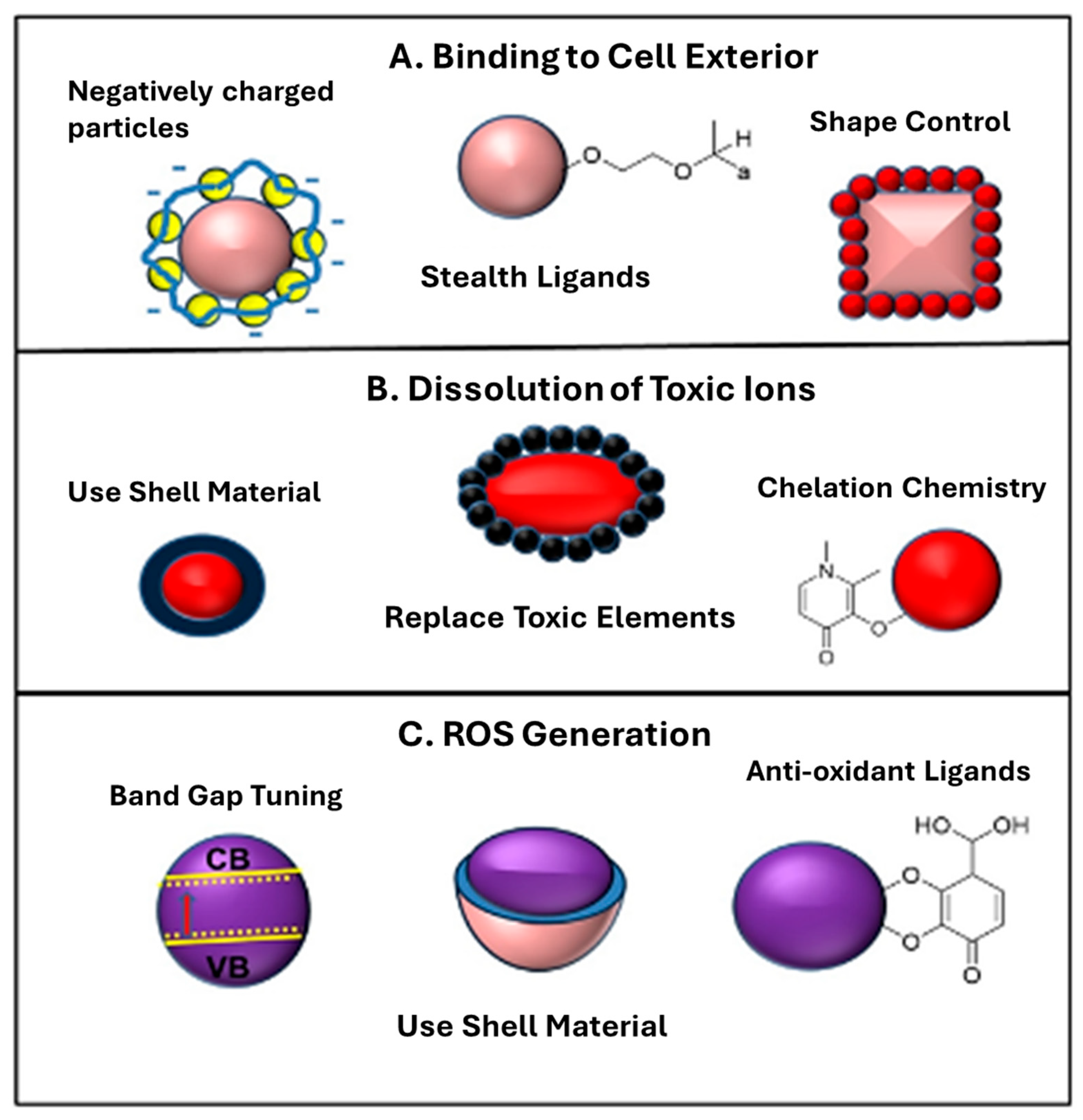

4. Oxidative Stress and Effects of Metal Ion Interaction

5. Predictive Modeling for Safer NP Use

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikam, A.P.; Ratnaparkhiand, M.P.; Chaudhari, S.P. Nanoparticles—An Overview. Int. J. Res. Dev. Pharm. Life Sci. 2014, 3, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, T.; Kovochich, M.; Nel, A. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species and Oxidative Stress in Mediating Particulate Matter Injury. Clin. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 5, 817–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, M.-S.; Jegal, H.; Heo, M.B.; Kwak, M.; Shon, H.K.; Song, S.; Lee, T.G.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, D.W.; et al. New Approach Methodologies for in Vitro Toxicity Screening of Nanomaterial Using a Pulmonary Three-Dimensional Floating Extracellular Matrix Model. J. Biol. Eng. 2025, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliu, N.; Fadeel, B. Nanotoxicology: No Small Matter. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaesser, A.; Howard, C.V. Toxicology of Nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozman, K.K.; Doull, J. Paracelsus, Haber and Arndt. Toxicology 2001, 160, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Chen, L.; Zhou, H.; Fourches, D.; Tropsha, A.; Yan, B. Chemical basis of interactions between engineered nanoparticles and biological systems. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 7740–7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Huan, Y.; Zhao, J.X.; Wu, M.; Kannan, S. Toxicity of Nanomaterials to Living Cells. Proc. North Dak. Acad. Sci. 2005, 59, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Nel, A.; Xia, T.; Mädler, L.; Li, N. Toxic Potential of Materials at the Nanolevel. Science 2006, 311, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, V.L. The Potential Environmental Impact of Engineered Nanomaterials. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1166–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberdörster, G.; Oberdörster, E.; Oberdörster, J. Nanotoxicology: An Emerging Discipline Evolving from Studies of Ultrafine Particles. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, K.; Stone, V.; Tran, C.L.; Kreyling, W.; Borm, P.J.A. Nanotoxicology. Occup. Environ. Med. 2004, 61, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhawan, A.; Sharma, V.; Parmar, D. Nanomaterials: A Challenge for Toxicologists. Nanotoxicology 2009, 3, 5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelikar, U.; Ghorpade, K.B.; Kumar, A.; Patel, A.; Singh, M.; Banjare, N.; Gupta, P.N. Comprehensive Insights into Mechanism of Nanotoxicity, Assessment Methods and Regulatory Challenges of Nanomedicines. Discover Nano 2024, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatkin, J.A.; Ong, K.J.; Beaudrie, C.; Clippinger, A.J.; Hendren, C.O.; Haber, L.T.; Hill, M.; Holden, P.; Kennedy, A.J.; Kim, B.; et al. Advancing Risk Analysis for Nanoscale Materials: Report from an International Workshop on the Role of Alternative Testing Strategies for Advancement. Risk Anal. 2016, 36, 1520–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damoiseaux, R.; George, S.; Li, M.; Pokhrel, S.; Ji, Z.; France, B.; Xia, T.; Suarez, E.; Rallo, R.; Mädler, L.; et al. No Time to Lose—High Throughput Screening to Assess Nanomaterial Safety. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Pokhrel, S.; Xia, T.; Gilbert, B.; Ji, Z.; Schowalter, M.; Rosenauer, A.; Damoiseaux, R.; Bradley, K.A.; Mädler, L.; et al. Use of a Rapid Cytotoxicity Screening Approach To Engineer a Safer Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle through Iron Doping. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usenko, C.Y.; Harper, S.L.; Tanguay, R.L. In Vivo Evaluation of Carbon Fullerene Toxicity Using Embryonic Zebrafish. Carbon 2007, 45, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfuhler, S.; Downs, T.R.; Allemang, A.J.; Shan, Y.; Crosby, M.E. Weak Silica Nanomaterial-Induced Genotoxicity Can Be Explained by Indirect DNA Damage as Shown by the OGG1-Modified Comet Assay and Genomic Analysis. Mutagenesis 2017, 32, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavlock, R.J.; Austin, C.P.; Tice, R.R. Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: Implications for Human Health Risk Assessment. Risk Anal. 2009, 29, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Hao, M.; Phalen, R.F.; Hinds, W.C.; Nel, A.E. Particulate Air Pollutants and Asthma: A Paradigm for the Role of Oxidative Stress in PM-Induced Adverse Health Effects. Clin. Immunol. 2003, 109, 250–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xia, T.; Nel, A.E. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Ambient Particulate Matter-Induced Lung Diseases and Its Implications in the Toxicity of Engineered Nanoparticles. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 1689–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, D.J.; La Du, J.; Thunga, P.; Elson, D.; Truong, L.; Kolluri, S.K.; Tanguay, R.L.; Reif, D.M. Leveraging a High-Throughput Screening Method to Identify Mechanisms of Individual Susceptibility Differences in a Genetically Diverse Zebrafish Model. Front. Toxicol. 2022, 4, 846221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flandrois, J.-P.; Lina, G.; Dumitrescu, O. MUBII-TB-DB: A Database of Mutations Associated with Antibiotic Resistance in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, A.Z.; Xie, S.; Li, X.; Cen, T.; Li, D.; Chen, J. Nano-Metal Oxides Induce Antimicrobial Resistance via Radical-Mediated Mutagenesis. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.N.; Yoon, T.J.; Minai-Tehrani, A.; Kim, J.E.; Park, S.J.; Jeong, M.S.; Ha, S.W.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, J.S.; Cho, M.H. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Induced Autophagic Cell Death and Mitochondrial Damage via Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. Toxicol. Vitr. 2013, 27, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Ding, F.; Li, L.; Sun, Z. Role of the Dissolved Zinc Ion and Reactive Oxygen Species in Cytotoxicity of ZnO Nanoparticles. Toxicol. Lett. 2010, 199, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Hou, J.; Dai, S.; Wang, P.; Miao, L.; Lv, B.; Yang, Y.; You, G. Effects of ZnO Nanoparticles and Zn2+ on Fluvial Biofilms and the Related Toxicity Mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 544, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benavides, M.; Fernández-Lodeiro, J.; Coelho, P.; Lodeiro, C.; Diniz, M.S. Single and Combined Effects of Aluminum (Al2O3) and Zinc (ZnO) Oxide Nanoparticles in a Freshwater Fish, Carassius auratus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 24578–24591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, L.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, S.; Yu, X. Exposure to Mutagenic Disinfection Byproducts Leads to Increase of Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 8188–8195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyrzykowska, E.; Mikolajczyk, A.; Lynch, I.; Jeliazkova, N.; Kochev, N.; Sarimveis, H.; Doganis, P.; Karatzas, P.; Afantitis, A.; Melagraki, G.; et al. Representing and Describing Nanomaterials in Predictive Nanoinformatics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 924–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, A.; Xia, T.; Meng, H.; Wang, X.; Lin, S.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, H. Nanomaterial Toxicity Testing in the 21st Century: Use of a Predictive Toxicological Approach and High-Throughput Screening. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, A.M.; Judson, R.S.; Houck, K.A.; Grulke, C.M.; Volarath, P.; Thillainadarajah, I.; Yang, C.; Rathman, J.; Martin, M.T.; Wambaugh, J.F.; et al. ToxCast Chemical Landscape: Paving the Road to 21st Century Toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29, 1225–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese Robinson, R.L.; Lynch, I.; Peijnenburg, W.; Rumble, J.; Klaessig, F.; Marquardt, C.; Rauscher, H.; Puzyn, T.; Purian, R.; Åberg, C.; et al. How Should the Completeness and Quality of Curated Nanomaterial Data Be Evaluated? Nanoscale 2016, 8, 9919–9943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturla, S.J.; Boobis, A.R.; FitzGerald, R.E.; Hoeng, J.; Kavlock, R.J.; Schirmer, K.; Whelan, M.; Wilks, M.F.; Peitsch, M.C. Systems Toxicology: From Basic Research to Risk Assessment. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2014, 27, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, T.; FitzGerald, R.E.; Jennings, P.; Mirams, G.R.; Peitsch, M.C.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A.; Shah, I.; Wilks, M.F.; Sturla, S.J. Systems Toxicology: Real World Applications and Opportunities. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2017, 30, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadeel, B.; Farcal, L.; Hardy, B.; Vázquez-Campos, S.; Hristozov, D.; Marcomini, A.; Lynch, I.; Valsami-Jones, E.; Alenius, H.; Savolainen, K. Advanced Tools for the Safety Assessment of Nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NPs | NP Property Associated with Toxicity | Toxicological Phenomenon Observed/Mode of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Metal | Shedding heavy metal (e.g., Ag, Cu, Pt) | DNA cleavage and damage leading to genotoxicity and mutation; heavy metal ions induced oxidative stress and inflammatory responses [24]. |

| Metal Oxide | Dissolution and heavy metal release (e.g., ZnO) | Heavy metal ions induced oxidative stress and inflammatory responses [2]. |

| Silica Particles | Surface defects | Blood platelet, vascular endothelial, and clotting abnormalities [13]. |

| Fullerenes and CNTs | Heavy metal contamination | Fibrogenesis and tissue remodeling injury, oxygen radical production, Glutathione (GSH) depletion, bio-catalytic mechanisms [25]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neogi, N.; Choudhury, K.P.; Hossain, S.; Sazid, M.G.; Hossain, I. Advancing Nanotoxicology: High-Throughput Screening for Assessing the Toxicity of Nanoparticle Mixtures. Environ. Earth Sci. Proc. 2025, 37, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025037002

Neogi N, Choudhury KP, Hossain S, Sazid MG, Hossain I. Advancing Nanotoxicology: High-Throughput Screening for Assessing the Toxicity of Nanoparticle Mixtures. Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings. 2025; 37(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025037002

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeogi, Newton, Kristi Priya Choudhury, Sabbir Hossain, Md. Golam Sazid, and Ibrahim Hossain. 2025. "Advancing Nanotoxicology: High-Throughput Screening for Assessing the Toxicity of Nanoparticle Mixtures" Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings 37, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025037002

APA StyleNeogi, N., Choudhury, K. P., Hossain, S., Sazid, M. G., & Hossain, I. (2025). Advancing Nanotoxicology: High-Throughput Screening for Assessing the Toxicity of Nanoparticle Mixtures. Environmental and Earth Sciences Proceedings, 37(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/eesp2025037002