1. Challenges

The issues that ice and snow scholars are defining and addressing are becoming more urgent, coupled with the increasing scope of such issues. Fundamental research questions remain at the forefront of ice and snow research, including those related to the mineral properties of ice and the measurement and detection of changes to ice and snow around the world. Current issues are driven by a changing climate, land use modification, and conflict, with solutions in some cases being confined by political pressures. While the challenges have become larger, the opportunities to expand our knowledge of ice and snow have increased greatly.

Above, I used the word “scholars” as a more expansive term to refer to the people who work in this field. A vast majority of researchers working in the realm of ice and snow consider themselves scientists, with many working on issues related to physics-based questions. Other scientists are working to resolve chemistry, biology, ecology and related questions. Those whose work includes a human component may call themselves social scientists. And there are other scholars who work in the humanities and associated fields. To address some of the current issues, we will need to work in multi-disciplinary [

1], likely inter-disciplinary [

2], and in some cases even trans-disciplinary teams [

3]. We also need to continue investigating fundamental and applied questions within our own disciplines.

2. Using Personal Inspiration

Our work is often motivated by what inspires us. We make observations that provoke our curiosity and feed the questions that we ask. We need to continue to find inspiration in our subject matter. We may be wandering through the forests as the snow accumulates on the trees, peering at a glacier as we drive along the ring road in Iceland, looking at pan ice flowing along a freezing river, or even looking in our freezer for a forgotten container of sorbet. As scholars we tend to always be thinking about our subject matter; sharing what we observe helps us see and explaining helps us understand. Having conversations with scholars in other disciplines may give us new insights.

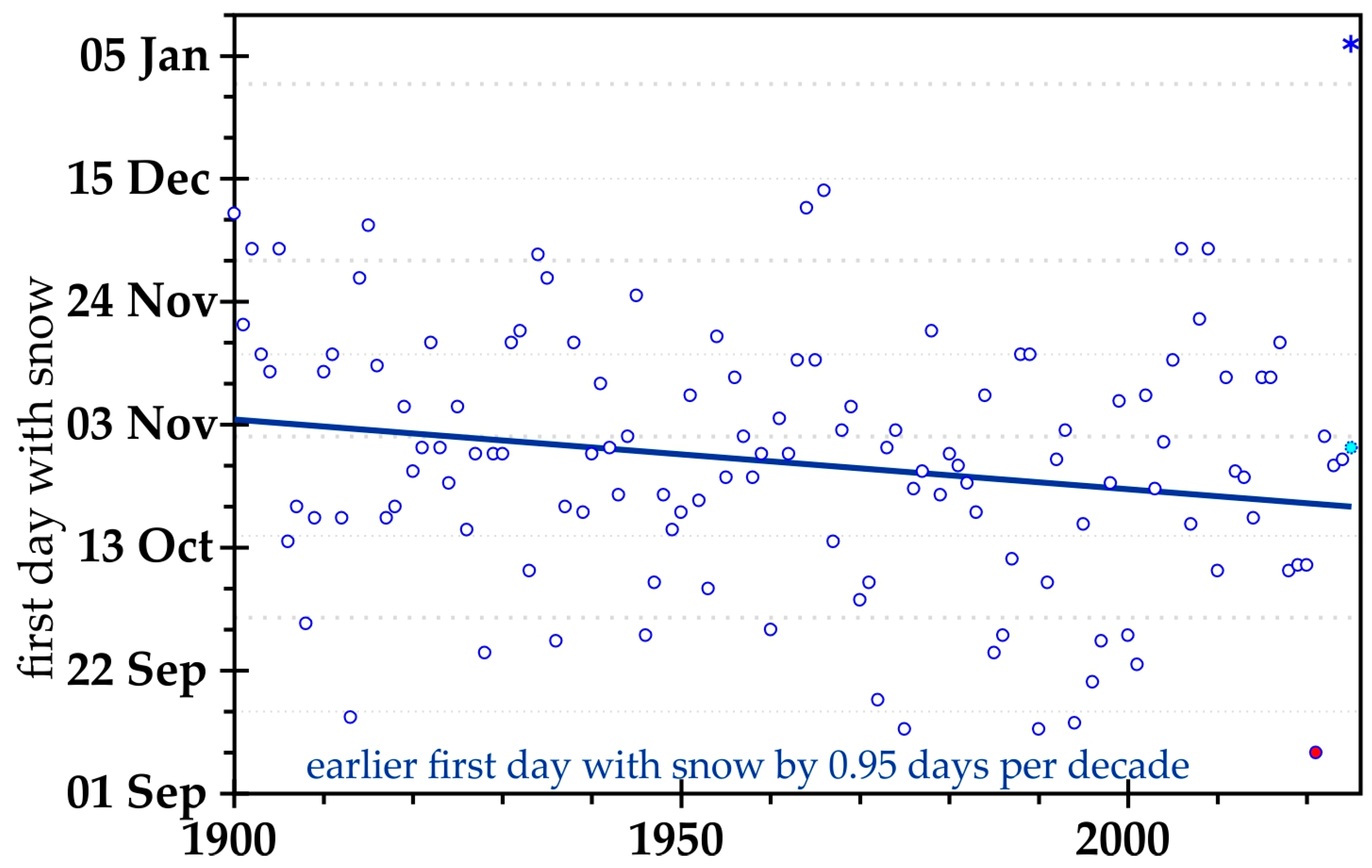

For me, an example is the first snowfall of the season. The fall of 2024 saw the latest arrival of the first snow on Japan’s Mount Fuji, recorded in the 130 years of meteorological data [

4]. Snow fell on 7 November 2024, 12 days after the previous latest arrival of snowfall (on 26 October in 1955 and 2016) [

5]. The first snowfall on 20 October 2024 on Mount Asahidake, the tallest peak on the Japanese Island of Hokkaidō, was also the latest recorded date over the last 136 years [

5].

When, on 29 October 2024, I read that there was no snow yet on Mount Fuji [

4], I thought about the first snowfall where I live in Fort Collins, Colorado, USA (

Figure 1). Over the two decades that I have lived here, I have thought about, measured [

6], and analyzed the local snowpack data. The Colorado State University weather station has a similar period of records to Mount Fuji and Mount Asahidake.

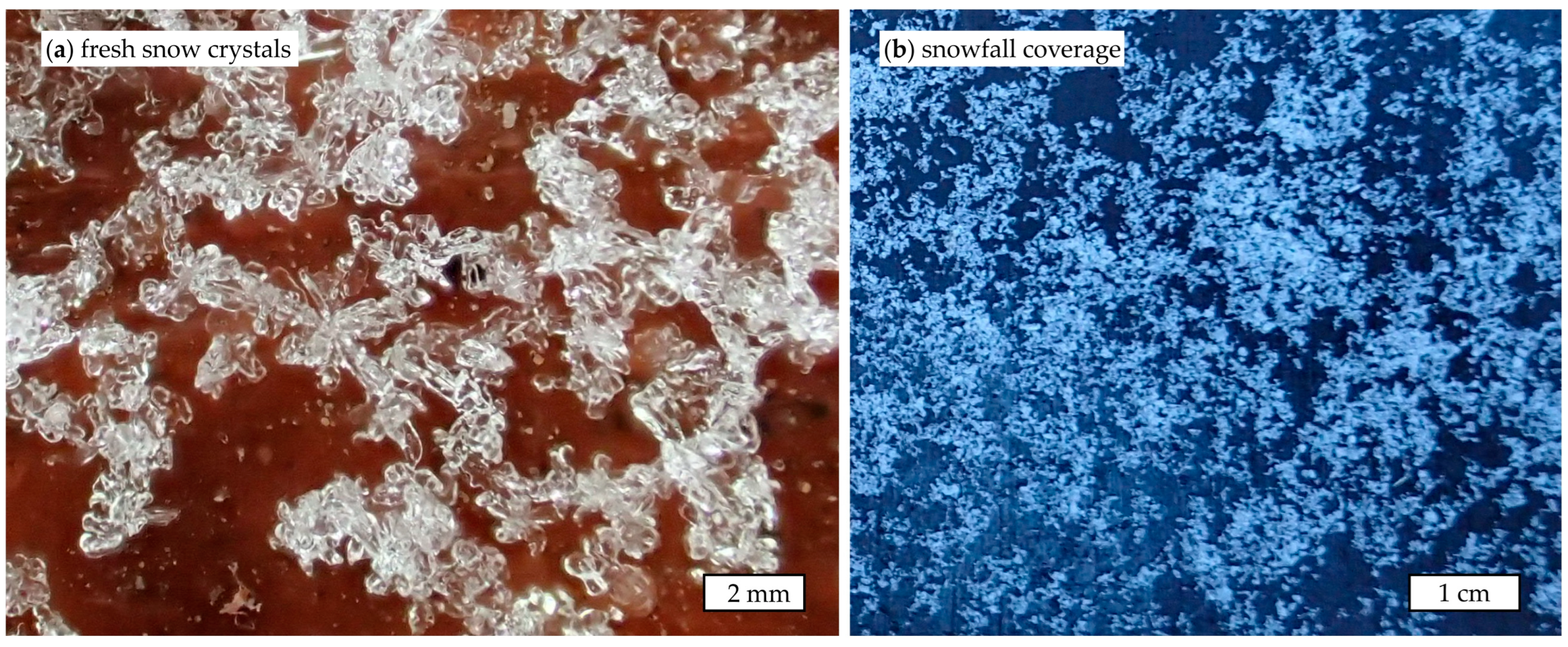

Since I moved to Fort Collins in 2002, the first snow occurs, on average, at the end of October, occurring as early as 8 September (in 2020) or as late as 3 December (in 2008). According to the Fort Collins meteorological observations (since 1893), a scant 0.25 cm of fresh snow fell on 30 October 2024, but no snow was measured on the ground. It snowed again on 8 November 2024, where 2.5 cm of snow was observed on the ground on campus. But I only saw a smattering of snow crystals on that day (

Figure 2a) that did not cover the ground (

Figure 2b). The next snowfall was on 07 January 2025 (

Figure 1), and for me this was the first full snow cover. I attribute the difference to spatial variability [

6]. Interestingly, the first snowfall on 8 September 2020 is the earliest snowfall on record, and it occurred two days after the maximum temperature was 37.3 degrees Celsius. The very warm day followed by the earliest snowfall recorded to date occurred when the largest observed fire in Colorado was burning due west of Fort Collins [

7]. These extremes from the earliest recorded snowfall in 2020 to possibly (

Figure 1) the latest snowfall on record, four months later, highlights the increasingly uncertain time that we now live in.

I live in a location where there is snow. I shovel that snow to clear the sidewalk and think about the properties of snow. I think about the plastic–elastic properties of snow when it hangs in the air off the bumper of a vehicle. When I take holidays at a ski resort, I ponder the spatial variability of snowpack properties across an elevational gradient and, occasionally, the difference between the snow in open versus forested areas as I ski through a glade. Being amongst my medium, snow, inspires me.

Figure 1.

The first day of snow in Fort Collins, Colorado, USA (National Weather Service station USC00053005 [

8]) from 1900 to 2024. The trend in the first snowfall date becoming earlier is significant [

9,

10]. The first snowfall in 2020 is depicted as a filled red dot, the first snowfall in 2024 recorded by the NWS station is depicted as a filled blue dot, and the first snowfall in 2024 observed by the author is depicted as a blue asterisk.

Figure 1.

The first day of snow in Fort Collins, Colorado, USA (National Weather Service station USC00053005 [

8]) from 1900 to 2024. The trend in the first snowfall date becoming earlier is significant [

9,

10]. The first snowfall in 2020 is depicted as a filled red dot, the first snowfall in 2024 recorded by the NWS station is depicted as a filled blue dot, and the first snowfall in 2024 observed by the author is depicted as a blue asterisk.

Figure 2.

Photographs of the snowfall on 8 November 2024: (a) snow crystal form and (b) snow coverage, on a black board in northern Fort Collins, Colorado, USA. The scale bar for each photograph is shown in the lower left-hand corner. The photographs were taken by the author.

Figure 2.

Photographs of the snowfall on 8 November 2024: (a) snow crystal form and (b) snow coverage, on a black board in northern Fort Collins, Colorado, USA. The scale bar for each photograph is shown in the lower left-hand corner. The photographs were taken by the author.

3. Opportunities

As ice and snow scientists and scholars, we have an opportunity to further develop our understanding of ice as a mineral and to investigate atmospheric ice, sea ice, freshwater ice, ice sheets, ice caps and ice shelves, glaciology, permafrost and frozen ground, snow hydrology, paleo ice investigations, ice and snow-related hazards, ice engineering, snow ecosystems, and beyond. The journal Glacies (ISSN 2813-8740) is an ideal platform for the submissions of papers in the form of articles, technical notes, reviews, communications, editorials, essays, etc. You are encouraged to use your inspirations to identify and address a problem, concept, or challenge. Those inspirations may be derived from personal experiences, conversations with those without such knowledge and those outside of your field, or gaps in the literature.

Not every paper needs to be cross-disciplinary or multi-authored. We gain new and different insights from other perspectives, and new collaborations will lead to a new understanding and new approaches. Papers from any ice and snow perspective of physics, chemistry, biology, ecology, social science, education, the humanities, etc., and any combinations thereof are encouraged.

Glacies will consider all well-constructed, high-quality submissions, as well as Special Issues related to ice and snow (see

https://www.mdpi.com/journal/glacies/about (accessed on 21 January 2025). At present, there is a Special Issue title Advances in River Ice Research (edited by Editorial Board Member Professor Dr. Hung Tao Shen).

Two issues have been published to date in Glacies, covering a variety of topics and different types of scholarship. I would like to take this opportunity to thank the authors, readers, reviewers, Editorial Board Members, and members of the Glacies editorial team for allowing the journal to start off strong. Your participation in any of the aforementioned roles will help build an impactful volume 2 and beyond.