Histamine Deficiency Inhibits Lymphocyte Infiltration in the Lacrimal Gland of Aged Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

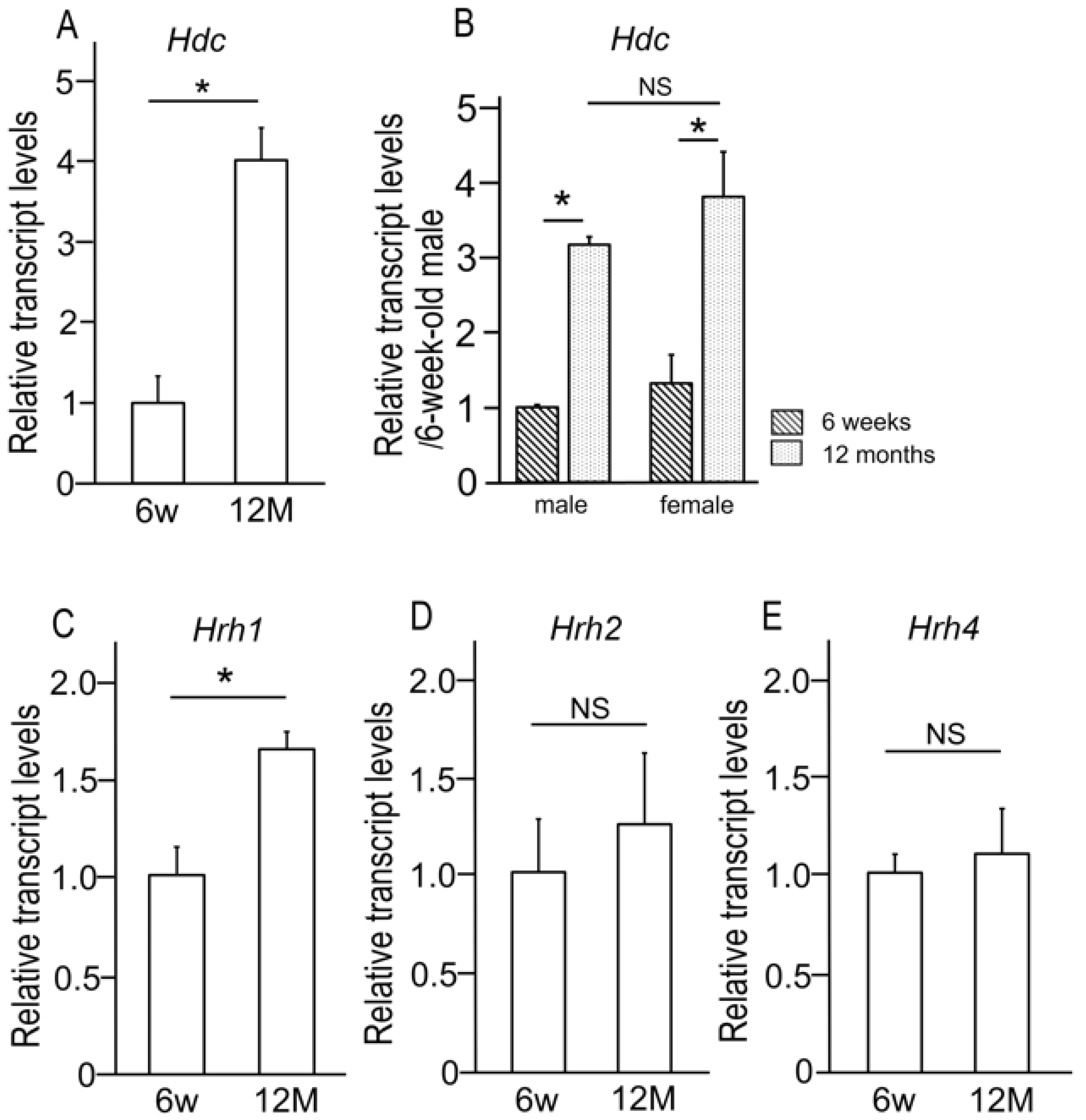

2.1. Age-Related Alterations in the Expression of Histidine Decarboxylase and Histamine Receptors in the Lacrimal Gland

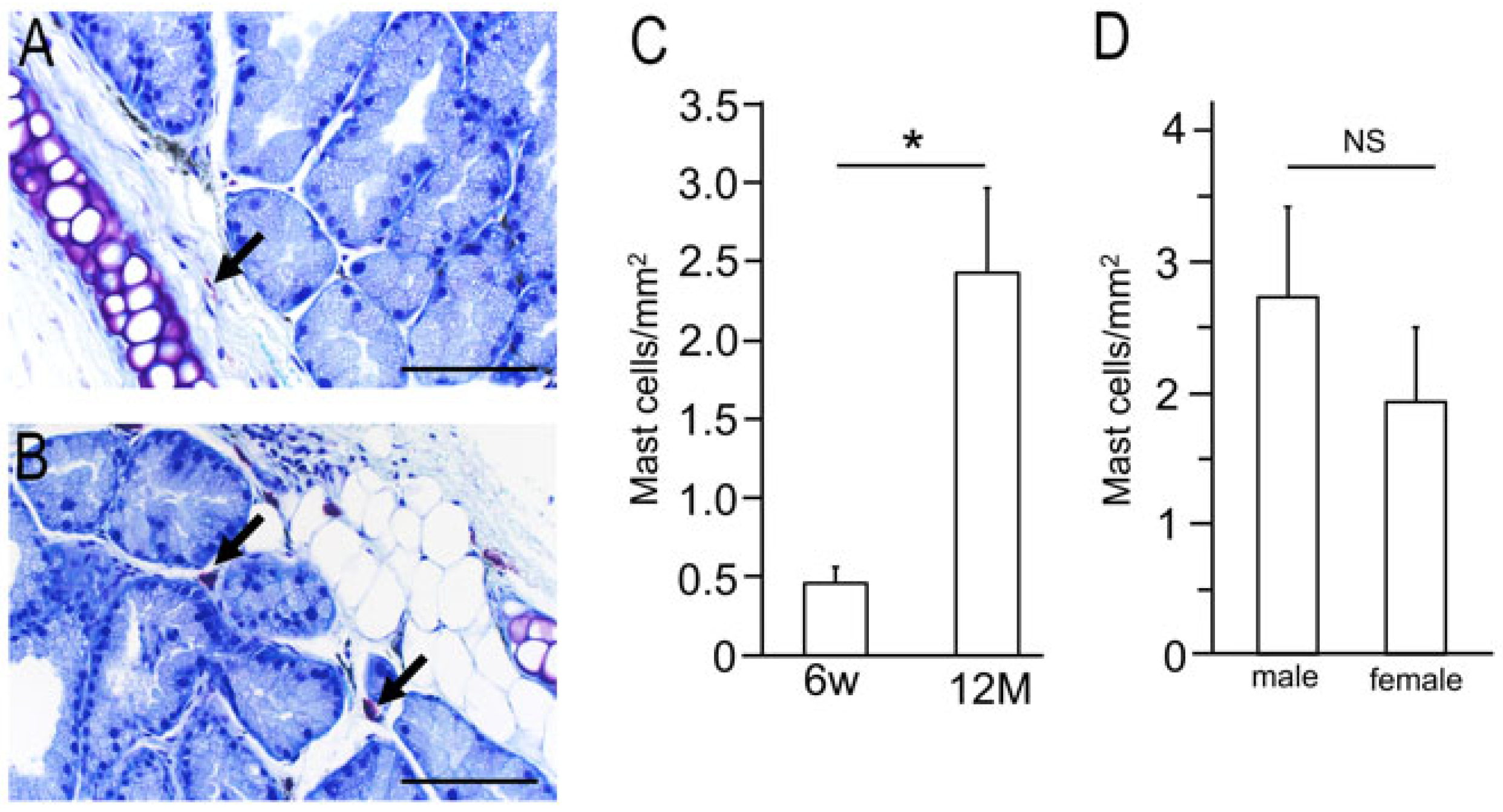

2.2. Isolation of Mast Cells from Lacrimal Glands of 6-Week and 12-Month-Old Wild-Type Mice

2.3. Age-Related Morphological Changes in Lacrimal Gland Tissue

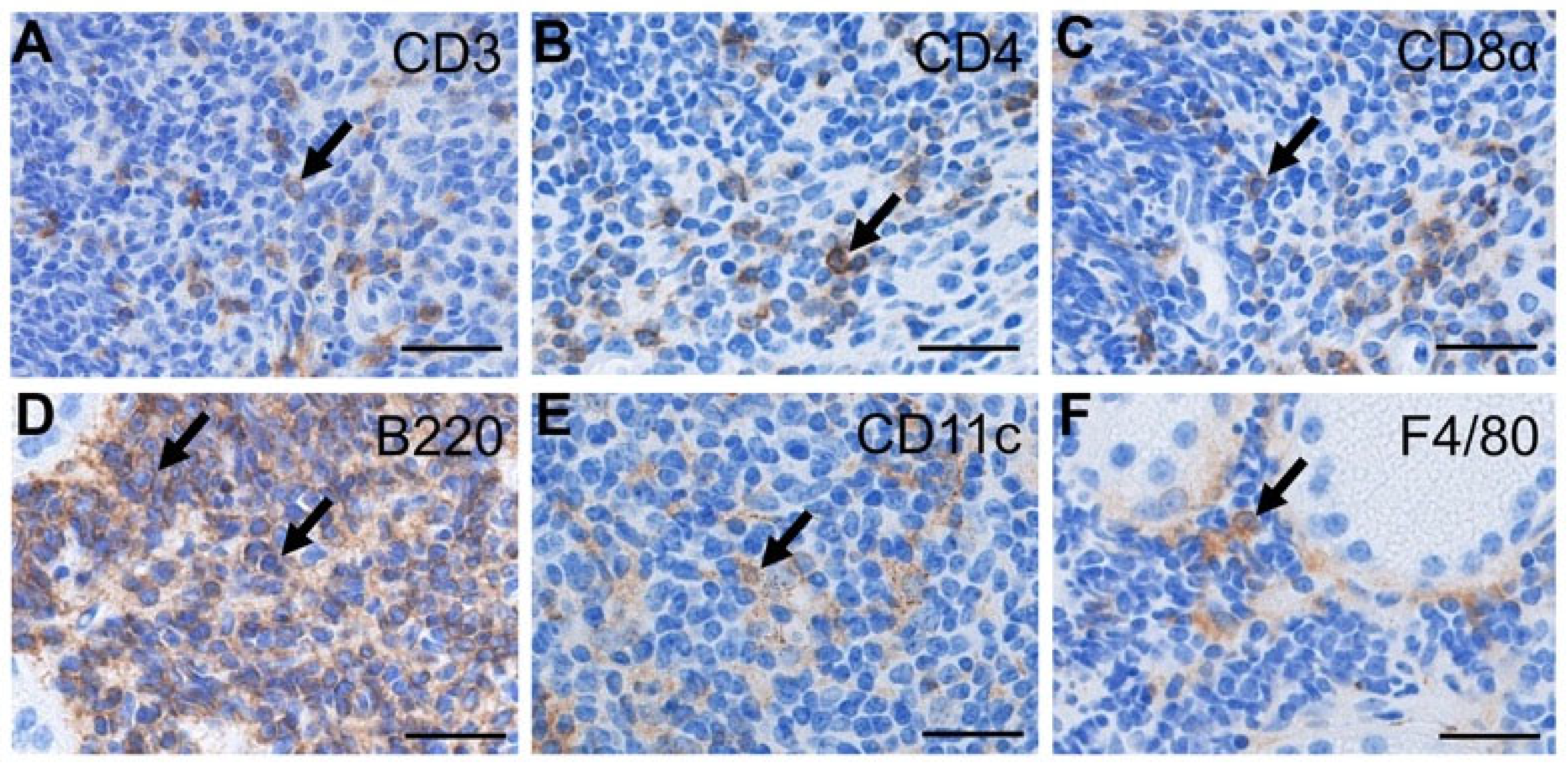

2.4. Identification of Infiltrating Cells in the Lacrimal Glands of Aged Wild-Type Mice

2.5. The Age-Related Changes of Inflammatory Associated Cytokines Expression in the Lacrimal Gland

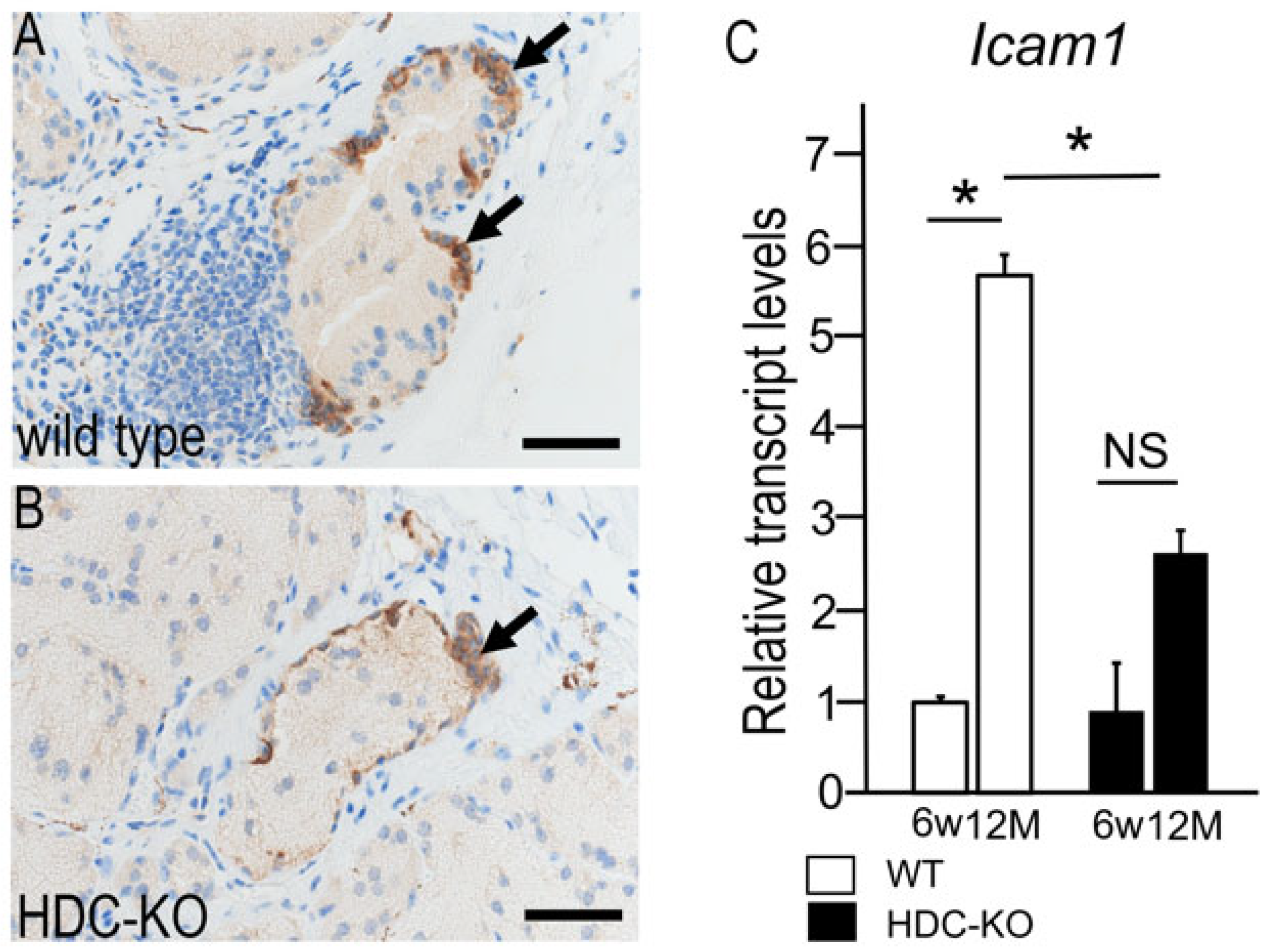

2.6. Changes in Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1) Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Antibodies

4.3. Tissue Preparation for Histology and Immunohistochemical Staining

4.4. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

4.5. Histological Quantification and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HDC | Histidine decarboxylase |

| RT-qPCR | Reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| NBP | Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonate |

| TB | Tolidine blue |

| HE | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

References

- Dy, M.; Schneider, E. Histamine-cytokine connection in immunity and hematopoiesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004, 15, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkhtaivan, E.; Lee, C.H. Role of Amine Neurotransmitters and Their Receptors in Skin Pigmentation: Therapeutic Implication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Q.; Yao, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, X.; Saito, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, P.; et al. The allergy mediator histamine confers resistance to immunotherapy in cancer patients via activation of the macrophage histamine receptor H1. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 36–52.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giustizieri, M.L.; Albanesi, C.; Fluhr, J.; Gisondi, P.; Norgauer, J.; Girolomoni, G. H1 histamine receptor mediates inflammatory responses in human keratinocytes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 114, 1176–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, P. The basics of histamine biology. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011, 106, S2–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saligrama, N.; Noubade, R.; Case, L.K.; del Rio, R.; Teuscher, C. Combinatorial roles for histamine H1-H2 and H3-H4 receptors in autoimmune inflammatory disease of the central nervous system. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 1536–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegaev, V.; Sillat, T.; Porola, P.; Hänninen, A.; Falus, A.; Mieliauskaite, D.; Buzás, E.; Rotar, Z.; Mackiewicz, Z.; Stark, H.; et al. Brief report: First identification of H4 histamine receptor in healthy salivary glands and in focal sialadenitis in Sjögren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 2663–2668. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, Y. Induction of histidine decarboxylase in mouse tissues by mitogens in vivo. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1983, 32, 3835–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Yu, Z.; Funayama, H.; Shoji, N.; Sasano, T.; Iwakura, Y.; Sugawara, S.; Endo, Y. Mutual augmentation of the induction of the histamine-forming enzyme, histidine decarboxylase, between alendronate and immuno-stimulants (IL-1, TNF, and LPS), and its prevention by clodronate. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2006, 213, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, H.; Endo, Y.; Ohtsu, H.; Inoue, S.; Noguchi, S.; Nakamura, M.; Soeta, S. Histidine decarboxylase deficiency inhibits NBP-induced extramedullary hematopoiesis by modifying bone marrow and spleen microenvironments. Int. J. Hematol. 2021, 113, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohda, F.; Koga, T.; Uchi, H.; Urabe, K.; Furue, M. Histamine-induced IL-6 and IL-8 production are differentially modulated by IFN-gamma and IL-4 in human keratinocytes. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2002, 28, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Ai, J.; Wei, X. Histamine and histamine receptor H1 (HRH1) axis: New target for enhancing immunotherapy response. Mol. Biomed. 2022, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, Y.; Kikuchi, T.; Takeda, Y.; Nitta, Y.; Rikiishi, H.; Kumagai, K. GM-CSF and G-CSF stimulate the synthesis of histamine and putrescine in the hematopoietic organs in vivo. Immunol. Lett. 1992, 33, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcagni, E.; Elenkov, I. Stress system activity, innate and T helper cytokines, and susceptibility to immune-related diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1069, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, J.H.; Yanai, K.; Sakurai, E.; Kim, C.Y.; Watanabe, T. Ontogenetic development of histamine receptor subtypes in rat brain demonstrated by quantitative autoradiography. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1995, 87, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Deng, H.; Churchill, M.J.; Luchsinger, L.L.; Du, X.; Chu, T.H.; Friedman, R.A.; Middelhoff, M.; Ding, H.; Tailor, Y.H.; et al. Bone Marrow Myeloid Cells Regulate Myeloid-Biased Hematopoietic Stem Cells via a Histamine-Dependent Feedback Loop. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 747–760.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamutdinova, I.T.; Maejima, D.; Nagai, T.; Meininger, C.J.; Gashev, A.A. Histamine as an Endothelium-Derived Relaxing Factor in Aged Mesenteric Lymphatic Vessels. Lymphat. Res. Biol. 2017, 15, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinas, E.; Kritas, S.K.; Saggini, A.; Mobili, A.; Caraffa, A.; Antinolfi, P.; Pantalone, A.; Tei, M.; Speziali, A.; Saggini, R.; et al. Role of mast cells in atherosclerosis: A classical inflammatory disease. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2014, 27, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boren, E.; Gershwin, M.E. Inflamm-aging: Autoimmunity, and the immune-risk phenotype. Autoimmun. Rev. 2004, 3, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrisette-Thomas, V.; Cohen, A.A.; Fulop, T.; Riesco, E.; Legault, V.; Li, Q.; Milot, E.; Dusseault-Belanger, F.; Ferrucci, L. Inflamm-aging does not simply reflect increases in pro-inflammatory markers. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2014, 139, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, H.; Nonaka, N.; Nakamura, M.; Soeta, S. Histamine deficiency inhibits lymphocyte infiltration in the submandibular gland of aged mice via increased anti-aging factor Klotho. J. Oral Biosci. 2023, 65, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, R.; Brokstad, K.A.; Jonsson, M.V.; Delaleu, N.; Skarstein, K. Current concepts on Sjögren’s syndrome—Classification criteria and biomarkers. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 126, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrini, S.; Emmi, G.; Greco, M.; Borro, M.; Sardanelli, F.; Murdaca, G.; Indiveri, F.; Puppo, F. Sjögren’s syndrome: A systemic autoimmune disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2022, 22, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjordal, O.; Norheim, K.B.; Rødahl, E.; Jonsson, R.; Omdal, R. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome and the eye. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2020, 65, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Montoya, J.A.; Silvestre, F.J.; Barrios, R.; Silvestre-Rangil, J. Treatment of xerostomia and hyposalivation in the elderly: A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Y Cir. Bucal 2016, 21, e355–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Utsuyama, M.; Kurashima, C.; Hirokawa, K. Spontaneous development of organ-specific autoimmune lesions in aged C57BL/6 mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1989, 78, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A.; Chanal, I.; Czarlewski, W.; Michel, F.B.; Bousquet, J. Reduction of soluble ICAM-1 levels in nasal secretion by H1-blockers in seasonal allergic rhinitis. Allergy 1997, 52, 1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Ciprandi, G.; Cosentino, C.; Milanese, M.; Tosca, M.A. Rapid anti-inflammatory action of azelastine eyedrops for ongoing allergic reactions. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003, 90, 434–438. [Google Scholar]

- Nori, M.; Iwata, S.; Munakata, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Umezawa, Y.; Hosono, O.; Kawasaki, H.; Dang, N.H.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Ebastine inhibits T cell migration, production of Th2-type cytokines and proinflammatory cytokines. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2003, 33, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Iwata, S.; Ohnuma, K.; Dang, N.H.; Morimoto, C. Histamine H1-receptor antagonists with immunomodulating activities: Potential use for modulating T helper type 1 (Th1)/Th2 cytokine imbalance and inflammatory responses in allergic diseases. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 157, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenke-Layland, K.; Xie, J.; Magnusson, M.; Angelis, E.; Li, X.; Wu, K.; Reinhardt, D.P.; Maclellan, W.R.; Hamm-Alvarez, S.F. Lymphocytic infiltration leads to degradation of lacrimal gland extracellular matrix structures in NOD mice exhibiting a Sjögren’s syndrome-like exocrinopathy. Exp. Eye Res. 2010, 90, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranyuk, Y.; Claros, N.; Birzgalis, A.; Moore, L.C.; Brink, P.R.; Walcott, B. Lacrimal gland fluid secretion and lymphocytic infiltration in the NZB/W mouse model of Sjögren’s syndrome. Curr. Eye Res. 2001, 23, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaštelan, S.; Hat, K.; Tomić, Z.; Matejić, T.; Gotovac, N. Sex Differences in the Lacrimal Gland: Implications for Dry Eye Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimura, Y.; Tachibana, H.; Yamada, K. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands negatively regulate the expression of the high-affinity IgE receptor Fc epsilon RI in human basophilic KU812 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 297, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Luo, S.; Zhan, Y.; Lu, Q. The roles of PPARγ and its agonists in autoimmune diseases: A comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 113, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błochowiak, K.J.; Olewicz-Gawlik, A.; Trzybulska, D.; Nowak-Gabryel, M.; Kocięcki, J.; Witmanowski, H.; Sokalski, J. Serum ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin levels in patients with primary and secondary Sjögren’s syndrome. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Off. Organ Wroc. Med. Univ. 2017, 26, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickelson, J.K.; Kukielka, G.; Bravenec, J.S.; Mainolfi, E.; Rothlein, R.; Hawkins, H.K.; Kelly, J.H.; Smith, C.W. Differential expression and release of CD54 induced by cytokines. Hepatology 1995, 22, 866–875. [Google Scholar]

- McHale, J.F.; Harari, O.A.; Marshall, D.; Haskard, D.O. TNF-alpha and IL-1 sequentially induce endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression in MRL/lpr lupus-prone mice. J. Immunol. 1999, 163, 3993–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghayegh Jahromi, N.; Marchetti, L.; Moalli, F.; Duc, D.; Basso, C.; Tardent, H.; Kaba, E.; Deutsch, U.; Pot, C.; Sallusto, F.; et al. Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and ICAM-2 Differentially Contribute to Peripheral Activation and CNS Entry of Autoaggressive Th1 and Th17 Cells in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsu, H.; Tanaka, S.; Terui, T.; Hori, Y.; Makabe-Kobayashi, Y.; Pejler, G.; Tchougounova, E.; Hellman, L.; Gertsenstein, M.; Hirasawa, N.; et al. Mice lacking histidine decarboxylase exhibit abnormal mast cells. FEBS Lett. 2001, 502, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, H.; Endo, Y.; Ohtsu, H.; Inoue, S.; Kuraoka, M.; Koh, M.; Yagi, H.; Nakamura, M.; Soeta, S. Changes in histidine decarboxylase expression influence extramedullary hematopoiesis in postnatal mice. Anat. Rec. 2021, 304, 1136–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, K.V.; Sonia, G.; Shrestha, P.; Hemadala, G. A Comparative Study of Mast Cells Count in Different Histological Grades of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Using Toluidine Blue Stain. Cureus 2020, 12, e10626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Hdc | F: 5′-TTCCAGCCTCCTCTGTCTGT-3′ R: 5′-GGTATCCAGGCTGCACATTT-3′ |

| Hrh1 | F: 5′-GGGAAAHHHAAACAGTCACA-3′ R: 5′-ACTGTCGATCCACCAAGGTC-3′ |

| Hrh2 | F: 5′-CAGCTTCCATCCTCAACCTC-3′ R: 5′-GACCTGCACTTTGCACTTGA-3′ |

| Hrh4 | F: 5′-GAATCAGCTGCATCTCGTCA-3′ R: 5′-GTGACCTGGCTAGCTTCCTG-3′ |

| Tnfa | F: 5′-TATGGCTCAGGGTCCAACTC-3′ R: 5′-CTCCCTTTGCAGAACTCAGG-3′ |

| Il1b | F: 5′-GCCCATCCTCTGTGACTCAT-3′ R: 5′-AGGCCACAGGTATTTTGTCG-3′ |

| Il6 | F: 5′-AGTTGCCTTCTTGGGACTGA-3′ R: 5′-TCCACGATTTCCCAGAGAAC-3′ |

| Pparγ | F: 5′-TTTTCAAGGGTGCCAGTTTC-3′ R: 5′-AATCCTTGGCCCTCTGAGAT-3′ |

| Icam-1 | F: 5′-AGCACCTCCCCACCTACTTT-3′ R: 5′-AGCTTGCACGACCCTTCTAA-3′ |

| Actb | F: 5′-GCGTGACATTAAAGAGAAGCTG-3′ R: 5′-CTCAGGAGGAGCAATGATCTTG-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Otsuka, H.; Tsunoyama, Y.; Koh, M.; Soeta, S.; Nonaka, N. Histamine Deficiency Inhibits Lymphocyte Infiltration in the Lacrimal Gland of Aged Mice. Lymphatics 2025, 3, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040048

Otsuka H, Tsunoyama Y, Koh M, Soeta S, Nonaka N. Histamine Deficiency Inhibits Lymphocyte Infiltration in the Lacrimal Gland of Aged Mice. Lymphatics. 2025; 3(4):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040048

Chicago/Turabian StyleOtsuka, Hirotada, Yusuke Tsunoyama, Miki Koh, Satoshi Soeta, and Naoko Nonaka. 2025. "Histamine Deficiency Inhibits Lymphocyte Infiltration in the Lacrimal Gland of Aged Mice" Lymphatics 3, no. 4: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040048

APA StyleOtsuka, H., Tsunoyama, Y., Koh, M., Soeta, S., & Nonaka, N. (2025). Histamine Deficiency Inhibits Lymphocyte Infiltration in the Lacrimal Gland of Aged Mice. Lymphatics, 3(4), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040048