Functional Intraclonal Heterogeneity in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Proliferation vs. Quiescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

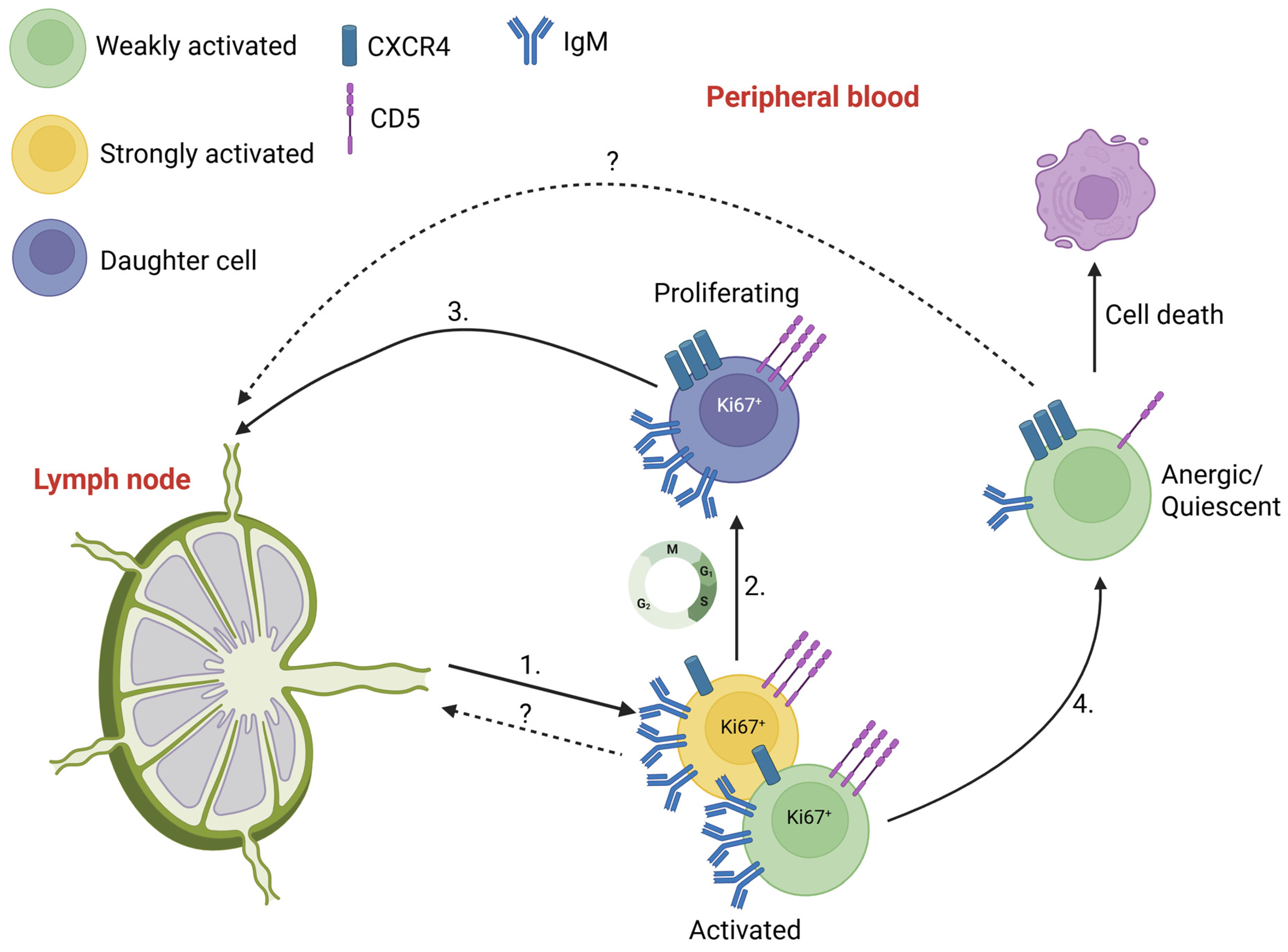

2. Activated, Proliferative and Quiescent States of CLL Cells

2.1. Migration of Activated and Proliferative CLL Cells

2.2. Re-Activation of Quiescent Cells

3. Discussion

4. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Messmer, B.T.; Messmer, D.; Allen, S.L.; Kolitz, J.E.; Kudalkar, P.; Cesar, D.; Murphy, E.J.; Koduru, P.; Ferrarini, M.; Zupo, S.; et al. In vivo measurements document the dynamic cellular kinetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gent, R.; Kater, A.P.; Otto, S.A.; Jaspers, A.; Borghans, J.A.; Vrisekoop, N.; Ackermans, M.A.; Ruiter, A.F.; Wittebol, S.; Eldering, E.; et al. In vivo dynamics of stable chronic lymphocytic leukemia inversely correlate with somatic hypermutation levels and suggest no major leukemic turnover in bone marrow. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 10137–10144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.; Chen, L.; Zhang, S.; Mraz, M.; Fecteau, J.F.; Yu, J.; Ghia, E.M.; Zhang, L.; Bao, L.; Rassenti, L.Z.; et al. MicroRNA-155 influences B-cell receptor signaling and associates with aggressive disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2014, 124, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packham, G.; Krysov, S.; Allen, A.; Savelyeva, N.; Steele, A.J.; Forconi, F.; Stevenson, F.K. The outcome of B-cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Proliferation or anergy. Haematologica 2014, 99, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forconi, F.; Lanham, S.A.; Chiodin, G. Biological and Clinical Insight from Analysis of the Tumor B-Cell Receptor Structure and Function in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancers 2022, 14, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herndon, T.M.; Chen, S.S.; Saba, N.S.; Valdez, J.; Emson, C.; Gatmaitan, M.; Tian, X.; Hughes, T.E.; Sun, C.; Arthur, D.C.; et al. Direct in vivo evidence for increased proliferation of CLL cells in lymph nodes compared to bone marrow and peripheral blood. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1340–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, P.E.; Buggins, A.G.; Richards, J.; Wotherspoon, A.; Salisbury, J.; Mufti, G.J.; Hamblin, T.J.; Devereux, S. CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia is regulated by the tumor microenvironment. Blood 2008, 111, 5173–5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gine, E.; Martinez, A.; Villamor, N.; Lopez-Guillermo, A.; Camos, M.; Martinez, D.; Esteve, J.; Calvo, X.; Muntanola, A.; Abrisqueta, P.; et al. Expanded and highly active proliferation centers identify a histological subtype of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (“accelerated” chronic lymphocytic leukemia) with aggressive clinical behavior. Haematologica 2010, 95, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herishanu, Y.; Perez-Galan, P.; Liu, D.; Biancotto, A.; Pittaluga, S.; Vire, B.; Gibellini, F.; Njuguna, N.; Lee, E.; Stennett, L.; et al. The lymph node microenvironment promotes B-cell receptor signaling, NF-kappaB activation, and tumor proliferation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2011, 117, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, E.M.; Pepper, A.; Mele, S.; Folarin, N.; Townsend, W.; Cuthill, K.; Phillips, E.H.; Patten, P.E.M.; Devereux, S. In vitro and in vivo evidence for uncoupling of B-cell receptor internalization and signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica 2018, 103, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselager, M.V.; Kater, A.P.; Eldering, E. Proliferative Signals in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia; What Are We Missing? Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 592205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.; Nadeu, F.; Colomer, D.; Campo, E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: From molecular pathogenesis to novel therapeutic strategies. Haematologica 2020, 105, 2205–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Chen, Y.C.; Martinez Zurita, A.; Baptista, M.J.; Pittaluga, S.; Liu, D.; Rosebrock, D.; Gohil, S.H.; Saba, N.S.; Davies-Hill, T.; et al. The immune microenvironment shapes transcriptional and genetic heterogeneity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, D.; Mehtani, D.P.; Vidler, J.B.; Patten, P.E.M.; Hoogeboom, R. Proliferating CLL cells express high levels of CXCR4 and CD5. Hemasphere 2024, 8, e70064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calissano, C.; Damle, R.N.; Hayes, G.; Murphy, E.J.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Moreno, C.; Sison, C.; Kaufman, M.S.; Kolitz, J.E.; Allen, S.L.; et al. In vivo intraclonal and interclonal kinetic heterogeneity in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2009, 114, 4832–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calissano, C.; Damle, R.N.; Marsilio, S.; Yan, X.J.; Yancopoulos, S.; Hayes, G.; Emson, C.; Murphy, E.J.; Hellerstein, M.K.; Sison, C.; et al. Intraclonal complexity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Fractions enriched in recently born/divided and older/quiescent cells. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarello, A.N.; Fitch, M.; Cardillo, M.; Ng, A.; Bhuiya, S.; Sharma, E.; Bagnara, D.; Kolitz, J.E.; Barrientos, J.C.; Allen, S.L.; et al. Characterization of the Intraclonal Complexity of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia B Cells: Potential Influences of B-Cell Receptor Crosstalk with Other Stimuli. Cancers 2023, 15, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapaprieta, V.; Maiques-Diaz, A.; Nadeu, F.; Clot, G.; Massoni-Badosa, R.; Mozas, P.; Mateos-Jaimez, J.; Vidal, A.; Charalampopoulou, S.; Duran-Ferrer, M.; et al. Dual biological role and clinical impact of de novo chromatin activation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2025, 145, 2473–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, A.; Deglesne, P.A.; Letestu, R.; Saint-Georges, S.; Chevallier, N.; Baran-Marszak, F.; Varin-Blank, N.; Ajchenbaum-Cymbalista, F.; Ledoux, D. Down-regulation of CXCR4 and CD62L in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells is triggered by B-cell receptor ligation and associated with progressive disease. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 6387–6395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Hernandez, M.M.; Blunt, M.D.; Dobson, R.; Yeomans, A.; Thirdborough, S.; Larrayoz, M.; Smith, L.D.; Linley, A.; Strefford, J.C.; Davies, A.; et al. IL-4 enhances expression and function of surface IgM in CLL cells. Blood 2016, 127, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V.; Krysov, S.; Steele, A.; Sanchez Hidalgo, M.; Johnson, P.W.; Chana, P.S.; Packham, G.; Stevenson, F.K.; Forconi, F. Identification in CLL of circulating intraclonal subgroups with varying B-cell receptor expression and function. Blood 2013, 122, 2664–2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tissino, E.; Pozzo, F.; Benedetti, D.; Caldana, C.; Bittolo, T.; Rossi, F.M.; Bomben, R.; Nanni, P.; Chivilo, H.; Cattarossi, I.; et al. CD49d promotes disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: New insights from CD49d bimodal expression. Blood 2020, 135, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasikowska, M.; Walsby, E.; Apollonio, B.; Cuthill, K.; Phillips, E.; Coulter, E.; Longhi, M.S.; Ma, Y.; Yallop, D.; Barber, L.D.; et al. Phenotype and immune function of lymph node and peripheral blood CLL cells are linked to transendothelial migration. Blood 2016, 128, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Till, K.J.; Pettitt, A.R.; Slupsky, J.R. Expression of functional sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor-1 is reduced by B cell receptor signaling and increased by inhibition of PI3 kinase delta but not SYK or BTK in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 2439–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, M.; Beuling, E.A.; Rurup, M.L.; Meijer, H.P.; Klok, M.D.; Middendorp, S.; Hendriks, R.W.; Pals, S.T. The B cell antigen receptor controls integrin activity through Btk and PLCgamma2. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyster, J.G. B cell follicles and antigen encounters of the third kind. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rooij, M.F.; Kuil, A.; Geest, C.R.; Eldering, E.; Chang, B.Y.; Buggy, J.J.; Pals, S.T.; Spaargaren, M. The clinically active BTK inhibitor PCI-32765 targets B-cell receptor- and chemokine-controlled adhesion and migration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2012, 119, 2590–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, S.E.; Niemann, C.U.; Farooqui, M.; Jones, J.; Mustafa, R.Z.; Lipsky, A.; Saba, N.; Martyr, S.; Soto, S.; Valdez, J.; et al. Ibrutinib-induced lymphocytosis in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Correlative analyses from a phase II study. Leukemia 2014, 28, 2188–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Barroso, J.; Munaretto, A.; Rouquie, N.; Mougel, A.; Chassan, M.; Gadat, S.; Dewingle, O.; Poincloux, R.; Cadot, S.; Ysebaert, L.; et al. Lymphocyte migration and retention properties affected by ibrutinib in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica 2024, 109, 809–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassarino, M.C.; Colado, A.; Martinez, V.S.; Martines, C.; Bonato, A.; Bertini, M.; Pavlovksy, M.; Custidiano, R.; Bezares, F.R.; Morande, P.E.; et al. G-protein coupled receptor kinase-2 regulates the migration of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells to sphingosine-1 phosphate in vitro and their trafficking in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenti, E.; Visentin, E.; Bojnik, E.; Neroni, A.; Franchino, M.; Talarico, D.; Sacchetti, N.; Scarfo, L.; Maurizio, A.; Garcia-Manteiga, J.M.; et al. A spheroid model that recapitulates the protective role of the lymph node microenvironment and serves as a platform for drug testing in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hemasphere 2025, 9, e70170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselager, M.V.; van Driel, B.F.; Perelaer, E.; de Rooij, D.; Lashgari, D.; Loos, R.; Kater, A.P.; Moerland, P.D.; Eldering, E. In Vitro 3D Spheroid Culture System Displays Sustained T Cell-dependent CLL Proliferation and Survival. Hemasphere 2023, 7, e938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholdy, B.A.; Wang, X.; Yan, X.J.; Pascual, M.; Fan, M.; Barrientos, J.; Allen, S.L.; Martinez-Climent, J.A.; Rai, K.R.; Chiorazzi, N.; et al. CLL intraclonal fractions exhibit established and recently acquired patterns of DNA methylation. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Avola, A.; Drennan, S.; Tracy, I.; Henderson, I.; Chiecchio, L.; Larrayoz, M.; Rose-Zerilli, M.; Strefford, J.; Plass, C.; Johnson, P.W.; et al. Surface IgM expression and function are associated with clinical behavior, genetic abnormalities, and DNA methylation in CLL. Blood 2016, 128, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mockridge, C.I.; Potter, K.N.; Wheatley, I.; Neville, L.A.; Packham, G.; Stevenson, F.K. Reversible anergy of sIgM-mediated signaling in the two subsets of CLL defined by VH-gene mutational status. Blood 2007, 109, 4424–4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, L.; Chiorazzi, N.; Rothstein, T.L. IL-4 rescues surface IgM expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2016, 128, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, K.M.; Zhang, Y.; Pepper, A.; Boelen, L.; Coulter, E.; Asquith, B.; Devereux, S.; Macallan, D.C. Identification of proliferative and non-proliferative subpopulations of leukemic cells in CLL. Leukemia 2022, 36, 2233–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.; Coulter, E.; Halliwell, E.; Profitos-Peleja, N.; Walsby, E.; Clark, B.; Phillips, E.H.; Burley, T.A.; Mitchell, S.; Devereux, S.; et al. TLR9 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia identifies a promigratory subpopulation and novel therapeutic target. Blood 2021, 137, 3064–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morande, P.E.; Sivina, M.; Uriepero, A.; Seija, N.; Berca, C.; Fresia, P.; Landoni, A.I.; Di Noia, J.M.; Burger, J.A.; Oppezzo, P. Ibrutinib therapy downregulates AID enzyme and proliferative fractions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2019, 133, 2056–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyach, J.A.; Smucker, K.; Smith, L.L.; Lozanski, A.; Zhong, Y.; Ruppert, A.S.; Lucas, D.; Williams, K.; Zhao, W.; Rassenti, L.; et al. Prolonged lymphocytosis during ibrutinib therapy is associated with distinct molecular characteristics and does not indicate a suboptimal response to therapy. Blood 2014, 123, 1810–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiodin, G.; Drennan, S.; Martino, E.A.; Ondrisova, L.; Henderson, I.; Del Rio, L.; Tracy, I.; D’Avola, A.; Parker, H.; Bonfiglio, S.; et al. High surface IgM levels associate with shorter response to ibrutinib and BTK bypass in patients with CLL. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 5494–5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Wang, S.; Franzen, C.A.; Venkataraman, G.; McClure, R.; Li, L.; Wu, W.; Niu, N.; Sukhanova, M.; Pei, J.; et al. Ibrutinib and venetoclax target distinct subpopulations of CLL cells: Implication for residual disease eradication. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, R.; Slinger, E.; Weller, K.; Geest, C.R.; Beaumont, T.; van Oers, M.H.; Kater, A.P.; Eldering, E. Resistance to ABT-199 induced by microenvironmental signals in chronic lymphocytic leukemia can be counteracted by CD20 antibodies or kinase inhibitors. Haematologica 2015, 100, e302–e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzo, F.; Forestieri, G.; Vit, F.; Ianna, G.; Tissino, E.; Bittolo, T.; Papotti, R.; Gaglio, A.; Terzi di Bergamo, L.; Steffan, A.; et al. Early reappearance of intraclonal proliferative subpopulations in ibrutinib-resistant chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia 2024, 38, 1712–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Friedman, D.; Patten, P.E.M.; Hoogeboom, R. Functional Intraclonal Heterogeneity in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Proliferation vs. Quiescence. Lymphatics 2025, 3, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040047

Friedman D, Patten PEM, Hoogeboom R. Functional Intraclonal Heterogeneity in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Proliferation vs. Quiescence. Lymphatics. 2025; 3(4):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040047

Chicago/Turabian StyleFriedman, Daniel, Piers E. M. Patten, and Robbert Hoogeboom. 2025. "Functional Intraclonal Heterogeneity in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Proliferation vs. Quiescence" Lymphatics 3, no. 4: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040047

APA StyleFriedman, D., Patten, P. E. M., & Hoogeboom, R. (2025). Functional Intraclonal Heterogeneity in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: Proliferation vs. Quiescence. Lymphatics, 3(4), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/lymphatics3040047