Abstract

Debt-for-nature instruments are financial transactions that allow countries to restructure and reduce foreign debt in exchange for investments in environmental conservation measures. Can debt-for-nature instruments attract more capital for biodiversity finance? Debt-for-nature instruments first appeared in the market in the 1980s; however, they have seen a recent surge in popularity, with transactions predominantly focused on marine conservation. These transactions have gained attention for their size, innovative nature, and conservation focus. However, they have also faced criticism surrounding sovereignty, effectiveness, and transaction costs. The descriptive qualitative analysis of a comprehensive and global sample of the eight tripartite type debt-for-nature instruments brought to market since 2015, with a detailed case study of the Belize transaction, indicates that such deals may be costly to negotiate, the use of blue bond labeling can be misleading, conservation benefits are limited, and they have limited replicability. On the positive side, these deals have introduced innovative structures to unlock additional funds for conservation. The best examples are structured with a larger financial commitment to nature and strong enforcement mechanisms. In some cases, the transaction laid the groundwork for future marine conservation funding and commitments. Debt-for-nature instruments are not a silver bullet for either environmental impact or debt refinancing; however, the benefits of recent transactions indicate a role for such innovative instruments in conservation finance.

1. Introduction

Oceans are fundamental to life on earth and critically important in achieving the broad sustainable agenda; they play a role in food systems, global transport, climate stabilization, and local livelihoods [1]. Despite this, ocean health and sustainability are increasingly threatened by human pressures, such as climate change, pollution, and unsustainable fishing. Oceans require urgent investment to curb rising threats; however, the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) that targets their conservation and sustainable use (SDG 14 Life Under Water) remains the most underfunded of any of the SDGs. The World Economic Forum estimates that an investment of USD 175 billion per year is needed to achieve SDG 14 by 2030; yet, between 2015 and 2019, just below USD 10 billion was invested [2].

Among the challenges in mobilizing capital for ocean financing are the high and rising debt burdens faced by many coastal regions and small island developing states. Many developing countries spend more on interest payments than on other public expenditures, and their external public debt makes them vulnerable to currency fluctuations and external shocks [3]. These factors reduce their fiscal space, constrain their spending on climate resilience and adaptation, and limit their progress toward sustainable development. Furthermore, such countries may not be able to access the primary market to fund conservation projects via financing mechanisms such as green or blue bonds due to their credit ratings.

Debt-for-nature instruments emerged in the late 1980s as a tool to both finance conservation and reduce debt burdens. However, they were not applied to marine conservation until 2015, when the Seychelles finalized a debt swap aimed at investing in the Blue Economy. This deal set off a wave of new debt-for-nature instruments, largely focused on marine conservation, which have been larger, more complex, and more innovative than previous transactions. Now a growing but nascent part of the labeled debt market, the market for debt-for-nature could grow to USD 800 billion [4].

In the context of a dramatic decrease in biodiversity and considering its negative impact on the global economy, the private sector can play a material role, in particular corporates and financial institutions. Either because of rising regulatory requirements [5], fiduciary duty [6], or to better manage risk and future opportunities, corporate and financial institutions have dedicated increasing resources to the topic. The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), modeled after the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), was launched in 2021. It published its final disclosure recommendations in September 2023 [7]. The Network for Greening the Financial System, published in 2023, is a framework to help central banks and supervisors identify and assess sources of nature-related transition and physical risks [8].

Even though there is a large and growing stream of literature on sustainable finance, activities linked to climate adaptation and mitigation and transitioning to a low-carbon economy require more research and investments [9]. The link between biodiversity and finance has received even less attention from academics [10]. Biodiversity finance, as an incipient field within sustainable finance, can help define the right financial mechanisms to attract funding for biodiversity with the proper measurement of impact. This paper is an attempt to fill this gap.

The purpose of this paper is (1) to provide the most detailed understanding of debt-for-nature instruments, as well as the background and context for their recent surge in popularity, and (2) to analyze recent transactions based on a comprehensive review of market data and academic research, to better understand the potential role in increasing funding for biodiversity finance and conservation. Analysis of recent transactions includes an overview of recent debt-for-nature instruments, as well as an in-depth case study of one transaction: Belize’s 2021 debt-for-nature instrument.

The article is structured as follows: in Section 2, we provide a detailed and critical description of debt-for-nature instruments. Section 3 provides an overview and analysis of eight recent debt-for-nature transactions, six of which are focused on marine conservation. Section 4 is an in-depth case study of Belize’s 2021 debt-for-nature swap. The article ends with a conclusion.

2. Debt-for-Nature Instruments

2.1. Debt-for-Nature Instruments as a Financial Tool for Debt Relief and Conservation

The financial sector, especially via its asset management and investment banking arms, has led important innovations in instruments, bringing additional capital to projects that present positive contributions to people and the planet. Emerging markets, from island states to large economies such as Brazil, present a strong potential for sustainable finance, even though disclosure remains an issue [11]. Green bonds have been the most popular, but labels have grown, including blue bonds [12], sustainability-linked bonds [13], and social impact bonds [14], among others. The idea of attracting financing to projects that have a positive social or environmental impact is not novel, as evidenced by the rise of the commercial microfinance industry two decades ago and its challenges to secure stable funding sources and measure its positive social impact [15,16]. In that same vein, there is a large and growing stream of research focusing on the relationship between sustainability and performance, as well as an incipient literature on the use of private capital to finance biodiversity conservation and restoration [17,18].

Debt-for-nature instruments have a dual mandate: they are financial transactions that allow countries to restructure and reduce foreign debt in exchange for investments in environmental conservation measures. Debt-for-nature instruments are often referred to as debt-for-nature swaps, considering that debt is restructured or “swapped” for a new debt instrument with more favorable terms. It is important to note that debt-for-nature instruments are not securities, options, or swaps, like credit default swaps or other types of swaps. The word “swap” is, therefore, a misnomer, as those transactions are primarily debt restructurings. However, as markets have adopted this term, we use debt-for-nature swaps or instruments equally in the article.

The goal of debt-for-nature swaps is to free up fiscal resources so that countries can build climate resilience and address conservation issues while still focusing on other development priorities without triggering a fiscal crisis. This is achieved by reducing debt outstanding, lowering interest rates, or extending repayment periods. Debt-for-nature swaps can provide emerging economies with market access, reduced debt burdens, and a pathway to invest in long-term environmental sustainability to safeguard local livelihoods. For some countries, debt-for-nature swaps may provide an attractive alternative to International Monetary Fund (IMF) financing [19].

The effectiveness of debt-for-nature swaps as a tool for both debt relief and conservation can vary greatly from deal to deal, and research analysts have cautioned that investors should apply scrutiny in understanding the merits of each transaction. According to analysts at AllianceBernstein, successful transactions must provide significant debt relief that is redirected toward conservation, as well as satisfactory yield for investors in newly issued bonds [20]. From an ESG perspective, rigorous due diligence should analyze conservation commitments and the viability of underlying nature projects, as well as the credentials of governments involved [20]. Illustrating the need for such diligence, analysts at Barclays recently cited concerns over El Salvador’s debt-for-nature swap given the country’s relatively low biodiversity scores, elevated bond prices, and the government’s proposed 20% cut in its 2025 budget allocation to the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources [21].

2.2. The Mechanics and Stakeholders of Debt-for-Nature Swaps

Debt-for-nature swaps can involve both official bilateral and commercial debt, and there are different kinds of instruments depending on the parties involved and the sources of funding [22]. Common structures include bilateral and multilateral swaps, which are negotiated directly with one or more official creditors, as well as tripartite swaps, which are financed by a non-governmental organization (NGO) that buys back privately held debt [23]. Tripartite swaps involve three key parties: a debtor, creditors, and an NGO. Additional stakeholders may also be involved, such as market investors, investment banks, and development banks; in such cases, the transaction may be referred to as a “tripartite plus” swap [22]. This paper will focus on tripartite-type swaps.

A basic tripartite debt-for-nature swap works as follows: (1) an NGO lends to the debtor country at a below-market rate, (2) those funds are used to repurchase existing debt at a discount, and (3) the country commits to use a portion of the resulting debt relief to fund conservation measures [22].

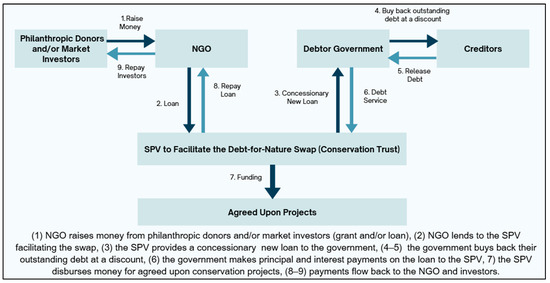

A special purpose vehicle (SPV) is established to facilitate the swap; it acts as a bridge between the NGO and the debtor country and can disburse funds for agreed-upon conservation projects. In a tripartite plus swap, the swap may involve investment banks raising capital from market investors to facilitate the new loan. Development banks may also be involved in providing insurance on the new loan to de-risk the loan and lower the cost of borrowing. Figure 1 below illustrates the structure of a typical tripartite swap.

Figure 1.

Tripartite debt-for-nature swap. Source: Authors, adapted from IMF [22].

2.3. The History of Debt-for-Nature Swaps

Debt-for-nature swaps emerged in the 1980s as a response to the Latin American debt crisis, during which many countries found themselves unable to repay large foreign loans. The first debt-for-nature swap occurred in 1987 between Bolivia and Conservation International, a U.S.-based non-profit. It was a tripartite swap in which Conservation International used USD 100,000 in philanthropic funding to purchase USD 650,000 of Bolivia’s external debt from the secondary market at 15 cents on the dollar [24]. This debt was subsequently forgiven, and in exchange, the Bolivian government set aside 3.7 million acres in the Amazon Basin for conservation purposes [24]. Under the terms of the swap, the Bolivian government also agreed to create a conservation fund in local currency worth USD 250,000 to manage land for sustainable uses [25]. Administration of the fund was managed by the Bolivian Ministry of Agriculture, as well as the Bolivian NGO designated by Conservation International.

Criticisms of early debt-for-nature swap transactions included concerns about sovereignty infringement. In the 1987 Bolivia swap, for example, Conservation International did not consult the 25,000 Tsimané people living in and around one of the forest reserves in question. New environmental programs established under the swap described Indigenous activities as detrimental to forest preservation, prompting Indigenous populations to accuse Conservation International of interfering with Bolivia’s right to control its land [26].

Despite such criticisms, debt-for-nature swap transactions grew in popularity in the following years. Since the first instrument in 1987, there have been close to 150 debt-for-nature swaps, with most occurring in the 1990s [27]. Transactions declined in the 2000s; among factors contributing to this decline may have been the shift to more comprehensive debt relief under initiatives such as the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative [28]. To date, more than half of debt-for-nature swap transactions have been bilateral swaps, and the average transaction size was USD 26.6 million [27].

2.4. A New Wave of Debt-for-Nature Swaps

Recently, debt-for-nature transactions have experienced a surge in popularity, with a wave of new deals that are larger, more complex, and increasingly innovative. These transactions have largely focused on marine conservation, and they began with a tripartite debt-for-nature swap closed by the Seychelles in 2015.

The Seychelles swap differed from previous transactions in two key ways: (1) it was the first swap specifically focused on marine conservation and climate adaptation, and (2) it introduced impact investors as the source of funds for repurchasing prior debt [29]. The NGO supporting the transaction was The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a U.S.-based conservation organization that works in over 70 countries to conserve critical lands and waters. TNC established the Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust (SeyCCAT) to facilitate the swap and raise loan capital from impact investors, as well as grant funding from philanthropic foundations, to finance the swap. While Seychelles is known for issuing the market’s first “blue bond,” this occurred after the debt-for-nature swap transaction in 2018. The proceeds of the blue bond expanded upon the marine conservation commitments made under the swap, and USD 3 million of blue bond proceeds are managed by SeyCCAT, the conservation trust established under the swap [30].

The Seychelles swap transaction acted as a proof of concept and laid the groundwork for what was initially called TNC’s “Blue Bonds for Conservation Model”. Under this model, TNC was seeking to increase the world’s marine protected areas by up to 15% within a decade through debt-for-nature swaps [31]. Key to the model was the creation of new financial flows for marine conservation, to be generated through debt conversions financed by blue bonds sold to market investors. The model also involved a multi-year process of stakeholder engagement, marine spatial planning, and policy reforms to ensure the long-term sustainability of protected areas [31]. TNC has since rebranded the model as the “Nature Bonds Program,” an expansion to include freshwater and terrestrial outcomes. In total, TNC has supported six conservation debt-for-nature swap transactions. Two other NGOs, Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project and Catholic Relief Services, have applied the model in one transaction each.

Building on TNC’s work, at the 2024 UN Biodiversity Conference, six global environmental NGOs, including TNC, Pew Charitable Trusts, Conservation International, Re:wild, The Wildlife Conservation Society, and World Wildlife Fund, announced the formation of a Coalition to scale conservation and climate outcomes through the use of debt-for-nature swap instruments [32]. The Coalition will focus on creating practice standards for debt-for-nature swaps, developing a shared pipeline of potential projects, working to expand capital available for credit enhancement, coordinating policy efforts, and sharing knowledge and best practices [32]. The Coalition estimates that debt-for-nature swaps have the potential to unlock up to USD 100 billion in climate and nature finance.

Beyond TNC’s Nature Bonds Program and the recently formed Coalition, other factors contributing to the recent surge in debt-for-nature swap transactions include growing global debt burdens, higher inflation, and high interest rates. Many developing countries had significant debt burdens before the pandemic and have reached unsustainable debt levels. Thirty-four of the fifty-nine emerging economies that are most vulnerable to climate change are also at high risk of fiscal crises [33]. Such unsustainable debt trajectories require debt restructurings, such as those provided by debt-for-nature swaps.

3. Overview of Recent Debt-for-Nature Swaps

3.1. Summary and Analysis of Recent Transactions

Table 1 summarizes the full list of tripartite debt-for-nature swaps brought to market since 2015 that fall under TNC’s Nature Bonds model, meaning those that have been structured to broaden market participation and unlock additional capital. Not included in our analysis are bilateral or non-marketed debt-for-nature swaps. The 2024 agreement between the U.S. and Indonesia is an example of the types of debt-for-nature swaps excluded from our analysis; while this swap involved the participation and contribution of funds from four NGOs, the agreement was largely between the U.S. and Indonesia and did not seek broader market participation [34].

Table 1.

Debt-for-nature transactions.

Of the eight transactions, six have focused on marine conservation. The El Salvador transaction funded freshwater projects for the Rio Lampa, and the 2024 Ecuador transaction funded projects to protect the forests and wetlands of the Amazon. This section will analyze these transactions, in particular, the deal structure and use of labeled bonds, use of insurance and/or credit enhancements, credit ratings, debt reduction, conservation funding, and feasibility.

3.1.1. Deal Structure and Use of Labeled Bonds

All the deals in the table are tripartite swaps supported by an NGO. TNC served as the NGO partner in six transactions; Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy Project and Catholic Relief Services served as the NGO partner in one transaction each.

The Seychelles swap acted as a pilot for TNC’s “Blue Bonds for Conservation Model”. This transaction was smaller and did not utilize a large investment bank to raise funds from market investors via blue bonds. In fact, NatureVest, TNC’s in-house impact investment unit, raised USD 15 million in loan capital from impact investors and USD 5 million in grant funding from philanthropic foundations to finance the swap.

Subsequent debt-for-nature swap transactions (Belize, Barbados, Gabon, and both Ecuador transactions) expanded upon the success of the Seychelles swap by using investment banks to access market investors via newly issued bonds. These deals were much larger in size, with newly issued bonds ranging from USD 147 million to USD 1 billion and retired debt ranging from USD 151 million to USD 1.628 billion. The newly issued bonds sold to investors were labeled; in three transactions, bonds were labeled as “blue,” in one transaction, bonds were labeled as “marine conservation linked,” and in one transaction, bonds were labeled for the conservation project as “Biocorredor Amazonico” bonds. Two transactions (Bahamas and El Salvador) were structured as loans. In all cases, the majority of funds were used to repurchase outstanding debt obligations.

3.1.2. Insurance, Credit Enhancements, and Credit Ratings

Key to selling the large, labeled bond issuances to market investors was the use of insurance and credit enhancements. An analysis by Clifford Change highlights that credit guarantees are commonly used products in blended finance and are generally familiar to investors in this space. Political risk insurance adds complexity to transactions as payouts occur only after the SPV involved in a transaction obtains an arbitral award against the sovereign following a default. As such, political risk insurance generally requires a liquidity facility to cover interim debt service [38].

Following the Seychelles swap, all transactions used political risk insurance, a credit guarantee, or both. U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) provided political risk insurance for the Belize, Gabon, El Salvador, and both Ecuador transactions. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) provided partial credit guarantees for the Barbados, Bahamas, and both Ecuador transactions. For the Barbados transaction, IDB provided a co-guarantee with TNC, resulting in two classes of bonds. The Bahamas transaction introduced a private insurer for credit insurance, as well as a private impact investor providing a co-guarantee alongside IDB. Two transactions also used parametric catastrophe insurance to cover debt payments in the event of hurricanes. Despite sub-investment grade ratings held by debtor countries, the bonds issued to finance the swaps were able to secure investment grade ratings due to the use of these credit enhancements; all new bonds were rated Aa2 or better. Credit enhancements de-risked the transactions, which was critical in attracting investors, lowering the cost of borrowing, and generating sufficient savings to redirect funds toward conservation projects. Structuring deals to incorporate the creditworthiness of development banks effectively granted high-yield debtor countries access to the investment-grade market and lower-cost loans, unlocking new pools of capital for conservation.

The table below (Table 2) shows the debtor countries’ Moody’s ratings when the debt-for-nature swap transactions closed. While Moody’s did not downgrade any countries as a result of the swaps, downgrade risk should be considered in debt-for-nature swaps, as some transactions may be considered events of default. According to Moody’s definition, in addition to a financial loss for creditors, if a buyback helps a debtor country avoid a likely default, the transaction is deemed a distressed exchange and, therefore, an event of default [39]. For the recent transactions, Moody’s considered the Belize and both Ecuador swaps to be events of default but did not downgrade the ratings.

Table 2.

Insurance, credit enhancements, and ratings.

3.1.3. Debt Reduction

The ratio of debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) measures how much a country owes compared to how much it produces. This ratio can indicate whether a country’s debt burden is sustainable, as well as its ability to repay its debts. As illustrated in Table 3 below, the impact of the swap transactions on immediate debt reduction as a percentage of GDP ranged from 0.1% to 8.7%. For three transactions, there was no immediate reduction in principal outstanding. For these transactions, savings were generated by discounted repurchase prices, as well as debt service savings over the life of the bonds. For five transactions, the immediate debt reduction was less than 1% of GDP. The only exception was Belize, with an 8.7% reduction. However, Belize’s debt remained elevated. The magnitude of the impact varied based on the specifics of the swap transactions, such as the repurchase price, as well as the debt profile of the debtor country.

Table 3.

Debt reduction.

3.1.4. Conservation Funding

Funds for conservation are a key component of debt-for-nature swap transactions. Conservation funding commitments in all recent transactions have included two components: (1) annual payments to newly established conservation funds that will be disbursed over time for conservation projects and (2) funding for endowments that will be invested until maturity to ensure that funds are available to finance conservation beyond the term of the transaction.

The table below (Table 4) summarizes conservation funding commitments in each transaction. Endowments have either been funded by annual payments or pre-funded with a lump sum. In either case, funds are invested until maturity. Total estimated funds for conservation, as stated in transaction documents and case studies by the NGOs, include the sum of all annual conservation contributions and the future value of endowment funds using an assumed rate of return. In the Belize transaction, for example, TNC assumes a 7% annual return on the endowment funds, resulting in an ending endowment value of approximately USD 90 million. This, plus USD 4.2 million per year over 20 years, is how TNC estimated funds for marine conservation of approximately USD 178 million. As of the most recent Impact Report (31 March 2023), the value of Belize’s endowment fund had declined to just below USD 20 million due to negative performance inception-to-date [42]. This highlights the risk of using an assumed rate of return and emphasizes that stated funds for conservation are not guaranteed and may be less than estimated.

Table 4.

Conservation funding.

3.1.5. Feasibility

The feasibility of debt-for-nature swaps requires that new bonds be able to attract sufficient investors while still providing debtor countries with sufficient debt relief to make the financial metrics of the swap work. Rate volatility, political unrest, and other risk factors may test investor appetite for such transactions.

The complexity of these transactions may also prohibit wide-spread replication and limit feasibility. These transactions have been replicable to an extent, as demonstrated by the wave of transactions that have closed in recent years. However, while these transactions have all followed a similar model, they have also depended on many factors that vary by country.

Factors that explained the success of the Belize swap included TNC’s long history of conservation work in Belize, the country’s favorable political situation, the link between conservation and local income, and the fact that Belize had only one foreign currency bond outstanding at the time [44]. These factors were unique to Belize and critical to the feasibility of the swap. The alignment of such country-specific factors may limit the replicability of debt-for-nature swaps in other countries.

Based on our analysis of recent transactions, as well as an analysis by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) regarding the potential application of debt-for-nature swaps in Asia-Pacific developing economies, below (Table 5), we summarize factors that contribute to the feasibility of a debt-for-nature swap transaction, as well as obstacles [45]. Feasibility requires the alignment of many specific factors beyond the above-mentioned country-specific factors.

Table 5.

Feasibility.

3.2. Differences Between Recent Transactions and Prior Swaps

Compared to historical transactions, the Seychelles debt-for-nature swap introduced marine conservation as the focus of the swap, and it introduced impact investors as the source of funds for refinancing. The subsequent transactions expanded on the success and structure of the Seychelles swap, resulting in a string of transactions that are more complex, innovative, and larger than those of the past.

More than half of historical swap transactions were bilateral [27]. The recent wave of debt-for-nature swap transactions have been tripartite, and beyond involving an NGO, they have involved development banks, insurers, investment banks, and market investors, among other stakeholders. The complexity of these recent transactions contributes to their lengthy preparation periods and high costs. Their complex, contractual structures have also established credible, concrete, and enforceable conservation commitments, turning them into more robust instruments for biodiversity finance.

Recent swaps have utilized political risk insurance and credit guarantees from development banks, as well as parametric catastrophe insurance. These credit enhancements have facilitated investment-grade ratings from rating agencies, effectively granting non-investment-grade debtor countries access to the investment-grade market. This has expanded the investor pool and lowered the cost of borrowing on bonds sold to investors. This was critical in generating the debt service savings needed to finance conservation commitments.

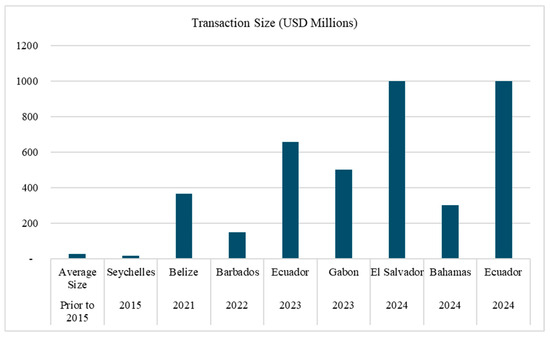

Historically, the average size of debt-for-nature swaps was USD 26.6 million [27]. As illustrated in the chart below (Figure 2), recent swaps are far larger, thanks to the use of credit enhancements and investment banks to access investment-grade market investors. This has unlocked a new pool of funds for conservation.

Figure 2.

Transaction size. Source: Authors, adapted from IMF, TNC, Pew, Bloomberg.

3.3. Controversies and Challenges Surrounding Recent Transactions

Recent transactions have attracted sufficient market investors to facilitate the swaps; however, there have been negative headlines on recent transactions. These have largely focused on pricing and debt service savings, labeling of newly issued bonds, uncertainty surrounding political unrest in debtor countries, and opposition to sovereignty infringement and a lack of transparency.

3.3.1. Pricing and Debt Service Savings

Gabon’s deal faced criticisms surrounding pricing and debt service savings. The structuring investment bank delayed the transaction due to broader market volatility and subsequently needed to increase the yield on the blue bonds to garner enough investor interest [46]. The blue bonds maturing in 2038 ultimately priced at 200 basis points over the 10-year Treasury at a yield of 6.097%, up from initial price talk of 180 basis points [46]. This is the yield paid to investors and does not include the cost of political risk insurance. Including the cost of insurance could take the overall cost closer to 7.50%, negating many benefits of the structure since the average coupon on the bonds subject to the tender offer was nearly 7% [47].

3.3.2. Labeling

Three of the transactions used the blue bond label on bonds sold to investors to facilitate the swaps, even though the majority of funds were used to buy back existing debt, with a small portion allocated to conservation. Allocation and lack of transparency sometimes led to criticism, in line with what is observed in the labelled bond market [48]. The bonds were sold before the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) issued blue labeling guidelines in September 2023. In this guidance, ICMA recognizes blue bonds as a subset of green bonds, which it defines as “any type of bond instrument where the proceeds […] will be exclusively applied to finance or refinance, in part or in full, new and/or existing eligible Green Projects” [49]. The previously issued blue bonds do not align with this definition, and they were subsequently reclassified by certain fund managers. Nuveen, for example, reclassified the bonds as “environmentally focused” [50]. Similarly, TNC has since issued a statement that it will use the label of “nature bonds” rather than blue bonds moving forward.

3.3.3. Political Implications

Just two weeks after Gabon’s USD 500 million debt-for-nature swaps closed, the nation experienced a coup that left investors unsure about the impact on their investments. The newly issued blue bonds received an Aa2 rating from Moody’s and attracted investment-grade investors, despite Gabon’s sub-investment-grade rating, due to the political risk insurance provided by DFC. This insurance benefits from the full faith and credit of the United States and protects bondholders from governmental default on underlying loans by covering 100% of an arbitration award; it does not provide a guarantee of timely payment [51]. However, such contracts have not yet been activated in a debt-for-nature swap [52]. Situations of political unrest may act as a reminder for investors that “countries with poor economic or political fundamentals, or with a history of distress, may not necessarily make the best counterparts for long-term environmental commitments” [52].

3.3.4. Transparency Challenges

In December 2022, more than 30 non-profits, including Greenpeace and the Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements, signed a joint statement calling for the rejection of debt-for-nature swaps due to their lack of transparency, as well as the undue power they give to foreign organizations over marine management policies in developing and small island states [53]. Echoing the criticism discussed of the first ever debt-for-nature swap, the statement criticizes debt-for-nature swaps for not achieving informed consent of citizens affected, as well as for preventing public understanding of actual achievements. It argues that such swaps do not free up funds for urgent development priorities, such as health or education, and that they bestow power to a single conservation organization solely based on its ability to raise funds through the capital markets [53].

4. Case Study: Belize

Recent debt-for-nature swaps have been complex transactions involving many stakeholders and commitments. To better understand the intricacies of such transactions, as well as their scalability and impact, this paper will analyze one case in greater detail. The Seychelles swap acted as a test case for TNC. The subsequent transaction, Belize’s USD 364 million debt-for-nature swap, was larger and expanded on the structure of the Seychelles swap by utilizing an investment bank to raise market capital via blue bonds. The Belize transaction also utilized insurance provided by a development bank to secure an investment grade rating on the blue bonds and lower the cost of borrowing. The transactions that followed were modeled similarly to the Belize deal. As such, this paper will review the Belize case in detail.

4.1. Transaction

Belize undertook a debt-for-nature swap in 2021. At the time, the country had recently restructured or defaulted on its debt four times in ten years. Prior to the 2021 swap, Belize was rated Caa3 by Moody’s and selective default by S&P, with limited access to external financing, according to the IMF [44]. Belize had one series of foreign currency bonds outstanding, a USD 553 million USD bond due in 2034 known as the “Superbond” [44]. As the COVID-19 pandemic pushed Belize’s economy into recession, the price of these bonds plummeted to a deep discount. Simultaneously, the nation’s debt-to-GDP ratio increased by 24 percentage points in 2020 to levels deemed unsustainable [44]. This prompted authorities to pursue ambitious fiscal consolidation, as well as debt restructuring in the form of a debt-for-nature swap.

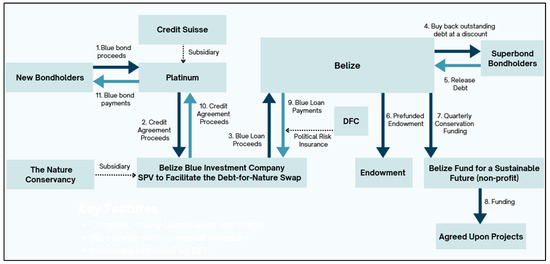

Diagram 2 below illustrates the debt conversion involved in the Belize swap, which is composed of a series of back-to-back financial transactions. Two subsidiaries were formed to facilitate the swap: Platinum Securities Cayman SPC Limited (“Platinum”) and the Belize Blue Investment Company (BZBIC). Platinum issued a USD 364 million blue bond to the market, the proceeds of which were then lent by Platinum to BZBIC. BZBIC, in turn, provided a blue loan to the government of Belize, most of which was used to buy out Superbond bondholders. Some funds were allocated to a pre-funded endowment. Belize makes interest and principal payments on the blue loan to BZBIC; these payments then flow to Platinum to make interest and principal payments on the blue bonds to market investors.

In September 2021, Belize offered to buy the Superbond back for cash (Figure 3); 87% of existing bondholders agreed to receive 55 cents for each dollar of face value held [44]. This surpassed the consent threshold for the bond’s collective action clause, which allowed Belize to redeem remaining bonds for 52 cents on the dollar. In November 2021, Belize settled the cash tender offer, paying USD 301 million using proceeds from the blue loan (financed by proceeds from the blue bond) and canceling all of the outstanding Superbonds [44].

Figure 3.

Belize debt-for-nature swap. Source: Adapted from TNC and Capital Markets Law Journal [44].

The blue loan between BZBIC and the government of Belize amounted to USD 364 million. Of that, USD 301 million was used to retire the USD 553 million Superbond at 55 cents on the dollar, USD 24 million pre-funded an endowment for the Conservation Fund, and USD 39 million funded liquidity reserves, transaction costs, and the original issue discount [54]. The loan reduced Belize’s public debt stock by USD 216 million or 8.7% of GDP in 2021; this included USD 189 million in principle, as well as the USD 27 million Superbond coupon payment due in 2021 [44].

The blue loan also extended the maturity of Belize’s debt by over six years. The blue loan has a maturity of 20 years, with a 10-year grace period of principal repayments before the principal amortizes for the remaining life of the loan [44]. The blue loan has a stepped coupon schedule that began at 3% in 2022 and gradually increased to 6% by 2026. Comparatively, the Superbond carried an interest rate of 6.77% [44].

Insurance was a key element of the transaction; the deal utilized political risk insurance, as well as parametric catastrophic insurance. Political risk insurance was provided by DFC and covers Belize’s payment of the blue loan to BZBIC, thereby indirectly protecting blue bondholders against non-payment by Belize. According to an analysis by the IMF, the deal would not have been possible without the DFC credit enhancement [44]. The enhancement facilitated an investment grade Aa2 rating by Moody’s on the blue bonds, effectively allowing Belize access to the investment grade market. This increased the potential investor pool and lowered the cost of borrowing. The transaction also utilized catastrophe insurance, which provides coverage for blue loan debt payments following an eligible hurricane event in Belize.

As part of the transaction, Belize entered into the Conservation Funding Agreement, a 20-year agreement between Belize and TNC that lays out the nation’s conservation funding commitments, as well as pre-defined ocean conservation milestones. Under the agreement, Belize will pay an average of USD 4.2 million equivalent in local currency per year to the Conservation Fund. The Conservation Fund disburses money as grants to government agencies, NGOs, and local businesses working on marine conservation and blue economy projects. The Conservation Funding Agreement more than triples Belize’s pre-transaction budget for marine conservation [54].

In addition to increasing funding for conservation and defining milestones, the Conservation Funding Agreement also includes provisions in the event that conservation milestones are not met. In such a case, Belize’s annual conservation payment will increase by USD 1.25 million per year for the first missed milestone and an additional USD 250,000 for each subsequently missed milestone [54]. The Conservation Funding Agreement also has a cross-default provision with the blue loan, meaning that if Belize does not meet its payment funding obligations, both the Conservation Funding Agreement and the blue loan will enter into default [54].

4.2. Conservation Commitments

Conservation commitments were a critical element of the Belize transaction. The DFC credit enhancement, which enabled the new blue bond issuance, would not have been provided without credible and concrete commitments to marine conservation. Belize made contractual pledges that are to be assisted and monitored by TNC, which has been involved in conservation efforts in Belize for more than three decades and has established its credibility and expertise as a conservation organization [44].

Belize has committed to key milestones, which are time-bound. Conservation commitments include the following: an increase in biodiversity protection zones from 16% to 30% of ocean area by 2026; protection of public lands within the Belize Barrier Reef System as mangrove reserves; completion of a Marine Spatial Plan by 2026; inclusion of marine and coastal biodiversity offsets in Belize’s Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan; application for three formally designated marine protected areas as International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Green List Areas; and other non-legally binding conservation commitments, such as a governance framework for domestic and high seas fisheries [54]. Key milestones, their deadlines, and current progress are included in Appendix A.

A key component of Belize’s conservation commitments is the marine spatial plan, which will determine where to expand ocean protection and management to reach the 30% commitment. This will be facilitated by TNC and will involve stakeholders such as local communities, tourism businesses, fishing associations, and government officials [54]. TNC partners with these local stakeholders to identify activities that contribute to both conservation and sustainable economic development, such as restoring coral reefs for tourism [31]. The government of Belize and TNC successfully began this process in late 2022.

The Conservation Fund, named the Belize Fund for a Sustainable Future (BFSF), is responsible for disbursing funds generated through the Conservation Funding Agreement to in-country partners working on projects aligned with the conservation commitments. Established with the help of TNC, the fund is now operational. Payments made by Belize as required under the Conservation Funding Agreement are paid mostly in Belizean dollars, and the fund has an independent board of nine directors appointed from government and non-government sectors [54]. As of the most recent Impact Report (31 March 2023), BFSF has allocated approximately USD 7.6 million (in BZD equivalent) in grant funding [42].

4.3. Benefits of the Transaction

The transaction reduced Belize’s external public debt stock by USD 216 million, or 8.7% of GDP, and extended maturity by over six years. According to TNC, Belize will save USD 53.6 million in debt service during the first five years and USD 200 million over the 20-year life of the blue loan. Additionally, while Belize replaced some existing debt service obligations with marine conservation commitments under the swap, these payments are to be made in local currency. This reduces the strain on the nation’s international reserves and increases investment in the local economy [44].

The establishment of the Conservation Fund and its pre-funded endowment will ensure that funds are available to finance marine conservation after the Conservation Fund Agreement expires in 2041. Additionally, Belize’s climate commitments under the swap are based on a contractual structure and are backed by legally enforceable and financially meaningful consequences [44]. For example, failure to make the annual payment to the Conservation Fund would trigger an acceleration of Conservation Fund payments, a cross-default with the blue loan, as well as an acceleration of the blue loan, with accrued interest and full principal to be due immediately [44]. This contractual structure of the Belize swap provides more robust enforcement mechanisms than other sovereign green finance instruments, such as the use of proceeds bonds and sustainability-linked bonds. The use of proceeds bonds does not provide bondholders with actionable rights to enforce “green” or “social” elements of the bond, which means failure by an issuer to allocate proceeds as described in the offering documents does not constitute a mandatory event of default [44].

The transaction created an independent Conservation Fund to manage conservation funding; this ensures that conservation funds are kept separate and will be applied toward conservation. The fund is managed by a board, to which Belize is able to appoint directors; however, the board is an independent legal entity with majority non-government representation. Non-governmental board stakeholders include individuals from civil society, academia, and the private sector. Additionally, TNC, which has extensive conservation experience, including in Belize, is involved in guiding and monitoring Belize’s performance toward key milestones, as well as developing the marine spatial plan [44].

4.4. Challenges and Criticisms of the Transaction

While Belize’s level of outstanding debt did improve after the swap, complemented by sizable fiscal consolidation, the nation’s public debt remained elevated. In May 2022, the IMF assessed Belize’s public debt as unsustainable in the absence of additional measures [55].

The transaction’s complex structure strengthens the conservation elements of the swap compared to other sovereign green finance instruments. However, it also requires the involvement of many sophisticated stakeholders, as well as the creation of interconnected subsidiaries and trusts. This complexity limits the scalability and replicability of the Belize transaction and also increases its cost relative to other financial mechanisms. Additionally, while external stakeholders bring credibility and expertise, their involvement in the structure reduces Belize’s control over its conservation strategy [44]. The total cost of the transaction was not disclosed.

The Belize transaction, as well as all the other recent transactions, have utilized USD-denominated debt. International institutional investors that have been driving demand generally invest in hard currency, which minimizes volatility for investors. For debtor countries, however, this introduces an additional layer of repayment risk.

5. Conclusions

While debt-for-nature instruments have been utilized since the late 1980s, the transaction closed by Seychelles in 2015 set off a new wave of tripartite transactions. These instruments differ from previous transactions in that they have largely (1) focused specifically on marine conservation and (2) used market investors to finance the restructuring. Key to accessing these investors has been the use of credit enhancements provided by development banks to secure investment-grade ratings. The result has been swaps that are larger, more innovative, and more complex than those of the past.

Recent debt-for-nature instruments have been highly complex transactions involving lengthy negotiations among many stakeholders. This complexity has contributed to higher costs, a key criticism of recent transactions. Furthermore, the complexity of these deals may prohibit wide-spread replication and limit feasibility. Moreover, the impact on sovereign credit ratings should be considered. Depending on the conditions of the swap, the swap may be considered an event of default and may put the debtor country at risk for downgrade, which might increase future borrowing costs. Among the recent transactions, Moody’s considered the Belize and both Ecuador swaps to be events of default but did not downgrade the debtor countries’ credit ratings in these cases.

Debt-for-nature instruments aim to reduce debt and increase conservation efforts. Analysis of recent transactions indicates that both of these outcomes may be somewhat limited in the recent wave of tripartite debt-for-nature swaps. Regarding debt relief, immediate debt reduction as a percentage of GDP has been less than 1% in most transactions. The only exception was Belize, where the debt reduction was 8.7% of GDP; however, the country’s debt remained elevated after the swap. Regarding conservation funding, analysis indicates that conservation funding was limited. Reported numbers are based on total funding over many years and incorporate future endowment values based on assumed rates of return. Additionally, the “blue” label has been considered inadequate as the majority of funds raised are used to repurchase outstanding debt.

Nevertheless, partial restructurings may still have benefits for conservation and debt profiles, as they (1) have introduced innovative structures to unlock larger amounts for conservation, (2) are structured with stronger enforcement mechanisms for conservation finance, and (3) in the case of Seychelles, the transaction laid the groundwork for future conservation funding and commitments. The size of recent debt-for-nature swap transactions illustrates how innovative structures utilizing credit enhancements can broaden the market of potential investors and mobilize capital for conservation and climate resilience. The model used in recent debt-for-nature swaps has successfully tapped the creditworthiness of multilateral development banks to secure investment grade ratings on newly issued bonds, lower the cost of borrowing, and attract investors. Additionally, recent swaps have included cross-default provisions and financial penalties for failing to meet key conservation milestones or financial conservation commitments. By structuring deals so that conservation commitments are backed by legally enforceable and financially meaningful consequences, these transactions can be more effective than more traditional use-of-proceeds bonds and sustainability-linked bonds. Finally, in the case of Seychelles, certain features of the debt-for-nature swap provided the necessary infrastructure to attract additional funding in the subsequent blue bond issuance. The blue bond transaction expanded upon conservation commitments made under the debt-for-nature swap, and SeyCCAT, the trust established under the debt-for-nature swap, was used to manage blue bond funds. This illustrates how debt-for-nature swaps can lay the foundation for future conservation funding and commitments by establishing the necessary policies, conditions, and vehicles.

While debt-for-nature swaps are not a panacea for either environmental or debt crises, the benefits observed in recent transactions suggest a role for debt-for-nature swaps in unlocking funds for conservation finance and provide important lessons for structuring future conservation finance instruments. At present, deals require scrutiny to assess the financial merits of each transaction, as well as due diligence to understand the conservation commitments and credentials of sovereigns involved. Improved transparency, including around transaction costs and impact reporting, could further strengthen the merits of these deals in the eyes of market participants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.O., F.d.M.; methodology, L.O., F.d.M.; validation, F.d.M.; formal analysis, L.O.; writing—original draft preparation, L.O.; writing—review and editing, L.O., F.d.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Belize conservation commitments, due dates, and progress.

Table A1.

Belize conservation commitments, due dates, and progress.

| Milestone | Description | Due Date | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Expand Biodiversity Protection Zones to 20.5% of Belize’s Ocean | 5 April 2022 | Complete |

| 2 | Designate Public Lands within the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System as Mangrove Reserves | 5 April 2022 | Complete |

| 3 | Initiate the process of the developing a Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) for Belize’s Ocean | 11 April 2022 | Complete |

| 4 | Expand Biodiversity Protection Zones to 25% of Belize’s Ocean | 11 April 2024 | Complete |

| 5 | Approve, sign into law, and gazette the revised Coastal Zone Management Act and Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan | 11 April 2025 | |

| 6 | Expand Biodiversity Protection Zones up to 30% of Belize’s Ocean; MSP completed, approved, signed into law, gazetted and implemented | 11 April 2026 | |

| 7 | Apply to have at least 3 designated marine protected areas in Belize listed as IUCN Green List Areas | 11 April 2027 | |

| 8 | Approve Management Plans for the Biodiversity Protection Zones | 11 April 2029 |

Source: Authors, adapted from TNC [42]. To achieve Milestone 4, the government of Belize approved the proposed expansion of Belize’s Total Ocean Space and the designation of its Biodiversity Protection Zones [56]. However, some fishermen have raised concerns about the rapid implementation, as well as transparency, accuracy of resource data, and impact on fishers’ livelihoods [57].

References

- World Economic Forum. Climate Finance: What Are Debt-for-Nature Swaps and How Can They Help Countries? 26 April 2024. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2024/04/climate-finance-debt-nature-swap/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- World Economic Forum. SDG14 Financing Landscape Scan: Tracking Funds to Realize Sustainable Outcomes for the Ocean. 27 June 2022. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Tracking_Investment_in_and_Progress_Toward_SDG14.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- UN Global Crisis Response Group. A World of Debt: A Growing Burden to Global Prosperity. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 12 July 2023. Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/world-debt-2023 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Marsh, A. Barclays Joins Citi, HSBC in Chasing Deals in Complex Debt Swaps. 15 September 2023. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-15/barclays-joins-citi-hsbc-in-chasing-deals-in-complex-debt-swaps (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Redondo Alamillos, R.; De Mariz, F. How Can European Regulation on ESG Impact Business Globally? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mariz, F.; Aristizábal, L.; Andrade Álvarez, D. Fiduciary duty for directors and managers in the light of anti-ESG sentiment: An analysis of Delaware Law. Appl. Econ. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TNFD. Recommendations of the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures. Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures (TNFD). September 2023. Available online: https://tnfd.global/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Recommendations-of-the-Taskforce-on-Nature-related-Financial-Disclosures.pdf?v=1734112245 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- NGFS. Nature-Related Financial Risks: A Conceptual Framework to Guide Action by Central Banks and Supervisors. Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). Available online: https://www.ngfs.net/system/files/import/ngfs/medias/documents/ngfs-conceptual-framework-nature-risks.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Deschryver, P.; de Mariz, F. The Role of Transition Finance Instruments in Bridging the Climate Finance Gap. In Global Handbook of Impact Investing: Solving Global Problems Via Smarter Capital Markets Towards a More Sustainable Society; De Morais Sarmento, E., Herm, R.P., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382457152_The_Role_of_Transition_Finance_Instruments_in_Bridging_the_Climate_Finance_Gap (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Karolyi, G.A.; Tobin-de la Puente, J. Biodiversity Finance a Call for Research into Financing Nature. Financ. Manag. 2023, 52, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mariz, F. The Promise of Sustainable Finance: Lessons from Brazil. Georget. J. Int. Aff. 2022, 23, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosmans, P.; de Mariz, F. The blue bond market: A catalyst for ocean and water financing. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2023, 16, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mariz, F.; Bosmans, P.; Leal, D.; Bisaria, S. Reforming Sustainability-Linked Bonds by Strengthening Investor Trust. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mariz, F.; Savoia, J.R.F. Financial Innovation with a Social Purpose: The Growth of Social Impact Bonds. In Research Handbook of Investing in the Triple Bottom Line; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 292–313. [Google Scholar]

- de Mariz, F.; Reille, X.; Rozas, D. Discovering Limits. Global Microfinance Valuation Survey 2011. Global Microfinance Equity Valuation Survey, Washington D.C. 2011. Available at de Mariz, Frederic and Reille, Xavier and Rozas, Daniel, Discovering Limits. Global Microfinance Valuation Survey 2011 (14 July 2011). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2654041 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Glisovic, J.; González, H.; Saltuk, Y.; de Mariz, F.R. Volume Growth and Valuation Contraction Global Microfinance Equity Valuation Survey 2012. Global Microfinance Equity Valuation Survey, Washington D.C. 2012. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2625221 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Possebon, E.A.G.; Cippiciani, F.A.; Savoia, J.R.F.; de Mariz, F. ESG Scores and Performance in Brazilian Public Companies. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Giroux, T.; Heal, G.M. Biodiversity Finance. J. Financ. Econ. 2025, 164, 103987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N. Wall Street’s New ESG Money-Maker Promises Nature Conservation—With a Catch. 11 January 2023. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-01-12/bankers-bet-millions-on-sovereign-debt-deals-tied-to-green-goals (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Rosner, S.; O’Connell, P. Natural Selection: Evaluating Debt-for-Nature Swaps. AllianceBernstein Insights—ESG in Action. 11 January 2024. Available online: https://www.alliancebernstein.com/apac/en/institutions/insights/esg-in-action/natural-selection-evaluating-debt-for-nature-swaps.html (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- White, N. JPMorgan-El Salvador Swap Needs Scrutiny, Barclays Analysts Say. 22 October 2024. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-10-22/barclays-analysts-say-jpmorgan-el-salvador-swap-needs-scrutiny (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Chamon, M.M.; Klok, E.; Thakoor, M.V.V.; Zettelmeyer, M.J. Debt-for-Climate Swaps: Analysis, Design, and Implementation. 12 August 2022. Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2022/162/article-A001-en.xml (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Claeson, M.R. Debt-for-Nature Swaps: A Concise Guide for Investors. 19 December 2022.

- Madgavkar, A. Debt-for-Adaptation Swaps: A Financial Tool to Help Climate Vulnerable Nations. 21 March 2023. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/debt-for-adaptation-swaps-a-financial-tool-to-help-climate-vulnerable-nations/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Bramble, B. A Brief Summary of Debt-for-Nature Swaps. USAID Debt-for-Nature Ad Hoc Working Group; 1988. Available online: https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Xnaba882b.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2023).

- Aligiri, P. Give Us Sovereignty or Give Us Debt: Debtor Countries’ Perspective on Debt-for-Nature Swaps. Am. Univ. Law Rev. 1992, 41, 495–504. Available online: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol41/iss2/4/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- ADB. Debt-for-Nature-Swaps: Feasibility and Policy Significance in Africa’s Natural Resources Sector. October 2022. Available online: https://www.greenpolicyplatform.org/sites/default/files/downloads/resource/debt-for-nature-swaps.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- TFCA. Debt-for-Nature Initiatives and the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (TFCA): Status and Implementation. 24 July 2018. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL31286/16 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- The Nature Conservancy. Ocean Protection with NatureVest. Available online: https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/who-we-are/how-we-work/finance-investing/naturevest/ocean-protection/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- The Commonwealth. Case Study: Innovative Financing—Debt for Conservation Swap, Seychelles’ Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust and the Blue Bonds Plan, Seychelles (on-going). Available online: https://thecommonwealth.org/case-study/case-study-innovative-financing-debt-conservation-swap-seychelles-conservation-and (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- The Nature Conservancy. Blue Bonds: An Audacious Plan to Save the World’s Oceans. 27 July 2023. Available online: https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our-insights/perspectives/an-audacious-plan-to-save-the-worlds-oceans/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- The Nature Conservancy. Six Global Environmental Organizations Unite to Scale Climate and Conservation Outcomes Through Sovereign Debt Conversions. 29 October 2024. Available online: https://www.nature.org/en-us/newsroom/new-debt-coalition-for-climate-and-conservation/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Georgieva, K.; Chamon, M.; Thakoor, V. Swapping Debt for Climate or Nature Pledges Can Help Fund Resilience. 14 December 2022. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/12/14/swapping-debt-for-climate-or-nature-pledges-can-help-fund-resilience (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. The United States and Indonesia Sign $35 Million Debt Swap Agreement to Support Coral Reef Ecosystems. 8 July 2024. Available online: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2451 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- BondbloX. El Salvador Announces Tender Results. 14 October 2024. Available online: https://bondblox.com/news/el-salvador-announces-tender-offer-results (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- BondbloX. Ecuador Launches Buyback as Part of Debt-for-Nature Swap. 4 December 2024. Available online: https://bondblox.com/news/ecuador-launches-buyback-as-part-of-debt-for-nature-swap (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- S&P Global. El Salvador ‘B-/B’ Ratings Affirmed on Debt Repurchase Offer Announcement; Outlook Remains Stable. 10 October 2024. Available online: https://disclosure.spglobal.com/ratings/en/regulatory/article/-/view/type/HTML/id/3265909 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Clifford Chance. Debt-for-Nature Swaps: A New Generation. November 2023. Available online: https://www.cliffordchance.com/content/dam/cliffordchance/briefings/2023/11/debt-for-nature-swaps-a-new-generation.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Moody’s Analytics. Moody’s Analytics Default & Recovery Database (DRD): Frequently Asked Questions and Reference Guide. Available online: https://www.moodys.com/sites/products/ProductAttachments/DRD%20Documentation%20v2/DRDV2_FAQ.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- U.S. International Development Finance Corporation. World’s Largest Debt Conversion for Conservation of a River and Its Watershed Completed in El Salvador. 16 October 2024. Available online: https://www.dfc.gov/media/press-releases/worlds-largest-debt-conversion-conservation-river-and-its-watershed-completed (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- U.S. International Development Finance Corporation. DFC Announces $1 Billion in Political Risk Insurance for Ecuador’s First Debt Conversion to Support Terrestrial and Freshwater Conservation in the Amazon. 17 December 2024. Available online: https://www.dfc.gov/media/press-releases/dfc-announces-1-billion-political-risk-insurance-ecuadors-first-debt (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- The Nature Conservancy. Belize Blue Bonds for Ocean Conservation Impact Report. 30 June 2023. Available online: https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/who-we-are/how-we-work/finance-investing/naturevest/belize-blue-bonds-for-ocean-conservation-annual-impact-report/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- The Nature Conservancy. The Nature Conservancy Announces Innovative Nature Bonds Project in The Bahamas. 21 November 2024. Available online: https://www.nature.org/en-us/newsroom/tnc-announces-new-nature-bonds-project-bahamas/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Grund, S.; Fontana, S. Debt-for-Nature Swaps: The Belize 2021 Deal and the Future of Green Sovereign Finance. Cap. Mark. Law J. 2023, 19, 128–151. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4437615 (accessed on 21 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Nedopil, C. (Re)orienting Sovereign Debt to Support Nature and the SDGs: Instruments and Their Application in Asia-Pacific Developing Economies. July 2023. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/372787960_Reorienting_Sovereign_Debt_to_Support_Nature_and_the_SDGs_Instruments_and_their_Application_in_Asia-Pacific_Developing_Economies (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Duarte, E. Gabon Offers Juicier-Than-Expected Yield in Debt-for-Nature Deal. 7 August 2023. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-08-07/bofa-sweetens-yield-on-gabon-blue-bond-sale-to-lure-investors (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Roy, S.; Walsh, T. Gabon Finally Closes Debt-for-Nature Swap.

- White, N. Debt Swaps Arranged by Credit Suisse, BofA Face Scrutiny. 18 September 2023. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-17/debt-swaps-arranged-by-credit-suisse-bofa-come-under-scrutiny (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- International Capital Markets Association. Bonds to Finance the Sustainable Blue Economy: A Practitioner’s Guide. September 2023. Available online: https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/Bonds-to-Finance-the-Sustainable-Blue-Economy-a-Practitioners-Guide-September-2023.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- White, N. Debt Sold by Credit Suisse, BofA Loses Blue Label with Funds. 3 October 2023. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-03/debt-sold-by-credit-suisse-bofa-loses-blue-label-with-funds (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Bredholt, C. Gabon Blue Bond Master Trust, Series 2: Issuer In-Depth. 25 July 2023. Available online: https://www.moodys.com/research/Gabon-Blue-Bond-Master-Trust-Series-2-New-issuer-debt-Issuer-In-Depth--PBC_1375199. (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- White, N. Gabon Coup Tests Two-Week-Old $500 Million BofA Debt Swap. 31 August 2023. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-08-31/gabon-coup-tests-two-week-old-500-million-bofa-debt-swap (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements. Financing the 30×30 Agenda for the Oceans: Debt for Nature Swaps Should Be Rejected. Available online: https://www.cffacape.org/publications-blog/joint-statement-financing-the-30x-30-agenda-for-the-oceans-debt-for-nature-swaps-should-be-rejected (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- The Nature Conservancy. Case Study: Belize Blue Bonds for Ocean Conservation. 17 May 2022. Available online: https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/TNC-Belize-Debt-Conversion-Case-Study.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- International Monetary Fund. Belize 2022 Article IV Consultation—Press Release; and Staff Report; IMF Country Report No. 22/133; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Belize National Assembly. Resolution for the Expansion of the Protection of Belize’s Total Ocean Space and the Medium Bio-Diversity Protection Zones Motion. Belize Senate No. 36/1/14. Available online: https://www.nationalassembly.gov.bz/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Orders-of-the-Day-Thursday-21st-November-2024.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Novelo, H. Rushed Conservation: Is Belize’s Blue Bonds Deal Sacrificing Fishermen for Global Praise? 31 October 2024. Available online: https://edition.channel5belize.com/rushed-conservation-is-belizes-blue-bonds-deal-sacrificing-fishermen-for-global-praise/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).