1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of digital technologies has significantly transformed the landscape of education, particularly in the realms of language learning and intercultural studies [

1]. Virtual worlds, characterized by their immersive and interactive nature, have emerged as powerful tools for creating engaging and effective learning environments [

2]. These digital spaces offer unique opportunities for multi-user interactions, collaborative group work, and realistic simulations that can enhance both language acquisition and intercultural understanding [

3].

Language learning in virtual worlds has gained considerable attention due to its potential to provide authentic communication contexts and reduce language anxiety. The immersive nature of these environments allows learners to engage in meaningful interactions, negotiate meaning, and practice language skills in a low-stress setting. Moreover, the use of avatars and the sense of presence in virtual worlds can contribute to increased confidence and motivation among language learners [

4].

Simultaneously, virtual worlds have shown promise in fostering intercultural competence and empathy [

5]. By facilitating interactions between individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds, these platforms can promote cultural awareness, challenge stereotypes, and develop critical perspectives on global issues. The ability to simulate various cultural contexts and scenarios within virtual worlds provides learners with unique opportunities to experience and reflect on intercultural encounters in a safe and controlled environment.

Furthermore, virtual reality (VR) and virtual worlds (VWs) have emerged as promising tools to enhance student motivation in education by providing immersive, interactive, and engaging learning experiences [

6,

7]. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) suggests that VR environments can support students’ psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, thereby fostering intrinsic motivation [

8,

9]. Empirical studies have demonstrated the motivational benefits of VR across various educational domains, showing increased presence, engagement, and learning outcomes [

6,

10,

11]. However, potential challenges such as the novelty effect, technical difficulties, and cognitive overload must be addressed through their careful design and implementation [

6,

9]. Further research is needed to explore the long-term effects, individual differences, and best practices for integrating VR and VW into education to harness their motivational potential and create compelling learning environments that promote student success.

Despite the growing body of research on virtual worlds in education, there remains a need for comprehensive studies that examine the combined impact of these environments on both language learning and intercultural understanding. Additionally, while previous studies have highlighted the potential benefits of virtual worlds, challenges related to technology integration, user experience, and pedagogical design persist.

This study aims to address these gaps by investigating the effects of multi-user interaction, group work, and simulations within a virtual world on language learning outcomes and the development of intergroup empathy. By focusing on both linguistic and intercultural aspects, this research seeks to provide a holistic understanding of the educational potential of virtual worlds. Furthermore, the study explores the challenges and opportunities associated with implementing virtual world-based learning experiences, contributing to the ongoing discourse on best practices in digital education.

This study synthesizes findings from two research projects that explore the impact of multi-user interactions, group work, and simulations within a virtual world on language learning and the development of intergroup empathy. The manuscript is structured as follows: the literature review provides a comprehensive overview of existing research on virtual worlds and their applications in education; the methodology section details the design and implementation of our studies; the results section presents the key findings from both studies; and the discussion interprets these findings in the context of current educational practices, highlighting the implications for educators and researchers.

There are five main research questions that guided this study:

How do multi-user interactions and collaborative activities within a virtual world environment impact language learning outcomes and learner engagement?

In what ways do simulations and role-playing experiences in virtual worlds contribute to the development of intergroup empathy and intercultural understanding?

What are the perceived benefits and challenges of using virtual world environments for language learning and intercultural education from the perspective of participants?

How does structured reflection within virtual world experiences enhance language acquisition and empathy development?

What technical and pedagogical considerations emerge when implementing virtual world-based learning for language and intercultural education?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Collaboration in Virtual Worlds

It is important to clarify the distinctions between virtual reality (VR), virtual worlds, and immersive technologies, as these terms are often used interchangeably but have specific meanings. Virtual reality refers to a computer-generated simulation of a three-dimensional environment that can be interacted with in a tangible way using special electronic equipment, such as VR headsets. Virtual worlds, on the other hand, are persistent, shared, online environments where users can interact with each other and digital objects, often through avatars, but do not necessarily require immersive hardware. Immersive technologies encompass a broader range of tools and platforms that create a sense of presence or immersion, including both VR and virtual worlds, as well as augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR) experiences. In this study, we focus specifically on virtual worlds as online, multi-user environments that do not require VR hardware for access. Virtual worlds offer unique opportunities for collaboration in education, as the immersive and interactive nature of these environments facilitates active engagement and participation among learners [

12,

13].

Collaborative activities in virtual worlds, such as pair work, group projects, and simulations, provide opportunities for authentic and situated learning experiences, allowing students to practice skills, engage in problem-solving, and apply their knowledge in meaningful contexts [

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, collaboration in virtual worlds can foster a sense of community and social presence among learners, reducing feelings of isolation and promoting positive learning outcomes [

17]. However, the success of collaborative learning in virtual worlds depends on effective instructional design, facilitation, and technical support to ensure their smooth implementation and address potential challenges [

18,

19].

2.2. Gamification in Virtual Worlds

Gamification, which involves the integration of game design elements into non-game contexts [

20], has proven to be an effective approach to enhance learner motivation and engagement in virtual world educational settings, including language instruction [

21]. By incorporating features such as rewards, leaderboards, challenges, and badges, gamification can foster a sense of accomplishment, competition, and progress that motivates learners to persist in their learning endeavors [

22]. A comprehensive meta-analysis conducted by Lampropoulos and Kinshuk [

23] examined 112 studies that investigated the combination of gamification and virtual worlds. The findings revealed that gamification can have a positive impact on educational activities and enrich virtual reality experiences, resulting in more interactive, engaging, and motivating learning environments. Most of the studies reported favorable outcomes in terms of learning achievements and student satisfaction.

Further research has demonstrated that gamified learning activities in virtual worlds can improve learner motivation, engagement, and performance [

24,

25]. Moreover, gamification in virtual worlds can encourage self-directed learning and autonomy, as learners are empowered to take control of their learning progress and make decisions about which tasks to prioritize and complete. Lampropoulos and Kinshuk [

23] argue that gamified virtual reality is a powerful educational tool that can enhance learning across all educational levels, subjects, and contexts. However, to ensure the effectiveness of gamification in virtual world education, careful design and implementation are essential. This involves aligning game elements with pedagogical principles and learning objectives while addressing potential challenges such as technical limitations and the need for teacher training and support. Educators must strike a balance between providing an engaging and entertaining learning experience and maintaining a focus on the desired learning outcomes. Additionally, it is crucial to consider the specific needs and preferences of the learners when designing gamified virtual world environments to ensure that the experience is tailored to their interests and abilities [

26]. By carefully designing and implementing gamification strategies in virtual world education, educators can create immersive and motivating learning experiences that promote active engagement, knowledge retention, and skill development.

2.3. Empathy

The use of virtual worlds offers unique opportunities for developing empathy, which is required to feel what another person is experiencing. Perspective-taking, often through role-playing, is seen as one of the most effective ways to achieve this [

27]. Empathy can be categorized into three types or stages: empathic resonance, empathic reasoning, and empathic response [

28].

In virtual worlds, the Proteus effect takes place, where the individual identifies with their character [

29]. The Proteus effect refers to the phenomenon where an individual’s behavior in a virtual environment is influenced by the characteristics of their avatar. Virtual reality can serve as the “ultimate empathy machine”, allowing people to experience the perspective of others in an immersive and direct way [

30].

Studies have shown that virtual reality perspective-taking can lead to long-term increases in empathy [

5], induce greater empathy and more positive attitudes toward unhoused people [

31], and enhance empathy by bridging the empathy gap [

32]. Research in Israel demonstrated the potential of experiential learning in virtual worlds to help students examine prejudices and feel empathy towards others [

33]. Another study showed that changes in empathy towards people with disabilities were evident more than a year after doing a simulation in a virtual world [

34].

Virtual reality provides controlled simulations that can offer challenging encounters in a safe environment. Thanks to the Proteus effect, the participant will feel connected and empathetic towards the cultural or character group that their avatar represents [

35]. As Milk concludes, “through this machine, we become more compassionate, more empathetic, more connected. And we become better humans” [

30].

2.4. Virtual Reality and Language Acquisition

Virtual worlds and immersive technologies have been increasingly recognized as powerful tools for language learning, offering learners opportunities to engage in authentic communication, collaborate with peers, and experience target language environments [

36]. Research has shown that immersive virtual metaverse platforms can enhance various aspects of language proficiency [

37,

38,

39], including anxiety with speaking the language [

40,

41].

Several studies have investigated the impact of virtual reality on learners’ speaking skills. Studies have found that EFL learners who participated in VR-based activities showed significant improvements in their oral proficiency compared to those who engaged in traditional classroom activities [

42]. Similarly, Parmaxi’s [

39] systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that virtual worlds can positively impact language acquisition, particularly in terms of speaking skills. The author highlights the potential of virtual worlds to provide immersive and interactive learning experiences that promote authentic language use and collaboration among learners.

Virtual reality has also been shown to enhance learners’ listening comprehension [

42]. Kim et al. [

43] examined the impact of virtual reality on Korean language learners’ listening comprehension and reported positive results, with VR-based instruction leading to better listening performances and increased learner motivation. Hua and Wang’s [

44] review of virtual reality-assisted language learning research from 2018 to 2022 also revealed that virtual reality technologies have been used to improve listening skills.

Research suggests that virtual reality can facilitate vocabulary acquisition. Hua and Wang’s [

45] review highlights the benefits of virtual reality in creating realistic and engaging learning environments that facilitate language practice, including vocabulary acquisition. However, less research has been carried out on the effectiveness of using virtual worlds to enhance grammatical accuracy in language learners [

46]. The immersive and interactive nature of virtual worlds could provide learners with opportunities to practice and reinforce grammatical structures in authentic contexts.

In summary, the growing body of research on virtual reality and language acquisition highlights the potential of immersive technologies to enhance various aspects of language learning, including speaking, listening, and vocabulary. Virtual worlds and virtual reality environments can provide learners with authentic, engaging, and collaborative learning experiences that promote language proficiency and learner motivation. As technology continues to advance, it is likely that virtual reality will play an increasingly key role in language education, offering new opportunities for learners to immerse themselves in target language environments and interact with native speakers.

2.5. Cultural Competence

Immersive technologies, particularly virtual reality, have emerged as powerful tools for promoting cultural competence and intercultural communication skills across various disciplines, including language learning. In language education, virtual reality technologies have been applied to enhance cultural competence by providing learners with authentic cultural contexts and facilitating social interactions in the target language [

37,

45]. The immersive nature of virtual reality allows language learners to experience and engage with diverse cultural settings, leading to increased cultural awareness, understanding, and practical skills for effective intercultural communication.

Virtual reality has also been recognized as a valuable tool for fostering cultural competence in fields such as healthcare [

46] and social work [

47]. By immersing learners in virtual scenarios that replicate real-world cultural challenges, virtual reality simulations expose students to diverse cultural contexts and provide them with opportunities to practice culturally responsive skills in a safe and controlled environment. These immersive experiences help learners gain a deeper understanding of cultural differences, develop strategies for effective cross-cultural communication, and build confidence in their ability to work successfully in diverse cultural contexts.

2.6. Teacher Presence

Language learning in virtual environments benefits significantly from active teacher involvement [

48]. Teachers can provide essential guidance, feedback, and support while designing and implementing effective learning activities that leverage the unique affordances of virtual environments [

49]. Teacher presence is a crucial factor in the success of virtual learning environments. It plays a significant role in facilitating learning, offering support, and fostering a sense of community among learners [

50]. In the context of pair work, group work, and multi-user activities in virtual reality (VR), the teacher’s presence becomes even more important, as it helps guide and structure collaborative learning experiences.

Research has shown that a teacher’s presence in virtual learning environments can positively impact student engagement, motivation, and learning outcomes [

51,

52]. By providing clear instructions, facilitating discussions, and offering timely feedback, teachers help learners navigate the complexities of collaborative activities in VR, ensuring that learning objectives are met.

Moreover, teacher presence in VR can help establish a sense of social presence and co-presence among learners [

13]. By actively participating in collaborative activities and modeling effective communication and collaboration skills, teachers can create a supportive and inclusive learning environment that promotes learner interaction and engagement.

To enhance teacher presence in VR-based collaborative activities, several strategies can be employed:

Providing clear instructions and expectations;

Facilitating discussions and encouraging interactions;

Offering timely feedback and support;

Modeling effective communication and collaboration skills;

Fostering a sense of community and social presence.

By implementing these strategies, teachers can enhance their presence in VR-based collaborative activities, supporting learners in achieving positive learning outcomes and developing essential skills. However, for this to occur, the teachers need to undergo training both in the virtual world and in the pedagogy of teacher presence in virtual worlds

2.7. Reflection and Virtual Worlds

Reflection plays a crucial role in the learning process, allowing learners to make sense of their experiences, consolidate knowledge, and develop new insights [

53,

54]. In virtual world learning environments, reflection takes on added significance as learners navigate complex, immersive experiences that may challenge their assumptions and broaden their perspectives [

55,

56]. Research has shown that intentionally integrating reflective practices within virtual world courses can enhance learning outcomes, promote deeper understanding, and foster the transfer of knowledge to real-world contexts [

57]. By engaging in reflection, learners can critically examine their virtual experiences, identify personal growth opportunities, and develop strategies for applying their newfound knowledge and skills beyond the virtual environment [

57].

2.8. Technical Difficulties and Challenges in Using Virtual Reality

Despite the numerous advantages of virtual reality (VR), it is essential to acknowledge and address the technical difficulties and challenges that may arise when implementing VR-based learning environments. These challenges can significantly impact learners’ experiences and hinder the effectiveness of the learning process.

One of the primary concerns is the accessibility of VR technology. Many learners may not have access to the necessary hardware, such as high-performance computers or VR headsets, which can be expensive and require specific technical specifications. This digital divide can create disparities in learning opportunities, favoring those with access to the required technology.

Moreover, the stability and reliability of VR systems can be a significant challenge. Technical glitches, software bugs, and connectivity issues can disrupt the flow of learning and cause frustration among learners [

58]. These technical problems can be particularly detrimental in language learning contexts, where immersion and interaction are crucial for effective learning.

Another challenge is the learning curve associated with VR technology. Learners may require considerable time and effort to familiarize themselves with the VR’s interface, controls, and navigation [

59]. This learning curve can be steep, especially for those who are less technologically savvy or have limited experience with VR. Consequently, educators must allocate sufficient time for orientation and training to ensure that learners can effectively engage with the VR environment.

The cognitive load imposed by VR-based learning is another consideration. The immersive nature of VR can be overwhelming for some learners, leading to cognitive overload and potential discomfort [

60]. Educators must carefully design VR experiences that balance immersion and cognitive demands, ensuring that learners can focus on language learning tasks without being overwhelmed by technology.

The use of virtual worlds in education, while beneficial, also entails certain risks and potential adverse effects. The prolonged use of virtual environments can lead to physical discomfort, including eye strain, headaches, and motion sickness, necessitating the careful monitoring and management of these symptoms to ensure participant well-being. Additionally, immersive virtual experiences can evoke strong emotional responses, which, while potentially beneficial for empathy development, may also lead to negative emotions such as frustration, anger, or sadness. To mitigate these psychological effects, providing support and debriefing sessions is crucial. Furthermore, the digital divide presents a significant challenge, as access to the necessary technology and internet connectivity can be a barrier for some participants, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities. Therefore, efforts should be made to ensure equitable access to virtual world-based learning opportunities, addressing these challenges to maximize the benefits of virtual worlds in education while minimizing the potential risks.

To mitigate these challenges, it is crucial to provide comprehensive technical support and guidance to both educators and learners. This support should include clear instructions, troubleshooting resources, and real-time assistance [

61]. Institutions should invest in robust infrastructure, reliable VR systems, and dedicated technical support teams to ensure the smooth functioning of VR-based learning environments.

Furthermore, educators should adopt a learner-centered approach when designing VR-based language learning activities. They should consider learners’ diverse needs, technological backgrounds, and proficiency levels, providing differentiated support and accommodations as necessary [

62]. By creating inclusive and accessible VR learning experiences, educators can help learners overcome technical barriers and fully engage in immersive language learning.

In all areas of using virtual worlds, it is important to note that learning in the metaverse does not mean that you will learn the language or acquire cultural competencies, as the pedagogy determines the power of the tool [

63]. In addition, we need to be mindful of potential physical and psychological issues involved in learning with VR [

64].

In conclusion, while VR offers immense potential for language learning, it is essential to acknowledge and address the technical difficulties and challenges associated with its implementation. By providing comprehensive technical support, investing in robust infrastructure, and adopting learner-centered approaches, educators can create effective and inclusive VR-based language learning environments that maximize the benefits of this innovative technology.

The literature review presented in this study provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of research on virtual worlds and their applications in language learning, intercultural understanding, and empathy development. The reviewed studies highlight the potential of virtual worlds to enhance motivation, collaboration, gamification, and reflective practices, all of which contribute to positive learning outcomes. However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the existing research. Many of these studies have small sample sizes and are context-specific, which may limit the generalizability of their findings. Additionally, the rapid pace of technological advancements means that some of the earlier studies may not fully reflect the current capabilities and challenges of virtual world platforms. Furthermore, while this literature review covers a broad range of topics related to virtual worlds in education, it is not exhaustive, and there may be additional factors or considerations that have not been fully addressed. Despite these limitations, this literature review provides a solid foundation for understanding the potential of virtual worlds in language learning and intercultural education, and it highlights the need for continued research to explore the long-term effects, best practices, and strategies for overcoming technical and pedagogical challenges. Moreover, the effectiveness of learning in virtual worlds is dependent on the pedagogical approaches employed by educators, emphasizing the importance of intentional instructional design and facilitation in optimizing learning outcomes [

63]. As virtual worlds continue to evolve, it is crucial for researchers and educators to stay informed about the latest developments and to collaborate in designing engaging, effective, and inclusive virtual learning experiences while being mindful of the potential physical and psychological issues associated with learning in immersive environments [

64].

3. Methodology

This study employed a qualitative approach to investigate the impact of multi-user interactions, group work, and simulations within a virtual world on language learning and the development of intergroup empathy.

In the process of analyzing the data and preparing this manuscript, we utilized AI-powered language tools, including Perplexity AI, to assist with tasks such as summarizing research findings, identifying key themes, and refining the article’s structure. These tools were employed to enhance the efficiency of the writing process and to ensure clarity in presenting complex ideas. However, all interpretations, conclusions, and the final content of the article were thoroughly reviewed and validated by the human authors to maintain the integrity of the research.

3.1. Participants

There were 241 students involved in the two studies, with a total of 116 in the English immersion study and 125 in the intercultural education study. Participants were recruited from six culturally diverse educational colleges in Israel. Students were studying for a B.Ed. degree or M.Ed. degree and had taken basic technological courses prior to this course. The study included a broad age range, from 19 to 45. The majority of the students were female (86%), as less men are enrolled in state teaching colleges in Israel. The inclusion criteria required participants in the English speaking study to have a minimum B1 level (intermediate) of language proficiency as defined by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR).

The participants in this study were drawn from six culturally diverse educational colleges in Israel, encompassing a broad spectrum of backgrounds. This diverse range includes religious and secular individuals, Muslims and Jews, and students from both urban centers and outlying areas. These categories were chosen to reflect the complex and multifaceted nature of Israeli society, where cultural, religious, and geographical distinctions significantly influence individuals’ experiences and perspectives. By including participants from such varied backgrounds, we aimed to capture a wide range of viewpoints and interactions, thereby enriching the study’s findings on language learning and intercultural empathy within virtual worlds.

3.2. Virtual World Platform

The virtual world environment was created using the OpenSim Version (4.3) platform. OpenSim is an open-source virtual world platform that allows for the creation of customizable and immersive 3D environments. The choice of OpenSim was based on its flexibility, cost-effectiveness, and ability to support multi-user interactions and complex simulations.

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected through three primary methods:

- *

Open-ended questionnaires distributed at the end of each course.

- *

Semi-structured interviews conducted with approximately 10% of participants.

- *

Observational data gathered during virtual world sessions.

The open-ended questionnaires and semi-structured interviews were designed to explore participants’ overall experience in the virtual world, their engagement with various learning strategies, perceived learning outcomes, and reflections on intergroup empathy and understanding.

For example, the questions asked by the interviewer for the language course included:

Do you think your English improved throughout the course?

Do you feel that you were immersed into the language?

What motivated you to work while doing the course?

What was the biggest challenge in the course?

Do you feel more confident speaking in English now?

And the questions for the intercultural course included:

Did the Disabled/Arab/Obese experience change your perspective?

Do you think simulations are an effective way to learn about “the other” in schools and education in general? (Different cultures, gender preferences, religions, disabilities, etc.) Explain.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations were paramount in the design and implementation of this study. All participants provided informed consent prior to their involvement, ensuring that they were fully aware of the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. The study received ethical approval from the relevant institutional review boards, confirming that all procedures adhered to ethical standards for research involving human participants. Participants’ data were anonymized to protect privacy, and confidentiality was maintained throughout the data collection, analysis, and reporting processes.

Given the diverse cultural and religious backgrounds of our participants, we took special care to respect their cultural and religious sensitivities, providing options for participation that accommodated their beliefs and practices. After their virtual world experiences, participants were debriefed to discuss their reactions and provide support if needed. This was particularly important for those who experienced strong emotional responses during the simulations. These measures collectively ensured the ethical nature of the research while promoting open and honest participation.

3.5. Data Analysis

The data analysis process followed a rigorous, systematic approach using Atlas.ti V ersion (22.0.1), a qualitative data analysis software. A thematic analysis was conducted by importing all qualitative data from questionnaires, interview transcripts, and observational notes into Atlas.ti. The initial coding identified recurring patterns and themes, which were then refined and organized into broader categories. Network views in Atlas.ti visualized the relationships between themes. The content analysis utilized Atlas.ti’s word frequency and co-occurrence tools to identify key concepts and their relationships, while quotation retrieval features extracted relevant participant statements for each theme. To ensure inter-coder reliability, two independent researchers, both with extensive experience in qualitative research and backgrounds in language education and intercultural studies, coded a subset of 20% of the data. This sample size is consistent with recommendations in the qualitative research literature for establishing coding reliability [

65]. The researchers independently coded the data using the codebook developed from the initial analysis. We then calculated Cohen’s kappa coefficient using Atlas.ti’s inter-coder agreement tool to measure the reliability between coders. The resulting kappa coefficient was 0.85, indicating strong agreement between the coders. This level of agreement is considered excellent in qualitative research [

66].

The two researchers were selected based on their complementary expertise: one specializing in language acquisition and the other in intercultural communication. Both researchers have over five years of experience in qualitative data analysis and are fluent in the languages used by participants. Their diverse backgrounds allowed for a comprehensive interpretation of the data, capturing nuances in both the language learning and cultural aspects of the study.

After the initial coding, the researchers met to discuss and resolve any discrepancies, further refining the coding scheme. Methodological support included the triangulation of data from multiple sources, member checking with a subset of participants, peer debriefing among researchers using Atlas.ti’s collaborative features, maintaining an audit trail for transparency and replicability, and providing thick descriptions of participants’ experiences, facilitated by Atlas.ti’s quotation management features. These measures collectively ensured the validity and reliability of the results.

3.6. Methods

This study employs a qualitative approach to investigate the impact of multi-user interactions, group work, and simulations within a virtual world on language learning and the development of intergroup empathy. This research’s design is based on two distinct yet related studies, each focusing on different aspects of the virtual world experience.

In the first study, focusing on language learning, participants engaged in various networking strategies within a virtual world. The study aimed to explore the effectiveness of these strategies in enhancing language acquisition, as well as participants’ enjoyment and time spent in the virtual world. Participants were recruited from a language learning course that utilized a virtual world platform, with a total of 116 undergraduate students agreeing to take part in the study from six culturally diverse educational colleges in Israel. The students studied ten units in the virtual world. The virtual metaverse platform used in this study is part of an advanced speaking course at the B2 level (advanced intermediate). The activities took place in “Englehaven”, a town built for the course on the OpenSim platform. Each unit took the students to a different area (airport, bank, estate agents, university, etc.) and focused on a different speech act and set of vocabulary. The assignments became progressively more demanding as far as spoken English was concerned and culminated in giving two-minute speeches.

Each unit contained 6 activities; some were individual (working on a song, practice exercises, doing a quiz, watching comedy clips), other activities required them to interact with a bot (role-playing, simulations), and others involved pair work or group work (games, collaborative exercises, quests). For example,

Figure 1 shows the debating area where 2 students choose a topic to debate; they write points for and against the motion and, when they are ready, they are placed arbitrarily for or against the notion. Phrases and expressions appear on their screen to help them debate the topic. They press the start button and each speaker has 30 s to present a point. After practicing a number of debates, the students meet the teacher and debate together. They receive feedback and a grade from the teacher. The majority of activities incorporated gamified tasks to facilitate language learning, as well as extra activities to ensure there was always something to do. Teachers were present in the virtual metaverse at allocated times to provide guidance, feedback, and support to learners throughout the course, and each unit culminated in an assignment with the teacher (including an interview, interrogation, elevator pitch, or giving a two-minute speech). A few teachers were involved in the development of the course, while others were trained to be online teachers for the course. Short videos and written material were developed to explain what the teacher needed to do in each unit.

The second study, examining intergroup empathy, involved participants collaborating in small multicultural groups and participating in simulations where they experienced being in someone else’s shoes, such as being obese, confined to a wheelchair, an Orthodox Jew, or a Syrian refugee. This study sought to investigate the potential of experiential learning and simulations in promoting social proximity, tolerance, and cooperation in diverse societies. A total of 125 participants were recruited from a course on intercultural understanding that incorporated a virtual world component. The semester-long course comprised eight units. In addition to the course material, there were simulations in each unit in the virtual world. The students worked in small multicultural teams of six students, meeting in the virtual world each week. They were required to reflect on their learning and experiences in their groups or individually. In

Figure 2 below you can see a number of students doing an activity together where they are each on a lane in a sports stadium and can only advance if they answer the questions positively (for example, are you male? Did your parents pay for private lessons for you?). After the activity, the students reflected on where they were in relation to their peers and the advantages they had or did not have when growing up.

In the intercultural study, we leveraged principles of embodied cognition to enhance the authenticity of role-play and foster intergroup empathy. Participants were not merely assigned roles; they were immersed in these roles through carefully designed avatar characteristics and environmental constraints.

In designing the virtual world experiences to foster intergroup empathy, we carefully crafted avatars and environments to immerse participants in their assigned roles. Avatars were customized to visually reflect specific characteristics, such as larger body sizes for the simulation of “obesity” or wheelchairs for mobility-impaired roles. We programmed movement restrictions for certain avatars, like confining wheelchair users to their virtual chairs, limiting their mobility and access within the environment.

Clothing and accessories were tailored to each role, including culturally or religiously appropriate attire for simulations involving diverse ethnic or religious groups. The virtual world itself was constructed with intentional physical barriers and social situations to highlight the challenges faced by different groups. For example, we included scenarios with a lack of wheelchair ramps or exclusive club entrances to simulate discrimination.

To enhance immersion and empathy, participants experienced the virtual world from a first-person perspective, seeing through the eyes of their avatar. We also incorporated non-player characters (NPCs) to create more realistic and challenging social interactions. In the wheelchair simulation, some NPCs were programmed to ignore or interact condescendingly with participants, while in the obesity simulation, NPCs might ridicule or criticize the avatar’s physical appearance.

These design elements were crucial in reinforcing role identification and creating authentic experiences that went beyond simple role assignment. By engaging multiple senses and creating physical and social challenges within the virtual environment, participants were able to experience a deeper level of embodiment in their assigned roles, leading to more authentic interactions and, consequently, a greater potential for developing intergroup empathy.

Both courses were semester-long courses containing students from six diverse colleges. In the language course, participants spent between 10 and 40 h in the virtual world during the 14-week semester, while, in the intercultural course, this was between 5 and 15 h.

4. Results

After reviewing and analyzing the data, a number of themes emerged specifically for the language learning study and different themes and sub-categories emerged for the intercultural study. There were also themes and sub-categories that were relevant to both studies. The separate themes will be presented first, followed by the joint themes.

4.1. Themes Specifically from the Language Learning Study

The themes that were specific to the language learning course related to the actual learning of the language, but also to the environment, which induced speaking, lessened the fear of speaking in a foreign language, and had the added value of teacher presence.

4.1.1. Interaction with Teachers and Support

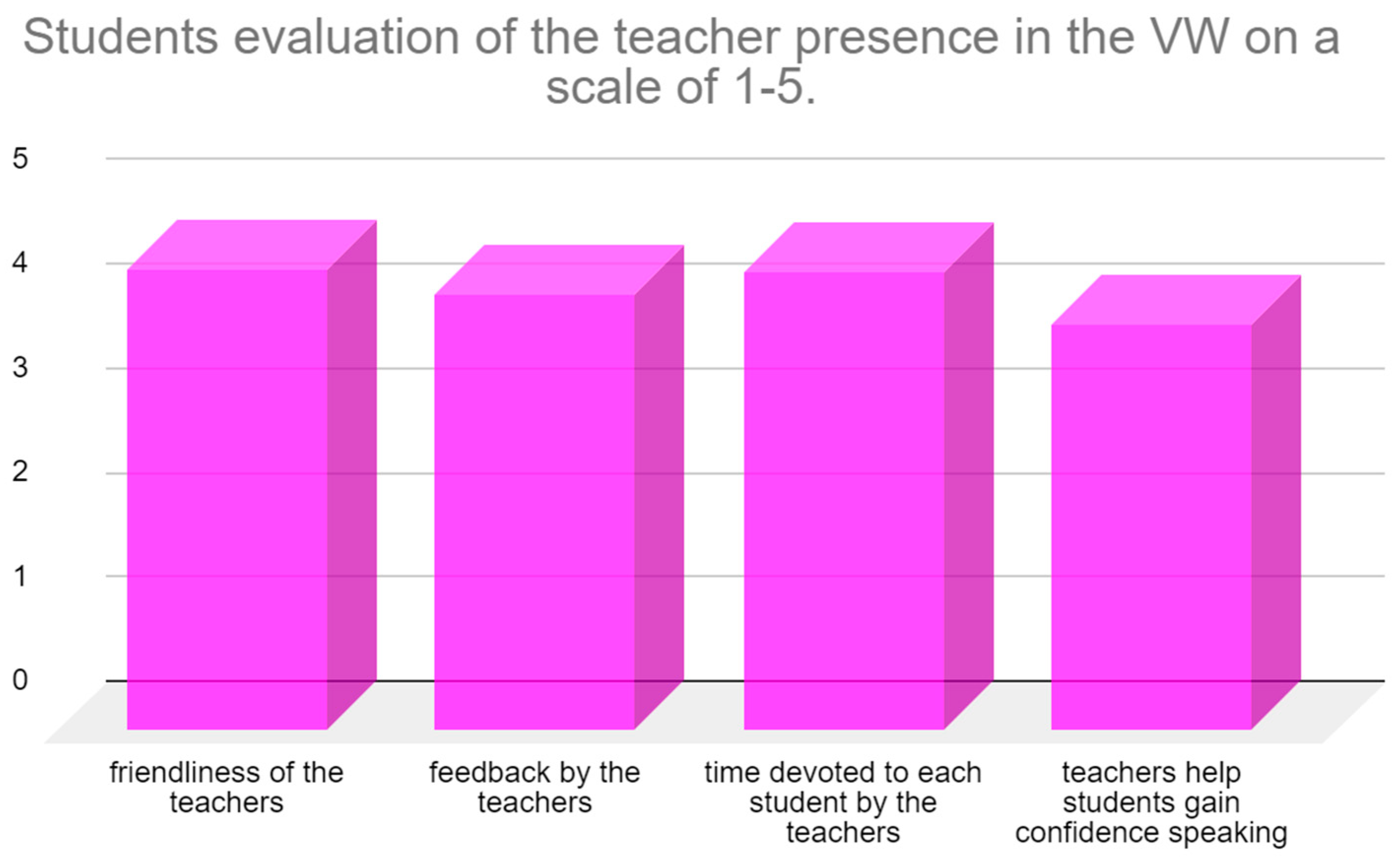

The first theme that emerged was the importance of teacher presence. The presence and assistance of teachers were highly valued by participants in the language learning study (23 mentions). This corroborated the questionnaire, during which the students evaluated the teacher presence in the course on a scale of 1–5, as shown in

Figure 3.

They were asked about the friendliness of the teachers (4.42), feedback from the teachers (4.19), time given to each student by the teachers (4.4), and their ability to help them gain confidence (3.9). Participants emphasized the importance of teacher support in the learning process.

4.1.2. Confidence and Improvement in English

The second theme that emerged related to students feeling confident in speaking in English and the feeling that they had improved in many areas of their English proficiency. The sub-categories are shown in the following pie chart according to their prevalence.

As can be seen in the pie chart in

Figure 4 the sub-themes that emerged were improved speaking (17 mentions), listening, vocabulary, and overall proficiency (39 mentions). The use of avatars in the virtual world helped reduce anxiety and promote confidence (16 mentions), as illustrated by one participant’s comment: “And then when I speak with other students online and the teachers, you cannot be silent, for example you have a minute to describe something, so you have to speak”. Another student said “Normally I don’t speak or participate because I don’t feel confident, but here because it was as if my avatar was speaking I spoke freely and overcame my fear”. Games and gamification elements enhanced motivation (11 mentions), as one student wrote: “It was so much fun I kept coming back, I wanted to get more points to become a millionaire and have my name in the newspaper”, while on-screen prompts and phrases were mentioned by students as a way to trigger language improvement that is not available in the real world. As one student wrote, “When I had to debate, my language was much richer as I had prompts on the screen to choose from”. A student reflected on the impact of the course: “This course has not only reinforced my dedication to learning English but has also sparked excitement for taking more courses in virtual worlds”.

4.2. Themes from the Intercultural Study

Different themes emerged from the intercultural study relating to the area of cultural competencies and changes in attitude towards other groups. Three main themes emerged: an Impact on Perspective and Emotional Responses, an awareness of discrimination, and the final specific theme for this study, which we entitled Relevance, Social Connection, and Intergroup Empathy.

4.2.1. Impact on Perspective and Emotional Responses

The intercultural study revealed a significant impact on participants’ perspectives and emotional responses, as can be seen in

Figure 5 below.

There were 79 mentions of positive changes in perspective and 27 mentions of no change in perspective. As one student wrote, “The course changed my perception of the concept of multiculturalism. As I thought I knew our diverse cultures in Israel, I understood that I was wrong. I realized mainly that the fact that we come from the same country does not necessarily mean that we perceive life in the same way. We learn to live with each other and each one of us brings his diverse cultures to one country”. Participants reported strong emotional responses to the simulations they experienced in the virtual world, including empathy and understanding (60 mentions) and negative feelings such as frustration, anger, and sadness (32 mentions). As one participant shared, “I was so moved by the simulation, it made me so angry to experience being obese and how the people around related to me”.

4.2.2. Awareness of Discrimination

The intercultural study raised participants’ awareness of discrimination issues (39 mentions). As one participant said, “The experience of trying to get into a club and being rejected made me really look at the horrible side of discrimination, the feeling of frustration enveloping the whole experience”. Participants demonstrated increased understanding and empathy towards different ethnic or religious groups (30 mentions).

4.2.3. Relevance, Social Connection, and Intergroup Empathy

Participants related their experiences to previous real-life experiences and projected them onto other contexts or groups, and some called for action to improve society. For example, a number of students stressed the importance of accessibility in public places from their experience of being disabled in a virtual world. The students in this study worked in small intercultural groups (Arabs and Jews), and their perception of commonality between groups was also noted. The intercultural study showed increased social proximity and understanding, as well as positive change in perspective towards diverse groups (79 mentions), increased empathy and understanding (60 mentions), and an appreciation of diversity.

4.3. Joint Themes from Both Studies

We found five main themes that were prevalent in both studies, which we titled as follows: Educational Benefits; Positive Learning Outcomes, Motivation, and Satisfaction; Importance of Reflection; Time Management; and Engagement and Challenges.

4.3.1. Educational Benefits

The first theme included the main advantages the students identified in both studies of studying in a virtual world. The first sub-category was the recognition, from both studies, of the immersive and engaging nature of virtual worlds. The second category relates to the collaborative learning experiences had in the two studies. This included the benefits of group work, pair work, social interactions, and peer support, which were valued by both groups of participants. The fact that the student population was diverse and allowed for multicultural collaboration was also appreciated, contributing to the development of cultural competence. One student reflection noted, “The interactive design of the course was a significant aspect of my improvement. It fostered a sense of community and collaborative learning that was deeply inspiring”.

4.3.2. Positive Learning Outcomes, Motivation, and Satisfaction

Participants reported enjoyment and satisfaction with the course and a high likelihood of recommending both of the courses to others (3.6 average score). Games in the virtual world also contributed to positive learning outcomes, as one student said “It was an amazing experience and I recommend it to everyone. It was so much fun and I learnt a lot as well!”

4.3.3. Importance of Reflection

Reflection on the learning process was an inherent part of the learning experience. This was our third joint theme. Students reflected on the process, and their personal growth and consolidation of their learning were identified as important aspects of the learning process. An example from the intercultural course is a reflection from a student teacher: “I can truly say that this course opened my eyes to things I never knew before, bullying for example, now I know how to deal with bullying in my classroom as a teacher”.

4.3.4. Time Management

Participants in both studies reported frequent logging in and spending a substantial amount of time on the virtual island. However, some participants struggled with balancing course requirements with other commitments. Comments such as “It was very difficult to set time to collaborate”. and “The times set to meet the teacher weren’t convenient for me” were prevalent. A number of students felt that they needed more time to complete the course and that the virtual world took up more time than a normal online course would.

4.3.5. Technology Issues

There were three sub-categories within the theme of technology issues: glitches, technology support, and clear instructions. The glitches included internet connections and problems with the platform, as one student explained: “There are technical problems in the virtual world that need to be solved”. The need for more technical support and the time it took the students to be confident in the learning platform, particularly in the first 4 weeks of the course, formed another category, as one student put it, “It was challenging at first, but then it went smoothly”. It seemed to depend on the technological background of the students, as one student wrote, “Because I have a background in technology it was a very enjoyable experience”. Finally, the need for clear instructions was identified as a challenge and area for improvement. As one student wrote, “Technology was beautiful sometimes! We laughed while listening to the birds. It was my first experience having a course through a virtual world. It wasn’t easy, many times we had difficulties doing the assignments because we didn’t know, for example, how to manage the microphone or to record ourselves”.

4.4. Synthesis of the Two Studies

The qualitative data from both the language learning and intercultural studies highlight the effectiveness of virtual worlds in promoting learning, cultural competence, and empathy. Participants in the language learning study valued the presence and support of teachers, reported increased confidence and improvement in their English skills, and appreciated the immersive and collaborative nature of the virtual world. The intercultural study revealed significant impacts on participants’ perspectives, emotional responses, awareness of discrimination, and increased social connection and intergroup empathy.

Both studies emphasized the educational benefits of virtual worlds, including immersion, engagement, collaborative learning experiences (group work, pair work, social interactions, and peer support), and multicultural collaboration. Participants reported positive learning outcomes, motivation, and satisfaction with the courses, with a high likelihood of recommending them to others (3.6 average score). Reflection was identified as an important aspect of the learning process, contributing to personal growth and understanding.

Time management and engagement were notable themes, with participants spending a substantial amount of time on course activities but sometimes struggling to balance course requirements with other commitments. Technological issues, including glitches (internet connections and platform problems), the need for support and clear instructions, and the time taken for students to become confident with the learning platform, particularly in the first 4 weeks, were identified as challenges and areas for improvement. The impact of these issues varied depending on the students’ technological background.

Overall, the qualitative data from these studies demonstrate the potential of virtual worlds to enhance language learning, cultural competence, and intergroup empathy. The immersive and collaborative nature of virtual worlds, combined with effective course design and support, can lead to positive learning outcomes and transformative experiences for participants, as evidenced by the numerous mentions of increased confidence, improved skills, changed perspectives, and heightened empathy and understanding. However, addressing technological challenges and providing adequate support and clear instructions are crucial for ensuring a smooth and effective learning experience for all participants.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of multi-user interactions, group work, and simulations within virtual worlds in enhancing language learning and fostering intergroup empathy. The results align with previous research on the potential for virtual worlds and networked environments to improve language acquisition [

66,

67,

68,

69] and promote intercultural understanding [

70,

71].

The language learning study revealed that the combination of various networking strategies, such as individual assignments, interactions with bots, pair work, group work, simulations, and working with a teacher, contributed to significant improvements in participants’ speaking, listening, vocabulary, and overall language proficiency. These findings support the notion that immersive and collaborative learning experiences in virtual worlds can facilitate authentic communication and a negotiation of meaning, which are essential for language acquisition [

14,

39,

42,

71].

The use of avatars in the virtual world emerged as a key factor in reducing language anxiety and promoting confidence among participants. This aligns with research demonstrating the motivational benefits of virtual reality in education [

6,

7,

41,

42]. The incorporation of games and gamification elements further enhanced motivation and engagement, corroborating previous findings on the effectiveness of gamification in language learning [

41].

The presence of teachers in the virtual world was highly valued by participants, emphasizing the importance of human guidance and support in technology-enhanced learning environments [

48,

49]. This finding underscores the crucial role of teacher presence in facilitating learning, offering feedback, and fostering a sense of community among learners [

50,

51,

52].

The intercultural study revealed significant impacts on participants’ perspectives, emotional responses, awareness of discrimination, and intergroup empathy. The immersive and experiential nature of the simulations allowed participants to experience being in someone else’s shoes, leading to increased understanding and empathy towards diverse social groups. These findings align with research on the potential of virtual reality to enhance empathy and perspective-taking [

5,

29,

30].

The collaborative work in multicultural groups within the virtual world fostered social proximity, tolerance, and cooperation among participants. This supports the idea that virtual worlds can provide safe and controlled environments for intercultural encounters, promoting positive attitudes and reducing prejudice [

6,

16].

Both studies highlighted the educational benefits of virtual worlds, including immersion, engagement, and collaborative learning experiences. These findings are consistent with research demonstrating the potential of virtual worlds to create compelling and effective learning environments [

12,

71,

72]. The positive learning outcomes, motivation, and satisfaction reported by participants further emphasize the value of virtual worlds in education [

15,

18].

Reflection plays a crucial role in the learning process, allowing learners to make sense of their experiences, consolidate knowledge, and develop new insights [

53,

54]. In virtual world learning environments, reflection takes on added significance as learners navigate complex, immersive experiences that may challenge their assumptions and broaden their perspectives [

55,

56,

57]. However, little research has been carried out to show that intentionally integrating reflective practices within virtual world courses can enhance learning outcomes, promote deeper understanding, and the foster transfer of knowledge to real-world contexts. This study shows that, by engaging in reflection, learners can critically examine their virtual experiences, identify personal growth opportunities, and develop strategies for applying their newfound knowledge and skills beyond the virtual environment.

However, the studies also revealed challenges related to time management and technology issues. Participants sometimes struggled to balance the course requirements with other commitments, and technical difficulties, such as glitches and the need for clear instructions, were identified as potential barriers to learning. These findings echo concerns raised in previous research about the accessibility and usability of virtual reality in education [

6,

59].

To address these challenges, it is crucial to provide comprehensive technical support, invest in robust infrastructure, and adopt learner-centered approaches when designing virtual world learning experiences [

61,

62]. By creating inclusive and accessible virtual learning environments, educators can help learners overcome technical barriers and fully engage in immersive language learning and intercultural experiences.

While the findings of this study largely align with previous research on the potential of virtual worlds in language education and intercultural understanding, there are several notable contributions that extend the existing knowledge in this field. First, this study provides a comprehensive examination of the combined impact of multi-user interactions, group work, and simulations within a single virtual world environment on both language learning outcomes and intergroup empathy. This holistic approach offers new insights into the synergistic effects of these elements on learners’ experiences and outcomes.

Second, this study’s focus on the specific networking strategies employed in the language learning course, such as interactions with bots and on-screen prompts, together with the collaborative learning in the intercultural study, sheds light on innovative approaches to facilitating learning in virtual worlds. These findings suggest that the strategic incorporation of such elements can enhance learners’ confidence, motivation, and language proficiency, as well as promote changes in perception in the intercultural study, offering valuable guidance for educators and instructional designers.

Furthermore, this study’s emphasis on the role of reflection in virtual world learning experiences contributes to a deeper understanding of the importance of reflective practices in promoting personal growth and the consolidation of learning. This finding highlights the need for educators to intentionally integrate opportunities for reflection into virtual world courses to maximize learning outcomes and foster meaningful connections between virtual experiences and real-world applications.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the effectiveness of virtual world learning experiences depends on the pedagogy and instructional design employed by the educators creating and facilitating these courses. The positive outcomes observed in this study can be attributed, in part, to the careful design and implementation of these language learning and intercultural courses, as well as the technical support system. Educators must be intentional in their approach, aligning learning activities, networking strategies, and reflective practices with the desired learning objectives and outcomes.

6. Limitations

While this research offers valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. The study was conducted with participants from six culturally diverse educational colleges in Israel, providing a rich context for the research. However, this specificity may limit the generalizability of the findings to other cultural or educational settings. Additionally, the research focused on the short-term outcomes of virtual world-based learning, while a longitudinal study is necessary to assess the long-term impacts on language proficiency and intercultural empathy. The technical challenges identified during the study were not comprehensively explored, limiting our understanding of how these factors might influence the effectiveness of virtual world-based education. Furthermore, the study relied primarily on qualitative data collection methods; the inclusion of quantitative measures could have provided additional statistical support for the findings and allowed for more robust comparisons.

Another limitation is the lack of an extensive exploration of individual participant characteristics, such as prior technology experience or learning styles, which might have influenced their experiences and outcomes in the virtual world environment. The absence of a control group also limits our ability to definitively attribute the observed outcomes to the virtual world intervention as opposed to other factors. Additionally, this study focused on the OpenSim platform, and its findings may not be fully applicable to other virtual world platforms with different features or capabilities. These limitations provide opportunities for future research to further expand our understanding of virtual world-based education. Despite these constraints, this study offers valuable insights that contribute significantly to the field and provide a foundation for future investigations.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the potential of virtual worlds to enhance language learning and foster intercultural empathy. Our findings reveal that immersive, multi-user virtual environments create engaging educational spaces that transcend traditional classroom boundaries. This research contributes to the field by highlighting the synergistic benefits of combining language learning with intercultural experiences and underscoring the importance of structured reflection in virtual world learning.

This study has significant implications for both researchers and practitioners. For researchers, it suggests the need for longitudinal studies to assess long-term impacts and for further exploration of individual differences among learners. Incorporating quantitative measures alongside qualitative data could provide more robust support for future findings. For practitioners, this study emphasizes the value of integrating virtual world experiences into educational curricula and the importance of addressing technical challenges.

Future research should aim to replicate this study in diverse settings, compare the effectiveness of different virtual world platforms, and include control groups to strengthen causal inferences. Additionally, developing best practices for overcoming technical issues and time management concerns is crucial for optimizing the educational potential of virtual worlds.

As technology advances and educational practices evolve, virtual worlds have the potential to become powerful tools for creating immersive, engaging, and transformative learning experiences. This study lays the groundwork for continued research and development in this promising field of education.