Abstract

Perinatal depression (PND) is a severe mood disorder affecting mothers during pregnancy and postpartum, with implications for both maternal and neonatal health. Emerging evidence suggests that gut microbiota-derived metabolites play a critical role in neuroinflammation and neurotransmission. In this study, we employed an in silico approach to evaluate the pharmacokinetic and therapeutic potential of metabolites produced by Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum in targeting key proteins implicated in PND, including BDNF, CCL2, TNF, IL17A, IL1B, CXCL8, IL6, IL10. The ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiles of selected microbial metabolites, including acetate, lactate, formate, folic acid, riboflavin, kynurenic acid, γ-aminobutyric acid, and vitamin B12 were assessed using computational tools to predict their bioavailability and safety. Enrichment analysis was performed to identify biological pathways and molecular mechanisms modulated by these metabolites, with a focus on neuroinflammation, stress response, and neurogenesis. Additionally, molecular docking studies were conducted to evaluate the binding affinities of these metabolites toward the selected PND-associated targets, providing insights into their potential as neuroactive agents. Our findings suggest that specific microbial metabolites exhibit favorable ADMET properties and strong binding interactions with key proteins implicated in PND pathophysiology. These results highlight the therapeutic potential of gut microbiota-derived metabolites in modulating neuroinflammatory and neuroendocrine pathways, paving the way for novel microbiome-based interventions for perinatal depression. Further experimental validation is warranted to confirm these computational predictions and explore the clinical relevance of these findings.

1. Introduction

Perinatal depression (PND) is a debilitating mood disorder that affects a significant proportion of women during pregnancy and the postpartum period, posing a serious threat to both maternal and infant health [1]. Characterized by persistent sadness, anxiety, and fatigue, PND can impair mother-infant bonding, disrupt cognitive and emotional development in the child, and, in severe cases, lead to devastating outcomes [1]. The etiology of PND is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of hormonal fluctuations, genetic predisposition, psychological stress, and socio-environmental factors [2,3]. Despite its prevalence and impact, current treatment options, primarily consisting of psychotherapy and antidepressant medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), are often limited by variable efficacy, delayed onset of action, and concerns about potential side effects during pregnancy and lactation [2,3,4]. This therapeutic gap underscores the urgent need for novel, safe, and effective intervention strategies.

In recent years, the gut–brain axis has emerged as a pivotal pathway in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression [5]. This bidirectional communication system links the central nervous system (CNS) with the gastrointestinal tract, largely mediated by the gut microbiota and its diverse metabolic output [5]. The gut microbiota produces a vast array of bioactive metabolites that can influence host physiology, including brain function and behavior. Among these, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate, produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fiber, have garnered significant attention for their immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and neuroactive properties [6,7]. Beyond SCFAs, other microbial metabolites, including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), kynurenic acid, and various B vitamins, are also implicated in regulating neurotransmission, neuroinflammation, and stress response pathways [8].

Specific probiotic strains, notably Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum, have been associated with improved mental health outcomes in preclinical and clinical studies (Table 1). These bacteria are prolific producers of neuroactive metabolites. L. helveticus is known for its production of GABA and lactate, while B. longum generates folate, riboflavin, and kynurenic acid, among others [9]. These metabolites are hypothesized to mediate the psychobiotic effects of these strains by modulating inflammatory cytokines, strengthening the gut barrier, influencing the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, and directly interacting with central neurotransmitter systems. However, the precise molecular mechanisms by which these microbial-derived compounds exert their potential antidepressant effects, particularly in the context of PND, remain incompletely understood.

Table 1.

Key microbial metabolites produced by Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum, detailing their typical concentrations, biosynthetic pathways, and documented immunoregulatory and biological effects relevant to gut–brain axis communication.

To bridge this knowledge gap, computational approaches offer a powerful and efficient strategy for the initial screening and characterization of bioactive compounds. In silico methods, including pharmacokinetic prediction and molecular docking, allow for the high-throughput assessment of a compound’s drug-likeness, bioavailability, and binding affinity for specific protein targets. This is especially valuable for prioritizing candidates for further costly and time-consuming experimental validation.

Despite the growing association between specific probiotic strains and mental health benefits, a critical knowledge gap exists regarding the direct interaction of their specific microbial metabolites with key molecular targets involved in PND pathophysiology. The pharmacokinetic profiles, including their ability to be absorbed and cross the blood–brain barrier, and their precise mechanisms of action at a molecular level, remain largely theoretical and poorly characterized.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Bacterial Metabolites

To ensure the reliability and thoroughness of the metabolite data collection, we conducted a systematic review of multiple reference databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Springer, Elsevier ScienceDirect, and Web of Science. Our investigation focused on studies published between 2000 and 2025. To maintain consistency, only English-language articles were included. Keyword searches such as “Lactobacillus helveticus”, “Bifidobacterium longum” and “microbial metabolites” were used to identify relevant studies, focusing on review articles and high-impact primary research. Duplicate entries and irrelevant data were removed during the initial screening process. Strict inclusion criteria were applied, allowing only original research articles, reviews, or book chapters that met predefined standards to be included. This approach ensured the high quality and accuracy of the information gathered.

2.2. Molecular Properties

After identifying the metabolites produced by Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum, their molecular properties were assessed using the SwissADME online platform (http://swissadme.ch, accessed on 20 April 2025). Key parameters, including topological polar surface area (TPSA), atom count, molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, rotatable bonds, partition coefficient (Log P), and adherence to Lipinski’s rule of five, were evaluated. This computational analysis provided valuable insights into the physicochemical and drug-like characteristics of the compounds.

2.3. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity (ADMET) Analysis

Assessing a compound’s pharmacokinetic profile, which includes absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADMET), is critical for understanding its behavior and efficacy within a biological system. Computational tools are invaluable for predicting ADME properties, such as cell membrane permeability, interactions with transporters and enzymes responsible for drug uptake and elimination, and metabolic stability. To analyze the physicochemical properties, drug-likeness, and pharmacokinetic features of the compounds, ADME prediction platforms like SwissADME (http://swissadme.ch, accessed on 20 April 2025) and ADMET-AI (https://admet.ai.greenstonebio.com, accessed on 21 April 2025) were utilized.

2.4. Prediction of Targets and GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

Following the identification of molecular targets using the SwissTargetPrediction database and manual literature curation for compounds with <5 carbons, like acetate and lactate, which are excluded by this tool, an enrichment analysis was conducted using KEGG and GO databases to explore common targets of Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum selected metabolites and the underlying mechanisms of perinatal depression. ShinyGO 0.76 was used to predict biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions based upon gene ontology (GO) http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/ (accessed on 22 April 2025) (selected with their significant FDR value ≤ 0.05). The main pathways and biological processes, selected based upon fold enrichment, were presented in the form of charts. An integrated analysis was performed using the results of the KEGG analysis to construct a network of potential target proteins linked to the targeted pathologies in our study. This network aimed to elucidate the key role of proteins in the therapeutic effects of metabolites.

2.5. Molecular Docking

2.5.1. Preparation of Ligands and Targets

The three-dimensional (3D) structures of all chosen compounds in SDF format were downloaded from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 25 March 2025) and subsequently converted into PDB files using Open Babel (version 2.4.1). For molecular docking, each ligand was prepared by incorporating Gasteiger charges, adding hydrogen atoms, and optimizing torsional bonds with AutoDock 4.2.6 Tools-1.5.6. The 3D structures of the target proteins—BDNF, CCL2, TNF, IL17A, IL1B, CXCL8, IL6, and IL10—were acquired from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB). These proteins were selected based on our preliminary study, which identified them as key targets for treating perinatal depression [46], and predicted targets using SwissTargetPrediction. To prepare the proteins for docking, heteroatoms and water molecules were removed, polar hydrogen atoms were added, and “Kollman” partial charges were assigned using AutoDock Tools-1.5.6, resulting in final files saved in PDBQT format.

2.5.2. Docking Parameters

To efficiently assess the system’s energy, the AutoDock program employs a three-dimensional potential grid positioned within the protein, covering its active site and allowing the ligand to rotate freely in this region [47,48]. The binding site was defined using a grid box centered on the co-crystallized ligand, with grid dimensions set at a spacing of 0.375 Å (equivalent to a quarter of the length of a C–C bond) around the target protein’s binding site. These settings were saved in a parameter file (with a .gpf extension), which AutoDock uses to compute the affinity between the protein and ligand atoms. The results were output in a text file with a .glg extension.

Subsequently, AutoDock simulated the interactions between ligands and target proteins based on the parameters specified in the .dpf file. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) was applied with its default settings. The .dpf file contained all relevant details about the proteins, ligands, and search algorithm. The outcomes, expressed as interaction energies in kcal/mol, were generated in a text file with a .dlg extension. Ligands exhibiting the lowest binding energy scores were prioritized for further analysis. The docking results were visualized using Discovery Studio software version 2020 (BIOVIA, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Molecular Properties

The bibliographic analysis identified eight key metabolites, as detailed in Table 2. The list includes a variety of compounds such as the short-chain fatty acid acetate (C2H3O2−, MW: 59.04 g/mol), lactate (C3H5O3−, MW: 89.07 g/mol), and formate (CHO2−, MW: 45.02 g/mol). Also identified were essential vitamins and cofactors, including folic acid (C19H19N7O6, MW: 441.40 g/mol), riboflavin (C17H20N4O6, MW: 376.40 g/mol), and vitamin B12 (C63H88CoN14O14P, MW: 1355.40 g/mol). Furthermore, compounds such as kynurenic acid (C10H7NO3, MW: 189.17 g/mol) and ɣ-aminobutyric acid (C4H9NO2, MW: 103.12 g/mol) were also identified.

Table 2.

List of short-chain fatty acids used for molecular docking studies, including their PubChem CID, molecular formula, molecular weight (MW), and SMILES notation.

3.2. Drug-Likeness and Physicochemical Profiling

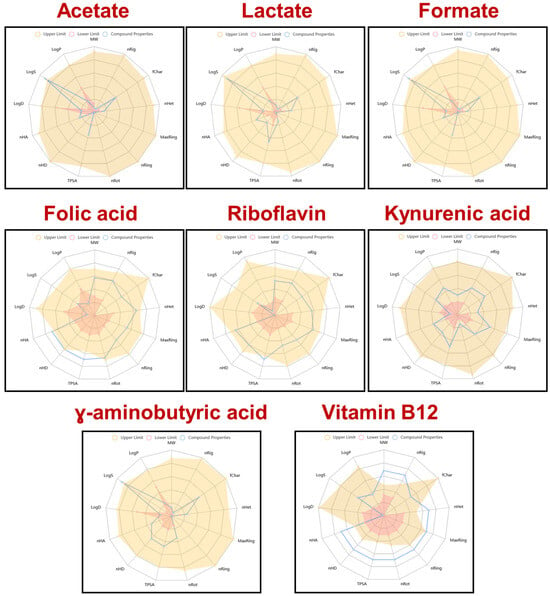

The physicochemical-related properties of eight bioactive molecules, including microbial metabolites (acetate, lactate, formate), dietary vitamins (folic acid, riboflavin, vitamin B12), and neuroactive compounds (kynurenic acid, γ-aminobutyric acid), were evaluated against established drug-likeness criteria (Figure 1). The radar plots illustrate how closely each compound aligns with the acceptable physicochemical space for orally active small molecules. Short-chain fatty acids (acetate, lactate, formate) and γ-aminobutyric acid display minimal structural complexity and fall well within the acceptable boundaries, suggesting good bioavailability and membrane permeability. In contrast, vitamin B12 shows extensive deviation across multiple axes, especially molecular weight (MW), topological polar surface area (TPSA), and hydrogen-bonding parameters, highlighting its poor compliance with conventional drug-likeness rules. Folic acid and riboflavin exhibit moderate deviations, particularly in polarity and hydrogen bonding, reflecting their limited passive absorption and need for carrier-mediated transport. Kynurenic acid aligns relatively well with drug-like profiles, supporting its potential for passive diffusion. These results underscore the importance of physicochemical profiling in predicting the absorption and distribution of bioactive compounds, particularly when evaluating the druggability of naturally occurring microbial or dietary metabolites.

Figure 1.

Radar plots of the physicochemical and drug-likeness properties of selected microbial or dietary metabolites and vitamins, analyzed using ADMETlab 2.0. Each compound is assessed against common drug-likeness criteria based on key molecular descriptors. Blue lines represent the compound’s actual values; shaded areas represent acceptable ranges defined by drug-likeness filters (e.g., Lipinski, Veber, Ghose, Egan, Muegge).

3.3. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) Analysis

3.3.1. Absorption and Distribution

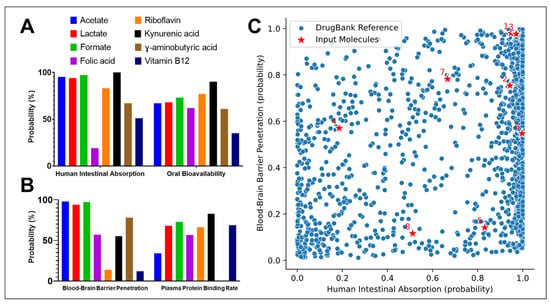

The ADME-related predictions for eight bioactive molecules—acetate, lactate, formate, folic acid, riboflavin, kynurenic acid, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and vitamin B12—focused on their intestinal absorption, bioavailability, blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration, and plasma protein binding potential. Figure 2A shows that short-chain fatty acids (acetate, lactate, and formate) exhibit excellent human intestinal absorption probabilities (>90%), but relatively low oral bioavailability, likely due to rapid metabolism and limited systemic retention. Vitamin B12 and folic acid display lower absorption scores, consistent with their dependence on active transport mechanisms. Kynurenic acid and riboflavin show moderate to high absorption and bioavailability, highlighting their drug-like behavior. The exploration of BBB penetration and plasma protein binding rates showed that Kynurenic acid and GABA demonstrate relatively high probabilities of crossing the BBB, consistent with their known neuroactive roles. In contrast, vitamin B12 and folic acid exhibit very low BBB penetration, reflecting their high molecular weight and polarity. Plasma protein binding is notably high for kynurenic acid and riboflavin, suggesting potential implications for their pharmacokinetics and free active concentrations (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

(A) Human intestinal absorption and oral bioavailability of eight representative metabolites: Acetate, Lactate, Formate, Folic acid, Riboflavin, Kynurenic acid, γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), and Vitamin B12; (B) Probability of blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetration and plasma protein binding rates of the same metabolites; (C) Scatter plot representing the comparative pharmacokinetic profile of the studied metabolites (1–8) corresponding to the compounds listed in Table 1 (red stars) versus DrugBank reference compounds (blue dots), according to human intestinal absorption (x-axis) and BBB penetration (y-axis). Numbers label individual input metabolites.

Finally, Figure 2C compares the predicted human intestinal absorption and BBB penetration probabilities of the input molecules (red stars) against a reference dataset of approved drugs from DrugBank (blue dots). The distribution confirms that most input molecules fall within biologically relevant zones, although some, like vitamin B12, are outliers with poor passive absorption and BBB permeability. Collectively, these results highlight the diversity in pharmacokinetic behavior among small endogenous or dietary compounds, with key implications for their systemic availability and therapeutic potential.

3.3.2. Metabolism and Excretion

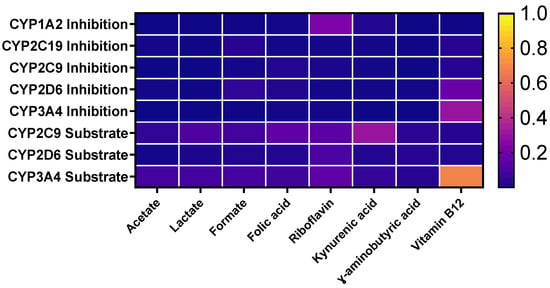

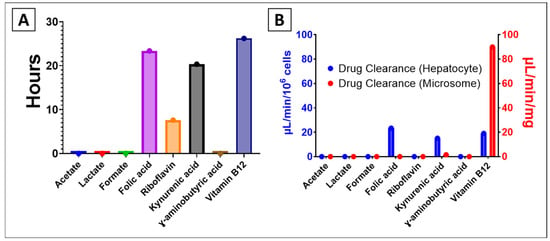

The prediction of metabolism of the 8 metabolites showed substantial variability in their predicted interactions with key cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms. This heatmap illustrates the probability scores for each compound acting as a substrate or inhibitor of major human CYP enzymes, including CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4. Short-chain fatty acids (acetate, lactate, and formate) exhibit minimal interaction with CYP enzymes, reflected by very low probability scores across all isoforms, suggesting they are neither metabolized by nor interfere with major CYP pathways. Similarly, γ-aminobutyric acid and kynurenic acid display weak or negligible interaction potential, indicating limited metabolism through hepatic CYPs. In contrast, folic acid, riboflavin, and particularly vitamin B12 show higher probability values, suggesting a greater likelihood of involvement in CYP-mediated metabolism. Notably, vitamin B12 demonstrates the highest interaction probability with CYP3A4, a key enzyme responsible for metabolizing a broad spectrum of xenobiotics and endogenous compounds. This may reflect the complexity of B12’s biotransformation pathways or its potential to modulate CYP activity indirectly (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Heat map representing the probability of metabolism of the selected metabolites by different CYP enzymes and predictive results of excretion of selected metabolites.

The half-life of the selected metabolites, on the other hand, showed significant variation across compounds (Figure 4A). While acetate, lactate, and formate exhibited very short half-lives (close to 0 h), folic acid, riboflavin, and vitamin B12 displayed markedly longer persistence, with half-lives exceeding 20 h. Kynurenic acid and GABA showed intermediate stability, around 10–20 h.

Figure 4.

Predicted results of (A) half-life and (B) hepatocyte and microsome drug clearance of selected metabolites.

In contrast, the probability of drug clearance (Figure 4B) revealed compound-specific patterns depending on the system used. In hepatocyte-based assays (blue), kynurenic acid (15.09 µL/min/106 cells), vitamin B12 (19.05 µL/min/106 cells), and folic acid (23.36 µL/min/106 cells) had the highest clearance rates, while most small metabolites showed minimal clearance. In microsomal assays (red), vitamin B12 displayed a notably high clearance (89.97 µL/min/mg), indicating its rapid biotransformation potential in microsomal systems compared to other metabolites.

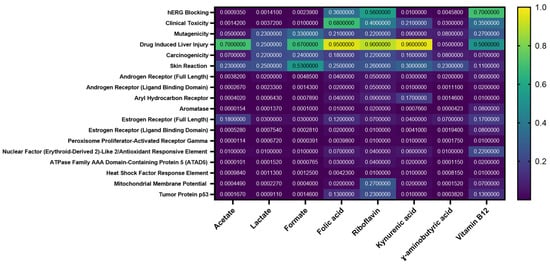

3.4. Toxicity Prediction

The predicted probabilities of toxicity in humans across various parameters, particularly focusing on drug-induced liver injury (DILI), were assessed. The values range from very low to medium probabilities, with the color gradient indicating the severity of the predicted toxicity (Figure 5). Among the parameters assessed, drug-induced liver injury shows a medium probability for certain compounds, suggesting a potential concern for hepatotoxicity associated with these substances. This medium probability indicates that, while the risk is not the highest, there may be a noteworthy chance of adverse effects on liver function, warranting further evaluation in the context of drug safety and efficacy (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Heat map of the probability of toxic properties of the selected metabolites (Acetate, Lactate, Formate, Folic acid, Riboflavin, Kynurenic acid, γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), and Vitamin B12).

The other values in the heatmap also reflect varying probabilities of toxicity, with some parameters exhibiting low probabilities, indicating a reduced likelihood of adverse effects.

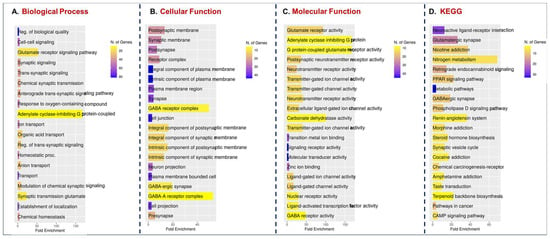

3.5. Enrichment Analysis

The enrichment analysis shown in the figure presents the biological, cellular, and molecular functions, as well as KEGG pathways, associated with the predicted targets of eight metabolites from Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum. These findings are particularly relevant in the context of perinatal depression, a complex neuropsychiatric condition with multifactorial etiology involving neurotransmitter imbalances, inflammation, and hormonal fluctuations.

3.5.1. Biological Processes, Cellular Components and Molecular Functions

The enriched biological processes reveal a strong involvement in synaptic signaling, especially glutamatergic and GABAergic pathways, which are known to be disrupted in depression. The glutamate receptor signaling pathway and adenylate cyclase-inhibiting G protein-coupled receptor signaling pathway are both highlighted, suggesting an influence on excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission. Also enriched are processes related to chemical synaptic transmission, trans-synaptic signaling, and cell–cell signaling, all critical for neuronal communication. These pathways are deeply implicated in the neurobiology of depression and antidepressant response (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Fold enrichment analysis results of (A) Biological processes, (B) Cellular components, (C) Molecular functions and (D) KEGG pathways from the combined target list of all analyzed compounds.

From a structural perspective, most targets are localized in the postsynaptic membrane, synaptic regions, and GABA receptor complexes. Notably, enrichment in GABA-A receptor complex suggests a direct modulation of GABAergic inhibitory tone, often reduced in depression and anxiety disorders. The presence of plasma membrane, intrinsic membrane components, and neuronal projections indicates that the microbial metabolites may act on synaptic transmission through receptor-level interactions and modulation of neuronal excitability (Figure 6B).

The molecular function analysis reinforces the biological relevance of these metabolites in neuropsychiatric modulation. Enriched terms include glutamate receptor activity, GABA receptor activity, transmitter-gated ion channel activity, and G protein-coupled glutamate receptor activity. This suggests that microbial metabolites might mimic or modulate neurotransmitter signaling, potentially normalizing the imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory signals often reported in perinatal depression (Figure 6C). Other enriched functions include carbonic anhydrase activity and ligand-gated ion channel activity, both of which are involved in neurophysiological regulation and pH balance in the brain.

3.5.2. KEGG Pathways Results

KEGG analysis identifies critical pathways such as neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, glutamatergic and GABAergic synapse, and nicotine addiction, indicating overlapping mechanisms with known psychiatric conditions. Interestingly, pathways related to PPAR signaling, renin-angiotensin system, steroid biosynthesis, and nitrogen metabolism were also enriched, suggesting that these metabolites may influence inflammation, oxidative stress, and neuroendocrine balance of key factors in perinatal depression pathogenesis (Figure 6D).

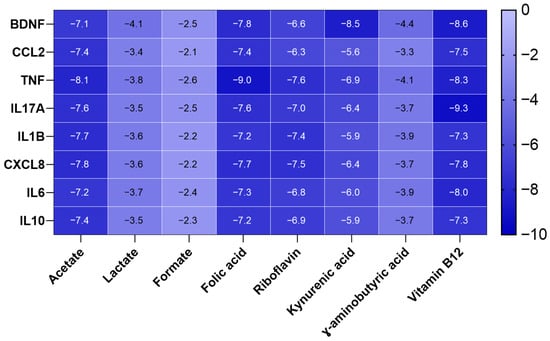

3.6. Prediction of Interactions by Molecular Docking

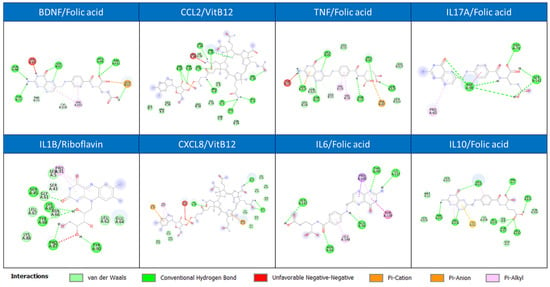

Based on the highly negative docking scores (down to −9.3) (Figure 7), the interactions between the cytokines and vitamins are exceptionally stable, indicating strong binding affinity. The results are characterized by key stabilizing forces, most notably Conventional Hydrogen Bonds, which ensure specific and tight binding.

Figure 7.

Molecular docking scores of the selected metabolites (Acetate, Lactate, Formate, Folic acid, Riboflavin, Kynurenic acid, γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA), and Vitamin B12) with the identified targets (BDNF, CCL2, TNF, IL17A, IL1B, CXCL8, IL6, IL10).

Additional stability is provided by Pi-interactions (Pi-Cation, Pi-Anion, Pi-Alkyl) (Figure 8), suggesting aromatic amino acid residues in the binding pocket are crucial for engaging with the ligands. The significant contribution of van der Waals forces further promotes close molecular complementarity.

Figure 8.

Discovery Studio visualization of one of the most stable interactions for each selected target (BDNF, CCL2, TNF, IL17A, IL1B, CXCL8, IL6, IL10).

The lack of repulsive Unfavorable Negative-Negative interactions confirms the compatibility of the binding partners. Visualized in Discovery Studio, the most stable complex would show the ligand deeply buried within a pocket, engaged in a network of these simultaneous hydrogen and pi-based interactions, explaining the highly favorable binding energy.

4. Discussion

Perinatal depression (PND) represents a significant public health challenge, with profound implications for maternal and infant well-being [49]. The complex interplay of hormonal fluctuations, genetic predisposition, and neuroinflammation in its pathophysiology necessitates novel therapeutic approaches [2,3]. This study employed a comprehensive in silico framework to evaluate the therapeutic potential of key metabolites derived from the probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum for targeting PND (Table 2).

Our computational findings suggest that these microbial metabolites possess favorable pharmacokinetic profiles and exhibit strong binding affinities towards critical proteins involved in neuroinflammation, neuroendocrinology, and synaptic plasticity, positioning them as promising neuroactive agents.

The initial ADMET profiling revealed a clear distinction between the simpler microbial metabolites and the more complex vitamins. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, lactate, and formate, along with neuroactive compounds such as GABA and kynurenic acid, demonstrated excellent predicted human intestinal absorption (>90%), aligning with known physiology where SCFAs are rapidly absorbed via colonocytes through monocarboxylate transporters [50]. Their minimal interaction with cytochrome P450 enzymes suggests a low potential for pharmacokinetic drug–drug interactions, a significant advantage for use in perinatal populations where polypharmacy is a concern [51,52]. Conversely, the structurally complex vitamins B12 and folic acid showed poor passive absorption and BBB penetration, consistent with their known dependence on specific active transport mechanisms (e.g., intrinsic factor for B12) [53]. This underscores that while these vitamins are crucial, their direct central effects may be limited without these transporters, whereas SCFAs and other small metabolites may more readily exert systemic and central effects.

A critical finding of this study is the predicted ability of several metabolites to cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Specifically, kynurenic acid and GABA showed relatively high BBB penetration probabilities. This is physiologically coherent, as GABA transporters are present at the BBB [54], and kynurenic acid, an endogenous NMDA receptor antagonist, is known to play a role in central nervous system signaling [55]. The ability of these microbiota-derived compounds to potentially access the brain is a cornerstone of the gut–brain axis hypothesis and suggests they could directly modulate central pathways implicated in PND.

The enrichment analysis provided a systems-level view of the biological mechanisms likely modulated by these metabolites. The significant enrichment of terms related to glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic signaling is particularly relevant. An imbalance between excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) neurotransmission is a well-established feature of major depression, and this is increasingly recognized in PND [56]. The prediction that these microbial metabolites can influence glutamate receptor activity, GABA receptor complex function, and transmitter-gated ion channel activity suggests a potential mechanism for restoring this neurochemical equilibrium. For instance, L. helveticus-produced GABA could directly enhance inhibitory tone by acting on GABA-A receptors, while kynurenic acid from B. longum could dampen excessive glutamatergic activity via NMDA receptor antagonism [57].

Furthermore, the enrichment of KEGG pathways such as neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction and PPAR signaling provides additional mechanistic insights. PPARγ activation, for example, has demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antidepressant effects in preclinical models by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production [58]. SCFAs like butyrate are known agonists of PPARγ [59], suggesting a pathway through which these metabolites could ameliorate the neuroinflammatory component often observed in PND. The enrichment of the renin-angiotensin system pathway is also intriguing, as recent evidence links brain angiotensin II to stress, anxiety, and neuroinflammation, and its modulation may offer a novel therapeutic avenue [60].

The molecular docking results offer a structural basis for these predicted activities. The strong binding affinities (highly negative docking scores) observed between the metabolites and key targets like TNF, IL-6, and BDNF are compelling. The high stability of these complexes, driven by conventional hydrogen bonds and Pi-interactions, suggests that metabolites like kynurenic acid or specific SCFAs could act as direct inhibitors of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IL-6. Chronic neuroinflammation, characterized by elevated levels of these cytokines, is strongly associated with depressive symptoms and is a proposed mechanism in PND [61]. By potentially inhibiting these cytokines, the metabolites could disrupt a vicious cycle where inflammation contributes to depressive symptoms, which in turn can exacerbate inflammatory responses.

Similarly, the strong interaction with Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) is of paramount importance. BDNF is a key mediator of neuroplasticity, neuronal survival, and synaptic maturation. Reduced BDNF levels have been consistently reported in depression and are thought to contribute to the structural and functional changes in brain regions like the hippocampus [62]. The potential of microbial metabolites to interact with and possibly stabilize BDNF could support neurogenesis and synaptic resilience, countering the neurotoxic effects of stress and inflammation prevalent in PND [63].

5. Conclusions and Limitations

In conclusion, this integrative in silico study provides a strong theoretical foundation for the therapeutic application of L. helveticus and B. longum metabolites in perinatal depression. Our results suggest that key compounds, particularly SCFAs, kynurenic acid, and GABA, exhibit favorable drug-like properties and are predicted to concurrently modulate core pathological features of PND through a multi-target mechanism. However, these promising findings must be interpreted within the context of several important limitations. Firstly, the production of neuroactive metabolites like acetate, GABA, and folate is not an exclusive property of the studied strains but is a widespread function across the gut microbiota. The proposed psychobiotic effects may therefore represent a collective, synergistic output of the microbial community, where other efficient producers, such as Lactobacillus salivarius or Lactobacillus ruminis, could play an equally significant or complementary role. Most critically, our computational predictions, while powerful for prioritization and hypothesis generation, are not a substitute for experimental validation. The complex dynamics of the gut environment, along with critical in vivo pharmacokinetic hurdles, including true systemic bioavailability, metabolic stability, and effective blood–brain barrier penetration, remain to be empirically confirmed. Future work must therefore focus on in vitro and in vivo studies to translate these compelling in silico insights into validated, microbiome-based interventions for this debilitating disorder.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A. and W.T.; methodology, O.A., W.T. and C.S.; software, W.T.; validation, F.B. and F.C.; formal analysis, W.T. and C.S.; data curation, W.T. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A. and W.T.; writing—review and editing, H.A., I.F., I.T., F.B. and F.C.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, F.B. and F.C.; project administration, W.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| CCL2 | C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 2 (also known as MCP-1) |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CXCL8 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 8 (also known as IL-8) |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6) |

| DILI | Drug-Induced Liver Injury |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GABA | γ-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| hERG | Human Ether-à-go-go-Related Gene (a potassium ion channel, critical for cardiotoxicity screening) |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase |

| IL1B | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IGF2 | Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LGA | Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| NR3C1 | Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 3 Group C Member 1 (Glucocorticoid Receptor) |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| PDBQT | Protein Data Bank, Partial Charge (Q), & Atom Type (T) |

| PND | Perinatal Depression |

| POMC | Pro-opiomelanocortin |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| SMILES | Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System |

| SSRIs | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors |

| TDO | Tryptophan 2,3-Dioxygenase |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| TPSA | Topological Polar Surface Area |

References

- Dagher, R.K.; Bruckheim, H.E.; Colpe, L.J.; Edwards, E.; White, D.B. Perinatal Depression: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Women’s Health 2021, 30, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupanagunta, G.P.; Nandave, M.; Rawat, D.; Upadhyay, J.; Rashid, S.; Ansari, M.N. Postpartum depression: Aetiology, pathogenesis and the role of nutrients and dietary supplements in prevention and management. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 1274–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, I.S.; Tanner Stapleton, L.R.; Guardino, C.M.; Hahn-Holbrook, J.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: Systematic review and call for integration. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 99–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frieder, A.; Fersh, M.; Hainline, R.; Deligiannidis, K.M. Pharmacotherapy of Postpartum Depression: Current Approaches and Novel Drug Development. CNS Drugs 2019, 33, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socała, K.; Doboszewska, U.; Szopa, A.; Serefko, A.; Włodarczyk, M.; Zielińska, A.; Poleszak, E.; Fichna, J.; Wlaź, P. The role of microbiota-gut-brain axis in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 172, 105840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portincasa, P.; Bonfrate, L.; Vacca, M.; De Angelis, M.; Farella, I.; Lanza, E.; Khalil, M.; Wang, D.Q.; Sperandio, M.; Di Ciaula, A. Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids: Implications in Glucose Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, K.J.; Collins, M.K.; Moloney, G.M.; Knox, E.G.; Aburto, M.R.; Fülling, C.; Morley, S.J.; Clarke, G.; Schellekens, H.; Cryan, J.F. Short chain fatty acids: Microbial metabolites for gut-brain axis signalling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2022, 546, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Hu, H.; Ju, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y. Gut microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids and depression: Deep insight into biological mechanisms and potential applications. Gen. Psychiatry 2024, 37, e101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romijn, A.R.; Rucklidge, J.J.; Kuijer, R.G.; Frampton, C. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Lactobacillus helveticus and Bifidobacterium longum for the symptoms of depression. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2017, 51, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohland, C.L.; Kish, L.; Bell, H.; Thiesen, A.; Hotte, N.; Pankiv, E.; Madsen, K.L. Effects of Lactobacillus helveticus on murine behavior are dependent on diet and genotype and correlate with alterations in the gut microbiome. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 1738–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawa, D.; Laczmanski, L.; Budrewicz, S.; Pokryszko-Dragan, A.; Podbielska, M. Targeting gut microbiota: New therapeutic opportunities in multiple sclerosis. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2274126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamba, R.R.; Yamamoto, S.; Abdel-Hamid, M.; Sasaki, T.; Michihata, T.; Koyanagi, T.; Enomoto, T. Chemical, Microbiological, and Functional Characterization of Kefir Produced from Cow’s Milk and Soy Milk. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 7019286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, H.E.; Vaughan, F. Elucidation of the Inhibitory Factors of Yogurt against Salmonella typhimurium. J. Dairy Sci. 1979, 62, 1873–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Wu, W.; Chen, L.; Yang, W.; Huang, X.; Ma, C.; Chen, F.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, C.; et al. Microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids promote Th1 cell IL-10 production to maintain intestinal homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Kang, S.G.; Park, J.H.; Yanagisawa, M.; Kim, C.H. Short-Chain Fatty Acids Activate GPR41 and GPR43 on Intestinal Epithelial Cells to Promote Inflammatory Responses in Mice. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 396–406.e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, D. Physicochemical, colour, microbiology, sensory and mineral attributes of set-type yoghurt produced from Gundelia tournefortii L. and its gum. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 2166–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.W.; Tellez, A.M. Lactobacillus helveticus: The proteolytic system. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintsis, T. Lactic acid bacteria as starter cultures: An update in their metabolism and genetics. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 665–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.D.; Bradley, S.; Buckley, N.D.; Green-Johnson, J.M. Interactions of lactic acid bacteria with human intestinal epithelial cells: Effects on cytokine production. J. Food Prot. 2003, 66, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearps, A.C.; Tyssen, D.; Srbinovski, D.; Bayigga, L.; Diaz, D.J.D.; Aldunate, M.; Cone, R.A.; Gugasyan, R.; Anderson, D.J.; Tachedjian, G. Vaginal lactic acid elicits an anti-inflammatory response from human cervicovaginal epithelial cells and inhibits production of pro-inflammatory mediators associated with HIV acquisition. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, R.; Fujisawa, M.; Koyanagi, S.; Muramatsu, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Wada, Y.; Akama, K.; Tanaka, M.; Kurashige, H.; Sato, A.; et al. Formate-producing capacity provided by reducing ability of Streptococcus thermophilus nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidase determines yogurt acidification rate. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 6710–6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, J.; Kawai, Y.; Aritomo, R.; Ito, Y.; Makino, S.; Ikegami, S.; Isogai, E.; Saito, T. Effect of Formic Acid on Exopolysaccharide Production in Skim Milk Fermentation by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus OLL1073R-1. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2013, 32, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, H.; Sasaki, Y. Short communication: Effect of oxygen on symbiosis between Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 2904–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, E.R.; Winter, M.G.; Duerkop, B.A.; Spiga, L.; Furtado de Carvalho, T.; Zhu, W.; Gillis, C.C.; Büttner, L.; Smoot, M.P.; Behrendt, C.L.; et al. Microbial Respiration and Formate Oxidation as Metabolic Signatures of Inflammation-Associated Dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompei, A.; Cordisco, L.; Amaretti, A.; Zanoni, S.; Matteuzzi, D.; Rossi, M. Folate production by bifidobacteria as a potential probiotic property. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sybesma, W.; Starrenburg, M.; Tijsseling, L.; Hoefnagel, M.H.; Hugenholtz, J. Effects of cultivation conditions on folate production by lactic acid bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 4542–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnowska-Kujawska, M.; Paszczyk, B. Changes in the Folate Content and Fatty Acid Profile in Fermented Milk Produced with Different Starter Cultures during Storage. Molecules 2021, 26, 6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Mei, J.; Gong, Q. Role of Folate in Liver Diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöpping, M.; Gaspar, P.; Neves, A.R.; Franzén, C.J.; Zeidan, A.A. Identifying the essential nutritional requirements of the probiotic bacteria Bifidobacterium animalis and Bifidobacterium longum through genome-scale modeling. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2021, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solopova, A.; Bottacini, F.; Venturi Degli Esposti, E.; Amaretti, A.; Raimondi, S.; Rossi, M.; van Sinderen, D. Riboflavin Biosynthesis and Overproduction by a Derivative of the Human Gut Commensal Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 573335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutinel Evan, D.; Dean Antony, M.; Gralnick Jeffrey, A. Description of a Riboflavin Biosynthetic Gene Variant Prevalent in the Phylum Proteobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 5479–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwannasom, N.; Kao, I.; Pruß, A.; Georgieva, R.; Bäumler, H. Riboflavin: The Health Benefits of a Forgotten Natural Vitamin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waclawiková, B.; El Aidy, S. Role of Microbiota and Tryptophan Metabolites in the Remote Effect of Intestinal Inflammation on Brain and Depression. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, Q.; Chen, Q.; Mao, X.; Wang, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Bifidobacterium longum CCFM1077 Ameliorated Neurotransmitter Disorder and Neuroinflammation Closely Linked to Regulation in the Kynurenine Pathway of Autistic-like Rats. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirthgen, E.; Hoeflich, A.; Rebl, A.; Günther, J. Kynurenic Acid: The Janus-Faced Role of an Immunomodulatory Tryptophan Metabolite and Its Link to Pathological Conditions. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, M.C.; Elmer, G.I.; Bergeron, R.; Albuquerque, E.X.; Guidetti, P.; Wu, H.-Q.; Schwarcz, R. Reduction of Endogenous Kynurenic Acid Formation Enhances Extracellular Glutamate, Hippocampal Plasticity, and Cognitive Behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010, 35, 1734–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszaki, J.; Palásthy, Z.; Erczes, D.; Rácz, A.; Torday, C.; Varga, G.; Vécsei, L.; Boros, M. Kynurenic acid inhibits intestinal hypermotility and xanthine oxidase activity during experimental colon obstruction in dogs. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2008, 20, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokovic Bajic, S.; Djokic, J.; Dinic, M.; Veljovic, K.; Golic, N.; Mihajlovic, S.; Tolinacki, M. GABA-Producing Natural Dairy Isolate From Artisanal Zlatar Cheese Attenuates Gut Inflammation and Strengthens Gut Epithelial Barrier in vitro. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunes, R.A.; Poluektova, E.U.; Dyachkova, M.S.; Klimina, K.M.; Kovtun, A.S.; Averina, O.V.; Orlova, V.S.; Danilenko, V.N. GABA production and structure of gadB/gadC genes in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains from human microbiota. Anaerobe 2016, 42, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Law, Y.-S.; Shah, N.P. Dairy Streptococcus thermophilus improves cell viability of Lactobacillus brevis NPS-QW-145 and its γ-aminobutyric acid biosynthesis ability in milk. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, M.; Lalonde, R.; Violle, N.; Javelot, H.; Desor, D.; Nejdi, A.; Bisson, J.F.; Rougeot, C.; Pichelin, M.; Cazaubiel, M.; et al. Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 105, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindjau, R.; Chua, J.-Y.; Liu, S.-Q. Growth and metabolic behavior of probiotic Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum in minimally supplemented soy (tofu) whey. Future Foods 2023, 8, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rätsep, M.; Kilk, K.; Zilmer, M.; Kuus, L.; Songisepp, E. A Novel Bifidobacterium longum ssp. longum Strain with Pleiotropic Effects. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Sha, Y.; Chamlagain, B.; Edelmann, M.; Savijoki, K.; Piironen, V.; Deptula, P.; Varmanen, P. Oxygen determines the requirement for cobalamin but not riboflavin in the growth of Propionibacterium freudenreichii. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarenhas, R.; Ruetz, M.; Gouda, H.; Heitman, N.; Yaw, M.; Banerjee, R. Architecture of the human G-protein-methylmalonyl-CoA mutase nanoassembly for B12 delivery and repair. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wafaa, T.; Oumaima, A.; Amine, T.; Chaimaa, S.; Mariame El, M.; Faiza, B.; Fatima, C. Integrative Analysis of the Impact of Prenatal Depression on the Newborn Intestinal Microbiota. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 25, 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forli, S.; Huey, R.; Pique, M.E.; Sanner, M.F.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. Computational protein-ligand docking and virtual drug screening with the AutoDock suite. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahnou, H.; Hmimid, F.; Errami, A.; Nait Irahal, I.; Limami, Y.; Oudghiri, M. Integrating ADMET, enrichment analysis, and molecular docking approach to elucidate the mechanism of Artemisia herba alba for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease-associated arthritis. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A 2024, 87, 836–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharoy, R.; Potdukhe, A.; Wanjari, M.; Taksande, A.B. Postpartum Depression and Maternal Care: Exploring the Complex Effects on Mothers and Infants. Cureus 2023, 15, e41381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Besten, G.; van Eunen, K.; Groen, A.K.; Venema, K.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Bakker, B.M. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 2325–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, U.M.; Schwab, M. Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: Regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 138, 103–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.; Phillips, K.; Subramanian, A.; Lee, S.I.; Wang, Z.; McCowan, R.; Agrawal, U.; Fagbamigbe, A.F.; Nelson-Piercy, C.; Brocklehurst, P.; et al. Prevalence of polypharmacy in pregnancy: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infante, M.; Leoni, M.; Caprio, M.; Fabbri, A. Long-term metformin therapy and vitamin B12 deficiency: An association to bear in mind. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 916–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Danbolt, N.C. GABA and Glutamate Transporters in Brain. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majláth, Z.; Török, N.; Toldi, J.; Vécsei, L. Memantine and Kynurenic Acid: Current Neuropharmacological Aspects. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Altered Connectivity in Depression: GABA and Glutamate Neurotransmitter Deficits and Reversal by Novel Treatments. Neuron 2019, 102, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Alkondon, M.; Albuquerque, E.X. Kynurenic acid inhibits glutamatergic transmission to CA1 pyramidal neurons via α7 nAChR-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 84, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Shi, L.; Xin, W.; Xu, J.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Yao, W.; et al. Activation of PPARγ inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines production by upregulation of miR-124 in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 486, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, P.; Shen, L.; Niu, L.; Tan, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, L.; Hao, X.; Li, X.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Association with Signalling Pathways in Inflammation, Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villapol, S.; Janatpour, Z.C.; Affram, K.O.; Symes, A.J. The Renin Angiotensin System as a Therapeutic Target in Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1565–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassamal, S. Chronic stress, neuroinflammation, and depression: An overview of pathophysiological mechanisms and emerging anti-inflammatories. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1130989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, Z.Y. The role of BDNF in depression on the basis of its location in the neural circuitry. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2011, 32, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molska, M.; Mruczyk, K.; Cisek-Woźniak, A.; Prokopowicz, W.; Szydełko, P.; Jakuszewska, Z.; Marzec, K.; Trocholepsza, M. The Influence of Intestinal Microbiota on BDNF Levels. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.