Discovery and Activity Evaluation of Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors from an Endophytic Bacillus Strain W10-B1 Isolated from Coelothrix irregularis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Regents, Strains, and Instrument

2.2. Strain Isolation and Identification

2.3. Large-Scale Cultivation, Extraction, and Isolation

2.4. Screening for Anti-Quorum-Sensing Activity

2.5. Growth Curve Analysis

2.6. Motility Assays

2.7. Biofilm Formation Assay

2.8. Determination of Viable Bacteria in Biofilm by Colony Counting

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

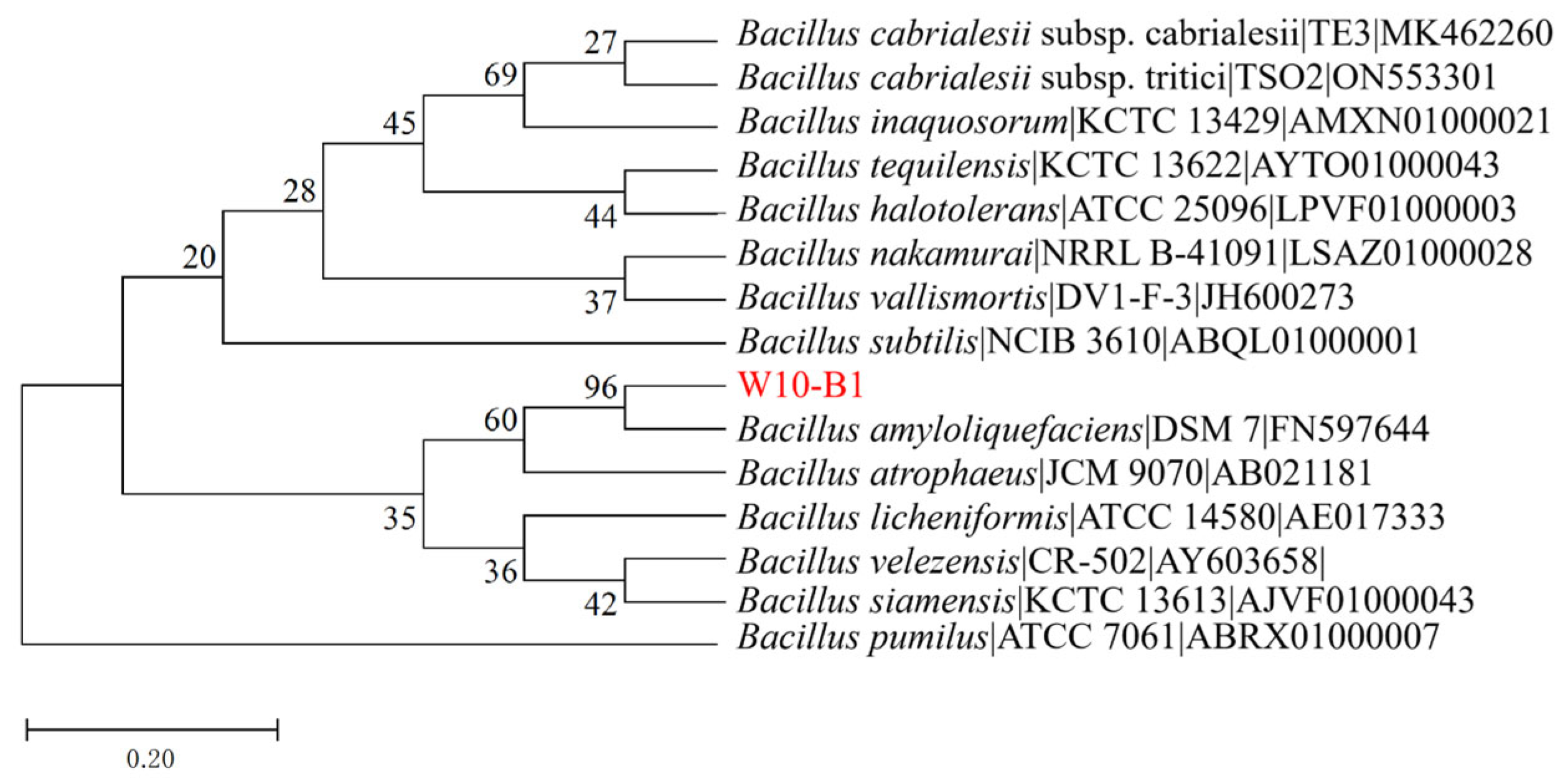

3.1. Strain Identification

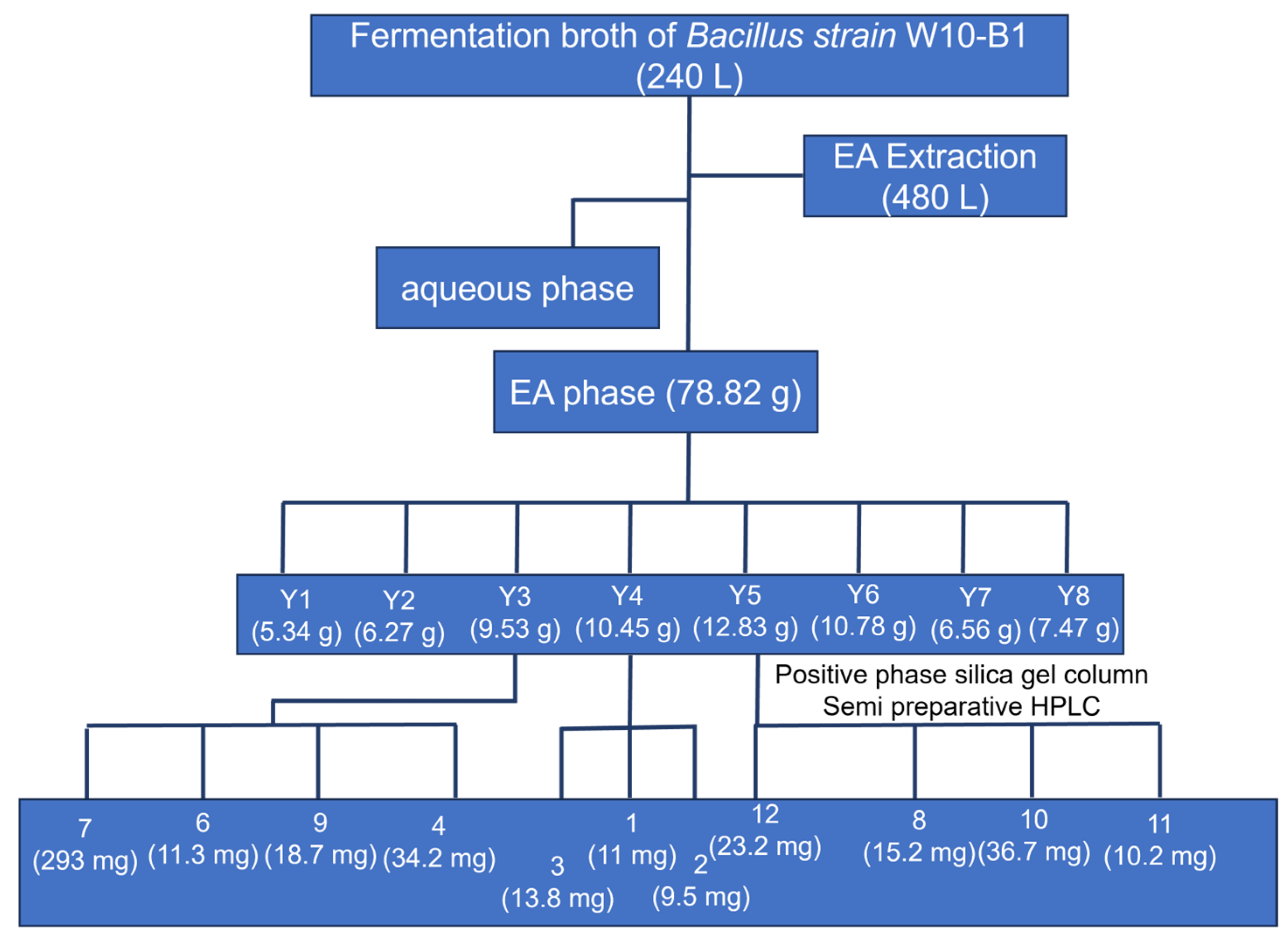

3.2. Results of Compound Isolation and Purification

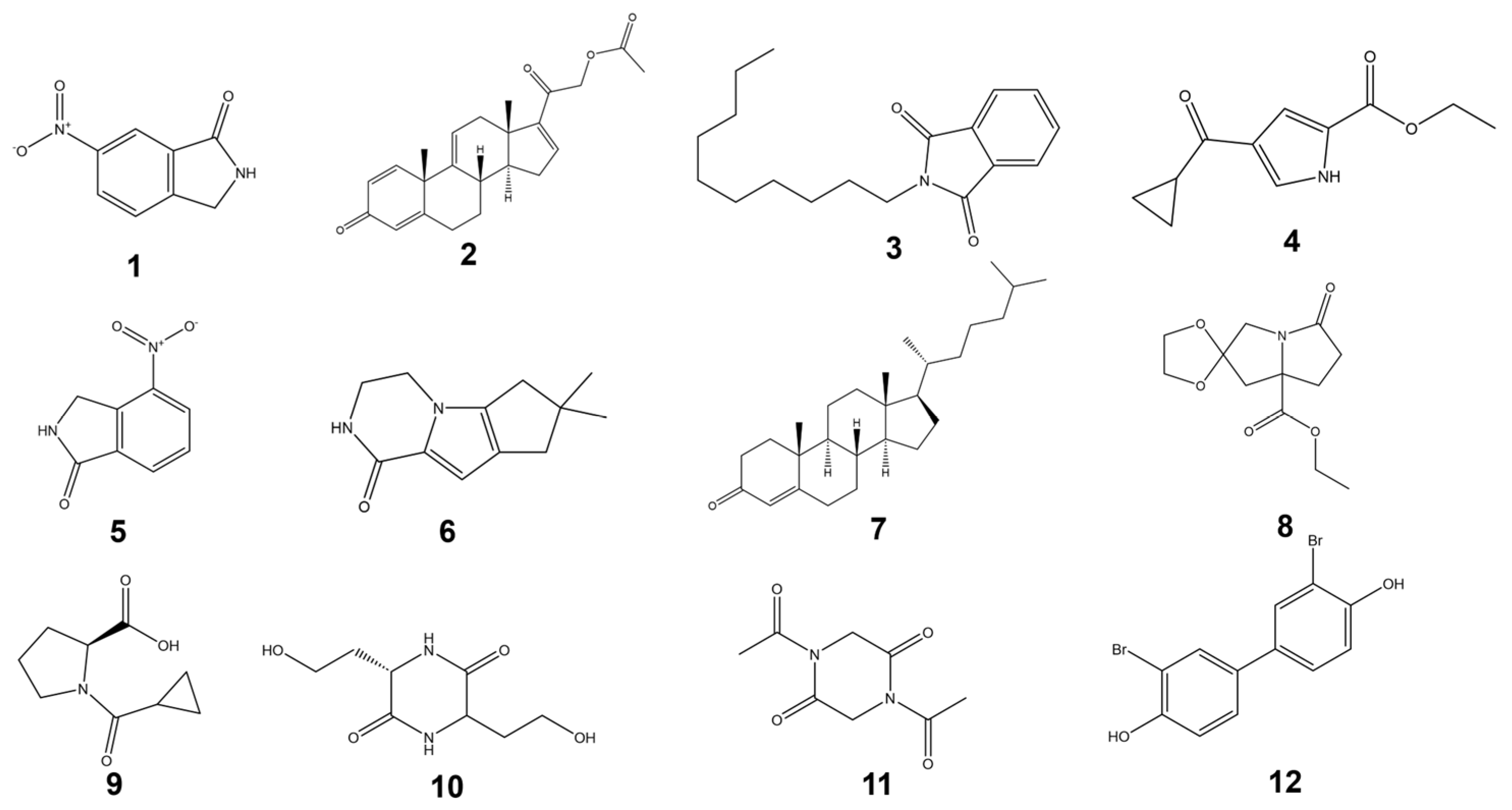

3.3. Structural Elucidation of Compounds

3.4. Screening for QSI Compounds

3.5. Quorum-Sensing Inhibitory Activity of 3,3′-Dibromo-4,4′-Biphenyldiol Against S. marcescens NJ01

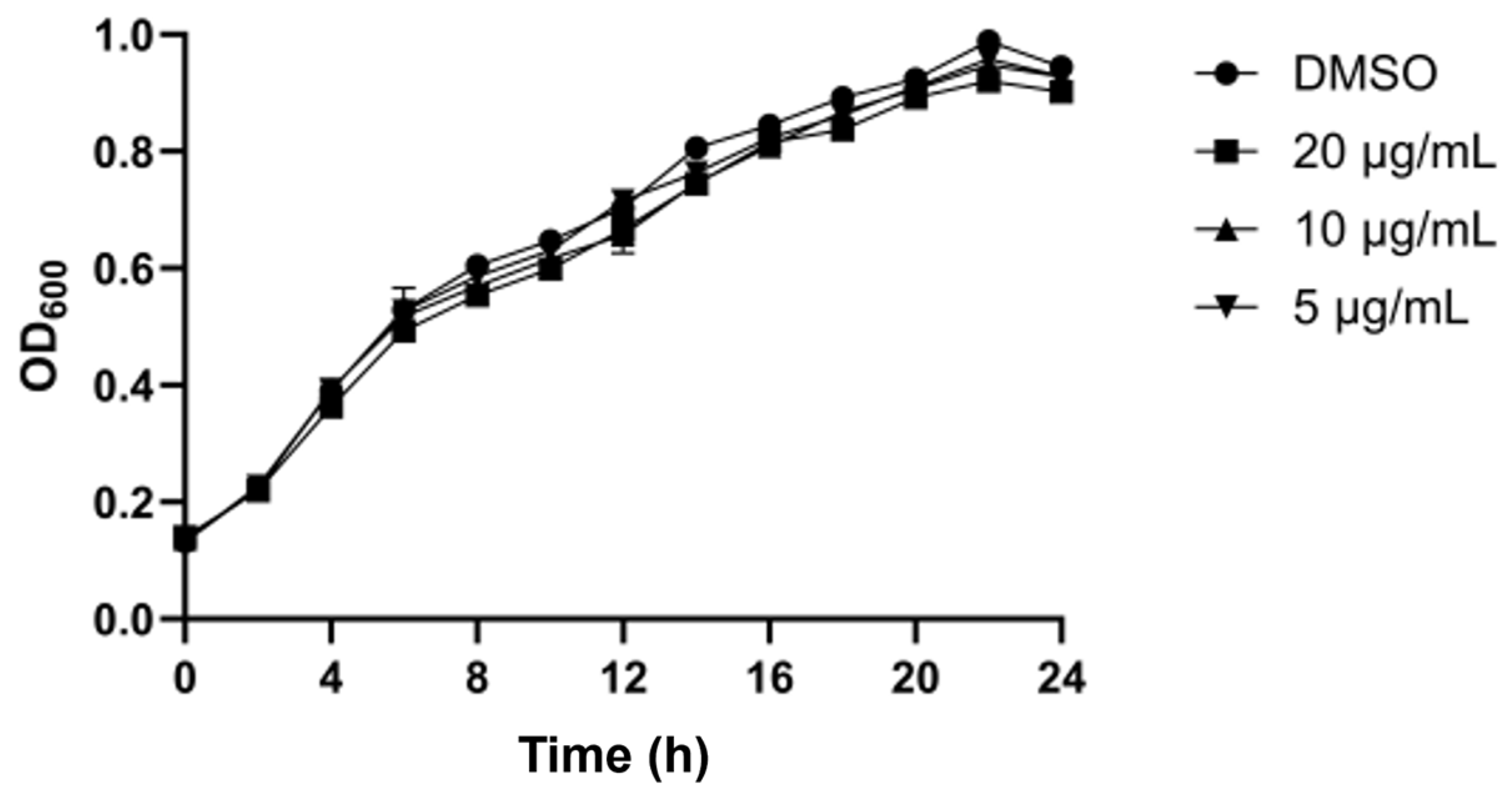

3.5.1. Growth Curve

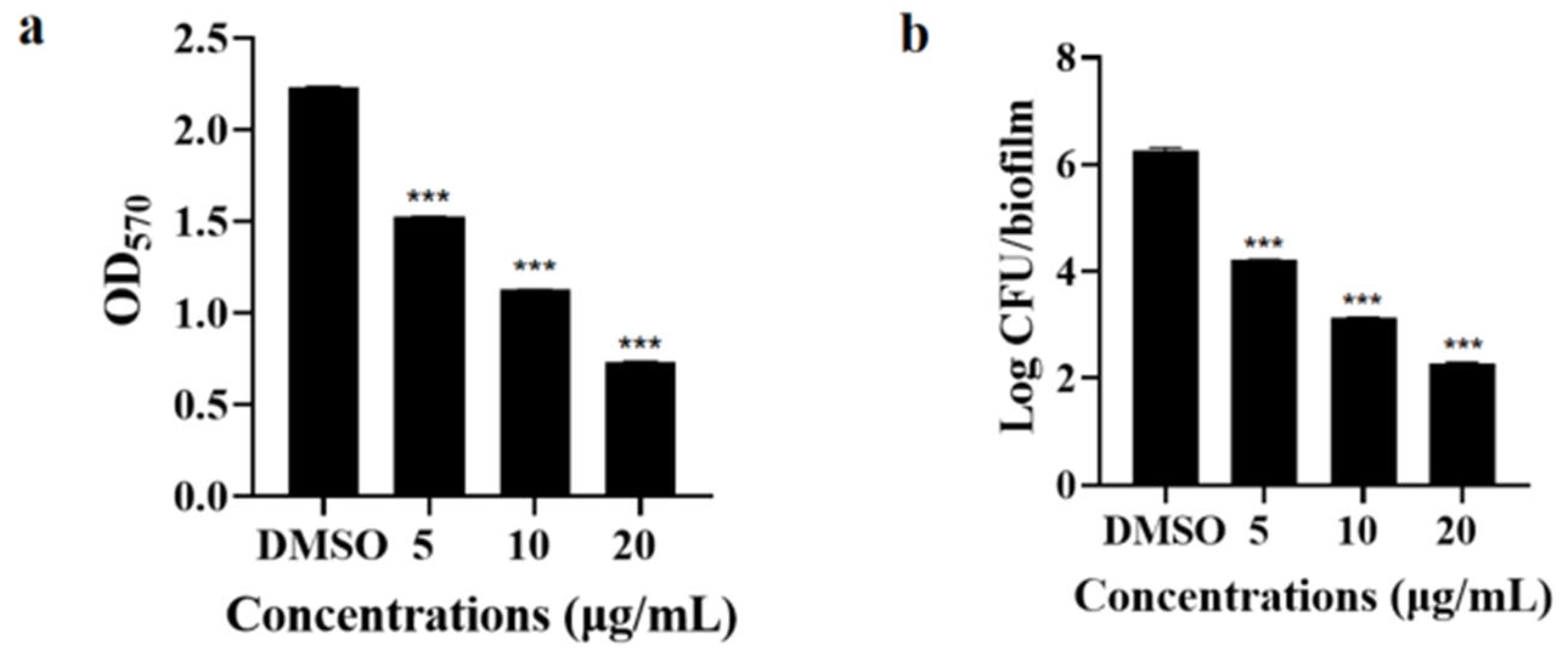

3.5.2. Inhibitory Effect on Biofilm Formation

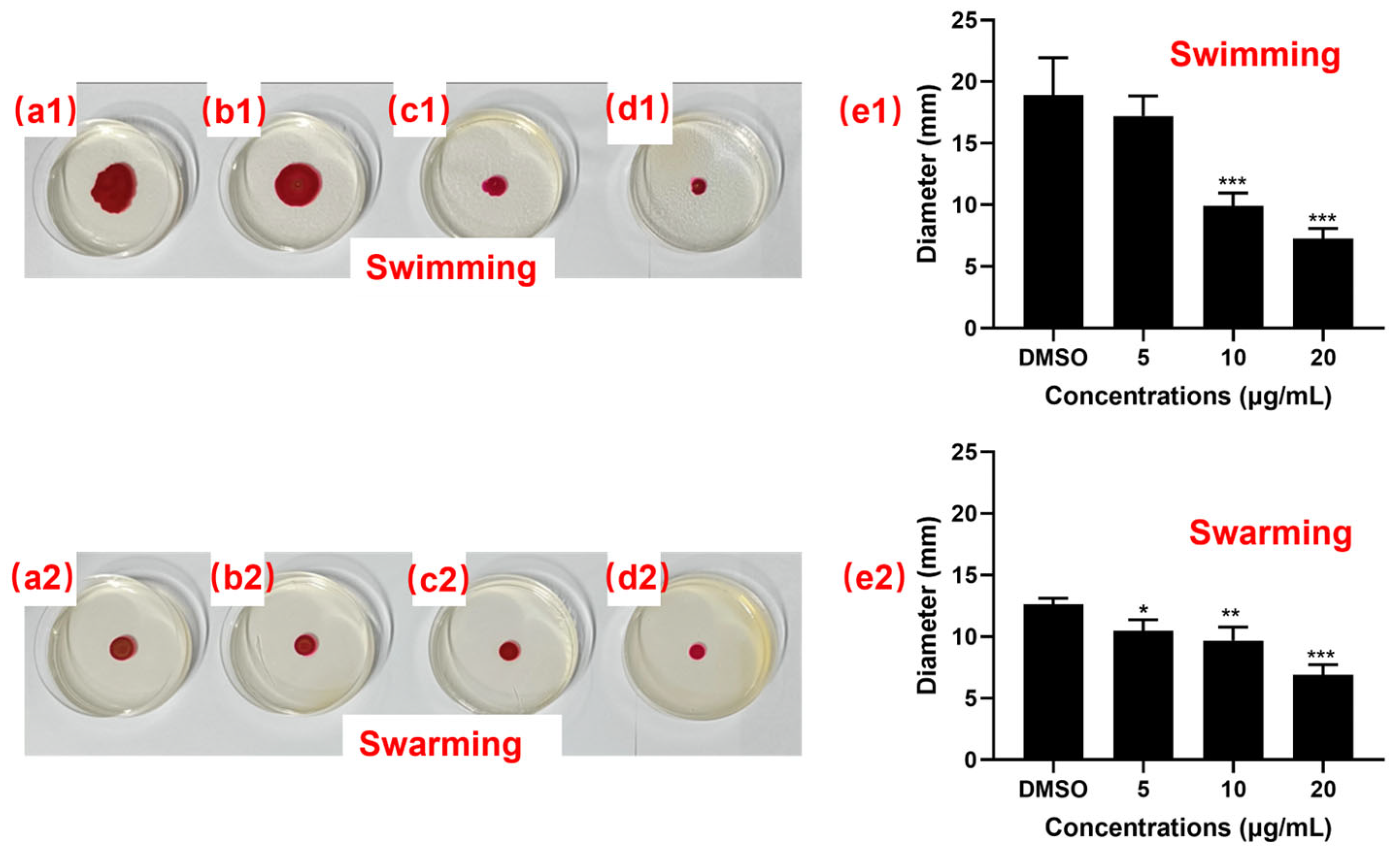

3.5.3. Motility Inhibition Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bates, S.S.; Hubbard, K.A.; Lundholm, N.; Montresor, M.; Leaw, C.P. Pseudo-nitzschia, Nitzschia, and domoic acid: New research since 2011. Harmful Algae 2018, 79, 3–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, M. Red algae. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, R841–R842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikov, A.N.; Flisyuk, E.V.; Obluchinskaya, E.D.; Pozharitskaya, O.N. Pharmacokinetics of marine-derived drugs. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piruthiviraj, P.; Swetha, B.M.; Balasubramanian, C.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Gatasheh, M.K.; Ahmad, A.; Parthasarathi, R.; Pandurangan, P.; Bhuvaneshwari, V.; Vijayakumar, N. Exploring the potential: Inhibiting quorum sensing through marine red seaweed extracts—A study on Amphiroa fragilissima. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klumpp, D.W.; Polunin, N.V.C. Partitioning among grazers of food resources within damselfish territories on a coral reef. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1989, 125, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Agusti, S.; Lin, F.; Li, K.; Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, J.; Duarte, C.M. Nutrient removal from Chinese coastal waters by large-scale seaweed aquaculture. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, I.G.; Miguel, M.G.; Mnif, W. A brief review on new naturally occurring cembranoid diterpene derivatives from the soft corals of the genera Sarcophyton, Sinularia, and Lobophytum since 2016. Molecules 2019, 24, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Liu, X.; Ling, C.; Cheng, J.; Guo, X.; He, H.; Ding, S.; Yang, Y. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship studies of conformationally restricted mutilin 14-carbamates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulcoop, D.G.; Shapland, P.D. Expedient synthesis of 17α,21-dihydroxy-9β,11β-epoxy-16α-methylpregna-1,4-diene-3,20-dione 21-acetate from prednisolone utilising a novel Mattox rearrangement. Steroids 2013, 78, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Guo, W.; Wu, W.; Jiang, H. Carbonylation access to phthalimides using self-sufficient directing group and nucleophile. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, I.; Matsushita, Y.; Asaka, N.; Ohmori, K.; Nomura, N.; Ogawa, K. Synthesis and aldose reductase inhibitory activity of acetic acid derivatives of pyrrolo[1,2-c]imidazole. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 28, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, P.G.; Southan, G.J.; Baloglu, E.; Ram, S.; Mabley, J.G.; Marton, A.; Salzman, A.; Szabó, C. The discovery and synthesis of novel adenosine substituted 2,3-dihydro-1H-isoindol-1-ones: Potent inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Cravillion, T.; Lim, N.-K.; Tian, Q.; Beaudry, D.; Defreese, J.L.; Fettes, A.; James, P.; Linder, D.; Malhotra, S.; et al. Development of an efficient manufacturing process for reversible Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor GDC-0853. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018, 22, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlin, N.; Courty, M.; Van Nhien, A.N.; Gatard, S.; Pour, M.; Quilty, B.; Ghavre, M.; Haiß, A.; Kümmerer, K.; Gathergood, N.; et al. Tetrabutylammonium prolinate-based ionic liquids: A combined asymmetric catalysis, antimicrobial toxicity and biodegradation assessment. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 26241–26251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShan, D.; Kathman, S.; Lowe, B.; Xu, Z.; Zhan, J.; Statsyuk, A.; Ogungbe, I.V. Identification of non-peptidic cysteine reactive fragments as inhibitors of cysteine protease rhodesain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 4509–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.R.; Parsons, A.F.; Pons, J.-F.; Wilson, M. Tandem radical cyclisations leading to indolizidinones and pyrrolizidinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 7197–7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wochele, A.; Luo, M.; Schnakenburg, G.; Sun, Y.; Brötz-Oesterhelt, H.; Dickschat, J.S. Synthesis of tryptophan-dehydrobutyrine diketopiperazine and biological activity of hangtaimycin and its co-metabolites. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2022, 18, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.L.; Liang, J.; Teat, S.J.; Garzón-Ruiz, A.; Nenon, D.P.; Navarro, A.; Liu, Y. A highly substituted pyrazinophane generated from a quinoidal system via a cascade reaction. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 4472–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettori, M.A.; Fabbri, D.; Dessì, A.; Dallocchio, R.; Carta, P.; Honisch, C.; Ruzza, P.; Farina, D.; Migheli, R.; Serra, P.A.; et al. Synthesis and studies of the inhibitory effect of hydroxylated phenylpropanoids and biphenols derivatives on tyrosinase and laccase enzymes. Molecules 2020, 25, 2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, T.S.; Brunson, J.K.; Maeno, Y.; Terada, R.; Allen, A.E.; Yotsu-Yamashita, M.; Chekan, J.R.; Moore, B.S. Domoic acid biosynthesis in the red alga Chondria armata suggests a complex evolutionary history for toxin production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2117407119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajski, G.; Gerić, M.; Baričević, A.; Smodlaka Tanković, M. Domoic acid: A review of its cytogenotoxicity within the one health approach. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Portalatino, E.J.; Rosales-Cuentas, M.M.; Tamariz-Angeles, C.; Olivera-Gonzales, P.; Espinoza-Espinoza, L.A.; Moreno-Quispe, L.A.; Portalatino-Zevallos, J.C. Diversity of endophytic bacteria with antimicrobial potential isolated from marine macroalgae from Yacila and Cangrejos beaches, Piura-Peru. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Kovács, Á.T. How to identify and quantify the members of the Bacillus genus? Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 26, e16593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Gu, H.; Bughio, A.A.; Liu, J. Optimization of fermentation conditions for 2,3,5-trimethylpyrazine produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens from Daqu. Fermentation 2024, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, F.; Tang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, M.; Fu, A.; Li, W. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 alleviated intestinal damage induced by inflammatory via modulating intestinal microbiota and intestinal stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 130, 111675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horyanto, D.; Bajagai, Y.S.; Kayal, A.; von Hellens, J.; Chen, X.; Van, T.T.H.; Radovanović, A.; Stanley, D. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens probiotics mix supplementation in a broiler leaky gut model. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Nie, L.; Xie, W.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, W.-W. Potentiation effect of the AI-2 signaling molecule on postharvest disease control of pear and loquat by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens and its mechanism. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.A.; Silva, L.A.; Brugnera, H.C.; Pereira, N.; Casagrande, M.F.; Makino, L.C.; Bragança, C.R.; Schocken-Iturrino, R.P.; Cardozo, M.V. Association of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens: Minimizes the adverse effects of necrotic enteritis in the gastrointestinal tract and improves zootechnical performance in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, L.; Sun, B.; Qu, M.; Zhu, X. Understanding the effect and mechanism of ε-polylysine on the improvement of tofu storage quality via biofilm inhibition by Bacillus licheniformis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Food Biosci. 2025, 66, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-S.; Shi, X.-H.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Shao, C.-L.; Fu, X.-M.; Li, X.; Yao, G.-S.; Wang, C.-Y. Benzyl Furanones and Pyrones from the Marine-Derived Fungus Aspergillus terreus Induced by Chemical Epigenetic Modification. Molecules 2020, 25, 3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, J.; Lyons, T.; Heras, V.L.; Recio, M.V.; Gahan, C.G.; O’SUllivan, T.P. Investigation of halogenated furanones as inhibitors of quorum sensing-regulated bioluminescence in Vibrio harveyi. Future Med. Chem. 2023, 15, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Lo, C.; Walsh, C.; Hiller, N.L.; Marculescu, R. In silico evaluation of the impacts of quorum sensing inhibition (QSI) on strain competition and development of QSI resistance. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, K.C.; Yusoff, F.M.; Natrah, F.M.; De Zoysa, M.; Yasin, I.S.M.; Yaminudin, J.; Karim, M. Biological strategies in aquaculture disease management: Towards a sustainable blue revolution. Aquac. Fish. 2025, 10, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alum, E.U.; Gulumbe, B.H.; Izah, S.C.; Uti, D.E.; Aja, P.M.; Igwenyi, I.O.; Offor, C.E. Natural product-based inhibitors of quorum sensing: A novel approach to combat antibiotic resistance. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 43, 102111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Dong, X.; Tan, Y.; Soteyome, T.; Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. Quorum sensing inhibition of hordenine on Bacillus cereus: Potential application of barley extract in food storage. LWT 2025, 227, 117952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

You, C.; Ding, Z.-W.; Jia, A.-Q.; Xu, K.-Z. Discovery and Activity Evaluation of Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors from an Endophytic Bacillus Strain W10-B1 Isolated from Coelothrix irregularis. Bacteria 2026, 5, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria5010003

You C, Ding Z-W, Jia A-Q, Xu K-Z. Discovery and Activity Evaluation of Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors from an Endophytic Bacillus Strain W10-B1 Isolated from Coelothrix irregularis. Bacteria. 2026; 5(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria5010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleYou, Chang, Zhi-Wen Ding, Ai-Qun Jia, and Kai-Zhong Xu. 2026. "Discovery and Activity Evaluation of Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors from an Endophytic Bacillus Strain W10-B1 Isolated from Coelothrix irregularis" Bacteria 5, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria5010003

APA StyleYou, C., Ding, Z.-W., Jia, A.-Q., & Xu, K.-Z. (2026). Discovery and Activity Evaluation of Quorum-Sensing Inhibitors from an Endophytic Bacillus Strain W10-B1 Isolated from Coelothrix irregularis. Bacteria, 5(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/bacteria5010003