Monetary Transmission & Small Firm Credit Rationing: The Stablecoin Opportunity to Raise Business Credit Flows

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Money and the Real Economy

3. Cryptocurrencies

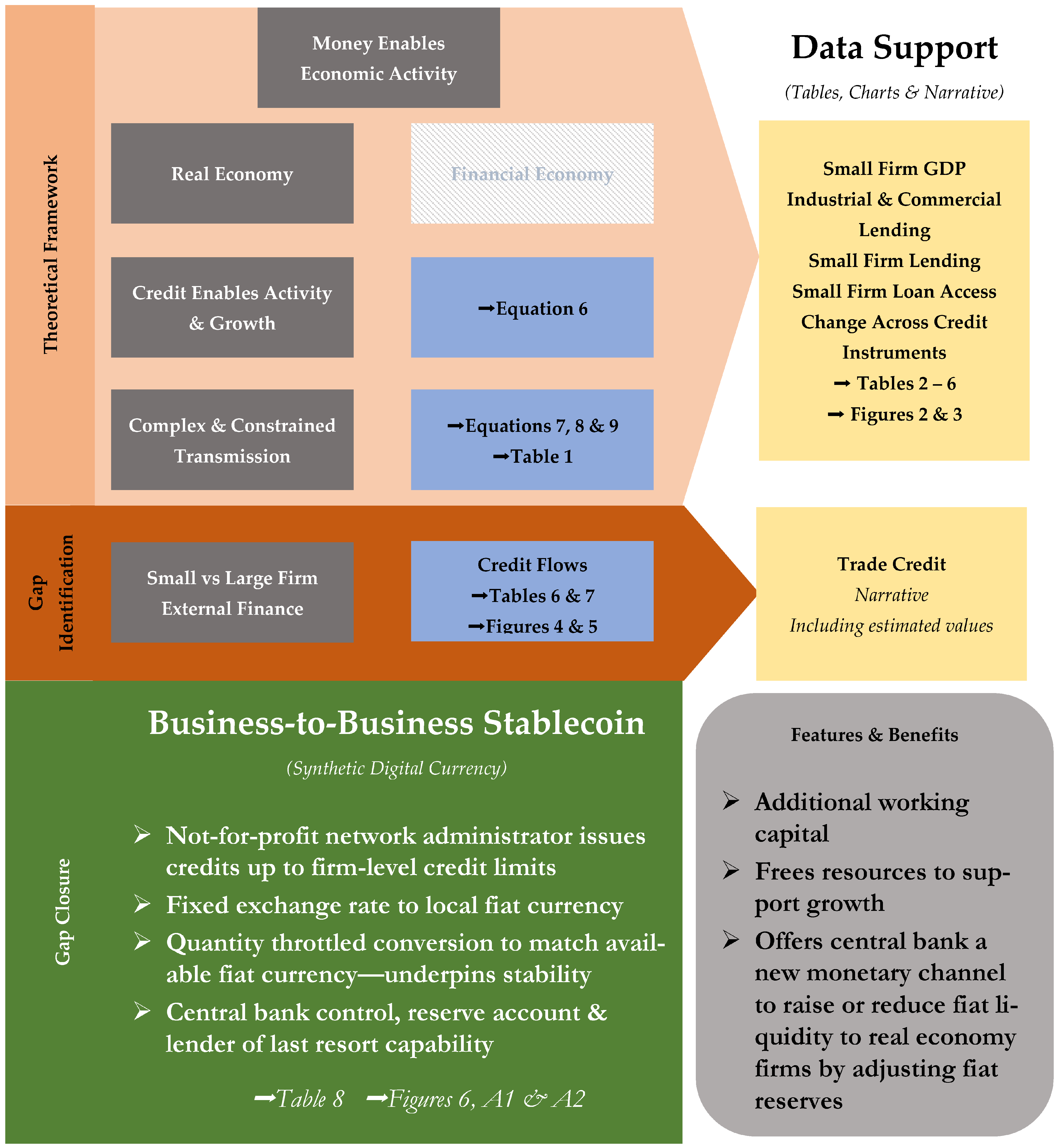

4. Financial vs. Real Economy

- What is the nature of the industrial and commercial credit rationing gap?

- Could a central bank-aligned stablecoin help reduce credit rationing?

5. Materials & Methodology

5.1. Analytical Framework

5.2. Theoretical Framework

5.3. Monetary/Credit Transmission

5.4. Transmission Dynamics

5.5. The Monetary Transmission Universe

5.6. Data Considerations

5.7. Data Setting (Results)

5.8. Small Firm Lending Landscape

6. Discussion

6.1. Trade Credit—A Vital Source of Non-Bank External Credit

6.2. Stablecoin-Enabled Trade Credit

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Annex Trade Credit Stablecoin Design Framework

References

- Chohan, U.W. A History of Bitcoin. SSRN Electron. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, G.; Carapella, F.; Gerszten, J.; Mills, D. The Stable in Stablecoins; Fed Notes; US Federal Reserve: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/the-stable-in-stablecoins-20221216.html#:%7E:text=Stablecoins%20facilitate%20trades%20on%20crypto,of%20value%20for%20these%20transactions (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Jean, B.; Gardin, P.; Nguyen, B. Stablecoins and the Financing of the Real Economy; Working Paper #908; Banque De France: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://abc-economie.banque-france.fr/sites/default/files/medias/documents/wp908_1.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- De, N. Tether’s Banking Relationships, Commercial Paper Exposure Detailed in Newly Released Legal Documents, Coindesk: NY, June 2023, Based on Freedom of Information Disclosure By New York Attorney General Office. 2023. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/policy/2023/06/16/tethers-banking-relationships-commercial-paper-exposure-detailed-in-newly-released-legal-documents/ (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- BDO Tether Holdings Limited. Independent Auditors Report on the Consolidated Financials Figures and Reserves Report Q1 2024; BDO: Milan, Italy, 2024; Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/vyse88cgwfbl/2JwUN6EeDvWi02CyuQd2nJ/d7b3b4c3800ec70abd7282cc79fa2973/ISAE_3000R_-_Opinion_on_Consolidated_Financials_Figures_and_Reserves_Report_31.03.2024_RC134792024BD0043.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- IFRS 9 Financial Instruments; IFRS: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ifrs-9-financial-instruments/ (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Wu, G.S.T.; Leung, P.H. Do asset-backed stablecoins spread crypto volatility to traditional financial assets? Evidence from Tether. Econ. Lett. 2023, 229, 111213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.M. Short-term market impact of crypto firms’ bankruptcies on cryptocurrency markets. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2024, 70, 102370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, C. Stablecoins: Adoption and Fragility; Working Paper #423; Sveriges Riksbank: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023; Available online: https://www.riksbank.se/globalassets/media/rapporter/working-papers/2023/no.-423-stablecoins-adoption-and-fragility.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- Hornuf, L.; Kück, T.; Schwienbacher, A. Initial Coin Offerings, Information Disclosure, and Fraud. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 1741–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Financial Stability Board. Financial Stability Risks of Decentralised Finance; Financial Stability Board: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.fsb.org/2023/02/the-financial-stability-risks-of-decentralised-finance/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Lummis, Gillibrand Introduce Bipartisan Landmark Legislation to Create Regulatory Framework for Stablecoins; Kirsten Gillibrand|U.S. Senator for New York; US Senate: Washinton, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.gillibrand.senate.gov/news/press/release/lummis-gillibrand-introduce-bipartisan-landmark-legislation-to-create-regulatory-framework-for-stablecoins/ (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Luck, S.; Zimmermann, T. Employment Effects of Unconventional Monetary Policy: Evidence from QE. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 135, 678–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karfakis, C.; Karfakis, I. Quantitative Easing and Systemic Risk in the Post-Lehman Era. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2023, 30, 1134–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, M.A.S.; Spaltro, M. Quantitative Easing and Bank Lending: A Panel Data Approach; Working Paper; Bank of England: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/working-paper/2014/quantitative-easing-and-bank-lending-a-panel-data-approach.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Calabrese, R.; Cowling, M.; Liu, W. Understanding the Dynamics of UK COVID-19 SME Financing. Br. J. Manag. 2022, 33, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Keil, J. Have Banks Caught Corona? Effects of COVID on Lending in the U.S. J. Corp. Finance 2022, 72, 102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small Business Paycheck Protection Program. United States Treasury. 2023. Available online: https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/PPP%20--%20Overview.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Filomeni, S. The Impact of the Paycheck Protection Program on the Risk-Taking Behaviour of US Banks. Rev. Quant. Finance Acc. 2024, 62, 1329–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.; Jang, Y.S.; Kaplan, S.; Schulze, A. A Survey of Private Debt Funds; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://academic.oup.com/rcfs/article-abstract/13/2/335/7609046?redirectedFrom=PDF&casa_token=FnKH0Tge8UYAAAAA:dGBv-qvpiZpNDpdgSbnTmfzWOI-GATGSGQF22evMkHgFCbznGUcow1Zgp5YKQGflO9iCAbzQcP7YVg (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Catalini, C.; de Gortari, A.; Shah, N. Some Simple Economics of Stablecoins. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2022, 14, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukierman, A. COVID-19, Seignorage, Quantitative Easing and the Fiscal-Monetary Nexus. Comp. Econ. Stud. 2021, 63, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vousinas, G.L. Supervision of Financial Institutions: The Transition from Basel I to Basel III. A Critical Appraisal of the Newly Established Regulatory Framework. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2015, 23, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penikas, H. Money Multiplier under Basel Capital Ratio Regulation: Implications for Counter-COVID-19 Stimulus. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2023, 13, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Weiss, A. Credit Rationing in Markets with Imperfect Information. Am. Econ. Rev. 1981, 71, 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W.; Wang, Q. The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Businesses in the US: A Longitudinal Study from a Regional Perspective. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2023, 46, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozzella, P.; Gabbi, G. What Is Good and Bad with the Regulation Supporting the SME’s Credit Access. J. Financ. Regul. Compliance 2020, 28, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savlovschi, L.I.; Robu, N.R. The role of SMEs in modern economy. Econ. Ser. Manag. 2011, 14, 277–281. Available online: https://management.ase.ro/reveconomia/2011-1/25.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Kaldor, N. The new monetarism. Lloyds Bank Rev. 1970, 97, 18. Available online: http://public.econ.duke.edu/~kdh9/Courses/Graduate%20Macro%20History/Readings-1/Kaldor.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Bank of England Money Creation in the Modern Economy. Bank of England: Quarterly Bulletin Q1 2014. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/quarterly-bulletin/2014/q1/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Simmons, R.; Dini, P.; Culkin, N.; Littera, G. Crisis and the Role of Money in the Real and Financial Economies—An Innovative Approach to Monetary Stimulus. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, I. “The Equation of Exchange”, 1896–1910. Am. Econ. Rev. 1911, 1, 296–305. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, J.M. A Treatise on Money; Cambridge University Press for The Royal Economic Society: Cambridge, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, H.P. Schumpeter: Finance and Evolution; Hyman P. Minsky Archive #314; Levy Economic Institute Bard College: Annandale on Hudson, NY, USA, 1988; Available online: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/hm_archive/314 (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Friedman, M. The Role of Monetary Policy. Am. Econ. Rev. 1968, 58, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Boivin, J.; Kiley, M.T.; Mishkin, F.S. How has the monetary transmission mechanism evolved over time? In Handbook of Monetary Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 3, pp. 369–422. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, H.P. The Financial-Instability Hypothesis: Capitalist Processes and the Behaviour of the Economy; Levy Economics Institute of Bard College: New York, NY, USA, 1982; Available online: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1281&context=hm_archive (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Keynes, J.M. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money; Macmillan & Co: London, UK, 1936; pp. xii+403. [Google Scholar]

- EU SAFE Survey on Access to Finance of Enterprises Analytical Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/document/download/498e0a83-f1db-4a1f-8cc7-b20fa9a7effd_en?filename=Analytical%20Report%20SAFE%202023.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Perez-Orive, A.; Timmer, Y.; van der Ghote, A. The Asymmetric Credit Channel of Monetary Policy. Unpublished Paper on AEAweb. 2023. Available online: https://papers.yannicktimmer.com/asymmetry.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Weiss, A. Asymmetric Information in Credit Markets and Its Implications for Macro-Economics. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 1992, 44, 694–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, O.; Moore, J. A Theory of Debt Based on the Inalienability of Human Capital. Q. J. Econ. 1994, 109, 841–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSB, The Federation of Small Businesses. Super-Complaint Calls out Banks’ Use of Harsh Personal Guarantees Which can Force Small Business Owners to Put Their Homes on the Line; FSB: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.fsb.org.uk/resources-page/super-complaint-calls-out-banks-use-of-harsh-personal-guarantees-which-can-force-small-business-owners-to-put-their-homes-on-the-line.html (accessed on 16 December 2023).

- Ben Naceur, S.; Marton, K.; Roulet, C. Basel III and Bank-Lending: Evidence from the United States and Europe. J. Financ. Stab. 2018, 39, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E.; O’Toole, C.M. Bank Lending Constraints, Trade Credit and Alternative Financing during the Financial Crisis: Evidence from European SMEs. J. Corp. Financ. 2014, 27, 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bandt, O.; Durdu, B.; Ichiue, H.; Mimir, Y.; Mohimont, J.; Nikolov, K.; Roehrs, S.; Sahuc, J.G.; Scalone, V.; Straughani, M. Assessing the Impact of Basel III: Review of Transmission Channels and Insights from Policy Models; Forthcoming Article; International Journal of Central Banking; US Federal Reserve: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.ijcb.org/journal/ijcb24q1a1.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Durdu, C.B.; Zhong, M. Understanding Bank and Nonbank Credit Cycles: A Structural Exploration. J. Money Credit Bank. 2023, 55, 103–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicksell, K. Interest and Prices 1898 tr Khan 1936; Royal Economic Society by Macmillan: London, UK, 1898; pp. xxxi+238. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, B.; Ivashina, V. Cyclicality of Credit Supply: Firm Level Evidence. J. Monet. Econ. 2014, 62, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, J. Money and Economic Growth. Econometrica 1965, 33, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, F. Risk Uncertainty and Profit; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, A.W. Reconciling the Efficient Markets with Behavioural Finance: The Adaptive Markets Hypothesis; Portland State University: Portland, OR, USA, 2005; Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=d6d514fddae3287d1fc8ca55f601b1fa8d4be3d8 (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Hahn, F.H. A Note on Profit and Uncertainty. Economica 1947, 14, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US FED Schedule Z.1 Flow of Funds, Balance Sheets, and Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts; US Federal Reserve: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/20230608/z1.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- US FED Federal Reserve Board: Data Download Program—Home; Federal Reserve: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/DataDownload/default.htm (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- US FED Financial Accounts Guide—Series Analyzer; US Federal Reserve: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/fof/SeriesAnalyzer.aspx?s=FL103169005&t= (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- KANSAS FED Small Business Lending Survey. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City: Kansas City, MO, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.kansascityfed.org/surveys/small-business-lending-survey/ (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- BEA U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Gross Domestic Product (Implicit Price Deflator) 191RD3A086NBEA], 2024. Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 2024. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A191RD3A086NBEA (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- BEA U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Real Gross Domestic Product [GDPC1], Retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 2024. Available online: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GDPC1 (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- US FED. Assets and Liabilities Of Commercial Banks in the United States—H.8—April 26, 2024; Federal Reserve Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h8/current/ (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- US FED. E.2 Release—Survey of Terms of Business Lending—Current Release; Federal Reserve Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/e2/Current/default.htm (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- SBA. Small-Business-GDP-1998-2014; US Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Small-Business-GDP-1998-2014.pdf (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- US FED. Availability of Credit to Small Businesses, US Federal Reserve Washington DC, Report to Congress; Federal Reserve Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/sbfreport2017.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- US FED. Availability of Credit to Small Businesses, US Federal Reserve Washington DC, Report to Congress; Federal Reserve Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/sbfreport2022.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- US FED. Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2024. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/data/sloos.htm (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Kraemer-Eis, H.; Botsari, A.; Gvetadze, S.; Lang, F.; Torfs, W. The European Small Business Finance Outlook 2023. No. 2023/96. EIF Working Paper. 2023. Available online: https://www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/eif_working_paper_2023_96.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2024).

- EU SAFE. Survey on Access to Finance of Enterprises Analytical Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/32781/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- EU Commission. Access to Finance Worries Small and Medium Enterprises; European Commission, Enterprise and Industry Directorate: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/7925/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- EBA. EBA Report on SME’s and SME Supporting Factor; EBA/OP/2016/04; European Bank Authority: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.eba.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/10180/1359456/602d5c61-b501-4df9-8c89-71e32ab1bf84/EBA-Op-2016-04%20%20Report%20on%20SMEs%20and%20SME%20supporting%20factor.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Statista. Statista Bank Loans in the European Union; Statista: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cosh, A.; Hughes, A.; Bullock, A.; Milner, I. Financing UK Small and Medium Sized Enterprises; Centre for Business Research, Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 2007; Available online: https://www.jbs.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/cbr-sme-finance-report-final.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- BVA BDRC. “SME Finance Monitor, Market Research” Commissioned by UK Finance; BVA BDRC: London, UK, 2022; Available online: https://bva-bdrc.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/BVABDRC_SME_FM_Q4_2022_Chart_pack-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- IAS. IAS 7 Statement of Cash Flows; IFRS: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ias-7-statement-of-cash-flows/ (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- BIS. Basel III: International Regulatory Framework for Banks; Basel Committee on Bank Supervisions, BIS: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/basel3.htm?m=76 (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- FDIC Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Quarterly Banking Profile; Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.fdic.gov/analysis/quarterly-banking-profile/ (accessed on 28 April 2024).

- Gopal, M.; Schnabl, P. The Rise of Finance Companies and FinTech Lenders in Small Business Lending. Rev. Finance Stud. 2022, 35, 4859–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMF. Financial Access Survey Data Download Outstanding SME Loans from Commercial Banks; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://data.imf.org/?sk=e5dcab7e-a5ca-4892-a6ea-598b5463a34c&sid=1390030341854 (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Klepper, S.; Graddy, E. The evolution of new industries and the determinants of market structure. RAND J. Econ. 1990, 21, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Commission. Are EU SMEs Recovering from the Crisis? Annual Report on EU Small and Medium Sized Enterprises 2010/2011, EU Commission: Rotterdam. 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/15770/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Chen, S.; Lee, D. Small and Vulnerable: SME Productivity in the Great Productivity Slowdown. J. Financ. Econ. 2023, 147, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Fu, J. Credit Rationing, Innovation, and Productivity: Evidence from Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises in China. Econ. Model. 2021, 97, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iResearch. Report on the Financing Development of Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises in China; iResearch: Shanghai, China, 2021; Available online: https://pdf.dfcfw.com/pdf/H3_AP202111161529349179_1.pdf?1637060786000.pdf (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Hutton, G. Business Statistics, House of Commons Library Research Briefing. 2022. Available online: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn06152/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- IMF. Real GDP Percentage Change Download; World Economic Outlook; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Fed System. Joint Small Business Credit Survey Report, 2014; Fed Reserve Banks of New York, Atlanta, Cleaveland & Philadelphia: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.fedsmallbusiness.org/-/media/project/smallbizcredittenant/fedsmallbusinesssite/fedsmallbusiness/files/2015/sbcs-2014-report.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Block, J.; Jang, Y.S.; Kaplan, S.N.; Schulze, A. A survey of private debt funds. Rev. Corp. Financ. Stud. 2024, 13, 335–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEA. “Value Added by Industry as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product”, Interactive Access to Industry Economic Accounts Data; US Bureau of Economic Affairs: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/?reqid=150&step=2&isuri=1&categories=gdpxind#eyJhcHBpZCI6MTUwLCJzdGVwcyI6WzEsMiwzXSwiZGF0YSI6W1siY2F0ZWdvcmllcyIsIkdkcHhJbmQiXSxbIlRhYmxlX0xpc3QiLCI1Il1dfQ== (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Wilson, N.; Summers, B. Trade Credit Terms Offered by Small Firms: Survey Evidence and Empirical Analysis. J. Bus. Finance Account. 2002, 29, 317–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentz, H.; Solakivi, T.; Töyli, J.; Ojala, L. Trade Credit Dynamics during the Phases of the Business Cycle—A Value Chain Perspective. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2016, 21, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzet, N.; Mehrotra, N.R. Small and Large Firms over the Business Cycle. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 3549–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerra, V.; Fatás, A.; Saxena, S.C. Hysteresis and Business Cycles. J. Econ. Lit. 2023, 61, 181–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, V. Trade credit, payment duration, and SMEs’ growth in the European Union. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2023, 19, 1313–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, G.; Hogan, T. Bank credit and trade credit: Evidence from SMEs over the financial crisis. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 34, 412–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUF. EUF Estimates on EU Market; European Federation of Factoring & Commercial Finance: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Available online: https://euf.eu.com/data-statistics/euf-estimates.html (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- ECB. The Use of Trade Credit by Euro Area Non-Financial Corporations; Monthly Bulletin; European Central Bank: Frankfurt, Germany, 2011; pp. 24–28. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/mb201104_focus02.en.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Richter, H. Austrian Places: The Woergl Experiment. New Austrian. 2012. Available online: https://www.austrianinformation.org/summer-2012/2012/8/21/austrian-places-the-woergl-experiment.html (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Posnett, E. The Sardex Factor; Financial Times: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/cf875d9a-5be6-11e5-a28b-50226830d644 (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Cecioni, M.; Ferrero, B.N. 136—Determinanti Degli Squilibri Su TARGET2. Bancaditalia.it., Occasional Paper B. N. 136. Available online: https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/qef/2012-0136/index.html (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Bank of England. The Supplementary Special Deposits Scheme. Bank of England Quarterly Bulleting Q1 1982. Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/quarterly-bulletin/1982/q1/the-supplementary-special-deposits-scheme (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Adrian, T.; Mancini-Griffoli, T. The rise of digital money. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2021, 13, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Monetary Transmission Space | Credit Channel | Credit Product |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Banking |

|

|

| Shadow Banking |

|

|

| Crypto Assets |

|

|

| Central Bank/State |

|

|

| Commercial |

|

|

| Year | USA | China | UK |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 24.33 | 31.84 | 11.36 |

| 2012 | 24.47 | 35.09 | 10.29 |

| 2013 | 24.29 | 35.12 | 9.33 |

| 2014 | 24.58 | 36.29 | 8.97 |

| 2015 | 25.59 | 36.62 | 8.55 |

| 2016 | 26.31 | 36.00 | 8.29 |

| 2017 | 27.58 | 36.00 | 7.93 |

| 2018 | 29.59 | 35.56 | 7.69 |

| 2019 | 31.05 | 37.10 | 7.49 |

| 2020 | 33.68 | 41.67 | 10.11 |

| 2021 | 28.09 | 41.75 | 9.21 |

| Av % Real GDP Growth 2011–2021 | |||

| 2.3% | 7.0% | 1.4% | |

| Geography | 2007 | 2018 | 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejected Amount | Partial Amount | Full Amount | Rejected Amount | Partial Amount | Full Amount | Rejected Amount | Partial Amount | Full Amount | |

| UK | 15% | 19% | 66% | 26% | 10% | 65% | 48% | 6% | 46% |

| USA | 44% * | 21% * | 35% * | 26.5% † | NA | 73.5 † | 12% | 28.2 | 59.9% |

| EU | 15% ‡ | 15% ‡ | 70% ‡ | 6% | 10% | 74% | 4% | 20% | 61% |

| 2017 Constant Price | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USD Billions | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Total debt | 6933 | 7153 | 7431 | 7745 | 8208 | 8519 | 8907 | 9383 | 9706 | 10,421 | 10,324 |

| Industrial revenue and corporate bonds | 4403 | 4674 | 4891 | 5102 | 5486 | 5706 | 5352 | 5396 | 5563 | 6108 | 5895 |

| Mortgages | 623 | 477 | 452 | 408 | 446 | 479 | 532 | 608 | 650 | 681 | 761 |

| Bank loans not secured on real estate | 684 | 758 | 824 | 884 | 959 | 996 | 893 | 974 | 989 | 1046 | 946 |

| Commercial paper | 126 | 138 | 152 | 188 | 181 | 185 | 205 | 190 | 187 | 124 | 122 |

| Municipal securities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 570 | 554 | 561 | 555 | 532 |

| Other loans (shadow banks) | 1096 | 1105 | 1114 | 1163 | 2099 | 1153 | 1354 | 1660 | 1758 | 1906 | 2068 |

| MEMO trade credit | 1926 | 1957 | 2031 | 2157 | 2099 | 2170 | 2352 | 2611 | 2793 | 2875 | 3189 |

| Percentages of GDP | |||||||||||

| 2017 Constant Price | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Mortgages | 3.6% | 2.7% | 2.5% | 2.2% | 2.3% | 2.5% | 2.7% | 3.0% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 3.5% |

| Bank loans not secured on real estate | 3.9% | 4.3% | 4.6% | 4.7% | 5.0% | 5.1% | 4.5% | 4.8% | 4.8% | 5.0% | 4.3% |

| Industrial revenue and corporate bonds | 25.4% | 26.5% | 27.2% | 27.3% | 28.9% | 29.4% | 26.7% | 26.4% | 26.9% | 29.1% | 27.1% |

| Commercial paper | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% | 0.9% | 0.9% | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| Municipal securities | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 2.8% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.6% | 2.4% |

| Other loans (shadow banks) | 6.3% | 6.3% | 6.2% | 6.2% | 11.0% | 5.9% | 6.8% | 8.1% | 8.5% | 9.1% | 9.5% |

| Trade credit | 11.1% | 11.1% | 11.3% | 11.6% | 11.0% | 11.2% | 11.7% | 12.8% | 13.5% | 13.7% | 14.7% |

| 2017 Constant Price | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billions USD | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Total debt | 4226 | 4321 | 4361 | 4589 | 4862 | 5104 | 5528 | 5692 | 5870 | 6260 | 6106 |

| Mortgages | 3059 | 3098 | 3128 | 3274 | 3451 | 3635 | 3915 | 4029 | 4208 | 4372 | 4352 |

| Bank loans (not real estate secured) | 980 | 1031 | 1037 | 1112 | 1204 | 1261 | 1376 | 1422 | 1417 | 1557 | 1390 |

| Shadow bank loans (not real estate secured) | 186 | 193 | 196 | 202 | 207 | 207 | 237 | 241 | 245 | 331 | 363 |

| MEMO trade credit | 525 | 526 | 553 | 555 | 603 | 653 | 588 | 581 | 614 | 579 | 598 |

| Percent SME 2017 Constant Price GDP | |||||||||||

| Mortgages | 40% | 40% | 40% | 40% | 42% | 43% | 45% | 45% | 47% | 48% | 46% |

| Bank loans (not real estate secured) | 13% | 13% | 13% | 14% | 15% | 15% | 16% | 16% | 16% | 17% | 15% |

| Credit union supplied | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.8% | 1.9% |

| Finance company supplied | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.2% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.8% | 1.9% |

| Trade credit | 7.0% | 6.8% | 7.1% | 6.8% | 7.3% | 7.7% | 6.7% | 6.5% | 6.8% | 6.3% | 6.3% |

| Total | 55.9% | 56.2% | 55.8% | 56.5% | 58.8% | 60.5% | 63.4% | 64.1% | 65.3% | 68.6% | 64.6% |

| US Data 2017 Constant Price GDP | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortgages as % GDP | |||||||||||

| Small firms | 40.5% | 40.3% | 40.1% | 40.3% | 41.8% | 43.1% | 44.9% | 45.4% | 46.8% | 47.9% | 46.0% |

| All industrial and commercial firms | 3.6% | 2.7% | 2.5% | 2.2% | 2.3% | 2.5% | 2.7% | 3.0% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 3.5% |

| Non-Real Estate Loans % GDP | |||||||||||

| Small firms | 13.0% | 13.4% | 13.3% | 13.7% | 14.6% | 14.9% | 15.8% | 16.0% | 15.8% | 17.1% | 14.7% |

| All industrial and commercial firms | 3.9% | 4.3% | 4.6% | 4.7% | 5.0% | 5.1% | 4.5% | 4.8% | 4.8% | 5.0% | 4.3% |

| Bonds as % GDP | |||||||||||

| Small firms | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| All industrial and commercial firms | 25.4% | 26.5% | 27.2% | 27.3% | 28.9% | 29.4% | 26.7% | 26.4% | 26.9% | 29.1% | 27.1% |

| Trade Credit (Memo Estimate) | |||||||||||

| Small firms | 7.0% | 6.8% | 7.1% | 6.8% | 7.3% | 7.7% | 6.7% | 6.5% | 6.8% | 6.3% | 6.3% |

| All industrial and commercial firms | 11.1% | 11.1% | 11.3% | 11.6% | 11.0% | 11.2% | 11.7% | 12.8% | 13.5% | 13.7% | 14.7% |

| Trade Credit | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small firms % GDP | 7.0% | 6.8% | 7.1% | 6.8% | 7.3% | 7.7% | 6.7% | 6.5% | 6.8% | 6.3% | 6.3% |

| Large firms % GDP | 11.1% | 11.1% | 11.3% | 11.6% | 11.0% | 11.2% | 11.7% | 12.8% | 13.5% | 13.7% | 14.7% |

| Difference | 4.1% | 4.2% | 4.2% | 4.7% | 3.8% | 3.4% | 5.0% | 6.2% | 6.7% | 7.4% | 8.3% |

| Small firm current price GDP | 6728 | 7008 | 7259 | 7581 | 7901 | 8109 | 8428 | 8890 | 9255 | 9262 | 9977 |

| Unconstrained small firm trade credit (calc. from small firm GDP) | 746 | 776 | 821 | 876 | 873 | 907 | 989 | 1137 | 1251 | 1268 | 1464 |

| Actual small firm trade credit | 483 | 494 | 528 | 537 | 588 | 646 | 593 | 599 | 642 | 615 | 675 |

| Gap (est. additional funding requirement) | 263 | 282 | 293 | 339 | 285 | 261 | 396 | 538 | 609 | 653 | 789 |

| USD Billion Euro Converted at 1 EUR = USD 1.08 | US | EU | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing | Un-Constrained | 30% | 50% | 75% | Existing | Un-Constrained | 30% | 50% | 75% | |

| All firms | 18,540 | 6.4% | 10.7% | 16.1% | 4300 | 10% | 17% | 25% | 18,540 | 6.4% |

| Small firms | 6890 | 9.8% | 16.3% | 24.5% | 2471 | 6% | 9% | 14% | 6890 | 9.8% |

| Euro converted at 1 EUR = USD 1.08 | USA | EU | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total External Financing US | Firm Take-Up of New Instrument | Total External Financing EU | Firm Take-Up of New Instrument | |||||

| 30% | 50% | 75% | 30% | 50% | 75% | |||

| All firms | 18,540 | 6.4% | 10.7% | 16.1% | 4300 | 10% | 17% | 25% |

| Small firms | 6890 | 9.8% | 16.3% | 24.5% | 2471 | 6% | 9% | 14% |

| Event | Network Admin Transaction | Fiat Reserve | Currency Control | Charges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External firms purchase goods from network firm | External firm remits cash to purchase stablecoin to settle invoice | + | None | None |

| Network firm purchases goods from external firm | Network firm remits stablecoin that is exchanged for cash remitted to pay invoice | − | Yes | Yes |

| Network firm purchases goods from network firm | Balance is transferred from one member to another | None | Yes | |

| Central bank boosts real economy money supply to firms | Central bank injects conversion liquidity in return for security over network manager loans to firms | + | None | None |

| Central bank withdraws cash | Central bank reduces conversion liquidity, reducing security over network manager loans | − | None | None |

| Network administrator builds reserve account | % Firm fee income hypothecated to reserve account | + | None | None |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simmons, R. Monetary Transmission & Small Firm Credit Rationing: The Stablecoin Opportunity to Raise Business Credit Flows. FinTech 2024, 3, 379-406. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech3030021

Simmons R. Monetary Transmission & Small Firm Credit Rationing: The Stablecoin Opportunity to Raise Business Credit Flows. FinTech. 2024; 3(3):379-406. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech3030021

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimmons, Richard. 2024. "Monetary Transmission & Small Firm Credit Rationing: The Stablecoin Opportunity to Raise Business Credit Flows" FinTech 3, no. 3: 379-406. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech3030021

APA StyleSimmons, R. (2024). Monetary Transmission & Small Firm Credit Rationing: The Stablecoin Opportunity to Raise Business Credit Flows. FinTech, 3(3), 379-406. https://doi.org/10.3390/fintech3030021