1. Introduction

Time banks (TBs) represent a dynamic concept in the realm of financial systems, shaped by diverse socio-economic phenomena and challenges that continually redefine their scope and significance. Unlike conventional financial systems, TBs are characterized by fundamental principles of equity, equality, and reciprocity among their members, reflecting a multidisciplinary approach to addressing societal needs. Exploration of the scientific literature underscores the complementary nature of TBs alongside traditional financial systems, emerging as responsive mechanisms to societal demands and challenges impacting financial structures. This study aims to elucidate various global models of TBs, offering detailed insights into their defining characteristics and their profound significance in meeting societal needs. Viewed as supportive and complementary financial instruments, TBs embody values such as accessibility, tolerance, and transparency, making them adaptable to local contexts. Moreover, this research endeavors to define the financial instrument of “Time Bank”, contributing to the ongoing innovation dynamics within the financial system, particularly geared towards fulfilling the diverse needs of local communities. Leveraging technology as metasystems based on knowledge and Systems Theory, time banks are poised to enhance financial processes, facilitating efficient management through online platforms for logging hours worked and accessing services, thereby fostering collaboration and knowledge sharing within communities. Despite the inherent challenges such as valuing services and ensuring fair participation, time banks represent a creative approach to economic exchange and community building. As innovative financial instruments, they allow for the exchange of value outside traditional monetary systems. To elucidate their potential, this paper proposes identifying and exploring several scientific considerations within the specialized literature regarding time banks and their impact and potential, as well as participation in time banks, offering individuals the opportunity to meet needs without monetary dependency or debt, thus adding a social dimension to the economic landscape. Time banks have a rich conceptual history, originating in the United States and expanding globally. While their exact count remains elusive due to their adaptable nature, TBs are considered complementary currencies, operating parallel to mainstream monetary economies. They facilitate exchanges based on time units, offering a platform for individuals to exchange skills and services.

The concept of TBs is multidisciplinary, with educational and social responsibility aspects intertwined. The incentivization of community engagement and problem solving within TBs reflects principles articulated by renowned economists such as Mill J.S. and underpins the coproduction principle outlined by Edgar S. Cahn.

TBs are characterized by their adaptability to various cultural environments and regional realities, reflecting their chameleonic nature. Despite challenges in identification and quantification, TBs play a crucial role in fostering community collaboration and social capital development.

The bookkeeping aspect of TBs extends beyond recording exchanges to include contributions to community building and problem solving, simplifying monitoring and evaluation processes. This multidimensional approach underscores the complex yet impactful nature of TBs in reshaping economic and social paradigms.

As we delve deeper into this study, we find that the accounting aspect of time banks (TBs) goes beyond simply keeping transactional records. It includes vital contributions to community growth and problem solving, streamlining monitoring and evaluation procedures. Through our personal contribution to this research, we aim to enrich the scientific literature by shedding light on the multifaceted and interdisciplinary nature of TBs. By highlighting the complex yet powerful impact of TBs on economic and social paradigms, we hope to provide valuable insights derived from the bibliometric analysis identified and presented in this study.

Literature Review

Time banks have a rich conceptual history, characterized by their ability to leverage individuals’ skills and professional qualities, which operate outside the regulatory frameworks of the traditional job market. Originating in the United States, this concept has expanded globally, with some sources [

1] suggesting the world’s first time banks (TBs) began in Japan in the 1970s, initiated by Teruko Mizushima. Nevertheless, their global recognition only ensued nearly a decade later, coinciding with the introduction of a Time Dollar in the United States [

2]. TBs, at their core, use time units as currency [

3]. Functioning as a service-oriented initiative, time banks establish foundational principles applicable to various economic activities, facilitating interaction with other endeavors in related sectors [

4].

The prevalence of the social or trade aspect in a TB system is determined by its adaptation to the current needs of a community in a particular environment. TBs face challenges and adapt to various cultural environments, often reflecting regional realities to tackle local and regional issues [

5,

6].

The global count of TBs is in constant flux, making it challenging to determine their exact number [

7,

8]. TBs are considered “chameleonic” and challenging to identify, not only in terms of their quantity but also the number of participants [

9,

10]. Considered a complementary economic system, TBs are described as existing parallel to a mainstream monetary economy and are identified as complementary currency due to their use of time. Participants typically join for non-financial reasons [

10]. One study [

11] defines the time bank as a complex system that measures the effort expended by people to carry out their activities, in which effort is repaid through informal support when they need support, with time thus being a kind of “money” reward. At the same time, another author [

12] defines the time bank concept as a “community model”, and, based on it, exchanges are generated at the community level, as happened in the USA in the 1980s and in Great Britain during the end of the 1990s.

Returning to the idea of currency as an information system [

13], TB bookkeeping goes beyond recording exchanges, detailing contributions to community building, social capital, and problem solving [

14]. This feature adds value by simplifying the monitoring and evaluation of all exchanges [

15]. Identification of a TB previously relied on core values and adherence to the coproduction principle outlined by Edgar S. Cahn in the 1980s [

16]. Co-production involves individuals taking responsibility for solving problems, a principle found in various fields, including knowledge management and open-source software development [

17,

18]. In the context of time banks (TBs), a crucial aspect lies in the incentive provided to community members for engagement and participation, a concept articulated by the renowned economist Mill J.S. in his works [

19]. Its implication in global institutions, such as The International Labor Organization (ILO) (2022), presents mechanisms and support solutions for the development of small businesses, including the diversification of financing tools and risk reduction, where such a mechanism could be a time bank. The association between business performance, the use of bank loans [

20] and the orientation of the business environment towards new innovative financing instruments based on technology represents a new challenge in the reconfiguration of financial instruments. Moreover, this orientation of financial innovations towards technology (fintech) improves offerings for small entrepreneurs [

21]. However, it also poses challenges from the regulatory perspective for authorities and regulators, aspects that are also pertinent for time banks. Along with the scientific literature related to time banks, it is important to emphasize the multidisciplinary character of this concept, in which education has an essential role, both upstream and downstream [

22]. Global social responsibility means a reorientation of business activities [

23], inclusive at the level of specific time bank activities.

In the scientific literature, there are numerous valuable works [

24], which highlight that in recent years we have witnessed simultaneous processes of monetary innovation—the digitalization of money and the proliferation of social currencies. These trends have combined to give rise to digital social currencies [

24], which are appreciated as potentially relevant to the time bank model. Furthermore, ref. [

24] evaluates both the advantages and disadvantages of the complete digitalization of social currencies. Although new technologies and digitalization offer significant benefits, such as increased reach and efficiency of social currencies [

25], they are accompanied by important challenges, including the exclusion of users with limited digital skills. The study [

24] utilized multilevel logistic models and data from the Global Findex survey to identify segments of the population less likely to use digital payment methods, aiming to improve financial and digital inclusion globally.

A relevant example of a time bank is the Barakaldo Time Bank [

26], as an alternative for organizing and functioning within the community, while the time bank model [

27] is that of an online time bank. In [

28], the author explores the concept of the “time bank” as a strategy for mutual aid within communities. Additionally, ref. [

28] analyzes how time banks facilitate the exchange of services and resources among members without involving traditional financial transactions and indicates how these initiatives contribute to strengthening community ties and mutual support, highlighting the advantages and challenges faced in implementing and operating these systems and promoting a solidarity-based economy and stronger social cohesion [

29].

2. Materials and Methods

In the framework of the research methodology, classic tools specific to empirical studies were used, based primarily on the scientific literature on time banks (TBs). Furthermore, in our study, structuring working hypotheses helps us to use appropriate research tools such as bibliometric analyzes that allow us to quickly identify time bank patterns that respond to our structured hypotheses. Moreover, a primary methodological tool for understanding soft systems was defined by Checkland P., known as a “Soft System” [

30]. To understand why, from a methodological point of view, a system is considered soft rather than hard, the distinguishing characteristics of each type of system have been highlighted. It is observed that hard systems are easier to instrument, and authors such as Skyttner [

31] argue that these hard systems are easier to manage compared to soft systems and are characterized by a more general definition from a human perspective, proving more difficult to analyze and interpret, according to Checkland [

32]. These distinctive elements suggest the current situation where certain economies are defined as “soft power” economies.

In our research methodology, we adopted classic tools commonly used in empirical studies, primarily drawing from the scientific literature on time banks (TBs). Structuring working hypotheses guided our selection of appropriate research tools, such as bibliometric analysis, to swiftly identify patterns within time banks that align with our structured hypotheses.

A key methodological tool we employed to understand soft systems was Checkland P.’s “Soft System” methodology. This approach helped us grasp why certain systems are categorized as soft rather than hard, highlighting the distinguishing characteristics of each. Unlike hard systems, which are perceived as easier to instrument and manage, soft systems pose greater challenges due to their broader definition and the complexity introduced by human factors.

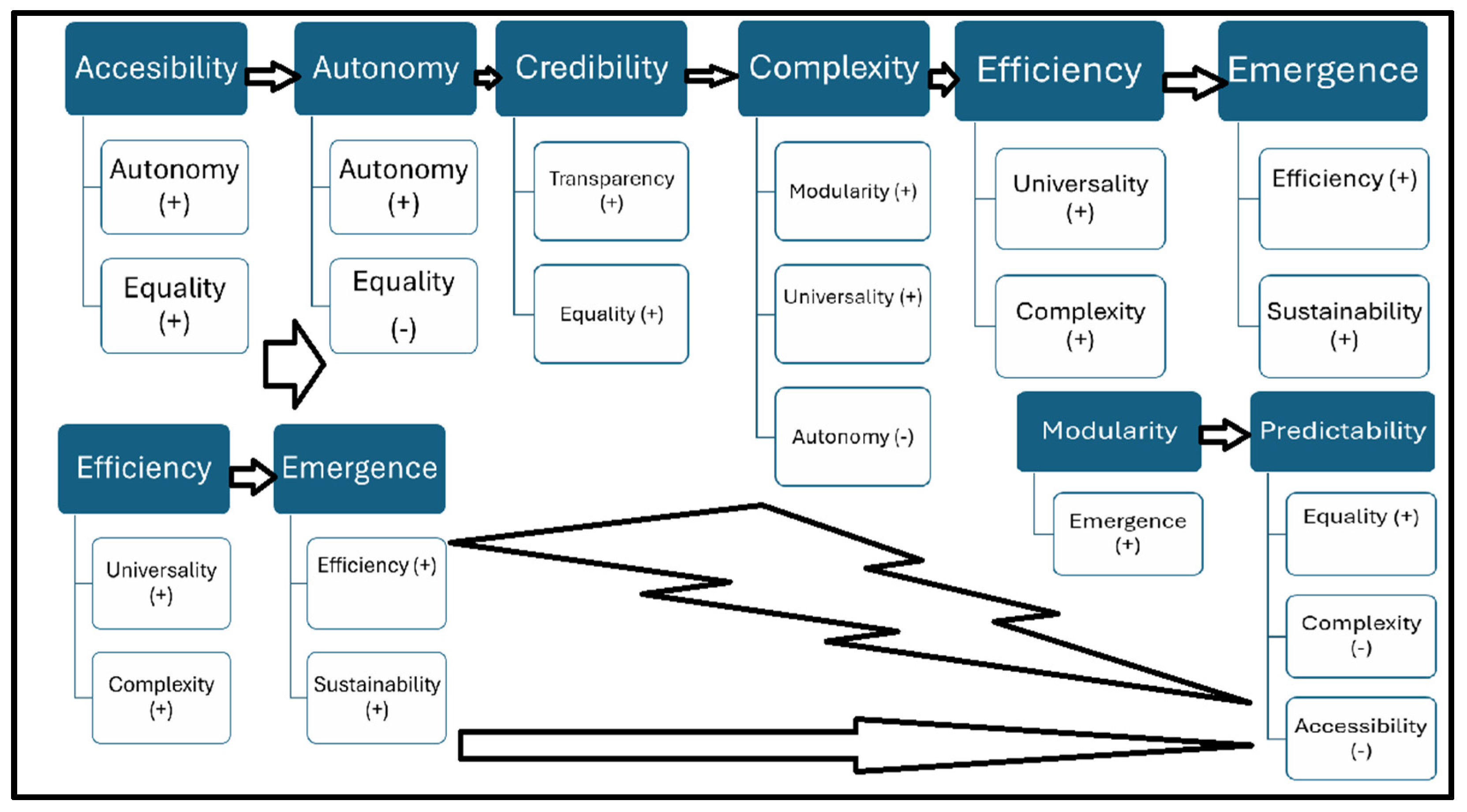

For the methodological analysis of time banks, we examined the variables defining the causal relationships between various factors and TBs, as identified in the specialized scientific literature. Among the most prevalent methodological tools encountered in our study were Causal Loop Diagrams (CLDs), popularized by Sterman [

33]. CLDs proved effective in capturing the polarity of reactions within time banks, shaping community behavior within the integrated system.

The Soft System Methodology (SSM) emerged as the most suitable approach for ana-lysing TBs, given their classification as “soft systems” by Checkland. Details on diagram notation, essential for understanding CLDs, were gleaned from works such as Sterman’s. Moreover, CLDs could be further developed into quantitative modeling tools, facilitating the transformation of qualitative models into quantitative ones.

By applying intuitive elements derived from our working hypotheses and adhering to established methodologies, we discerned that the innovative characteristics of a time bank are contingent upon the community’s abilities and characteristics. This nuanced perspective, reflected in our study’s results, serves as a response to our working hypotheses and underscores the unique soft qualities inherent in time banks.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis/Result Interpretation

The key outcome of the time bank (TB) analysis is a set of systemic features believed to be inherent to any TB to some extent. In the reference study [

17] of our work, characteristics of time banks are highlighted that work together as an element of justification for the established hypotheses and are inter-connected, as illustrated in the Causal Loop Diagram in

Figure 1, demonstrating the influence of systemic characteristics on each other [

17]. For example, characteristics such as adaptability and equality in the case of time banks are excluded from

Table 1.

Accessibility: TBs are open to anyone, fostering inclusivity by welcoming diverse individuals with various offers, backgrounds, and limitations. This diversity is crucial to maintaining a dynamic and vibrant TB system.

Adaptability: TBs consider legal, cultural, language, and social factors [

5].

Affordability: While some TBs may require a symbolic fee, most are free, ensuring affordability. This fee, if present, is not a significant barrier to participation.

Autonomy: Although TBs operate under a “Base Organization”, the co-production imperative ensures that TB objectives align with societal problem solving [

17].

Credibility: The existence of any TB relies on mutual trust, with credibility determining the success and longevity of the system. Failure in certain contexts can make restarting time banking challenging [

34].

Customizability: This technical term, akin to adaptability, encompasses digital solutions for platforms.

Complexity: While inherently complex due to human connections, TBs can be analyzed by identifying separate system entities, facilitating specific interactions.

Efficiency: Within TBs, the optimization of time and resources in work processes is guaranteed [

17].

Emergence: TBs bring like-minded individuals together to create initiatives that might not occur outside of the TB framework.

Equality: Fundamental to TBs, exchanges occur on a 1:1 basis, ensuring equality in all offers and requests. This principle is inherent to the TB concept.

Evolvability: From its origins and by advocating and endorsing policies from one individual to another, the development of time banks has taken diverse forms, shaped by the specific characteristics of its members. This has resulted in the emergence of the most innovative models that are individual-oriented yet possess organizational significance [

17].

Interoperability: TBs share the same internal makeup, enabling them to be inter-connected into networks.

Modularity: Certain parts of a TB can be added as needed, allowing for flexibility in the system’s structure. For example, a coordinator, although recommended, is not mandatory for a TB’s existence.

Predictability: Operating on a TB system can introduce fluidity, albeit influenced by human behavior.

Sustainability: Meeting basic requirements, including funding and external inputs, ensures a TB’s sustainability as a system [

17].

Tailorability: TBs meet the requirements of established organizations while also catering to the individual needs of the TB’s community members, ensuring the optimal stimulation of all activities conducted by citizens.

Transparency: TBs establish explicit and transparent guidelines for all participants in a TB; clear regulations and the presence of a coordinator enhance the transparency of the TB system.

Universality: TBs can be universally applied as a result of their adaptability, customizability, and tailorability features.

Simulation components, following the mentioned methodology, specifically the Causal Loop Diagram (CLD), enables the modeling of time banks based on qualitative organization variables, as well as their quantitative modeling and orientation towards an innovative definition of the type of time bank. This process is illustrated in

Figure 2 below.

The examination of members’ behavior within the metasystem is meticulously scrutinized and presented through the specialized methodology of TBs [

17]. The inference drawn from employing this model is that, at the level of time banks, an increase in the number of active members leads to a more intricate system due to the distinct needs of everyone, making accessibility more challenging and rendering the credibility of the TB system vulnerable or diminishing. By following this diagram, both the positive aspects of TBs and their vulnerabilities or negative elements can be emphasized. In the modeling process (

Figure 2), factors related to accessibility and innovation, which may be inversely proportional to control elements and transparency, are distinctly highlighted.

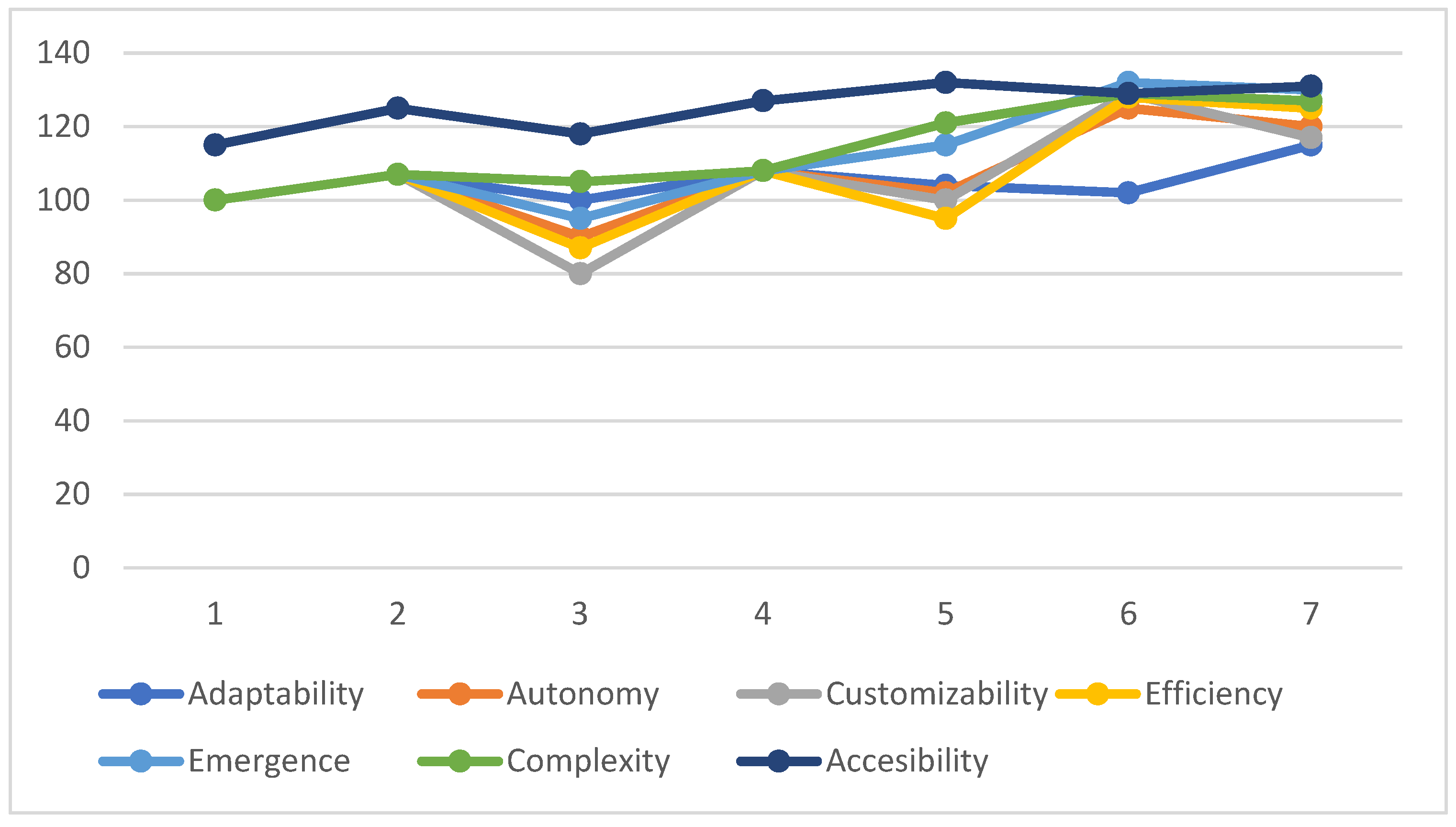

As previously mentioned, the intricacy of the system within time banks (TBs) is a noteworthy attribute, particularly considering how the TB metasystem is tailored to individual needs. This often constrains the development of TB due to the resulting complexity, which introduces certain risks and vulnerabilities. However, as evident in the structure of a TB’s specific characteristics, complexity is intrinsic, playing a role in enabling the TB to fulfill its intended purpose (

Figure 3).

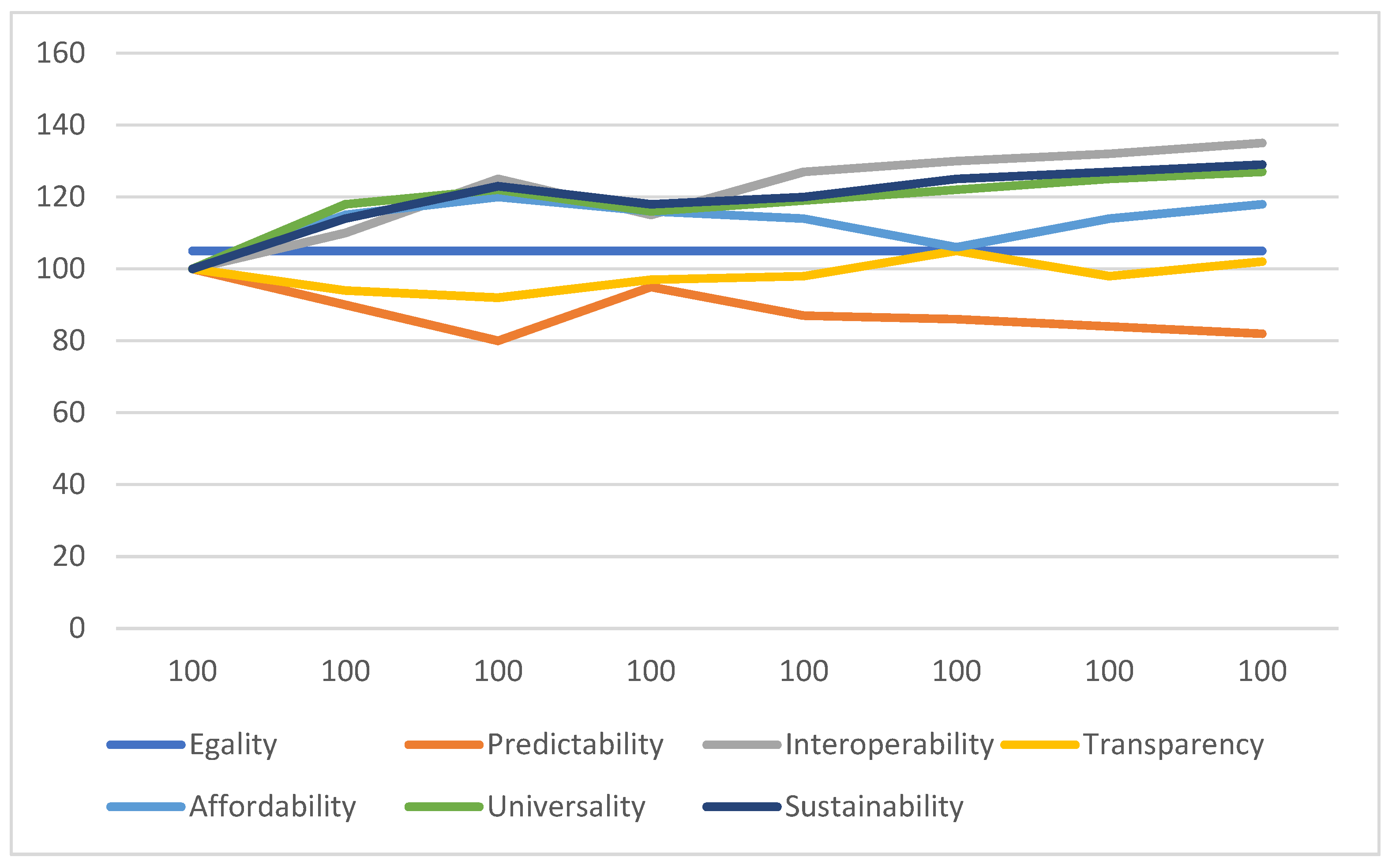

The identified outcomes shed light on multiple aspects, emphasizing that the more intricate a TB becomes, the greater the challenges in terms of predictability and transparency (

Figure 4). In a balanced scenario, the metasystems of TBs are highlighted as having network-type connections, fostering a balanced development aligned with the specific needs of communities of individuals who are direct beneficiaries of TBs.

3.2. Setting Focused on Sustainability

Sustainability is a fundamental attribute within the time bank (TB) system. However, in the context of the specific TB model, sustainability does not exhibit significant oscillations or fluctuations; instead, it remains consistently stable. This stability is influenced by the fact that sustainability at the TB system level is an intrinsic characteristic that cannot be directly influenced. Rather, it results from multiple interactions among various characteristics. The sustainability of a TB metasystem is achieved through a continual and balanced equilibrium among the other specific characteristics inherent to a TB. Maintaining the sustainability of a TB requires a delicate balance among the various other features.

Based on the variables identified within the Valek, L. and Bures, V model that were highlighted above, we can say that the first hypothesis is confirmed; that is, it is based on variables such as accessibility, adaptability, personalization, and efficiency, which enables time bank participants to diversify the way they invest their time and skills, replacing or supplementing traditional money transactions.

Hypothesis no. 2 is supported by variables such as accessibility (a symbolic fee), through which time banks allow for access to resources without using money, and evolvability, the appearance of the most innovative models that are oriented towards the individual but have organizational significance. Moreover, through the variable universality, we appreciate that the hypothesis is confirmed; used in communities where access to money is limited, the time bank can be applied universally, deriving from its characteristics of adaptability, customization, and adaptability.

Regarding hypothesis 3 being established, this is supported by the variables credibility (the existence of any TB is based on mutual trust, credibility, determining the success and longevity of the system regarding the encouragement of community collaboration through time banks, such as the promotion of community collaboration and solidarity), equality (fundamental for a TB, exchanges take place on a 1:1 basis, ensuring equality in all offers and requests), and, last but not least, accessibility (TB is open to anyone, promoting inclusion by welcoming diverse people with different offers, backgrounds, and limitations. This diversity is crucial to maintaining a dynamic and vibrant TB system). All these variables support the hypothesis of the fundamental role of time banks through which people can come together to help each other and create an economic system based on more personal and trusting relationships.

Hypothesis 4 brings together variables such as adaptability (TBs taking into account legal, cultural, linguistic, and social factors), customization (digital solutions for platforms), efficiency (the optimization of time and resources in work processes within TBs), and, ultimately in turn, the variable transparency (establishing explicit and transparent guidelines for all TB participants, clear regulations, and the presence of a coordinator, thus increasing the transparency of the TB system) and the variable universality (TBs can be applied universally, deriving from its characteristics of adaptability, customization, and adaptability). All of these variables that are specific to hypothesis 4 contribute to the definition of this innovative financial instrument, which can evaluate time as a form of value; time banks thus emphasize the importance of contributing to the community. Moreover, through these financial instruments, a special contribution can be made to the process of different evaluations of work and services and in the elimination of different discrepancies between remunerations for the same activities performed.

Reducing money dependence is a specific component of hypothesis 5, and among variables that are related and support this working hypothesis, we mention the following: complexity (the identification of separate entities of the system, facilitating specific interactions), efficiency (the optimization of time and resources in the work processes within TBs), adaptability (meeting the requirements of established organizations while also responding to the individual needs of TB community members, ensuring the optimal stimulation of all citizen activities), transparency (establishing explicit and transparent guidelines for all TB participants, clear regulations, and the presence of a coordinator, which increase the transparency of the TB system), and universality (TB can be applied universally). These variables support the working hypothesis that time banks give people the opportunity to obtain what they need without needing money or falling into debt.

Moreover, to have a clear picture of the existing time banks (at the beginning of the road, from the point of view of financial innovation), in addition to the key variables that define them, it is important to highlight how these time banks are structured depending on the main exchanges made at the level of a time bank. In what follows, we will try to capture some of these defining elements.

3.3. What’s Happening to TimeBanks.org?

In the pursuit of societal well-being, the time bank model has been deemed a potential contributor to the welfare of individuals within specific communities, sectors of activity, and various social or professional groups to which individuals belong. The primary advantage of time banks lies in their optimization of resources, encompassing financial, human, material, and informational resources. While this conceptualization of time banks has been a prevailing constraint, recent developments indicate notable outcomes, especially in the context of multiple crises and contemporary challenges. The results achieved in the recent period merit thorough analysis by the authorities responsible for managing community assets.

Time banking transcends mere group participation, evolving into a distinctive method of community building founded on trust, where members rely on mutual support. Functioning as a mechanism for giving and receiving, time banking fosters the establishment of robust support networks, where one hour of assistance earns an individual one credit.

This approach encourages a return to values surpassing monetary considerations, prioritizing aspects like family, social justice, and the preservation of democratic processes. As participants in a time bank, individuals, groups, or organizations accumulate time credits by fulfilling requests for assistance from others, which can later be redeemed for the support they require.

Whether the exchange involves yard work, medical care, transportation, minor home repairs, computer support, grocery pickup, or meal preparation, all contributions are regarded as equally valuable, measured solely by the time invested in providing them. Offering an hour of service equates to receiving a single credit—a one-to-one exchange where no monetary transactions occur; only time is exchanged.

Time bank members have the autonomy to choose the services they wish to offer or request, ensuring a straightforward and egalitarian process. These exchanges maintain equality, with their value determined solely by the time invested in the activity.

3.4. There Are Four Primary Types of Time Bank Exchanges

One-to-One Exchange: Involves a trade between two individuals. For instance, Artika reads a story, earning time credits, which she subsequently redeems for Daiki’s guitar lessons.

One-to-Many Exchange: Occurs when one person helps multiple individuals. For example, Jose earns credit by planting a small garden, benefiting several members of the community.

Many-to-One Exchange: Involves multiple community members collaborating to assist one individual, such as collectively cleaning a community member’s home for the holiday season.

Many-to-Many Exchange: Encompasses a scenario where numerous individuals collaborate to assist various others, such as a community group planning, organizing, and executing an annual carnival for the enjoyment of all.

All time banks comprise members who agree to exchange services. Individuals, groups, organizations, agencies, churches, and businesses can all be members of a time bank. Members must apply to join the time bank. Local time bank access gives members the opportunity to exchange their time credits on its global platform.

Edgar’s Five Values for Successful Time Banking.

Asset: Recognizes the inherent value everyone possesses to share with others.

Redefining Work: Recognizes types of labor that may not be easily remunerated with currency—significant contributions.

Reciprocity: Shifts the focus from “How can I help you?” to “Will you help some-one, too?” Encourages a culture of paying it forward, fostering collective efforts to build a shared world.

Community/Social Networking: Highlights the importance of building communities through mutual support, strength, and trust. Emphasizes community development by establishing roots, building trust, and creating networks through collaborative efforts.

Respect: Identifies respect as the heart and soul of democracy. Advocates for acknowledging and appreciating individuals for their current state, not just hopeful future aspirations. Contrasting the global market’s tendencies, Edgar champions an economy rewarding decency, care, civic participation, and continuous learning.

Edgar’s concept is straightforward: one hour equals one credit, valuing every hour, human being, and contribution equally. This forms Edgar’s legacy, and

TimeBanks.org is dedicated to honoring and building upon it.

Time banks vary in size, with some supporting only a few members and others spanning thousands. Smaller time banks may face challenges with funding and re-sources, and TimeBanks.Org provides support through educational programs, connections with like-minded time bankers, and software to assist in community building.

Time banks can range from local groups to large organizations, managed by single or multiple coordinators. The structure and focus of a time bank are shaped by the choices of its founders, emphasizing the vital role played by the individuals who drive them forward.

In the words of Margaret Mead, “Timebanks vary from place to place and mission to mission”. Starting a time bank is akin to embarking on a great journey, requiring planning, preparation, and commitment. Leadership and funding are essential ingredients for most time banks, and considerations for preferred leadership approaches and support plans are crucial.

Leadership structures in time banks vary, with some led by a single coordinator, others sharing this role, and some relying on members to actively manage exchanges. Funding models differ, with coordinators earning time credits for their invested hours or, if funds are available, receiving part-time payment. Funding may come from member donations, fundraisers, sponsorships, or partnerships with organizations that share a common mission.

For those contemplating starting a new time bank, “Gathering with a Purpose” offers an action-based workshop to explore time banking before making a commitment. Guides and materials are provided for free download, facilitating an understanding of time banking principles through hands-on experience.

3.5. Time Banking Worldwide

Time Banking in Great Britain

In 1998, time banking was established in England, specifically in Stroud. Subsequently, in 2002, Simon M. founded a time bank identified by the acronym TBUK, drawing inspiration from the flourishing time banking movement in the United States. Functioning as a charitable organization and membership entity, TBUK offers guidance, resources, software, and training for those interested in initiating a community time bank, enhancing existing ones, or deepening their understanding of time banking principles.

TBUK not only serves as a support system for time banks but also actively advocates for time banking at governmental and policy levels in the UK. The organization encourages the adoption of an asset-based approach by supporting entities in incorporating this philosophy into their practices. As of March 2021, TBUK members had collectively exchanged nearly six million hours.

In 2013, Time Republik introduced the Global Time Bank, marking a significant advancement by removing the geographical restrictions that were prevalent in earlier time banks. Since 2015, Time Republik has played a pivotal role in advocating for time banking within companies, local administrations, municipalities, universities, and major corporations.

As emphasized throughout this study, time banks contribute to social well-being through their conceptual definition. Among the numerous works in the specialized scientific literature, we underscore the contributions of authors who provide valuable insights and knowledge [

35].

We appreciate the innovative time bank financial instrument as being able to combine, on the one hand, the specific elements of the traditional time bank concept combined with the specific instruments of platform-type digital financial technologies, as can be seen in the figure below (

Figure 5).

A time bank is an innovative financing opportunity for citizens and small businesses, including start-ups. Especially in the context of the digital era, this innovative financing tool allows individuals and small companies to identify financial resources for their projects with societal impact that need financing by connecting them with investors/financial institutions through an online platform. Investors/financial institutions, in return, receive profits/interest for their investment/placement.

The time bank model, as an innovative financial instrument, can be defined as an efficient tool for the graphical representation of resources, activities, and time within a project, organization, or at the local community level. Moreover, through this model, available resources, activities, and time can be managed, facilitating efficient planning and allocation, thereby contributing to local well-being.

A graphical representation of the time bank model can be seen in

Figure 6 below:

The graphical representation (

Figure 6) of the time bank model was based on three beneficiaries of the time bank model directly involved in carrying out three activities performed within allocated time intervals of 1 h, 2 h, and 3 h (See

Table 2 for details).

The time bank model proves to be an innovative and efficient financial tool for the graphical representation of resources, activities, and time, whether within a project, organization, or at the local community level. The use of this model allows for optimal management of available resources and time, thereby facilitating more efficient planning and allocation. These benefits directly contribute to the enhancement of local well-being.

Figure 6 illustrates the graphical representation of the time bank model, based on the activities of three individuals involved in carrying out three distinct activities, each conducted within time intervals of 1, 2, and 3 h. This visual representation clearly highlights how resources and time can be managed to maximize efficiency and outcomes.

3.6. Discussion on Banking Industry

Innovative financial instruments are often sources of financial risks, which makes their specific regulation necessary, like that applicable to banking institutions. A relevant example is the study conducted by [

36], which examines the impact and effectiveness of liquidity risk support in financial institutions in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. The authors analyze an extensive set of financial and economic data and evaluate the measures implemented by banks in this region to manage and mitigate liquidity risks. They also explore the role of financial regulations and liquidity management strategies, highlighting both their successes and limitations within the specific economic context of the MENA region. The results suggest that, although significant measures have been implemented, major challenges remain in ensuring adequate support for liquidity risks, with important implications for financial stability and future economic policies. This research leads us to assert that, in the context of innovative financial instruments such as time banking, regulation is essential. Additionally, we believe that the indicators identified in the specialized scientific literature can serve as a useful starting point for both our study and future research in the field. Time banks are appreciated as innovative financial instruments for local communities; however, how these specific instruments will be financially supported is very relevant. A relevant study that analyzes the impact of capital empowerment on the lending competence of financial institutions, using a segmental analysis to provide detailed insights, is the one by [

37]. This study evaluates how variations in capital levels influence the financing capabilities and performance of these institutions across different market segments. The analysis employs advanced econometric techniques to assess the relationship between capital endowment and financing practices, considering various contextual factors that may affect this dynamic; these techniques could be relevant for defining the specific model of time banks. Furthermore, the study by [

37] highlights the importance of capital adequacy in enhancing the ability of financial institutions to extend credit effectively, with implications for regulatory policies and financing strategies aimed at supporting financial stability and economic growth. However, it is important to emphasize the unique aspect of this innovative financial instrument, time banks, given that “time” represents the evaluated financial resource that contributes to the sustainable development of local communities, as highlighted throughout our study.

4. Conclusions

This paper possesses practical application potential by providing a structured overview that can assist both theorists and practitioners in understanding the dynamics propelling the various forces within time banks (TBs). A collaborative economy and time banks share commonalities, offering avenues for effective collaboration to sustainably exchange resources, services, and knowledge within communities [

38]. Key areas of complementarity include the following.

By correlating the variables identified with those specific to the model that are identified as most relevant, which define and are related to time banks, key areas of complementarity and specificity in the time bank model and in the collaborative economy model can be noted, listed as follows:

Resource sharing: both the collaborative economy and time banks center around the concept of sharing resources and services. While the sharing economy utilizes online platforms for exchanges, strategic planning of management, and innovations [

39], time banks introduce a temporal dimension by facilitating services based on time.

Building community: emphasizing the importance of community, both the sharing economy and time banks foster social relations and mutual trust through shared resources and time.

Resource utilization efficiency: both concepts advocate for resource utilization efficiency, with the sharing economy focusing on physical resource sharing and time banks prioritizing time as the primary resource.

Sustainable approach: the collaborative economy and time banks contribute to a more sustainable approach by reducing the need for excessive production and consumption through resource and service exchanges.

Use of technology: technology plays a crucial role in facilitating and managing exchanges in both concepts. Online platforms connect individuals for resource and service transactions [

40], yet challenges such as equitable valuation must be addressed for a well-functioning system. When managed appropriately, the collaborative economy and time banks can enhance community connectivity and equity.

The future of research in time banks (TBs) holds promising avenues for further exploration and development. As TBs have evolved over more than 30 years and have garnered attention across various disciplines, there remain several critical areas that warrant in-depth investigation.

Complex Systems Analysis: Future research can delve deeper into the complexities of TBs as a system. Adopting advanced analytical techniques such as network analysis or system dynamics modeling could provide a more nuanced understanding of the intricate relationships within the TB framework.

Integration of Emerging Technologies: With the rapid advancement of technology, exploring how emerging technologies such as blockchain or artificial intelligence can be seamlessly integrated into TB platforms is a promising area. This could enhance the efficiency, transparency, and security of TB transactions.

Global Comparative Studies: Conducting comparative studies across diverse global contexts can offer valuable insights into the adaptability and effectiveness of TB models. Understanding how TBs function in various cultural, economic, and social settings will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of their impact.

Longitudinal Studies: Tracking the long-term impact of TB participation on individuals, communities, and societal structures is essential. Longitudinal studies can provide valuable data on the sustained benefits, challenges, and evolving dynamics within the TB ecosystem.

Policy Implications: Investigating the policy implications of TBs on local and national levels is crucial. Research focusing on how TBs align with or challenge existing economic and social policies can inform policymakers and contribute to the development of supportive frameworks.

Interdisciplinary Approaches: Future research in TBs can benefit from interdisciplinary collaboration, involving experts from fields such as economics, sociology, psychology, public health, and technology. This collaborative approach can provide a holistic understanding of TB dynamics.

Inclusivity and Diversity: Exploring the inclusivity and diversity aspects of TBs is essential. Research can investigate how TBs can better engage marginalized or under-served communities, ensuring that the benefits of time-based exchange systems are accessible to a broader population.

Educational Initiatives: Developing educational initiatives and resources to raise awareness about TBs and promote participation is an area that merits attention. Research can focus on effective strategies for community outreach and education to enhance TB adoption.

Impact on Well-being: Research can delve into the impact of TB participation on individual well-being, mental health, and community cohesion. Understanding the psychosocial dimensions of time-based exchanges can contribute to fostering resilient and connected communities.

In essence, the future of TB research lies in a multifaceted exploration that combines advanced analytical methodologies, technological innovations, global perspectives, and a commitment to addressing societal challenges. The evolving landscape of time-based exchange systems presents a rich terrain for researchers to uncover new insights and contribute to the sustainable development of these innovative socio-economic models.

In this investigation, we delved into the intricate interplay of systemic features within time banks (TBs) and observed how their influence has evolved over time. Despite the inherent complexities associated with analyzing TBs, this study has provided valuable insights into their dynamics and implications for reshaping socio-economic paradigms. However, like any research endeavor, this study is not without its limitations.

The primary limitation stems from the inherent complexity of TBs as metasystems, with numerous integrated subsystems operating within their operational processes. While our initial analysis has provided a structured overview and has optimized the understanding of TB dynamics, further research is warranted to identify additional characteristics and establish more intricate connections within the system. Nevertheless, our findings hold practical application potential, offering both theorists and practitioners a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics propelling TBs. We have identified key areas of complementarity between TBs and the collaborative economy, emphasizing resource sharing, community building, resource utilization efficiency, sustainable approaches, and the role of technology in facilitating exchanges. Moreover, this study incorporates computer-aided simulations and agent-based modeling, marking a departure from traditional approaches in examining TBs. This methodological innovation expands the scope of analysis and provides a more nuanced understanding of TB dynamics.

Looking ahead, the future of TB research holds promising avenues for further exploration and development. Complex systems analysis, the integration of emerging technologies, global comparative studies, longitudinal studies, policy implications, inter-disciplinary approaches, inclusivity and diversity, educational initiatives, and the impact on well-being are all critical areas warranting attention.

Our involvement in the future of TB research may take various forms, including research collaboration, data collection and sharing, community engagement, advocacy for funding, the dissemination of knowledge, educational initiatives, technological integration, policy advocacy, longitudinal studies, and global perspectives. By actively participating in these endeavors, we aim to contribute to the sustainable development of innovative socio-economic models within the TB ecosystem.

In conclusion, while challenges and limitations persist, the evolving landscape of TBs presents a rich terrain for researchers to uncover new insights and shape the future of time-based exchange systems. Through continued dedication and collaboration, we can collectively advance our understanding and foster the sustainable development of TBs in diverse global contexts.