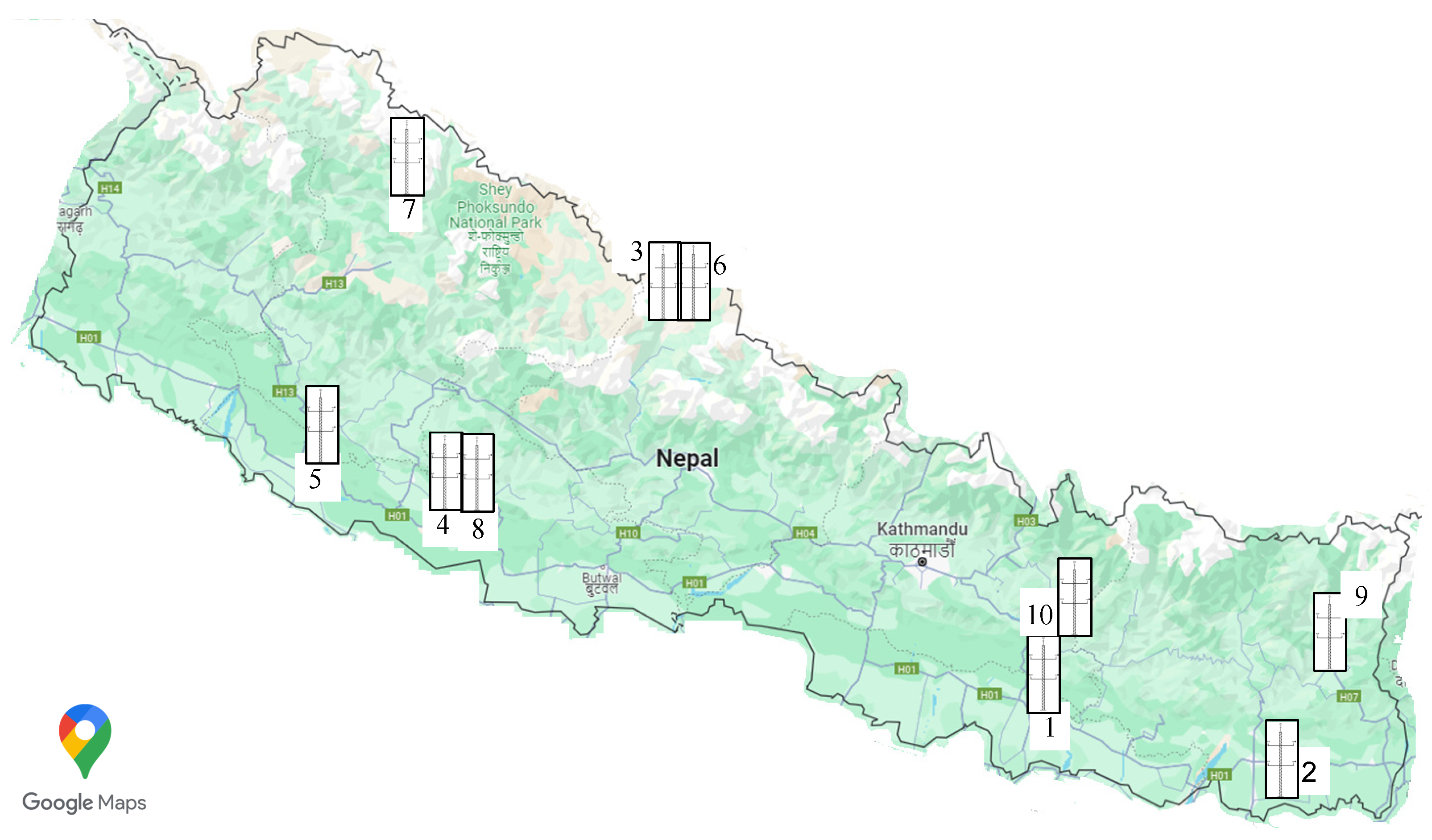

2.1. Measurement Sites

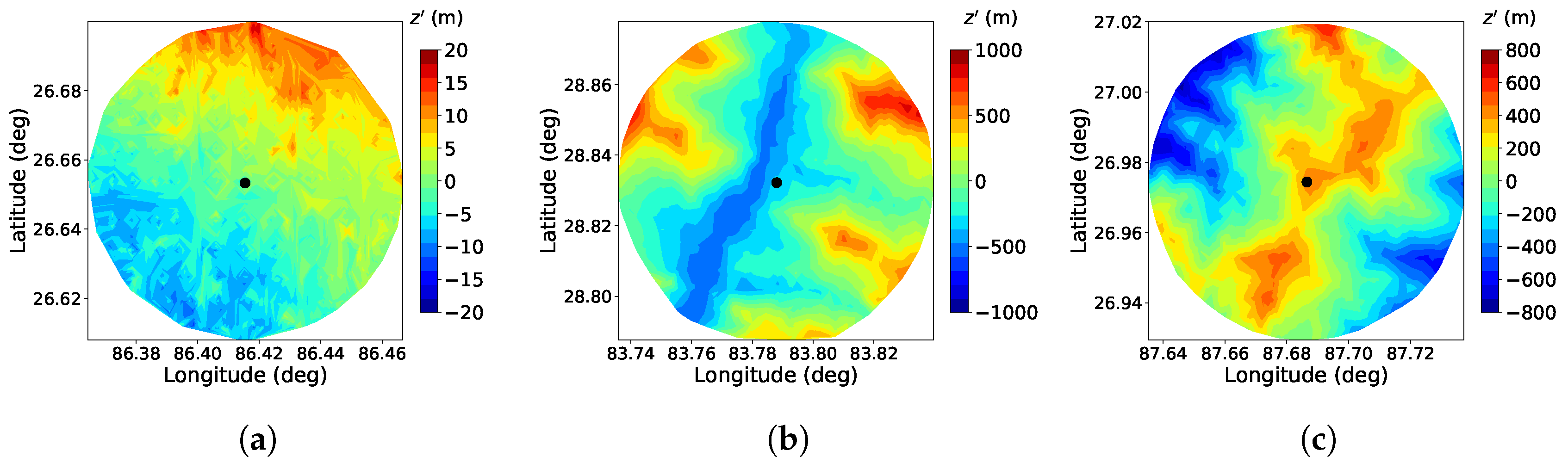

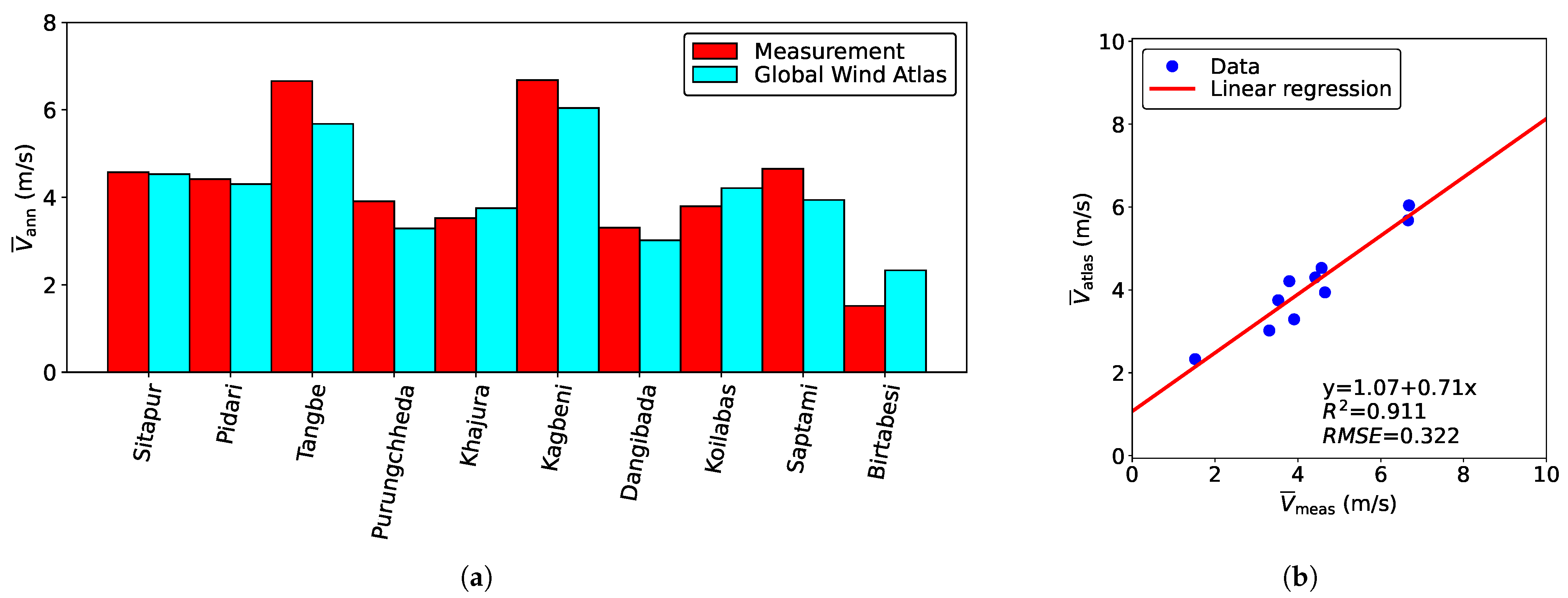

Nepal has one of the most complex terrains in the world. The country extends from northwest to southeast, and, just within the latitude range from around to , the elevation varies from 50 m to more than 8000 m. The southern part of the country is flat, with negligible elevation features, but the mountainous region starts just about 20 to 30 km north of the southern border. Extreme variations in geographical features contribute to the highly localized atmospheric dynamic, especially in the north of the country. The complex terrain and the localized behavior of the atmosphere are the reasons why the wind resources of Nepal cannot be accurately predicted with mesoscale simulation tools such as Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF). Extended and distributed measurement campaigns, which, in addition to providing an actual picture of available wind resources, are necessary to calibrate and improve the performance of simulation tools like WRF.

The Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) funded and supported the project of identifying and geospatial planning of renewable energy resources for Nepal [

10]. The project is administered by the World Bank and has installed 10 meteorological masts (met-masts) in the various regions of Nepal [

11], as summarized in

Table 1. Their rough locations are also shown in

Figure 1, with site numbers corresponding to those in the table. Details about mast installation and instrumentation can be found in the World Bank Report [

11]. All 10 met-masts are composed of square lattice towers supported by guy wires, and they have the height of 80 m. They were designed according to the IEC Standard 61400-12-1. Met-masts are equipped with cup anemometers (Thies 4.3351.10.000) from 20 m through 80 m height at an interval of 20 m, while wind vanes (Thies 4.3151.00.901) are installed at 58.5 m and 78.5 m. Cup anemometers have accuracy class of 0.5 (class S classification). Both cup anemometers and wind vanes collect horizontal wind speeds and directions at a sampling frequency of 1 Hz. The measured data has been publicly available since 2019 in the ESMAP repository via

ENERGYDATA.info [

12]. In terms of terrain complexity, sites 1, 2, 5, 8, and 10 can be considered to have flat terrain, and sites 3, 4, 6, 7, and 9 can be considered to have highly complex terrain.

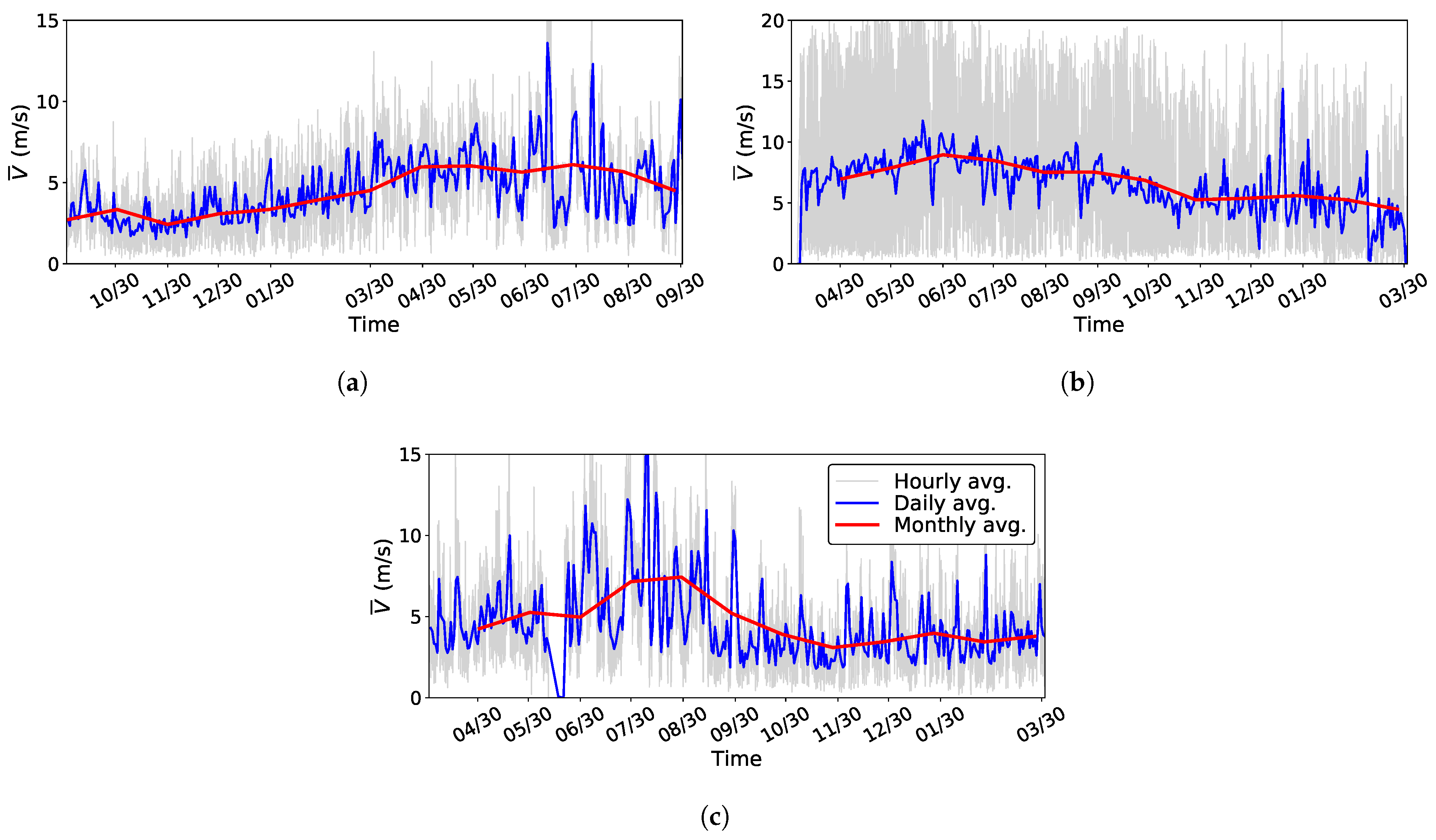

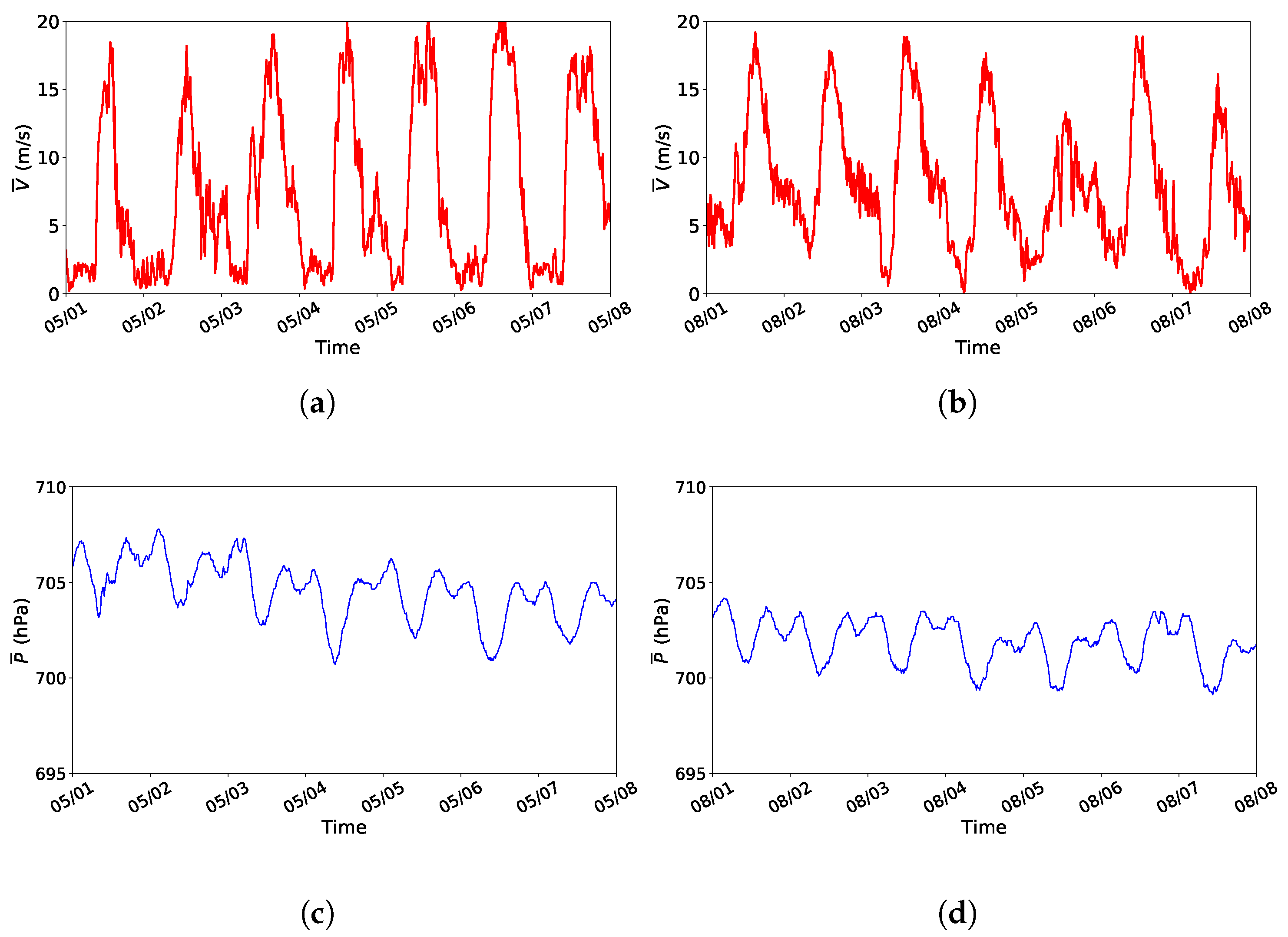

2.2. Data and Methodology

This study uses data from the repository under the open data license terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 [

13]. It is noted that the author was not involved in the actual measurement campaigns. Wind speeds and wind directions data for the period of one year are analyzed from all 10 met-masts. For site number 1 Sitapur, data from October 2018 through September 2019, for site number 4 Purungchheda and site number 7 Dangibada, data from January through December 2019 are processed. For all other sites, data from April 2019 through March 2020 is used. Wind speed and wind direction data at 80 m and 78.8 m, respectively, are primarily analyzed for evaluating wind energy potential at those sites. All analyses are conducted using 10-min averaged data derived from measurements at a 1 Hz sampling frequency. To mitigate the influence of extreme outliers caused by measurement uncertainties, the 90th percentile values of turbulence intensity and peak wind speed are used in the analysis. In addition, mean wind speeds below 0.2 m/s are excluded when calculating the power law exponent (

).

Figure 2 shows the availability (

) of the 10-min average wind speeds during the one-year analysis period.

is defined as [

14]

where

and

are the maximum and the actual number of 10-min averaged wind data that the anemometer can measure in one year. It can be observed that, except for site 3 Tangbe, availability is almost 100% for all sites. Therefore, the data can be considered sufficiently reliable for accurate wind resource analysis. For Tangbe, data was unavailable for approximately six month period, resulting in

η < 50%. However, since sites 3 and 6 are close to each other, lower availability at site 3 does not affect the results and conclusions of this study.

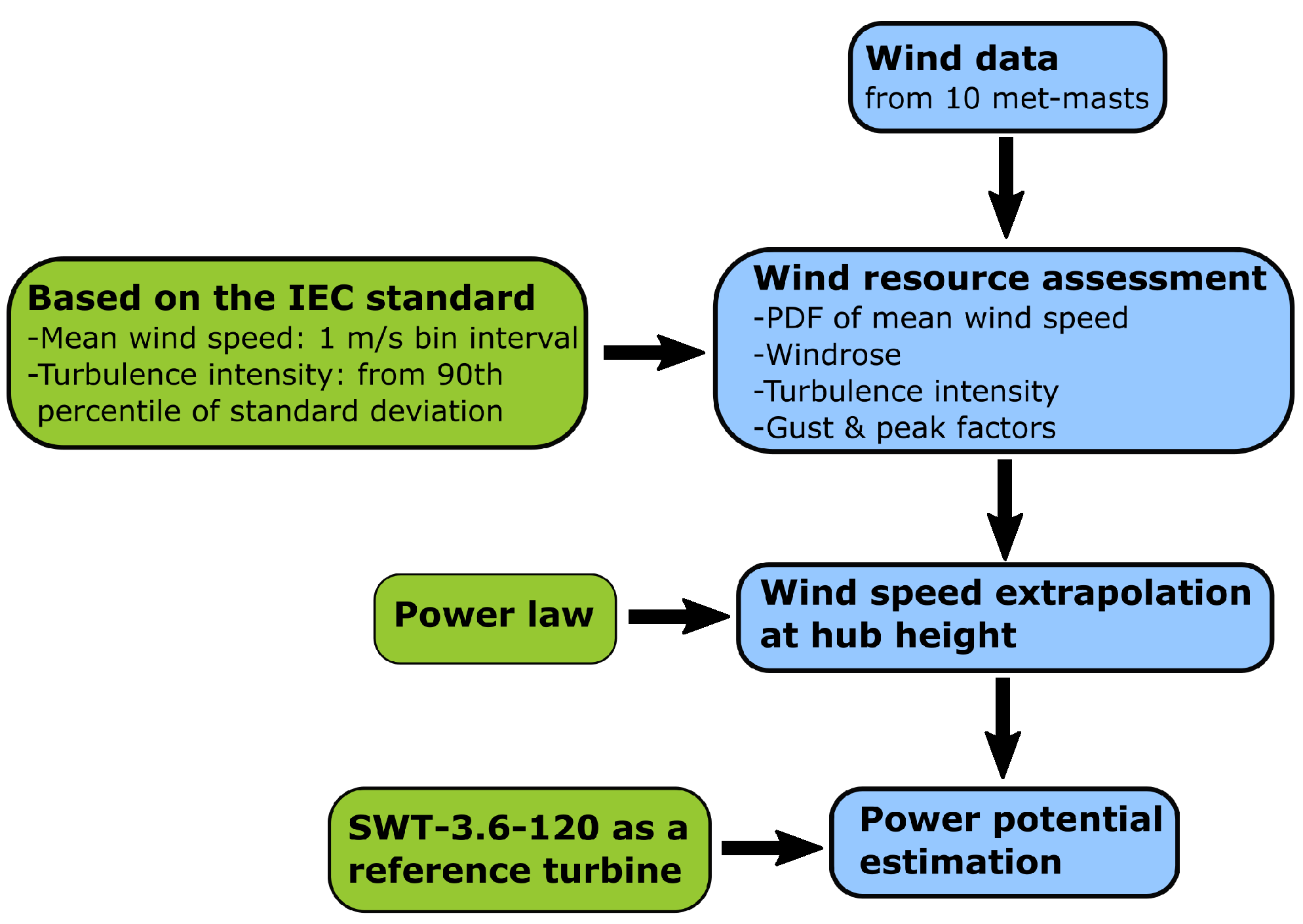

Figure 3 shows the flowchart describing the research methodology employed in this study. Wind resource assessment is performed based on the IEC standard. The methods applied, along with their corresponding formulations, are outlined here.

First of all, the mean wind speed distributions are analyzed using the Weibull probability distribution (PDF), which is defined as

where

k and

c are the shape and scale factors, respectively. Since the Weibull PDF is based on two parameters, it can better represent a wider variety of wind regimes and therefore is also one of the most commonly used probability distributions in wind data analysis [

4].

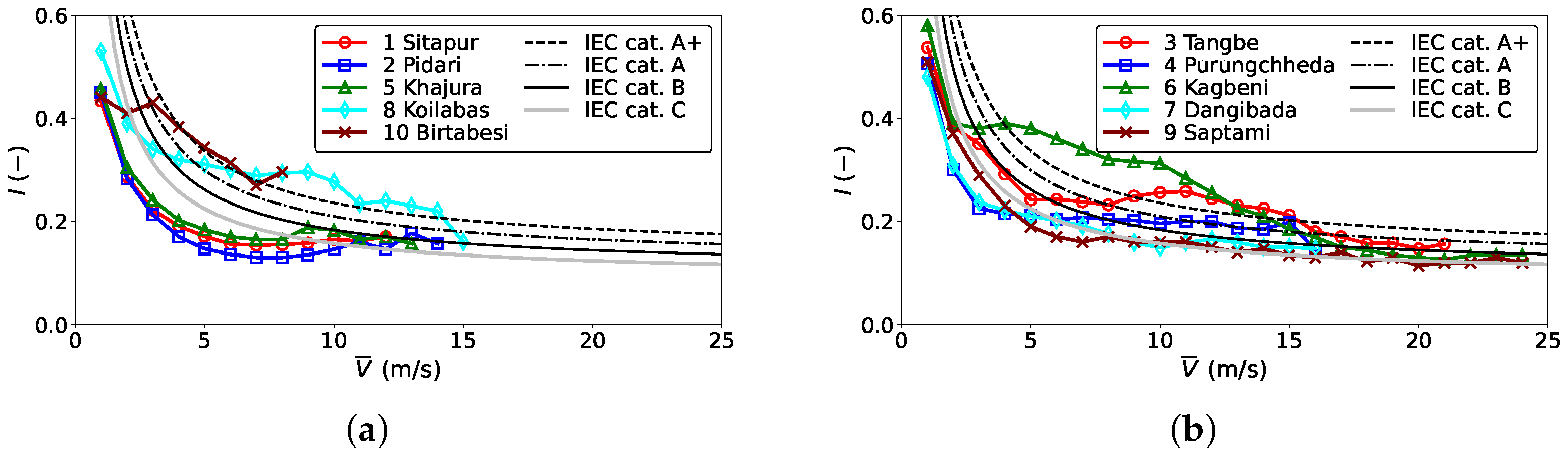

Fluctuations in wind speed are quantified using turbulence intensity (

I), which is the ratio of the standard deviation (

) to the mean wind speed (

):

The study compares the measured turbulence intensities with those specified by the IEC standard. The turbulence intensity profiles in the IEC standard are given by

where

is the reference value of the turbulence intensity,

is the wind turbine hub height wind speed, and

m/s. In the IEC standard,

is defined as the turbulence intensity corresponding to the 70% quantile at 15 m/s. There are four categories of reference turbulence intensities, namely A + (

): very high turbulence; A (

): higher turbulence; B (

): medium turbulence; and C (

): lower turbulence. There is an additional wind turbine class, Class S, for which the wind speed and turbulence intensity are specified by the designer [

15].

Turbulence intensity is also related to ABL stability, which is quantified using the Bulk Richardson number (

) in this study.

is defined as

where

g is the acceleration due to gravity,

is the mean potential temperature,

is the potential temperature difference between vertical levels separated by

, and

is the wind speed difference. By definition,

is negative under unstable stratification and positive under stable stratification. A critical Richardson number of

is commonly used as a threshold above which atmospheric turbulence is suppressed [

16].

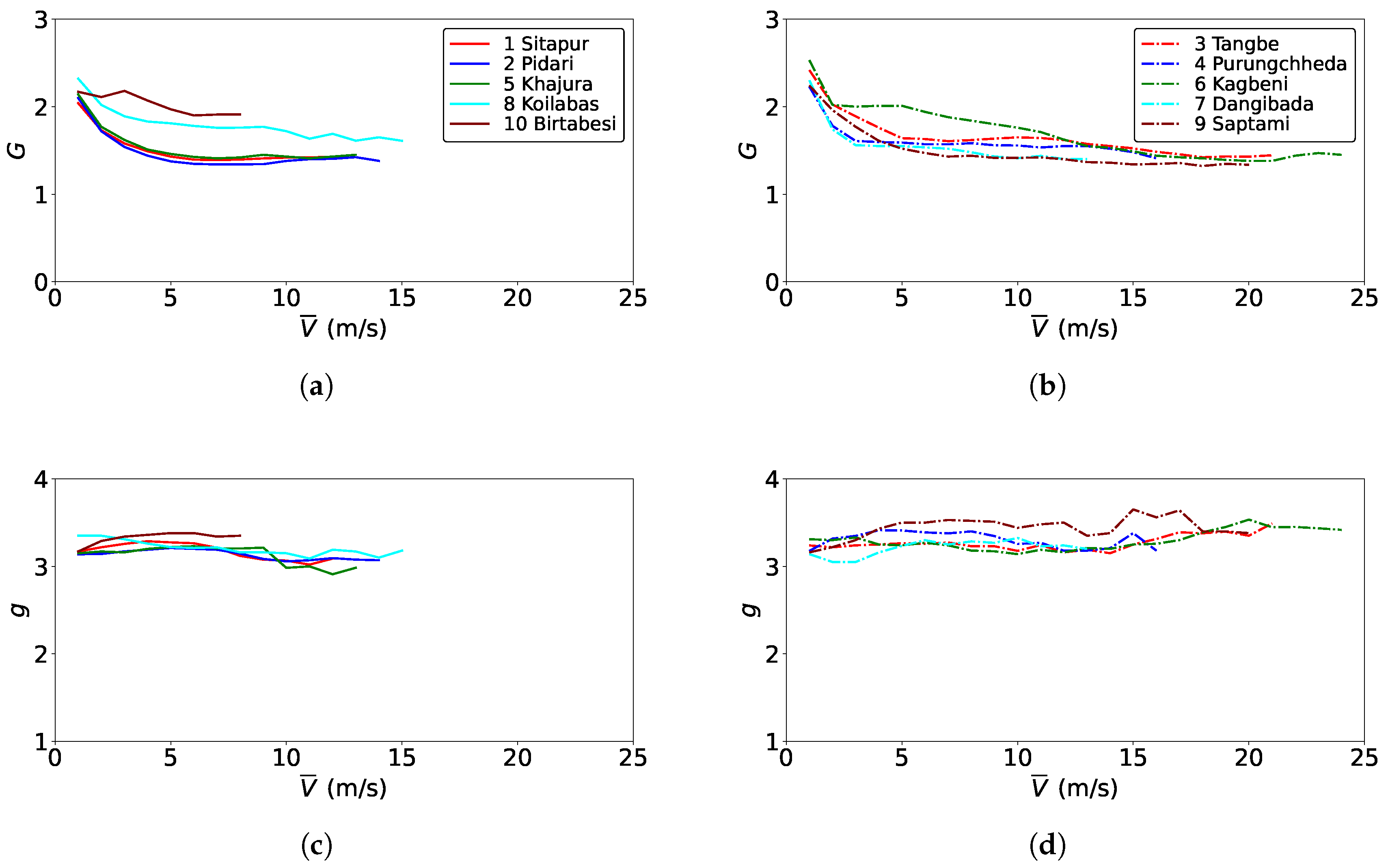

The peak gust wind speeds are required for estimating the extreme load that a wind turbine may experience at the site. To that end, gust factor (

G) and peak factor (

g) are used to define an expected value of peak wind speed (

) as required by the IEC standard [

15].

Here, gust factor

, peak factor

, and

is the standard deviation.

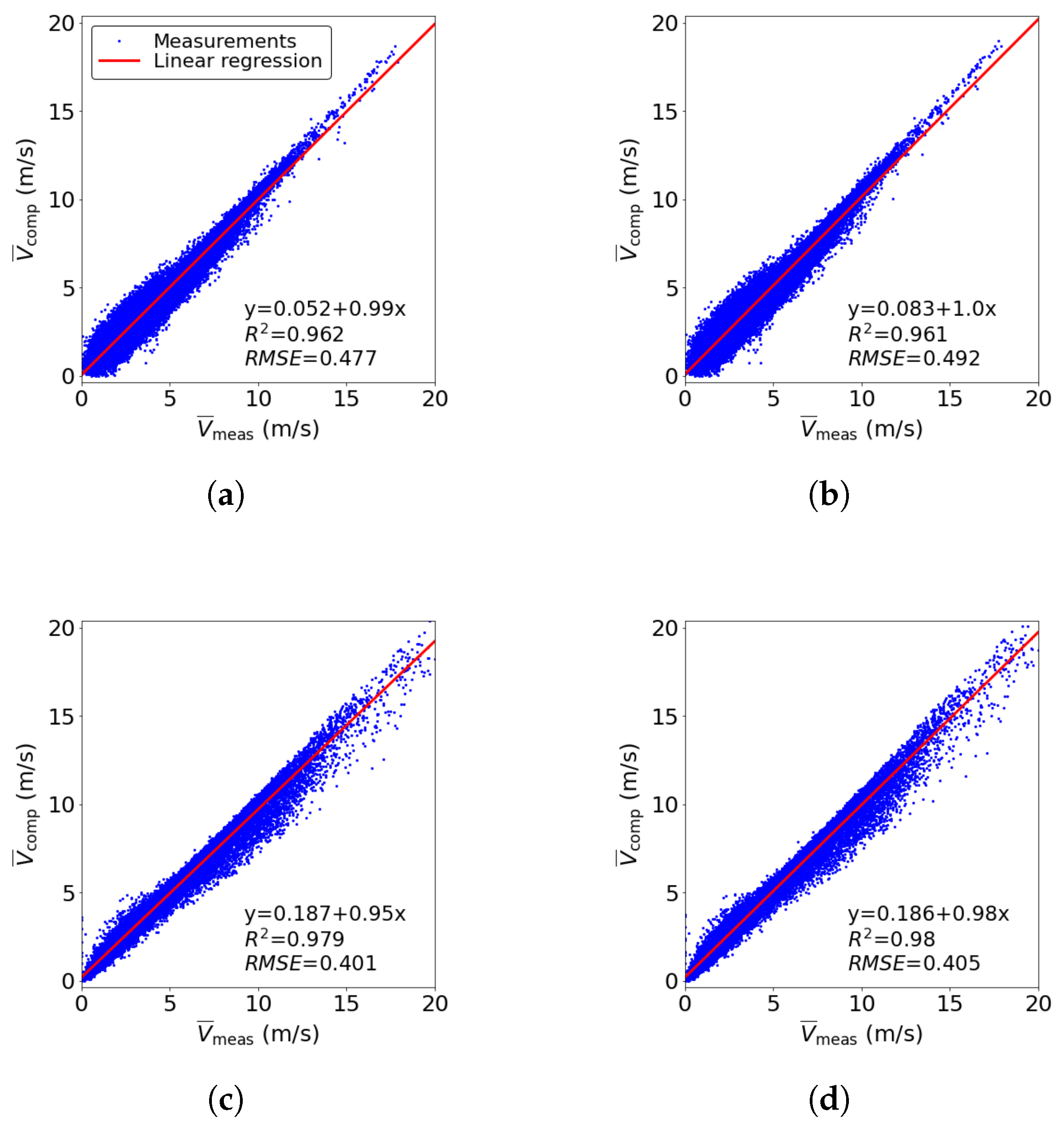

For accurate wind resource assessment, wind speeds at higher points (corresponding to the wind turbine hub height) can be extrapolated using logarithmic or power law profiles; i.e.,

In Equation (

7),

is a friction velocity,

is the von Karman’s constant, and

is the surface roughness height. Similarly, in Equation (

8),

is a reference height at which measured wind speed

is available, and

is a wind speed that needs to be estimated.

is the power law exponent, and its value is strongly influenced by the nature of the terrain, atmospheric stability, and other thermal and mechanical parameters [

17]. Logarithmic profile requires terrain roughness height, which is not always known. The study therefore uses power law representation of wind speed profiles. To that end,

values for each site are computed using wind data at two lower heights using

where

and

are lower heights (80 m or below) for which measurement data is available.

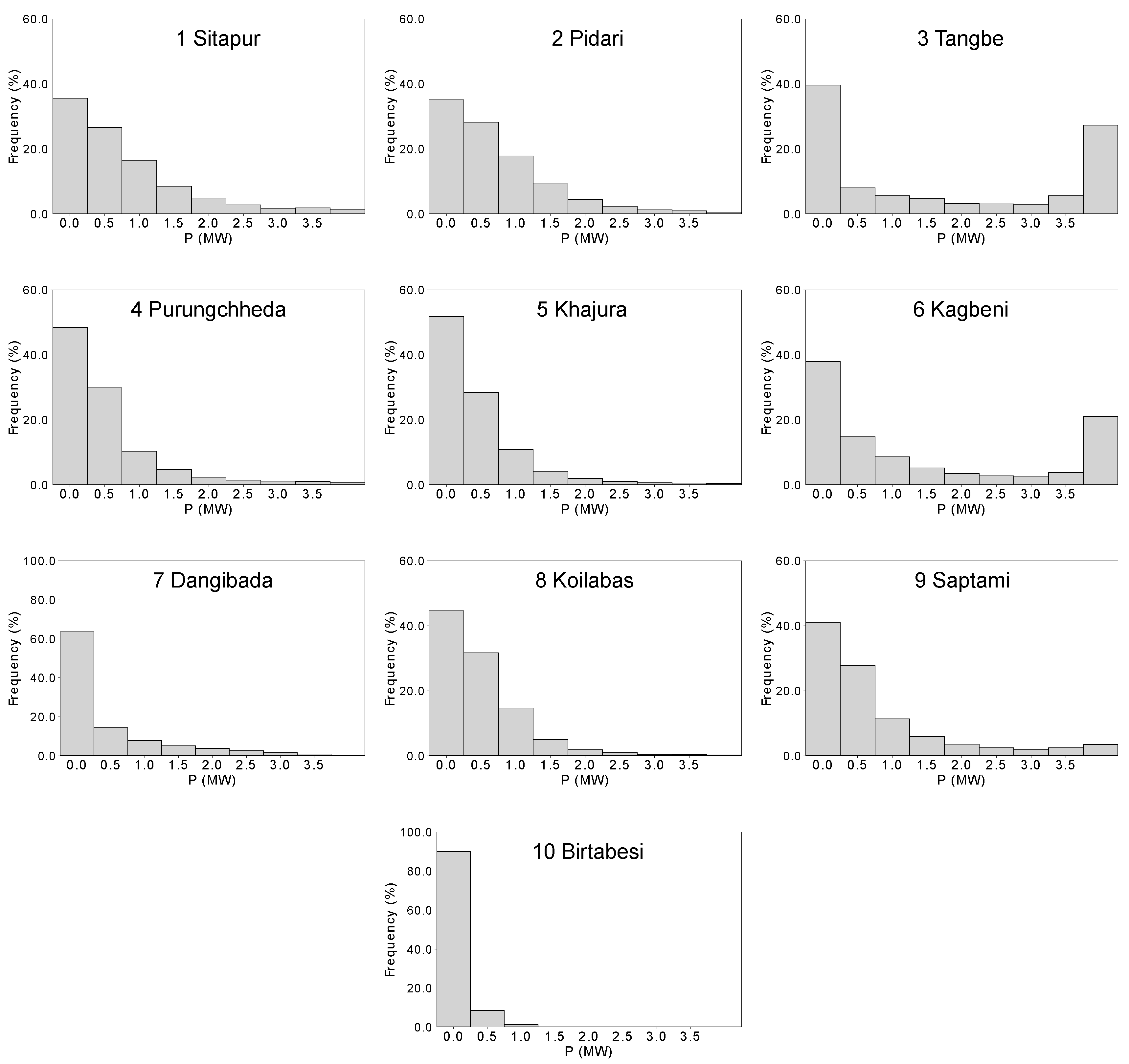

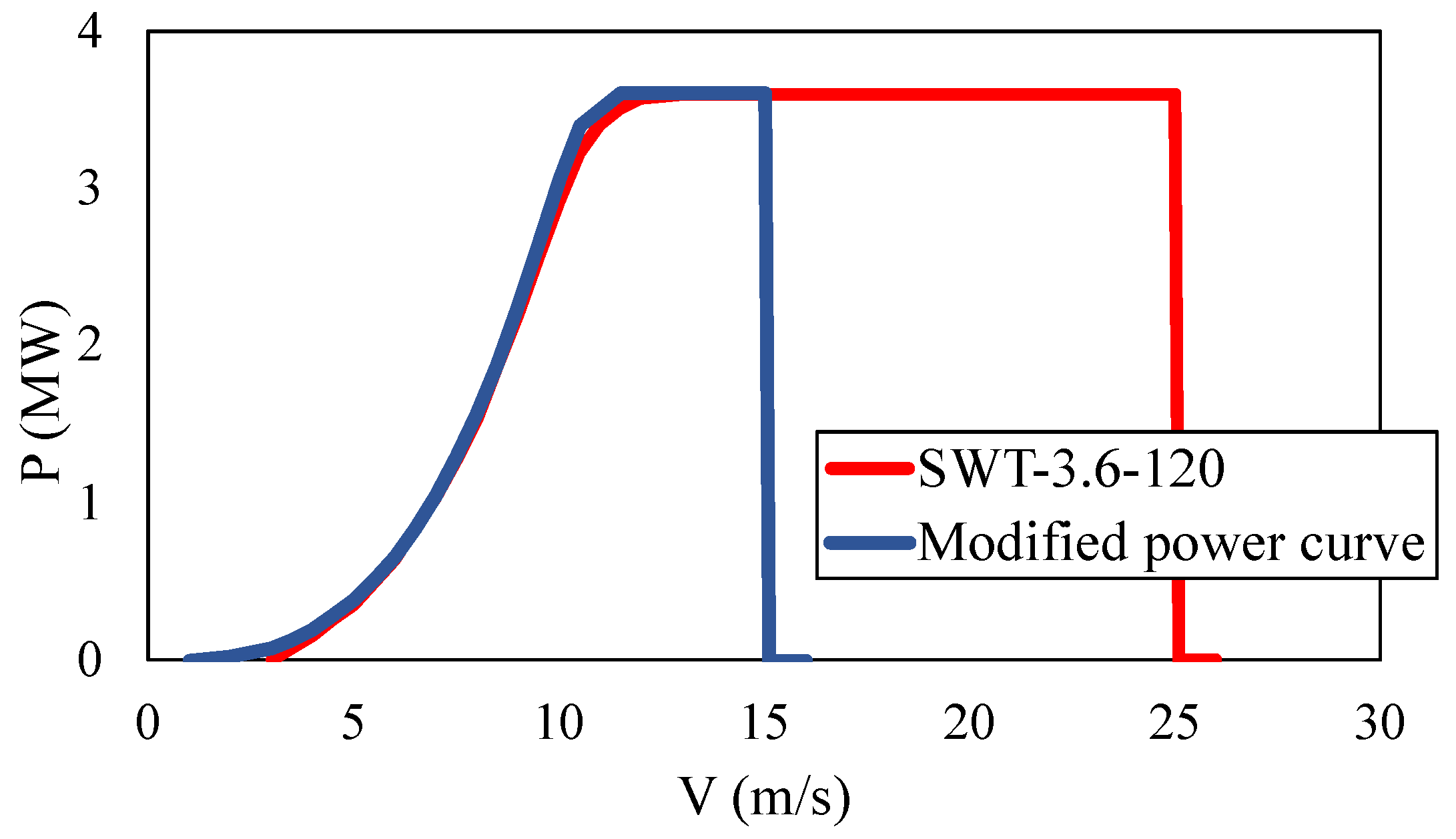

Next, the potential power outputs of the sites are computed using the power curve of SWT-3.6-120 wind turbine. This turbine has a rotor diameter (

D) of 120 m and a rated power (

) of 3.6 MW. Its cut-in (

), rated (

), and cut-out (

) wind speeds are 3.5 m/s, 14 m/s, and 25 m/s, respectively. The power curve and other details about the turbine are accessible at

thewindpower.net [

18]. The power outputs of the sites are computed using

where

and

are discrete power outputs of SWT-3.6-120 at wind speeds

and

, respectively.

The available wind power (

), which is used in power duration curve analysis, is computed using the swept area of the SWT-3.6-120 wind turbine; i.e.,

where

is the air density, and

.