Nutritional Value and Bioactive Lipid Constituents in Seeds of Phaseolus Bean Cultivated in Bulgaria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Chemical Composition of Seeds

2.3. Isolation of Glyceride Oil and Determination of Oil Content

2.4. Analysis of Fatty Acids

2.5. Analysis of Sterols

2.6. Analysis of Tocopherols

2.7. Analysis of Phospholipids

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of Seeds from Four Bean Accessions

3.2. Lipid Composition

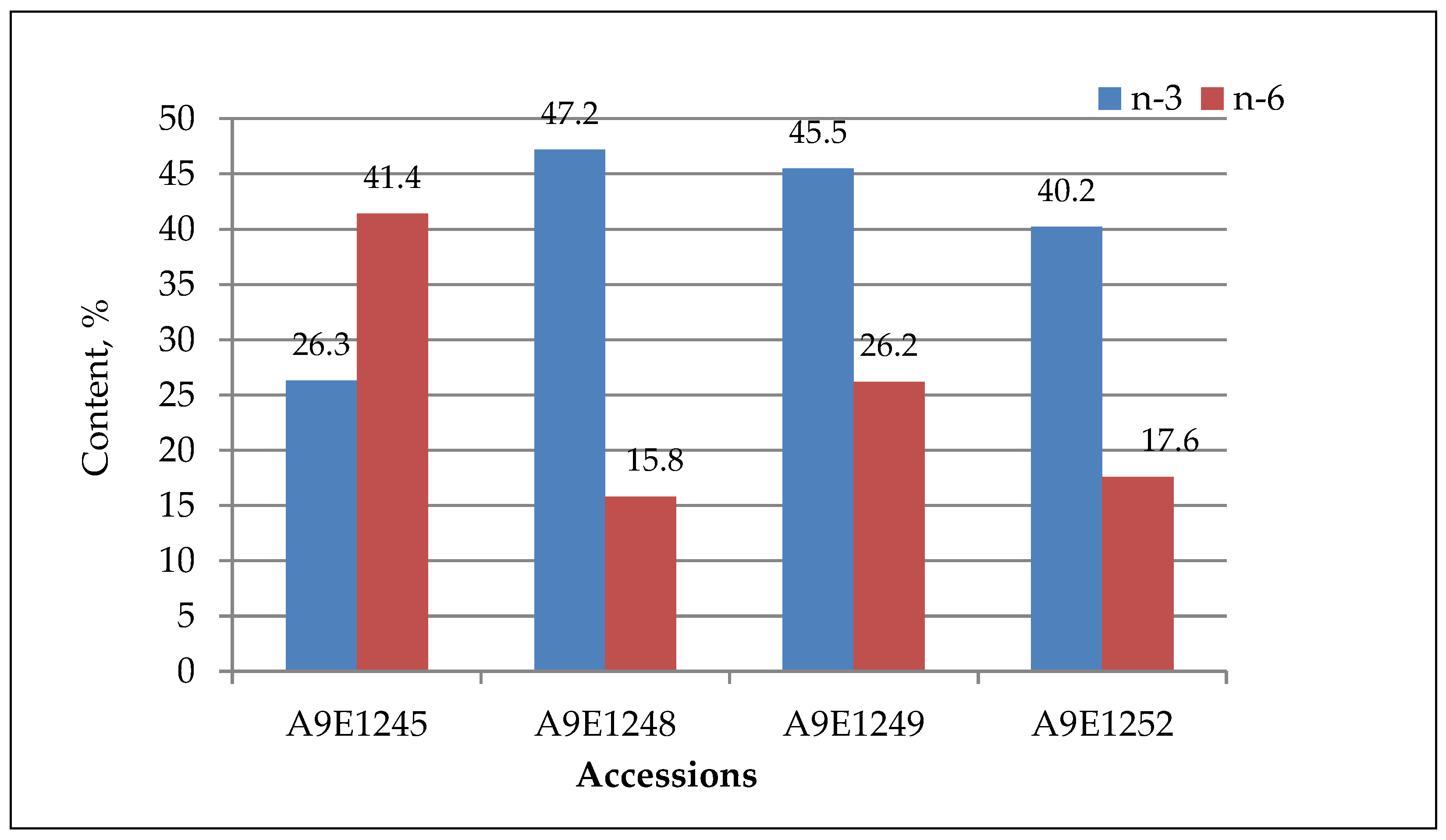

3.2.1. Fatty Acid Composition

3.2.2. Sterol Composition

3.2.3. Tocopherol Composition

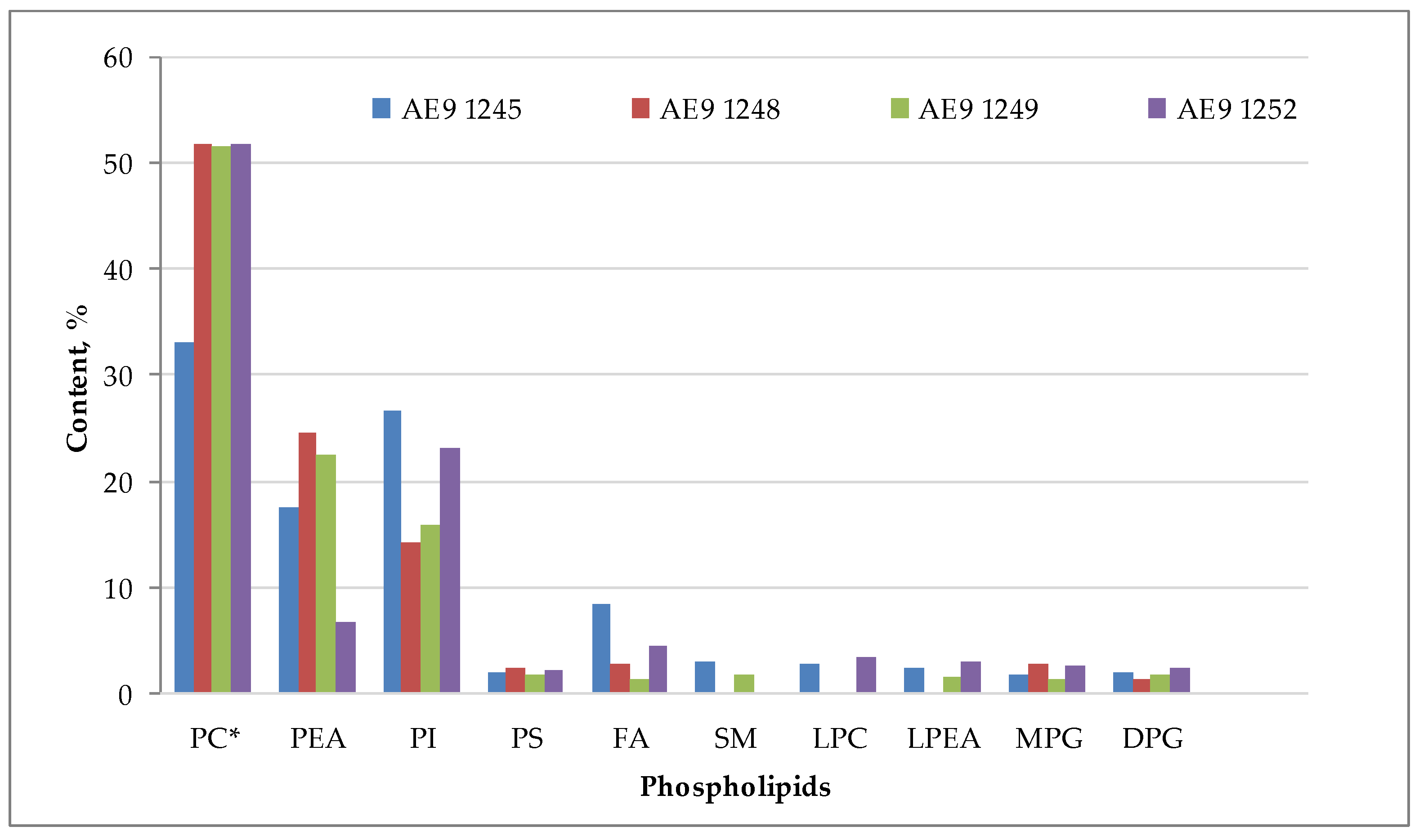

3.2.4. Phospholipid Composition of Lipids

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| IPGR | Institute of Plant Genetic Resources |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| TLC | Thin-layer chromatography |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acids |

| UFA | Unsaturated fatty acids |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acids |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| n-6 | Omega-6 fatty acids |

| n-3 | Omega-3 fatty acids |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PEA | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PI | Phosphatidylinositol |

| PS | Phosphatidylserine |

| PA | Phosphatidic acids |

| SM | Sphingomyelin |

| LPC | Lysophosphatidylcholine |

| LPEA | Lysophosphatidylethanolamine |

| MPG | Monophosphatidylglycerol |

| DPG | Diphosphatidylglycerol |

References

- Alcázar-Valle, M.; Lugo-Cervantes, E.; Mojica, L.; Morales-Hernández, N.; Reyes-Ramírez, H.; Enríquez-Vara, J.N.; García-Morales, S. Bioactive Compounds, Antioxidant Activity, and Antinutritional Content of Legumes: A Comparison between Four Phaseolus Species. Molecules 2020, 25, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitocchi, E.; Nanni, L.; Bellucci, E.; Rossi, M.; Giardini, A.; Zeuli, P.S.; Logozzo, G.; Stougaard, J.; McClean, P.; Attene, G.; et al. Mesoamerican Origin of the Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Is Revealed by Sequence Data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E788–E796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Production: Crops and Livestock Products; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Mauceri, A.; Romeo, M.; Bacchi, M.; Preiti, G. Pheno-morphological, agronomic and genetic diversity in a common bean core collection from Calabria (Italy). Ital. J. Agron. 2025, 20, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, T.; Petrova, S.; Simova-Stoilova, L. Assessment of Morphological Diversity, Yield Components, and Seed Bio-chemical Composition in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Landraces. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Astudillo, M.J.; Tapia, C.; Giménez de Azcárate, J.; Montalvo, D. Diversity of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and Runner Bean (Phaseolus coccineus L.) Landraces in Rural Communities in the Andes Highlands of Cotacachi—Ecuado. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desheva, G.; Valchinova, E.; Deshev, M. Ex-situ Conservation of PGR in the National Seed Genebank of Bulgaria—Past, Present and Future. Bulg. J. Crop Sci. 2022, 59, 3–8. Available online: https://agriacad.eu/ojs/index.php/bjcs/article/view/1832/1703 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Ocho-Anin Atchibri, A.L.; Kouakou, T.H.; Brou, K.D.; Kouadio, Y.J.; Gnakri, D. Evaluation of Bioactive Components in Seeds of Phaseolus vulgaris L. (Fabaceae) Cultivated in Côte d’Ivoire. J. Appl. Biosci. 2010, 31, 1928–1934. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:54035833 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Audi, S.S.; Aremu, M.O. Effect of Processing on Chemical Composition of Red Kidney Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Flour. Pak. J. Nutr. 2011, 10, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpenyong, T.E.; Borchers, R.L. The Fatty Acid Compositions of the Oils of the Winged Bean (Psophocarpus tetragonolobus L.) Seeds. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1980, 57, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Fialho, L.; Guimarães, V.M.; de Barros, E.G.; Moreira, M.A.; dos Santos Dias, L.A.; de Almeida Oliveira, M.G.; Jose, I.C.; de Rezende, S.T. Biochemical Composition and Indigestible Oligosaccharides in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Seeds. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2006, 61, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaydou, E.M.; Bianchini, J.R.; Ratovohery, J.V. Triterpene Alcohols, Methylsterols, Sterols, and Fatty Acids in Five Malagasy Legume Seed Oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1983, 31, 833–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.; Llano, J.; Medina, L.A.; Castellanos, A.E. Chemical Composition in Seeds of Phaseolus vulgaris L., Phaseolus acutifolius and Vigna unguiculata Grown Under Water Stress Conditions. Annu. Rep. Bean Improv. Coop. 1992, 35, 169–170. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/364184773 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Mabaleha, M.B.; Yeboah, S.O. Characterization and Compositional Studies of the Oils from Some Legume Cultivars Phaseolus vulgaris, Grown in Southern Africa. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2004, 81, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, R.K.; Adriana-Nunez Gonzalez, G.Z.Z.; Wesche-Ebeling, P.; Moreno-Limon, S.L. Some Recent Contributions in Seed Structure and Chemical Composition of Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Agric. Rev. 2001, 22, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, F.R.; Corrêa, A.D.; Abreu, C.M.P.D.; Lima, R.A.Z.; Abreu, A.D.F.B. Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Lines: Chemical Composition and Protein Digestibility. Ciência Agrotecnologia 2007, 31, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuliri, V.A.; Obu, J.A. Lipids and Other Constituents of Vigna unguiculata and Phaseolus vulgaris Grown in Northern Nigeria. Food Chem. 2002, 78, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, E.; Galvin, K.; O’Connor, T.P.; Maguire, A.R.; O’Brien, N.M. Phytosterol, Squalene, Tocopherol Content and Fatty Acid Profile of Selected Seeds, Grains and Legumes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2007, 62, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahasrabudhe, M.R.; Quinn, J.R.; Paton, D.; Youngs, C.G.; Skura, B.J. Chemical Composition of White Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and Functional Characteristics of Its Air-Classified Protein and Starch Fractions. J. Food Sci. 1981, 46, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutivisedsak, N.; Moser, B.R.; Sharma, B.K.; Evangelista, R.L.; Cheng, H.N.; Lesch, W.C.; Tangsrud, R.R.; Biswas, A. Physical Properties and Fatty Acid Profiles of Oils from Black, Kidney, Great Northern and Pinto Beans. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars Pineda, M.; Rodríguez Galdón, B.; Paiz Álvarez, N.; Afonso Morales, D.; Ríos Mesa, D.; Díaz Romero, C.; Rodríguez Rodríguez, E.M. Physico-Chemical and Nutritional Characterization of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Germplasm. Legume Res. 2023, 46, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anino, C.; Onyango, A.N.; Imathiu, S.; Maina, J.; Onyangore, F. Chemical Composition of the Seed and ‘Milk’ of Three Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Varieties. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 1242–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poroch-Seriţan, M.; Greculeac, P.M.; Dobrincu, D.S.; Jarcău, M.; Matei, A.L.; Chicaroș, T. Chemical and Physical Characterization of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Landraces by North–North-Western Extremity of Romania. Food Environ. Saf. 2023, 22, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeva, M.; Stoilova, T. Biochemical Evaluation of Some Models Introduced Garden Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) and Vigna (Vigna unguiculata L.). In Proceedings of the Jubilee Scientific Session—50 Years Union of Scientists in Bulgaria, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 20 November 1998; Volume 1, pp. 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Stoilova, T.; Sabeva, M. Chemical Composition of Green Legumes’ Seeds—Beans and Cowpea. Sci. Pap. Univ. Plovdiv “Paisii Hilendarski”, Chem. 2008, 36, 119–126. Available online: http://files.argon.uni-plovdiv.bg/NT/NT36_2008.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Sabeva, M.; Stoilova, T. Biochemical Characterization of Local and Introduced Models Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and Vigna (Vigna unguiculata L.). In Proceedings of the 7th Scientific Conference with International Participation “Ecology and Health”, Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 10 April 2008; pp. 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- Sabeva, M.; Stoilova, T. Chemical Composition of Phaseolus vulgaris L. and Ph. coccineus L. Seeds in Local Germplasm from Troyan Region. J. Mt. Agric. Balk. 2010, 13, 1146–1155. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273772424 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Covaciu, A.; Benedek, T.; Bobescu, E.; Rus, H.; Benza, V.; Marceanu, L.G.; Grigorescu, S.; Strempel, C.G. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Improved Long Term Prognosis by Reducing Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Endothelial Dysfunction in Acute Coronary Syndromes. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Niu, Q.; Ding, S.; Li, W. Effects of phytosterol-rich foods on lipid profile and inflammatory markers in patients with hyperlipidemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1619922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelczarski, M.; Wolaniuk, S.; Zaborska, M.; Sadowski, J.; Sztangreciak-Lehun, A.; Bułdak, R.J. The role of α-tocopherol in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 480, 3385–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murube, E.; Beleggia, R.; Pacetti, D.; Nartea, A.; Frascarelli, G.; Lanzavecchia, G.; Bellucci, E.; Nanni, L.; Gioia, T.; Marciello, U.; et al. Characterization of Nutritional Quality Traits of a Common Bean Germplasm Collection. Foods 2021, 10, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 16th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1996; Method 945.18-B, “Kjeldahl’s Method for Protein Determination in Cereals and Feed”. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; AOAC International: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Food Energy—Methods of Analysis and Conversion Factors; Report of a Technical Workshop; FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 77; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 659; Oilseeds—Determination of Oil Content (Reference Method). International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 12966-2; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters—Part 2: Preparation of Methyl Esters of Fatty Acids. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 12966-1; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters—Part 1: Guidelines on Modern Gas Chromatography. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- American Oil Chemists’ Society (AOCS). Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 5th ed.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 1999; Method Cd 1c-8, “Calculated Iodine Value”. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 18609; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Unsaponifiable Matter—Method Using Hexane Extraction. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- ISO 12228-1; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Individual and Total Sterols Contents—Part 1: Gas Chromatographic Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 9936; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Tocopherol and Tocotrienol Contents by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane-Stanley, G.H. A Simple Method for Isolation and Purification of Total Lipids from Animal Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10540-1; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils—Determination of Phosphorus Content—Part 1: Colorimetric Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- Antova, G.; Stoilova, T.; Ivanova, M. Proximate and lipid composition of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata L.) cultivated in Bulgaria. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014, 33, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauceda, A.L.U.; Ponce–Fernandez, N.E.; Gregorio–Lopez, P.; Rosas–Dominguez, G. Chemical Composition of Different Formulations of Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Sarazo Consumed in Sinaloa. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 6, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los, F.G.B.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Wojeicchowski, J.P.; Nogueira, A.; Demiate, I.M. Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): Whole Seeds with Complex Chemical Composition. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 19, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food Balance Sheets, A Handbook; Annex I, Food Composition Tables; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2001; Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/x9892e/X9892e05.htm (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- CXS210–1999; Codex Alimentarius, International Food Standards. Standard for Named Vegetable Oils. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization. Codex Alimentarius Commission: Rome, Italy, 1999; Adopted in 1999, Revised in 2001, 2003, 2009, 2017, 2019. Amended in 2005, 2011, 2013, 2015, 2019, 2021, 2022, 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/tr/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCXS%2B210-1999%252FCXS_210e.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Popov, A.; Ilinov, P. Chemistry of Lipids; Science and Art: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, D.R.; Farr, W.E.; Wan, P.J. Introduction to Fats and Oils Technology, 2nd ed.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.W.; Smith, B.M.; Washnock, C.S. Cardiovascular and renal benefits of dry bean and soybean intake. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 464S–474S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Madrera, R.; Campa Negrillo, A.; Ferreira Fernández, J.J. Fatty Acids in Dry Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.): A Contribution to Their Analysis and the Characterization of a Diversity Panel. Foods 2024, 13, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, I.; Orboi, M.D.; Simandi, M.D.; Chirilă, C.A.; Megyesi, C.I.; Rădulescu, L.; Drăghia, L.P.; Lukinich-Gruia, A.T.; Muntean, C.; Hădărugă, D.I.; et al. Fatty acid profile of Romanian’s common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) lipid fractions and their complexation ability by β-cyclodextrin. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, E0225474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Rodríguez, N.; Beltrán, S.; Jaime, I.; de Diego, S.M.; Sanz, M.T.; Carballido, J.R. Production of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid concentrates: A review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compounds | Accessions of Beans | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaseolus coccineus | Phaseolus vulgaris | |||

| A9E1245 | A9E1248 | A9E1249 | A9E1252 | |

| Protein, % | 24.4 ± 0.1 a | 28.0 ± 0.1 b | 26.6 ± 0.1 c | 31.5 ± 0.1 d |

| Available carbohydrate, % | 56.1 ± 0.7 a | 53.1 ± 1.1 b | 54.4 ± 0.5 b | 50.1 ± 1.1 c |

| Insoluble fibers, % | 2.8 ± 0.2 a | 2.8 ± 0.3 a | 2.6 ± 0.1 a | 2.6 ± 0.3 a |

| Fat, % | 1.4 ± 0.2 a | 1.0 ± 0.1 b | 0.9 ± 0.1 b | 1.0 ± 0.1 b |

| Ash, % | 4.7 ± 0.1 a | 4.2 ± 0.1 b | 3.9 ± 0.1 c | 3.9 ± 0.1 c |

| Caloric value, kJ/100 g (kcal/100 g) | 1421.7 ± 21.2 a (334.5 ± 5) | 1416.7 ± 24.2 a (333.3 ± 10.6) | 1411.2 ± 14 a (332.0 ± 3.2) | 1425.2 ± 24.2 a (335.3 ± 5.6) |

| Compounds | Accessions of Beans | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaseolus coccineus | Phaseolus vulgaris | |||

| A9E1245 | A9E1248 | A9E1249 | A9E1252 | |

| 1. Unsaponifiables | ||||

| -in oil, % | 7.5 ± 0.3 a | 9.3 ± 0.2 b | 12.0 ± 0.8 c | 9.8 ± 0.3 b |

| -in seeds, % | 0.11 ± 0.02 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 a | 0.11 ± 0.03 a | 0.09 ± 0.01 a |

| 2. Sterols | ||||

| -in unsaponifiables, % | 39.0 ± 0.1 a | 41.5 ± 2.5 a | 31.2 ± 3.0 b | 23.8 ± 2.5 c |

| -in oil, % | 3.0 ± 0.1 a | 3.9 ± 0.2 b | 3.7 ± 0.3 b | 2.5 ± 0.6 a |

| -in seeds, % | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 a |

| 3. Tocopherols | ||||

| -in oil, mg/kg | 3483 ± 25 a | 3615 ± 50 b | 3809 ± 20 c | 3554 ± 60 a |

| -in seeds, mg/kg | 48.7 ± 10.0 a | 36.2 ± 6.0 b | 34.3 ± 6.0 b | 35.5 ± 6.0 b |

| 4. Carotenoids | ||||

| -in oil, mg/kg | 1997 ± 50 a | 1664 ± 35 b | 1664 ± 30 b | 2049 ± 35 a |

| -in seeds, mg/kg | 27.9 ± 7.0 a | 16.6 ± 3.0 b | 14.9 ± 3.0 b | 20.5 ± 4.0 a, b |

| 5. Phospholipids | ||||

| -in oil, % | 11.5 ± 1.5 a | 11.9 ± 1.0 a | 19.1 ± 2.0 b | 23.1 ± 0.7 c |

| -in seeds, % | 0.16 ± 0.04 a | 0.12 ± 0.02 a | 0.17 ± 0.04 a, b | 0.23 ± 0.03 b |

| Fatty Acids, % | Accessions of Beans | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaseolus coccineus | Phaseolus vulgaris | |||

| A9E1245 | A9E1248 | A9E1249 | A9E1252 | |

| Myristic (C14:0) | 0.4 ± 0.1 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.1 a | 0.5 ± 0.1 a |

| Myristoleic (C14:1) | 0.3 ± 0.1 a | 0.6 ± 0.2 a, b | 0.6 ± 0.1 a, b | 0.8 ± 0.3 b |

| Pentadecanoic (C15:0) | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 b | 0.1 ± 0.0 b |

| Palmitic (C16:0) | 14.6 ± 0.2 a | 16.1 ± 0.1 b | 14.5 ± 0.2 a | 24.1 ± 0.3 c |

| Palmitoleic (C16:1) | 0.3 ± 0.1 a | 0.3 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.1 a | 0.7 ± 0.1 b |

| Margaric (C17:0) | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.1 a |

| Stearic (C18:0) | 2.6 ± 0.1 a | 1.6 ± 0.2 b | 1.2 ± 0.1 c | 2.0 ± 0.3 b |

| Oleic (9-C18:1) | 9.2 ± 0.2 a | 16.5 ± 0.3 b | 9.7 ± 0.4 a | 11.9 ± 0.5 c |

| Vaccenic (11-C18:1) | 4.5 ± 0.2 a | 1.2 ± 0.1 b | 1.3 ± 0.1 b | 1.8 ± 0.3 c |

| Linoleic (C18:2) | 41.4 ± 0.5 a | 15.8 ± 0.3 b | 26.2 ± 0.2 c | 17.6 ± 0.5 d |

| Linolenic (C18:3) | 26.3 ± 0.3 a | 47.2 ± 0.2 b | 45.5 ± 0.5 c | 40.2 ± 0.2 d |

| Arachidic (C20:0) | - * | 0.1 ± 0.0 | - | - |

| SFA | 18.0 ± 0.4 a | 18.4 ± 0.3 a | 16.3 ± 0.4 b | 27.0 ± 0.7 c |

| UFA | 82.0 ± 1.4 a | 81.6 ± 1.1 a | 83.7 ± 1.4 a | 73.0 ± 1.9 b |

| MUFA | 14.3 ± 0.6 a | 18.6 ± 0.6 b | 12.0 ± 0.7 c | 15.2 ± 1.2 a |

| PUFA | 67.7 ± 0.8 a | 63.0 ± 0.5 b | 71.7 ± 0.7 c | 57.8 ± 0.7 d |

| Iodine value, g I2/100 g | 155 ± 2 a | 173 ± 1 b | 181 ± 2 c | 153 ± 2 a |

| Sterols, % | Accessions of Beans | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaseolus coccineus | Phaseolus vulgaris | |||

| A9E1245 | A9E1248 | A9E1249 | A9E1252 | |

| Cholesterol | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.3 ± 0.1 a | 0.3 ± 0.1 a | 0.3 ± 0.1 a |

| Brassicasterol | 1.5 ± 0.1 a | 2.4 ± 0.2 b | 1.9 ± 0.1 c | 2.0 ± 0.2 c |

| Campesterol | 3.5 ± 0.2 a | 5.8 ± 0.3 b | 6.2 ± 0.3 b | 5.1 ± 0.1 c |

| Stigmasterol | 31.8 ± 0.3 a | 36.9 ± 0.2 b | 34.0 ± 0.4 c | 35.3 ± 0.3 d |

| Δ7-Campesterol | 2.4 ± 0.1 a | 2.3 ± 0.1 a, b | 2.0 ± 0.2 a, b | 2.1 ± 0.1 b |

| β-Sitosterol | 59.1 ± 0.2 a | 47.3 ± 0.3 b | 51.2 ± 0.3 c | 52.0 ± 0.4 d |

| Δ5-Avenasterol | 0.8 ± 0.1 a | 4.4 ± 0.2 b | 2.8 ± 0.1 c | 1.6 ± 0.2 d |

| Δ7-Stigmasterol | 0.5 ± 0.1 a | 0.4 ± 0.0 a | 1.2 ± 0.2 b | 1.3 ± 0.1 b |

| Δ7-Avenasterol | 0.2 ± 0.1 a, b | 0.2 ± 0.0 a | 0.4 ± 0.1 b | 0.3 ± 0.1 a, b |

| Tocopherols, % | Accessions of Beans | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phaseolus coccineus | Phaseolus vulgaris | |||

| A9E1245 | A9E1248 | A9E1249 | A9E1252 | |

| α-tocopherol | 1.0 ± 0.2 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 a | 0.5 ± 0.1 b | 1.5 ± 0.2 c |

| β-tocotrienol | 1.0 ± 0.1 | - * | - | - |

| γ-tocopherol | 93.1 ± 0.1 a | 91.0 ± 0.4 b | 95.0 ± 0.2 c | 88.2 ± 0.3 d |

| γ-tocotrienol | 1.2 ± 0.1 a | 4.4 ± 0.2 b | 1.5 ± 0.3 a | 7.2 ± 0.5 c |

| δ-tocopherol | 3.7 ± 0.2 a | 3.8 ± 0.1 a | 3.0 ± 0.2 b | 3.1 ± 0.1 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Antova, G.; Stoilova, T.; Chavdarov, P. Nutritional Value and Bioactive Lipid Constituents in Seeds of Phaseolus Bean Cultivated in Bulgaria. AppliedChem 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010004

Antova G, Stoilova T, Chavdarov P. Nutritional Value and Bioactive Lipid Constituents in Seeds of Phaseolus Bean Cultivated in Bulgaria. AppliedChem. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntova, Ginka, Tsvetelina Stoilova, and Petar Chavdarov. 2026. "Nutritional Value and Bioactive Lipid Constituents in Seeds of Phaseolus Bean Cultivated in Bulgaria" AppliedChem 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010004

APA StyleAntova, G., Stoilova, T., & Chavdarov, P. (2026). Nutritional Value and Bioactive Lipid Constituents in Seeds of Phaseolus Bean Cultivated in Bulgaria. AppliedChem, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010004