Metabolomic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Methanolic Extracts of Mentha pulegium L. and Lavandula stoechas L. from the Portuguese Flora

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

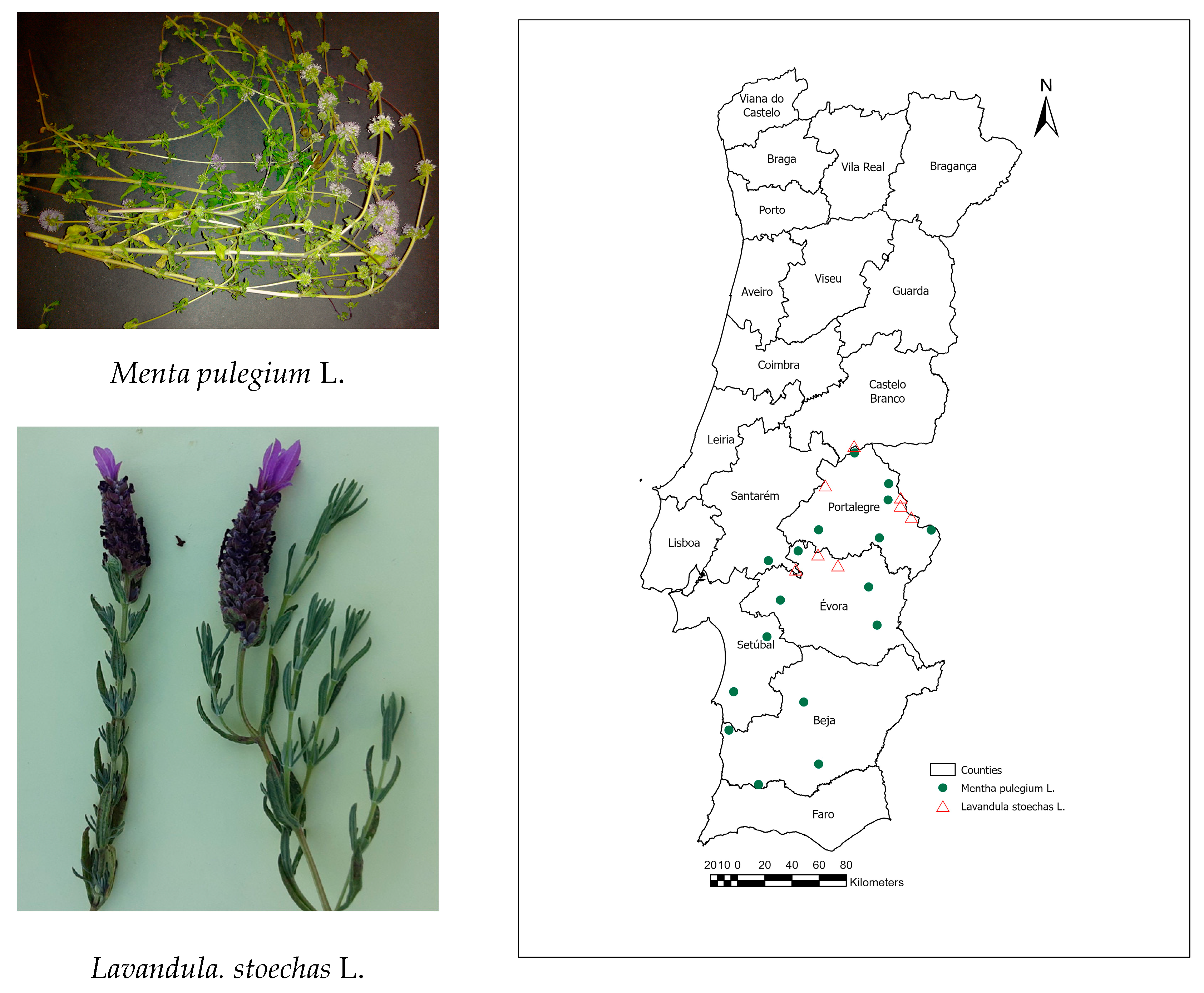

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

2.3. Preparation of Plant Extracts

2.4. Total Phenolic Content by Folin–Ciocalteu Method

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.5.1. Ferric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Power Assay

2.5.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity Assay

2.6. Determination of Phenolic Compounds in Pennyroyal and Lavender Extracts by HRMS

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Yield of Phenolic Compounds Extraction

3.1.1. Pennyroyal

3.1.2. French Lavender

3.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) and Antioxidant Capacity

3.2.1. Pennyroyal

3.2.2. French Lavender

3.3. Identification of Phytochemicals in Mentha pulegium L. and Lavandula stoechas by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry

3.3.1. Pennyroyal

3.3.2. French Lavender

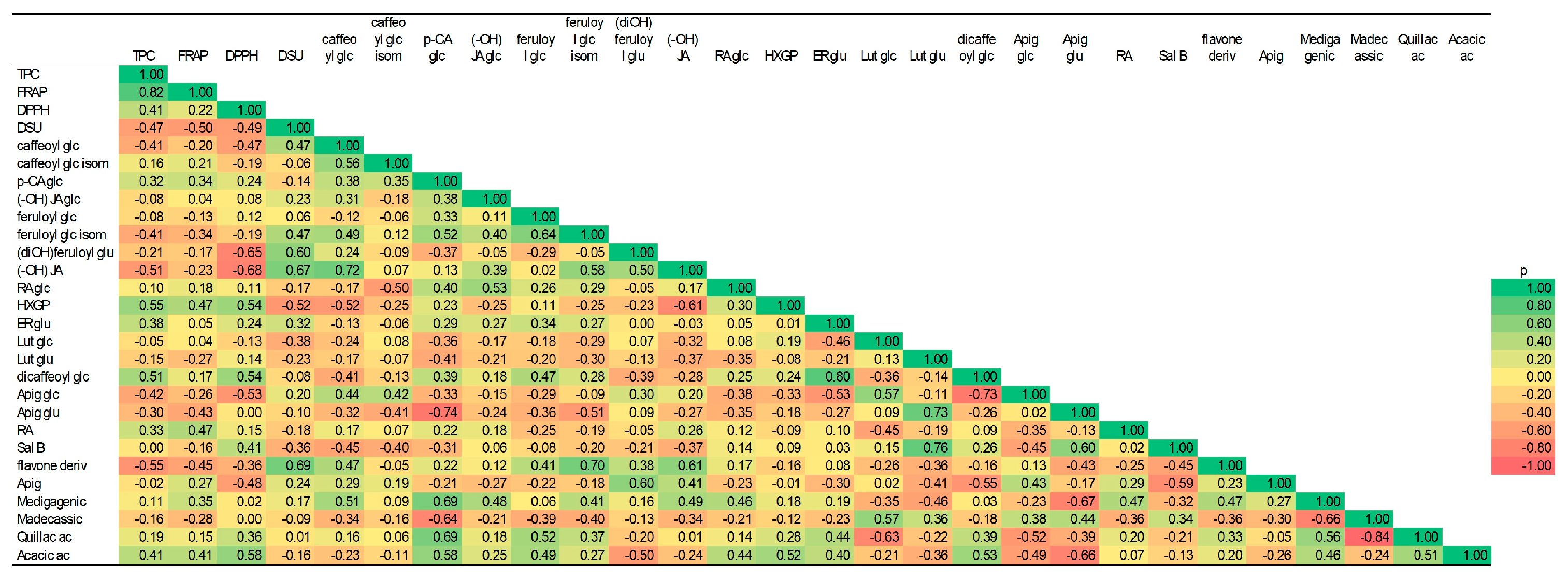

3.4. Correlations Among Different Parameters

3.4.1. Pennyroyal

3.4.2. French Lavender

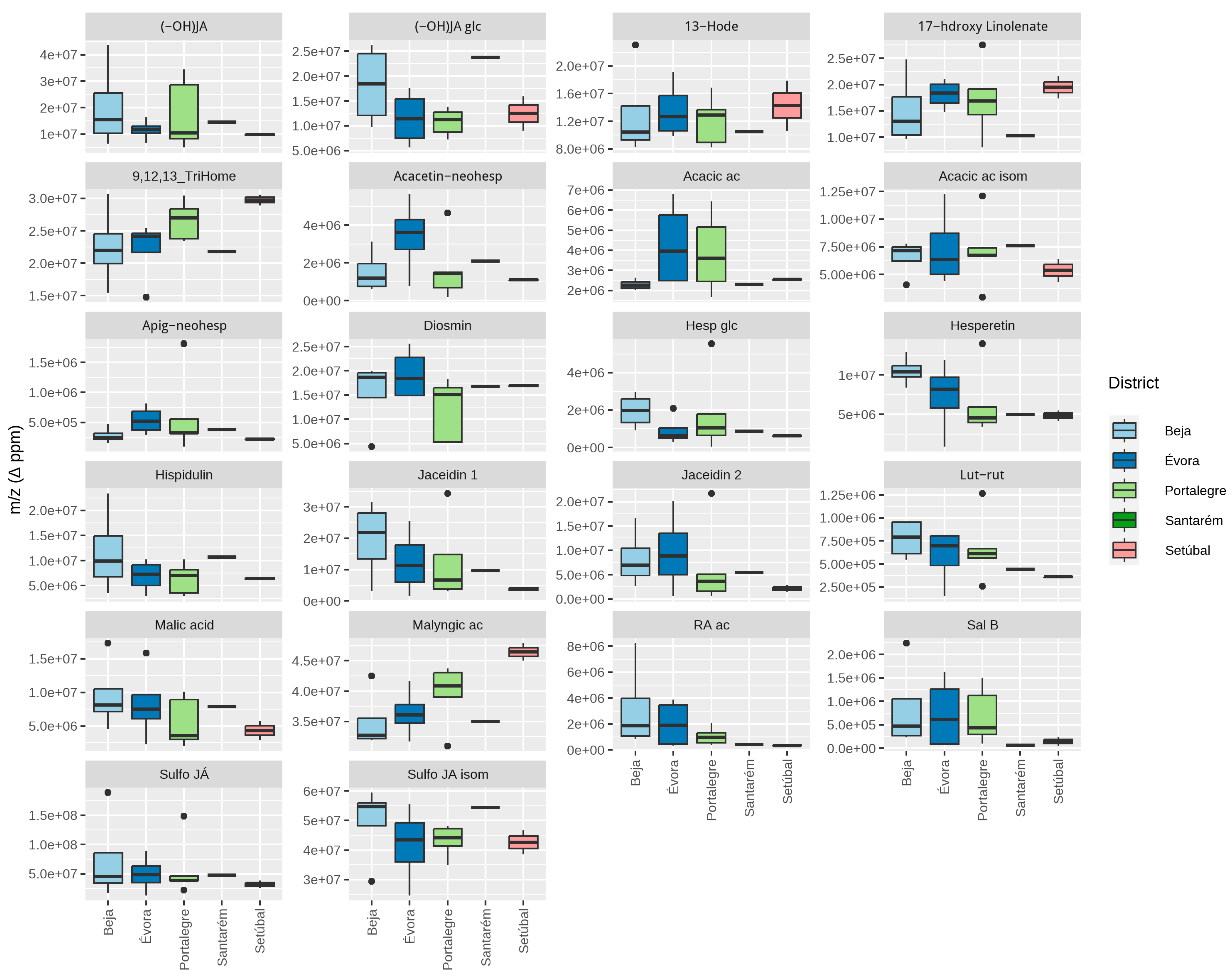

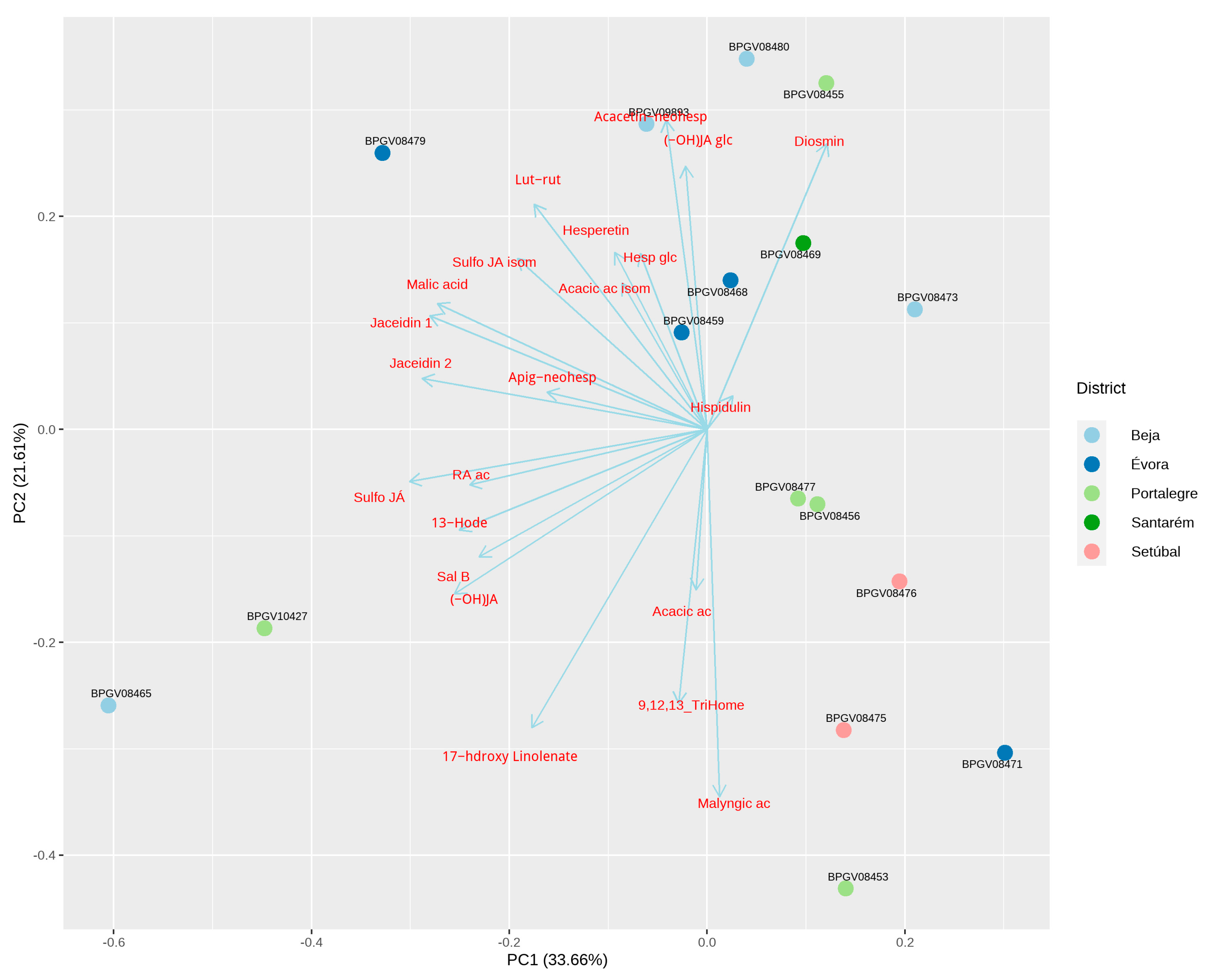

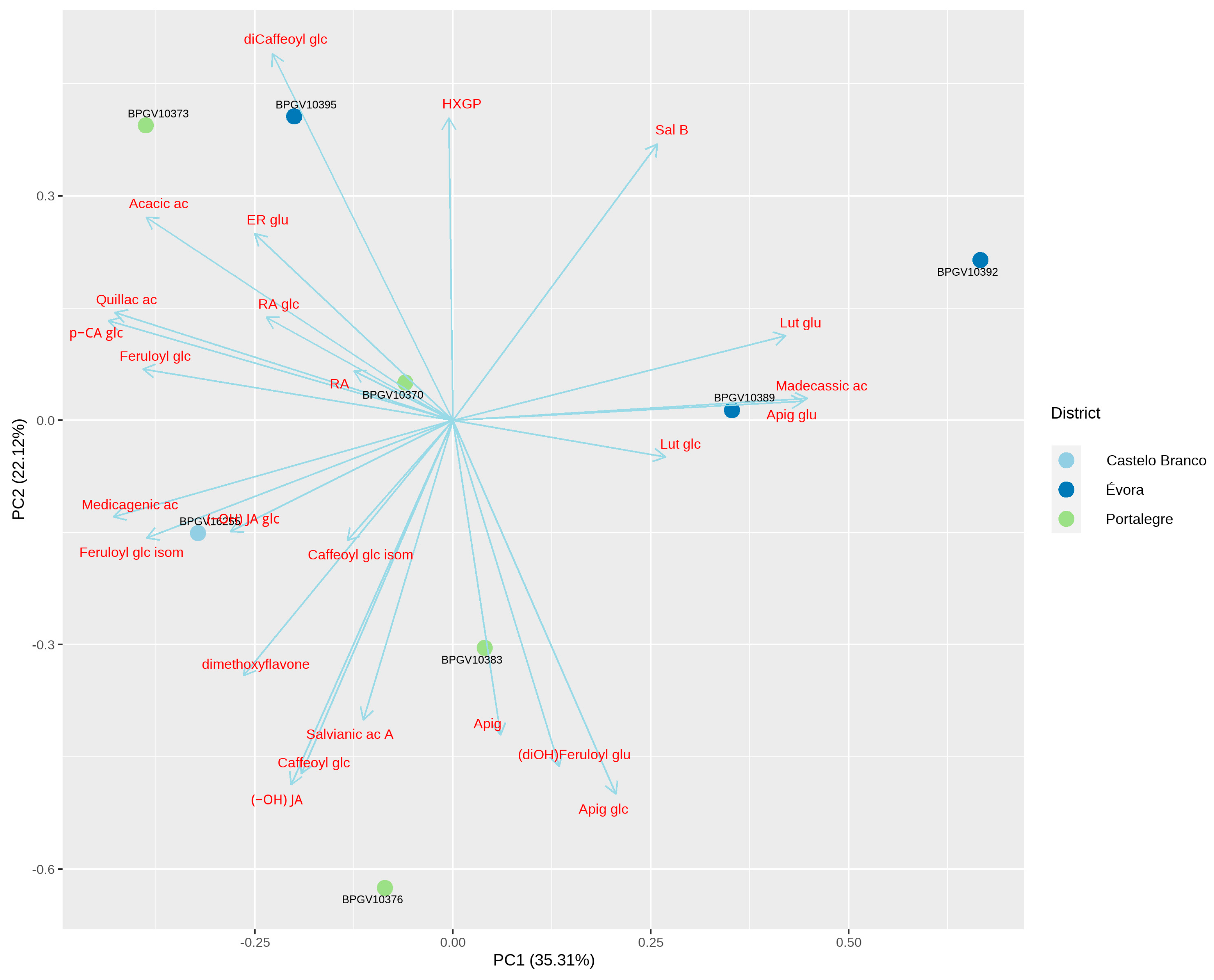

3.5. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to Assess Overall Variation

3.5.1. Pennyroyal

3.5.2. French Lavender

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stankovic, M. Lamiaceae Species Biology, Ecology and Practical Uses; Special Issue Published in Plants; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Domingues, J.; Delgado, F.; Gonçalves, J.C.; Zuzarte, M.; Duarte, A.P. Mediterranean Lavenders from Section Stoechas: An Undervalued Source of Secondary Metabolites with Pharmacological Potential. Metabolites 2023, 13, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khennouf, S.; Dalila, B.; Djidel, S.; Dahamna, S.; Amira, S.; Noureddine, C.; Baghiani, A.; Harzallah, D.; Arrar, L. Polyphenols and antioxidant properties of extracts from Mentha pulegium L. and Matricaria chamomilla L. Pharmacogn. Commun. 2013, 3, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taamalli, A.; Arráez-Román, D.; Abaza, L.; Iswaldi, I.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Zarrouk, M.; Segura-Carretero, A. LC-MS-based metabolite profiling of methanolic extracts from the medicinal and aromatic species Mentha pulegium and Origanum majorana. Phytochem. Anal. 2015, 26, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim Nalkiran, H.; Nalkiran, I. Anticancer Effects and Phytochemical Profile of Lavandula stoechas. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćavar Zeljković, S.; Šišková, J.; Komzáková, K.; De Diego, N.; Kaffková, K.; Tarkowski, P. Phenolic Compounds and Biological Activity of Selected Mentha Species. Plants 2021, 10, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrherabi, A.; Abdnim, R.; Loukili, E.H.; Laftouhi, A.; Lafdil, F.Z.; Bouhrim, M.; Mothana, R.A.; Noman, O.M.; Eto, B.; Ziyyat, A.; et al. Antidiabetic potential of Lavandula stoechas aqueous extract: Insights into pancreatic lipase inhibition, antioxidant activity, antiglycation at multiple stages and anti-inflammatory effects. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1443311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politeo, O.; Bektašević, M.; Carev, I.; Jurin, M.; Roje, M. Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant Potential and Cholinesterase Inhibition Potential of Extracts from Mentha pulegium L. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1800374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, B.; Marques, A.; Ramos, C.; Batista, I.; Serrano, C.; Matos, O.; Neng, N.R.; Nogueira, J.M.F.; Saraiva, J.A.; Nunes, M.L. European pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium) from Portugal: Chemical composition of essential oil and antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of extracts and essential oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 36, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, F.; Lounis, N.; Mebarakou, S.; Guendouze, N.; Yalaoui-Guellal, D.; Madani, K.; Boulekbache-Makhlouf, L.; Duez, P. Impact of Growth Sites on the Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Activities of Three Algerian Mentha Species (M. pulegium L., M. rotundifolia (L.) Huds., and M. spicata L.). Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 886337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, V.R.; Barata, A.M.; Rocha, F.; Pedro, L.G.; Barroso, J.G.; Figueiredo, A.C.L. Morphological and chemical variability assessment from Portuguese Mentha pulegium L. (pennyroyal) accessions. In Proceedings of the VIII International Ethnobotany Symposium, Lisbon, Portugal, 3-8 October 2010; Friends, the University for Peace Foundation and Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lisbon: Lisbon, Portugal. ISBN 978-989-20-2789-0. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brahmi, F.; Dahmoune, F.; Kadri, N.; Chibane, M.; Dairi, S.; Remini, H.; Oukmanou-Bensidhoum, S.; Mouni, L.; Madani, K. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of two Algerian Mentha species M. rotundifolia (L.) Huds, M. pulegium L., extracted with different solvents. J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2017, 14, 20160064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornara, L.; Sgrò, F.; Raimondo, F.M.; Ingegneri, M.; Mastracci, L.; D’Angelo, V.; Germanò, M.P.; Trombetta, D.; Smeriglio, A. Pedoclimatic Conditions Influence the Morphological, Phytochemical and Biological Features of Mentha pulegium L. Plants 2023, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafrihi, M.; Imran, M.; Tufail, T.; Gondal, T.A.; Caruso, G.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, R.; Atanassova, M.; Atanassov, L.; Valere Tsouh Fokou, P.; et al. The Wonderful Activities of the Genus Mentha: Not Only Antioxidant Properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, V.; Barata, A. Ex situ morphological assessment of wild lavandula populations in portugal. Open Access J. Med. Aromat. Plants 2017, V3, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A.C.; Pedro, L.G.; Barroso, J.G.; Trindade, H.; Sanches, J.; Oliveira, C.; Correia, M. Mentha pulegium L. Agrotec Fevereiro 2014, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.; Fazal, H.; Ahmad, I.; Abbasi, B.H. Free radical scavenging (DPPH) potential in nine Mentha species. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2011, 28, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebali, J.; Ghazghazi, H.; Aouadhi, C.; Elbini-Dhouib, I.; Ben Salem, R.; Srairi-Abid, N.; Marrakchi, N.; Rigane, G. Tunisian Native Mentha pulegium L. Extracts: Phytochemical Composition and Biological Activities. Molecules 2022, 27, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, Ì.; Güngör Şat, İ.; Beydemir, Ş.; Elmastaş, M.; İrfan Küfrevioǧlu, Ö. Comparison of antioxidant activity of clove (Eugenia caryophylata Thunb) buds and lavender (Lavandula stoechas L.). Food Chem. 2004, 87, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, M.d.M.; Algieri, F.; Rodriguez-Nogales, A.; Gálvez, J.; Segura-Carretero, A. Phytochemical profiling of anti-inflammatory Lavandula extracts via RP–HPLC–DAD–QTOF–MS and –MS/MS: Assessment of their qualitative and quantitative differences. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamad, R.; Kumar, S.; Akhtar, M.; Aqil, M.; Yar, M.S.; Akram, M.; Ismail, M.V.; Mujeeb, M. A Comprehensive Review of Lavandula stoechas L. (Ustukhuddus) Plant: Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and In Silico Studies. Chem. Biodivers 2025, 22, e202401996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğru, Z.; Doğru, M.S.; Yeşilay, G.; Kayalar, Ö.; Elmastaş, M. Anticancer activity of Lavandula stoechas L. flower ethanolic extract through apoptotic pathway modulation in colorectal cancer cells. Acta Pharm 2025, 75, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ez zoubi, Y.; Bousta, D.; Farah, A. A Phytopharmacological review of a Mediterranean plant: Lavandula stoechas L. Clin. Phytoscience 2020, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.N.; Cadavez, V.; Caleja, C.; Pereira, E.; Calhelha, R.C.; Molina, A.K.; Finimundy, T.; Kostić, M.; Soković, M.; Teixeira, J.A.; et al. Chemical profiles and bioactivities of polyphenolic extracts of Lavandula stoechas L., Artemisia dracunculus L. and Ocimum basilicum L. Food Chem 2024, 451, 139308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddouchi, F.; Chaouche, T.M.; Saker, M.; Ghellai, I.; Boudjemai, O. Phytochemical screening, phenolic content and antioxidant activity of Lavandula species extracts from Algeria. J. Pharm. Istanb. Univ. 2021, 51, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, A.; Anwar, R.; Ahmad, M. Lavandula stoechas (L) a Very Potent Antioxidant Attenuates Dementia in Scopolamine Induced Memory Deficit Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, Y.; Usta, K.; Usta, A.; Maltas Cagil, E.; Yildiz, S. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity, Phytochemicals and ESR Analysis of Lavandula stoechas. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2015, 128, B-483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celep, E.; Akyüz, S.; İnan, Y.; Yesilada, E. Assessment of potential bioavailability of major phenolic compounds in Lavandula stoechas L. ssp. stoechas. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 118, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesage-Meessen, L.; Bou, M.; Ginies, C.; Chevret, D.; Navarro, D.; Drula, E.; Bonnin, E.; del Río, J.; Odinot, E.; Bisotto, A.; et al. Lavender- and lavandin-distilled straws: An untapped feedstock with great potential for the production of high-added value compounds and fungal enzymes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriti, J.; Fares, N.; Msaada, K.; Zarroug, Y.; Boulares, M.; Djebbi, S.; Selmi, S.; Limam, F. Phenological stage effect on phe-nolic composition, antioxidant, and antibacterialy activity of Lavandula stoechas extract. La Riv. Ital. Delle Sostanze Grasse 2022, 99, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Apak, R.; Özyürek, M.; Güçlü, K.; Çapanoğlu, E. Antioxidant Activity/Capacity Measurement. 1. Classification, Physicochemical Principles, Mechanisms, and Electron Transfer (ET)-Based Assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 997–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, E.J.; Kellogg, J.J. Chemometric-Guided Approaches for Profiling and Authenticating Botanical Materials. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 780228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagbogu, C.F.; Zhou, J.; Olasupo, F.O.; Baba Nitsa, M.; Beckles, D.M. Lipidomic and metabolomic profiles of Coffea canephora L. beans cultivated in Southwestern Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0234758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, F.; Serra, O.; Vaz, M.; Silva, I.; Gaspar, C.; Lopes, V.; Barata, A.M. Portugal Gene Bank. In Plant Gene Banks: Genetic Resources Collections, Conservation and Sustainable Utilization; Al-Khayri, J.M., Salem, K.F.M., Jain, S.M., Kourda, H.C., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Slinkard, K.; Singleton, V.L. Total Phenol Analysis: Automation and Comparison with Manual Methods. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1977, 28, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.; Oliveira, M.C.; Lopes, V.R.; Soares, A.; Molina, A.K.; Paschoalinotto, B.H.; Pires, T.C.S.P.; Serra, O.; Barata, A.M. Chemical Profile and Biological Activities of Brassica rapa and Brassica napus Ex Situ Collection from Portugal. Foods 2024, 13, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deighton, N.; Brennan, R.; Finn, C.; Davies, H. Antioxidant properties of domesticated and wildRubus species. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, S.; Tsuda, K.; Muto, N.; Nakatani, S. Changes in Antioxidant Activity during Fruit Development in Citrus Fruit. Hortic. Res. 2002, 1, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StatSoft. Inc. STATISTICA, Version 12; StatSoft. Inc.: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2013.

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A. metan: An R package for multi-environment trial analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N.; Sriti, J.; Bachrouch, O.; Msaada, K.; Khammassi, S.; Majdi, H.; Selmi, S.; Boushih, E.; Ouertani, M.; Hachani, N.; et al. Phenological stage effect on phenolic composition and repellent potential of Mentha pulegium against Tribolium castaneum and Lasioderma serricorne. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2018, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayarani-Najaran, Z.; Hadipour, E.; Seyed Mousavi, S.M.; Emami, S.A.; Mohtashami, L.; Javadi, B. Protective effects of Lavandula stoechas L. methanol extract against 6-OHDA-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 273, 114023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apak, R.; Güçlü, K.; Özyürek, M.; Çelik, S.E. Mechanism of antioxidant capacity assays and the CUPRAC (cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity) assay. Microchim. Acta 2008, 160, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Zhong, Y. Measurement of antioxidant activity. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 18, 757–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, R.L.; Wu, X.; Schaich, K. Standardized methods for the determination of antioxidant capacity and phenolics in foods and dietary supplements. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4290–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajimehdipoor, H.; Gohari, A.R.; Ajani, Y.; Saeidnia, S. Comparative study of the total phenol content and antioxidant activity of some medicinal herbal extracts. Res. J. Pharmacogn. 2014, 1, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ulewicz-Magulska, B.; Wesolowski, M. Antioxidant Activity of Medicinal Herbs and Spices from Plants of the Lamiaceae, Apiaceae and Asteraceae Families: Chemometric Interpretation of the Data. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Lamiaceae often used in Portuguese folk medicine as a source of powerful antioxidants: Vitamins and phenolics. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrovankova, S.; Mlcek, J. Antioxidant Potential and Its Changes Caused by Various Factors in Lesser-Known Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, G.; Yagi, S.; Selvi, S.; Cziáky, Z.; Jeko, J.; Sinan, K.I.; Topcu, A.A.; Erci, F.; Boczkaj, G. Elucidation of chemical compounds in different extracts of two Lavandula taxa and their biological potentials: Walking with versatile agents on the road from nature to functional applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 204, 117366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascoloti Spréa, R.; Caleja, C.; Pinela, J.; Finimundy, T.C.; Calhelha, R.C.; Kostić, M.; Sokovic, M.; Prieto, M.A.; Pereira, E.; Amaral, J.S.; et al. Comparative study on the phenolic composition and in vitro bioactivity of medicinal and aromatic plants from the Lamiaceae family. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, F.; Rahimi, K.; Ahmadi, A.; Hooshmandi, Z.; Amini, S.; Mohammadi, A. Anti-inflammatory effects of Mentha pulegium L. extract on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells are mediated by TLR-4 and NF-κB suppression. Heliyon 2024, 10, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebai, E.; Serairi, R.; Saratsi, K.; Abidi, A.; Sendi, N.; Darghouth, M.A.; Wilson, M.S.; Sotiraki, S.; Akkari, H. Hydro-Ethanolic Extract of Mentha pulegium Exhibit Anthelmintic and Antioxidant Proprieties In Vitro and In Vivo. Acta Parasitol. 2020, 65, 375–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbal, A.; Aytar, E.C.; Aydoğmuş, Z.; Fenghour, M.; Gheddar, K. Comprehensive evaluation of the anti-inflammatory effects of Lavandula stoechas L.: In vivo, in vitro, and in silico studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 357, 120887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baali, F.; Boumerfeg, S.; Boudjelal, A.; Denaro, M.; Ginestra, G.; Baghiani, A.; Righi, N.; Deghima, A.; Benbacha, F.; Smeriglio, A.; et al. Wound-healing activity of Algerian Lavandula stoechas and Mentha pulegium extracts: From traditional use to scientific validation. Plant Biosyst.-Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2022, 156, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferehan, H.; Laaradia, M.A.; Oufquir, S.; Aboufatima, R.; Moubtakir, S.; Sokar, Z.; Chait, A.; Bagri, A. Antioxidant, Analgesic and Anti-inflammatory Effects of Ethanolic Extract of Moroccan Lavandula stoechas L. OnLine J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 21, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, T. Metabolic profile and biological activities of Lavandula stoechas L. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2018, 64, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, N.; Santiago, A.; Alías, J.C. Quantification of the Antioxidant Activity of Plant Extracts: Analysis of Sensitivity and Hierarchization Based on the Method Used. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.; Papp, V.A.; Pál, A.; Prokisch, J.; Mirani, S.; Toth, B.E.; Alshaal, T. Comparative Study on Antioxidant Capacity of Diverse Food Matrices: Applicability, Suitability and Inter-Correlation of Multiple Assays to Assess Polyphenol and Antioxidant Status. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pennyroyal | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Accession | Geography | Elevation (m) | Lat. N; Long. W |

| BPGV08453 | Portalegre | 238 | 39°5′8.88″ N; 7°1′51.96″ W |

| BPGV08454 | Portalegre | 607 | 39°17′20.76″ N; 7°23′51.72″ W |

| BPGV08455 | Portalegre | 644 | 39°23′51″ N; 7°23′22.92″ W |

| BPGV08456 | Portalegre | 241 | 39°2′11.76″ N; 7°28′22.8″ W |

| BPGV08459 | Évora | 358 | 38°42′45.72″ N; 7°34′3.72″ W |

| BPGV08465 | Beja | 201 | 37°57′0″ N; 8°6′59.76″ W |

| BPGV08468 | Évora | 57 | 38°57′9″ N; 8°9′49.68″ W |

| BPGV08469 | Santarém | 138 | 38°53′13.92″ N; 8°25′3.72″ W |

| BPGV08471 | Évora | 225 | 38°37′36.84″ N; 8°18′50.76″ W |

| BPGV08473 | Beja | 88 | 37°45′48.96″ N; 8°44′35.88″ W |

| BPGV08476 | Setúbal | 63 | 38°23′1.68″ N; 8°25′37.92″ W |

| BPGV08477 | Portalegre | 231 | 39°36′5.76″ N; 7°40′50.88″ W |

| BPGV08479 | Évora | 265 | 38°27′36.72″ N; 7°29′49.92″ W |

| BPGV08480 | Beja | 184 | 37°24′12.96″ N; 8°29′35.88″ W |

| BPGV09893 | Beja | 217 | 37°32′24.72″ N; 7°59′33.72″ W |

| BPGV10427 | Portalegre | 175 | 39°5′31.2″ N; 7°59′24″ W |

| BPGV08475 | Setúbal | 105 | 38°1′3.72″ N; 8°42′16.992″ W |

| French Lavender | |||

| Accession | Geography | Elevation (m) | Lat. N; Long. W |

| BPGV10370 | Portalegre | 325 | 39°10′19.2″ N; 7°12′0″ W |

| BPGV10373 | Portalegre | 508 | 39°14′56.4″ N; 7°17′24″ W |

| BPGV10376 | Portalegre | 528 | 39°18′10.8″ N; 7°17′16.8″ W |

| BPGV10383 | Portalegre | 246 | 39°23′16.8″ N; 7°55′51.6″ W |

| BPGV10389 | Évora | 180 | 38°55′48″ N; 7°59′42″ W |

| BPGV10392 | Évora | 132 | 38°49′48″ N; 8°11′2.4″ W |

| BPGV10395 | Évora | 250 | 38°51′25.2″ N; 7°49′33.6″ W |

| BPGV16255 | Castelo Branco | 212 | 39°38′56.4″ N; 7°41′2.4″ W |

| Accession | Origin | Yield % | TPC mg GAE/g DW | FRAP μmol Fe2+/g DW | DPPH μmol TE/g DW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPGV08471 | Évora | 11.659 ± 0.023 a,b,c,d,e,f | 28.81 ± 2.11 b,c,d,e | 193.561 ± 0.142 a,b,c,d,e | 73.371 ± 3.676 a,b,c |

| BPGV08475 | Setúbal | 10.148 ± 0.893 a,b,c | 27.77 ± 4.63 a,b,c,d,e | 239.243 ± 3.146 f,g | 288.144 ± 7.930 a,b,c |

| BPGV08480 | Beja | 12.860 ± 0.318 d,e,f | 30.88 ± 7.60 b,c,d,e | 242.814 ± 4.961 f,g | 76.404 ± 3.170 b,c |

| BPGV08459 | Évora | 9.392 ± 0.167 a | 24.89 ± 0.29 a,b,c | 181.025 ± 7.559 a,b,c | 252.614 ± 8.368 c |

| BPGV08479 | Évora | 13.235 ± 0.498 e,f | 34.03 ± 5.70 d,e | 228.745 ± 1.548 d,e,f,g | 58.935 ± 3.695 a |

| BPGV08476 | Setúbal | 13.041 ± 0.334 d,e,f | 20.07 ± 5.90 a | 170.503 ± 2.835 a | 58.784 ± 2.054 a |

| BPGV09893 | Beja | 12.087 ± 0.289 b,c,d,e,f | 31.76 ± 10.20 c,d,e | 289.680 ± 3.013 h | 146.738 ± 4.789 b,c |

| BPGV08477 | Portalegre | 12.126 ± 0.866 b,c,d,d,e,f | 27.87 ± 0.07 a,b,c,d,e | 188.134 ± 5.336 a,b,c,d | 63.139 ± 0.859 b,c |

| BPGV08473 | Beja | 10.467 ± 0.198 a,b,c,d | 29.22 ± 0.07 b,c,d,e | 225.338 ± 6.580 c,d,e,f,g | 200.126 ± 9.584 a,b,c |

| BPGV08454 | Portalegre | 10.802 ± 0.404 a,b,c,d,e | 22.59 ± 0.02 a,b | 237.167 ± 0.712 e,f,g | 84.396 ± 8.424 b,c |

| BPGV08455 | Portalegre | 12.546 ± 0.649 c,d,e,f | 30.84 ± 2.46 b,c,d,e | 237.017 ± 4.491 e,f,g | 78.416 ± 8.258 a,b.c |

| BPGV08468 | Évora | 13.858 ± 0.464 f | 28.97 ± 5.43 b,c,d,e | 229.171 ± 1.139 d,e,f,g | 69.518 ± 8.713 a,b,c |

| BPGV08469 | Santarém | 12.106 ± 0.260 b,c,d,e,f | 28.69 ± 6.91 b,c,d,e | 221.759 ± 1.389 b,c,d,e,f,g | 57.505 ± 4.497 a |

| BPGV08456 | Portalegre | 11.892 ± 0.269 a,b,c,d,e,f | 35.29 ± 2.35 e | 224.637 ± 1.092 c,d,e,f,g | 67.375 ± 5.567 a,b,c |

| BPGV10427 | Portalegre | 10.048 ± 1.813 a,b,c | 29.01 ± 2.64 b,c,d,e | 179.244 ± 2.921 a,b | 286.509 ± 12.834 a,b,c |

| BPGV08465 | Beja | 12.537 ± 0.377 c,d,e,f | 35.29 ± 1.06 e | 265.936 ± 0.223 g,h | 67.204 ± 0.422 a |

| BPGV08453 | Portalegre | 9.809 ± 0.897 a,b | 25.58 ± 1.78 a,b,c,d | 199.841 ± 2.973 a,b,c,d,e,f | 356.246 ± 3.477 a,b,c |

| Accession | Origin | Yield % | TPC mg GAE/g DW | FRAP μmol Fe2+/g DW | DPPH μmol TE/g DW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPGV10370 | Portalegre | 30.130 ± 2.503 a | 58.654 ± 6.719 a | 141.812 ± 4.969 a,b | 175.274 ± 4.383 a |

| BPGV10373 | Portalegre | 24.020 ± 2.263 a,b | 64.694 ± 4.193 a | 135.530 ± 3.782 a | 178.912 ± 0.666 a |

| BPGV10376 | Portalegre | 26.452 ± 1.222 a | 42.133 ± 3.037 b | 102.215 ± 2.012 c | 170.3042 ± 2.662 a |

| BPGV10383 | Portalegre | 17.104 ± 1.663 b | 62.473 ± 1.788 a | 153.046 ± 2.871 b | 174.015 ± 4.277 a |

| BPGV10389 | Évora | 26.882 ± 1.270 a | 61.422 ± 0.703 a | 148.661 ± 0.076 a,b | 175.259 ± 0.409 a |

| BPGV10392 | Évora | 22.764 ± 0.634 a,b | 52.226 ± 0.520 a,b | 110.034 ± 5.741 c | 177.099 ± 0.496 a |

| BPGV10395 | Évora | 26.270 ± 3.403 a | 62.279 ± 1.796 a | 143.756 ± 2.827 a,b | 179.355 ± 2.689 a |

| BPGV16255 | Castelo Branco | 24.444 ± 0.238 a,b | 54.686 ± 4.007 a,b | 136.678 ± 2.686 a | 174.847 ± 0.304 a |

| Peak | tR (min) | Ionic Formula | [M-H]− [(m/z)(Δ ppm; mSigma] | MS/MS [(m/z)(Δ ppm) (Attribution)] | Proposed Metabolite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 3.33 | [C12H17O7S]− | 305.0712 (−0.7; 9.5) | 225.1144 [C12H17O4)− (−5.4)] | Sulfo jasmonate |

| P2 | 3.48 | [C18H27O9]− | 387.1676 (−3.9; 11.8) | 299.1502 [(C15H23O6)− (−2.8)] 251.0568 [(C12H11O6)− (−2.8)] 207.1038 [(C12H15O3)− (−2.8)] 179.0347 [(C9H7O4)− (−0.1)] 161.0243 [(C9H5O3)− (−0.7)] | Hidroxyjasmonic acid Glc |

| P3 | 3.54 | [C12H17O7S]− | 305.0715 (−4.6; 12.5) | 225.1145 [C12H17O4)− (−5.8)] 147.0826 [C10H11O1)− (−6.9)] | Sulfo jasmonate isomer |

| P4 | 3.85 | [C12H17O4]− | 225.1140 (−3.6; 3.5) | 167.1083 [C10H15O2)− (−3.5)] 147.0816 [C10H11O1)− (−2.9)] | Hydroxyjasmonic acid |

| P5 | 3.91 | [C27H29O15]− | 593.1541 (−4.1; 10.4) | 447.0960 [C21H19O11)− (−6.0)] 327.0533 [C17H11O7)− (−7.1) 0, 2X0−] 285.0422 [C15H9O6)− (−6.0) Y0−] 284.0340 [C15H8O6)− (−4.9) (Y0−H)−●] | Luteolin-7-O-rutinoside |

| P6 | 4.14 | [C27H29O14]− | 577.1580 (−3.1; 21.1] | 269.0467 [C15H9O5)− (−4.4) Y0−] | Apigenin-7-O-neohesperidoside |

| P7 | 4.22 | [C28H31O15]− | 607.1693 (−3.5; 12.1] | 299.0581 [C16H11O6)− (−3.1) Y0−] | Diosmin |

| P8 | 4.26 | [C28H33O15]− | 609.1852 (−4.4; 14.5] | 301.0737 [C16H13O6)− (−5.2) Y0−] | Hesperidin |

| P9 | 4.35 | [C18H15O8]− | 359.0787(−4.0; 14.2) | 197.0460 [C9H9O5)− (−2.2)] 179.0349 [C9H7O4)− (−2.2)] 161.0242 [C9H5O3)− (−1.2)] 135.0450 [C8H7O2)− (−1.2)] | Rosmarinic acid |

| P10 | 4.43 | [C22H23O11]− | 463.1259 (−2.9; 12.9) | 301.0731 [C16H13O6)− (−4.5) Y0−] 268.0388 [C15H8O5)− (−3.9)] | Hesperitin-7-O-Glc |

| P11 | 4.45 | [C36H29O16]− | 717.1481(−3.1; 6.8) | 519.0960 [C27H19O11)− (−3.9)] 475.1058 [C26H9O9)− (−4.8)] 339.0525 [C18H11O7)− (−0.5)] 299.0577 [C16H11O6)− (−2.8)] | Salvianolic acid B |

| P12 | 4.72 | [C28H31O14]− | 591.1727 (−1.4; 13.2) | 283.0606 [C16H11O5)− (−2.1) Y0−] 268.0388 [C15H8O5)−● (−3.9)] | Acacetin-7-O-rutinoside |

| P13 | 4.76 | [C28H33O14]− | 593.1889 (−2.2; 8.7) | 342.1477 [C20H22O6)− (−1.4)] 285.0787 [C16H13O5)− (−6.1) Y0−] | isoSakuranetin-7-O-rutinoside |

| P14 | 5.32 | [C18H31O5]− | 327.2188 (−3.4; 6.1) | 291.1976 [C18H27O3)− (−3.5)] 229.1455 [C12H21O4)− (−4.2)] 211.1347 [C12H19O3)− (−3.4)] 171.1027 [C9H15O3)− (−0.4)] | Malyngic acid |

| P15 | 5.40 | [C16H11O6]− | 299.0564 (−4.1; 32.7) | 284.0336 [C15H8O6)−● (−3.5)] 283.0232 [C15H7O6)− (−1.9)] 256.0383 [C14H8O5)− (−1.9)] | Diosmetin |

| P16 | 5.42 | [C18H15O8]− | 359.0781 (−2.4; 12.7) | 344.0550 [C17H12O8)−● (−5.2)] 329.0312 [C16H9O8)− (−2.7)] 314.0076 [C15H6O8)− (−2.6)] 301.0361 [C15H9O7)− (−2.5)] 286.0131 [C14H6O7)− (−4.3)] 242.0226 [C13H6O5)− (−4.3)] | Jaceidin 1 |

| P17 | 5.54 | [C18H33O5]− | 329.2347 (−4.2; 7.3) | 229.1454 [C12H21O4)− (−3.6)] 211.1345 [C12H19O3)− (−2.7)] 171.1025 [C9H15O3)− (−1.2)] | Pinellic acid |

| P18 | 5.71 | [C18H15O8]− | 359.0788 (−2.6; 8.2) | 344.0550 [C17H12O8)−● (−3.7)] 329.0315 [C16H9O8)− (−3.6)] 314.0082 [C15H6O8)− (−4.4)] 301.0361 [C15H9O7)− (−2.5)] 286.0132 [C14H6O7)−● (−4.1)] | Jaceidin 2 |

| P19 | 6.21 | [C16H13O5]− | 285.0777 (−4.0; 6.2) | 239.0358 [C14H7O4)− (−3.5)] 151.0040 [C7H3O4)− (−2.4)] | Sakuranetin |

| P20 | 6.75 | [C30H47O5]− | 487.3443 (−2.8; 1.8) | 469.3333 [C30H45O4)− (−2.1)] 441.3387 [C29H45O3)− (−2.9)] 343.2645 [C23H35O2)− (−0.7)] | Asiatic acid |

| P21 | 6.84 | [C30H47O5]− | 487.3442 (−2.7; 1.8) | 469.3333 [C30H45O4)− (−2.1)] 441.3387 [C29H45O3)− (−2.9)] 423.3230 [C29H43O2)− (−2.3)] 371.2965 [C25H39O2)− (−4.4)] | Acacic acid |

| P22 | 7.20 | [C30H47O4]− | 471.3492 (−2.7; 9.3) | 337.2190 [C23H29O2)− (−5.0)] | Maslinic acid |

| P23 | 7.28 | [C18H29O3]− | 293.2139 (−5.7; 8.6) | 275.2025 [C18H27O2)− (−2.9) 183.1390 [C11H19O2)− (−0.4) 171.1028 [C9H15O3)− (−1.0) | Hydroxyoctadeca-trienoic acid |

| P24 | 7.65 | [C18H31O3]− | 295.2294 (−5.1; 8.2) | 277.2182 [C18H29O2)− (−3.4) 195.1394 [C12H19O2)− (−1.5) | 13-hydroxy-9Z,11E-octadeca-trienoic acid |

| Peak | tR (min) | Ionic Formula | [M-H]− [(m/z)(Δ ppm; mSigma] | MS/MS [(m/z)(Δ ppm) (Attribution)] | Proposed Metabolite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 2.20 | [C9H9O5] | 197.0462 (−3.5; 12.8) | 179.0351 [(C9H7O4)− (−0.8)] 135.0456 [(C8H7O2)− (−0.8)] | Salvianic acid A |

| L2 | 3.11 | [C15H17O9]− | 341.0896 (−5.3; 24.9) | 251.0583 [(C12H11O6)− (−8.8)] 221.0469 [(C11H9O5)− (−6.2)] 179.0359 [(C9H7O4)− (−5.1)] 161.0246 [(C9H5O3)− (−1.0)] | Caffeoylglucose |

| L3 | 3.23 | [C15H17O9]− | 341.0897 (−5.7; 12.6) | 281.0680 [(C13H13O7)− (−4.8)] 251.0572 [(C12H11O6)− (−4.4)] 221.0465 [(C11H9O5)− (−4.3)] 179.0351 [(C9H7O4)− (−0.6)] | Caffeoylglucose isomer |

| L4 | 3.44 | [C15H17O8]− | 325.0945 (−4.8; 4.7) | 205.0513 [(C11H9O4)− (−3.2)] 193.0511 [(C10H9O4)− (−3.5)] 163.0398 [(C9H7O3)− (−1.3)] 161.0609 [(C10H9O2)− (−0.3)] 145.0295 [(C9H6O2)− (−0.2)] | Coumaric acid Glc |

| L5 | 3.48 | [C18H27O9]− | 387.1676 (−3.9; 11.8) | 299.1502 [(C15H23O6)− (−2.8)] 251.0568 [(C12H11O6)− (−2.8)] 207.1038 [(C12H15O3)− (−2.8)] 179.0347 [(C9H7O4)− (−0.1)] 161.0243 [(C9H5O3)− (−0.7)] | Hydroxy-jasmonic acid Glc |

| L6 | 3.61 | [C16H19O9]− | 355.1046 (−3.2; 6.4) | 235.0626 [C12H11O5)− (−10.2)] 193.0513 [C10H9O4)− (−5.7)] 175.0403 [C10H7O3)−(−1.7)] | Feruloylglucose |

| L7 | 3.68 | [C16H19O9]− | 355.1049 (−4.1; 5.3) | 235.0628 [C12H11O5)− (−6.8)] 193.0510 [C10H9O4)− (−2.1)] 175.0404 [C10H7O3)− (−1.6)] | Feruloylglucose isomer |

| L8 | 3.80 | [C16H19O10]− | 371.0986 (−3.3; 5.2) | 249.0642 [C9H13O8)− (−10.4)] 121.0308 [C7H5O2)− (−3.5)] | dihydroferulic acid-4-O-Glr |

| L9 | 3.85 | [C12H17O4]− | 225.1140 (−3.6; 3.5) | 167.1083 [C10H15O2)− (−3.5)] 147.0816 [C10H11O1)− (−2.9)] | Hydroxy-jasmonic acid |

| L10 | 3.85 | [C24H25O13]− | 521.1316 (−2.9; 2.6) | 359.0779 [C18H15O8)− (−1.8)] 197.0450 [C9H9O5)− (−3.8)] 161.0233 [C9H5O3)− (−1.3)] | Rosmarinyl Glc |

| L11 | 3.93 | [C17H29O10]− | 393.1780 (−3.5; 8.2) | 197.0819 [C10H13O4)− (−0.7)] 191.0574 [C7H11O5)− (−6.8)] 183.1026 [C10H11O3)− (−0.5)] 161.0463 [C6H9O5)− (−4.7)] | Hexenyl-primeveroside (HXGP) |

| L12 | 4.00 | [C21H19O12]− | 463.0879 (−0.7; 3.2) | 329.0616 [C17H13O7)− (−5.1) 0, 2X0−] 287.0577 [C15H11O6)− (−4.8) Y0−] 151.0038 [C7H3O4)− (−0.8) 13A−] 135.0457 [C6H7O2)− (−4.7)] | Eriodictyol-7-O-Glr |

| L13 | 4.01 | [C21H19O11]− | 447.0934 (−0.8; 5.5) | 327.0527 [C17H11O7)− (−5.1) 0, 2X0−] 285.0413 [C15H9O6)− (−2.9) Y0−] 284.0338 [C15H8O6)− (−4.0) (Y0−H)−●] 255.0319 [C14H7O5)− (−7.9)] 151.0035 [C7H3O4)− (−1.5) 1, 3A−] 133.0245 [C8H4O2)− (−4.3)] | Luteolin-7-O-Glc |

| L14 | 4.05 | [C21H17O12]− | 461.0740 (−3.2; 15.2) | 327.0786 [C17H11O7)− (−4.1) 0, 2X0−] 285.0416 [C15H9O6)− (−4.0) Y0−] 179.0344 [C9H7O4)− (−3.2)] 151.0032 [C7H3O4)− (−3.3) 1, 3A−] 113.0257 [C5H5O3)− (−8.4)] | Luteolin-7-Glr |

| L15 | 4.22 | [C24H23O12]− | 503.1215 (−3.9; 21.4) | 341.0892 [C15H17O9)− (−4.2)] 281.0681 [C13H13O7)− (−5.1)] 251.0574 [C12H11O6)− (−4.9)] 161.0244 [C9H5O3)− (−0.4)] | Dicaffeoyl-Glc |

| L16 | 4.26 | [C21H19O10]− | 431.0994 (−2.9; 8.5) | 269.0453 [C15H9O5)− (−1.2) Y0−] 268.0391 [C15H8O5)− (−5.1) (Y0−H)−●] 179.0351 [C9H7O4)− (−0.6)] 151.0399 [C8H7O3)− (−1.4)] | Apigenin-7-O-Glc |

| L17 | 4.30 | [C21H17O11]− | 445.0781(−0.9; 6.2) | 269.0453 [C15H9O5)− (−3.7) Y0] 197.0461 [C9H9O5)− (−4.5)] 179.0343 [C9H7O4)− (−4.1)] 161.0234 [C9H5O3)− (−6.2)] | Apigenin-7-O-Glr |

| L18 | 4.35 | [C18H15O8]− | 359.0787(−4.0; 14.2) | 197.0460 [C9H9O5)− (−2.2)] 179.0349 [C9H7O4)− (−2.2)] 161.0242 [C9H5O3)− (−1.2)] 135.0450 [C8H7O2)− (−1.2)] | Rosmarinic acid |

| L19 | 4.50 | [C36H29O16]− | 717.1481(−3.1; 6.8) | 509.0945 [C31H16O8)− (−1.0)] 339.0523 [C11H14O12)− (−2.2)] 321.0421 [C11H12O11)− (−0.5)] 295.0621 [C17H11O5)− (−2.8)] | Salvianolic acid B |

| L20 | 5.13 | [C17H13O6]− | 313.0724 (−2.1; 3.8) | 267.1610 [C15H23O4)− (−3.0)] 207.1399 [C13H19O2)− (−4.2)] 161.0242 [C9H5O3)− (−1.2)] 151.0396 [C8H7O3)− (−3.3)] 133.0300 [C8H5O3)− (−3.8)] | 3,7-Dihydroxy-3′,4′dimethoxy-flavone |

| L21 | 5.19 | [C15H9O5]− | 269.0460 (−1.8; 4.0) | 241.0513 [C14H9O4)− (−3.2)] 151.0036 [C7H3O4)− (−0.3) 1, 3A−] 117.0339 [C8H5O)− (−6.0)] | Apigenin |

| L22 | 5.54 | [C18H33O5]− | 329.2347 (−4.2; 7.3) | 229.1454 [C12H21O4)− (−3.6)] 211.1345 [C12H19O3)− (−2.7)] 171.1025 [C9H15O3)− (−1.2)] | Pinellic acid |

| L23 | 5.99 | [C30H45O6]− | 501.3231 (−1.9; 5.0) | 483.3130 [C30H43O5)− (−2.8)] 441.3028 [C28H41O4)− (−4.0)] 233.0470 [C12H9O5)− (−6.1)] | Medicagenic acid |

| L24 | 5.02 | [C30H47O6]− | 503.3389 (−2.1; 5.0) | 485.3228 [C30H45O5)− (−2.7)] 453.3023 [C29H41O4)− (−2.7)] 441.3383 [C29H43O4)− (−2.0)] 409.3125 [C28H41O2)− (−3.2)] 233.0465 [C12H9O5)− (−4.1)] | Madecassic acid |

| L25 | 6.75 | [C30H45O5]− | 485.3283 (−2.3; 9.6) | 467.3177 [C30H43O4)− (−2.3)] 425.3071 [C28H41O3)− (−2.3)] 357.2815 [C24H37O2)− (−4.4)] | Quillaic acid |

| L26 | 6.89 | [C30H47O5]− | 487.3442 (−2.7; 1.8) | 469.3333 [C30H45O4)− (−2.1)] 441.3387 [C29H45O3)− (−2.9)] 425.3435 [C29H45O2)− (−2.3)] 371.2965 [C25H39O2)− (−4.4)] | Acacic acid |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Serrano, C.; Lopes, V.; Serra, O.; Gaspar, C.; Barata, A.M.; Soares, A.; Oliveira, M.C. Metabolomic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Methanolic Extracts of Mentha pulegium L. and Lavandula stoechas L. from the Portuguese Flora. AppliedChem 2026, 6, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010003

Serrano C, Lopes V, Serra O, Gaspar C, Barata AM, Soares A, Oliveira MC. Metabolomic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Methanolic Extracts of Mentha pulegium L. and Lavandula stoechas L. from the Portuguese Flora. AppliedChem. 2026; 6(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSerrano, Carmo, Violeta Lopes, Octávio Serra, Carlos Gaspar, Ana Maria Barata, Andreia Soares, and M. Conceição Oliveira. 2026. "Metabolomic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Methanolic Extracts of Mentha pulegium L. and Lavandula stoechas L. from the Portuguese Flora" AppliedChem 6, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010003

APA StyleSerrano, C., Lopes, V., Serra, O., Gaspar, C., Barata, A. M., Soares, A., & Oliveira, M. C. (2026). Metabolomic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Methanolic Extracts of Mentha pulegium L. and Lavandula stoechas L. from the Portuguese Flora. AppliedChem, 6(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedchem6010003