Abstract

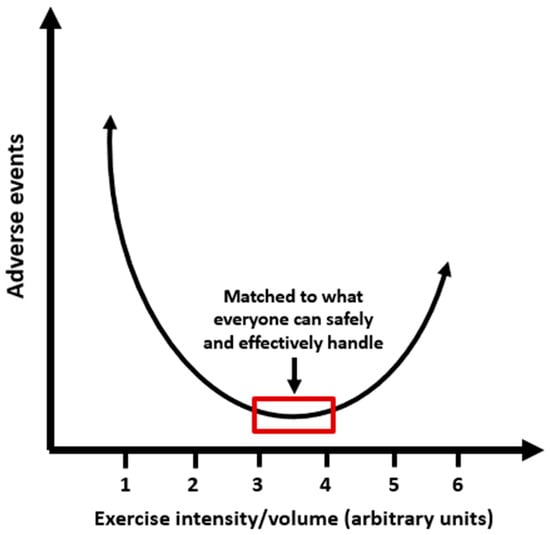

Physical inactivity, which currently dominates the lifestyles of most people, is linked to chronic metabolic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease, all of which share insulin resistance as a common pathogenic mechanism. Both epidemiological and experimental intervention studies have consistently shown that physical activity and exercise can reduce the incidence of these diseases and significantly improve their clinical outcomes, resulting in enhanced quality of life and well-being. This approach includes various forms of aerobic and anaerobic/resistance training, either individually or in combination, leading to reduced insulin resistance and visceral fat, regardless of the weight loss achieved through diet. It also lowers inflammatory responses and oxidative stress, a harmful mechanism that leads to cellular damage, and positively impacts immunological regulation. Regarding timing, physical activity/exercise appears to produce better outcomes for metabolic control, particularly in individuals with T2D, when performed after dinner compared to other times of the day. In addition to organized physical activity/exercise sessions, practices such as interrupting prolonged sitting with frequent breaks every 30 min that involve muscular contractions and increased energy expenditure may also benefit metabolic health. Minimizing physical inactivity, prolonged sitting at work or during leisure time, can decrease the frequency of metabolic illness, enhance health and quality of life, and avert premature death. However, intense exercise may not always be the most beneficial option for health, and the relationship between adverse events and the intensity of physical activity or exercise resembles a U-shaped or J-shaped curve. Physical activity/exercise should be performed at a suitable intensity that aligns with personal capability. In this primarily clinically focused review, we discuss the effects of insulin on target tissues, the significance of insulin sensitivity in metabolic regulation, how physical inactivity contributes to insulin resistance, the different types of exercise and their impact on insulin effectiveness, and the importance of physical activity and exercise in managing metabolic diseases.

1. Introduction

Our modern life is characterized by a sedentary lifestyle, defined by prolonged sitting, reduced energy expenditure, high consumption of energy-dense foods, chronic psychological stress, sleep disturbances, and environmental pollution. These factors do not operate in isolation; instead, they work together, leading to metabolic syndrome, which includes a cluster of metabolic and hemodynamic abnormalities, such as obesity (especially abdominal), type 2 diabetes (T2D), chronic hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. These conditions share insulin resistance as a common pathogenic mechanism. Insulin resistance and metabolic abnormalities induce endothelial dysfunction, vascular damage, and cardiovascular disease, a leading cause of death in modern societies [1]. Insulin resistance is also accompanied by hyperinsulinemia, an additional factor that exacerbates hypertension and cardiovascular disease, and it may induce certain forms of cancer [2,3]. Therefore, reducing insulin resistance in everyday life is critical for alleviating metabolic stress [4]. Physical activity and exercise are the most potent modulators of metabolism, increasing tissue sensitivity to insulin. They provide a safe and effective therapeutic approach for obesity and T2D, protect against cardiovascular disease, reduce mortality, strengthen immunity, promote psychological well-being, and prevent cognitive and physical decline, thereby serving as a cornerstone for maintaining a healthy lifestyle [5].

Physical activity involves any movement of the body that requires energy expenditure. It includes all forms of movement, such as climbing stairs, walking, doing household chores, gardening, or even standing (which involves muscle contractions to maintain posture) as part of daily life. Conversely, exercise usually refers to a structured, planned, repetitive, and specifically designed form of physical activity aimed at maintaining or enhancing physical fitness, such as flexibility, strength, and cardiovascular health [6]. These practices are strongly recommended for maintaining metabolic health, so they should be started as early as possible and continued throughout life.

This narrative review aims to integrate current evidence regarding the harmful effects of physical inactivity on the development of insulin resistance and metabolic dysregulation, as well as the role of physical activity, as suggested by scientific societies, or by utilizing less time-consuming alternatives to alleviate insulin resistance and reduce the risk of metabolic diseases and cardiovascular events, while providing a comparison of benefits and harms. Relevant literature was retrieved by searching PubMed for terms such as insulin action, insulin resistance, sedentary lifestyle, physical inactivity, exercise timing, adverse events, benefits and harms, quality of life, immunological regulation, autonomic function, cardiovascular risk, and metabolic diseases, all related to physical activity and exercise. Additional references were identified by analyzing the retrieved publications and the authors’ files. In the following sections of this primarily clinically oriented review, we examine the effects of insulin on target tissues, emphasize the importance of insulin sensitivity in metabolic regulation, discuss how physical inactivity contributes to insulin resistance, review different types of training and their impact on insulin effectiveness, and highlight the significance of physical activity in managing metabolic diseases.

2. Physiology of Insulin Effects on Target Tissues

Insulin plays a crucial role in regulating glucose homeostasis by affecting insulin-sensitive tissues. Blood glucose levels are managed by the rates of glucose production in the liver through glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, as well as by glucose removal from peripheral tissues, primarily skeletal muscle. Adipose tissue provides non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) as an alternative fuel for skeletal muscle and liver when blood glucose levels are low. These mechanisms are supported by balanced adjustments in insulin secretion, which maintain tight control of the metabolic system and integrate lipid and carbohydrate metabolism across tissues, thus allowing metabolism to adapt to changes in energy requirements under various circumstances [7]. Changes in insulin secretion and action are coordinated by the central nervous system (CNS) to ensure appropriate substrate switching between tissues and to meet metabolic needs, such as during the postabsorptive-to-postprandial transition or during exercise [8]. In the postabsorptive state (fasting), the liver is the primary site for glucose production and release into the systemic circulation. In contrast, in the postprandial state, skeletal muscle is the leading site for glucose disposal [7]. Insulin decreases the rates of glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis, and endogenous glucose production, while increasing glycogen synthesis in the liver. It also promotes glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis in skeletal muscle, stimulates lipid synthesis, and reduces lipolysis along with the production of NEFA and glycerol in adipose tissue. Additionally, insulin acts on the vascular endothelium to promote vasodilation and capillary recruitment, thereby enhancing blood flow to muscle and adipose tissue [9,10,11] (Figure 1). The insulin-mediated increases in blood flow and insulin’s effects on tissue glucose uptake and metabolism are interconnected processes, making them essential determinants of tissue sensitivity to insulin [9,12]. In skeletal muscle, increased blood flow following a meal or during exercise enhances the delivery of substrates and hormones for metabolism [13,14]. In adipose tissue, the postprandial increase in blood flow induced by insulin is crucial for clearing NEFA from the bloodstream, facilitating insulin-stimulated glucose utilization in skeletal muscle. This explains the overall greater increases in blood flow in adipose tissue during the postprandial state, even though insulin-stimulated glucose disposal rates in muscle are approximately three times higher than those in adipose tissue [14]. In T2D, insulin-stimulated blood flow rates in muscle and adipose tissue are significantly impaired from the early stages of the disease, contributing to the development of insulin resistance and metabolic dysregulation [15,16]. Dysfunction of the vascular endothelium significantly contributes to atherogenesis and the development of cardiovascular disease [17].

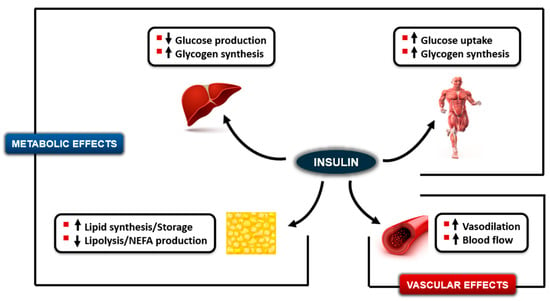

Figure 1.

Effects of insulin to decrease endogenous glucose production and increase glycogen storage in the liver, increase glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis in muscle, increase lipid synthesis and decrease lipolysis in adipose tissue (Metabolic effects), and increase vasodilation and blood flow rates in muscle and adipose tissue (Vascular effects). Upward arrows indicate an increase; downward arrows indicate a decrease.

3. The Importance of Insulin Sensitivity in Metabolic Regulation

The sensitivity of tissues to insulin plays a crucial role in regulating metabolism, thereby supporting overall metabolic health. The amount of insulin released by β-cells at any given time depends on the metabolic needs of insulin-sensitive tissues [7]. Skeletal muscle accounts for a significant portion of body mass and is the primary tissue responsible for glucose disposal. Therefore, if insulin sensitivity in muscle improves, such as through physical activity or exercise, the handling of increased glucose entry into the bloodstream can happen without a significant change in blood insulin levels; blood glucose would be controlled by changes in insulin sensitivity at the tissue level rather than by an increase in insulin secretion, and as a result, blood insulin levels [7]. Supporting this, Kahn et al. [18] demonstrated that β-cells and insulin-sensitive tissues interact in a tightly regulated reciprocal manner. When insulin sensitivity is high, insulin release is low, and vice versa. Increased physical activity/exercise is essential for improving insulin sensitivity, thereby preventing significant hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in all situations. This is of considerable physiological importance, as hyperglycemia above an optimal level (>140 mg/dL) acts as a prothrombotic factor, inducing oxidative stress and protein glycosylation, ultimately disrupting cell metabolism [19,20,21]. Additionally, hyperinsulinemia promotes growth, increases the risk of hypoglycemia, intensifies glucose fluctuations, damages the endothelium, leads to proinflammatory and prothrombotic abnormalities, and contributes to weight gain and the development of hypertension, ultimately inducing or worsening pre-existing insulin resistance [22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

4. Gender Differences in Insulin Sensitivity

Gender plays a crucial role in the development of insulin resistance and metabolic diseases. Insulin resistance is generally less common in premenopausal women than in similarly aged men. In contrast, after menopause, the incidence of insulin resistance in women increases and becomes similar to that in men, raising the risk of developing metabolic diseases [29]. These gender differences are primarily because estrogens, the main female sex hormones, may protect tissues and cells from insulin resistance [30]. During their reproductive years, a significant factor contributing to increased insulin sensitivity in women is the accumulation of adipose tissue, mainly in the gluteal and femoral regions, rather than in the visceral and subcutaneous abdominal areas, as seen in men. This latter accumulation is closely linked to the development of insulin resistance and metabolic diseases [31]. Estrogens can also protect β-cells from apoptosis and support fasting- and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Concerning insulin action, they enhance its ability to suppress gluconeogenesis and endogenous glucose production, decrease hepatic insulin degradation, reduce cellular oxidative stress, a key factor in insulin resistance, and promote nitric oxide production in the vascular endothelium, thereby improving vasodilation and blood flow [32].

5. The Adverse Effects of Physical Inactivity on the Development of Insulin Resistance and Metabolic Dysregulation

Physical inactivity is a major global cause of death, ranking as the fourth leading risk factor for overall mortality worldwide. It significantly contributes to the development of insulin resistance in various tissues, including the brain, skeletal muscle, liver, adipose tissue, and vascular endothelium. Additionally, it is linked to severe chronic metabolic complications such as T2D, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, muscle atrophy or sarcopenia, and atherosclerosis or cardiovascular disease [33], as well as sleep disturbances, cognitive impairment, and excessive stress issues in children, adolescents, and adults [34,35].

In conditions such as obesity and T2D, the pathophysiology of insulin resistance begins in adipose tissue. Conversely, during physical inactivity, it begins in muscle. Several studies have investigated the effects of short- or long-term physical inactivity on insulin action. These studies employ methods such as bed rest, daily step reduction, sitting, one-leg inactivity, or stopping exercise in trained individuals. Insulin action was evaluated using euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps, postprandial sensitivity indexes from the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and the fasting index HOMA-IR.

5.1. Short-Term Physical Inactivity

Regarding short-term physical inactivity, Stuart et al. [36] examined healthy individuals before and after 7 days of strict bed rest. These researchers performed five-step euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps using sequential infusions of insulin at physiological and maximum levels, along with intravenous administration of [3-3H]glucose, to measure glucose turnovers. The results showed that during short-term physical inactivity, insulin resistance mainly affected skeletal muscle. Insulin normally inhibited endogenous glucose production, but insulin-stimulated glucose uptake into muscle decreased by over 70% at insulin levels within the physiological range, and returned to normal with maximum insulin levels, indicating reduced sensitivity but preserved responsiveness [36]. Therefore, short-term (less than 10 days) physical inactivity can cause insulin resistance in muscle, but not in the liver or adipose tissue. The mechanisms behind insulin resistance and declining metabolic health involve muscle atrophy due to inactivity (~4% muscle mass loss and ~8% strength decrease), along with reduced expression of metabolic genes—especially those related to GLUT-4, hexokinase 2, and mitochondrial function—leading to lower protein synthesis and about a 30% decrease in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake measured by euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps [37,38,39,40]. Additionally, insulin stimulates the expression of genes associated with inflammation and endoplasmic reticulum stress, thereby affecting protein synthesis. Fuel metabolism shifts toward increased mitochondrial glucose oxidation and decreased NEFA oxidation [41]. Insulin resistance leads to increased β-cell secretory activity and hyperinsulinemia, while fasting and postprandial glucose levels remain within the normal range. Intramuscular accumulation of lipids and toxic lipid byproducts, reduced blood flow, and elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative stress do not seem to contribute to the rapid development of insulin resistance during short-term physical inactivity [38,39,40]. Similar mechanisms have been reported in studies employing short-term daily step reduction to assess physical inactivity [42] (Figure 2).

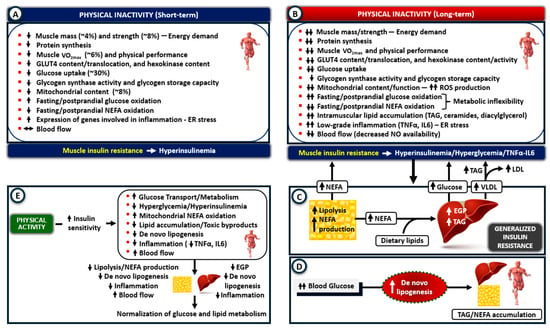

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of insulin resistance after physical inactivity (PI). (A) Short-term PI primarily impacts skeletal muscle by causing atrophy, reducing glucose uptake and metabolism, and impairing mitochondrial function and fat oxidation. These defects quickly lead to insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia without altering blood glucose levels. (B) Prolonged PI worsens muscle atrophy and insulin resistance by intensifying these processes, increasing oxidative stress and low-grade inflammation, and stimulating TNF-α and IL-6 production. An additional reduction in fat oxidation leads to lipid accumulation and the formation of toxic lipid byproducts (lipotoxicity). (C) Hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and the leakage of TNF-α and IL-6 into the circulation contribute to insulin resistance in adipose tissue, liver, and vascular endothelium. The overproduction of NEFA from adipose tissue lipolysis promotes gluconeogenesis, increases glucose production, and leads to TAG accumulation in the liver, while further inhibiting insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in muscle. (D) Along with elevated blood triglycerides, de novo lipogenesis also contributes to lipid accumulation in insulin-sensitive tissues. (E) Physical activity reverses inactivity-related muscle metabolic defects, restores insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue and liver, and normalizes glucose and lipid metabolism (ER, endoplasmic reticulum; EGP, endogenous glucose production; LDL, Low-density lipoprotein; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acids; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TAG, triglycerides; VLDL, very-low-density lipoproteins; VO2max, maximum rate of oxygen use during exercise). Upward arrows indicate an increase; downward arrows indicate a decrease.

5.2. Long-Term Physical Inactivity

Prolonged physical inactivity sustains muscle insulin resistance, while loss of muscle mass and atrophy continue to worsen, further reducing GLUT-4, hexokinase, and glycogen synthase activity, as well as mitochondrial oxidative capacity. Additionally, the gradual development of low-grade local inflammation promotes immune cell infiltration into muscle (macrophages), which secrete TNF-α and IL-6, potent insulin-resistant cytokines. The parallel development of oxidative stress and intramuscular lipid accumulation contributes to the worsening of muscle insulin resistance. In the postabsorptive state, a shift in fuel metabolism favors carbohydrate oxidation, increasing it by up to 21%, while lipid oxidation decreases by as much as 37%. In the postprandial state, glucose oxidation increases by only 6%, while lipid oxidation decreases by 40% [38,42,43,44]. These disturbances cause metabolic inflexibility in muscle—the inability to switch between glucose and lipid oxidation in response to metabolic needs—a key factor in the development of insulin resistance in metabolic diseases [7,45]. These conditions further exacerbate the imbalance between nutrient intake and substrate utilization, leading to systemic metabolic dysregulation [38,46] (Figure 2).

Muscle insulin resistance and severe impairment of glucose uptake after meals lead to excessive postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, which, along with leakage of TNF-α and IL-6 into circulation, cause generalized insulin resistance involving adipose tissue, the liver, and vascular endothelium [38,47,48,49,50]. The latter decreases insulin-stimulated blood flow in adipose tissue, impairing the clearance of NEFA and triglycerides from the circulation. Reduced blood flow can also cause ischemia and cell damage [51]. Increased adipose tissue lipolysis releases NEFA, which are transported to muscle and vascular endothelial cells, further worsening insulin resistance. In the liver, NEFA oversupply stimulates gluconeogenesis and endogenous glucose production, and enhances their esterification into triglycerides. Subsequently, triglycerides are packed into VLDL particles, released into the bloodstream, and delivered to muscle, where they are hydrolyzed into NEFA and re-esterified into triglycerides rather than being oxidized in mitochondria. The imbalance between higher NEFA uptake and lower oxidation drives NEFA metabolism toward producing toxic byproducts, such as ceramides, diacylglycerol, and fatty acyl-CoA. This creates a lipotoxic insulin-resistant environment that disrupts glucose metabolism [38,40,42,44,49]. An additional source of NEFA accumulation in insulin-sensitive tissues is de novo lipogenesis. This process converts excess circulating glucose into fatty acids, which are then esterified into triglycerides when glycogen stores are full. De novo lipogenesis can occur in muscle, adipose tissue, and the liver, contributing to increased lipid storage (Figure 2).

In metabolic diseases, insulin resistance occurs not only in the liver and peripheral tissues but also in the CNS, leading to decreased insulin-mediated stimulation of muscle glucose uptake and suppression of hepatic glucose production, and increased lipolysis in adipose tissue [8]. A study by Kullmann et al. [52] investigated the effects of eight weeks of supervised aerobic exercise on insulin action in the brain among sedentary, insulin-resistant, obese, and overweight individuals. Brain insulin action was assessed using functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after intranasal insulin administration, both before and one week after the exercise intervention. Insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues was evaluated through OGTT and muscle biopsies, while body fat distribution was assessed via whole-body MRI. Exercise training restored insulin action in the brain, resulting in improved post-load insulin sensitivity, enhanced mitochondrial respiratory capacity in skeletal muscle, and reduced adipose tissue mass. The authors concluded that exercise is an effective intervention to ameliorate brain insulin resistance in sedentary individuals, thereby reducing metabolic risk factors associated with obesity [52].

5.3. Clinical Relevance

In individuals with T2D who already have established insulin resistance, even short-term physical inactivity can lead to a significant increase in insulin resistance. Notably, bed rest for 9–10 days [53,54,55], or a 14-day step reduction [56] in people with a 1st degree relative with T2D or born with low birth weight and therefore at high risk of developing T2D showed significant metabolic and vascular insulin resistance in muscle (evaluated by euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamps and infusions of stable isotopes, or with OGTT-derived insulin sensitivity indices), which was more pronounced than in controls. Hepatic and adipose tissue insulin resistance, along with increased lipolysis, were observed only in individuals predisposed to T2D compared with controls.

The consequences of physical inactivity on metabolic dysregulation may depend on individuals’ fitness level. Smorawinski et al. [57] compared sedentary individuals with endurance- and strength-trained athletes after an OGTT, measuring plasma glucose and insulin levels. After 3 days of bed rest, athletes demonstrated greater compensation for the induced reductions in insulin sensitivity compared to sedentary individuals.

Leg vasculature is highly susceptible to atherosclerosis, and prolonged inactivity has been shown to impair endothelial function in the lower limbs [58,59]. Restaino et al. [60] investigated the effects of prolonged sitting on leg endothelial function in lean healthy men. They showed that sitting for as little as 3 h induced endothelial dysfunction and reduced blood flow in the popliteal artery by 60%. In a review article, Hamilton et al. [61] examined the effects of non-exercise physical activity in daily life on metabolic regulation. They showed that it can rapidly trigger molecular responses, leading to impaired lipid metabolism in muscle and insulin resistance, thereby increasing the risk of metabolic syndrome, obesity, T2D, and cardiovascular disease [61]. These results are clinically significant for individuals with low occupational activity, such as taxi or bus drivers.

One of the most common behaviors associated with prolonged sitting is watching television. In an epidemiological study of 8800 Australian adults, Dunstan et al. [62] showed a positive linear correlation between the time spent watching television (1 to 6 h per day) and an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality over a median follow-up of about 7 years; this correlation was independent of increased caloric intake (snacking) during television viewing. In a prospective study involving 888 participants, Wennberg et al. [63] examined whether television viewing and low leisure-time physical activity during adolescence could predict the development of Metabolic Syndrome in mid-adulthood. The overall prevalence of obesity or overweight and Metabolic Syndrome at age 43 was 55% and 27%, respectively. The results revealed an independent dose–response relationship between television viewing and leisure-time physical activity during adolescence. This relationship contributed to the development of Metabolic Syndrome and some of its components, including central obesity, low HDL cholesterol, and hypertension, as well as cardiovascular disease in mid-adulthood [63].

Physical inactivity-induced insulin resistance and the subsequent endothelial damage can lead to the development of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in people with or without diabetes (T2D or T1D) [64,65,66,67,68]. As described earlier, insulin resistance is associated with compensatory hyperinsulinemia, which may also promote the development of cardiovascular disease through various effects on the vascular endothelium. It acts as an independent risk factor by increasing coagulation and decreasing fibrinolysis, both of which contribute to a prothrombotic state that increases the risk of ischemic heart disease [69]. Meigs et al. [70] investigated the association between fasting plasma insulin levels and hemostatic factors in 2962 overweight or obese individuals with normal or impaired glucose tolerance, including those with undiagnosed T2D. In the latter two groups, fasting plasma insulin levels were higher than in individuals with normal glucose tolerance, indicating insulin resistance. In all participants, fasting plasma insulin levels showed a strong positive association with markers of impaired hemostasis. The authors concluded that the increased risk of cardiovascular disease associated with hyperinsulinemia may be mediated, at least in part, by an enhanced thrombotic potential, characterized by heightened coagulation and reduced fibrinolytic activity. In this context, impaired fibrinolysis plays a more significant role in conditions of impaired glucose tolerance [70]. Therefore, avoiding physical inactivity is crucial for maintaining insulin sensitivity and its anabolic effects, which helps lower the risk of metabolic diseases and cardiovascular complications.

In summary, prolonged inactivity and muscle atrophy, combined with reduced energy demand and an imbalance between nutrient intake and substrate utilization, lead to insulin resistance—initially in muscle and then spreading to the liver, adipose tissue, and vascular endothelium—resulting in postprandial hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and hypertriglyceridemia. Lower mitochondrial oxidation of NEFA causes lipid accumulation not only in muscle but also in adipose tissue and the liver, which, along with de novo lipogenesis, leads to lipotoxicity. Physical activity and exercise reverse the inactivity-related muscle metabolic defects by directing NEFA toward mitochondrial oxidation instead of storage and the formation of toxic byproducts. This improves insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake and glycogen synthesis, while also decreasing inflammation, hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and de novo lipogenesis. The subsequent reduction of insulin resistance in adipose tissue, with decreased lipolysis and NEFA production, and in the liver, with reduced endogenous glucose production and lipid accumulation, helps restore normal glucose and lipid metabolism [71,72] (Figure 2).

6. Types of Exercise

Depending on the primary mechanisms muscles use to obtain energy, exercise can be classified as aerobic or anaerobic. Aerobic exercise involves sustained, continuous effort that activates multiple muscle groups. Activities such as brisk walking, jogging, cycling, and swimming provide a physiological stimulus for optimal mitochondrial function and muscle oxidative capacity. In contrast, anaerobic exercise is characterized by shorter durations involving smaller muscle groups, such as sprinting or weightlifting with free weights, weight machines, or elastic resistance bands, which stimulate myofibrillar protein synthesis [73]. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) is a popular workout that involves short bursts of intense anaerobic exercise (e.g., cycling on a stationary cycle ergometer), followed by brief periods of passive or active aerobic recovery, thereby enhancing both muscle strength and endurance [74,75]. In active muscles, a constant supply of ATP is maintained through both aerobic and anaerobic metabolic pathways that work synergistically rather than independently. This process involves interactions between exercising muscles and distant tissues and organs, such as the liver, adipose tissue, cardiovascular system, and brain, to provide energy, sustain blood glucose levels within the euglycemic range, and prevent hypoglycemia [76].

At rest, typically during sleep at night, muscles obtain energy mainly from the oxidation of NEFA rather than glucose [7,77]. During exercise, the increasing energy demands of working muscles require a significant shift in the mobilization and oxidation of carbohydrates and lipids, depending on the mode, intensity, and duration of exercise.

6.1. Aerobic (Endurance) Training

In a comprehensive systematic study, Romijn et al. [78] investigated the effects of aerobic exercise intensity (low/25% VO2max, moderate/65% VO2max, or high/85% VO2max) and duration (30 or 120 min) on the utilization of glucose and NEFA in endurance-trained cyclists in the fasting state over three consecutive days while using a stationary cycle ergometer. Indirect calorimetry and stable-isotope infusions were used to estimate energy turnover and substrate mobilization. This study [78] and others [13,79,80,81,82,83,84,85] described the hormonal changes and energy sources involved during aerobic exercise.

At the onset of exercise, insulin secretion decreases while glucagon secretion increases. The activation of the sympathetic nervous system increases from 2- to 4-fold, reaching up to 300-fold during low-, moderate-, and high-intensity exercise. This increase mediates the rise in plasma catecholamine levels, blood pressure (BP), and blood flow to muscles, facilitating the effective delivery of hormones and substrates. This process enhances hepatic glucose production and adipose tissue lipolysis. Plasma growth hormone levels and cortisol increase with exercise intensity, supplementing the effects of catecholamines [13,78,79,80]. The decrease in plasma insulin and the increase in counterregulatory hormones stimulate endogenous glucose production by about 2-, 4-, and 6-fold during low-, moderate-, and high-intensity exercise, respectively, via glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. This process helps maintain plasma glucose levels within the euglycemic range. It enhances lipolysis in adipose tissue, releasing NEFA and glycerol, which serve as stimulators and a substrate, respectively, for endogenous glucose production [13,78,80].

During low-intensity 30-min exercise, muscles primarily obtain energy from circulating NEFA produced by lipolysis in peripheral adipose tissue (90%), rather than from glucose (10%). The slight increase in glucose oxidation is fully met by glucose uptake from circulation; therefore, muscle glycogen is not utilized. Additionally, lipolysis from intramuscular triglycerides does not increase [78]. As exercise intensity increases from low to moderate, there is a progressive shift in energy utilization from NEFA (50%, derived equally from circulating and muscle triglycerides) to glucose (50%, primarily from muscle glycogen stores for anaerobic metabolism and lactate production) [78,85,86,87]. As exercise intensity increases from moderate to high, energy consumption relies almost exclusively on glucose (10% from circulating glucose and 60% from muscle glycogen) rather than on NEFA (30% from circulating fatty acids or muscle triglyceride stores) [78,87]. Increasing exercise duration from 30 to 120 min does not change substrate contribution at low intensity. However, a gradual increase in reliance on circulating NEFA and glucose occurs at moderate to high intensities, resulting in a further decrease in muscle glycogen stores [87]. NEFA originate from dietary sources, the breakdown of triglycerides in adipose tissue, intramyocellular triglycerides, and de novo lipogenesis [88].

In a classic study, Wahren et al. [13] investigated substrate utilization at rest and during aerobic exercise (40 min on a bicycle ergometer) at increasing workloads ranging from light to moderate to heavy intensity in healthy, sedentary participants not regularly engaged in training programs. During exercise, insulin secretion and blood levels decrease, while muscle glucose uptake increases significantly due to muscle contractions. Glucose uptake was enhanced by a greater than 10-fold rise in muscle blood flow. Energy consumption in muscle during exercise in these sedentary individuals relied entirely on glucose oxidation from hepatic glycogenolysis, rather than on gluconeogenesis, due to elevated plasma glucagon and adrenaline levels [13].

Glucose uptake rates in contracting muscles increase independently of insulin due to enhanced intrinsic activity and translocation of GLUT4 transporters from intracellular pools to the myocellular surface membrane [13,81,82,83]. Hexokinase activity and glucose phosphorylation, as well as blood flow rates and mitochondrial oxidative capacity, all increase during exercise to support the rise in muscle glucose utilization [84,85,89]. A study by Perseghin et al. [85] showed that insulin sensitivity and insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in muscle can persist for at least 48 h after even a single session of aerobic exercise, involving three sets of stair-climbing on a machine at 65% of VO2max, with each set lasting 15 min. Notably, glycogen depletion increases glucose storage capacity in muscle, enhancing insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake by increasing GLUT-4 content and activity [90,91]. The increase in insulin sensitivity is also improved by the mobilization of ectopic lipids in muscle during exercise. Additionally, increased glucose uptake and metabolism, along with glycogen storage in muscle, may reduce the need for de novo lipogenesis, which typically occurs when blood glucose levels are excessively high (glucose oversupply). This can lessen the strain on adipose tissue and liver for storing unused energy, thereby reducing inflammation and their lipid reserves [92].

In summary, aerobic (endurance) training in physically active individuals involves a complex interaction between glucose and lipids. At low to moderate intensities, muscle primarily relies on NEFA for energy, as their oxidation rates are slow and require sufficient time and oxygen for ATP production. As exercise intensity increases, energy demand exceeds NEFA oxidation’s capacity to supply ATP. Consequently, muscle relies more on glucose for energy, initially from the circulation and then from muscle glycogen. In sedentary individuals not engaged in regular exercise, the energy required for muscle contractions during moderate-intensity aerobic exercise depends on glucose oxidation from liver glycogenolysis.

6.2. Anaerobic (Resistance) Training

Exercising against resistance is popular because it enhances body composition by increasing lean body mass, a goal that aerobic exercise alone cannot achieve to the same extent. It is also associated with reduced mortality and has an additive effect on the benefits of aerobic exercise in lowering cardiovascular risk [93]. Although the mechanisms for enhancing insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake into muscle cells are similar to those described earlier (increases in glucose transport and blood flow rates, Section 6.1), anaerobic exercise (such as weightlifting and sprinting) primarily depends on glucose derived from muscle glycogen for ATP production [76]. The anaerobic metabolism of glucose in the glycolytic pathway produces lactate, which is then converted back into glucose in the liver. The recycling of glucose between muscle and liver forms a “substrate cycle” (Cori cycle). The role of substrate cycles in metabolic pathways is crucial because they can enhance the pathway’s sensitivity to external signals, such as hormones (e.g., catecholamines, which increase through sympathetic nervous system activity during exercise) [94]. They also generate heat, an aspect of substrate cycling that contributes to weight control and, therefore, obesity [95].

A key effect of resistance exercise is its ability to enhance both the quantity and quality of muscle mass through the IGF-1/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathways [96,97]. In contrast to aerobic exercise, resistance exercise has been shown to increase IGF-1 expression, leading to subsequent GLUT-4 translocation and enhanced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle preparations in vitro [98]. Increased plasma IGF-1 concentrations have been recorded during high-intensity resistance training [99]. Earlier studies have demonstrated that IGF-1, with its insulin-like effects, increases the apparent sensitivity of skeletal muscle to insulin, either in vitro [100] or following acute or chronic (10-day) administration in vivo [101].

Muscle hypertrophy induced by resistance training has attracted significant attention due to its effects on glucose homeostasis and the underlying mechanisms. In lean young women, Poelhman et al. [102] compared the mechanisms of insulin-stimulated muscle glucose disposal (euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps) after 6 months of endurance training (supervised jogging of increasing duration and intensity with or without resting periods) or resistance training (using free weights and weight machines involving all major muscle groups, performed on three non-consecutive days per week). The results showed that both endurance and resistance exercise increased glucose disposal rates by 16% and 10%, respectively. After resistance training, this improvement was mainly due to increased muscle mass, whereas after endurance exercise, it was primarily due to changes in intrinsic metabolic pathways involved in glucose metabolism [102]. In resistance exercise, increased muscle vascularization and blood flow contribute to increased insulin-stimulated glucose disposal [103].

In summary, during resistance (anaerobic) workouts, with their intense, short bursts of activity, the rates of NEFA oxidation and oxygen delivery are too slow and inadequate to meet the rapid ATP demand. Therefore, muscle must rely on breaking down glycogen to lactate (anaerobic glycolysis), increasing the activity of the Cori cycle for ATP production.

6.3. High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT)

HIIT involves repeated short bursts of high-intensity or vigorous exercise, usually sprint-based or resistance-based, performed at 64–90% VO2max or 77–95% of maximum heart rate for 20 s to several minutes, with rest or lower-intensity recovery periods in between. As a result, it can be clinically significant because it improves both anaerobic and aerobic performance simultaneously. This helps to reduce insulin resistance by lowering body weight, increasing muscle glucose uptake through enhanced GLUT-4 activity and content, and depleting glycogen, as described in Section 6.1 and Section 6.2. HIIT may be more effective than continuous exercise in reducing muscle insulin resistance due to its interval-based modality or greater exercise intensity [104]. Although HIIT is considered a short, time-efficient training method, a full HIIT session—including warm-up, recovery, and cool-down—can exceed 20 min, thereby decreasing overall time efficiency. Therefore, Metcalfe et al. [105] proposed a shorter intervention, “Reduced-Exertion HIIT” (REHIT), consisting of three exercise sessions per week for six weeks. Each session lasted 10 min (totaling 30 min per week), involving one low-intensity cycling session and one or two intense sprints. In sedentary healthy individuals, REHIT increased insulin sensitivity, as measured by the ISI index from the OGTT, by 28% compared to non-exercised controls.

6.4. Comparison of the Effects of Exercise Modalities in T2D and Obesity

As a general rule, the amount of physical activity/exercise may be more critical for achieving optimal glycemic and lipid control than the specific type or the intensity of the activity performed [106,107]. Additionally, the positive impact of physical activity/exercise on metabolic health depends primarily on whether it is part of structured, supervised programs rather than simply following training advice [108].

Systematic reviews, meta-analyses [109,110], and randomized controlled trials have compared the metabolic effects of aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic and resistance training in individuals with T2D or overweight/obesity. All types of supervised exercise proved more beneficial than unsupervised or no exercise [80,111]. In line with these results, Sparks et al. [112] studied the effects of a 9-month supervised program of aerobic exercise alone (150 min per week at a moderate intensity of 50–80% of VO2max), resistance exercise alone (3 days per week, including upper body, leg, and abdominal training with machines and free weights, lasting 45–50 min per session), or a combination of aerobic and resistance training, in individuals with T2D (average BMI 34.8 kg/m2, HbA1c 7.05%). The results showed that combining resistance and aerobic training improved mitochondrial function, glucose and lipid oxidation, and increased VO2max more than either method alone.

Acosta-Manzano et al. [113] compared the effects of the two most common types of resistance training: hypertrophy and muscular endurance. They evaluated the impact of their intervention on glycemic control, lipid profile, body composition, BP, inflammatory markers, and physical fitness in individuals with T2D. Both hypertrophy and muscular endurance training demonstrated similar benefits for metabolic control, indicating that these exercises can be used interchangeably based on individual preferences.

The effects of aerobic, resistance, or combined aerobic/resistance exercise on glycemia were examined in nine-month randomized controlled trials involving sedentary adults with T2D (average HbA1c 7.32%, diabetes duration about 7 years) and obesity (average BMI 34.8 kg/m2) [112,114], and in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [108,109,110,115,116]. Significant reductions in HbA1c were observed across all three exercise modalities compared with the non-exercise control groups, with combined aerobic and resistance exercise showing the most significant advantage. This can be explained by the combined increase in insulin sensitivity and GLUT-4 transporter expression resulting from aerobic and resistance training, which occurs not only in myocytes (Section 6) but also in adipocytes [117]. In the meta-analysis by Snowling and Hopkins [115], insulin sensitivity after aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic and resistance exercise in individuals with T2D increased by 28%, 12%, and 106%, respectively, as measured by HOMA, Insulin Sensitivity Index, and euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps. Notably, significant reductions in HbA1c occurred only when the training programs were supervised and structured, not when they were unsupervised or based solely on physical activity advice [108,109].

Randomized-controlled trials by Sparks et al. [112], Schroeder et al. [118], and Amare et al. [119] compared the effects of 2- and 9-month supervised programs of aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic/resistance exercise on blood lipids and body composition in adults with T2D (average HbA1c 7.05%), and obesity (average BMI 32.3 kg/m2). The exercise protocols involved 150–180 min per week and 60 min per session of aerobic training (at moderate intensity on a cycle ergometer or treadmill), resistance training (using weight machines and free weights targeting all major muscle groups), and combined aerobic and resistance training at the same intensity as the individual types but with the total time for each type and the exercises per session halved. These studies were complemented by a recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Lafontant et al. [120]. The results showed that aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic/resistance activities effectively reduced body fat mass, with the combined approach having an advantage over each exercise alone. Aerobic exercise resulted in a 1% decrease in body weight, while resistance and combined training had no significant effect. This can be explained by changes in lean body mass, which decreased by 0.66% after aerobic exercise, and increased by 6.3% and 1% after resistance and combined training, respectively, reflecting reductions in fat mass and gains in muscle mass [111].

Combined aerobic and resistance exercise was also more effective in lowering diastolic BP by four mmHg, without affecting systolic BP [118]. Other studies verify the positive impact of combined training on diastolic BP [110,111,115,121], although they demonstrate that resistance training can be more effective than other exercise modalities at lowering systolic BP [111]. Generally, regular exercise of any type is recommended for managing hypertension as it helps improve metabolic and vascular insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, reduces hyperinsulinemia, and decreases sympathetic tone and sodium reabsorption in the kidney [24]. The differences between studies may partly result from variations in BP severity—some studies include participants who are receiving treatment for hypertension—suggesting that higher BP levels might exhibit more noticeable effects of exercise [111].

Physical activity and exercise are considered primary treatments for hyperlipidemia. For lowering blood triglyceride levels, a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease, combined aerobic/resistance training is more effective than either aerobic or resistance exercise alone, compared with no-exercise controls [109,111,116,118,122,123]. The reason can be explained by the mechanisms by which muscle derives energy during aerobic exercise, which mainly depend on NEFA oxidation with a limited contribution from glucose. In contrast, during resistance exercise, energy production primarily depends on glucose oxidation, with a limited contribution from NEFA (Section 6). As a result, aerobic exercise causes a rapid, strong, and long-lasting increase in lipoprotein lipase (LPL) activity in muscle (but not in adipose tissue), which helps remove triglycerides from blood, lowering their levels. Triglycerides are then hydrolyzed to NEFA by muscle hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and oxidized to supply energy for contractions. In addition to blood-derived triglycerides, intramuscular triglycerides are also hydrolyzed by the same enzymes to supply NEFA for oxidation. All three enzymes, LPL, HSL, and ATGL, are activated by muscle contractions. The activation of LPL during resistance exercise is less pronounced than during aerobic exercise, suggesting that combining the two is more effective than either alone. It has been suggested that stimulating GLUT-4 transporters and LPL activity during exercise helps supply sufficient glucose and NEFA to the working muscle, thereby restoring glycogen and triglyceride stores that become depleted during the workout [88,124,125,126].

Degradation of VLDL by LPL in muscle produces LDL-cholesterol. It also releases surface phospholipids and apo-lipoproteins that contribute to the final transformation of HDL in blood after its production in the liver and intestine. Since VLDL breakdown depends on LPL, increasing LPL activity in muscle would likely result in more surface lipid particles being transferred to HDL in the blood, thereby increasing HDL levels. Blood LDL levels are partly regulated by the breakdown of VLDL by LPL and by the rate of LDL removal from the liver. Therefore, changes in lipoprotein levels following both aerobic and resistance exercise primarily result from local adaptations in muscle [127].

Regarding the effects of exercise on lipids, although literature has reached some consensus, the results are generally somewhat inconsistent across studies. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, Smart et al. [128] attributed the disagreements to the absence of a comprehensive synthesis of results to clarify lipid responses to various exercise types, as well as to the high heterogeneity across protocols. The results of this interesting meta-analysis showed that aerobic exercise alone and the combination of aerobic/resistance exercise are most effective at lowering triglyceride and LDL levels while increasing HDL levels. Resistance exercise alone is most effective at raising HDL levels, with a lesser effect on triglycerides and LDL. These authors [128] emphasize that the energy expenditure for each type of exercise in T2D is a key factor in altering not only lipid levels but also insulin sensitivity and glycemic control. Therefore, to compare the effectiveness of different exercise modalities, the amount, intensity, and energy expenditure should be kept similar to draw reliable conclusions; this is not always the case. Additionally, high-intensity exercise may require different adjustments in lipid or glucose use as energy sources compared to training at low or moderate intensities. This is particularly important for individuals with T2D who are overweight or obese and have significant insulin resistance and metabolic inflexibility [7,129]. These individuals lose the ability to oxidize glucose or NEFA interchangeably in muscle, depending on the type, duration, and intensity of exercise. In two systematic reviews and network meta-analyses of individuals with T2D and overweight/obesity, Pan et al. [109] and Liang et al. [111] also reported that combined resistance and aerobic training are most effective in lowering LDL. In contrast, aerobic and combined aerobic and resistance training are most effective in increasing HDL levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the effects of supervised aerobic, resistance, and combined (aerobic + resistance) exercise on HbA1c (%), adipose tissue mass (%), blood levels of lipids (mg/dL), and increase in insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR) (%) in individuals with T2D, overweight or obesity. The (−) sign indicates a decrease; the (+) sign indicates an increase. The data represent average values and were retrieved from references [109,110,111,115,116,118,119,120,122,123,128].

In this context, Kraus and colleagues [107] have raised an interesting point. These authors examined the effects of exercise intensity and volume on blood lipids in overweight or obese individuals with dyslipidemia following an 8-month protocol involving either low or high amounts of aerobic exercise (jogging or walking) at low, moderate, or high intensity. The results showed that at high levels of exercise, both in amount and intensity, triglycerides and LDL decreased by 17% and 1.5%, respectively, while HDL increased by 9.7%. In contrast, at a low amount of high-intensity exercise, these changes were less pronounced, suggesting that the improvements were associated with the amount of exercise rather than its intensity. Notably, these improvements occurred without a corresponding decrease in body weight, highlighting the independent role of exercise. Interestingly, at moderate intensity, this training decreased LDL subfractions (small dense LDL atherogenic particles) without significantly affecting blood LDL levels, suggesting that the positive effects of exercise on LDL may be more related to its size and function than to its overall quantity. These findings challenge other studies that have reported limited or negligible changes in blood LDL levels following exercise.

Among older adults, aerobic exercise has been especially effective at reducing fasting blood glucose, dyslipidemia, and systolic BP compared with other forms of exercise [109,110,112,130].

Aside from typical continuous aerobic exercise, where intensity usually does not exceed 70–75% of maximal heart rate, HIIT, which involves exercise intensity exceeding 85% of maximal heart rate, has also been used in various metabolic conditions, such as obesity, T2D, or metabolic syndrome. Serrablo-Torrejon et al. [131] reported significant reductions in blood glucose, blood pressure, and waist circumference among individuals with metabolic syndrome following HIIT; however, no effects were observed on HDL-cholesterol and triglyceride levels. Sanca-Valeriano and colleagues [132] compared the benefits of continuous moderate-intensity aerobic exercise with HIIT in overweight and obese adults, finding no difference in body weight, waist circumference, body fat percentage, or fat mass. However, HIIT showed a moderately positive effect on insulin sensitivity. A similar systematic review by De Nardi et al. [133] comparing the two exercise methods in prediabetes and T2D reported greater improvements in maximal oxygen consumption with HIIT. Still, there was no difference in blood lipids, blood pressure, BMI, and waist-to-hip ratio [133].

Mansberg et al. [134] compared HIIT alone (a 5-min warm-up followed by three sprint cycling sessions at 80–100% of peak heart rate for 20 s, with a 2-min recovery between sets, and a 5-min cool-down, 3 times per week) with HIIT combined with aerobic training (walking 10,000 steps per day for 12 weeks) in obese individuals with prediabetes (average BMI 31 kg/m2, HbA1c 5.8%). Although the most significant improvement in muscle insulin sensitivity was seen with HIIT alone (18.5%), whole-body insulin sensitivity was more significantly improved by walking (42%), followed by combined HIIT and walking (28%), and HIIT alone (17%), as measured by the Matsuda index from the OGTT. HIIT, whether performed with or without walking, increased muscle hexokinase II and GLUT-4 activity and content from muscle biopsies. Overall, these findings indicate that HIIT can be an effective training option for individuals with limited time. Consistent with these findings, three systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that HIIT boosts VO2max and improves cardiometabolic risk factors, including waist circumference, body fat, resting heart rate, BP, and fasting plasma glucose levels. It has been proven to be both practical and safe for individuals with metabolic syndrome, obesity, and CVD, offering a time-efficient alternative to moderate-intensity continuous exercise training [75,135,136,137].

Regarding flexibility and balance, compared with other exercise modalities, the evidence on health benefits in T2D is limited, making it difficult to draw solid conclusions [110].

To summarize, although differences among exercise types are small, combining aerobic and resistance training—working together through synergistic mechanisms—is more effective at improving most parameters related to insulin resistance. In fact, combining aerobic and resistance training in the same session has been identified as the most effective strategy for improving body mass, body fat, fat-free mass, blood lipids, BP, insulin sensitivity, and muscle strength in individuals with T2D and obesity, thereby substantially reducing cardiovascular risk. Nevertheless, it is essential to note that physical activity and exercise demonstrate their benefits when performed consistently and in a structured manner, rather than sporadically and unguided [123].

One final but important point to note is the significant heterogeneity among studies comparing different exercise types. This includes differences in participant cohorts regarding their characteristics and number, concurrent treatments for health issues, dietary interventions during exercise training leading to changes in body weight, variations in exercise protocols—such as type, amount, intensity, frequency, duration, inability to maintain similar energy expenditure across activity modes, exercise timing, and the relationship of training to meals—along with differences in units used for measuring outcomes in exercise protocols. Additionally, studies comparing the outcomes of various physical activities or exercises within the same population are limited [128]. These factors make it difficult to reach firm conclusions when evaluating the effects of different exercise modalities.

7. The Significant Role of Regular Physical Activity and Exercise in Metabolic Diseases

For individuals with metabolic diseases, such as metabolic syndrome, T2D, or obesity, regular exercise is a crucial part of treatment. It improves insulin sensitivity regardless of changes in body fat and weight from dietary adjustments, enhances glucose and lipid regulation, reduces chronic inflammation, and decreases the risk of cardiovascular and chronic kidney disease. It also helps relieve depression, boosts cardiorespiratory fitness, and enhances overall well-being, promoting a healthy lifestyle. Therefore, it should be prescribed in primary care as medication, regardless of body weight [137,138,139,140].

In a comprehensive article, Brinkman [141] reported that to maximize health benefits, physical activity and exercise programs should be adjusted to each individual’s unique metabolic needs and concerns. When creating personalized exercise plans for people with T2D or obesity, several factors must be considered after a detailed medical history and thorough clinical assessment:

- ▪

- Review treatment schedules, especially when using insulin and sulfonylureas, to prevent hypoglycemia during and after exercise, as increased insulin sensitivity and muscle glucose uptake can last more than 24 h post-exercise. The interaction of exercise with anti-diabetic medications like metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), and SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) should also be considered (Section 8).

- ▪

- Evaluate the presence of chronic diabetic complications, such as a history of stroke, retinopathy, autonomic neuropathy, coronary artery disease, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, peripheral neuropathy, peripheral arterial disease, and diabetic foot syndrome, when designing a training program.

- ▪

- Consider response heterogeneity, especially in people with long-standing T2D, as metabolic flexibility in utilizing glucose or NEFA in muscle during exercise can be reduced [7].

- ▪

- Consider factors such as sleep quality, exercise timing, and specific dietary issues related to carbohydrate/protein intake. Choose the appropriate type, amount, duration, and intensity of exercise to achieve the individual’s goals for optimal results. Preferences regarding exercise type and related concerns are essential for reducing dropout rates [141].

After an initial assessment and pre-exercise screening, tailoring scientific guidelines to an individual’s needs, lifestyle, and preferences sets the foundation for effective, safe, and successful exercise protocols. Education, behavioral support, and regular communication with healthcare providers to adjust the exercise dose based on progress are all essential for evaluating the follow-up plan, maintaining compliance, and achieving long-term benefits, as with any other treatment (personalized prescription). Compliance with exercise protocols has been facilitated by wearable activity monitors—such as accelerometers—that measure activity duration, number of steps, and heart rate during training. These tools have proven to be practical and helpful for setting up personalized exercise plans and tracking progress [142,143].

The “American Diabetes Association” (ADA) [142] and the “American College of Sports Medicine” (ACSM) [143,144] issued consensus statements on physical activity and exercise for T2D to reduce insulin resistance and improve metabolic control.

For youth with T2D, the ADA recommends at least 60 min of aerobic activity daily at moderate to vigorous intensity, resistance training at least 3 days a week, and limiting sedentary time. In adults with T2D, to achieve metabolic health benefits and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, it is recommended to engage in regular physical activity, minimize sedentary time, and frequently interrupt prolonged periods of sitting (every 30 min) with brief activity breaks. Structured workouts lasting at least 8 weeks can reduce HbA1c by an average of 0.66% even without altering body weight. Aerobic activities (such as brisk walking, jogging, or cycling) should be done for at least 150 min each week at a moderate intensity. Start with 10 min, then work up to at least 30 min, either daily or spread out over 3 days a week, with no more than two consecutive days without activity. For vigorous-intensity aerobic workouts, a minimum of 75 min per week (approximately 10 min daily) is recommended, with no more than two consecutive days of rest. For resistance training involving all major muscle groups—such as with weight machines or free weights—at any intensity, adults with T2D are advised to perform two to three sessions weekly to support not only metabolic health but also strength and muscle mass. For older adults, the ADA recommends flexibility and balanced training (including Yoga), two to three times a week. If exercise guidelines cannot be met, physical activities such as walking, household chores, gardening, swimming, or dancing should be encouraged. It is essential to emphasize that resistance training and muscle strengthening are crucial at all ages to preserve muscle mass and prevent sarcopenia and frailty over time [142].

The recent ACSM guidelines provided similar recommendations for T2D regarding the frequency, intensity, and mode of physical activity/exercise [143]. These guidelines summarize the evidence supporting the effects of various exercise modalities in T2D when performed regularly. Aerobic exercise improves insulin sensitivity and mitochondrial function, mainly in muscle, reduces lipids, BP, and HbA1c by an average of 0.7%, and improves cardiorespiratory fitness independently of body weight loss. Resistance exercise increases muscle mass, strength, and insulin sensitivity, while also decreasing HbA1c, BP, and lipids. Combining aerobic and resistance training can lead to greater reductions in HbA1c and improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness, as well as in all other parameters studied, compared to either modality alone. Additionally, workouts at higher intensities are more effective than those at low to moderate intensities and yield better results when conducted under supervision. HIIT can also lead to physiological and metabolic improvements and is a time-efficient modality. The various exercise modalities may yield similar improvements in insulin sensitivity and glycemic control when energy expenditure is matched. Finally, the ACSM guidelines recommend performing these activities after meals to improve metabolic control (Section 6.2).

In a meta-analysis including randomized controlled trials, Gallardo-Gomez et al. [106] examined the dose–response relationship between all types of physical activity and exercise (including mind–body workouts) and changes in HbA1c in individuals with T2D. The results showed that this relationship followed a non-linear (J-shaped) curve. The optimal amount of moderate-intensity aerobic activity for achieving the most significant reduction in HbA1c was about 244 min per week (range: 183–367 min), depending on intensity, or approximately 157 min per week of vigorous-intensity aerobic activity. The range of HbA1c reductions at these activity levels varied depending on the baseline level: for uncontrolled severe T2D, the reduction was from 1.02% to 0.66%; for uncontrolled less severe T2D, from 0.64% to 0.49%; for controlled T2D, from 0.47% to 0.40%; and for prediabetes, from 0.38% to 0.24% [106].

Although physical activity and exercise interventions support metabolic health, only 54% of people seem to follow these recommendations, with 24% sticking to specific types of activities (aerobic, anaerobic, or a combination of both) [145]. Given that many may not have time for training during the workweek, the question arises whether these interventions can be concentrated into fewer days rather than spread throughout the week. In a recent nationwide cohort study involving 350,978 individuals, Dos Santos et al. [146] reported no differences in health benefits when the recommended moderate-to-vigorous physical activity or exercise interventions were performed on weekends or spread throughout the week.

In a prospective study involving 71,893 participants from the UK Biobank, Ahmadi et al. [147] examined the dose–response relationship between short, intermittent bursts of vigorous exercise (measured by accelerometry) and mortality and CVD incidence after a 6-year follow-up. The results showed a consistent non-linear inverse relationship between vigorous aerobic physical activity and all-cause mortality and CVD. The reduced risk from vigorous activity was significantly below the current guidelines of 75 or 150 min per week; just about 20 min per week (around 3 min daily) lowered all-cause mortality and CVD risk by approximately 21%, with further reductions at an optimal dose of 60 min per week (about 8 min daily) [147].

A systematic meta-analysis by Ekelund et al. [148], including 36,383 participants, examined the relationship between sedentary time, physical activity measured via accelerometry, and all-cause mortality. Overall, the results showed that any physical activity, regardless of intensity, was linked to a lower risk of death, following a non-linear dose–response pattern. The risk of death increased linearly by up to 20% with sedentary periods of 6–9 h per day and rose further by 1.5 to 2.5 times with 9–11 h of sitting daily. The most significant reductions in mortality risk (approximately 40–50%) were observed with approximately 300 min of activities at low-light intensity, 80 min of higher-light intensity, and 24 min of moderate-to-vigorous intensity per day [148].

Brisk walking is a popular form of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, and the goal of 10,000 steps per day is believed essential for maintaining metabolic health. Lee et al. [149] measured the effects of the number and intensity of daily steps on all-cause mortality over 7 years in 17,466 older women (average age 72 years, BMI 26 kg/m2). The findings showed that, contrary to common belief, approximately 4400 steps per day were sufficient to lower all-cause mortality compared to 2700 steps per day. Interestingly, stepping intensity was not associated with lower mortality after adjusting for total daily steps. Mortality rates plateaued after 7500 steps per day, with no further reduction. Consistent with these findings, a recent meta-analysis by Ding et al. [150] indicated that walking about 7000 steps per day reduced all-cause mortality by 47% and lowered the risk for T2D and CVD by 14% and 25%, respectively, compared to 2000 steps per day. These findings offer a more realistic and achievable goal.

Although regular physical activity and exercise improve the lipid profile by increasing HDL-cholesterol and decreasing LDL-cholesterol levels, some studies have reported that exercise may not affect LDL levels in younger individuals, in those with kidney problems, or at low exercise intensities [151,152]. However, the authors believe that systematic physical activity and exercise are beneficial for reducing LDL cholesterol levels and improving the blood lipid profile. Recent systematic reviews [151,153,154] and scientific guidelines [143] have confirmed this, especially when the intervention period is extended. Therefore, regular physical activity and exercise are recommended as first-line treatments for high cholesterol and reducing cardiovascular risk [155]. The beneficial effects of systematic exercise and physical activity in T2D and obesity are highlighted in Figure 3 [73,138,156,157].

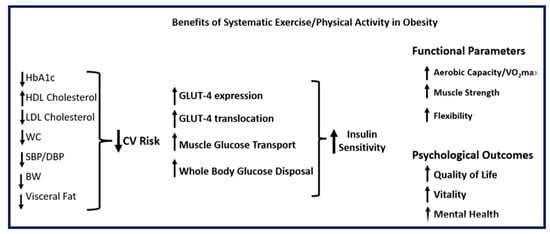

Figure 3.

Somatometric, metabolic, functional, and psychological benefits of systematic exercise and/or physical activity in obesity (BW: body weight; CV: cardiovascular; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; HDL: high density lipoprotein; LDL: low density lipoprotein; SBP: systolic blood pressure; VO2max: maximal oxygen uptake; WC: waist circumference). Upward arrows indicate an increase; downward arrows indicate a decrease.

Alongside regular sustained exercise, any form of low-intensity physical activity, whether at home or in the workplace, which involves muscular contractions and increases energy expenditure, accumulates throughout the day. This can lower plasma glucose and insulin responses, as well as metabolic risk factors, thereby reducing insulin resistance. For instance, standing engages the leg, trunk, and back muscle groups necessary for maintaining an upright position. In an interesting study, Garthwaite et al. [158] investigated the association between standing and insulin sensitivity in insulin-resistant, obese (BMI 32 kg/m2) sedentary individuals with metabolic syndrome, using euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps and accelerometers worn during waking hours. After standing for at least 2 h per day for 4 weeks, insulin resistance decreased, leading to a 3-fold increase in muscle glucose disposal. The authors [158] concluded that replacing or interrupting sitting with frequent standing breaks could improve metabolic dysfunction.

In a randomized crossover study, Dempsey et al. [159] examined sedentary overweight or obese individuals with T2D under the following eight-hour conditions: uninterrupted prolonged sitting; sitting plus 3-min bouts of light-intensity walking every 30 min; and sitting plus 3-min bouts of simple resistance activities (calf or knee raises, half-squats, and gluteal contractions) every 30 min. Two sequential mixed meals—breakfast and lunch—were administered after each intervention to estimate plasma glucose, insulin, and triglyceride responses. Interrupting prolonged sitting with frequent brief light-intensity walking or simple resistance activities decreased postprandial plasma glucose and insulin levels (area under the curve from 0 to 210 min) by 39% and 37%, respectively. Plasma triglyceride responses decreased only after simple resistance activities (65%), but not after light-intensity walking activities. The authors [159] concluded that interrupting prolonged sitting with brief bouts of simple physical activity, regardless of modality, can attenuate postprandial hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and hypertriglyceridemia in individuals with T2D. Even these minimal contraction activities can enhance muscle sensitivity to insulin by combining increases in muscle blood flow rates with the translocation and activity of GLUT-4 transporters, thus supporting previous reports [160,161,162].

Finally, in a meta-analysis summarizing 81 studies, Aune et al. [163] demonstrated an inverse dose–response association between total physical activity throughout the day (the sum of occupational, leisure-time, and walking activities, up to 5–6 h per week) and the risk of T2D.

Several reports have emphasized the superiority of physical activity over other interventions in enhancing metabolic health. For example, physical activity and exercise might be more effective than simply reducing adiposity and body weight through diet in improving insulin sensitivity and preventing cardiovascular disease. In obese, otherwise healthy subjects, Mulya et al. [164] investigated the combination of dietary intervention (administration of isocaloric high- or low-glycemic index meals) with aerobic exercise (treadmill walking or cycle ergometer at approximately 80% maximum heart rate, 5 days per week, 60 min per day) over a period of 3 months. This combination of lifestyle changes reduced body weight (8–10%) and improved insulin sensitivity in muscle (euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps), as well as the expression of genes regulating enzyme activities and mitochondrial oxidative capacity in muscle biopsy samples. Consequently, this led to improved NEFA transport and oxidation in this tissue. Notably, these effects were independent of the glycemic index or load of the diets, suggesting a more substantial contribution from exercise [164].

McAuley et al. [165] examined the combined and individual associations of adiposity measures and cardiorespiratory fitness with all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in 17,044 subjects with prediabetes followed for more than 14 years. The results showed that normal-weight fit individuals had a lower risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality compared to normal-weight unfit individuals. Interestingly, the mortality risk for fit individuals who were overweight or obese—such as those who did 30 min of moderate-intensity activity like brisk walking at least 5 days a week—was not statistically different from the control group of lean fit individuals, despite having a higher percentage of body fat and larger waist circumference. This highlights the importance of physical activity and exercise even in the presence of obesity [165]. Furthermore, in a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, Rao et al. [166] compared the effectiveness of sustained monitored exercise and pharmacological interventions used for the treatment of obesity or T2D (metformin, liraglutide, orlistat, empagliflozin) in reducing visceral adiposity in 3602 overweight or obese participants over six months. The results indicated that exercise interventions were more effective than pharmacological interventions at reducing visceral adipose tissue.

In summary, physical activity and exercise are vital components of interventions designed to prevent and treat metabolic diseases and reduce cardiovascular risk by targeting the primary pathogenic mechanism of insulin resistance. The timing, duration, intensity, and amount of aerobic (endurance) exercise, anaerobic (resistance) exercise, or a combination of both should be tailored to each individual for optimal results. In a comprehensive commentary, Arsenault and Despres [167] quoted the principle of physical activity as “some is better than none, more is better, and earlier is best.”

8. Exercise-Drug Interactions in People with T2D or Obesity

Exercise training is considered a primary treatment for metabolic diseases, mainly because it increases insulin sensitivity. Additionally, medications such as metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs), and SGLT-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) play a crucial role in managing T2D, obesity, and insulin resistance. As a result, combining these medications with physical activity and exercise programs has gained significant interest.

8.1. Metformin

Metformin is the primary medication used to treat T2D, but its effects when combined with exercise—a key therapy for metabolic diseases—are somewhat unfavorable. In this section, we present some representative studies on the combination of metformin and exercise in individuals with obesity, insulin resistance, prediabetes, or T2D.

Sharoff et al. [168] examined the effects of 14 days of metformin therapy (1000 mg twice daily) or a placebo, combined with one exercise session on a cycle ergometer (40 min at 65% VO2max), on insulin-resistant, euglycemic obese adults (average BMI 30 kg/m2). Unlike a single exercise session, the combination with metformin did not increase whole-body insulin sensitivity; instead, it increased endogenous glucose production (as assessed with euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamps with labeled glucose infusions), suggesting that metformin may reduce the effectiveness of exercise. This adverse effect can be explained, at least in part, by the increase in plasma NEFA, lactate, and glucagon concentrations that occur when metformin is combined with exercise, leading to stimulation of gluconeogenesis and increased endogenous glucose production. Alternatively, the combined dose of acute exercise and metformin might be high enough to desensitize the pathways through which exercise and metformin exert their metabolic effects. In agreement with these findings, Malin et al. [169] showed that, in contrast to supervised aerobic and resistance exercise alone (cycling for 45 min 3 days a week and resistance exercise—chest/leg press, latissimus pull-down, bicep curls, and triceps pushdowns—two sets of 12 repetitions for 2 days a week) over 12 weeks, the combination with metformin (1000 mg twice daily) did not have additive effects on risk factors for CVD (BP, HDL/LDL/triglycerides, and hsCRP) in euglycemic obese adults (average BMI 33 kg/m2) with impaired glucose tolerance (average fasting and 2 h postprandial plasma glucose 100 mg/dL and 172 mg/dL, respectively, after an OGTT). Furthermore, in euglycemic obese adolescents (average BMI 33 kg/m2) with insulin resistance (assessed by HOMA-IR), Clarson et al. [170] showed that metformin therapy (500 mg three times daily), combined with structured exercise and nutritional counseling, reduced body weight but did not improve insulin resistance.

The combination of exercise and metformin in T2D has been examined in the following studies.

In a randomized crossover study, Boule et al. [171] examined the combination of metformin (1000 mg twice daily) or placebo—each taken for 28 days—consumed with breakfast and dinner, along with one session of resistance and aerobic exercise at the end of each treatment period, in treatment-naïve obese individuals with T2D and optimal glucose control (average BMI 28.6 kg/m2, HbA1c 6.5%). Exercise sessions were performed about 3 h after breakfast. This session involved 20 maximal leg extensions and flexions on a dynamometer, followed by 35 min of treadmill walking at increasing intensity. The authors measured heart rate, respiratory exchange ratio, plasma lactate, NEFA, and glucagon levels, as well as fasting and postprandial plasma glucose levels after a standardized breakfast. During exercise, metformin increased heart rate, plasma NEFA, lactate, and glucagon levels, and increased fat oxidation. Notably, the combination of metformin with exercise was not additive and was less effective at lowering postprandial glycemia. This may be explained by increased secretion of glucagon and other counterregulatory hormones, which are known to rise during high-intensity exercise, as well as by elevated NEFA and lactate levels, which contribute to increased endogenous glucose production.