1. Introduction

Note: the term sargassum is used in this report as the common name for the Sargassum species found in the beach drift on the Turks and Caicos Islands, predominantly S. fluitans III and S. natans I and VIII.

In recent years, the Caribbean has experienced sudden inundations of seaweed masses on coastlines and beaches, predominantly of the holopelagic

Sargassum fluitans III,

Sargassum natans I and

Sargassum natans VIII [

1,

2]. Thought to originate from the Sargasso Sea, this is now acknowledged to be from the North Equatorial Recirculation Region (NERR), located off the coast of Brazil and Northwest Africa, drifting into the eastern Caribbean on currents [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

The floating sargassum rafts provide a rich habitat for many species such as sea turtle hatchlings (

Chelonioidea spp.), seahorses (

Hippocampus spp.), flying fish (

Exocoetidae spp.), more than 145 invertebrate species and at least 100 other species of fish reported to use them for forage, refuge, and breeding [

9,

10,

11]. There is little peer-reviewed evidence on what species remained when the rafts washed on to coastal shores, although there are anecdotal reports of dead fish producing an odor, and of birds feeding amongst the rotting seaweed. Researchers working in the Mexican Caribbean took samples at 2, 5 and 500 m from the shore and found high diversity and number of individuals in rafts at sea but lower abundance near the shore. This led to the suggestion that harvesting sargassum from within the reef lagoon might be less damaging than taking it from the sea, although this was caveated by the recommendation for more research to inform management decisions [

12].

There are more than 350 species of seaweed in the genus

Sargassum, and these regularly wash onto beaches in small quantities. It is only since 2011 than massive inundations have occurred, damaging local economies and the environment across the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and West Africa [

1]. This led to the United Nations producing ‘The Sargassum White Paper’, referring to “golden tides” and advising monitoring to enable understanding of the abundance and distribution of sargassum landings [

13]. This phenomenon has attracted considerable attention as a biomass resource, with commercial potential for products ranging from biochemicals, livestock feed, food, fertilizer, and fuel. However, as pointed out by Milledge and Harvey [

14], lack of knowledge of the composition and level of pollutants, combined with the unpredictability of the resource, presents considerable challenges. The warning of potential toxicity has been reiterated in the recent Sargassum Uses Guide [

15].

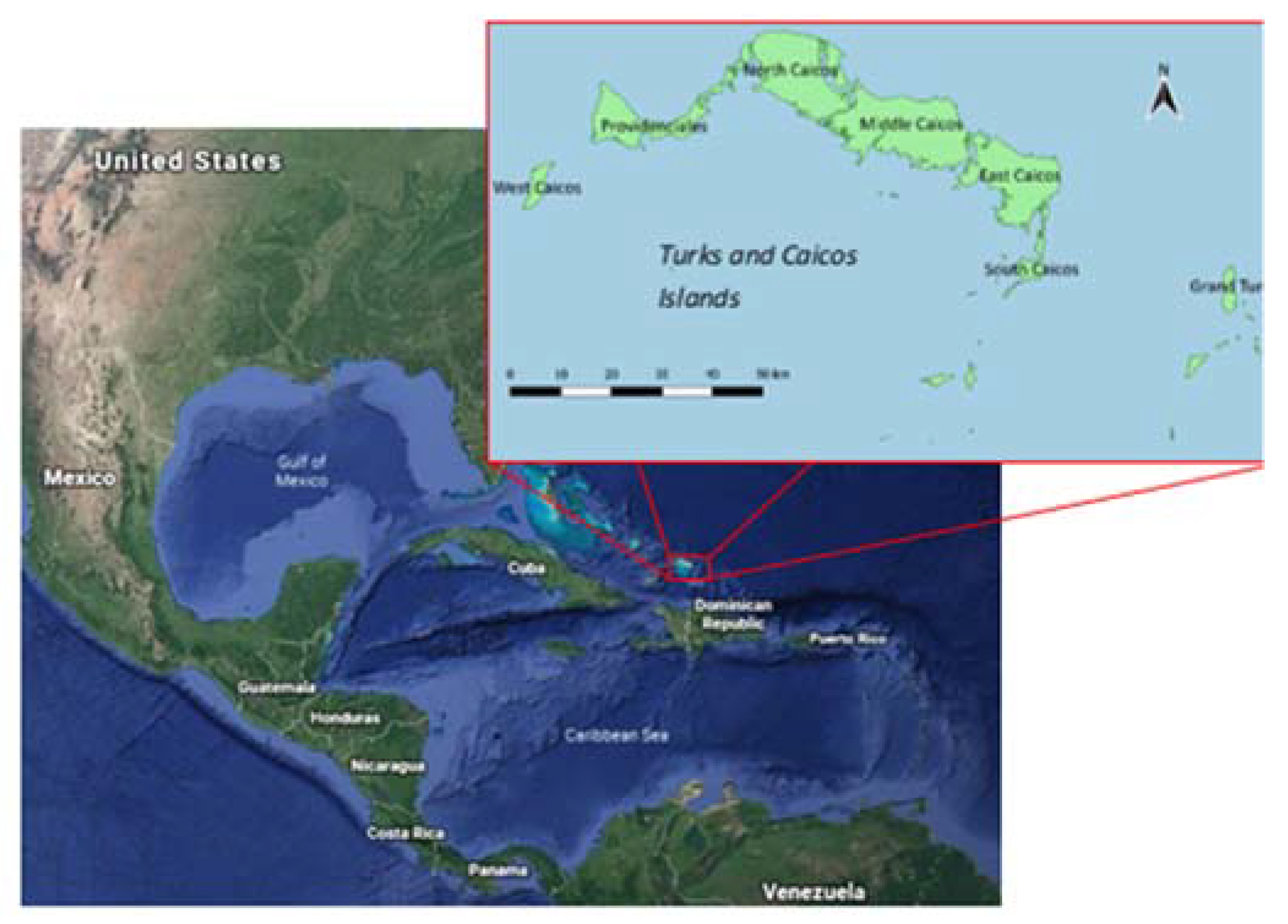

This research, part of a larger project which aimed to address these knowledge gaps, was conducted in the Turks and Caicos Islands, a British Overseas Territory comprising approximately 40 inhabited and uninhabited low limestone islands and golden sandy beaches, in the Atlantic Ocean, southeast of the Bahamas (

Figure 1).

The objective was to determine firstly what impact the sargassum was having on tourism-related businesses and secondly whether it was affecting the seagrass meadows known to be important for the economically important fisheries.

The business basis of TCI trade changed with the collapse of solar salt production and the rise of tourism in the mid-1960s, with Caribbean Islands seen as exclusive, upmarket, destinations [

16]. Providenciales rose in importance, with tourism described as the engine for economic growth [

17] and as ‘an economic revolution’ [

18]. This trend has continued, with a reported 17.5% increase in tourist arrivals in 2016, estimated at over 455,000 visitors to the archipelago, with a consequent dramatic increase in development, particularly of luxury villas and coastline beach resorts. There is a seasonal pattern, with higher numbers of visitors in winter and early spring. Brief visits, typically measured in hours rather than days, are made by cruise ships calling in to Grand Turk, the only terminal in the islands. The number of ships has increased along with their passenger capacity. Providenciales is the main island, with most resorts, and includes the most famous beach, Grace Bay. It is the gateway for tourists arriving by air, although South Caicos and Grand Turk also have small airports providing inter-island flights, with Grand Turk, to the east, having a cruise ship terminal. The key attraction is the natural environment, particularly the pale sandy beaches and turquoise blue, crystal-clear, water, and this has given rise to the phrase ‘beautiful by nature’ used in much promotional material. It is abundantly clear that the tourism industry, based on a combination of the pristine beaches and marine wildlife, is vital to the economy of the Turks and Caicos Islands.

Tourism, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, made the greatest contribution to the Gross Domestic Product, [

19], followed by the offshore banking sector and fisheries, notably Queen conch (

Strombus gigas) and spiny lobster (

Panulirus argus), which are consumed locally and exported, mostly to the United States [

20], with fishing the main economic activity on South Caicos [

21]. The same fisher fleet targets both species [

22,

23]. Historically, Queen conch (

Strombus gigas) was the principal food source, with the indigenous Lucayans and Arawak Indians using the TCI as temporary fishing platforms. The conch fishery increased after the collapse of the salt industry [

24]. The lobster fishery developed after the introduction of snorkeling and freezing technology in the 1950s and 1960s with export markets in Florida and the US driving demand, with TCI-sourced conch attracting a premium [

22].

The Caicos Bank, on the leeward side of the Turks and Caicos Islands, is shallow and sandy with vast seagrass beds consisting of

Syringodium filiforme,

Halodule wrightii and

Thalassia testudinum, the latter being dominant [

22]. These sustain the conch, lobster, and fish stocks of the TCI, providing habitat for 56 fish species, representing 22 families, at various points of their life cycle, including 8 of the 10 most abundant species landed by commercial finfish fishers [

25]. A study conducted on South Caicos found that the habitat most populated by juvenile lobsters was in East Bay and dominated by the seagrass

Thalassia testudinum with approximately 10–20% cover of the red algae

Neogoniolithon [

26]. The seagrass beds are also foraging ground for the protected hawksbill (

Eretmochelys imbricata) and green sea turtles (

Chelonia mydas), which have been harvested in TCI since at least AD 700 [

27] although this is now permitted only for domestic consumption [

28].

The tourism sector benefits from seagrass beds as they contribute to the crystal-clear turquoise waters that lure visitors to the islands. Restaurants often serve seagrass-associated species, such as conch, lobster, Nassau grouper or yellowtail snapper and snorkel and kayak tours visit seagrass meadows so tourists can encounter green sea turtles [

29]. However, the tourism industry adversely affects seagrass beds through dredging for ports, marinas and shipping channels, chemical run-off from hotels, use of motorboats and clearance of inshore seagrass to provide guests with a sandy substrate [

25].

This study investigated the effects of sargassum on tourism-related businesses and seagrass beds, which are known to support the principal economic sectors of the Turks and Caicos Islands. The first aim was to determine how strongly tourism-related businesses were affected by sargassum inundations and if the impacts varied between islands and between different business types. The second aim was to measure the sargassum accumulations on beaches on South Caicos and Middle Creek Cay and monitor the adjacent seagrass beds to determine if seagrass cover was lost and what type of substrate replaced the lost seagrass. This paper describes the results of the first stage of a larger investigation to address some of the gaps in information necessary to identify and evaluate potential sustainable solutions to the Sargassum inundation, supported by DEFRA Darwin Plus grant number DPR7P\100059.

2. Method

This section will first describe the method used to determine the views of local stakeholders and tourism-related businesses regarding the impact of sargassum and secondly the investigation into the inshore sea grass meadows.

2.1. Stakeholder/Tourist Business Interviews

Research into the views of local stakeholders, particularly businesses associated with tourism, was carried out during a visit to TCI in June 2019. It comprised face-to-face interviews and focus groups and was conducted on Providenciales, South Caicos and Grand Turk, the three islands with most tourist activity. This combined approach was selected as personal interaction is generally a more effective method of engagement than paper survey [

30] and, as time was limited, bringing people together in focus groups effectively increased the number of businesses and stakeholders reached with the additional advantage of providing deeper and richer content through interactions and group dynamics which can be particularly informative when there are differing perspectives [

31,

32]. A framework, serving as the schedule for both the focus groups and semi-structured interviews, was devised in consultation with local partners from both the Department for the Environment and Coastal Resources (DECR) and the School for Field Studies (SFS), based on South Caicos, to ensure questions were relevant and locally appropriate. The questions, with the rationale for each one, are given in

Table 1.

The focus groups were advertised by DECR on their website and on posters displayed in places frequented by tourism-related business operatives. The meetings were hosted by DECR in their offices on Providenciales and South Caicos, by the National Museum on Grand Turk, and the Sustainable Tourism Association, again on Providenciales.

All meetings began with the two MSc students from the University of Greenwich, who were acting as research assistants, presenting desk study research they had done into sargassum prior to visiting TCI. This included an overview of the sargassum issue across the Caribbean region and information on the ecology and species associated with the floating rafts to provide a context for this research.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted face to face with individual businesses identified from advertisements and publicity material aimed at tourists. These were visited and the interviewer recorded responses on a pre-prepared form, based on the questions in

Table 1, with any additional information and the business type noted. Where possible, potential respondents were phoned in advance and an appointment made; those operating from shops or beach-side locations were approached directly but given the option for the interviewer to return at a more convenient time.

2.2. Data Analysis

Focus group discussions were transcribed, and the content analyzed thematically. Differences in the views of participants on different Islands were identified, as well as themes emerging for TCI as a whole.

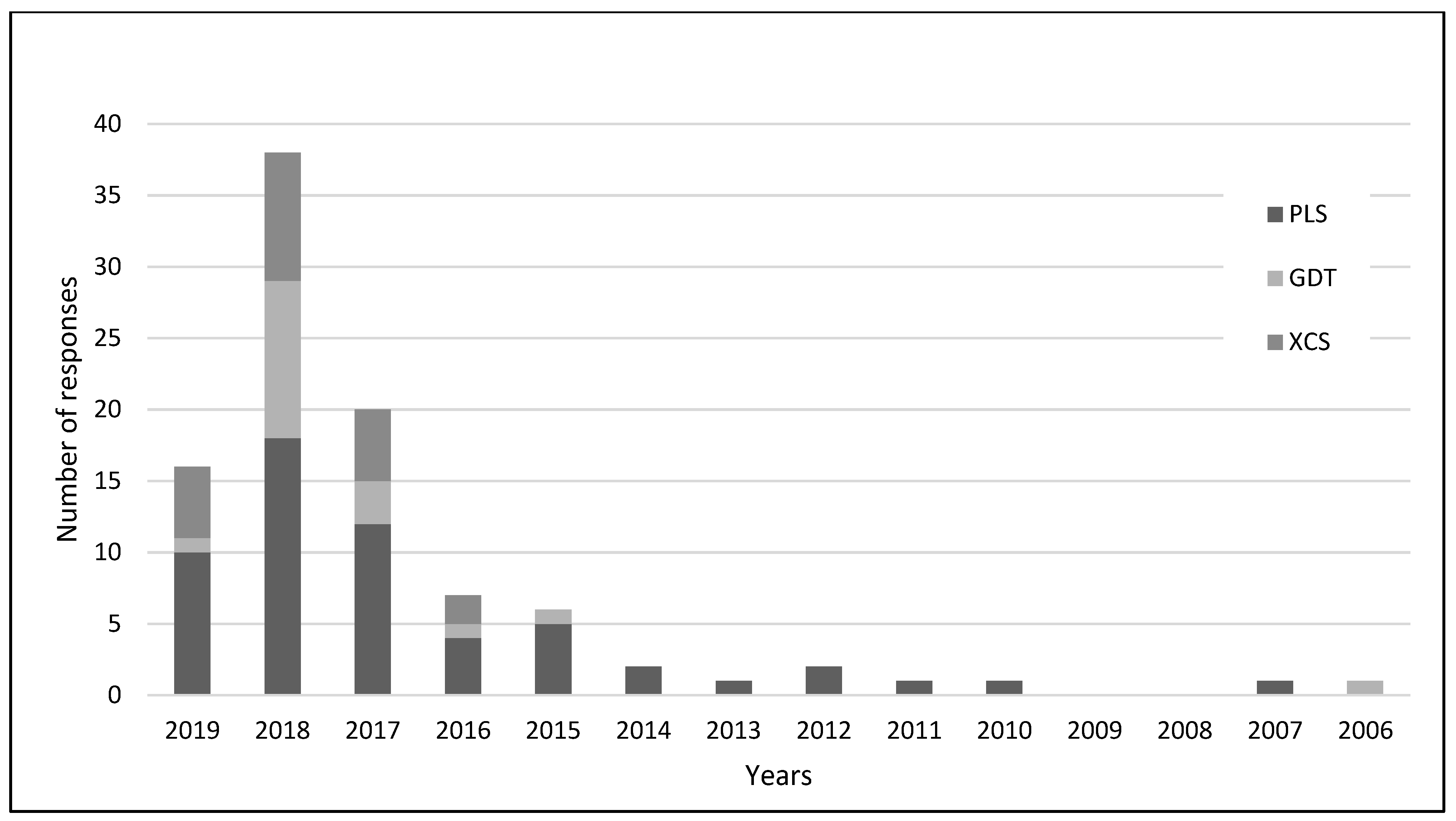

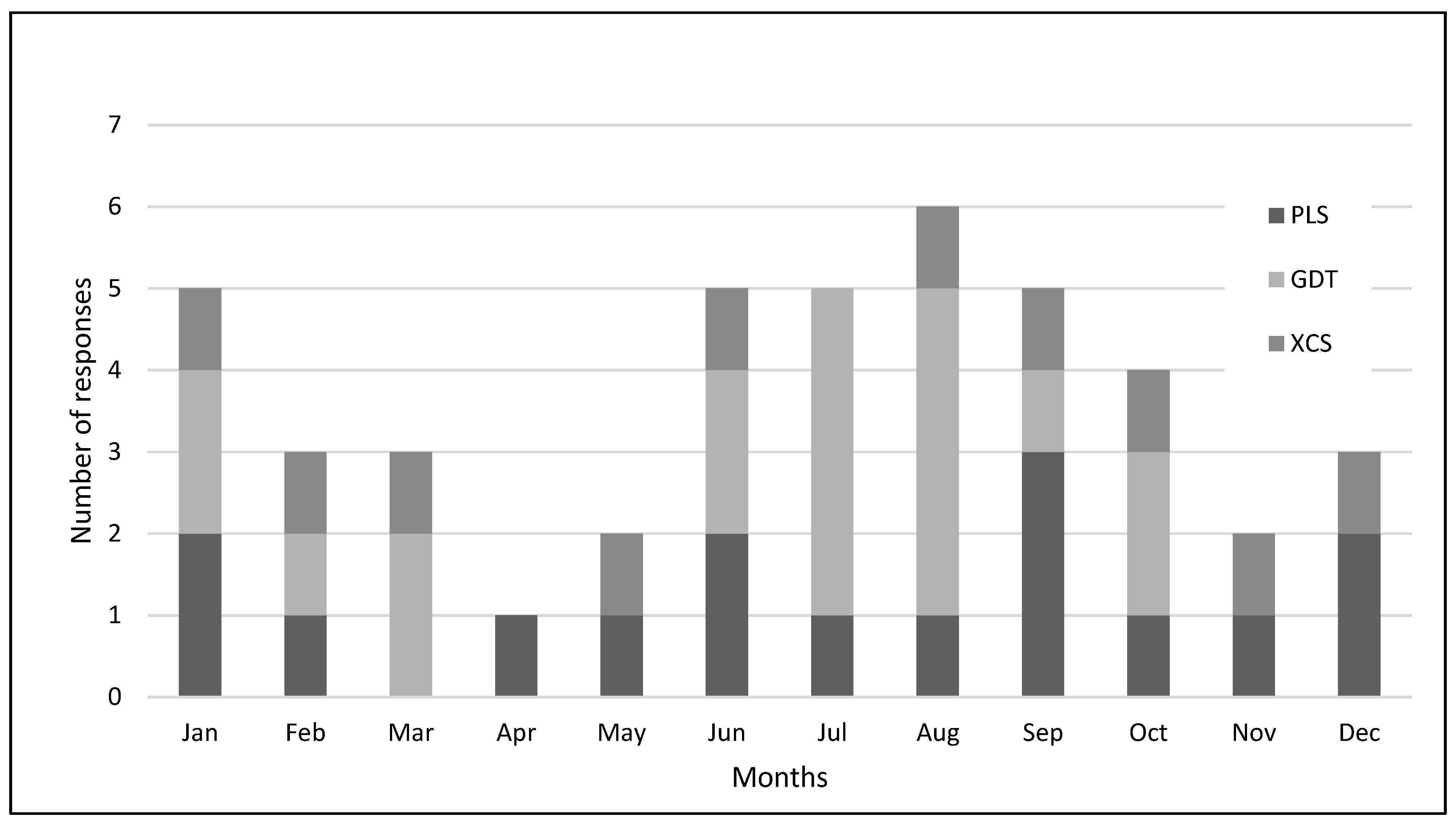

Interview responses were input into an excel spreadsheet and countif(s) functions used to enable extraction of specific criteria and used if there was more than one condition being analyzed. Some analysis was split by island and/or business type to enable interpretation using tables and graphs.

2.3. Sargassum and Seagrass Surveys

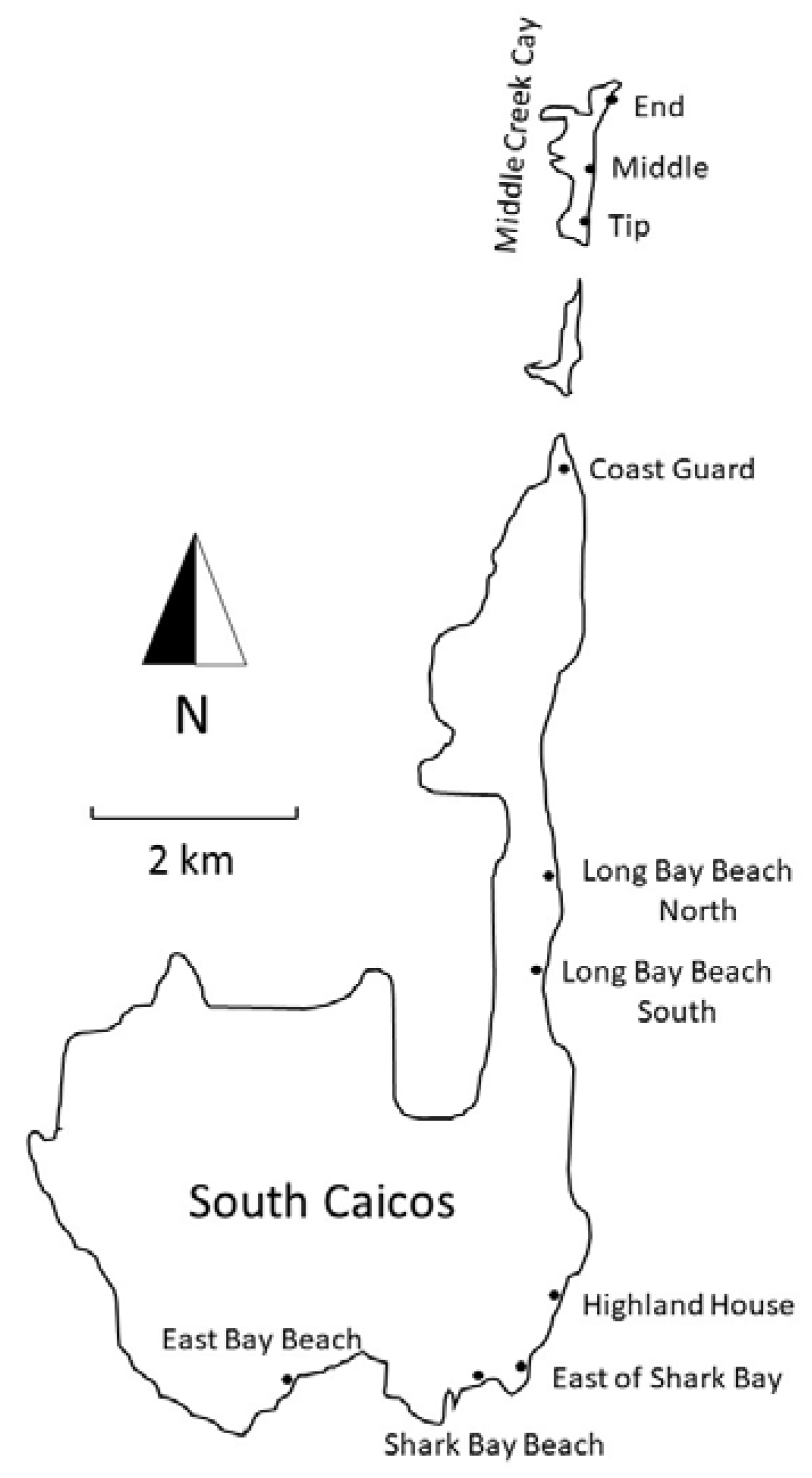

Ten beach sites were surveyed for seagrass and sargassum coverage, East Bay Beach, Coast Guard, Shark Bay Beach, East of Shark Bayt, Long Bay Beach North, Long Bay Beach South, and Highland House, all on the windward side of South Caicos Island, and the beaches at the End, Middle, and Tip of Middle Creek Cay, just north of the South Caicos peninsula (

Figure 2). All these sites consisted of sandy beaches, with sand plain, algal plain, patch reefs, rock, or seagrass beds in the shallow water, typically less than 3 m deep.

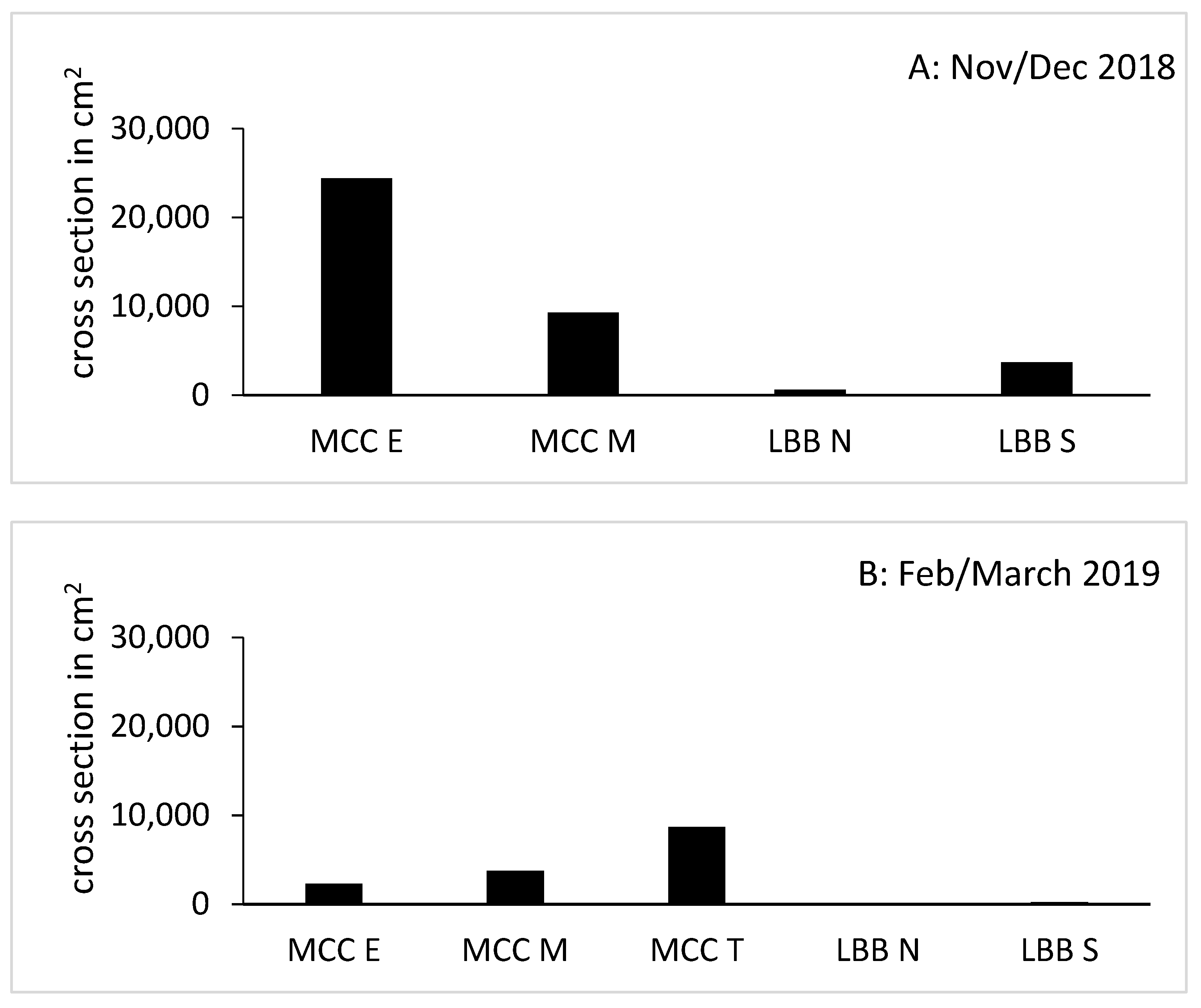

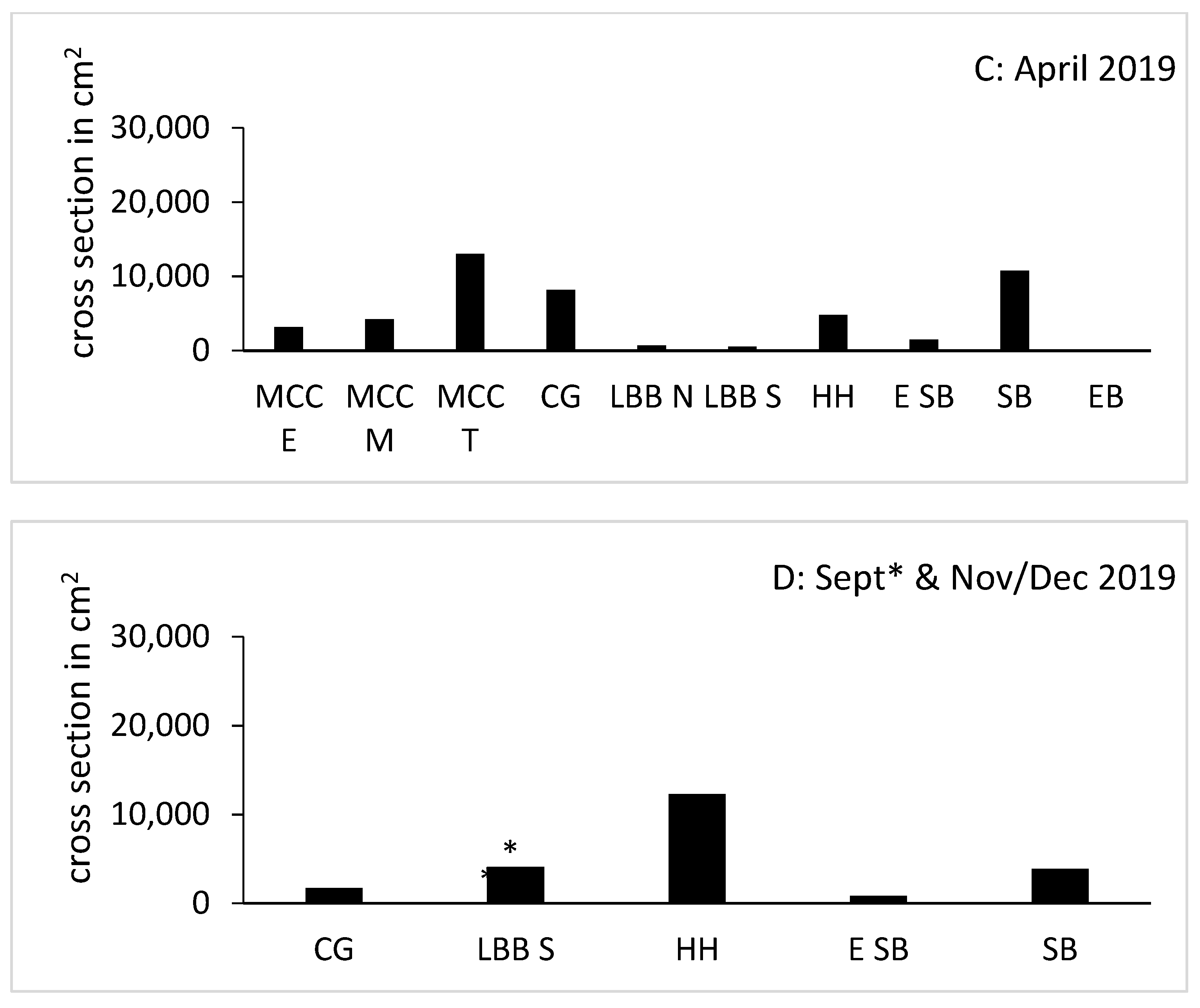

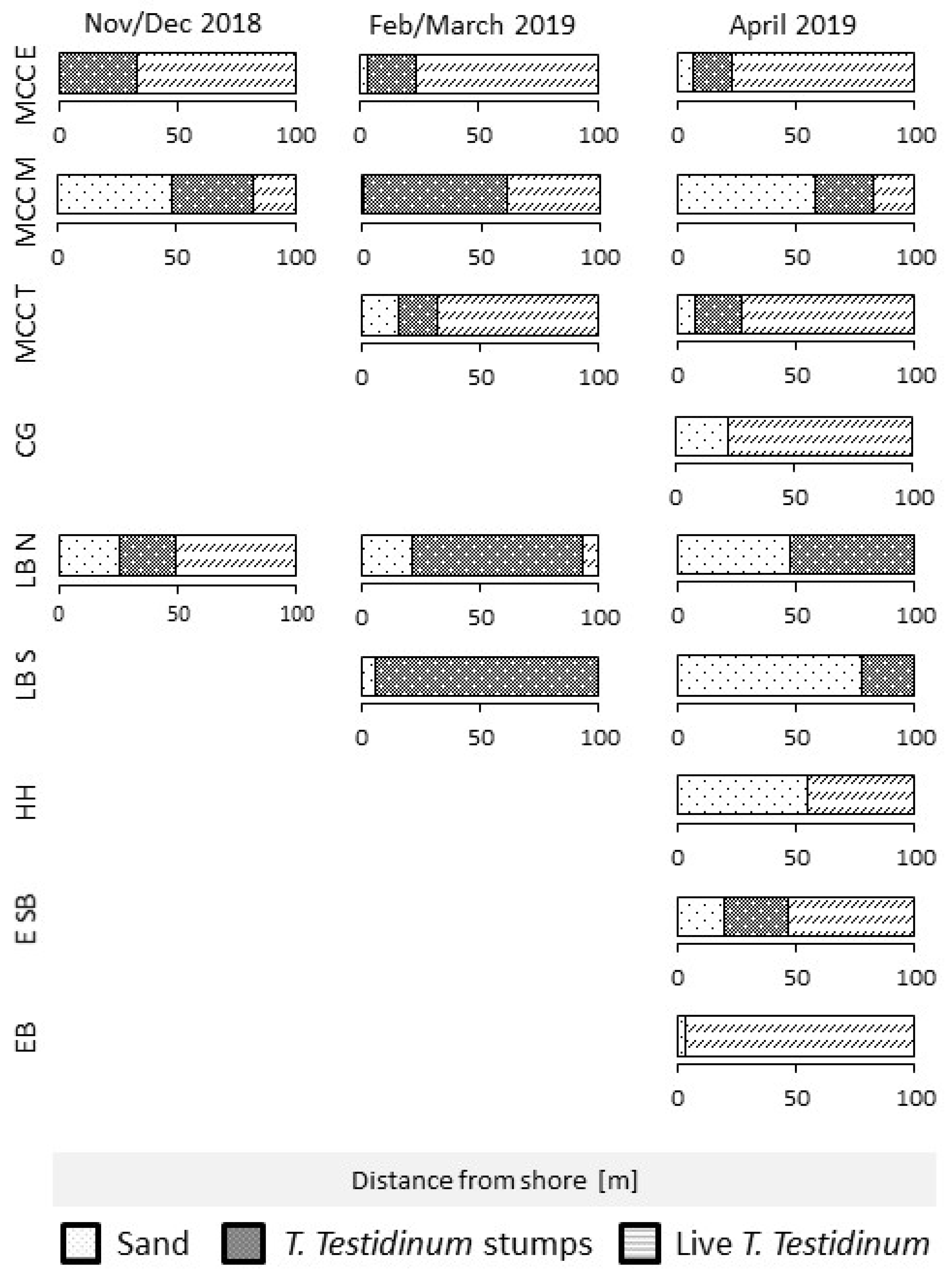

In November and December 2018, Middle Creek Cay End and Middle as well as the two Long Bay Beach sites were monitored and large areas covered in dense stumps of the seagrass species

T. testudinum were found, indicating recent loss of seagrass beds. These sites as well as Middle Creek Cay Tip were monitored again in February and March of 2019. In April 2019, a large effort was put in place to monitor all accessible eastward facing beaches on South Caicos and Middle Creek Cay (

Table 2). This effort was replicated in November and December; however, the two beaches that are regularly cleaned were not included in the surveys at that time.

If sargassum was present on the beach, a transect was walked, placing the weighted end of the line at the start of the pile (or row) of beached material closest to the water’s edge, and then pulling the line perpendicular to the water until the end of the pile. The depth of the sargassum deposit was determined by digging through it until sand was reached and the transect line placed inside it. At the 0.5 m mark and at each 1 m mark on the transect line, the depth was measured in cm. This enabled the cross-sectional area to be calculated using the following formulas:

hx = measured height of Sargassum at the 1 m mark x, and

n = last 1 m mark that had Sargassum below it.

Pictures of the beaches were taken using a Galaxy S8 Active smart phone, a Sealife DC2000 underwater camera, and a GoPro.

2.4. Seagrass Cover

The distribution of seagrass habitat was mapped by snorkeling three separate 100 m long transects perpendicular to the shore and 5 m apart from each other at each of the 10 sites. The surveyor swam along these lines, noting at each 1 m the dominant substrate: sand, living and dead seagrass. Results were recorded graphically, and photographs were taken at the sites of the Sargassum on the beach.