Everyday Streets, Everyday Spatial Justice: A Bottom-Up Approach to Urbanism in Belfast

Abstract

1. Introduction: Everyday Architecture and Spatial Justice in Belfast

2. Theoretical Framework: Everyday Architecture as a Tool for Spatial Justice

2.1. Everyday Architecture

2.2. Spatial Justice

2.3. Bridging the Two

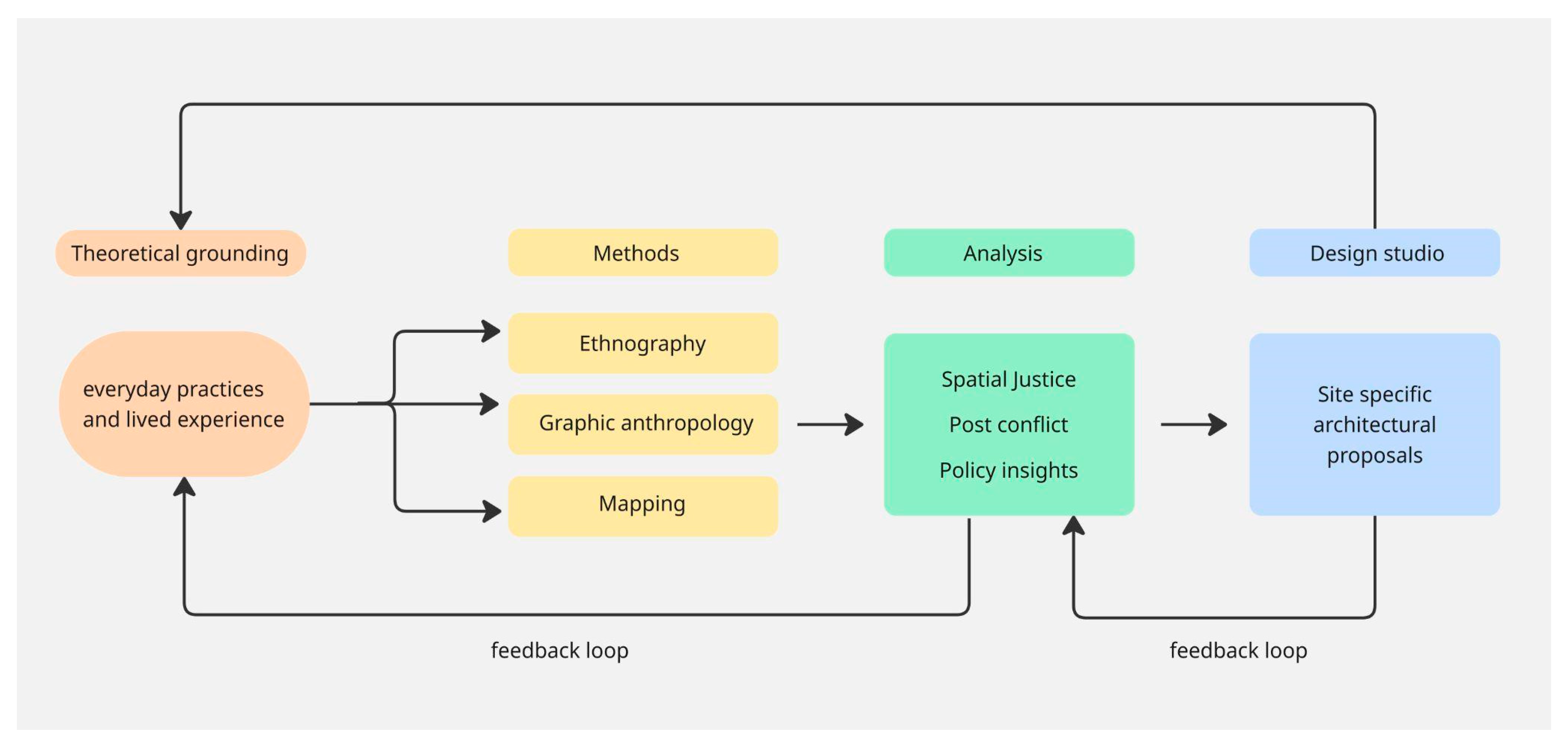

3. Methodology: Ethnography and Participatory Design as Pedagogical Practice

3.1. Ethnographic Grounding

3.2. Participatory Design Process

3.3. Pedagogical Innovation

4. Case Study: StreetSpace Studio, Belfast (2015–2025)

4.1. Studio Structure: A Yearly Cycle of Engagement and Design

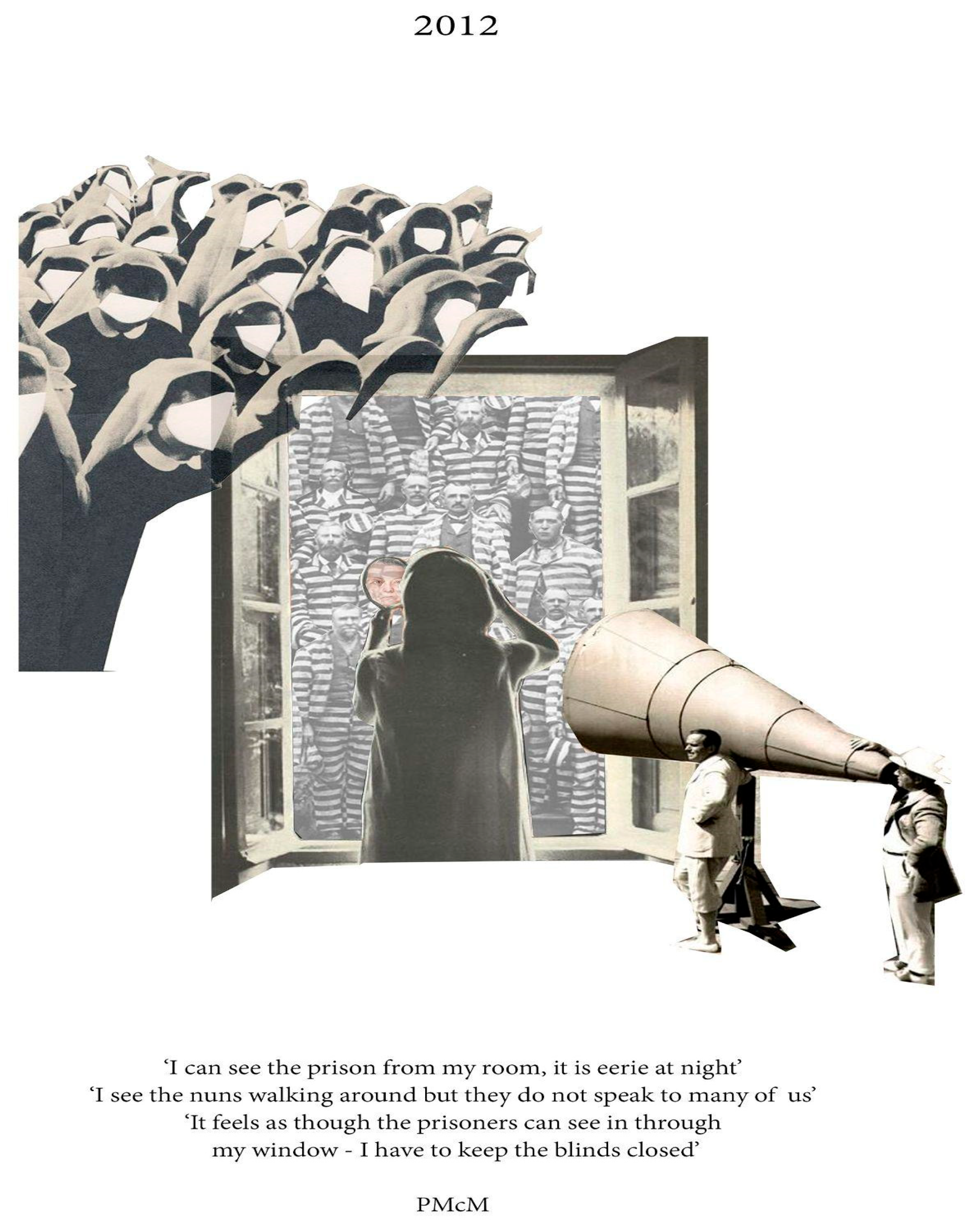

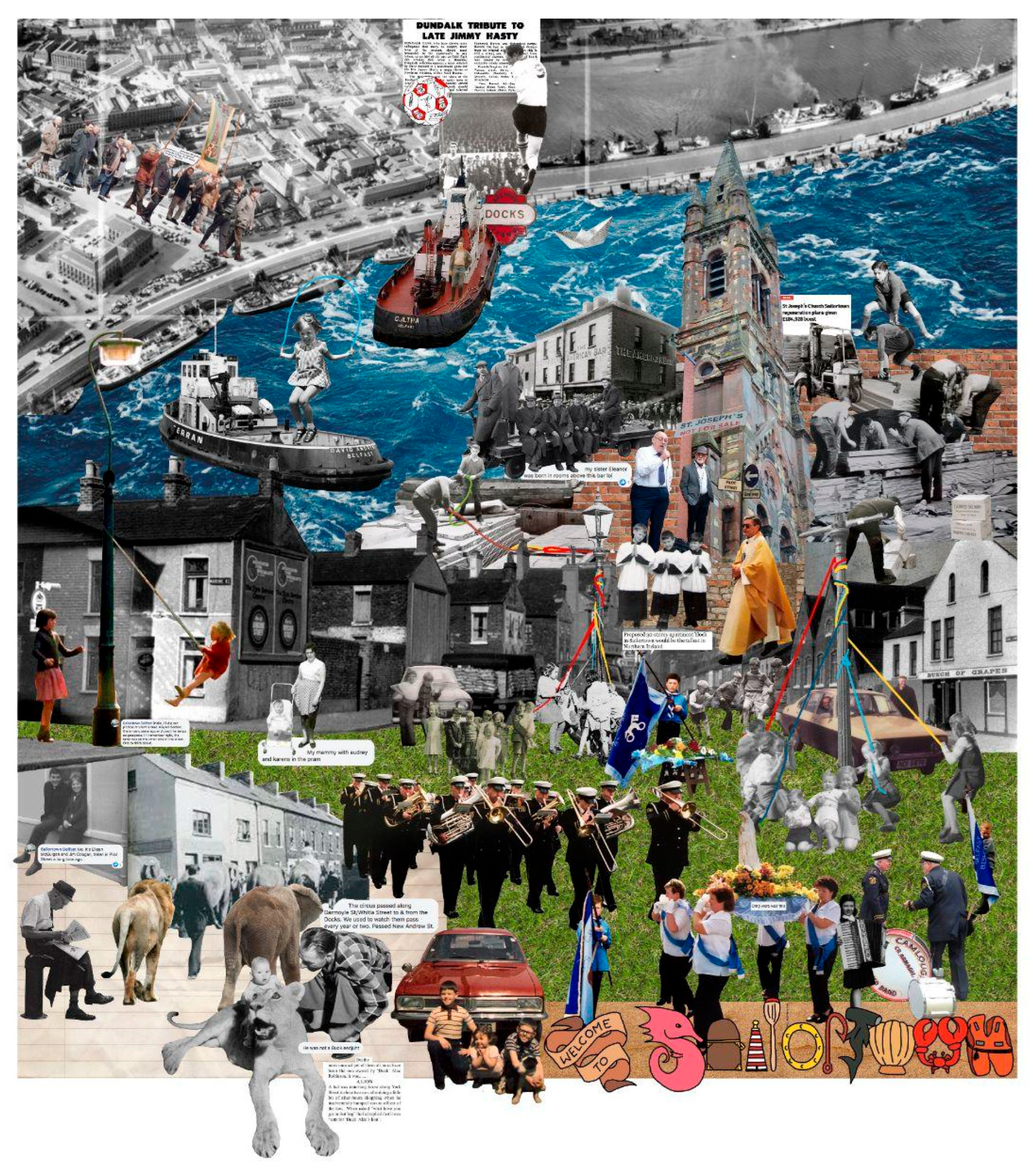

4.2. The Street as a Pedagogical and Civic Arena in Belfast

4.3. Core Themes: Everyday Streets and Urban Inclusion

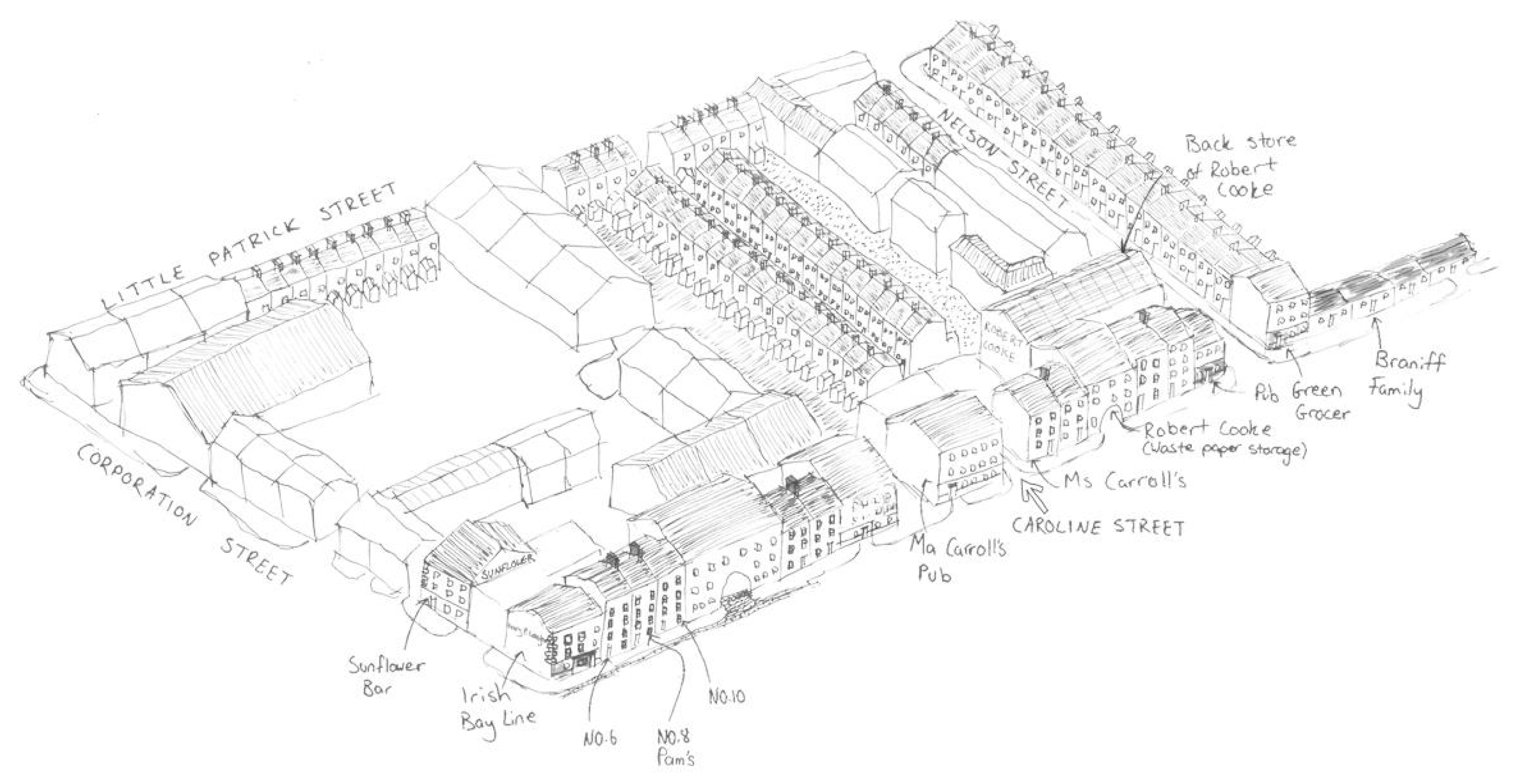

4.4. Modes of Inquiry: Research Through Design

- Quantitative mapping, such as pedestrian counts and vacancy surveys.

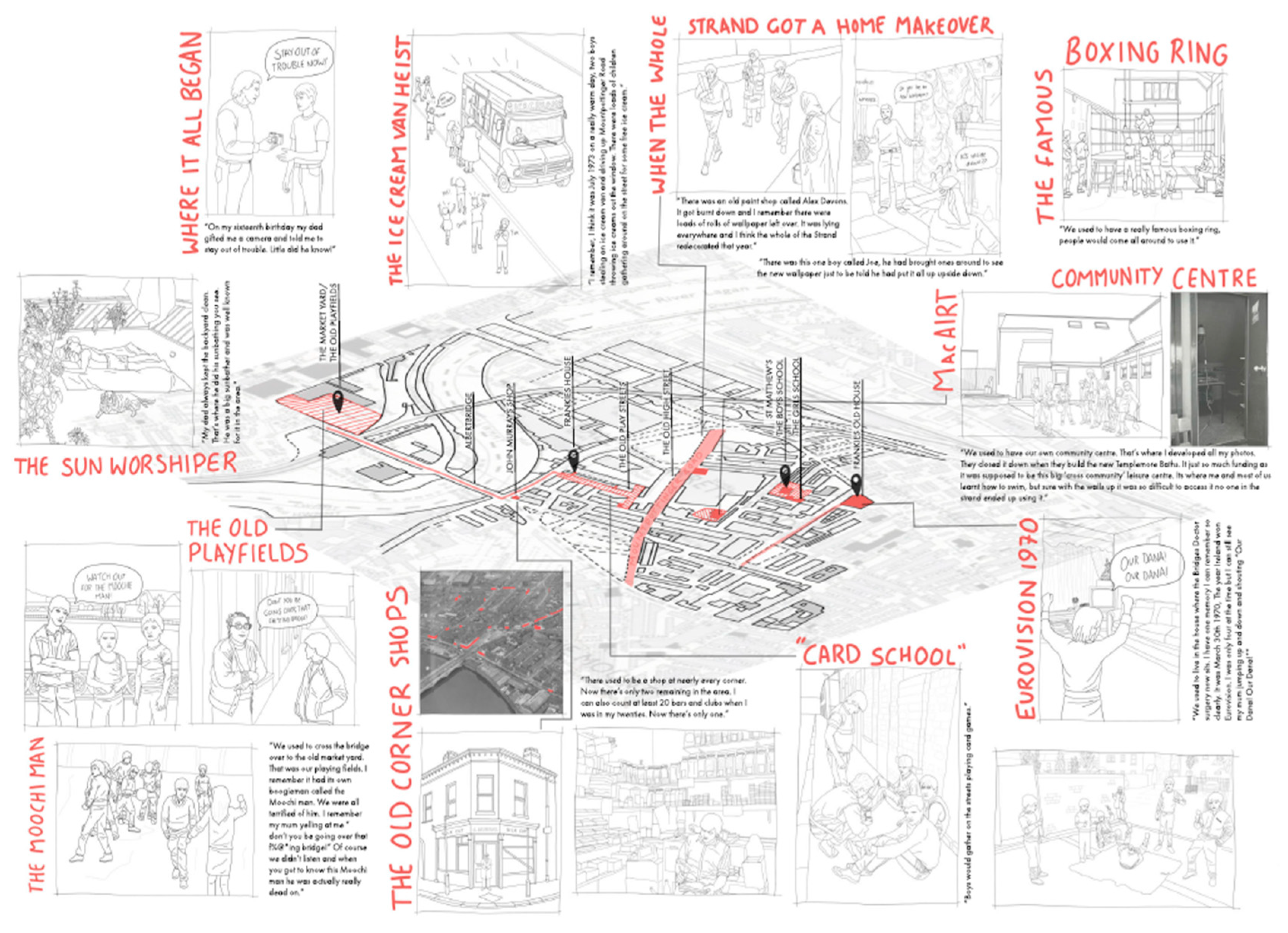

- Qualitative ethnography, including walking interviews and oral histories.

- Graphic anthropology, using drawing and diagramming to visualise socio-spatial patterns.

- Participatory workshops and co-design sessions with community groups.

- Comparative fieldwork in other cities (Ljubljana, Naples, London, Delft, Porto).

- Reflective dissemination, including interim feedback and final presentation of findings, at times in the form of a meeting, an exhibition, or publication.

4.5. Case Studies: Evidence of a Bottom-Up Urbanism

5. Discussion: Speculative Urban Futures: The Studio as a Site of Civic Transformation

5.1. Social and Ecological Dimensions

5.2. Pedagogical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Tensions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VAWG | Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls in Public Spaces |

| PPR | Participation and the Practice of Rights |

| DfI | Department for Infrastructure |

| DfC | Department for Communities |

| NIHE | Northern Ireland Housing Executive |

References

- Relph, E.C. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, J.; Rooksby, E. (Eds.) Habitus: A Sense of Place, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, P.; Kitchin, R.; Valentine, G. (Eds.) Key Thinkers on Space and Place; Sage: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Sennett, R. The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. The Global City: New York, London, Tokyo; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Flood, N. Drawing on Thick Descriptions in Architectural Pedagogy. Ir. J. Anthropol. 2019, 22, 328–335. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson, L.; Stone, S. (Eds.) Emerging Practices in Architectural Pedagogy: Accommodating an Uncertain Future; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clossick, J.; Khonsari, T.; Stevens, U. Living labs: Epistemic modelling, temporariness and land value. Build. Cities 2025, 6, 841–861, ISSN 2632-6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaijima, M.; Stalder, L.; Iseki, Y.; Ferrari, S.; Ito, T.; Kalpakci, A. (Eds.) Architectural Ethnography; TOTO Publishing: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stender, M.; Bech-Danielsen, C.; Hagen, A.L.; Kobi, M.; Zhou, Y. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Architecture and Anthropology: Contemporary Approaches to a Cross-Disciplinary Field, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, A.; Hausleitner, B.; Clossick, J. (Eds.) Everyday Streets: Inclusive Approaches to Understanding and Designing Streets; UCL Press: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Purohit, R.; Samuel, F.; Brennan, J.; Farrelly, L.; Golden, S.; McVicar, M. Improving Neighbourhood Quality of Life Through Effective Consultation Processes in the UK. Cities Health 2024, 8, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Boling, E.; Brown, J.B.; Corazzo, J.; Gray, C.M.; Lotz, N. Studio Properties: A Field Guide to Design Education; Bloomsbury Visual Arts: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sterrett, K.; Hackett, M.; Hill, D. The Social Consequences of Broken Urban Structures: A Case Study of Belfast. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 21, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyles, D.; Hamber, B.; Grant, A. Hidden Barriers and Divisive Architecture: The Role of ‘Everyday Space’ in Conflict and Peacebuilding in Belfast. J. Urban Aff. 2021, 45, 1057–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martire, A. Walking the Street: No More Motorways for Belfast. Spaces Flows 2017, 8, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S. Doing Visual Ethnography; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R. The Discipline of Tracing in Architectural Drawing. In The Materiality of Writing; Johannessen, C., van Leeuwen, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 116–137. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, A.; Ramos, M.J. Drawing Close: On Visual Engagements in Fieldwork, Drawing Workshops and the Anthropological Imagination. Vis. Ethnogr. 2016, 5, 135–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kuschnir, K. Ethnographic Drawing: Eleven Benefits of Using a Sketchbook for Fieldwork. Vis. Ethnogr. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clossick, J. Finding Depth. In Proceedings of the Mediated City Conference, London, UK, 1–3 April 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Certeau, M. The Practice of Everyday Life; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1991; (orig. pub. 1974). [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Modern Library: New York, NY, USA, 1993; First publish in 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. For Space; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Space, Place and Gender; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kalms, N. She City: Designing Out Women’s Inequity in Cities; Bloomsbury Visual Arts: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-350-15307-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rocco, R.; Silvestre, G. (Eds.) Insurgent Planning Practice; Agenda Publishing: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, P. The Battle for the High Street: Retail, Gentrification, Class and Disgust; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, B. Urban Segregation and Community Initiatives in Northern Ireland. Community Dev. J. 1999, 34, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, N.; Gregory, I. Hard to Miss, Easy to Blame? Peacelines, Interfaces and Political Deaths in Belfast During the Troubles. Political Geogr. 2014, 40, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffikin, F.; Morrissey, M. Planning in Divided Cities: Collaborative Shaping of Contested Space; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, G.; McKay, S. City Management Profile: Belfast. Cities 2000, 17, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalms, N. Hypersexual City: The Provocation of Soft-Core Urbanism; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, L. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World; Verso: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism; South End Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Feminism Is for Everybody: Passionate Politics; South End Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. Thick Description. In The Interpretation of Cultures; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R. Drawing Parallels: Knowledge Production in Axonometric, Isometric and Oblique Drawings; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, M. On Graphic Intent: A Perambulation. In Drawing Heritage(s); CIDEHUS—University of Évora: Évora, Portugal, 2021; pp. 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, S. The Just City; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, F. Why Architects Matter: Evidencing and Communicating the Value of Architects; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martire, A.; Quigley, M. Ken Sterrett: Insurgent Urbanism in Belfast’s Times of Trouble. In Insurgent Planning Practice; Rocco, R., Silvestre, G., Eds.; Agenda Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, M. Driving the social divide: Planning in Belfast reinforces the city’s segregation. Archit. Rev. Issue 2019, 1462. [Google Scholar]

- Mackel, C. Within 2000m; Irish Architecture Foundation Project 20×20: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield, D. The Agency of Small Things. In Everyday Streets; UCL Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Martire, A.; Skoura, A. Heritage, Gentrification and Resistance in the Neoliberal City; Hammami, F., Jewesbury, D., Valli, C., Eds.; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Martire, A. Street Space Studio: Architecture Learns Anthropology. Ir. J. Anthropol. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Boys, J. Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment; “Women and Public Space” in Matrix, Ed.; Pluto Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Criado Perez, C. Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men; Chatto & Windus: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.; O’Kane, N.; Garcia, L.; McAlister, S.; Cleland, C.; Bryan, D.; Martire, A.; Hunter, R. Safer Streets, Shared Voices: Insights from Public Workshops on Preventing Violence Against Women and Girls in Outdoor Public Spaces in Belfast; Queen’s University Belfast: Belfast, Ireland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Martire, A.; McGee, A.; Madden, A. Everyday Streets, Everyday Spatial Justice: A Bottom-Up Approach to Urbanism in Belfast. Architecture 2026, 6, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture6010022

Martire A, McGee A, Madden A. Everyday Streets, Everyday Spatial Justice: A Bottom-Up Approach to Urbanism in Belfast. Architecture. 2026; 6(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture6010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartire, Agustina, Aoife McGee, and Aisling Madden. 2026. "Everyday Streets, Everyday Spatial Justice: A Bottom-Up Approach to Urbanism in Belfast" Architecture 6, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture6010022

APA StyleMartire, A., McGee, A., & Madden, A. (2026). Everyday Streets, Everyday Spatial Justice: A Bottom-Up Approach to Urbanism in Belfast. Architecture, 6(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture6010022