Optimizing Cancer Care Environments: Integrating Indoor Air Quality, Daylight, Greenery, and Materials Through Biophilic and Evidence-Based Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Research Methodology

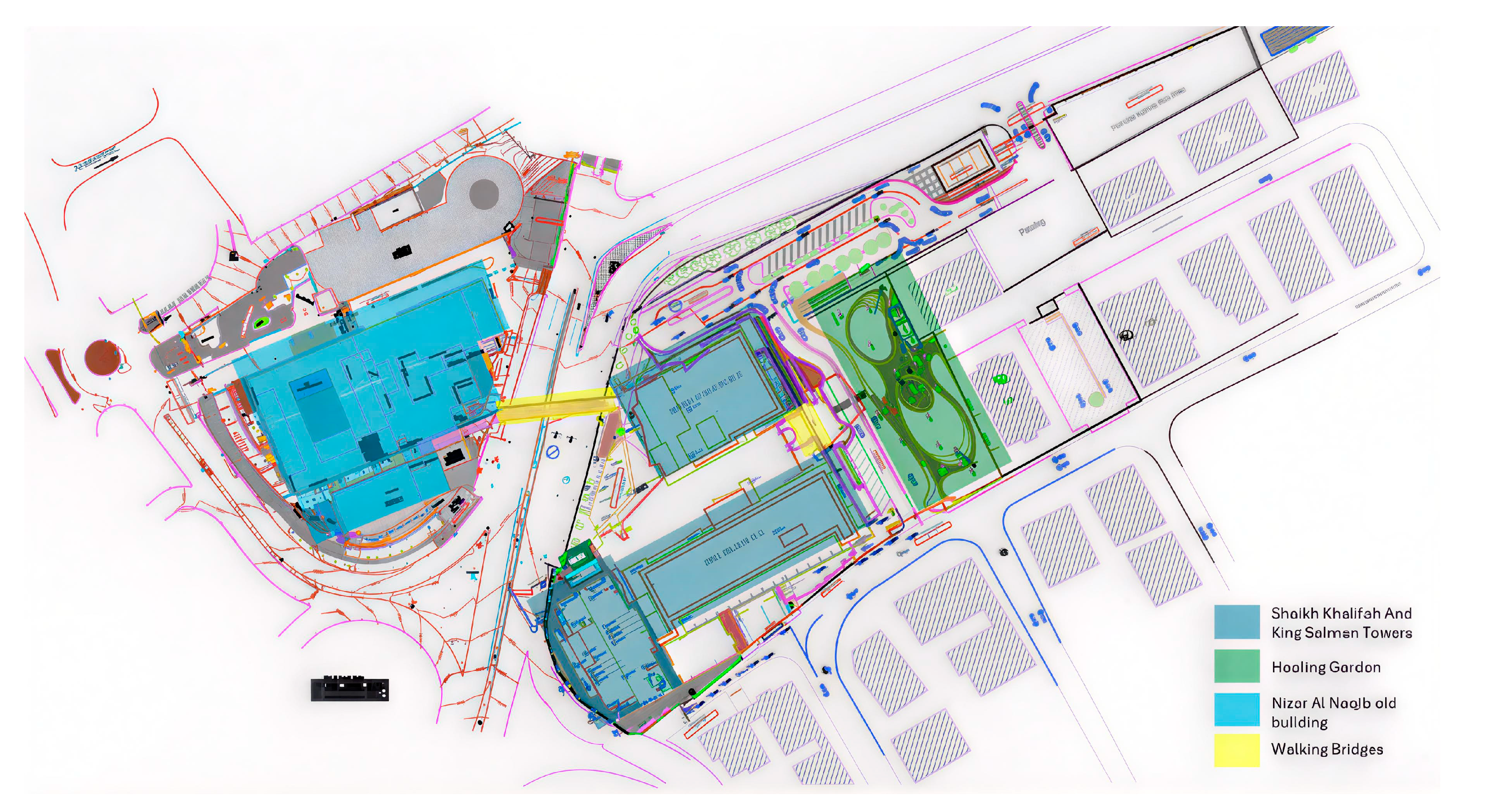

Study Setting

4. Results

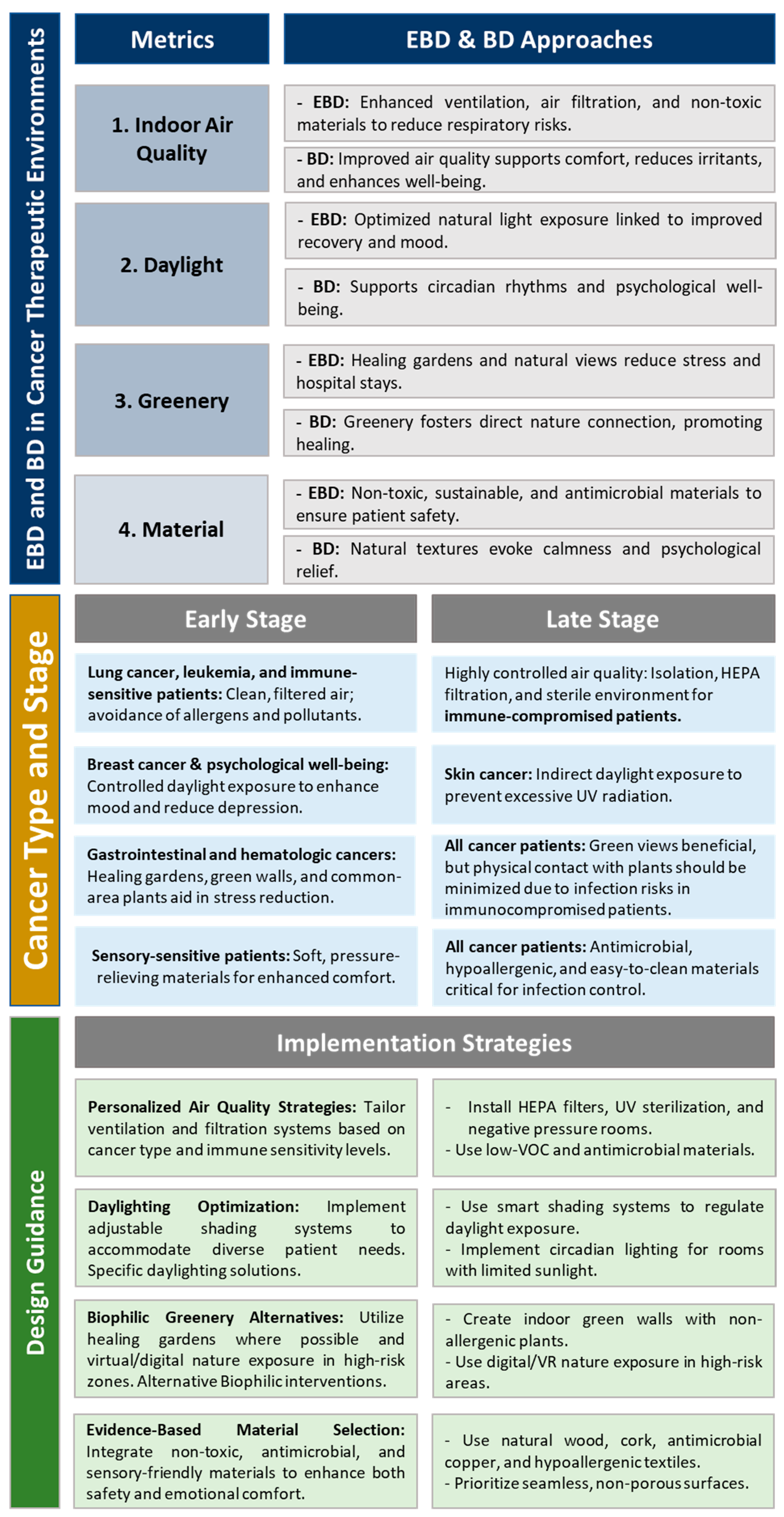

4.1. Analytical Study

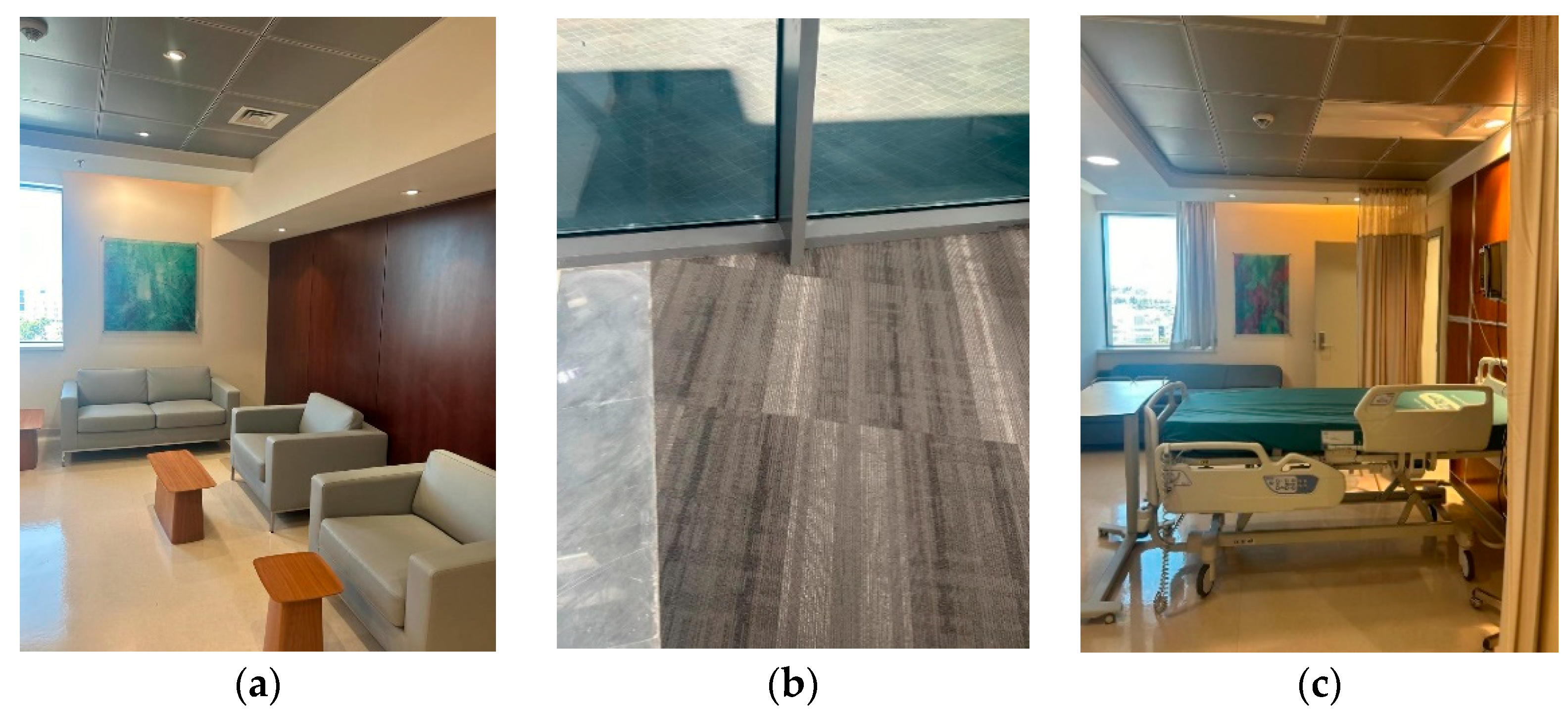

4.2. Case Study: KHCC

4.3. Observation and Semi-Structured Interviews with Architects, Oncology Healthcare Providers, and Hospital Designers

4.3.1. Indoor Air Quality (IAQ)

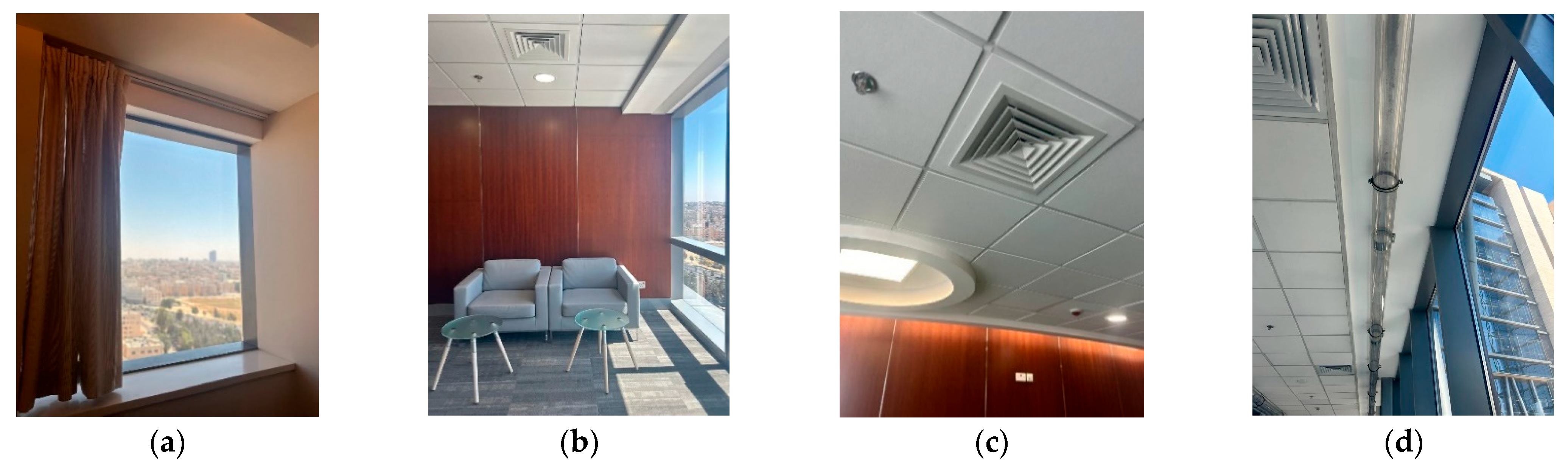

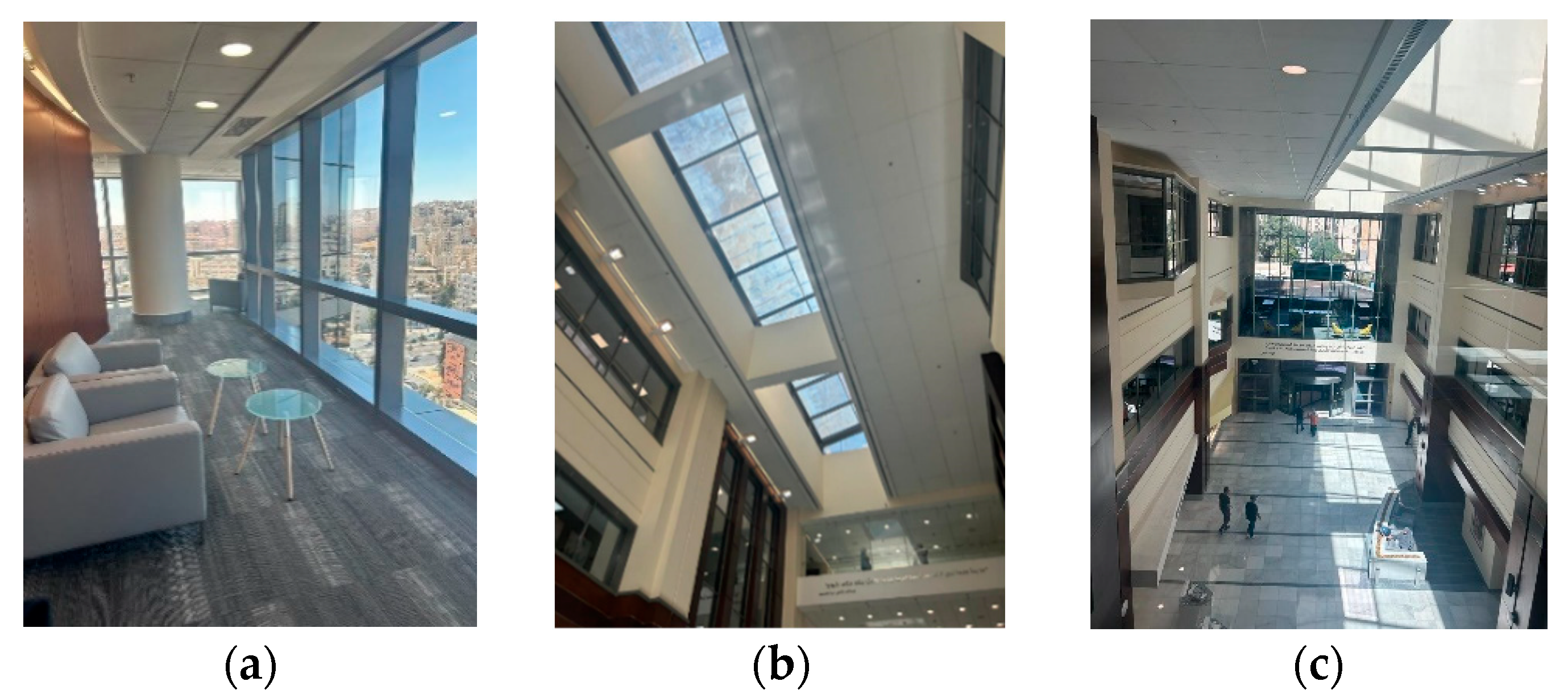

4.3.2. Daylight

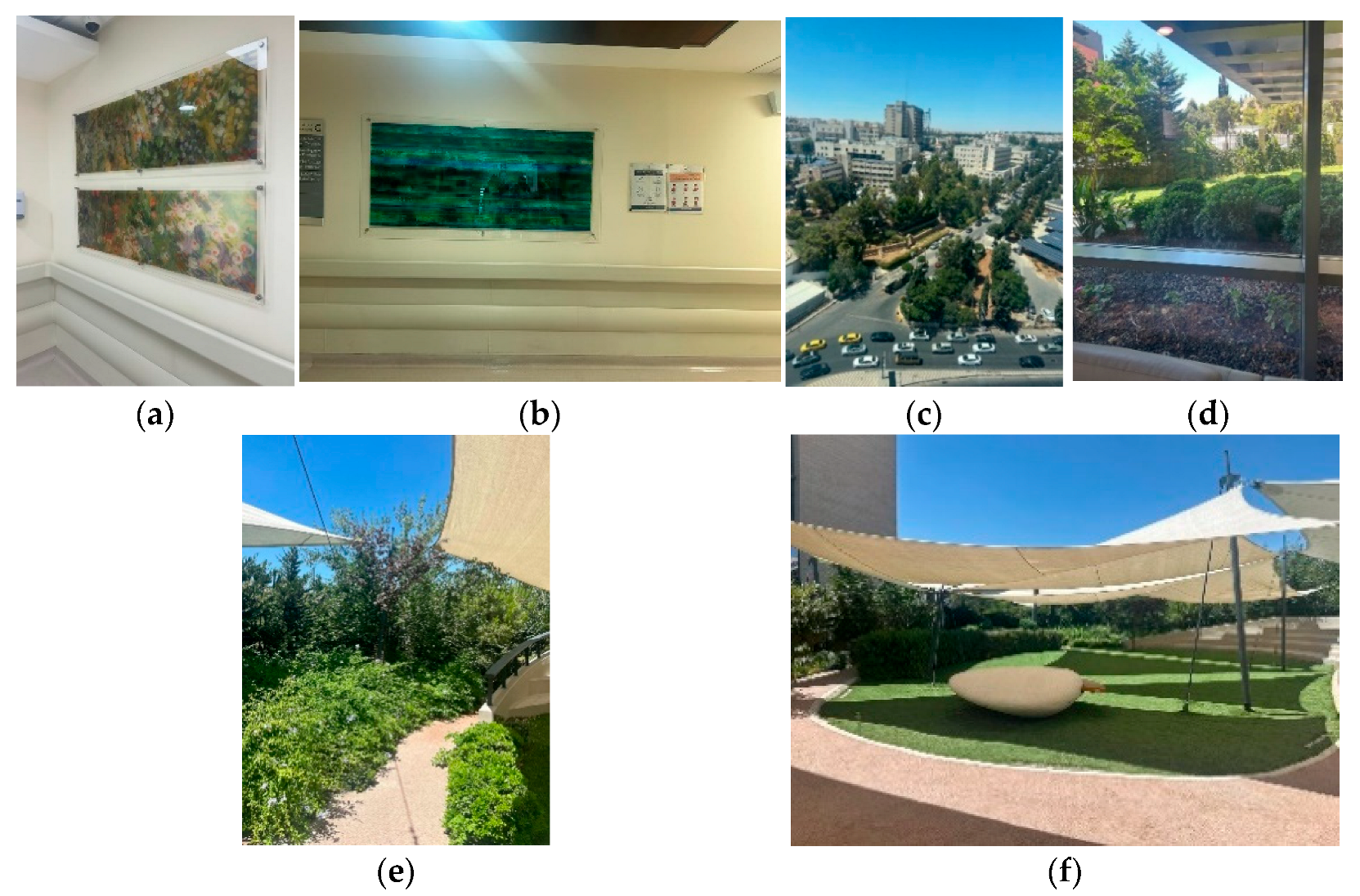

4.3.3. Greenery

4.3.4. Material Selection

4.4. Semi-Structured Interviews with Staff

- Air quality: Lung cancer patients are highly sensitive to the air quality; in their early stages they might not feel as acutely affected by air quality and may prefer fresh air via windows or any outdoor access. However, in the late stages, patients become more sensitive to poor air quality. As a result, filtered and purified air would be more critical for comfort in these stages. Leukemia and immune-sensitive patients have compromised immune systems due to their treatment, making them more vulnerable to infections. Environments with very strict air quality controls would be preferred in late stages. “Late-stage patients often ask for purified air or specific room types”, one oncologist noted.

- Daylight: Skin cancer patients need to avoid direct exposure to sunlight due to increased sensitivity to UV radiation. Furthermore, interviewees mentioned that daylight exposure on breast cancer patients is closely linked to improved mood and reduced depression and anxiety. Both types in early stages may still be active in spaces that are directly exposed to daylight. In late stages, patients might be confined to their rooms; as a result, large windows with controlled daylight options and views of nature can have a positive impact on their mood and mental well-being. “For skin cancer patients, we designed rooms facing north or shaded areas”, explained an architect who was interviewed.

- Greenery: Gastrointestinal cancer patients experience a lot of stress and discomfort because of their overall physical well-being. Such symptoms are noticed in hematological cancer patients who cannot spend time in large communal outdoor spaces but could still benefit from visual engagement with nature. In early stages, patients are still able to walk through green areas or even past green walls to feel the connection with nature. Nevertheless, in late stages, where patients are bedridden, green views from windows are required. Some procedure rooms and some inspection rooms have green views on the ceilings to provide a sense of peace and emotional relief.

- Material: Interviewees confirm that patients with sensory sensitivities, such as neurological cancer patients and the bone cancer patients, experience pain, making them more sensitive to hard surfaces or uncomfortable furniture textures, especially in their late stages when they spend extended periods in bed or seated. Materials that are antimicrobial, non-porous, and visually warm are essential for improving the air quality.

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the institution. |

References

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization; World Health Organization: New York, NY, USA, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Stichler, J.F. Creating healing environments in critical care units. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 2001, 24, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Biophilic theory and research for healthcare design. In Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, E.M. Healing Spaces: The Science of Place and Well-Being; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; Llinares, C.; Macagno, E. The cognitive-emotional design and study of architectural space: A scoping review of neuroarchitecture and its precursor approaches. Sensors 2021, 21, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R. Dimensions, elements, and attributes of biophilic design. In Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 2008, pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, T. (Ed.) Design for Health: Sustainable Approaches to Therapeutic Architecture; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Xu, T. Biophilic design as an important bridge for sustainable interaction between humans and the environment: Based on practice in Chinese healthcare space. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 8184534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, J.; Danielsen, A.; Rosenberg, J. Effects of environmental design on patient outcome: A systematic review. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2014, 7, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Joye, Y.; Dewitte, S. Nature’s broken path to restoration. A critical look at Attention Restoration Theory. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.H.; Kesten, J.M.; López-López, J.A.; Ijaz, S.; McAleenan, A.; Richards, A.; Gray, S.; Savović, J.; Audrey, S. The effects of changes to the built environment on the mental health and well-being of adults: Systematic review. Health Place 2018, 53, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, M.S.; Soebarto, V. Biophilia and Salutogenesis as restorative design approaches in healthcare architecture. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2019, 62, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Schröder, T.; Bekkering, J. Biophilic design in architecture and its contributions to health, well-being, and sustainability: A critical review. Front. Archit. Res. 2022, 11, 114–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marberry, S.O. Improving Healthcare with Better Building Design; Health Administration Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Malkin, J. A Visual Reference for Evidence-Based Design; Center for Health Design: Concord, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zimring, C.; Denham, M.E.; Jacob, J.T.; Cowan, D.Z.; Do, E.; Hall, K.; Kamerow, D.; Kasali, A.; Steinberg, J.P. Evidence-based design of healthcare facilities: Opportunities for research and practice in infection prevention. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawa, F.; Madathil, S.C.; Gittler, A.; Khasawneh, M.T. Advancing evidence-based healthcare facility design: A systematic literature review. Health Care Manag. Sci. 2020, 23, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, C.C.; Barnes, M. (Eds.) Healing Gardens: Therapeutic Benefits and Design Recommendations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gesler, W.M. Therapeutic landscapes: Theory and a case study of Epidauros, Greece. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1993, 11, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M.M.; Nordin, S.; Bernhardt, J.; Elf, M. Application of theory in studies of healthcare built environment research. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2020, 13, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaschke, S. The role of nature in cancer patients’ lives: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, S.; O’Callaghan, C.C.; Schofield, P. Cancer patients’ recommendations for nature-based design and engagement in oncology contexts: Qualitative research. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2018, 11, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, B.H.; Corcoran, R.; Gutiérrez, R.U. The impact of biophilic design in Maggie’s Centres: A meta-synthesis analysis. Front. Archit. Res. 2023, 12, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; World Bank Group. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Page, A.E.; Adler, N.E. (Eds.) Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Luker, K.; Campbell, M.; Amir, Z.; Davies, L. A UK survey of the impact of cancer on employment. Occup. Med. 2013, 63, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S. Psychosocial impact of cancer. In Psycho-Oncology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.; Kelly, B. Emotional dimensions of chronic disease. West. J. Med. 2000, 172, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kudesia, P.; Shi, Q.; Gandhi, R. Anxiety and depression in patients with osteoarthritis: Impact and management challenges. Open Access Rheumatol. Res. Rev. 2016, 8, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, M.H.; Moreno, P.I.; Penedo, F.J. Stress management interventions to facilitate psychological and physiological adaptation and optimal health outcomes in cancer patients and survivors. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 423–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Mattson, R.H. Ornamental indoor plants in hospital rooms enhanced health outcomes of patients recovering from surgery. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJean, D.; Giacomini, M.; Vanstone, M.; Brundisini, F. Patient experiences of depression and anxiety with chronic disease: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont. Health Technol. Assess. Ser. 2013, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weschler, C.J.; Carslaw, N. Indoor chemistry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2419–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotradyova, V.; Vavrinsky, E.; Kalinakova, B.; Petro, D.; Jansakova, K.; Boles, M.; Svobodova, H. Wood and its impact on humans and environment quality in health care facilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyendo, T.O.; Uwajeh, P.C.; Ikenna, E.S. The therapeutic impacts of environmental design interventions on wellness in clinical settings: A narrative review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2016, 24, 174–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S.; Gesler, W.; Fabian, K.; Francis, S.; Priebe, S. Therapeutic landscapes in hospital design: A qualitative assessment by staff and service users of the design of a new mental health inpatient unit. Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2007, 25, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenks, C.; Heathcote, E. The Architecture of Hope; Frances Lincoln: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A. (Ed.) Therapeutic Landscapes; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, L.; Corazon, S.S.; Stigsdotter, U.K. Nature exposure and its effects on immune system functioning: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebaid, M.A. A framework for implementing biophilic design in cancer healthcare spaces to enhance patients’ experience. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2023, 14, 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Browning, W.D.; Ryan, C.O. 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health and Well-Being in the Built Environment; Terrapin Bright Green: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.; Calabrese, E. The Practice of Biophilic Design; Terrapin Bright LLC.: London, UK, 2015; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, C.C.; Sachs, N.A. Therapeutic Landscapes: An Evidence-Based Approach to Designing Healing Gardens and Restorative Outdoor Spaces; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin, B.H.; Izmir Tunahan, G.; Disci, Z.N.; Ozer, H.S. Biophilic design in the built environment: Trends, gaps and future directions. Buildings 2025, 15, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, S.H.; Chang, C.Y. Health benefits of evidence-based biophilic-designed environments: A review. J. People Plants Environ. 2021, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1); United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Parsia, Y.; Tamyez, P.F. Role of healthcare-facilities layout design, healing architecture, on quality of services. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 598–601. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, A.; Rashid, M. The architecture of safety: Hospital design. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2007, 13, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddicoat, S.; Badcock, P.; Killackey, E. Principles for designing the built environment of mental health services. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. Effects of healthcare environmental design on medical outcomes. In Design and Health: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Health and Design; Svensk Byggtjanst: Stockholm, Sweden, 2001; Volume 49, p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Kokulu, N.; Ozgunler, S.A. Evaluation of the effects of building materials on human health and healthy material selection. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2019, 32, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, T.; Sturge, J.; Duff, C. Healing architecture in healthcare: A scoping review. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2022, 15, 315–328. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, T.P. The Spatial Organization of Psychiatric Practice: A Situated Inquiry into ‘Healing Architecture’. Ph.D. Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abulawi, R.; Walker, S.; Boyko, C. Healing by design: Design of public spaces for children’s hospitals. In Research into Design for a Connected World: Proceedings of ICoRD 2019 Volume 2; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 427–438. [Google Scholar]

- Pradinuk, R. Incentivizing the daylit hospital: The green guide for health care approach. Health Environ. Res. Des. J. 2009, 2, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeil, E.M.; Sobaih, A.E.E. Enhancing healing environment and sustainable finishing materials in healthcare buildings. Buildings 2022, 12, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaras, G. A State-of-the-Art Review of Healthcare Acoustics. Sound Vib. 2014, 48, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson, Å.; Tillman, A.M.; Svensson, T. Life cycle assessment of flooring materials: Case study. Build. Environ. 1997, 32, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minne, E.; Crittenden, J.C. Impact of maintenance on life cycle impact and cost assessment for residential flooring options. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanska, A. Construction and material issues and usage prospects of antique wooden beam floors. In Performance and Maintenance of Bio-Based Building Materials Influencing the Life Cycle and LCA; University of Ljubljana Biotechnical Faculty and University of Primorska: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2014; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Patkó, C.; Adamik, P.; Pásztory, Z. The Effect of Wooden Building Materials on the Indoor Air Quality of Houses. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: London, UK, 2024; Volume 514, p. 04003. [Google Scholar]

- Elfakhri, S.O. Antibacterial Activity of Novel Self-Disinfecting Surface Coatings; University of Salford: Salford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luk, S.; Chow, V.C.Y.; Yu, K.C.H.; Hsu, E.K.; Tsang, N.C.; Chuang, V.W.M.; Lai, C.K.C.; Hui, M.; Lee, R.A.; Lai, W.M.; et al. Effectiveness of antimicrobial hospital curtains on reducing bacterial contamination—A multicenter study. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, S.M. The impact of the ideology of advanced technologies in design and technology on Corian as one of the smart materials and its applications to the interior design of residential building. J. Des. Sci. Appl. Arts 2020, 1, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagioli, V.; Piredda, M.; Annibali, O.; Tirindelli, M.C.; Pignatelli, A.; Marchesi, F.; Mauroni, M.R.; Soave, S.; Del Giudice, E.; Ponticelli, E.; et al. Factors influencing the perception of protective isolation in patients undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A multicentre prospective study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, A.; D’Alessandro, D. Air bio-contamination control in hospital environment by UV-C rays and HEPA filters in HVAC systems. Ann. Di Ig. Med. Prev. E Di Comunita 2020, 32, 449–461. [Google Scholar]

- Morganroth, P.A.; Lim, H.W.; Burnett, C.T. Ultraviolet radiation and the skin: An in-depth review. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2013, 7, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Begum, R.; Maqbool, M. Ultraviolet Radiation: Benefits, Harms, Protection. Introd. Non-Ioniz. Radiat. 2023, 2, 62. [Google Scholar]

| BD Elements | SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being | SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | SDG 13: Climate Action | SDG 15: Life on Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh Air | Improves respiratory health, contributing to overall well-being. | Promotes healthier environments through improved air quality in cities. | Improves air quality and reduces need for energy-intensive air-conditioning. | Promotes sustainable urban environments through green infrastructure. |

| Light-Sunlight | Regulates circadian rhythms, improves mood, and supports faster recovery. | Natural lighting reduces energy use and supports sustainable building design. | Lowers carbon footprint by minimizing the need for artificial lighting. | Reduces environmental impact through energy savings. |

| Greenery | Reduces stress and enhances mental well-being, speeding up recovery. | Green spaces improve urban biodiversity and provide restorative environments. | Green infrastructure contributes to climate resilience. | Supports biodiversity and ecosystem health within and around healthcare environments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Dmour, Y. Optimizing Cancer Care Environments: Integrating Indoor Air Quality, Daylight, Greenery, and Materials Through Biophilic and Evidence-Based Design. Architecture 2025, 5, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040122

Al-Dmour Y. Optimizing Cancer Care Environments: Integrating Indoor Air Quality, Daylight, Greenery, and Materials Through Biophilic and Evidence-Based Design. Architecture. 2025; 5(4):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040122

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Dmour, Youmna. 2025. "Optimizing Cancer Care Environments: Integrating Indoor Air Quality, Daylight, Greenery, and Materials Through Biophilic and Evidence-Based Design" Architecture 5, no. 4: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040122

APA StyleAl-Dmour, Y. (2025). Optimizing Cancer Care Environments: Integrating Indoor Air Quality, Daylight, Greenery, and Materials Through Biophilic and Evidence-Based Design. Architecture, 5(4), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040122