Agency, Resilience and ‘Surviving Well’ in Dutch Neighborhood Living Rooms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Community Resilience

2.2. Social Infrastructure

3. Methodology

3.1. Background

3.2. Ethnographic Study

4. Buurthuiskamers in The Netherlands

4.1. The Evolution of the Buurthuiskamer

4.2. The Contemporary Buurthuiskamer

5. Practices of Resilience and Agency

5.1. Surviving

5.2. Thriving

[Initiator] thanked [younger participant] for raising these issues and said how positive he finds it that she feels safe and able to do so; for him it is valuable that the tensions and conflicts under the surface are brought up and used productively. However, he did not engage further with the substance of what she had said. It was suggested that a smaller working group take this further (…) [younger participant] clearly wanted to continue discussing the issue, but at this point [paid coordinator] interrupted to ask for our attention for the newspaper launch……Later, [younger participant] would tell me that these conflict moments often ended on ‘a sort of unspoken “agree to disagree”’ in the interest of time.

5.3. Transforming

‘it’s kind of a chaotic space, but precisely that gives it the power, from out of chaos, to make things happen, things that couldn’t happen anywhere else. There’s a sort of feeling of freedom, that everyone who comes here, I think, is looking for…the feeling that you are welcomed, and you have the space—spiritually but also the physical space—to do the things you’d really like to do.’

6. Discussion

6.1. The Precarity of Resilience

6.2. A Neutral Infrastructure or a Home in the City?

6.3. Mediating Between State and Community

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walker, J.; Cooper, M. Genealogies of Resilience: From Systems Ecology to the Political Economy of Crisis Adaptation. Secur. Dialogue 2011, 42, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monstadt, J.; Schmidt, M. Urban resilience in the making? The governance of critical infrastructures in German cities. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2353–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, E.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Howes, M. A framework for using the concept of urban resilience in responding to climate-related disasters. Urban Res. Pract. 2021, 15, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L.J. The politics of resilient cities: Whose resilience and whose city? Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geogr. 2016, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, M. Resilience and Responsibility: Governing Uncertainty in a Complex World. Geogr. J. 2014, 180, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebrowski, C. Postneoliberal Resilience: Interrogating the Value of the Resilience Multiple in the Post-COVID-19 Conjunctural Crisis. Geoforum 2025, 158, 104162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretney, R.; Bond, S. ‘Bouncing Back’ to Capitalism? Grass-Roots Autonomous Activism in Shaping Discourses of Resilience and Transformation Following Disaster. Resilience 2014, 2, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaika, M. ‘Don’t Call Me Resilient Again!’: The New Urban Agenda as Immunology … or … What Happens When Communities Refuse to Be Vaccinated with ‘Smart Cities’ and Indicators. Environ. Urban. 2017, 29, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, C. Resilience Praxis as a Function of Coloniality: Rethinking Modernity, Resistance, and Participation in Adaptation Governance. Antipode 2025, 57, 1792–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P. Resilience, Ecology and Adaptation in the Experimental City. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 36, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S. Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End? Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretney, R. Resilience for Whom? Emerging critical geographies of socio-ecological resilience. Geogr. Compass 2014, 8/9, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S. Just Resilience. City Community 2018, 17, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVerteuil, G.; Golubchikov, O. Can Resilience Be Redeemed?: Resilience as a Metaphor for Change, Not against Change. City 2016, 20, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcou, C.; Petrescu, D. R-URBAN or How to Co-Produce a Resilient City. Ephemer. Theory Politics Organ. 2015, 15, 249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Graham, J.K.; Cameron, J.; Healy, S. Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A.P. Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilin, R.; Wilkinson, C. Introduction: Governing for Urban Resilience. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Kelly, P.M.; Winkels, A.; Huy, L.Q.; Locke, C. Migration, Remittances, Livelihood Trajectories, and Social Resilience. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2022, 31, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.; Derickson, K.D. From Resilience to Resourcefulness: A Critique of Resilience Policy and Activism. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2012, 37, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J.; Tickell, A. Neoliberalizing Space. Antipode 2002, 34, 380–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S.; Lewis, T. Making Resilience: Everyday Affect and Global Affiliation in Australian Slow Cities. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 21, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carli, B. Micro-resilience and justice in Sao Paulo. In Architecture and Resilience: Interdisciplinary Dialogues; Trogal, K., Bauman, I., Lawrence, R., Petrescu, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K. Global Environmental Change I: A Social Turn for Resilience? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larner, W.; Moreton, S. Creating Resilient Subjects: The Coexist Project. In Governing Practices: Neoliberalism, Governmentality, and the Ethnographic Imaginary; Brady, M., Lippert, R.K., Eds.; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, Canada, 2016; pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- O’Grady, N. On the Possibility of ‘Just Resilience’: A Pragmatist Approach to Justice-Based Climate Change Governance. Geoforum 2025, 159, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, J. Performances and Performativities of Resilience. In Evolutionary Governance Theory; Beunen, R., Van Assche, K., Duineveld, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 167–183. ISBN 978-3-319-12273-1. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D.D.; Kulig, J.C. The Concept of Resiliency: Theoretical Lessons from Community Research. Health Can. Soc. 1997, 4, 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.; Westaway, E. Agency, Capacity, and Resilience to Environmental Change: Lessons from Human Development, Well-Being, and Disasters. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2011, 36, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots Innovations for Sustainable Development: Towards a New Research and Policy Agenda. Environ. Politics 2007, 16, 584–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, M.E.; Silva, P.; Barr, C.; Golshani, Z.; Lee, E.; Ligas, R.; Mosher, E.; Reynosa, A. Civic Ecology Practices: Insights from Practice Theory. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingerland, G.; Edua-Mensah, E.; van Gils, M.; Kleinhans, R.; Brazier, F. We’re in This Together: Capacities and Relationships to Enable Community Resilience. Urban Res. Pract. 2023, 16, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Marlowe & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A. Lively Infrastructure. Theory Cult. Soc. 2014, 31, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinenberg, E. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life; Penguin Random House: New York, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, A.; Layton, J. Social Infrastructure and the Public Life of Cities: Studying Urban Sociality and Public Spaces. Geogr. Compass 2019, 13, e12444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, A.; Layton, J. Social Infrastructure: Why It Matters and How Urban Geographers Might Study It. Urban Geogr. 2022, 43, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enneking, G.; Custers, G.; Engbersen, G. The rapid rise of social infrastructure: Mapping the concept through a systematic scoping review. Cities 2025, 158, 105608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, A. Ritornello: “People as Infrastructure”. Urban Geogr. 2012, 42, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, R.; Canarte, D.; Vitale, T. Beyond ethnic solidarity: The diversity and specialisation ofsocial ties in a stigmatised migrant minority. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022, 48, 3113–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, C.; Fisher, C.; Howat, P.; Wood, L. The essence of being connected: The lived experience of mothers with young children in newer residential areas. Community Work Fam. 2014, 17, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, A.; Sheringham, O. Home-city geographies: Urban dwelling and mobility. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2018, 43, 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierup, C.; Alund, A.; Kellecioglu, I. Reinventing the People’s House: Time, Space and Activism in Multiethnic Stockholm. Crit. Sociol. 2020, 47, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONECT. Dynamic Archive of Collective Practices of Everyday Community Resilience. Available online: https://jpiconect.gogocarto.fr/map (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Haraway, D. Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem. Stud. 1988, 14, 575–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, S. Situating Everyday Life: Practices and Places; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nijenhuis, H. Werk in de Schaduw: Club-en Buurthuizen in Nederland, 1892–1970; Stichting Beheer IISG: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lijphart, A. The Politics of Accommodation: Pluralism and Democracy in the Netherlands; University of California Press: Oakland CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- van Dam, P. Constructing a Modern Society Through “Depillarization”. Understanding Post-War History as Gradual Change. J. Hist. Sociol. 2015, 28, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spierts, M.J.S. Stille Krachten van de Verzorgingsstaat: De Precaire Professionalisering van de Sociaal-Culturele Beroepen. PhD Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- van Gerven, M. The Dutch Participatory State. In Routledge Handbook of European Welfare Systems, 2nd ed.; Blum, S., Kuhlmann, J., Schubert, K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 387–403. ISBN 978-0-429-29051-0. [Google Scholar]

- Aalbers, M.B.; van Loon, J.; Fernandez, R. The Financialization of a Social Housing Provider. Int. J. Urban Res. 2017, 41, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delsen, L. The Realisation of the Participation Society. Welfare State Reform in the Netherlands: 2010–2015; Working Paper; Radboud University Institute for Management Research: Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wilde, M. Home is Where the Habit of the Heart is: Governing a gendered sphere of belonging. Home Cult. 2016, 13, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peperkamp, E.; Haumahu, D.E.G.T. The community ‘living room’–social interactions and social capital in a community activity in the Netherlands. Leis. Stud. 2022, 43, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlleCijfers. Statistieken Buurt Drents Dorp. Available online: https://allecijfers.nl/buurt/drents-dorp-eindhoven/ (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- AlleCijfers. Statistieken Buurt Het Ven. Available online: https://allecijfers.nl/buurt/het-ven-eindhoven/ (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- AlleCijfers. Statistieken Buurt Tussendijken. Available online: https://allecijfers.nl/buurt/tussendijken-rotterdam/ (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- AlleCijfers. Statistieken Buurt Bospolder. Available online: https://allecijfers.nl/buurt/bospolder-rotterdam/ (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Gemeente Rotterdam. Veerkrachtig BoTu 2028: In Tien Jaar Naar Het Stedelijk Sociaal Gemiddelde (Programma); Gemeente Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2019.

- De Gasperi, F.; Walliser Martinez, A. Shaping caring cities: A study of community-based mutual support networks in post-pandemic Madrid. J. Urban Aff. 2024, 47, 2756–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosol, M. Community volunteering as neoliberal strategy? Green space production in Berlin. Antipode 2012, 44, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veron, O. ‘We’re just an ambulance at the bottom of the cliff’: Strategies and (a)politics of change in Berlin’s community food spaces. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2023, 55, 1670–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. Playing with the rules of the game: Social innovation for urban transformation. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2019, 43, 1168–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Galès, P.; Vitale, T. Governing the Large Metropolis. A Research Agenda; Working Paper; Sciences Po: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| De Nieuwe Maan | Buurthuis ‘t Struikske | Huis van de Toekomst | Het Bollenpandje | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inception | 2022 | 2023 | 2019 | 2020 |

| Initiator(s) | Local welfare organization | Residents’ association | Artist researchers | Active residents |

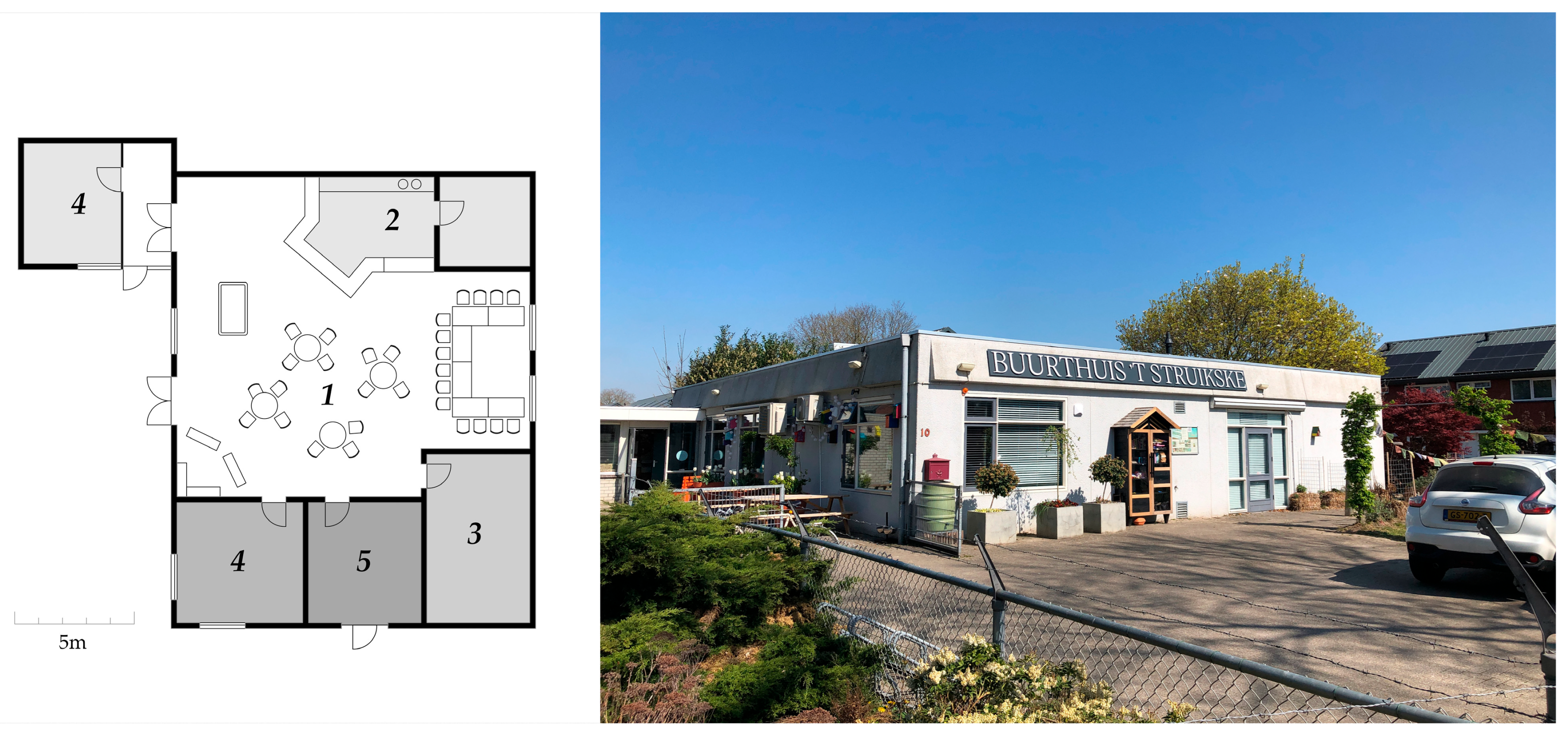

| Space | Former commercial space in ground-floor corner of a terraced housing block | Pavilion building formerly used as special needs youth center | Vacant former commercial space in ground-floor corner of social housing apartment block | Vacant former commercial space in ground-floor corner of a terraced housing block |

| Size (approx.) | 110 m2 | 300 m2 | 70 m2 | 85 m2 |

| Tenure | Rent-free access from housing association | Building: purchased for nominal sum from previous owners Land: ten-year leasehold granted by municipality | Rented from housing association through temporary vacancy management business | Rented from housing association with municipal subsidy |

| Typical schedule | Weekdays 10–17 h Occasional evenings | Weekdays, 2–4 h depending on activity | Variable, 1–3 days per week depending on programming and availability | Weekdays, usually 10–15 h but varies greatly |

| Funding | Municipal subsidy, welfare organizations (labor) and housing association (space) | Municipal subsidies; income from space rental; municipal leasehold | Artistic institution (initial); philanthropic organizations (ongoing); coalition of municipality, housing association and energy company (2023–2024) | Municipal subsidy through ‘Resilient BoTu 2028′ program; philanthropic organizations; project-based funding for artistic and social interventions |

| Governance | Welfare organization, in collaboration with local residents’ association | Residents’ association and dedicated board | Steering group of initiators and key actors; oversight by association board since end 2024 | Initiators and long-term participants; administrative oversight by formal association |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Botha, L.; Druta, O.; van Wesemael, P. Agency, Resilience and ‘Surviving Well’ in Dutch Neighborhood Living Rooms. Architecture 2025, 5, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040101

Botha L, Druta O, van Wesemael P. Agency, Resilience and ‘Surviving Well’ in Dutch Neighborhood Living Rooms. Architecture. 2025; 5(4):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040101

Chicago/Turabian StyleBotha, Louwrens, Oana Druta, and Pieter van Wesemael. 2025. "Agency, Resilience and ‘Surviving Well’ in Dutch Neighborhood Living Rooms" Architecture 5, no. 4: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040101

APA StyleBotha, L., Druta, O., & van Wesemael, P. (2025). Agency, Resilience and ‘Surviving Well’ in Dutch Neighborhood Living Rooms. Architecture, 5(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/architecture5040101