Abstract

Despite a global trend toward socially engaged higher education, architectural pedagogy continues to grapple for a coherent approach that systematically and genuinely integrates socio-cultural dimensions into design studio teaching practices. Defined as the interwoven social, cultural, and political factors that shape the built environment, the socius is treated peripherally within architectural pedagogy, limiting students’ capacity to develop civic agency, spatial justice awareness, and critical reflexivity in navigating complex societal conditions. This article argues for a socius-centric reorientation of architectural pedagogy, postulating that socially engaged studio models, which include Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project, must be conceptually integrated to fully harness their pedagogical merits. The article adopts two lines of inquiry: first, mapping the theoretical underpinnings of the socius across award-winning pedagogical innovations and Google Scholar citation patterns; and second, defining the core attributes of socially engaged pedagogical models through a bibliometric analysis of 87 seminal publications. Synthesising the outcomes of these inquiries, the study offers an advanced articulation of studio learning as a process of social construction, where architectural knowledge is co-produced through role exchange, iterative feedback, interdisciplinary dialogue, and emergent agency. Conclusions are drawn to offer pragmatic and theoretically grounded pathways to reshape studio learning as a site of civic transformation.

1. Introduction

Socially engaged pedagogical approaches are gaining momentum across diverse disciplines within higher education worldwide. Yet, architectural pedagogy continues to lack a coherent approach for meaningfully incorporating socio-cultural dimensions into design studio teaching. The socius, defined operationally as the symbiotic web of social, cultural, and political dynamics that shape the built environment, is often treated tangentially in design studio teaching practices. As a result, students are insufficiently prepared to develop the civic agency, spatial justice awareness, and critical reflexivity required to engage with complex societal challenges. This article confronts the persistent gap between architectural pedagogy and the social contexts it unsurprisingly impacts, by introducing three interchangeable pedagogical models, namely Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project.

The thrust of the article stems from a critique of the canonical pedagogical tradition, which continues to dominate architectural education globally. This canonical tradition has its roots in state-sponsored institutions and influential craft movements, most notably the École des Beaux-Arts in France, the Bauhaus in Germany, and Vkhutemas in Russia. These institutions laid the groundwork for design education: the École des Beaux-Arts, founded in the seventeenth century, focused on classical principles, drawing, and composition, while the Bauhaus and Vkhutemas redefined the role of the architect by merging architecture with art, design, craft, and industrial production under the influence of the Modernist and Constructivist movements [1,2]. These models powerfully shaped architectural curricula worldwide and institutionalised a design ethos that gave primacy to formal aesthetics and artistic mastery. Today, the growing complexities of social, cultural, and political forces that shape, and are shaped by, the built environment warrant positioning the socius as an organising principle in architectural pedagogy. In this respect, the socius is envisaged to reorient how architectural knowledge is produced, transmitted, and embedded in society.

1.1. Aim and Objectives

The study responds to the lack of engaging social dynamics in studio teaching practices by proposing a socius-centric pedagogy, which is rooted in learning models that recognise architecture both as a design discipline and as a field of relational, situated, and negotiated knowledge. Such a pedagogy accentuates that the processes through which design knowledge is co-constructed among multiple actors should include students, communities, practitioners, and institutions. It operates across physical, digital, and conceptual boundaries. It emphasises learning as a participatory act embedded within real-world constraints and possibilities. Central to this reorientation is the redefinition of studio culture. Rather than functioning exclusively as a space of expert-driven problem solving, the design studio is conceived as a forum for critical inquiry and a platform for contested meaning-making, collaborative authorship, and iterative feedback. Within this space, architectural learning is not only about producing compelling proposals or elegant forms, but about understanding how those proposals emerge from, and feed back into, social structures and lived experiences.

To address the disconnection between architectural pedagogy and the social contexts future architects seek to serve, the article situates three pedagogical models: Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project within their broader social, cultural, and political contexts, elucidating how they can be integrated to foster transformative, civically resilient pedagogy. Specifically, the objectives of the study are the following:

- Examine the theoretical tenets, instructional strategies, and documented social impacts of the Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project pedagogical models.

- Identify and articulate the defining attributes that shape engagement with the socius in each of the three models.

- Explore how selected studio exemplars demonstrate the potential of these pedagogies to meaningfully embed the socius within design studio teaching practices.

Reframing architectural education as an act of social construction where spatial knowledge is continuously shaped by, and shaping, broader systems of meaning, the article aims to provide a more integrated, theoretically grounded, and methodologically coherent synthesis for socially engaged studio teaching. In performing this way, it contributes to an evolving discourse that seeks to train future professionals and to cultivate reflective, responsive, and resilient citizens.

1.2. Responsive Investigation and Operational Outlook

The conceptual repositioning of the socius in architectural pedagogy is supported by two intersecting lines of inquiry. The first line of inquiry involves a theoretical and empirical mapping of how key theoretical tenets have been historically raised within the literature of Community Design, Design-Build, and Live Project pedagogy. A citation-based analysis of key theoretical pairings reveals how specific concepts are disproportionately concentrated in certain studio types and how others remain underutilised, suggesting opportunities for more deliberate cross-pollination of ideas. The analysis of award-winning international studios further illustrates how diverse institutions have operationalised these models in projects that give primacy to participatory design and spatial equity.

The second line of inquiry builds upon a targeted review of 87 seminal peer-reviewed publications drawn from a corpus of over 200 academic sources. This review identifies and synthesises shared pedagogical attributes across the three models, such as stakeholder negotiation, iterative prototyping, and ethical co-design. It additionally maps the intellectual genealogies and thematic clusters that underpin each model, serving to clarify the principles and patterns that constitute a coherent approach to socially engaged studio teaching.

From this foundation, the study advances synthesised thinking for architectural pedagogy, which is predicated on four interwoven processes that characterise a robust engagement with the socius. Firstly, it involves a transformation of traditional roles and hierarchies within the design studio where the learning environment encourages students and community partners alike to exchange roles, reflect on positionalities, and engage in mutual critique. The second incorporates learning methods rooted in action, where studio work is no longer structured around a linear sequence of research, concept, design, and presentation. Instead, it adopts a cyclical and recursive process where inquiry, analysis, design, and reflection unfold in parallel. The third treats the studio as a site of collective sense-making where learning is framed as a co-produced understanding constructed through dialogue, negotiation, and shared experimentation. The fourth supports the emergence of ownership, both in the sense of project authorship and in the deeper sense of civic agency.

The study contends that when these pedagogical processes are integrated across and within Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project pedagogical models, a transformative pedagogy becomes possible. Each model contributes unique strengths, including the political grounding and stakeholder sensitivity of Community Design; the material, procedural, and evaluative rigour of Design–Build; and the institutional negotiation and ethical nuance of Live Project work. However, it is only through the synthesis of their qualities that their full potential to integrate the socius is realised.

2. Building the Case for the Socius in Architectural Pedagogy

Over the past several decades, the canonical tradition of architectural pedagogy has come under critical scrutiny [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Scholars and educators have raised fundamental concerns about its content and pedagogical processes. The primary critique was centred on the assertion that the canonical model inadequately prepares students for the complex realities of architectural practice [3,4,5]. Graduates often lack engagement with economic, social, and ethical considerations, and are insufficiently equipped to respond to client needs, regulatory frameworks, or broader societal dynamics [6,7,8,9]. Such curricula and studios tend to marginalise political and socio-cultural imperatives, reinforcing a disconnection between design education and the contexts it intends to serve.

Critics have also interrogated the pedagogical style itself [1,9,10,11,12,13,14]. The master–apprentice dynamic, central to the canonical tradition, has been criticised for favouring hierarchical authority and stylistic mimicry over student agency and collaborative inquiry. Practices such as the desk critique, where an educator often overwrites student work without dialogue, exemplify a broader culture that discourages critical engagement and sustains power imbalances [15,16,17]. Donald Schön’s seminal critique labelled this approach the “mastery-mystery” model, where knowledge is transmitted through opaque demonstration rather than mutual reflection. This results in restricting opportunities for dialogue, social engagement, and collective authorship, despite the inherently collaborative nature of architectural practice [18,19,20].

The emergence of alternative pedagogical models over the past decades coincides with increasingly significant social and political transformations. The rise in social housing agendas, urban renewal efforts, and the reclamation of historic environments, all evolving in parallel to rapid urbanisation and population growth, continue to expose the limitations of the canonical tradition. These challenges continue to inspire a reorientation of architectural education, prompting the establishment of community-focused initiatives and pedagogical experiments that prioritise user engagement, cultural diversity, and interdisciplinary inquiry.

One of the most enduring outcomes of this reorientation was the establishment of Community Design Centres (CDCs) [21]. These centres mobilised students and tutors to address the needs of under-resourced communities through real-world design engagement. The CDC model evolved into community engagement workshops and focused groups discussions, practice-based environments often embedded within architecture schools, providing hands-on learning through partnerships with clients, local practitioners, and civic organisations. These initiatives offered an alternative to abstract or hypothetical studio briefs by immersing students in socio-political realities, expanding their understanding of the public role of architecture, predicated on service, responsibility, and impact. Despite initial resistance from the architectural establishment, these pedagogical experiments catalysed widespread curricular shifts from the late 1980s to the present. Now, many schools integrate studio models that respond to pressing urban, social, and environmental challenges. This includes interdisciplinary specialisations and the expansion of practice-oriented, community-based learning that continues to inform contemporary design pedagogy.

By and large, the critique of the canonical tradition elucidates its deficiencies in both content and method. In response, architectural pedagogy has increasingly embraced models that reposition the architect not as an isolated visionary conceptual designer, but as a socially embedded, critically reflective agent. Coupled with the calls for critical and transformative pedagogies, these shifts reflect a broader transformation in how architecture is taught and practised, toward a more equitable, inclusive, and engaged discipline.

On the one hand, critical pedagogy aims at reconfiguring the traditional student/teacher relationship, where the teacher is the active agent and the knowledge provider, and the students are the passive recipients of the teacher’s knowledge. Grounded on the experiences of both students and teachers, new knowledge is produced through the dialogical process of learning. In essence, critical pedagogy is viewed as an approach to teaching which attempts to help students question and challenge domination and the beliefs and practices that dominate [17,22].

On the other hand, transformative pedagogy, a term that refers to interactional processes and dialogues between educators and students that invigorate the collaborative creation and distribution of power in learning settings. As a concept, it is based on the fact that the interaction between educators and students reflects and fosters broader societal patterns. While transformative pedagogy is not confined to a static definition, it builds on the perspectives of critical pedagogy and its underlying hidden curriculum concept, which refers to those unstated values that stem tacitly from the social relation of the learning setting [22].

While the proliferation of socially engaged studio models, particularly Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project, has seen a welcome turn toward civic relevance, the field still suffers from a lack of conceptual integration and methodological cohesion. These models tend to operate as discrete pedagogical strands, each with its own set of values, tools, and modes of engagement, but are rarely grounded in a shared theoretical language. Consequently, their potential is often constrained by fragmented practices and limited evaluative frameworks. The absence of an integrated paradigm for understanding how social dynamics are enacted within studio contexts results in an under-exploitation of the capacity of architectural pedagogy to cultivate civic agency, spatial justice, and long-term social resilience.

3. A Multilayered Approach to Inquiry

The investigation proceeds along two complementary lines of inquiry. Each of which is designed to map, characterise, and operationalise the socius in architectural pedagogy.

3.1. Framing the Socius Through Theories and Award-Winning Pedagogical Innovations

This first line of inquiry establishes the experiential foundation of the study. The inquiry began by constructing a robust theoretical structure that draws on relational ontology, critical constructivism, experiential learning, dialogic pedagogy, reflective practice, and decolonial thought. The purpose of this initial step was to utilise the socius as an organising conceptual lens. This was followed by identifying thirteen key theoretical perspectives, where each was paired with the terms “Community Design,” “Design-Build,” and “Live Project” alongside “architecture education” in Google Scholar searches.

The total number of hits for each pairing was noted and rounded to the nearest hundred to smooth minor daily fluctuations in search results and to emphasise their role as approximate indicators of scholarly prominence rather than precise metrics. These counts were then visualised in a grouped bar chart to demonstrate which theoretical perspectives are most often invoked in, or associated with, each studio model.

To quantify the prominence and historical emergence of each pedagogical and theoretical keyword, the study employed systematic Google Scholar searches using the exact string “keyword” AND “architecture education” (for example, “participatory mapping” AND “architecture education” AND “dialogic pedagogy”). For each term, the total number of results displayed at the top of the search page was recorded and rounded to the nearest hundred as a proxy for its overall presence in the discourse. To approximate each keyword’s initial appearance, the “Tools” menu’s custom date-range feature was applied to successive intervals (for example, 1968–1970), noting whether any results were returned within those bounds. This process was repeated for every pedagogical and theoretical term to produce a fully reproducible dataset of relative frequency and temporal origin across the architectural education literature.

Quantifying how often each key theory appears in conjunction with the three models in the existing body of knowledge in architectural education, the study moves beyond anecdote and opinion. The resulting citation counts revealed which theoretical lenses are most deeply embedded in each pedagogical model. This empirical approach was necessary to ensure that subsequent characterisation and theoretical underpinnings of each model reflect the actual scholarly discourse.

Moreover, since the core of the study is to identify how each studio teaching model integrates the socius, mapping these theory-to-pedagogy alignments offers a data-driven basis for identifying which conceptual frameworks truly drive social, cultural, and political engagement in each approach.

Demonstrating world-wide efforts, the framing includes analysis of seven relevant award-winning studio outcomes identified from the Union Internationale des Architectes (UIA) Award for Innovation in Architectural Education from 2019 and 2023 award cycles. This was conducted by utilising structured coding of participatory workflows, interdisciplinary alliances, and analogue/digital methods to distil exemplary mechanisms for embedding the dynamics of the socius into studio teaching practices.

3.2. Defining Attributes of Socially Engaged Studio Teaching Models

Building on insights from the analysis of awarded studio outcomes, this second line of inquiry combines bibliometric mapping with conceptual synthesis to delineate the core attributes of each pedagogical model. A targeted corpus of over 200 peer-reviewed articles, sourced from Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar, identified through keyword search, was screened to yield 87 seminal publications (30 for Community Design, 29 for Design–Build, and 28 for Live Project pedagogy). The selection process followed four criteria: (a) ‘focus relevance’ required that each source explicitly address one of the three studio models; (b) ‘citation impact’ prioritised works in the top 10% of citations within that subfield; (c) ‘temporal balance’ ensured representation across the full pedagogical timeline; and (d) ‘methodological rigour’ mandated clear empirical or theoretical grounding.

Co-citation network analysis and keyword co-occurrence (via Google Scholar hits) were conducted to trace each model’s intellectual genealogy and thematic clusters. All searches were conducted without date limits, and the total number of results returned was rounded to the nearest hundred. To establish when each concept first appeared in the discourse, Google Scholar’s year-range filter was used to locate the earliest substantial clusters of results. While these hit counts serve only as a rough indicator of a theme’s scholarly visibility, they offer a consistent, comparative measure of how frequently key pedagogical concepts have been discussed in the discourse on architectural education. A final comparative visualisation plotted each keyword’s normalised hit count across the three models to reveal which concepts are most strongly associated with each pedagogy and where overlaps occur. This highlights both model-specific emphases and cross-cutting themes. The procedure for keyword search included the following:

- Community Design collection prioritised scholarship on “community participation,” “participatory design,” and “service-learning,” with particular attention to methodological tools such as “charrettes,” “pattern language,” and “stakeholder negotiation.” Works addressing “social responsibility” and “equity in design” ensured that the corpus reflected justice-oriented, collaborative praxis.

- Design–Build collection emphasised end-to-end studio engagement spanning conceptualisation, fabrication, and evaluation, and, therefore, incorporated terms such as “design-build pedagogy,” “experiential learning,” “hands-on prototyping,” “material experimentation,” and a “process-over-product” ethos. Reflective practices, notably “post-occupancy evaluation,” were deliberately incorporated to capture the critical feedback loops inherent in this approach.

- Live Project sources were selected for their focus on authentic client partnerships. Search parameters included “live project pedagogy,” “real-world briefs,” and “client-centred studio,” alongside emergent approaches to “digital co-design,” “iterative feedback,” and “co-production of knowledge.” The inclusion of works on “ethical frameworks” ensured comprehensive coverage of both professional and socio-ethical dimensions.

3.3. Materialising the Socius

This concluding procedure involves synthesising key theoretical constructs into core attributes that define each model, highlighting shared principles and model-specific areas of emphasis. The two lines of inquiry blend into an integrated studio pedagogical approach that leverages the unique possibilities of socially engaged pedagogies; “Community Design,” which brings place-based commitment through participatory workshops, stakeholder negotiation, and equity-focused research; “Design-Build,” which adds a hands-on prototyping and material experimentation dimension, training students to translate social needs into tangible interventions and to iterate through feedback loops; and “Live Project,” which contributes authentic client-centred briefs and ethical co-production of knowledge, ensuring that real-world limits and professional protocols guide the design process. In essence, these proposals are incorporated into a socius-centric approach which aims to equip future architects with the theoretical grounding, technical fluency, and civic-minded praxis needed to foster transformative learning, build community agency, and strengthen social resilience in the built environment.

3.4. Interlocking Methodological Phases and Procedures

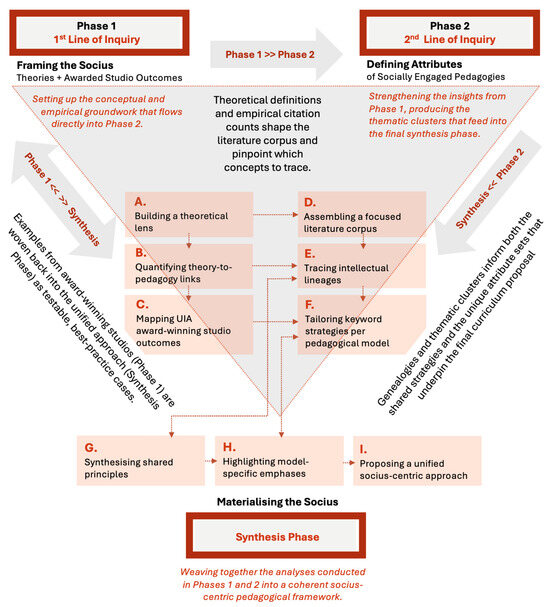

Capturing the approach to inquiry into methodological phases and procedures, the investigation involves two key phases representing the two lines of inquiry. A third phase is envisaged to articulate how the socius could be materialised in architectural pedagogy (Figure 1). Each of the two key phases includes sub procedures as outlined in the following sequence:

Figure 1.

A multilayered approach to inquiry designed in two key investigation phases and a synthesis phase to map, characterise, operationalise, and materialise the socius in architectural pedagogy.

- Phase 1: 1st Line of Inquiry—Framing the Socius

This phase sets up the conceptual and empirical groundwork that flows directly into Phase 2, and includes the following:

- A.

- Building a theoretical lens: This procedure involved gathering key theories (e.g., relational ontology, critical constructivism, experiential learning, dialogic pedagogy, reflective practice, and decolonial thought) and then utilising these theories to define the “socius” as the organising concept of the study.

- B.

- Quantifying theory-to-pedagogy links: Thirteen theories were identified; the procedure involved conducting a Google Scholar search and then pairing the search results with “Community Design,” “Design-Build,” and “Live Project” pedagogies in architecture. The procedure includes visualising the counts in a grouped bar chart to show which theories are most cited in each studio model.

- C.

- Mapping UIA award-winning studio outcomes: This procedure involved analysing seven UIA Innovation in Architectural Education-awarded studio outcomes (2019–2023), mapping the theoretical foundation to these outcomes, and coding each project for participatory workflows, interdisciplinary alliances, and analogue/digital methods. The procedure also included identifying how they embed social, cultural, and political dynamics in studio teaching.

- Phase 2: 2nd Line of Inquiry—Defining Attributes of Socially Engaged Pedagogical Models

This phase refines and heightens the insights from Phase 1, producing the thematic clusters that feed into the final synthesis phase, and includes the following:

- D.

- Assembling the focused literature corpus: This procedure encompassed collecting more than 200 peer-reviewed articles from Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. This was followed by filtering down the most relevant to 87 key publications (30 Community Design, 29 Design–Build, 28 Live Project).

- E.

- Tracing intellectual lineages: The procedure involved performing co-citation network analysis to reveal the scholarly genealogy of each of the three pedagogical models. This included utilising keyword hit counts (rounded) and year-range filters to gauge when core concepts first emerged.

- F.

- Tailoring keyword strategies per pedagogical model: This procedure included linking each pedagogical model to associated primary keywords: Community Design was associated with “community participation,” “charrettes,” and “equity in design”; Design–Build was associated with “hands-on prototyping,” “post-occupancy evaluation,” and “process-over-product”; and Live Project was associated with “real-world briefs,” “client-centred studio,” and “ethical frameworks,”

- Synthesis Phase—Materialising the Socius

This synthesis phase weaves together the analyses conducted in Phases 1 and 2 into a coherent pedagogical framework, and includes the following:

- G.

- Synthesising shared principles: This procedure included identifying cross-cutting strategies such as situating design in daily life, co-creation, reflection–action loops, and systemic impact.

- H.

- Highlighting model-specific emphases: This process involved critical identification of specific areas of focus for each of the three pedagogical models. Community Design focus is on place-based workshops, stakeholder negotiation, and social-justice research; Design–Build focus is on full-scale prototyping, material experimentation, and iterative feedback; and Live Project focus is on authentic client briefs, professional protocols, and ethical co-production of knowledge.

- I.

- Proposing a unified socius-centric approach: This process captured a conceptual integration of insights into the way in which the socius can be integrated into architectural pedagogy. This includes situating architecture in lived social systems; cultivating reciprocal agency; linking critical reflection to material change; and establishing crosscutting modes for integrating the socius.

Notably, the research process was not linear but involved feedback and feedforward aspects: Theories identified in A. guided the article selection in D.; citation patterns in B. shaped which lineages to trace in E.; and studio outcomes analysed in C. informed keyword choices in F. Likewise, the intellectual genealogy uncovered in E. underpinned the development and conceptualisation of the shared principles in G. The mode-by-model attributes identified in F. formed the basis for model specific emphases in H.

4. Theoretical Foundations for a Socius-Centric Pedagogy in Architecture

A conscious engagement with the socius demands rejecting binary notions of autonomy versus heteronomy, and instead embracing Althusser’s concept of relative autonomy, which locates architecture within a “complex formation” of interlinking social, economic, and political practices [23,24]. This position acknowledges that, while architectural culture operates according to its own internal logics and developmental rhythms, it remains strongly bound to broader structural forces of dominance and dependency [25]. Recognising this dialectic enables pedagogy to calibrate design methodologies in ways that both respect the discipline’s singular capacities and harness its potential to provoke socio-political transformation.

Central to the socius is the understanding that space itself is a product of social processes, a social construct, rather than a neutral milieu for architectural intervention or for filling a physical void. Lefebvre’s triadic conception on the production of space, which encompasses everyday practices, representational artefacts, and lived experiences, reveals how spatial forms both shape, and are shaped by, power relations and ideological currents [26,27]. Foucault’s analyses of spatial discipline further sensitise educators to how studio configurations, pedagogical routines, and assessment regimes implicitly regulate behaviour and reinforce hegemonic structures [22,28]. Together, these theories enable educators to engage critically with the socio-spatial underpinnings of designing both learning and the environments that accommodate it.

The key implication of these theories in architectural pedagogy is that it must be viewed as a crucible for the co-construction of student agency, identity, and professional formation within a structured “field” of norms and hierarchies, as theorised by Bourdieu [29,30,31]. The theory of “Structuration” further insinuates this reciprocity, delineating how studio conventions are both reproduced and contested through individual agency [22,32]. Within these dynamics, educators can design learning experiences that democratise access to disciplinary capital and foster inclusive, reflexive modes of professional formation [33].

Engaging with the socius entails adopting pedagogies that prioritise dialogue, critique, and experiential knowledge. Freire’s critical pedagogy emphasises the dialogic exchange and co-construction of knowledge, thus empowering students to critically examine power structures and pursue social justice [34,35]. Complementarily, Dewey’s experiential learning framework situates professional judgement within iterative cycles of action and reflection, which Schön later conceptualised as “reflection-in-action” and “reflection-on-action” [36,37,38]. The integration of hands-on workshops, community charrettes, and reflective debriefs thus becomes indispensable for cultivating both technical judgement and socio-political awareness [39].

Adding theoretical depth to the foundations of the socius, Latour’s Actor–Network Theory (ANT) can be utilised. ANT is a theory which argues, and rightly so, that human and non-human actors form shifting networks of relationships that define contexts, situations, and determine outcomes [40]. As a constructivist approach, it maintains that society, organisations, ideas, and other key elements are shaped by the interactions between actors in diverse networks rather than having inherent fixed structures or meanings. ANT can be conceptualised to reconceive the studio as an assemblage of human and non-human actors ranging from residents and students to digital platforms and material artefacts, each utilising agency in the co-creation of design outcomes [40,41]. This ecological understanding is broadened and enriched by postcolonial and decolonial lenses that challenge Eurocentric dominance and promote pluri-epistemologies, thereby potentially deconstructing colonial legacies in architectural pedagogy [2,42,43].

Advancing this line of conceptualisation, the New Materialist approach enables a further lens since it rejects the traditional dualistic binaries, or binary oppositions, and polarities between humans and non-humans, nature and culture, and subject and object. Instead, it places emphasis on dynamic relationships and processes, and asserts the agency of matter and its capacity to shape itself and influence its physical and social context, including human experience. In essence, New Materialist thought attributes agency to matter itself, encouraging pedagogies that recognise materials, sites, and infrastructures as active participants in the socio-spatial dialogue [44].

Collectively, these theoretical stances establish a rigorous foundation for analysing and integrating the socius across diverse design studio pedagogical models, ensuring that education remains both critically substantiated and socially responsive. They reveal how space, power, and identity co-produce architectural knowledge within institutional and social constraints. Theories such as Althusser’s relative autonomy and the Actor–Network Theory further challenge traditional binaries, promoting an understanding of architecture as a dynamic interplay of human and non-human agents. Pedagogies inspired by Freire, Dewey, and Schön prioritise dialogue, reflection, and experiential learning to cultivate critical awareness and agency. This fusion of theories empowers educators to design inclusive, reflexive, and context-sensitive curricula that equip future professionals to navigate and reshape the sociopolitical forces embedded in architectural practice and the context within which it operates.

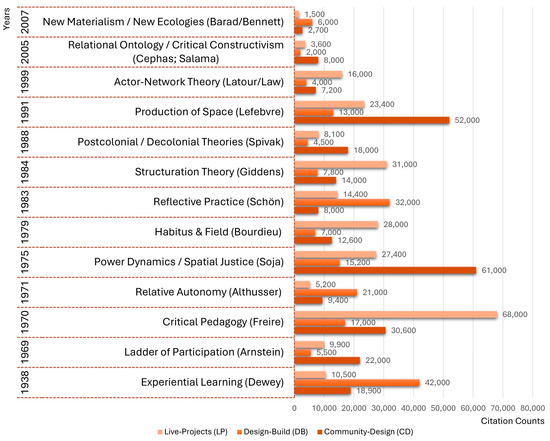

Verifying which theoretical frameworks underpin which pedagogies in the literature was an essential procedure (Figure 2). Therefore, theory-to-pedagogy alignments have been quantified through citation counts, moving beyond intuitive associations to provide empirical evidence on which conceptual lenses drive social, cultural, and political engagement in each of the three models. This ensures that the subsequent characterisation of each studio teaching model reflects prevailing scholarly emphasis.

Figure 2.

Comparative citation frequencies of key theoretical frameworks across Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project pedagogies, as revealed by the bibliometric analysis.

The citation and association patterns reveal distinct theoretical commitments and untapped opportunities. The strong association of Community Design and Lefebvre’s Production of Space (≈52 K) and power-analysis frameworks (≈61 K) confirms its deep interest in interrogating who shapes and is shaped by the built environment, “whose built environment”. Yet, its relatively sparse engagement with Actor–Network Theory (~6 K) suggests an opening to amplify the role of material and non-human actors in participatory processes. Design–Build’s identity as a craft-centred pedagogy is, likewise, evident in its strong alignment with Dewey’s Experiential Learning (≈42 K) and Schön’s Reflective Practice (≈32 K), accentuating the primacy of “making-as-thinking” and real-time adaptation. However, the lighter presence of decolonial theories (~18 K) and New Materialism (~6 K) points to fertile ground for critically examining colonial legacies in construction methods and recognising active agency of the matter.

Live Project pedagogy is firmly grounded in Freire’s Critical Pedagogy (≈68 K), reflecting its focus on authentic briefs as arenas of power negotiation and professional agency. Yet, its moderate engagement with Relational Ontology (~8 K) and Actor–Network Theory (~16 K) indicates growing interest in networked collaborations, but also an invitation to systematically weave these lenses into its “liveness,” capturing the full interplay of people, institutions, and technologies. Collectively, these findings map the theoretical tenets of each pedagogical model as well as illuminate strategic intersections such as integrating New Materialist insights into community workshops or actor–network awareness into live briefs, which can deepen the capacity of all three pedagogies to further integrate the socius in its fullest sense.

5. Framing the Socius Through Award-Winning Pedagogical Innovations

Building on the preceding theoretical lenses, seven relevant award-winning studio outcomes of the UIA Award for Innovation in Architectural Education are analysed to demonstrate concrete articulations of the socius within contemporary architectural pedagogy. Inaugurated in November 2019 by the UIA Education Commission, the award aims to recognise and promote exemplary teaching methods that promote sustainability, social equity, and cultural responsiveness across diverse contexts.

Studio outcomes are evaluated based on their capacity to integrate societal and environmental imperatives into pedagogical practice. The analysis of the awarded projects is predicated on three thematic imperatives that include community co-creation, collaborative networks, and the integration of global and indigenous perspectives and material agency, each revealing distinct strategies for embedding social, cultural, and political dynamics at the core of design education [45,46].

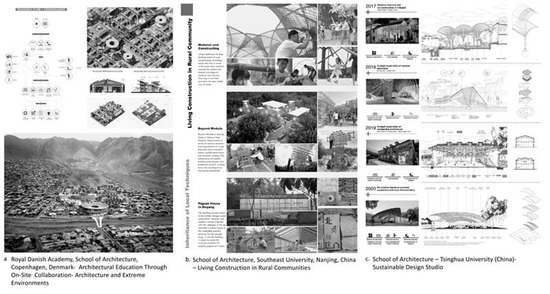

The inaugural 2019–2021 cycle resulted in three awarded studio outcomes; a field-based curriculum at the Royal Danish Academy that embeds on-site collaboration in extreme environments; Southeast University’s multi-year MArch programme in Nanjing that unites cultural, social, and environmental learning through rural community construction; and Tsinghua University’s Sustainable Design Studio, which emphasises “learning by doing” through co-developing analogue and digital interventions with local stakeholders (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Representative posters for awarded studio outcomes (2019–2021) that integrate one or more aspects of the Socius. Source: Adapted from [45] (See Supplementary File Figure S1 for larger scale images of these panels).

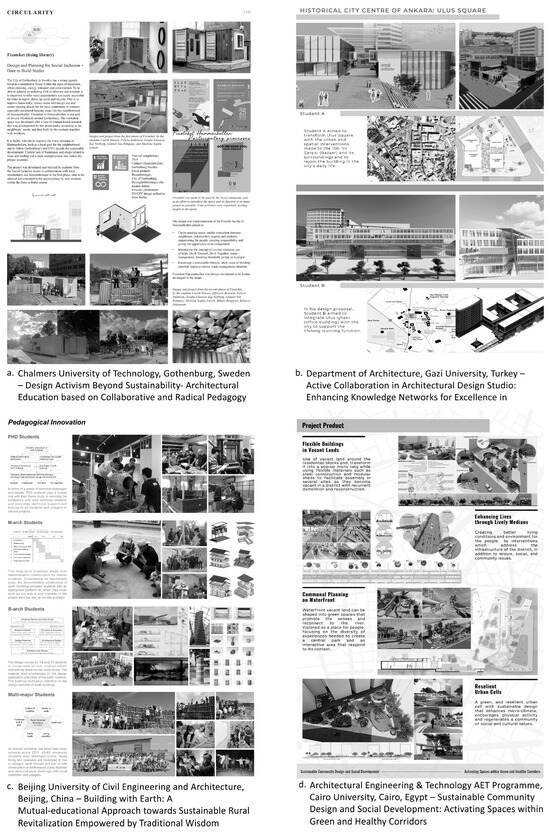

In its 2021–2023 cycle, the award deepened its commitment to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), broadened its assessment criteria to stress interdisciplinary collaboration, and extended to demonstrable regional impact [47,48]. In Sweden, Chalmers University of Technology’s “Design Activism Beyond Sustainability” pioneered a hyper-local, experiential pedagogy that challenges students to co-create interventions addressing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), weaving together theoretical inquiry, grassroots activism, and hands-on practice. In Turkey at Gazi University, the “Active Collaboration in Architectural Design Studio” reframes learning networks by integrating community service, building retrofits, and cross-scale sustainability strategies, ranging from neighbourhood greening to urban policy proposals.

In China, Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture launched “Building with Earth,” a mutual-educational programme where scholars and villagers jointly prototype rammed-earth systems through participatory workshops, reviving traditional techniques while fostering shared expertise. In Egypt, Cairo University’s “Sustainable Community Design and Social Development” studio employs action-research and multi-modal engagement tools to equip students with the skills to develop green, health-focused corridors in rapidly evolving and contested urban contexts (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Representative posters for awarded studio outcomes (2021–2023) that integrate one or more aspects of the Socius. Source: Adapted from [45] (See Supplementary File Figure S2 for larger scale images of these panels).

5.1. Mapping Theoretical Foundations for a Socius-Centric Pedagogy to the UIA-Awarded Studios Outcomes

In critically conceptualising how the UIA-awarded studio outcomes echoed the identified theoretical foundations for a socius-centric pedagogy in architecture, it can be argued that, collectively, the seven awarded outcomes legitimate the socius both as a didactic milieu and a cornerstone in which theory and practice unite. Across these outcomes, Althusser’s relative autonomy [23,24] emerges most notably in Tsinghua University’s Sustainable Design Studio. In this context, students navigate the internal logics of the discipline (“making-as-thinking”) while remaining entangled in villagers’ material and social needs, negotiating timber choices and labour roles through a site-specific reconciliation between autonomous design reasoning and external socio-economic forces.

Lefebvre’s triadic production of space [26,27] resonates with Chalmers University’s’ studio on Design Activism and Cairo University’s Garbage City intervention, where participatory mapping workshops and prototypes capture everyday practices and lived experiences. Inviting residents to co-author pavilions or shaded walkways, these interventions unveil how representational artefacts (plans, drawings) and spatial practice (charrettes, builds) co-produce contested urban environments, consequently, strengthening spatial justice imperatives.

Foucault’s insights into disciplinary organisation [28] seem to surface in Gazi University’s courtyard house restoration, where the formality of the studio, including archival research and municipal review panels, both disciplines and liberates students, elucidating how power circulates through pedagogical routines. Yet, reframing the role of bureaucrats and NGOs as coauthors, the studio disrupts or resituates hierarchical knowledge flows, exemplifying the duality of Structuration [32], where norms are reproduced but also contested.

The dialogic pedagogy of Freire [34,35], the experiential learning of Dewey [36], and the reflection in action of Schön [38] appear to represent Southeast University’s rural co-construction programme, where the iterative aspect manifests through photogrammetry sessions and wetland restorations which become sites of critical inquiry and reciprocal learning. In this respect, the “teacher” and the “villager” roles blur, enabling student agency and communal ownership to emerge.

Strongly, Actor–Network Theory [40] and New Materialism [44] seem to converge in the Royal Danish Academy’s Arctic shelters and Beijing’s rammed earth schools. Questions on potential design responses, GIS analyses, and bamboo-reinforced clay walls, which are non-human actors, employ agency, stimulating human actors to reconsider knowledge systems. Elevating and giving primacy to personal/human epistemologies alongside digital tools, and situating earth itself as an active collaborator, these studio outcomes actualise and manifest a materially engaging design teaching practice. Palpably, the thread of postcolonial and decolonial lenses [42] is evident through every project in a manner that challenges Eurocentric canons: the “earth school” in China revives indigenous craft; the framing of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Sweden and India [48] mobilises global justice discourses at the local scale.

It is palpable that there is a link between the UIA-awarded studio outcomes and the identified theoretical foundations towards socius-centric pedagogy in architecture. These awarded outcomes do not simply demonstrate theoretical frames, but they perform and actualise them; they integrate important polarities including autonomy and dependency, power and critique, and human and non-human agency into pedagogical assemblages that reconfigure architecture and its teaching as a socio-spatial praxis where theory is enacted, embodied, or realised through design and planning activities.

5.2. Strengthening Community Engagement and Co-Creation

The hyper-local studio, Design Activism Beyond Sustainability, at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, empowers students as “change-makers,” guiding them through a five-stage co-creation methodology implemented in two sites: co-initiation, co-analysis, co-design, co-implementation, and co-evaluation. Tethering each phase to one or more of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), participants collaborate with residents of marginalised suburbs in Gothenburg and informal settlements in Mumbai. Through joint mapping workshops, participatory charrettes, and co-constructed lightweight pavilions, the studio instantiates Freirean dialogic and demonstrates how targeted interventions can advance gender equity, institutional transparency, and spatial justice [49].

Operating as a Live Project studio in Manshiyet Naser’s “Garbage City,” the Sustainable Community Design and Social Development programme at Cairo University, Egypt, employs action-research and Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation to address urban heat islands and public health deficits. Students conduct stakeholder interviews, facilitate role-playing negotiations with waste-picker cooperatives, and fabricate full-scale green-corridor prototypes. Iterative feedback loops comprising model-based community reviews and digital surveys ensure that designs for shaded walkways and bioswale systems reflect local priorities, thereby translating Deweyan experiential learning into measurable social impact [50].

5.3. Fostering Collaborative Networks and Adaptive Practice

Bridging academia, local authorities, and rural communities outside Beijing, the “learning-by-doing” Sustainable Design Studio at Tsinghua University, China, mobilises Design–Build projects such as “The Wall: Children’s Restaurant,” a co-constructed timber pavilion, and “Road to Light,” a solar-powered pathway network. Integrating vernacular rammed-earth techniques and on-site digital fabrication, the studio exemplifies architecture’s relative autonomy while embedding it within socio-material contexts. Participating villagers and students jointly negotiate material choices and labour division, thereby co-authoring sustainable infrastructures that respond to region-specific ecological and social needs [51].

Anchored in Ankara’s historic Ulus District, the Active Collaboration in Architectural Design Studio at Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey, forges formal partnerships with the Metropolitan Municipality, the Chamber of Architects, and local NGOs. Tasked with revitalising Ottoman-era courtyard houses, student teams undertake archival research, conduct building assessments, and develop adaptive reuse proposals, ranging from micro-enterprise hubs to cultural heritage trails. Public exhibitions and municipal review panels provide real-time critique, reinforcing an Actor–Network Theory approach through which residents, bureaucrats, and students collectively shape the evolving urban fabric [52].

5.4. Integrating Global Challenges, Indigenous Perspectives, and Material Agency

Deployed across Greenland’s coastal hamlets, the field-based studio Architecture and Extreme Environments at the Royal Danish Academy, Copenhagen, Denmark, immerses students in Arctic conditions to co-design modular shelters that address permafrost thaw, energy scarcity, and food insecurity. Pairing GIS-driven environmental analyses with Inuit knowledge workshops, the studio forges contextually attuned prototypes such as snow protections for safe travel and low-impact marine food hubs. These interventions engage a diverse number of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) while reaffirming architecture’s role in mediating human–nonhuman networks and honouring Indigenous epistemologies [53].

Spanning ten villages in Jiangsu Province, the multi-year MArch programme, Living Construction in Rural Communities, at Southeast University, Nanjing, China, integrates architectural design, agricultural cooperatives, and heritage preservation. Students and villagers collaborate on timber-frame restoration, wetland remediation, and the construction of folk-art festival pavilions. Employing photogrammetric surveys and participatory mapping, the studio documents pre-existing settlement patterns and agricultural cycles, ensuring interventions such as raised boardwalks and communal granaries strengthen both ecological function and social cohesion [54].

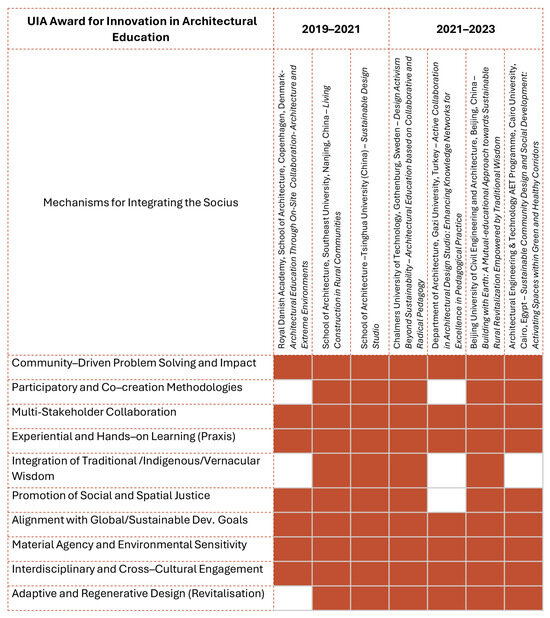

Operating across three rural villages in Shaanxi Province, the Building with Earth programme at the Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Beijing, China, establishes “earth schools” where students, teaching staff, and villagers co-develop seismic-resistant rammed-earth wall systems. Through iterative prototyping, combining bamboo reinforcement, local clay chemistry analysis, and communal build days, the initiative actualises New Materialist principles of matter’s agency. The resulting community centre in Liujia exemplifies a “Chuan Cheng” pedagogical model, wherein reciprocal teaching–learning restores cultural esteem in traditional crafts and improves villagers’ livelihoods [55]. Positioned as a visual synthesis, the following matrix delineates how each awarded studio outcome enacts distinct dimensions of the socius within its pedagogical approach (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The mechanisms implemented by the seven awarded studio outcomes which manifest the core concepts of the socius.

Through a systematic mapping of integration points from community-driven problem framing and co-design methods to the incorporation of indigenous systems and the advancement of spatial justice, the matrix elucidates both singular strengths and collective commitments across the seven exemplar initiatives. By visually uniting these diverse strategies under a shared schema, the matrix reveals the multifaceted modalities through which contemporary architectural pedagogy aims to cultivate socially engaged, environmentally attuned, and culturally responsive ways of practice.

6. Narrating the Qualities of Socially Engaged Pedagogies

In contemporary architectural education, Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project studios constitute discrete yet intersecting modes of socially engaged instruction. In each, the socius manifests through distinct mechanisms of collaboration, material engagement, and professional integration.

6.1. Community Design Pedagogy

Community Design pedagogy emanates from the recognition that local communities have long shaped their spatial fabrics, marketplaces, souqs, and village clusters through locally attuned traditions and resourceful adaptations [56,57,58]. Community Design emerged in the 1960s during civil rights movements, reframing architects as co-learners in service-learning contexts [59,60]. Grounded in Freirean and Deweyan theories, early approaches utilised narrative tools, design games, and participatory methods to support marginalised voices [61].

Community Design Centres institutionalised this ethos, offering pro bono services and embedding community narratives in design [62]. By the 1970s, charrettes and participatory planning gained academic acceptance, exemplified by Sanoff’s studios in North Carolina and UK-based studios [56,63]. The 1990s introduced formal accreditation of community engagement and critical discourse on tokenism [64]. NGOs and university-led studios fostered global partnerships [65]. In the 2000s, digital tools expanded participatory frameworks [66]. More recently, efforts emphasise decolonial approaches, climate justice, and design justice studios [42,67]. Today’s interest integrates AI, Indigenous knowledge, and tools for resilient, inclusive futures [68,69].

Within the Community Design pedagogical paradigm, the architect assumes the role of facilitator or advocate, rather than an autocratic designer, engaging side by side with residents to co-produce responsive interventions [1,22,64]. Originating in the participatory planning initiatives of the 1960s and the 1970s when civil rights movements catalysed community-empowerment frameworks, this model has diffused globally in response to rapid urbanisation and housing exigencies, offering a collaborative counterpoint to top-down development [70].

In applying the Community Design paradigm, students forge reciprocal alliances with rural or urban stakeholders, immersing themselves in oral histories, vernacular customs, and everyday spatial practices by convening participatory charrettes, “community mapping workshops,” and door-to-door interviews within local halls or marketplaces [34,56,71]. This discursive, process-and-product-oriented approach balances experiential engagement with Schönian reflection, exciting learners to negotiate budgetary constraints, material availabilities, and regulatory frameworks even as communities acquire access to professional expertise [37].

The tangible outputs in the form of co-authored masterplans, public-space interventions, tactical urban programmes, and prototype pavilions function as socially responsive artefacts and capacity-building exercises. While not all community design projects culminate in student-led construction, those that do seamlessly transition into Design–Build pedagogy. Still, the core objective remains: to foster critical awareness of power asymmetries, to utilise local resources and appropriate technologies, and to reaffirm that enduring design emerges through genuine collaboration rather than imposed expertise.

6.2. Design–Build Pedagogy

Design–Build pedagogy reconceives the studio as both laboratory and construction site, immersing students in the full lifecycle of built work, from conception through fabrication to post-occupancy evaluation [43,71,72]. It represents an outgrowth of 1960s community design experiments, which has matured over recent decades into a pedagogical movement that prioritises “learning by doing,” material experimentation, and iterative feedback loops [5,73].

Design–Build pedagogy emerged in the 1960s–1970s, shaped by Dewey’s “learning by doing” and the Bauhaus integration of art, craft, and technology [74,75,76]. Early studios shifted design inquiry to physical engagement through on-campus workshops and off-site mini-builds, reinforced by emerging CAD tools [77]. Charles Moore’s Pavilion Workshop and Yale’s Appalachia projects exemplified this hands-on, socially responsive model [78,79,80].

By the mid-1970s, Design–Build matured into semester-long studios where students managed project phases, from budgeting to construction, emphasising sustainability and community engagement [73,81]. In the 1990s, programmes such Auburn’s Rural Studio and Yale’s BUILD institutionalised this approach through iterative prototyping and greater community ties [82,83]. Studio 804 advanced sustainable design, while growing use of CAD/BIM expanded technical capabilities [84].

Post-2000, prefabrication, modular systems, and integrated BIM platforms became a standard, aligning environmental and social goals [85,86]. The 2010s introduced CNC, robotics, AR/VR, and comprehensive BIM workflows [87,88]. Today, Design–Build is digitally hybrid and equity-driven, integrating remote fabrication, real-time data, and community resilience as seen in many schools of architecture across North America as well as globally [89,90].

Central to Design–Build is the imperative that every student-generated concept be physically realised, whether as a small pavilion, an interior installation, or a full-scale urban intervention, so that design decisions can be empirically tested and refined in situ. This “tool-belt” pedagogy equips learners with technical proficiencies in framing, joinery, and site logistics, while concurrently cultivating empathy, communication, and social responsibility through directed collaboration with clients and community representatives.

The outputs vary and include functional structures, prototype furnishings, and participatory urban fixtures aimed to deliver direct benefit to community stakeholders. Although explicit political engagement may be less pronounced than in dedicated Community Design studios, many Design–Build programmes integrate stakeholder consultation and reflective post-occupancy evaluation to ensure alignment with genuine social needs and foster sustained impact. Through the act of building, students internalise that architectural insight arises as much from craftsmanship and material dialogue as from abstract ideation.

6.3. Live Project Pedagogy

Live Project pedagogy constitutes the most expansive framework for socially engaged studio work, situating design education squarely within professional praxis by engaging students with authentic client briefs under real-time constraints of budget, schedule, and stakeholder expectations [71,91].

Rising during the 1960s–1970s amid socio-political unrest, Live Project pedagogy reframed architectural education as a socially engaged practice [43,92]. Students collaborated with civic bodies to address urgent urban issues through participatory methods, emphasising process over polished outputs.

The University of Sheffield’s early Live Projects exemplified this shift, fostering local investment and integrated community knowledge [93]. By the 1980s–1990s, live projects were formalised into curricula and studio briefs, combining project management, participatory design, and sustainability, aided by emerging CAD technologies [94]. Partnerships with nonprofits and municipal agencies expanded scopes and strengthened student collaboration skills.

The mid-1990s marked a turning point as Live Project pedagogy gained institutional legitimacy. Standardised assessments, risk protocols, and stakeholder involvement from NGOs and professional bodies reinforced its rigour [43]. Technological advances enabled global collaborations, with initiatives like UniSA’s Live Projects Studio (1996) and Oxford Brookes’ Symposium (2001) codifying its ethical and theoretical basis. The 2010s saw global adoption, characterised by interdisciplinary teams, impact-assessment tools, and digital prototyping. Programmes at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT), Melbourne, Australia, and at Cornell University, New York, integrated Indigenous and real estate perspectives, while scholarship advanced evaluative methodologies [71,95]. More recently, in the 2020s, AI, VR, and remote models are defining a hybridised pedagogy, preserving “liveness” in virtual contexts [96,97,98]. Initiatives such as decolonising studios by the University of Cape Town (UCT), South Africa, and pandemic-era collaborations by Columbia University, New York, reaffirm their commitment to equity and social transformation [99].

Re-instating the participatory ethos of Community Design and the material rigour of Design–Build, this model transcends campus boundaries to bridge the perennial gulf between academic speculation and practice and community exigency [43]. Pedagogically, Live Projects immerse participants in negotiation, procurement, and regulatory compliance, while also fostering creative development. Collaboration with municipal agencies, non-profits, and grassroots organisations requires students to embed their conceptual strategies within executable contexts, balancing aesthetic aspirations against legal, financial, and user-centred imperatives [43]. This practice-ready orientation cultivates the professional competencies essential for ethical, socially responsive practice: this includes reflective dialogue, adaptive problem-solving, and collaborative leadership [71].

The spectrum of deliverables, ranging from built structures to design proposals, research monographs, and advocacy strategies, attests to the methodological hybridity of this model. While every Community Design and Design–Build initiative can be recast as a Live Project, so too do Live Projects incorporate analogue and digital workshops, or full-scale construction phases as dictated by context. In embracing such integrative hybridity, Live Project pedagogy forges a unified framework in which the socius is integrated through sustained, context-driven collaboration, thereby equipping graduates to navigate complex social fabrics.

6.4. Similarities and Differences Across the Three Socially Engaged Pedagogical Models

Despite their distinct emphases, Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project studios share a common commitment to integrating the socius by embedding design practice within real social contexts. Table 1 offers a comparison of the distinguishing features of the three socially engaged pedagogical models, highlighting their distinct emphases, outputs, stakeholder roles, temporal scales, and assessment challenges.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of key dimensions across Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project pedagogies.

Each model emphasises experiential learning, prioritising “learning by doing” and integrating continuous cycles of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action into its pedagogy. Students collaborate directly with non-academic partners, whether residents in charrettes, community members on built sites, or clients in professional briefs, co-producing knowledge and dismantling the traditional architect-as-expert hierarchy. Primarily, with different degrees of manifestations, all three models rely on iterative feedback processes, utilising pilot workshops, scaled mock-ups, or policy drafts to test, critique, and refine design solutions.

Despite the shared fundamentals, the three models diverge in emphasis and scale. On the one hand, Community Design studios prioritise co-design, social justice, decision making, generating neighbourhood master plans, and building schematics and public-space interventions through short, intensive workshops that engage residents as full collaborators. However, evaluating individual equity contributions can prove challenging. On the other hand, Design–Build studios focus on material experimentation and craft, producing full-scale pavilions and installations over multi-week building phases, where clients become hands-on co-builders. Still, uneven construction skills and logistical demands complicate assessment. Live Project pedagogy, by contrast, integrates professional practice into semester-long or multi-year engagements, tasking students with negotiating real budgets, regulatory approvals, and stakeholder interests to deliver diverse outcomes, ranging from built prototypes to policy briefs, and requiring a careful alignment of academic objectives with authentic deliverables.

7. Core Attributes of Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project Pedagogies

The keyword analysis reveals that there is an often-interchangeable use of terms across Community Design, Design–Build, and Live Project pedagogical models. It demonstrates how they closely overlap and how easily their defining characteristics can blur together in practice. This juxtaposition makes it imperative to articulate the core attributes of each model. Distinguishing the hallmark dimensions of Community Design (dialogic engagement and equity-centred co-production), Design–Build (“learning by making” through material experimentation and process-driven iteration), and Live Project (“liveness” of authentic client briefs and professional practice integration), educators can gain a particular vocabulary for their design studio teaching practices.

The clarity in identifying the salient characteristics of the three pedagogies ensures that teaching strategies, learning outcomes, and assessment criteria align directly with the unique purpose of each model, while also elucidating natural intersections where hybrid approaches can thrive. The identification of these core attributes provides a robust pathway for developing, implementing, and evaluating socially engaged architectural design studios that remain both focused and adaptable.

7.1. [PEARL] Community Design Pedagogy

Community Design pedagogy positions residents and community groups not as passive recipients but as co-designers, sharing authority over problem definition, visioning, and decision and solution-making. [PEARL] is an acronym conceptualised to capture the key qualities of the Community Design model (participatory and dialogic methods; equity lens and social justice; artefact and process integration; resourceful contextualism; learning through reflection). Core attributes include the following:

- [P]articipatory and Dialogic Methods: The model relies on facilitated charrettes and participatory mapping workshops to bring students and community members together in structured and interactive workshops. Using large-scale maps, physical models, and dot-voting exercises, these sessions feature local priorities and spatial narratives, ensuring that design emerges from lived experience rather than top-down assumptions [56,64]. This approach extends to the co-production of knowledge, in which design teams learn alongside residents, harvesting oral histories, everyday practices, and cultural insights to collaboratively shape project briefs and generate contextually relevant design options [100].

- [E]quity Lens and Social Justice: An equity and social justice lens underpins every phase of teaching/learning, actively addressing power imbalances by centring the voices of marginalised groups, including low-income families, racial minorities, and informal settlers. This commitment ensures that each design choice advances fairness, access, and representation, rather than perpetuating historical exclusions or reinforcing existing hierarchies [42].

- [A]rtifact and Process Integration: This attribute measures studio success in both the richness of stakeholder engagement and the quality of co-authored deliverables. The “journey” is quantified by metrics such as hours of dialogue and the diversity of perspectives heard, while the “artefact,” be it a neighbourhood master plan, a temporary plaza installation, or a strategic policy recommendation, serves as tangible proof of collaborative learning and community impact [101].

- [R]esourceful Contextualism: Context-sensitivity and local resourcefulness manifest through local principles in every design decision. Studios draw upon craft traditions, indigenous materials, and community-developed spatial logics, whether rammed earth, woven screens, or market-stall typologies, to reinforce cultural continuity and resource efficiency. This rootedness in local knowledge and practices ensures that interventions resonate with place and people [58,100].

- [L]earning through Reflection: Reflective praxis is woven into the studio through cycles of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. Students maintain reflective journals and participate in pause-and-probe sessions during workshops, enabling the real-time adaptation of methods and the consolidation of insights after each cycle. This continuous reflexivity deepens both conceptual understanding and practical skill development [36,38].

7.2. [SHAPE] Design–Build Pedagogy

The core orientation of Design–Build pedagogy leans towards “Learning by Making”, transforming the studio into a hands-on workshop where ideas are tested materially, and the act of construction is integral to design intelligence. [SHAPE] is an acronym conceptualised to capture the key qualities of the Design–Build model (service integration; hands-on experimentation; action–reflection; process-over-product ethos; and end-to-end teamwork). Core attributes include the following:

- [S]ervice Integration: Community service integration roots projects in under-resourced contexts, community centres, affordable housing prototypes, or public seating pavilions, highlighting the capacity of architecture in effecting positive social change. Focusing on tangible interventions that directly benefit local populations, studios reinforce the social responsibility at the heart of the design and building processes [59,72].

- [H]ands-on Experimentation: Design–Build studios immerse students in hands-on experiences with tools and materials, from sawing timber to mixing earthen plaster. Through these hands-on activities, participants develop a tactile understanding of structural behaviour, finish quality, and climatic performance, insights that directly inform subsequent design refinements and strengthen their material literacy [83,102].

- [A]ction-Reflection: Reflection-in-Action occurs through on-site critique sessions embedded in the process. As walls rise and roofs are framed, students pause to test spatial relationships with stakeholders, adjusting dimensions, material palettes, or circulation patterns in response to real-time observations. This in-the-moment reflection deepens their ability to adapt and refine designs under authentic conditions [38].

- [P]rocess-Over-Product Ethos: This attribute prioritises iterative prototyping over polished digital renderings. Studios emphasise successive full-scale mock-ups and pilot installations, gathering post-occupancy feedback to recalibrate form, detailing, and user interaction. This approach underscores the value of making as a means of discovery rather than the pursuit of a single finished artefact [73].

- [E]nd-to-End Teamwork: Collaborative teamwork and project management transform studios into end-to-end project delivery simulations. Student teams assume full responsibility for every phase, including cost estimating, grant writing, permit applications, and volunteer coordination, mirroring professional practice and cultivating leadership, communication, and organisational skills essential for real-world practice [73,84].

7.3. [CRISP] Live Project Pedagogy

Live Project Pedagogy places students at the nexus of academic research and professional practice by engaging them with real briefs, genuine clients, and the full complexity of built-environment projects. [CRISP] is an acronym conceived of to identify the key qualities of the Live Project model (constraints and contingencies; regulatory and professional practice integration; interdisciplinary and ethical frameworks; scalable hybrid toolkit; and plural outcome diversity). Core attributes include the following:

- [C]onstraints and Contingencies: The model embraces “liveness” by imposing authentic constraints on design work. Fixed budgets, regulatory approvals, stakeholder politics, and ongoing maintenance requirements all serve as non-negotiable parameters. These real-world contingencies enable students to reconcile idealised concepts with pragmatic realities, deepening their capacity to produce feasible, sustainable solutions under genuine professional conditions [43,71].

- [R]egulatory and Professional Practice Integration: This attribute brings contractual and regulatory competence into the curriculum. Students draft requests for proposals, negotiate scope changes with municipal clients, and coordinate with contractors, gaining fluency in procurement processes, liability management, and comprehensive design documentation. This integration mirrors actual practice and prepares students for the administrative dimensions of professional work [43].

- [I]nterdisciplinary and Ethical Frameworks: These frameworks ground Live Project studios in critical and decolonial mindsets. Ethical guidelines, decolonial methodologies, and Actor–Network Theory sensitise participants to power dynamics among universities, communities, and industry. Examining such relationships, educators can ensure that design interventions uphold justice, equity, and mutual respect across all stakeholder groups [42].

- [S]calable Hybrid Toolkit: A hybrid methodological toolkit enables selecting and combining techniques dynamically within a single semester. Depending on the project scale and context, studios may run community charrettes, develop virtual reality prototypes, conduct participatory GIS mapping, and build physical mock-ups. This adaptability creates an amply layered pedagogical experience, equipping students with a broad array of engagement and design tools [2].

- [P]lural Outcome Diversity: This attribute reflects the multifaceted nature of Live Project deliverables. Beyond built prototypes, studios may produce policy briefs, research monographs, maintenance manuals, or community-training toolkits. This variety demonstrates the many roles that design can play in catalysing social and environmental change, reinforcing the expansive impact of Live Project pedagogy [71].

Despite the relative differences and areas of emphasis, all three models integrate the socius, which are the dynamic dialectics of social, cultural, and political forces. This is achieved by focusing on genuine community engagement, fostering reflexive practice, and translating design knowledge and action into meaningful societal impact.

8. Discussion and Reflective Critique: Materialising the Socius in Architectural Design Studio Pedagogy

All three socially engaged studio models encounter distinct but overlapping challenges. Despite the commitment to social responsibility in the Community Design pedagogical model, it is often found that genuine engagement outlasts a semester’s scope, leading to shifting project goals and logistical strain [103]. Short-term interventions can unintentionally become “design tourism,” risking ethical pitfalls and community disillusionment [104], while tight budgets and an emphasis on immediate needs may sideline more speculative or technical explorations [105]. Furthermore, the deeply collaborative and emotionally intense nature of this model complicates individual assessment and places substantial emotional labour on students [106].

Design–Build pedagogy delivers invaluable hands-on experience but demands rigorous safety protocols, insurance, and significant oversight, all of which consume time and resources [107]. Constraints of budget, student skill levels, and safety often limit projects to small-scale builds, reducing exposure to complex structural or detailing challenges [108]. The intense focus on construction can overshadow conceptual design work, and varying construction proficiencies can lead to unequal learning outcomes. Public visibility of build failures further heightens pressure on students, academics, and institutions.

Live Project studios immerse students in authentic professional conditions, but are highly vulnerable to client volatility, brief changes, decision delays, or cancellations, which can derail learning and morale [109]. Unrealistic expectations may exploit student labour without commensurate pedagogical benefit or compensation [106], while confidentiality and intellectual-property concerns limit academic openness [110]. Constrained budgets and narrowly defined briefs can suppress creative experimentation, and external variables complicate fair assessment [111]. Academics and tutors often shoulder substantial administrative burdens in client liaison and contract management, roles that extend well beyond traditional academic duties.

Despite these critiques, following the characterisation of the defining attributes of each model, this discussion extends to explore how the three pedagogical models integrate the socius through four interrelated strategies. First, they situate design learning within the fabric of everyday community life; second, they transform stakeholders into genuine co-creators; third, they ensure that critical reflection directly informs tangible outcomes; and fourth, they catalyse broader social and institutional transformations that extend well beyond individual projects.

Situating Architecture in Lived Social Systems: All three pedagogies go beyond the isolated hypothetical project in traditional studios by placing design work directly within everyday community life. In Community Design, students step into users’ routines, attending local events, sharing neighbourhood spaces, and centring design activities in community hubs so that every mapping exercise and charrette unfolds within the rhythms of daily life. Design–Build builds within that milieu, staging construction on-site so that students shop at local suppliers, coordinate around communal schedules, and test prototypes in the very environment they will serve. Live Project pedagogy extends this further by convening critiques, workshops, and even client meetings in public centres, weaving academic inquiry into municipal processes and transforming the studio into an actual social node rather than a campus enclave.

Cultivating Reciprocal Agency: Each model recasts architects and community members as co-authors. Community Design studios allocate authority through participatory mapping, co-drafted briefs, and consensus workshops, ensuring that local knowledge guides every design decision. Design–Build studios share the building process itself, clients red-line mock-ups, and volunteers co-construct elements. All contributions are formally documented, so that authorship becomes collective. Live Project studios institutionalise this reciprocity at a larger scale, granting community stakeholders equal votes in design selection, co-writing maintenance guides, and creating joint memoranda of understanding. Across all three studio models, design ceases to be a one-way transfer of expertise and becomes a negotiated act rooted in mutual respect.

Linking Critical Reflection to Material Change: Reflection in these studios is inseparable from tangible outcomes. Community Design embeds real-time feedback loops through iterative workshops and post-implementation surveys that inform both the next design iteration and ongoing advocacy. Design–Build integrates post-occupancy evaluations and build-phase critiques, allowing hands-on insights about performance, comfort, and durability to directly shape subsequent prototypes. Live project studios integrate reflection into policy and practice: client interviews, usage data, and field journals prompt mid-project course corrections and, where appropriate, inform the development of new municipal guidelines or scaled-up interventions. In every approach, critical insight gains full value only when it translates into concrete design adjustments, operational policies, or phased rollouts.