1. Introduction

1.1. Background

In recent years, architectural drawing has gradually become an important subject of discussion in both architectural research and the field of art. Unlike traditional architectural drafting, architectural drawing not only serves to convey architectural information but also demonstrates unique value in artistic expression, emotional communication, and cultural representation. As architectural drawing has evolved from a design aid to an independent visual language and artistic form, its research methods and evaluation systems urgently need improvement. Most current studies focus on the technical analysis and historical evolution of architectural drawing or explore its role in the architectural design process, but they lack systematic analysis of architectural drawing as an independent visual art form.

In today’s “image era”, where information dissemination methods are constantly changing, the rapid development of visual culture has driven the diversification of architectural drawing techniques [

1]. The transition from print media to digital media has introduced new characteristics to the creation and dissemination of architectural drawings. For example, the popularity of square compositions and symmetrical images on social media platforms such as Instagram and Pinterest have influenced the composition of architectural images [

2]. Meanwhile, the widespread use of computer software such as Photoshop, Rhino, and AutoCAD has improved the precision of architectural drawings but has also diminished the tactile quality and texture of hand-drawn works, leading to the gradual disappearance of some traditional techniques [

3].

Although academic research on architectural drawing has increased in recent years, most studies focus on technical aspects and lack systematic interpretation of its artistic and cultural significance. Moreover, architectural drawings are often used as key visual elements in architectural competitions, bids, exhibitions, and publications, but the evaluation criteria vary widely and often rely on subjective judgments rather than objective theoretical frameworks [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Therefore, the reception and interpretation of architectural drawings in different cultural contexts, as well as how to evaluate their artistic value, remain important topics for further research.

1.2. Objectives

This study aims to fill the research gap by introducing a new analytical perspective for evaluating architectural drawing. Integrating iconological analysis, symbolism studies, and visual culture theory, this research employs case studies and interview analysis to examine the visual language, cultural contexts, and interpretative frameworks of architectural drawing across different audiences. The objective is to reveal the interaction between visual representation, information transmission, and artistic value in architectural drawings. Specifically, this study addresses the following key questions: (1) How do architectural drawings balance between architectural drafting and artistic expression? (2) How are visual symbols in architectural drawings interpreted across different cultural contexts? (3) Can a multi-dimensional analytical model provide an objective framework for evaluating architectural drawings?

This study selects the works of four Chinese and Japanese architectural architects [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] and attempts to establish an objective evaluation standard for architectural drawing through semiotic and iconological approaches. Unlike existing studies that mainly focus on technical analysis or the role of architectural drawing as a design tool, this study emphasizes the balance between functionality and artistic value in architectural drawing. It also highlights the role of architectural drawing in cultural heritage, historical narratives, and social representation, aiming to provide new perspectives for architecture, visual arts, and cultural studies and to offer theoretical support for the future education, dissemination, and application of architectural drawing.

2. Literature Review

Architectural drawing, as an essential part of architectural design, plays a critical role from assisting architects in conceptualizing ideas through sketches to visually presenting the final design. Since the 1990s, with the widespread adoption of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) and digital modeling technologies, the use of architectural drawings to present final design schemes has gradually declined [

23]. However, the dual characteristics of architectural drawing—functionality (as a means of conveying architectural designs) and artistic value (as a medium for aesthetic appreciation and critical reflection)—have allowed it to evolve from a tool within architectural design to an independent form of art. Evaluating the artistic value of architectural drawing, therefore, remains an area worthy of further exploration. While these studies have explored architectural drawing from different dimensions, research that integrates both the functionality and artistic value of architectural drawing remains limited. Existing analytical frameworks also have certain limitations. Therefore, this study aims to review these works and propose an analytical framework that integrates both functionality and artistic value for evaluating architectural drawing.

The current literature on architectural drawing primarily focuses on three aspects: the teaching of drawing techniques, historical documentation and case studies, and analytical methods for architectural imagery. While these studies have explored architectural drawing from various perspectives, research that integrates both the functionality and artistic value of architectural drawing remains limited. Existing analytical frameworks also present certain limitations. Therefore, this study aims to review these works and propose an analytical framework that balances functionality and artistic value in architectural drawing.

2.1. Teaching of Architectural Drawing Techniques

Traditional architectural drawing instruction primarily focuses on functionality principles such as perspective, angles, proportions, and specific symbols, as well as how to represent architectural components and materials in drawing, ensuring accurate expression of architectural designs on a two-dimensional plane for effective communication of architectural information [

23].

Some teaching materials on architectural rendering techniques have started to explore how to enhance artistic expression in drawings, such as the narrativity of background illustrations [

24,

25]. In addition, design principles commonly used in graphic design, such as white space, contrast, and layered information, are often referenced in architectural drawing instruction [

26]. However, these studies mainly emphasize drawing techniques and rarely integrate both functionality and artistic expression in architectural drawing.

In recent years, some research has explored the advantages of hand-drawn architectural drawings and encouraged students to adopt architectural drawing as the primary visual representation in architectural design proposals [

8,

11]. One study suggested that architectural drawing can incorporate compositional techniques, color applications, and rhetorical methods from other art forms to enhance visual expression.

2.2. Historical Documentation of Architectural Drawing

Studies on the historical documentation of architectural drawing mainly focus on compiling works by architects and design teams from different countries and historical periods [

7,

27,

28,

29,

30]. However, these works primarily involve the collection of illustrations and chronological documentation, with the main focus of articles being on architects’ personal styles and architectural design schemes [

27,

28], rather than the analysis and evaluation of architectural drawing as an expressive medium. There is also a lack of systematic comparison of different architects’ drawing styles. Overall, although existing studies have systematically reviewed the historical development of architectural drawing, research on architectural drawing as an independent form of artistic expression remains limited.

2.3. Analytical Studies on Architectural Imagery

Existing studies on architectural imagery analysis mainly consider architectural drawing as part of architectural imagery. These methods explain the functionality and artistic value of architectural drawing to varying degrees, but they also have certain limitations in practical applications [

1,

2,

3,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Since the concept of architectural imagery covers a broad scope, its analysis often leans toward sociology and communication studies. Discussions on architectural drawing often adopt methods from Panofsky’s iconological studies or Wölfflin’s five pairs of stylistic principles [

34]. Architectural drawing primarily serves to express spatial design concepts rather than merely being a narrative or symbolic visual representation. Thus, its content may not fully conform to Panofsky’s three-level analysis structure [

35]. Architectural drawing within the iconological framework typically can only be analyzed at the first level (pre-iconography) and the third level (iconology), while the second level (iconography) is often absent, limiting its interpretative dimensions in specific cultural contexts. These methods are widely applied in studies of symbolic meanings in Western painting, but they face challenges when analyzing architectural drawings in East Asian countries such as China and Japan due to differences in cultural backgrounds and artistic traditions. Some studies have explored the artistic value of architectural drawing, but they often aim to enhance the artistic direction of the final architectural design rather than focusing on architectural drawing itself [

36,

37].

Other studies have examined architectural drawings in architectural competitions, but these discussions mainly regard them as primary visual representations in proposals with different themes, confined within the competition’s evaluation framework [

4]. The focus is often on clarity of information, visual accessibility, and content readability rather than on artistic value. Some research has explored post-construction architectural drawings as a form of critical reflection, balancing functionality and artistic value [

5]. However, this method has mainly been applied by architect Koshima Yusuke, and its general applicability to other architects and works remains unclear.

2.4. Research Gap and Research Objectives

Overall, existing methods for analyzing architectural drawing each have their strengths and weaknesses. The visual communication approach emphasizes the clarity of information delivery but pays less attention to the artistic value of drawings. Iconological analysis helps interpret the symbolic meanings in architectural drawing, but its analytical framework may not fully accommodate the unique characteristics of architectural drawing [

38,

39]. In response to the limitations of iconological analysis, recent studies in modern art have gradually shifted toward semiotic analysis [

40]. Since architectural drawing not only serves as a tool for conveying information but also involves spatial imagination and design expression, traditional iconological methods may struggle to fully decode its visual language. Therefore, the exploration of symbolic meaning within semiotics provides a more flexible analytical approach, allowing for a comprehensive examination of both the functional and artistic aspects of architectural drawing. This study attempts to integrate traditional iconological methods while drawing from semiotic approaches to symbolism, aiming to establish a new analytical perspective for evaluating the artistic and functional dimensions of architectural drawing.

3. Research Methods

First, this study selects four representative architectural architects as case study subjects. Through an in-depth analysis of several representative works by each artist, this study explores their drawing styles, technical applications, and the expression of functionality and artistic value in architectural drawing. The case study aims to summarize the drawing styles of architects, identify their main techniques, and further analyze the role of these drawings in architectural design representation, exploring their capacity for information delivery and expressive characteristics. At the same time, interview data are used to obtain their personal experiences, thought processes, and understanding of the functionality and artistic value of architectural drawing. The collected materials provide insights into how they perceive the role of architectural drawing in their work and how they balance information delivery and visual expressiveness in their drawings. These textual data, combined with the analysis of their works, support the in-depth interpretation of the case studies and enrich the understanding of the motivations and concepts behind architectural drawing creation.

In addition, to further reveal the visual language and semiotic characteristics of architectural drawing, this study integrates iconological analysis, symbolism analysis, and cartographic methods to construct a four-dimensional analytical framework (

Table 1), aiming to comprehensively evaluate both the functional and artistic aspects of architectural drawing:

Formal Analysis—The pre-iconographic description from iconology is combined with the icon analysis from semiology to identify architectural elements, spatial composition, and material textures in drawings, revealing how they convey architectural concepts as “iconic signs” based on similarity.

Cultural Analysis—Utilizing iconographic interpretation, combined with the architectural cultural context, this dimension explores how architectural symbols reference architectural functions, historical contexts, and social roles. By incorporating indexical sign analysis, it examines how the spatial atmosphere and human activities serve as indexical cues for architectural meaning, making architectural drawings not only visual representations but also carriers of cultural narratives.

Narrative and Symbolism Analysis—Drawing from visual culture studies [

41] is dimension investigates how architectural drawings employ spatial organization, color, and lighting to construct visual storytelling. Additionally, it examines how architectural drawings utilize symbolic signs to express specific values and historical memories, making them interpretable and symbolically meaningful within different cultural systems.

Social and Cultural Context Analysis—This dimension introduces a semiotic pragmatic perspective to investigate the multiple interpretations and re-codings of architectural drawings in different cultural settings. Building upon cartographic and urban spatial studies, and referencing

Art, Map and Cities [

42], it considers architectural drawings as a form of “visual mapping”, analyzing how they construct meaning within the interactions of globalization, modernization, and localization.

The integrated analytical framework not only reveals the visual language of architectural drawing but also analyzes its complex meanings in various cultural and social contexts.

This study primarily relies on collections of works and interview data, which may lead to the following biases and limitations: (1) Limited data sources: Interview data are subjective and may emphasize architects’ personal interpretations while neglecting the polysemous interpretations of audiences. Additionally, the limited number of sampled works may fail to cover the diversity and universality of architectural drawing. (2) Methodological bias: the small sample size in case studies limits the generalizability of the findings, and semiotic analysis may be influenced by cultural background misinterpretation. (3) Interpretative bias: this study tends to focus on architects’ creative intentions while overlooking the social contexts and the multiplicity of audience interpretations.

4. Case Study

4.1. Tomoyuki Tanaka

Tomoyuki Tanaka is a renowned Japanese architect and architectural illustrator who has been engaged in architectural drawing and education for many years. His works primarily feature blue ballpoint pen line drawings, known as “tanaper” (Tanaka’s pasu, with “pasu” being a Japanese abbreviation of the English word “perspective”). This distinctive drawing technique was developed by Tanaka in the late 1990s for architectural competitions and project bids. These works not only depict the spatial composition and overall form of buildings but also achieve a high level of “visual transparency” through the layering of multiple elements such as building functions, pedestrian flows, and transportation networks [

9]. In these layered images, viewers can simultaneously interpret the spatial structure, usage patterns, and operational logic of the city.

This study analyzes four deconstructive architectural drawings by Tomoyuki Tanaka depicting Japanese railway stations (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). These four works use monochromatic fine lines to outline the spatial layout and transportation flow of the stations, highlighting their order and complexity as urban hubs. The use of a bird’s-eye perspective avoids the visual compression caused by vanishing points, allowing the entire station scene to be evenly presented and enhancing spatial continuity. The stations are surrounded by dense urban buildings, reflecting Japan’s high level of urbanization, particularly the typical spatial layout of the Tokyo area. To emphasize the station itself and its transportation system, Tanaka deliberately minimized the depiction of surrounding buildings, using only a few lines to indicate their form, thus reducing unnecessary visual distractions and ensuring that viewers can directly focus on the composition of the transportation network. This “information selectivity” not only improves the readability of the image but also enhances its value as an architectural analytical tool.

In terms of dynamic representation, Tanaka’s works use variations in the density of dots and lines to depict pedestrian flow. Although these figures are represented by tiny dot-like elements or branching lines, their rhythmic arrangement and continuity allow viewers to clearly understand the circulation within the station. Tanaka’s drawing approach breaks away from traditional architectural drafting methods by integrating multiple layers of space into a single-perspective drawing, rather than using axonometric projections to separate and arrange different floors. This method not only preserves the overall sense of space but also creates an immersive experience for viewers, as if they are physically present in the bustling station, attempting to identify floors, routes, and the complexity of the urban transportation system.

Each of the four works exhibits distinct compositional features. For example, the drawing of Shinjuku Station uses large areas of blank space (

Figure 1b), allowing the railway tracks to extend from the station into the distance, symbolizing the “spatial freedom” brought by technological development. In contrast, the drawings of Shibuya Station (

Figure 2) and Tokyo Station (

Figure 1a) emphasize the visual effect of traversing the city, enhancing the urban narrative. In terms of composition, Shinjuku Station and Shibuya Station adopt diagonal perspectives, providing viewers with a convenient angle to comprehend the structure of the entire station. Tokyo Station, due to its historical significance and cultural symbolism, employs a strict symmetrical composition with a clear entrance guiding the viewer’s line of sight, reflecting its weighty presence and order as a central railway hub in Japan.

In terms of creative concept, Tanaka drew inspiration from the structural logic of the Chinese characters “well”, “valley”, and “field”. In his creative notes, he also referenced Jackson Pollock, Arata Isozaki, and Piet Mondrian [

10]. The influence of these artists is evident in Tanaka’s compositional arrangements, variations in line thickness, and layered information, making his works not only representations of architectural space but also reflections on modern urban development and architectural art movements. This provides viewers with an art background with richer interpretative possibilities.

Notably, Tanaka created two versions of the Shibuya Station drawings, corresponding to 1963 (

Figure 2a) and 2011 (

Figure 2b). Through the comparison of surrounding building forms, utility poles, pedestrian railings, and other details, viewers can intuitively perceive the traces of urban transformation over the past fifty years. Particularly, changes in building density, modernization of infrastructure, and alterations in pedestrian spaces reflect the accelerated urbanization and expansion of the railway system in Japan during this period. This is not merely a depiction of space but a symbolic record of urban history, demonstrating how architectural drawings serve as visual archives that document spatial evolution and societal changes in urban development.

In addition to his drawing creations, Tanaka systematically summarized the methodology of architectural drawing in his teaching publications [

11]. He emphasized the importance of clarifying the core message to be conveyed before drawing and exploring multiple compositional approaches to ensure clear communication of information. He advocated for the appropriate inclusion of background elements to convey a sense of spatial scale and usage, while also establishing a hierarchy of information during the drawing process to avoid excessive detailing that could undermine the overall effect. At the technical level, he preferred using bold lines to emphasize key elements and minimize the use of color to prevent visual distractions from the main content. Furthermore, he paid close attention to the adjustment of perspective points and the collage of elements, enhancing the atmosphere and immersive experience and allowing viewers to perceive the characteristics and spatial context of architectural works more intuitively.

4.2. Yusuke Koshima

Yusuke Koshima, a renowned Japanese architect, focused his doctoral dissertation on “critical creation through post-construction architectural drawings”. He has been engaged in architectural drawing and related theoretical explorations for many years, publishing multiple works on architectural drawing and architectural concepts [

12]. His works predominantly feature hand-drawn black line illustrations, utilizing collage techniques to integrate various perspectives, viewing distances, and content within a single drawing, aiming to maximize the presentation of information and details in architectural proposals. This study selects Koshima’s 2007 [

13] architectural drawing scroll

Connected Borders and two post-construction architectural drawings of his residential designs for analysis (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Connected Borders (

Figure 3) is a collage created by Yusuke Koshima after returning to Japan from his architectural study tour in Europe, reflecting his deep contemplation on what he observed and the future of architecture [

13]. The entire scroll is based on a single straight horizon line, primarily using an elevation view while flexibly adjusting angles and distances according to architectural styles and viewing needs, resulting in a dual effect that intertwines a flat map and a three-dimensional perspective. The initial part of the scroll (

Figure 3a) features mostly real-world buildings, which are overlaid within the same frame regardless of objective scale, presenting an “impossible urban landscape” that visually symbolizes the exchange and integration of urban cultures in the context of globalization. The building outlines remain delicate rather than bold, enhancing the “seamless connection” of the visual experience.

As the scroll progresses, architectural forms gradually break free from the constraints of materials, construction, and gravity, exhibiting a sense of freedom in height and volume (

Figure 3b). This symbolizes architecture as a vessel for culture, history, and imagination, transcending the boundaries of vision, culture, and reality within the drawing. This “timeless” spatial folding effect is not only a formal technique but also a conceptual approach that intertwines different temporalities within a single composition. Some elements retain traces of historical architecture, while others embody speculative future designs, creating a layered architectural narrative that exists beyond conventional time constraints. This characteristic is also reflected in his post-construction architectural drawings, where different eras and architectural styles coexist in a single visual field. The works alternate between interior and exterior architectural elements, constructing a narrative that spans time and style. Koshima employs meticulous line drawings to depict material contrasts, such as traditional Japanese roof tiles, wood grain, and stone blocks, using variations in line density to allow viewers to visually perceive the texture of materials and evoke discussions on locality and universality (

Figure 4a). This juxtaposition of historical references, contemporary forms, and speculative structures positions architectural drawing as a medium that connects past memories, present realities, and future imaginaries. These details also provide viewers with a path to imagine tactile sensations, enhancing the sense of presence in the drawings.

Koshima’s drawings adopt a fragmented perspective, using the collage of architectural elements to break traditional rules of perspective, presenting a nonlinear and decentralized spatial narrative that resonates with the fragmented perception of architecture experienced by users in real life, where a complete view of a building is rarely systematically perceived. In

Gunsoan Drawing (

Figure 4b), Koshima integrates abstract geometry with architectural language, where a solid blue square disrupts the continuity of architectural details, creating a sharp contrast with the surrounding intricate architectural elements. This design not only challenges viewers’ visual habits but also prompts reflection on the relationship between architectural functionality, reality, and imagination, blurring the boundaries between architecture and other art forms.

In interviews, Koshima emphasized that “yohaku” (blank space) is essential in architectural drawing creation [

13]. For example, in the

Connected Borders scroll, the blank area below the horizon line or the defined boundaries around the architectural drawings represent the “absence” set by the architect, while the “presence” that architectural drawings convey is highlighted through this contrast. He stressed that architecture can only enrich its expression to the fullest extent within specific defined boundaries. Koshima’s drawing language is not merely a product of hand–eye coordination but also a combination of tactile sensations, hand movements, public discourse, and self-dialogue, attempting to convey these elements that go beyond traditional architectural expression and presenting a diversified approach to architectural drawing [

15].

4.3. Yushan

Zeng Renzhen, an architect who works under the pseudonym “Yushan”, specializes in the painting and study of Chinese gardens, creating numerous research-based drawings that explore the relationships between Chinese gardens, landscapes, spaces, and people. His works primarily emulate traditional Chinese ink paintings and gongbi (meticulous brushwork) paintings, employing a limited number of scenes and architectural elements in diverse combinations to evoke the atmosphere of Chinese garden vignettes. This analysis selects four architectural drawings from his

Red and

Fantasy series [

16].

In the

Fantasy series (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6a), Yushan uses concise lines and a limited color palette (red, green, and blue) to depict architecture inspired by traditional Chinese gardens. By employing an axonometric-like perspective, he avoids spatial compression between near and far, enhancing the sense of spatial hierarchy and alluding to the “scenery-shifting” visual effect of Chinese gardens. Elements such as flying eaves, green tiles, and white walls highlight the characteristics of traditional Chinese architecture. The courtyard layout and winding paths symbolize the spatial organization of “separation without isolation”, while a defined entrance appears to invite viewers into the garden. However, the interior scenes of the architecture are mostly obscured by walls, leaving viewers to imagine the internal space through glimpses of figures or plants seen through wall openings or windows, reinforcing the artist’s intent to navigate between reality and imagination. The red rocks and blue vegetation, which are not naturalistic color representations, create a striking contrast that emphasizes the boundary between architecture and nature. Figures dressed in plain garments not only indicate the scale of the space but also symbolize ordinary individuals, highlighting the everyday life and livability of the place.

In

Fantasy 167 (

Figure 5a), the undulating roofline evokes the imagery of water, while the white-washed walls resemble clouds, further suggesting mountains and forming an abstract representation of natural landscapes. The layered composition and well-placed “liubai” (blank space) guide the viewer’s gaze through the architectural clusters, creating a dynamic “garden strolling” experience. In

Fantasy 136 (

Figure 5b), the vertical stacking of various architectural forms implies the cultural imagery of “ascending to gain a distant view”, symbolizing the extension of time and space, as well as architecture’s narrative role as a cultural vessel. Although

Fantasy 015 (

Figure 6a) lacks a visible water surface, a small boat sailing toward the architecture subtly indicates the presence of water. The contrast between the curvilinear mountain forms and the straight architectural lines expresses the coexistence of nature and human-made structures, while the density and layering of lines symbolize the infinite expanse of space and time.

In the

Red series (

Figure 6b), Yushan shifts to a block-based painting approach, where red represents both the red soil seen in the

Fantasy series and the traditional red bricks used in Chinese architecture, reflecting a strong regional identity. The gentle contrast between red and blue creates a harmonious blend of architecture and nature. The arched doorways, as culturally symbolic elements in architectural history, point to the exchange and integration of Eastern and Western architectural forms. The interaction between cranes, swallows, and human figures in the paintings adds a sense of leisure to space. The curved ends of columns, resembling unfinished window openings, frame human activities along with the layered architectural forms in the background, emphasizing spatial permeability and continuity while also highlighting separation and boundaries.

These works may evoke multiple interpretations across different cultural contexts: Chinese audiences might view them as an homage to and representation of traditional gardens and lifestyles, while also reflecting on modern architectural concepts; Western audiences, on the other hand, might interpret them as a symbolic abstraction of Eastern spatial concepts and modern architectural language, further reinforced using traditional painting techniques. Furthermore, these works not only depict spatial compositions but also integrate temporal elements that reflect the historical evolution of architecture and gardens. While Yushan’s drawings do not explicitly indicate specific time periods, the architectural forms, landscape arrangements, and symbolic use of color subtly reference different stages of garden culture, allowing viewers to perceive both the weight of history and its connection to contemporary architectural discourse. This multiplicity of interpretations exemplifies the artistic nature of architectural drawings within diverse cultural and social contexts.

In Yushan’s collection of works, he mentions that these small-scale architectural drawings initially served merely as a means of conceptual training for garden design [

17]. However, during the creative process, he actively drew inspiration from real garden experiences and traditional Chinese paintings. Although these drawings lack the detail and precision of architectural renderings, they possess unique value in expressing architectural intentions. Most notably, he emphasizes the concept of “embodying the painting” [

18], where figures in the drawings, as spatial participants, convey realistic life and interactions within architectural settings through their postures and activities, endowing the space with vivid sensory perception. The concept of borrowing from nature’s craftsmanship), frequently referenced throughout his creative career, advocates for the harmonious coexistence of nature and human-made architecture through thoughtful craftsmanship and refinement. This philosophy is particularly evident in his works, where mountains integrated into architectural spaces symbolize the direct manifestation of the coexistence between nature’s craftsmanship and human craftsmanship.

4.4. Drawing Architecture Studio (DAS)

Drawing Architecture Studio (DAS), co-founded by Li Han and Hu Yan in Beijing in 2013, is dedicated to architectural drawing, architectural design, and urban research practice. DAS explores the possibilities of drawing, space, and urban research in a distinctive way, using architectural drafting software as a tool and drawing inspiration from architecture, art, popular culture, and everyday life to create grand and complex urban landscape images [

19]. At the same time, DAS regards infinitely scalable vector images as architectural materials, exploring multiple paths for virtual images to return to the material world, thereby breaking the boundary between images and space.

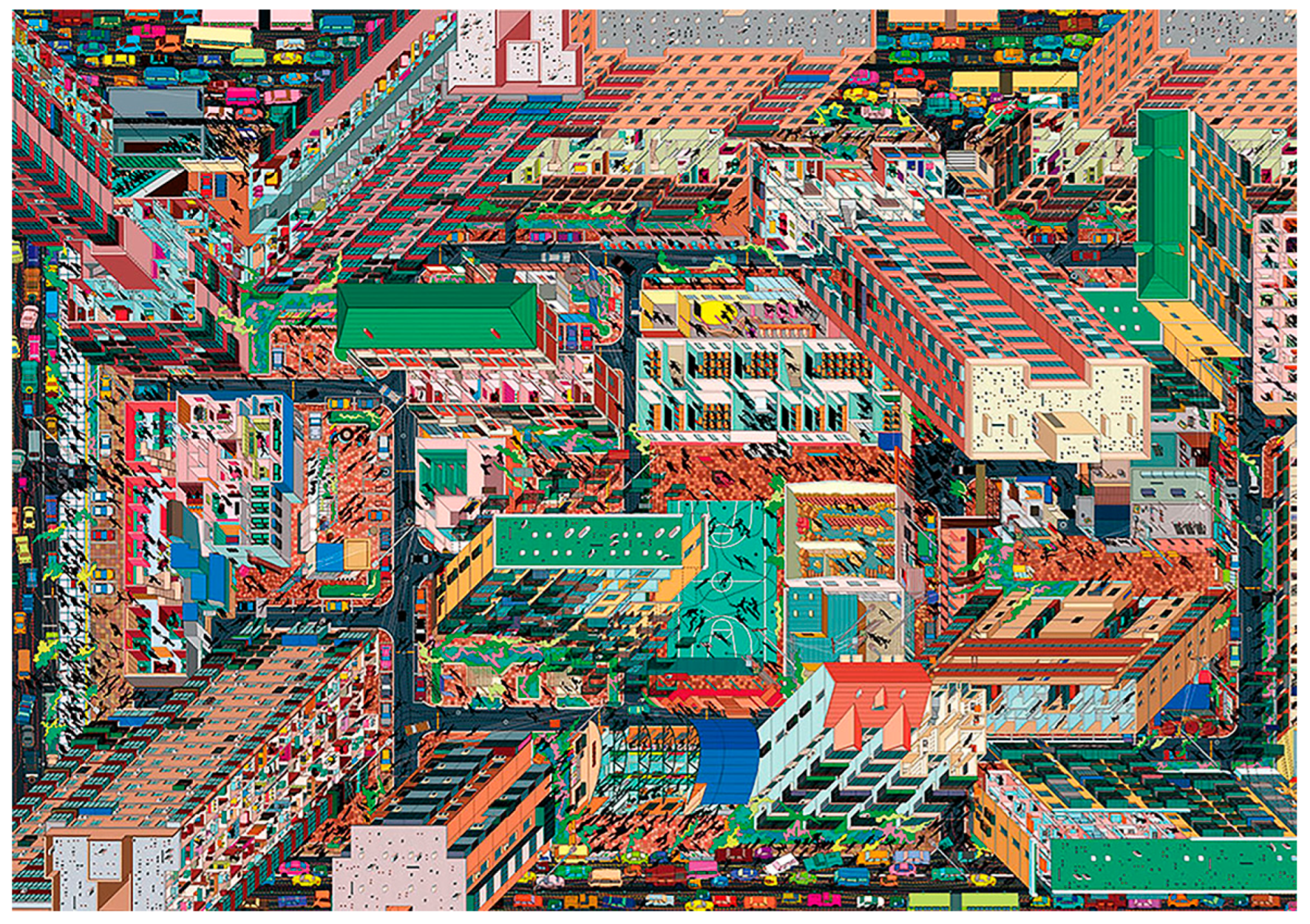

The architectural drawings of Drawing Architecture Studio adopt a complex axonometric method, avoiding the visual compression caused by perspective vanishing points, ensuring that buildings and spaces are evenly distributed across the image, thus breaking the limitations of traditional viewpoints (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). This drawing approach not only provides a highly detailed reproduction of urban spaces but also allows viewers, through an omniscient perspective beyond real-world photography, to re-examine the complexity of urban environments [

20,

22]. The images are filled with intricate details: rooftops, walls, trees, interior and exterior spaces, and various human activities are all precisely depicted. The dynamic movements of the figures serve not only as part of the visual narrative but also as index symbols, indicating high pedestrian flow and social interaction within the neighborhood. This synchronic spatial expression enables the drawings to surpass traditional architectural representation methods by distancing human sensibility, allowing viewers to receive the conveyed information rationally and then find a projection of their own lived experiences within the everyday scenes depicted, fostering a deeper resonance.

In the

Sanlitun Series (

Figure 7a), Drawing Architecture Studio adopts an open composition, using sectional views to reveal interior architectural activities. The exposed rooftops not only enhance spatial readability but also, through exposed beams, continuous furniture arrangements and trees that traverse the image and visually connect different scenes, conveying the repetitiveness and rhythm of urban life. In

Under The Zhengyangmen Series (

Figure 7b), the juxtaposition of classical and modern architecture creates a temporal tension that contrasts historical periods. The tilted perspective intensifies the sense of urban transformation over time while emphasizing spatial instability. This staggered architectural form and dynamic viewpoint reinforce the sense of urban hybridity and disorder, making the image not only a record of architecture but also a reflection of social and cultural phenomena.

In

Tuanjiehu (

Figure 8), a blue basketball court serves as the visual center, functioning as both an actual community space and a symbol of publicity and social needs in urban life. The architectural layout and street scenes point to the typical work-unit courtyards and community forms found in Chinese cities, illustrating the realities of high population density and limited spatial resources in major metropolises. The dense architectural arrangement, narrow streets, and overlapping apartment blocks bring a sense of order while simultaneously creating visual pressure, prompting viewers to reflect on the pace of modern urban life, social complexity, and interpersonal relationships in collective living.

The works of Drawing Architecture Studio are not merely direct depictions of urban landscapes but also reinterpretations of contemporary urban phenomena. By employing an axonometric perspective, they eliminate the visual limitations of traditional perspective methods, allowing architecture and the city to unfold on the same plane, thereby enhancing the readability of urban spaces. At the same time, the established symbolic system within their works—from the use of highly saturated colors to the indexing of human activities—reveals the multifaceted relationship between architecture and society. Furthermore, these works exhibit a synchronic spatial narrative, juxtaposing different scenes and activities within a single composition, allowing viewers to interpret the multi-dimensional operations of the city through a nonlinear spatial logic. This approach not only highlights the dynamic nature of urban life but also creates an architectural representation that transcends temporal linearity, transforming the image into a condensed portrayal of metropolitan existence rather than a static record of a single moment. For audiences from different cultural backgrounds, these works serve not only as precise records of contemporary Chinese urban realities but also as a universal reflection on modern urban culture.

Li Han, co-founder of Drawing Architecture Studio, stated in an interview that drawing, as an essential skill for architects, should continuously expand its expressive boundaries [

21]. In an era when photography gradually replaced the realistic function of drawing, axonometric drawings based on mathematical models have become a unique visual language that photography cannot substitute. By combining digital models with hand-drawn colors and background elements, DAS’s works not only transcend traditional architectural blueprints but also serve as a popular cultural medium accessible to the general public. DAS adopts a highly realistic approach inspired by Atelier Bow-Wow’s

Made in Tokyo, reducing the cognitive barrier for the public and making complex architectural and urban research more perceptible and readable. Li Han emphasized that the initial intention of their work is to document the existing social landscape of old Beijing and to disseminate it as a cultural carrier to a broader audience. This strategy resonates with Atelier Bow-Wow’s concept of

Architectural Ethnography, which emphasizes that “life surpasses architecture”—architectural drawing is not merely a representation of built space but also a means of recording, analyzing, and discussing the complex relationships between people and their architectural environments [

43]. From this perspective, DAS’s drawings—with their rich urban life details, high information density, and spatial usage patterns—can be seen as a form of visual ethnography of contemporary cities.

5. Discussion

Tomoyuki Tanaka, Yusuke Koshima, Yushan, and Drawing Architecture Studio (DAS) each demonstrate distinct artistic languages and architectural thinking in their architectural drawing practices (

Table 2). Tanaka employs blue line drawings to depict the complex spatial structures and dynamic order of Japanese train stations, emphasizing functionality and spatial logic. Koshima integrates multiple perspectives through collage, breaking continuity and centrality, transforming architectural drawing into a medium for narrative and cultural reflection. Yushan extends the aesthetics of traditional Chinese gardens, highlighting spatial poetics and humanistic connotations, using simplified lines and highly conceptual colors to convey the ideas of “separation without isolation” and “scenery shifting with movement”. DAS utilizes digital drafting and highly saturated colors to present the intricate urban landscape of Beijing, emphasizing the role of architectural drawing in visual communication and social documentation.

The four architects exhibit distinct techniques in architectural drawing: Tanaka prioritizes precision through hand-drawn lines, Koshima employs collage to create multi-perspective narratives, Yushan utilizes traditional Chinese painting techniques to evoke atmosphere, and Drawing Architecture Studio leverages digital technology to craft hyper-realistic urban landscapes. Despite their differences, they share a commonality: none of them treat architectural drawing merely as a design tool but as a medium for artistic creation, cultural transmission, and social expression. Tanaka and Drawing Architecture Studio both pursue highly detailed presentations—one through monochrome line drawings, the other through vibrant colors and intricate elements; Koshima and Yushan focus more on cultural narratives—one folding history and future together, the other conveying profound cultural significance through minimal colors.

Cultural heritage is a shared focus among the four architects. Tanaka’s works reflect the order and modernity of Japanese urban culture, Koshima explores the exchange and continuity of architectural culture in the context of globalization, Yushan extends traditional Chinese spatial concepts and aesthetics through gardens and landscapes, and Drawing Architecture Studio meticulously depicts Beijing’s urban fabric, recording the social and cultural realities of contemporary Chinese cities. Their works achieve a balance between functionality and artistry: Tanaka integrates artistry into functional expression, Koshima embeds architectural thinking within narrative, Yushan interprets architectural space through artistic techniques, and Drawing Architecture Studio analyzes and documents urban functions through artistic digital drawings.

Furthermore, the inheritance of cultural traditions is also evident in the techniques of architectural drawing. While both Eastern and Western painting traditions attempt to depict three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, their approaches to perspective differ significantly. Western perspective techniques emphasize geometric perspective, relying on a single vanishing point to establish depth and spatial hierarchy. In contrast, the Eastern perspective tends to adopt multi-perspective composition, allowing the image to expand outward rather than converging toward a focal point. This characteristic is evident in the works of Yushan and Tanaka—the former utilizes an elevation projection to eliminate distant perspectives, while the latter employs axonometric views to counteract perspective distortion, ensuring that spatial relationships remain evenly distributed across the image.

Additionally, traditional Chinese paintings, such as Along the River During the Qingming Festival, and Japanese bird’s-eye view paintings, such as Famous Views of Edo, adopt a handscroll composition with multiple vanishing points, creating an open spatial layout that reduces focal contrast and instead unfolds the visual narrative through layered spatial elements. This influence is not only reflected in Koshima’s collage technique, where the deconstruction and reconstruction of multiple viewpoints align with the temporal and spatial continuity of handscroll paintings, but also in DAS’s large-scale architectural drawings, where, despite their digital medium, the organization of visual information bears similarities to traditional handscroll compositions. Furthermore, Japanese ukiyo-e prints frequently utilize triptych formats, wherein three connected images form a thematic unit. This structural approach is also present in Koshima’s long scrolls, where different sections of the composition function as interconnected yet distinct thematic segments.

In terms of color application, Yushan’s red and blue palette corresponds to the blue-green landscape painting and traditional gongbi painting of Chinese art, where symbolic color schemes enhance the cultural narrative embedded in the imagery. Meanwhile, Koshima’s emphasis on material texture and shadow gradation resonates with Japanese Wabi-sabi aesthetics and the philosophical reflections on light and materiality in Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows, reinforcing a focus on the temporality and material transformation of architecture.

This comparison demonstrates the multifaceted value of architectural drawing in contemporary architectural research. Semiotic analysis reveals the role of architectural drawing in the processes of globalization, modernization, and localization, offering a new research perspective that examines its multiple meanings in cultural heritage and social interaction. It affirms the autonomy and artistic nature of architectural drawing while addressing gaps in existing research. Semiotic methods not only broaden the scope of architectural drawing studies but also open new possibilities for their application in art theory.

6. Conclusions

This study, combining iconography, symbolic analysis, and cartographic methods, systematically analyzes the architectural drawings of Tomoyuki Tanaka, Yusuke Koshima, Yushan, and Drawing Architecture Studio (DAS), aiming to reveal the multiple meanings of architectural drawings in terms of visual representation, spatial thinking, cultural heritage, and viewer interpretation. This study finds that, despite differences in style, technique, and medium, the works of these four architects share commonalities in balancing functionality and artistry, expressing architecture as a cultural carrier, and demonstrating how architectural images transcend their drafting functions to become independent visual narratives. Architectural drawing is not only a means for architects to convey design intentions but also a unique visual language capable of carrying architectural concepts, cultural memory, and social reality, forming a visual archive with historical depth.

The architects demonstrated distinct artistic languages and architectural thinking in their architectural drawing practices. Tanaka employed blue line drawings to represent complex spaces and dynamic order, with hand-drawn details resembling BIM models, achieving a fusion of technicality and artistry, presenting a “poeticization of technical images” and a de-temporalized urban landscape. Koshima used collage to juxtapose different architectural styles and historical periods, breaking traditional perspectives and creating a nonlinear narrative that positions architecture as a convergence of history, memory, and future imagination. Yushan, centering on Chinese gardens, adopted traditional gongbi painting techniques and symbolic colors to create spatial experiences interwoven with reality and illusion. DAS utilized digital tools and high-precision axonometric methods to transform urban landscapes into informational images, generating a hyper-realistic urban vision that emphasizes the role of architecture within the city.

By integrating iconography, symbolic analysis, and cartographic methods, a four-dimensional analytical model is applied to reveal how the four architects establish connections between architectural information transmission, artistic expression, and cultural narrative. Tanaka, through highly precise linear expressions, reflects the order of modern urban infrastructure and explores the operational mechanisms of contemporary cities. Koshima’s collage compositions utilize cultural symbols to break static characteristics and create multi-dimensional narratives. Yushan employs symbolic elements, such as red rocks and blue plants, to convey the temporality and spatial fluidity of Chinese gardens. DAS, at the level of pragmatics in semiotics, generates a near-urban reality experience through high information density and visual overload, exploring the multiple interpretations of architectural images.

However, this study also has certain limitations. First, the number of research subjects is relatively limited. The four selected architects and their works are representative but primarily focus on specific types of contemporary Chinese and Japanese architectural drawing. However, architectural drawing practices extend far beyond these examples, and numerous other styles and methods, such as computer-generated architectural imagery and surrealist architectural drawing, remain unexplored and warrant further research. This study employs iconological analysis, symbolism analysis, and cartographic methods to examine the visual language, symbolic meanings, and cultural contexts of architectural drawings. Its scope primarily focuses on architectural drawing as a form of visual expression, cultural narrative, and symbolic system. However, this study’s methodology is not applicable to analyzing the technical construction, engineering realization, or architectural implementation of drawings. Future research could integrate architectural studies, design, and digital media research to expand the understanding of architectural drawing in broader disciplinary contexts. Additionally, this study focuses mainly on semiotic interpretation of the works and does not conduct empirical research on viewers’ actual perception and reception. Future studies could employ experimental methods such as audience interviews and eye-tracking to further explore the readability and information transmission mechanisms of architectural drawings.

In terms of practical application, this study provides new perspectives on the value of architectural drawing in fields such as architectural education, artistic creation, and urban studies. As an independent art form, architectural drawing can serve as a significant research subject in the interdisciplinary field of architecture and art, further promoting the experimental development of contemporary architectural imagery. In the field of urban studies, architectural drawing can be utilized in urban planning and historical research as an important tool for visually analyzing and culturally interpreting existing urban spaces. The practice of Drawing Architecture Studio has already demonstrated that architectural drawing is not merely a means of expression for architects but also a form of social and cultural documentation that can even influence public perceptions of urban space.

In conclusion, this study, through semiotic analysis, reveals the multifaceted value of architectural drawing as an intersection of art and architecture and explores its interpretation across different cultural contexts. Although the forms of architectural drawing continue to evolve, its core role in architectural practice, cultural narrative, and artistic creation remains indispensable. Future research will further explore how architectural drawing adapts to technological transformations while deepening its applications in interdisciplinary studies, promoting its continued development in the fields of architecture, art, and social sciences.