Improving Designs of Halbach Cylinder-Based Magnetic Assembly with High- and Low-Field Regions for a Rotating Magnetic Refrigerator

Abstract

1. Introduction

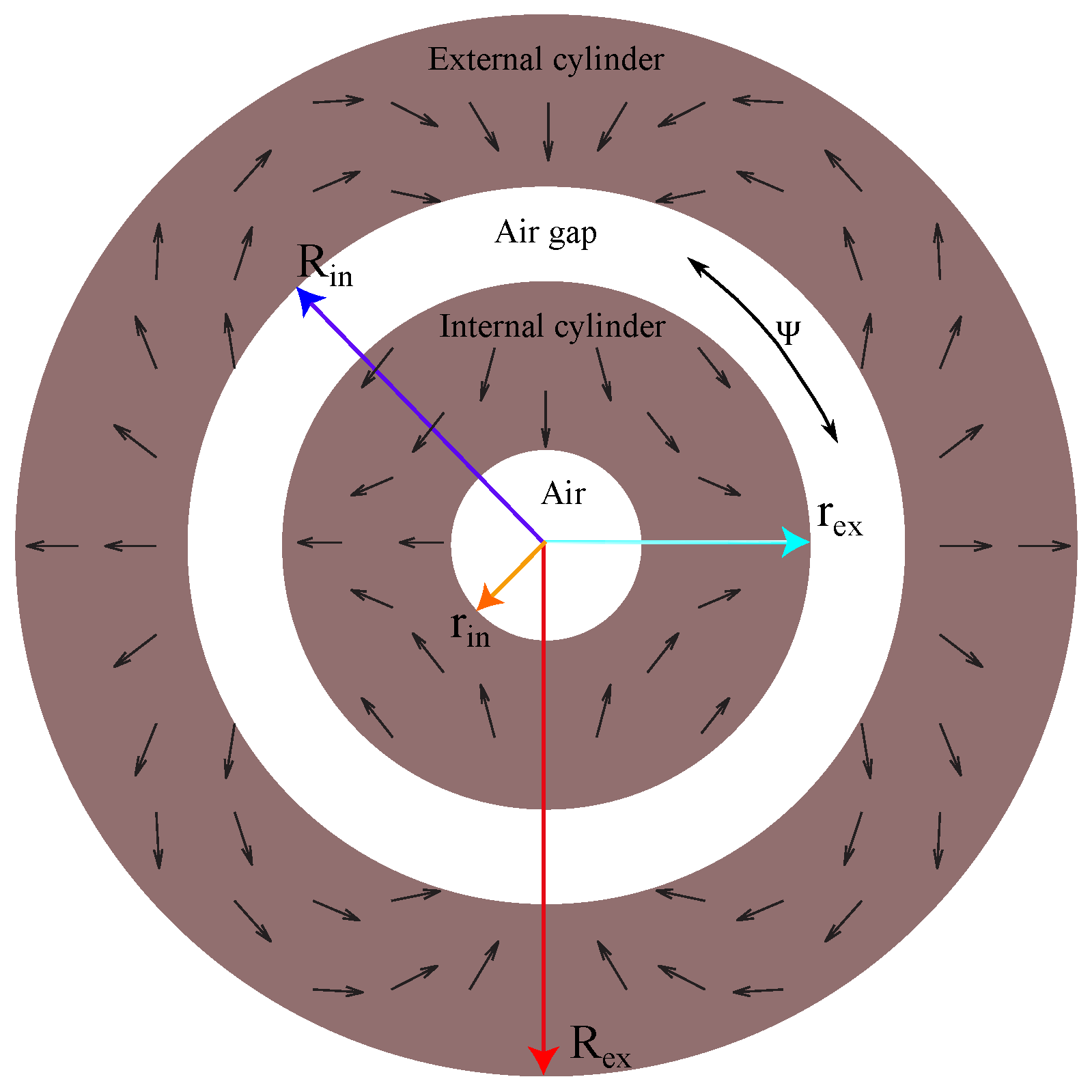

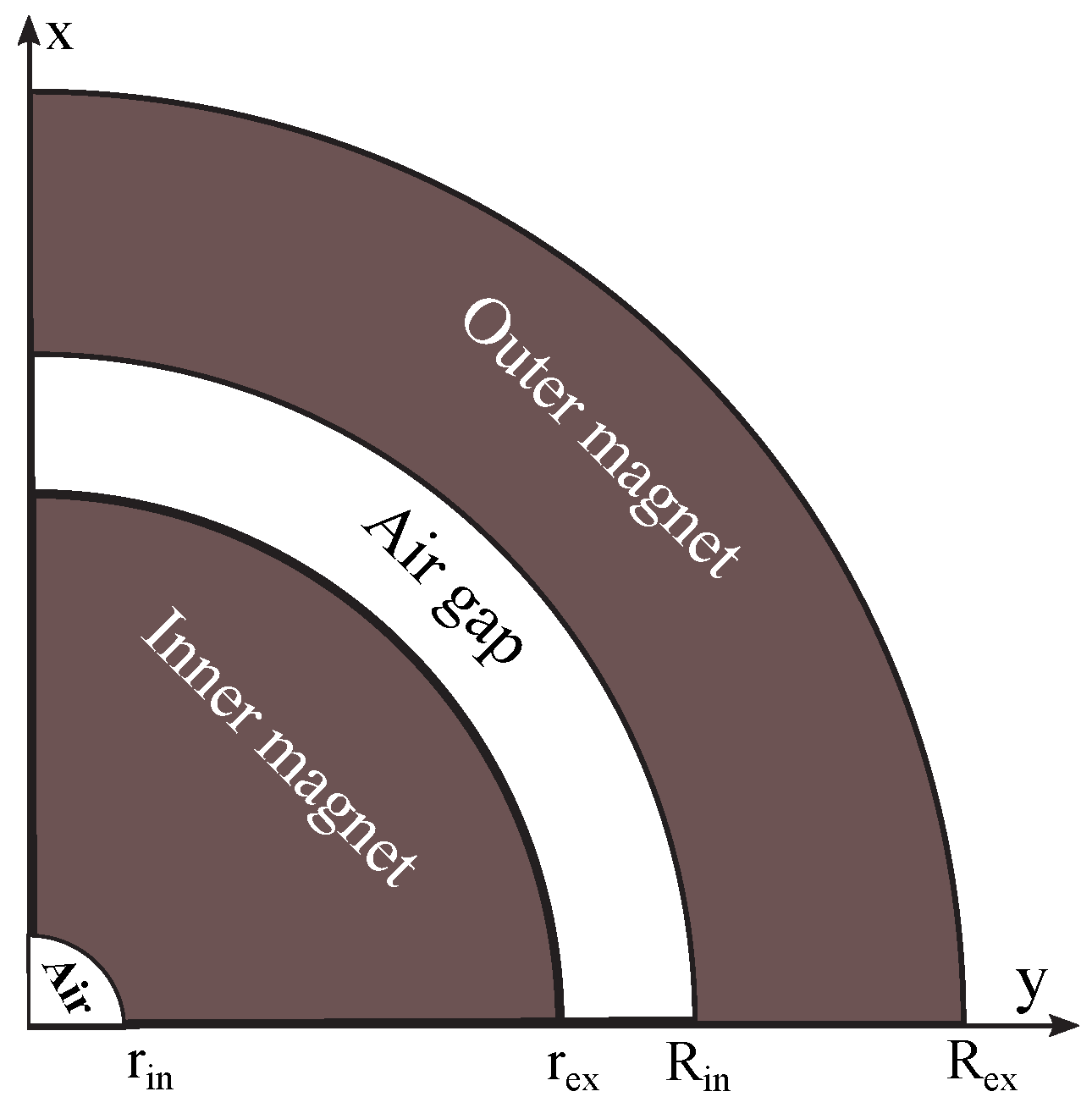

2. Prototype Design

3. Physical Model

4. Requirements on Magnet Design

- High magnetic flux density over two large regions

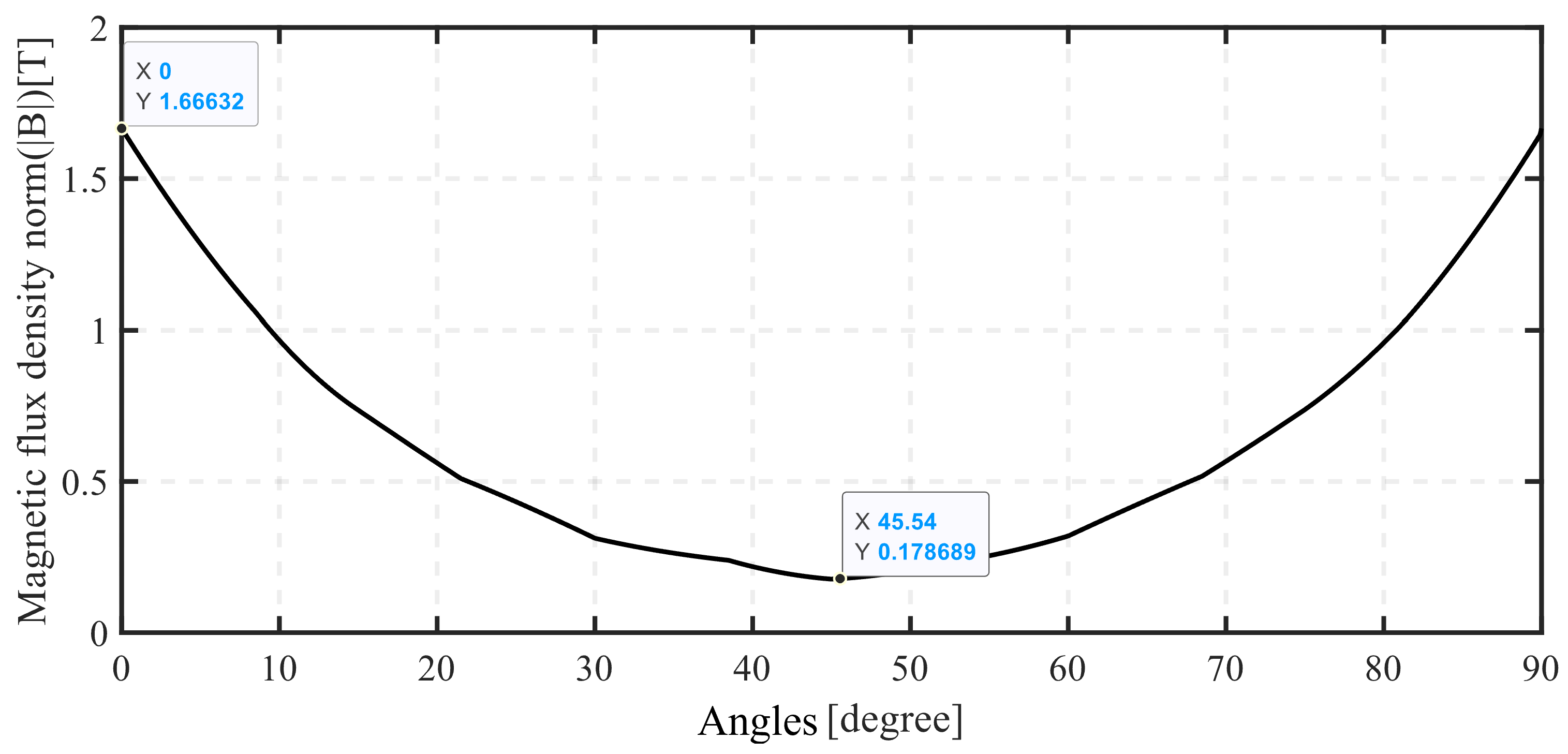

- Very low-magnetic-flux density over two large regions

- Homogeneous field distribution within two high- and two low-field regions

- Air-gap volume maximized ratio to the volume of the magnet

- Magnetocaloric material continuous use

- Replacement of some hard magnet components with another low-cost material

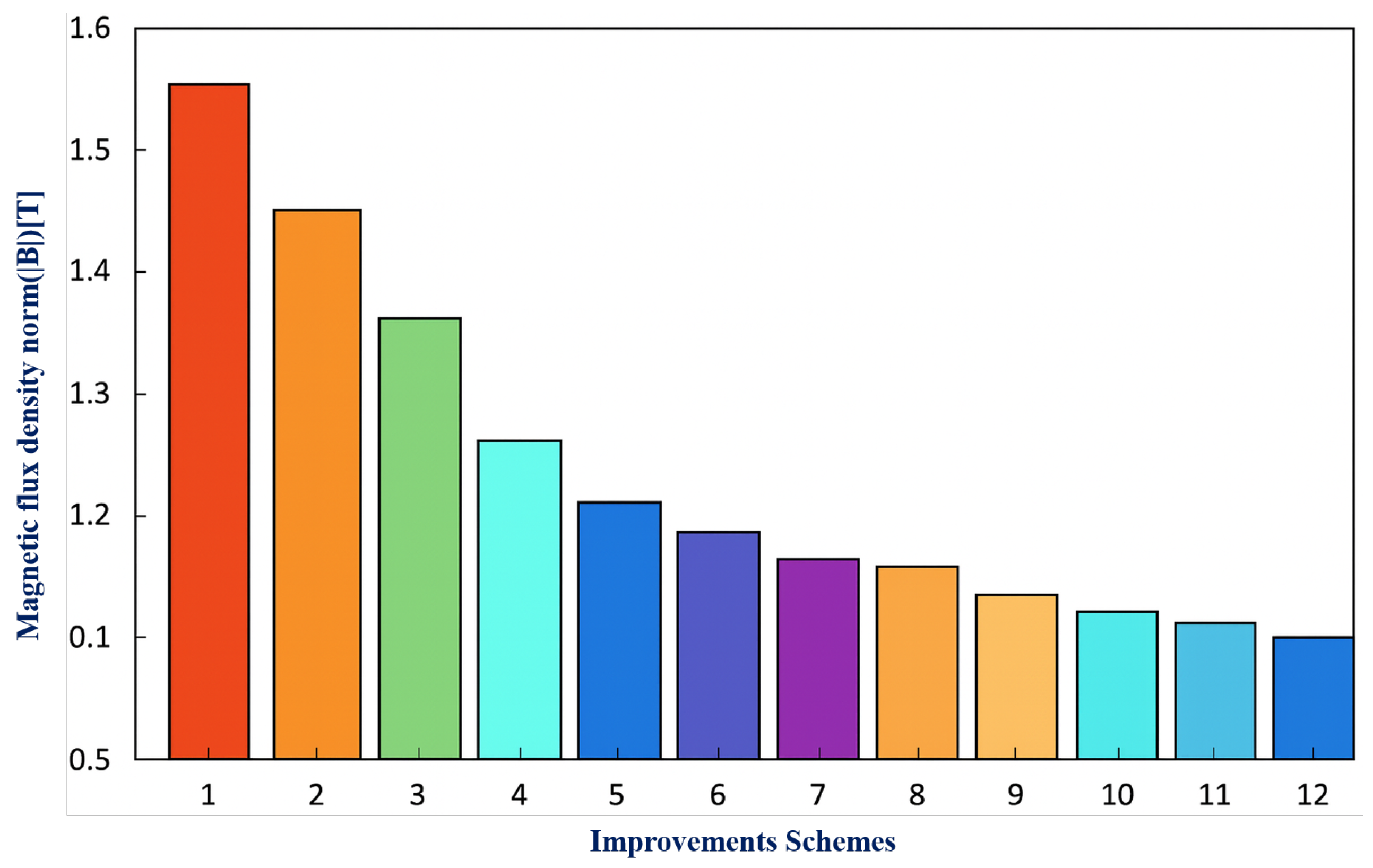

5. Optimization Procedure and Its Implementation

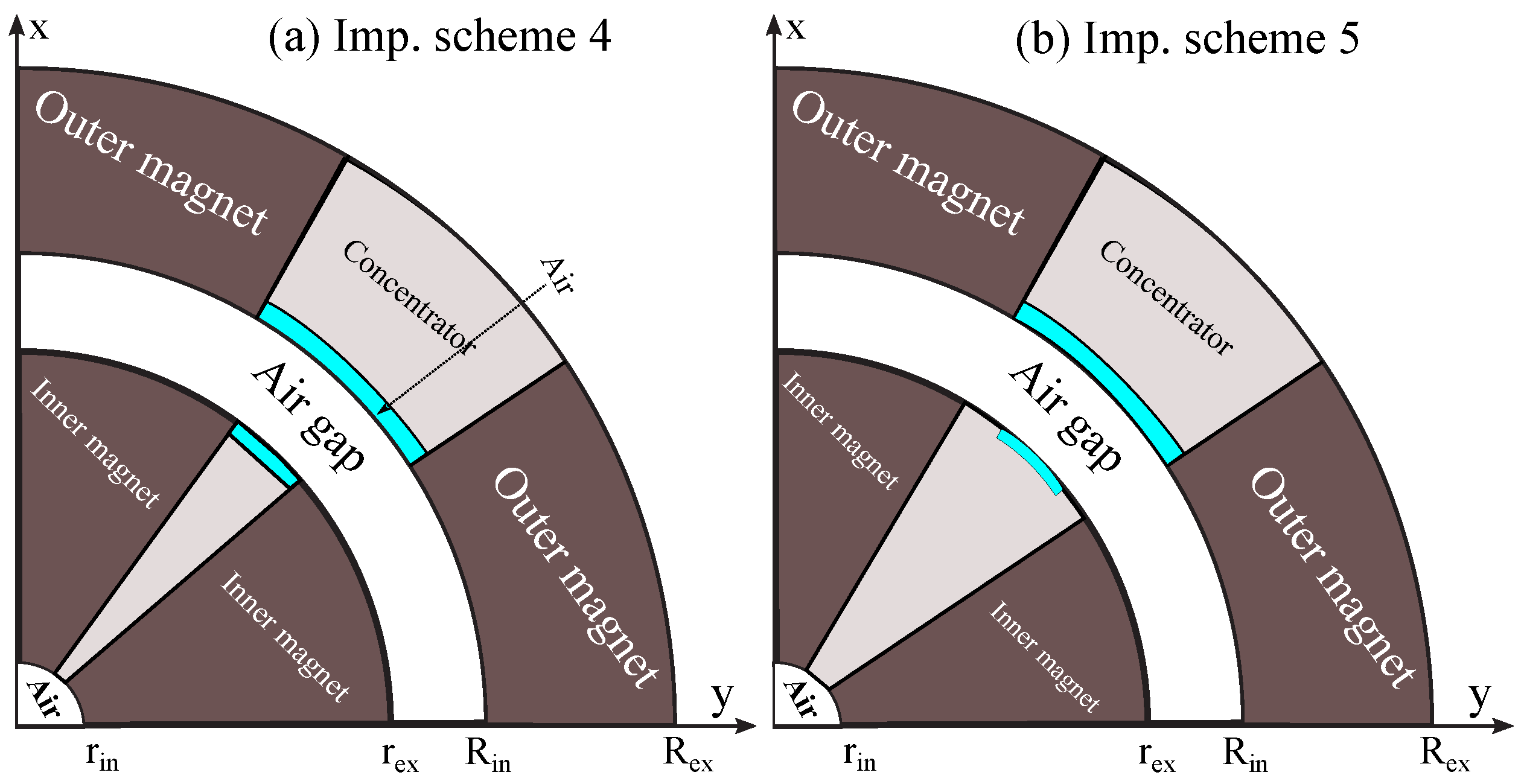

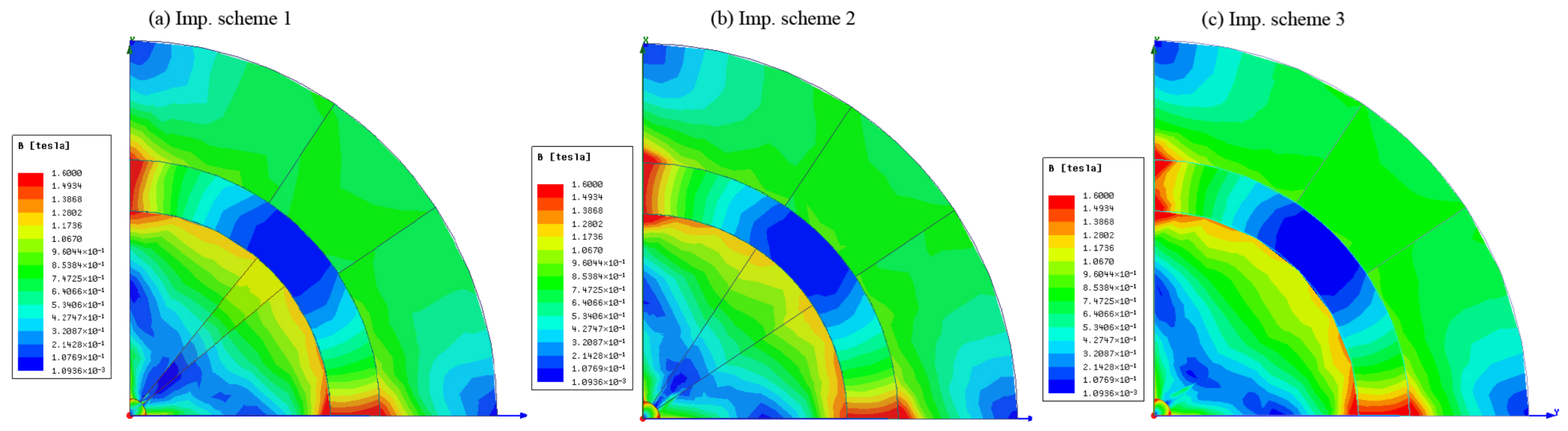

5.1. Concentration of Magnetic-Flux Density

5.2. Reduction of Magnetic-Flux Density in Low Regions

5.3. Augmentation of Magnetic-Flux Density in High Regions with Concentration of the Magnetic-Flux Density

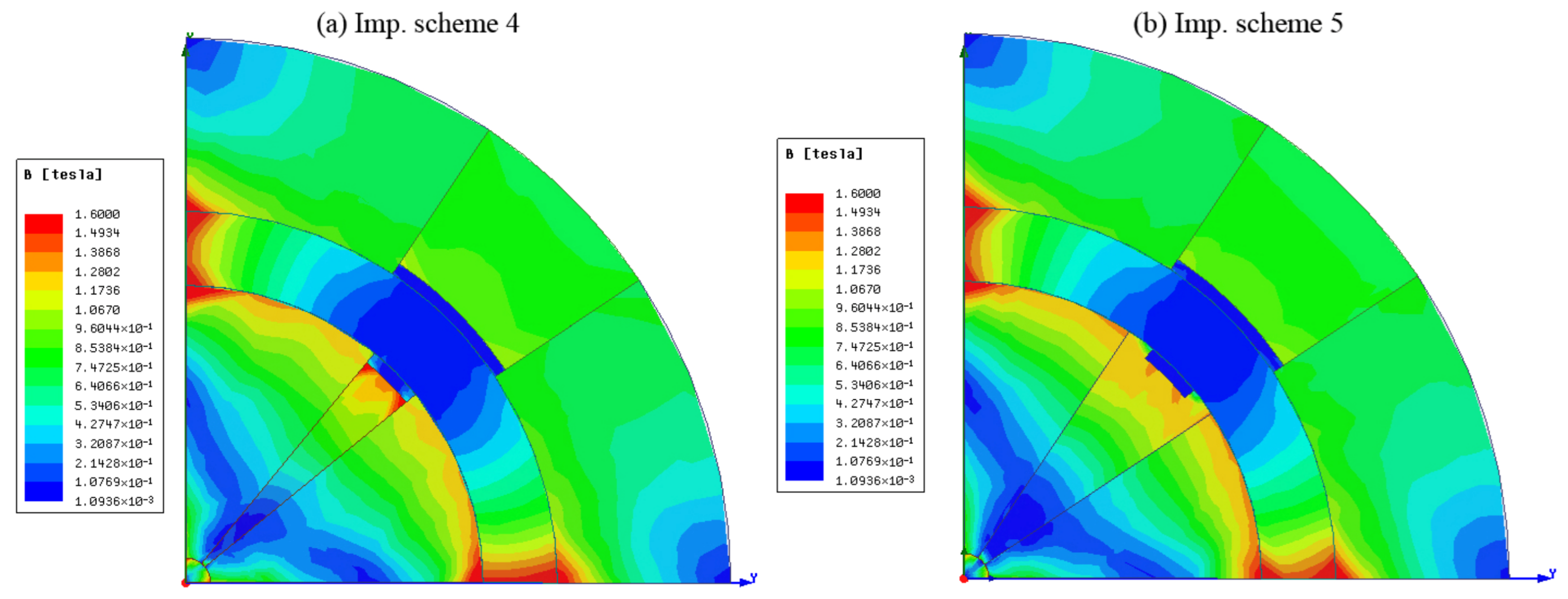

5.4. Optimization of Magnet Material with Reduction of the Magnetic-Flux Density in Low Regions and Augmentation of Magnetic-Flux Density in High Regions

5.5. Optimization of Magnet Operating Point by Including Another Low-Cost Material and Reduction of Leakage Flux

6. Simulation Procedure

- Nature of the permanent magnet: The device uses Neodymium–Iron–Boron (FeNdB) permanent magnets, grade N52, due to their high remanence and energy product.

- Temperature dependence: The remanent flux density of FeNdB magnets decreases linearly with temperature, approximately −0.11% per °C, consistent with data from Kresse et al. [36].

- Temperature-related risk: FeNdB magnets may experience reversible demagnetization when the combined temperature and external field exceed the intrinsic coercivity, which was checked to remain within the safe operating range in all simulated cases.

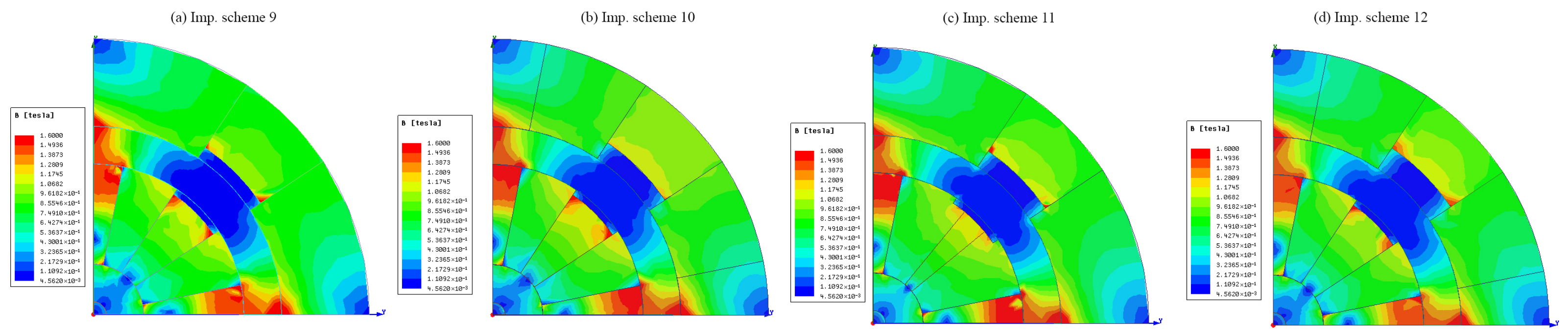

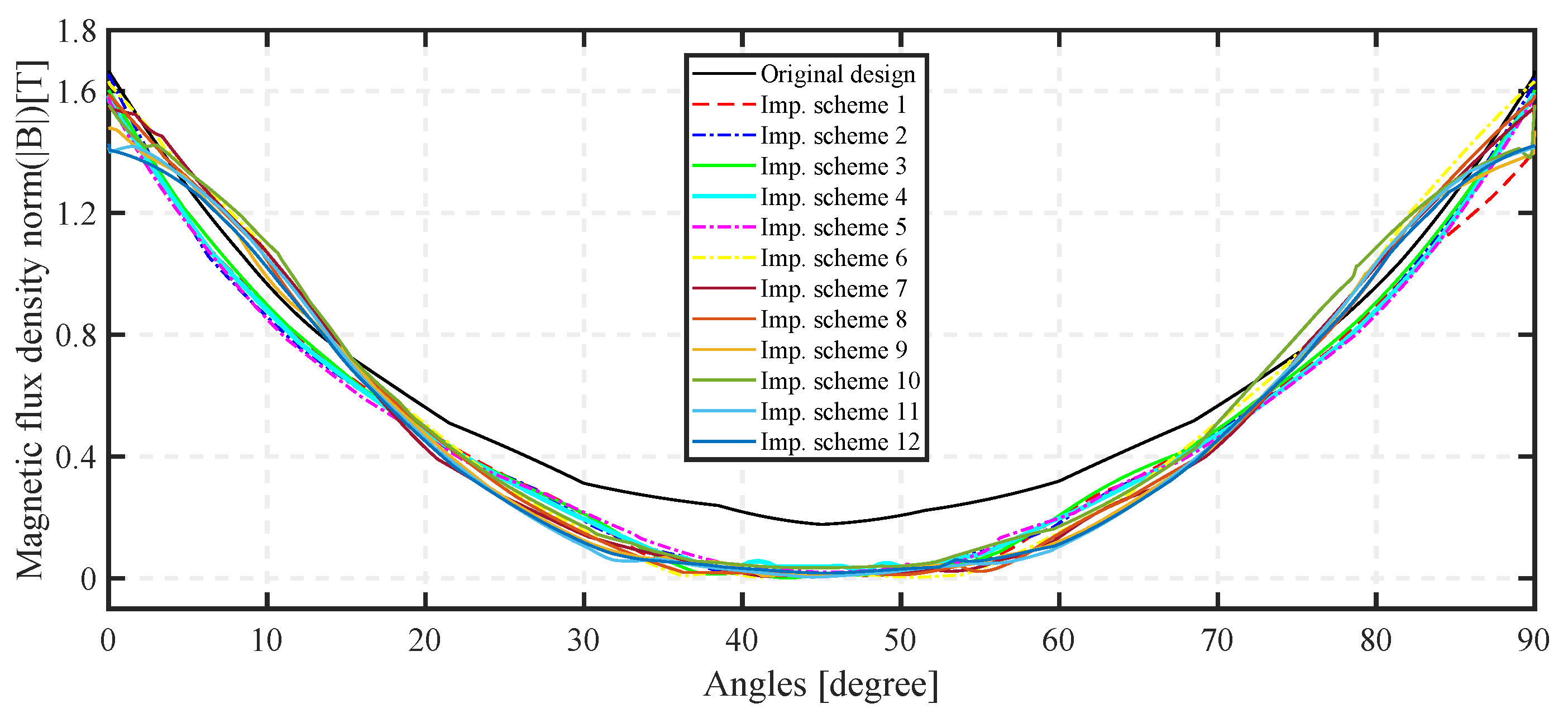

7. Simulation Results and Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | |

| MF | Magnetic field |

| MFD | Magnetic-flux density |

| RMR | Rotary magnetic refrigeration |

| PMMR | Permanent-magnet magnetic refrigerator |

| FDR | Flux-density regions |

| FeNdB | Neodymium–Iron–Boron magnet |

| MCE | Magnetocaloric effect |

| MR | Magnetic refrigeration |

| AMR | Active magnetic regeneration |

| Symbols | |

| T | Temperature |

| Curie temperature | |

| Adiabatic temperature | |

| h | Integer wave number |

| Coercivity | |

| Internal radius of outer cylinder (m) | |

| External radius of outer cylinder (m) | |

| Internal radius of inner cylinder (m) | |

| External radius of inner cylinder (m) | |

| Remanent flux-density magnitude | |

| Radial component of the remanence | |

| Tangential component of the remanence | |

| Peripheral angle | |

| Conductivity | |

| Relative permeability | |

| Density |

References

- Bjørk, R.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Smith, A.; Christensen, D.V.; Pryds, N. An optimized magnet for magnetic refrigeration. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322, 3324–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørk, R.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Smith, A.; Pryds, N. Review and comparison of magnet designs for magnetic refrigeration. Int. J. Refrig. 2010, 33, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, D.; Engelbrecht, K.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Bjørk, R.; Nielsen, K.K.; Insinga, A.R.; Pryds, N. Design and experimental tests of a rotary active magnetic regenerator prototype. Int. J. Refrig. 2015, 58, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Liu, M.; Egolf, P.W.; Kitanovski, A. A review of magnetic refrigerator and heat pump prototypes built before the year 2010. Int. J. Refrig. 2010, 33, 1029–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanovski, A.; Egolf, P.W. Thermodynamics of magnetic refrigeration. Int. J. Refrig. 2006, 29, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitanovski, A.; Tušek, J.; Tomc, U.; Plaznik, U.; Ožbolt, M.; Poredoš, A. Magnetocaloric Energy Conversion: From Theory to Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pecharsky, V.K.; Gschneidner, K.A. Advanced magnetocaloric materials: What does the future hold? Int. J. Refrig. 2006, 29, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbrecht, K.; Eriksen, D.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Bjørk, R.; Geyti, J.; Lozano, J.A.; Nielsen, K.K.; Saxild, F.; Smith, A.; Pryds, N. Experimental results for a novel rotary active magnetic regenerator. Int. J. Refrig. 2012, 35, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyber, R.; Trevizoli, P.V.; Christiaanse, T.V.; Govindappa, P.; Niknia, I.; Rowe, A. Permanent magnet design for magnetic heat pumps using total cost minimization. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 442, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamir, A.; Semma, E.; Dabachi, M.A. Modeling and numerical simulation of soft ferromagnetic materials used in electrical machinery. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 30, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohigas, X.; Molins, E.; Roig, A.; Tejada, J.; Zhang, X.X. Room-temperature magnetic refrigerator using permanent magnets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2000, 36, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørk, R.; Smith, A.; Bahl, C.R.H. Analysis of the magnetic field, force, and torque for two-dimensional Halbach cylinders. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørk, R.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Smith, A.; Pryds, N. Comparison of adjustable permanent magnetic field sources. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2010, 322, 3664–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Li, X.; Xia, D. Design and experiment of a rotary room temperature permanent magnet refrigerator. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2010, 20, 870–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tušek, J.; Zupan, S.; Šarlah, A.; Prebil, I.; Poredoš, A. Development of a rotary magnetic refrigerator. Int. J. Refrig. 2010, 33, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, A.; Rowe, A. Permanent magnet magnetic refrigerator design and experimental characterization. Int. J. Refrig. 2011, 34, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørk, R.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Smith, A.; Pryds, N. Improving magnet designs with high and low field regions. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2011, 47, 1687–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, C.R.H.; Engelbrecht, K.; Bjørk, R.; Eriksen, D.; Smith, A.; Nielsen, K.K.; Pryds, N. Design concepts for a continuously rotating active magnetic regenerator. Int. J. Refrig. 2011, 34, 1792–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, S.; Yu, S.; Ji, H.; Luo, X. Numerical simulation and performance improvement of a multi-polar concentric Halbach cylindrical magnet for magnetic refrigeration. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2016, 405, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insinga, A.R.; Bjørk, R.; Smith, A.; Bahl, C.R.H. Optimally segmented permanent magnet structures. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2016, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, J.A.; Capovilla, M.S.; Trevizoli, P.V.; Engelbrecht, K.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Barbosa, J.R. Development of a novel rotary magnetic refrigerator. Int. J. Refrig. 2016, 68, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insinga, A.R.; Smith, A.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Nielsen, K.K.; Bjørk, R. Optimal segmentation of three-dimensional permanent-magnet assemblies. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2019, 12, 064034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niamjan, N.; Sirisathitkul, C.; Cheedket, S. Substitution effect of magnetic materials in Halbach cylinder for magnetic refrigerators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. A Phys. Sci. 2020, 90, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortkamp, F.P.; Lozano, J.A.; Barbosa, J.R. Analytical solution of concentric two-pole Halbach cylinders as a preliminary design tool for magnetic refrigeration systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 444, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørk, R.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Insinga, A.R. Topology optimized permanent magnet systems. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 437, 78685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Yoon, M.; Nomura, T.; Dede, E.M. Topology optimization for design of segmented permanent magnet arrays with ferromagnetic materials. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018, 449, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, S.; Kural, M.H. Octagonal Halbach magnet array design for a magnetic refrigerator. Heat Transf. Eng. 2018, 39, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.K.; Insinga, A.R.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Bjørk, R. Optimizing a Halbach cylinder for field homogeneity by remanence variation. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 514, 167175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gerlando, A.; Negri, S.; Ricca, C. A Novel Analytical Formulation of the Magnetic Field Generated by Halbach Permanent Magnet Arrays. Magnetism 2023, 3, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabachi, M.A.; Rahmouni, A.; Rusu, E.; Bouksour, O. Aerodynamic simulations for floating Darrieus-type wind turbines with three-stage rotors. Inventions 2020, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabachi, M.A.; Rouway, M.; Rahmouni, A.; Bouksour, O.; Sbai, S.J.; Laaouidi, H.; Tarfaoui, M.; Aamir, A.; Lagdani, O. Numerical investigation of the structural behavior of an innovative offshore floating Darrieus-type wind turbine with three-stage rotors. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabachi, M.A.; Rahmouni, A.; Bouksour, O. Design and Aerodynamic Performance of New Floating H-Darrieus Vertical Axis Wind Turbines. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 30, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, L.; Kevlishvili, N. Designing of Halbach cylinder based magnetic assembly for a rotating magnetic refrigerator. Part 1: Designing procedure. Int. J. Refrig. 2017, 73, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Chang, L.; Su, P.; Li, Y.; Hua, W.; Shen, Y. Research on High-Torque-Density Design for Axial Modular Flux-Reversal Permanent Magnet Machine. Energies 2023, 16, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Liu, B.; Dong, H. Research on Air Gap Magnetic Field Characteristics of Trapezoidal Halbach Permanent Magnet Linear Synchronous Motor Based on Improved Equivalent Surface Current Method. Energies 2023, 16, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, T.; Martinek, G.; Schneider, G.; Goll, D. The Field-Dependent Magnetic Viscosity of FeNdB Permanent Magnets. Materials 2024, 17, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | FeNdB | AISI 1010 |

|---|---|---|

| Remanence [T] | 1.44 | – |

| Coercivity [kA/m] | 836 | – |

| Relative permeability [-] | 1.04457 | 2000–5000 |

| Conductivity [S/m] | 265,000 | 6,000,000 |

| Density [kg/m3] | 7500 | 7870 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El Mortajine, C.; Dabachi, M.A.; Lakrit, S.; Oubnaki, H.; Faid, A.; Bouzi, M. Improving Designs of Halbach Cylinder-Based Magnetic Assembly with High- and Low-Field Regions for a Rotating Magnetic Refrigerator. Magnetism 2025, 5, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetism5040031

El Mortajine C, Dabachi MA, Lakrit S, Oubnaki H, Faid A, Bouzi M. Improving Designs of Halbach Cylinder-Based Magnetic Assembly with High- and Low-Field Regions for a Rotating Magnetic Refrigerator. Magnetism. 2025; 5(4):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetism5040031

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Mortajine, Chaimae, Mohamed Amine Dabachi, Soufian Lakrit, Hasnaa Oubnaki, Amine Faid, and Mostafa Bouzi. 2025. "Improving Designs of Halbach Cylinder-Based Magnetic Assembly with High- and Low-Field Regions for a Rotating Magnetic Refrigerator" Magnetism 5, no. 4: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetism5040031

APA StyleEl Mortajine, C., Dabachi, M. A., Lakrit, S., Oubnaki, H., Faid, A., & Bouzi, M. (2025). Improving Designs of Halbach Cylinder-Based Magnetic Assembly with High- and Low-Field Regions for a Rotating Magnetic Refrigerator. Magnetism, 5(4), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetism5040031