Digital Health Transformation Through Telemedicine (2020–2025): Barriers, Facilitators, and Clinical Outcomes—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the obstacles that prevented telemedicine from being widely adopted and effectively used during 2020–2025?

- (2)

- What are the main factors that contribute to the successful implementation of telehealth?

- (3)

- How did telemedicine impact clinical outcomes and healthcare utilization across different settings and patient groups?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- -

- Population (P): We included studies involving any patient population, including children and adults, across all healthcare settings. These settings encompassed primary care, specialty care, emergency departments, surgical follow-up, chronic disease management, mental health services, and maternal/perinatal care. Studies were eligible if conducted from January 2020 onward, during or after the COVID-19 pandemic, and the expansion of telemedicine.

- -

- Intervention (I): Telemedicine or telehealth delivered via video, telephone, messaging platforms, mobile applications, or remote patient monitoring.

- -

- Comparator (C): Comparators included traditional in-person care, no telehealth intervention, or descriptive studies without explicit comparators, such as those examining adoption, barriers, or facilitators.

- -

- Outcome (O): Clinical outcomes (disease control, hospitalization, emergency visits), process outcomes (follow-up adherence, utilization patterns, no-show rates), patient or provider experience outcomes (satisfaction, convenience, access), and identified barriers or facilitators of telehealth implementation.

- -

- Study (S): Only empirical primary studies published in English between 2020 and 2025 were included.

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

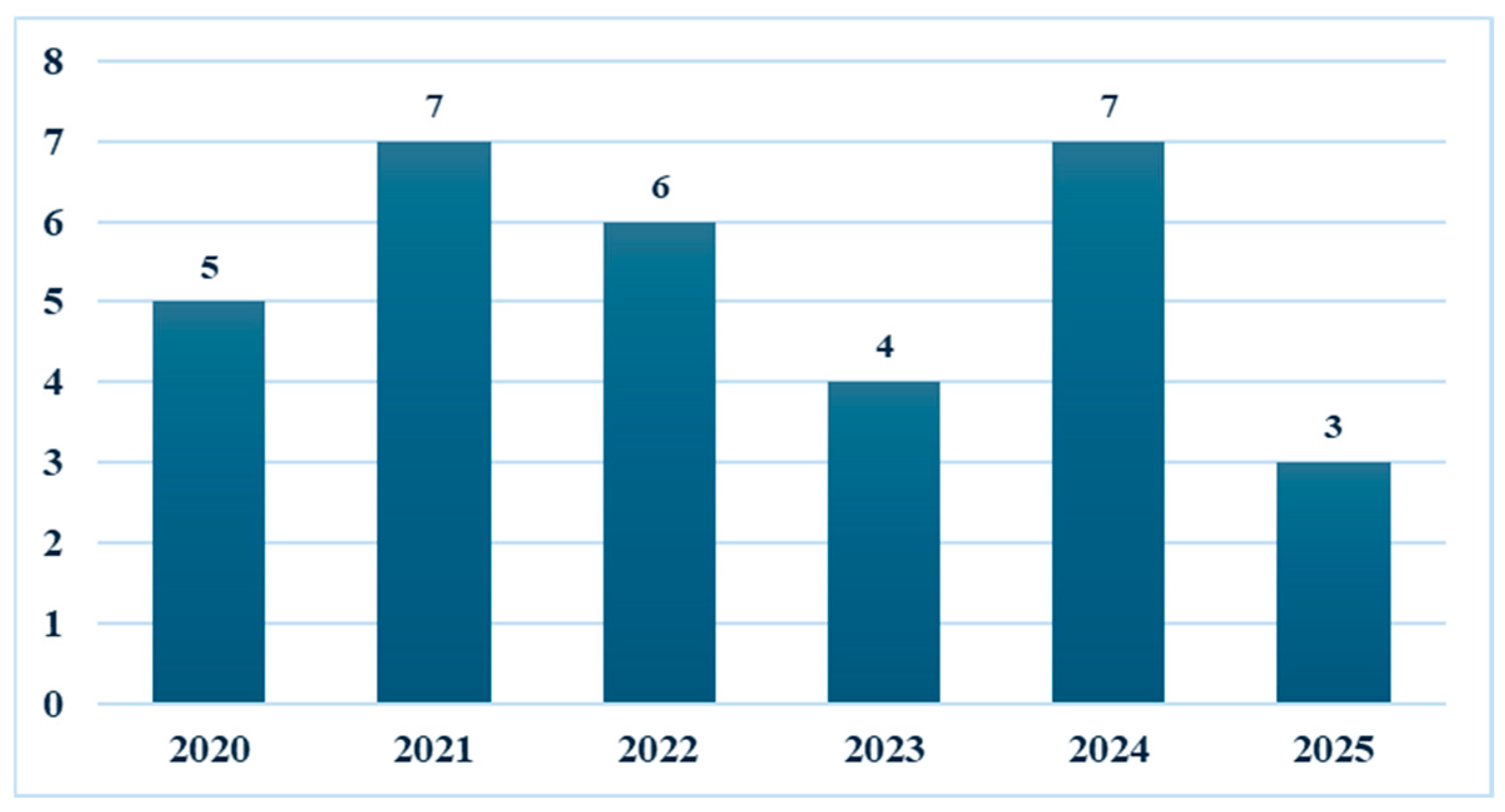

3.1. Study Characteristics

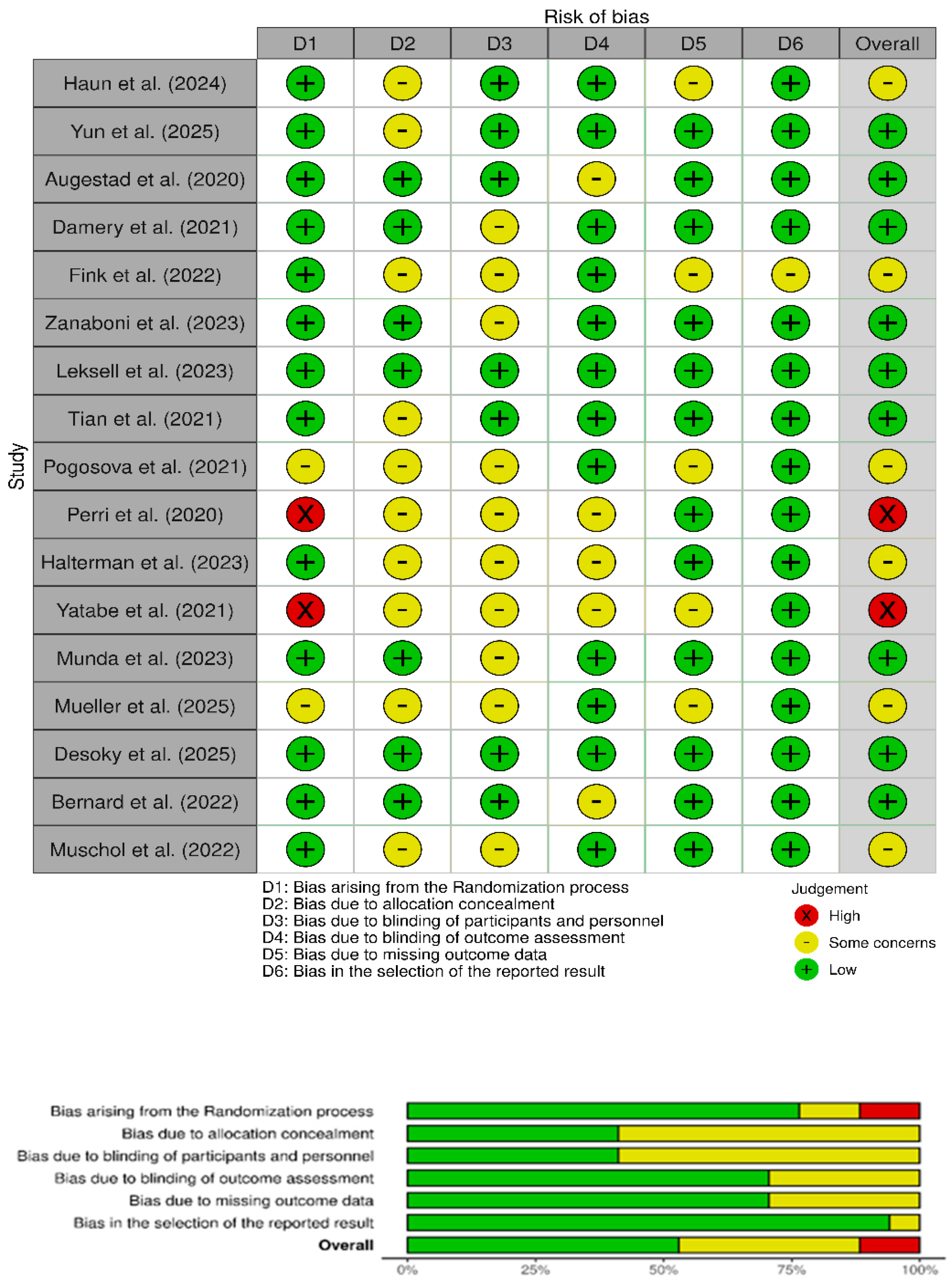

3.2. Risk of Bias

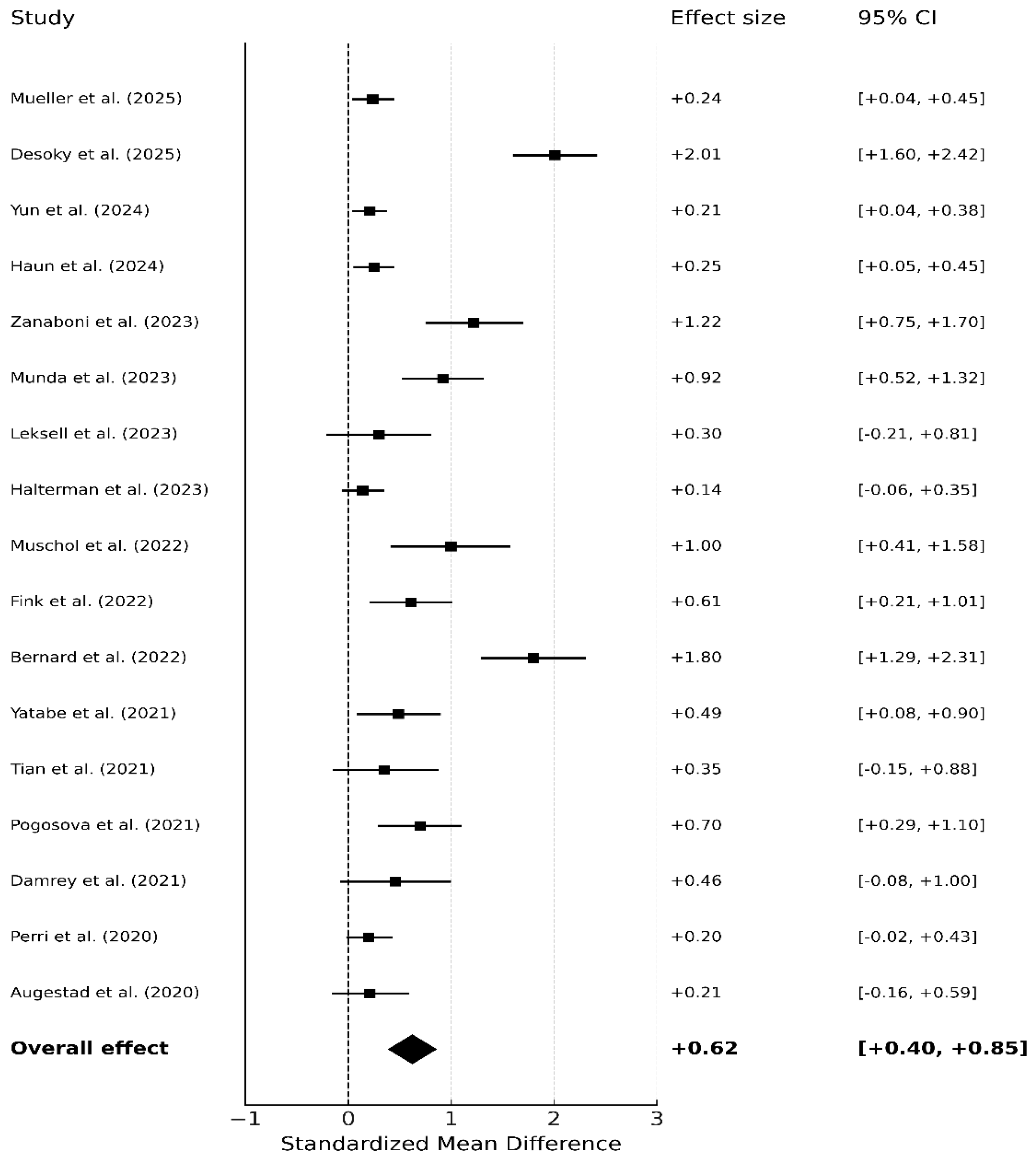

3.3. Global Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials (17 RCTs)

3.4. Regional Subgroup Results: European Randomized Trials (10 RCTs)

3.5. Regional Subgroup Results: Non-European Randomized Trials (7 RCTs)

3.6. Publication Bias

3.7. Heterogeneity (I2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

4.1.1. Chronic Disease Outcomes

4.1.2. Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes

4.1.3. Surgical and Post-Operative Outcomes

4.1.4. Patient-Reported Outcomes

4.1.5. System-Level Outcomes

4.1.6. Obstacles to Telemedicine Adoption

4.1.7. Facilitators of Successful Implementation

4.1.8. Effects on Outcomes and Usage

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shaver, J. The State of Telehealth Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim. Care 2022, 49, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omboni, S.; Padwal, R.S.; Alessa, T.; Benczúr, B.; Green, B.B.; Hubbard, I.; Kario, K.; Khan, A.N.; Konardi, A.; Logan, A.G.; et al. The worldwide impact of telemedicine during COVID-19: Current evidence and recommendations for the future. Connect. Health 2022, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet. 2020. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicinehealth-care-provider-fact-sheet (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. Maintaining Essential Health Services: Operational Guidance for the COVID-19 Context; Interim Guidance 1 June 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ezeamii, V.C.; Okobi, O.E.; Wambai-Sani, H.; Perera, G.S.; Zaynieva, S.; Okonkwo, C.C.; Ohaiba, M.M.; William-Enemali, P.C.; Obodo, O.R.; Obiefuna, N.G. Revolutionizing healthcare: How telemedicine is improving patient outcomes and expanding access to care. Cureus 2024, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, L.M. Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January–March 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1595–1599. [Google Scholar]

- Keesara, S.; Jonas, A.; Schulman, K. COVID-19 and health care’s digital revolution. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e82. [Google Scholar]

- Wosik, J.; Fudim, M.; Cameron, B.; Gellad, Z.F.; Cho, A.; Phinney, D.; Curtis, S.; Roman, M.; Poon, E.G.; Ferranti, J.; et al. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2020, 27, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, D.; Abernethy, A.; Butte, A.J.; Ginsburg, P.; Kocher, B.; Novelli, C.; Sandy, L.; Smee, J.; Fabi, R.; Offodile, A.C., II; et al. Telehealth and Mobile Health: Case Study for Understanding and Anticipating Emerging Science and Technology; National Academy of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wherton, J.; Greenhalgh, T.; Hughes, G.; Shaw, S.E. The role of information infrastructures in scaling up video consultations during COVID-19: Mixed methods case study into opportunity, disruption, and exposure. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e42431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Mosier, J.; Subbian, V. Identifying barriers to and opportunities for telehealth implementation amidst the COVID-19 pandemic by using a human factors approach: A leap into the future of health care delivery? JMIR Hum. Factors 2021, 8, e24860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuziemsky, C.; Hunter, I.; Udayasankaran, J.G.; Ranatunga, P.; Kulatunga, G.; John, S.; John, O.; Flórez-Arango, J.F.; Ito, M.; Ho, K.; et al. Telehealth as a means of enabling health equity. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2022, 31, 060–066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, I.J.B.D.; Abdulazeem, H.; Vasanthan, L.T.; Martinez, E.Z.; Zucoloto, M.L.; Østengaard, L.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Zapata, T.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. Barriers and facilitators to utilizing digital health technologies by healthcare professionals. NPJ Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 161. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A.; Bañez, L.L.; Huppert, J.; Iyer, S.; Chang, C.; Umscheid, C.A. AHRQ EPC Program Research Gaps Summary: Telehealth; Methods Research Report. AHRQ Publication No. 23-EHC015; AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/telehealth/research-report (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Shamseer, L.; Moher, D.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015, 349, g7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.T.; Zenker, A.; Saha, S.; Gerdtham, U.G.; Trepel, D. Economic evaluations of strategies targeting pre-diagnosis dementia populations: Protocol for a systematic review. HRB Open Res. 2025, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, M.R.; Tsalatsanis, A.; Chaphalkar, C.; Ivanova, J.; Ong, T.; Soni, H.; Barrera, J.F.; Wilczewski, H.; Welch, B.M.; Bunnell, B.E. Telemedicine appointments are more likely to be completed than in-person healthcare appointments: A retrospective cohort study. JAMIA Open 2024, 7, ooae059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardi, C.; Antonini, M.; Jordan, Z.; Wechtler, H.; Paolucci, F.; Hinwood, M. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of digital technologies in mental health systems: A qualitative systematic review to inform a policy framework. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.D.; Xia, B.; Dini, M.E.; Silverman, A.L.; Pierce, B.S.; Chang, C.N.; Perrin, P.B. Barriers and facilitators to physicians’ telemedicine uptake during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS Digit. Health 2025, 4, e0000818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 6.4; Cochrane: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/archive/v6.4/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Gao, Y.; Xiang, L.; Yi, H.; Song, J.; Sun, D.; Xu, B.; Zhang, G.; Wu, I.X. Confounder adjustment in observational studies investigating multiple risk factors: A methodological study. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montori, V.M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Adhikari, N.K.; Burns, K.E.; Eggert, C.H.; Briel, M.; Lacchetti, C.; Leung, T.W.; Darling, E.; Bryant, D.M.; et al. Randomized trials stopped early for benefit: A systematic review. JAMA. 2005, 294, 2203–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddar, J.M.; Viswanadham, R.V.; Levine, D.L.; Martinez, T.R.; Willis, K.; Choi, N.; Douglas, J.; Lawrence, K.S. Video-based telemedicine utilization patterns and associated factors among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods scoping review. PLoS Digit. Health 2025, 4, e0000952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeh, C.A.; Torbela, A.; Saigal, S.; Kaur, H.; Kazourra, S.; Gupta, R.; Shah, S. Telemonitoring in heart failure patients: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J. Cardiol. 2022, 14, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, N.M.; Vakkalanka, J.P.; Holcombe, A.; Carter, K.D.; McCoy, K.D.; Clark, H.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Merchant, K.A.; Bailey, G.J.; Ward, M.M. Effect of chronic disease home telehealth monitoring in the veterans health administration on healthcare utilization and mortality. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2023, 38, 3313–3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughman, D.J.; Jabbarpour, Y.; Westfall, J.M.; Jetty, A.; Zain, A.; Baughman, K.; Pollak, B.; Waheed, A. Comparison of quality performance measures for patients receiving in-person vs telemedicine primary care in a large integrated health system. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2233267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haun, M.W.; Tönnies, J.; Hartmann, M.; Wildenauer, A.; Wensing, M.; Szecsenyi, J.; Feißt, M.; Pohl, M.; Vomhof, M.; Icks, A.; et al. Model of integrated mental health video consultations for people with depression or anxiety in primary care (PROVIDE-C): Assessor masked, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2024, 386, e079921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.; Comín-Colet, J.; Calero-Molina, E.; Hidalgo, E.; José-Bazán, N.; Marcos, M.C.; Soria, T.; Llàcer, P.; Fernández, C.; García-Pinilla, J.M.; et al. Evaluation of mobile health technology combining telemonitoring and teleintervention versus usual care in vulnerable-phase heart failure management (HERMeS): A multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Digit. Health 2025, 7, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, M.G.; Shankar, M.N.; Daniels, M.J.; Durning, P.E.; Ross, K.M.; Limacher, M.C.; Janicke, D.M.; Martin, A.D.; Dhara, K.; Bobroff, L.B.; et al. Effect of telehealth extended care for maintenance of weight loss in rural US communities: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e206764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatabe, J.; Yatabe, M.S.; Okada, R.; Ichihara, A. Efficacy of telemedicine in hypertension care through home blood pressure monitoring and videoconferencing: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Cardio 2021, 5, e27347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Augestad, K.M.; Sneve, A.M.; Lindsetmo, R.O. Telemedicine in postoperative follow-up of STOMa PAtients: A randomized clinical trial (the STOMPA trial). J. Br. Surg. 2020, 107, 509–518. [Google Scholar]

- Pogosova, N.; Yufereva, Y.; Sokolova, O.; Yusubova, A.; Suvorov, A.; Saner, D.H. Telemedicine Intervention to Improve Long-Term Risk Factor Control and Body Composition in Persons with High Cardiovascular Risk: Results from a Randomized Trial: Telehealth strategies may offer an advantage over standard institutional based interventions for improvement of cardiovascular risk in high-risk patients long-term. Glob. Heart 2021, 16, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, F.; Ma, L. Comparing the efficacies of telemedicine and standard prenatal care on blood glucose control in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e22881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, L.; Valsecchi, V.; Mura, T.; Aouinti, S.; Padern, G.; Ferreira, R.; Pastor, J.; Jorgensen, C.; Mercier, G.; Pers, Y.M. Management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis by telemedicine: Connected monitoring. A randomized controlled trial. Jt. Bone Spine 2022, 89, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, T.; Chen, Q.; Chong, L.; Hii, M.W.; Knowles, B. Telemedicine versus face-to-face follow up in general surgery: A randomized controlled trial. ANZ J. Surg. 2022, 92, 2544–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muschol, J.; Heinrich, M.; Heiss, C.; Knapp, G.; Repp, H.; Schneider, H.; Thormann, U.; Uhlar, J.; Unzeitig, K.; Gissel, C. Assessing telemedicine efficiency in follow-up care with video consultations for patients in orthopedic and trauma surgery in Germany: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e36996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halterman, J.S.; Fagnano, M.; Tremblay, P.; Butz, A.; Perry, T.T.; Wang, H. Effect of the telemedicine enhanced asthma management through the Emergency Department (TEAM-ED) Program on asthma morbidity: A randomized controlled trial. J. Pediatr. 2024, 266, 113867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leksell, J.; Toft, E.; Rosman, J.; Eriksson, J.W.; Fischier, J.; Lindholm-Olinder, A.; Rosenblad, A.; Nerpin, E. Virtual clinic for young people with type 1 diabetes: A randomised wait-list controlled study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munda, A.; Mlinaric, Z.; Jakin, P.A.; Lunder, M.; Pongrac Barlovic, D. Effectiveness of a comprehensive telemedicine intervention replacing standard care in gestational diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Diabetol. 2023, 60, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaboni, P.; Dinesen, B.; Hoaas, H.; Wootton, R.; Burge, A.T.; Philp, R.; Oliveira, C.C.; Bondarenko, J.; Tranborg Jensen, T.; Miller, B.R.; et al. Long-term telerehabilitation or unsupervised training at home for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desoky, A.A.; Mostafa, N.M.; AbdEllah-Alawi, M.H.; Hashem, E.M. Telehealth and challenges of statin adherence in patients with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.; Dinges, S.M.; Gass, F.; Fegers-Wustrow, I.; Treitschke, J.; von Korn, P.; Boscheri, A.; Krotz, J.; Freigang, F.; Dubois, C.; et al. Telemedicine-supported lifestyle intervention for glycemic control in patients with CHD and T2DM: Multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damery, S.; Jones, J.; O’Connell Francischetto, E.; Jolly, K.; Lilford, R.; Ferguson, J. Remote consultations versus standard face-to-face appointments for liver transplant patients in routine hospital care: Feasibility randomized controlled trial of myVideoClinic. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e19232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.C.; Tajanlangit, M.; Heyward, J.; Mansour, O.; Qato, D.M.; Stafford, R.S. Use and content of primary care office-based vs telemedicine care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2021476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillion, M.H.; Parlow, J.; Borges, F.K.; Marcucci, M.; Jacka, M.; Adili, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Ouellette, C.; Bird, M.; Ofori, S.; et al. Post-discharge after surgery Virtual Care with Remote Automated Monitoring-1 (PVC-RAM-1) technology versus standard care: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2021, 374, n2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremades, M.; Ferret, G.; Parés, D.; Navinés, J.; Espin, F.; Pardo, F.; Caballero, A.; Viciano, M.; Julian, J.F. Telemedicine to follow patients in a general surgery department. A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Surg. 2020, 219, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhu, Z.; Thompson, M.P.; McCullough, J.S.; Hou, H.; Chang, C.H.; Fendrick, A.M.; Ellimoottil, C. Primary care practice telehealth use and low-value care services. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2445436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, V.V.; Villaflores, C.W.; Chuong, L.H.; Leuchter, R.K.; Kilaru, A.S.; Vangala, S.; Sarkisian, C.A. Association between in-person vs telehealth follow-up and rates of repeated hospital visits among patients seen in the emergency department. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2237783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberly, L.A.; Kallan, M.J.; Julien, H.M.; Haynes, N.; Khatana, S.A.; Nathan, A.S.; Snider, C.; Chokshi, N.P.; Eneanya, N.D.; Takvorian, S.U.; et al. Patient characteristics associated with telemedicine access for primary and specialty ambulatory care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2031640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuttner, L.; Mayfield, B.; Jaske, E.; Theis, M.; Nelson, K.; Reddy, A. Primary Care Telehealth Initiation and Engagement Among Veterans at High Risk, 2019–2022. JAMA Netw. Open. 2024, 7, e2424921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyte, A.; Mehrotra, A.; Wilcock, A.D.; SteelFisher, G.K.; Grabowski, D.C.; Barnett, M.L. Telemedicine visits in US skilled nursing facilities. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2329895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.Y.; Rose, S.; Barnett, M.L.; Huskamp, H.A.; Uscher-Pines, L.; Mehrotra, A. Community factors associated with telemedicine use during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2110330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilhou, A.S.; Jain, A.; DeLeire, T. Telehealth expansion, internet speed, and primary care access before and during COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2347686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, M.; Huang, J.; Graetz, I.; Muelly, E.; Millman, A.; Lee, C. Treatment and follow-up care associated with patient-scheduled primary care telemedicine and in-person visits in a large integrated health system. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2132793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Lynch, C.; Gordon, H.; Coffey, C.E.; Canamar, C.P.; Tangpraphaphorn, S.; Gonzalez, K.; Mahajan, N.; Shoenberger, J.; Menchine, M.; et al. Virtual home care for patients with acute illness. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2447352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapham, G.T.; Hyun, N.; Bobb, J.F.; Wartko, P.D.; Matthews, A.G.; Yu, O.; McCormack, J.; Lee, A.K.; Liu, D.S.; Samet, J.H.; et al. Nurse care management of opioid use disorder treatment after 3 years: A secondary analysis of the PROUD cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2447447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatef, E.; Lans, D.; Bandeian, S.; Lasser, E.C.; Goldsack, J.; Weiner, J.P. Outcomes of in-person and telehealth ambulatory encounters during COVID-19 within a large commercially insured cohort. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e228954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.Y.; Ng, S.; Zhu, Z.; McCullough, J.S.; Kocher, K.E.; Ellimoottil, C. Association between primary care practice telehealth use and acute care visits for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions during COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e225484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.Y.; Mehrotra, A.; Huskamp, H.A.; Uscher-Pines, L.; Ganguli, I.; Barnett, M.L. Variation in telemedicine use and outpatient care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: Study examines variation in total US outpatient visits and telemedicine use across patient demographics, specialties, and conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Combined Search Term | Limits |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((Telemedicine OR Telehealth OR “Remote Consultation” OR “Digital Health”) OR (telemedicine OR telehealth OR “virtual care” OR “remote consultation” OR “digital health”)) AND ((COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR Coronavirus) OR (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus OR pandemic)) | English; 2020–2025 |

| Embase | ((‘telemedicine’ OR ‘telehealth’ OR ‘remote consultation’ OR ‘digital health’) OR (telemedicine OR telehealth OR “virtual care” OR “remote consultation” OR “digital health”)) AND ((‘COVID-19’ OR ‘SARS-CoV-2’ OR ‘coronavirus’) OR (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus OR pandemic)) | English; 2020–2025 |

| Web of Science | (telemedicine OR telehealth OR “virtual care” OR “remote consultation” OR “digital health”) AND (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus OR pandemic) | English; 2020–2025 |

| Scopus | (telemedicine OR telehealth OR “virtual care” OR “remote consultation” OR “digital health”) AND (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus OR pandemic) | English; 2020–2025 |

| PsycINFO | ((telemedicine OR telehealth OR “remote consultation” OR “digital health” OR “virtual care”) AND (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus OR pandemic)) | English; 2020–2025 |

| Publication Bias | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | Z | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||||||

| Egger’s Regression test | Intercept | 4.56 | 1.37 | 1.65 | 7.47 | 3.34 | 0.004 |

| Slope | –0.24 | 0.21 | –0.68 | 0.21 | –1.13 | 0.278 | |

| Publication Bias | Hedge’s g | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| Trim and fill | Original | 0.62 | 0.40 | 0.85 |

| Corrected | 0.57 | 0.31 | 0.83 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rabbani, M.G.; Alam, A.; Prybutok, V.R. Digital Health Transformation Through Telemedicine (2020–2025): Barriers, Facilitators, and Clinical Outcomes—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5040206

Rabbani MG, Alam A, Prybutok VR. Digital Health Transformation Through Telemedicine (2020–2025): Barriers, Facilitators, and Clinical Outcomes—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Encyclopedia. 2025; 5(4):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5040206

Chicago/Turabian StyleRabbani, Md Golam, Ashrafe Alam, and Victor R. Prybutok. 2025. "Digital Health Transformation Through Telemedicine (2020–2025): Barriers, Facilitators, and Clinical Outcomes—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Encyclopedia 5, no. 4: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5040206

APA StyleRabbani, M. G., Alam, A., & Prybutok, V. R. (2025). Digital Health Transformation Through Telemedicine (2020–2025): Barriers, Facilitators, and Clinical Outcomes—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Encyclopedia, 5(4), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/encyclopedia5040206