Definition

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected every aspect of people’s lives across the globe. It is also unique in the way it changed their lives. In this entry, a framework, the Transition Theory, is outlined, which is used to interpret the transitional properties of this pandemic, the ways it differs from other transitional events, and how it impacts the lives and well-being of the individuals. The prediction is that people might consider the pandemic as an important life transition event only if there is a little similarity between their pre-pandemic and post-pandemic lives. Individual differences also need to be considered as those whose lives have been directly affected by the pandemic experience a greater COVID-related change (e.g., job loss vs. no job loss). Lastly, the transitional impact of the pandemic might have a strong link with people’s mental outcomes. These notions call for a longitudinal approach to get an accurate understanding of the pandemic experience while this world-changing event unfolds rather than in retrospect.

1. Introduction

In December 2019, the world saw the emergence of a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) which the World Health Organization (WHO) officially labeled a pandemic on 11 March 2020 [1]. As of May 2022, over 500 million positive cases and over 6 million deaths were recorded [2]. To curb the spread of the virus, isolation, social distancing, and other restrictions were put in place [3,4]. As a result, people had to reconfigure aspects of their environments and their routines to adapt to the pandemic-related changes they were experiencing (e.g., online classes, work from home). Furthermore, people’s economic stability had a hard hit as financial markets fell and unemployment rates rose. Thus, the pandemic affected life across the globe to some extent in terms of their financial, social, and day-to-day activities. In addition, the pandemic came to dominate the news cycle and social interaction [5,6].

Given the breadth and scope of the pandemic, it is intuitively clear that the pandemic has created a “new normal”, or a pandemic period [7]. Considering life events that require an adjustment in a person’s accustomed way of life, the COVID-19 pandemic could undoubtedly be counted as one of the most important life events or, in other words, an event of transition that has significantly impacted the lives of people from around the world. How the pandemic has changed people’s lives, the nature and extent of these changes, and the effect these changes have had on people’s well-being are less clear. It is relatively early to provide a complete empirical explanation of these issues, but given what we know about life transitions, their aspects of it, and their impact on the well-being status [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18], it is possible to speculate about them in an informed manner. This entry, speaking in broader terms, aims to explain whether the COVID-19 pandemic could be considered a distinctive (life) transition, and its qualitative impact. This is discussed in a few different steps: first, a theoretical framework, the Transition Theory, is outlined, which provides means for understanding the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic as a transitional event; second, discussed how the pandemic appears to be different from other transitional life events; finally, to take into account how the pandemic has been likely to affect people’s lives, memories, and well-being.

2. Overview of the Transition Theory—Definition of Transition and Its Properties

According to the Transition Theory [7,17,19,20], a transition is an event or series of events that causes fundamental changes in the “fabric of daily life”—what people do, where they do it, and with whom. During regular periods, when life is relatively stable, we spend most of our time engaging in mundane activities (e.g., commuting, and socializing) [21,22]. During a transition, this stability is interrupted. As a result, the familiar elements (e.g., people, location, objects) of our lives are removed, partially or fully. At the same time, we are introduced to a new set of life elements, marking the beginning of a new period in our lives and the end of the old one. Over time and with repeated exposure, some of these new elements might become familiar and eventually come to represent life, hence, defining the post-transitional period [7,20].

To explain this notion, two separate examples are provided. First, a person who has immigrated to another country has to go through a significant transition, as they have left their stable life behind (e.g., a graduate in the USA) and ended up in a different country with a different role (e.g., a lecturer in the UK). This introduces a new set of life elements (e.g., new neighbors, new stores) which, due to recurrent exposure, leads them towards a new stable post-transitional life period. Second, an individual went on a trip to Japan which introduced another set of novel life elements, but unlike the first example, these new elements had no lasting effect. This was because, at one point, the vacation was over, the individual came back home, and life returned to its normal course. Thus, rather than a stable post-transition period, a “brief interlude” was created. It is important to keep in mind that some of the life elements at any given point are always familiar (e.g., the spouse, the children, the exercise) while others are novel (e.g., a new colleague, a new cafe). That being said, some familiar elements from the pre-transitional period are retained across the transition while others are not (abandoned). Eventually, the post-transitional period should give rise to a new set of familiar life elements.

Hence, the transition could be understood from two aspects. One, where the post-transitional period is very much similar to the pre-transitional period, i.e., the retained life elements are many and the abandoned and/or new elements are few. Two, when pre- and post-transitional periods are very different, i.e., the retained elements are few and the abandoned and/or new elements are many. Thus, numerically speaking, transitions could affect lives through the process of addition (i.e., yielding larger new elements), subtraction (yielding smaller retained elements and larger abandoned elements), or both [7].

Assessment of the Impact of a Transition—Transitional Impact Scale

Since its development, the Transitional Impact Scale (TIS-12) has been used by researchers to assess how candidate transitional events impact the lives of people [15,16,18,23,24,25]. This 12-item TIS separately evaluates the material and psychological impacts of a transitional event, together explaining the overall changes brought to a person’s life. Material impacts indicate the adjustment people have to make to their way of living, including changes in their residence, possessions, day-to-day activities, and people with whom they socialize. Psychological changes concern changes in people’s beliefs, life viewpoints, attitudes, self-perception, ethics, and morality. For each TIS item, such as “This event has changed the activities I engage in,” the participants had to rate their agreement on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). In theory, if an event scores higher than three (neutral), that indicates a moderate impact on life at the minimum. In general, major transitions that define important life chapters, e.g., immigration, tend to elicit TIS scores of 4.0 or higher [16,18,23,25,26].

The overall impact of a transitional event on an individual’s life is determined by material and psychological changes brought by that event. These two types of changes are to some degree independent, such that psychological change can occur in the absence of material change. For instance, a religious conversion after experiencing trauma would be an example of a dramatic psychological change but a weak material change [15,24]. In contrast, high degrees of material change tend to correspond to high degrees of psychological change, e.g., immigration [27].

While measuring the transitional impact of an event, individual differences also need to be considered. For example, “starting university” might be considered a more impactful transition for the students who left their homes and live in a university dormitory (“dormies”) compared to the students who continue living with their parents (“homies”). Likewise, for those immigrating from one country to another, relocation might be a more influential transition in contrast to those relocating within the same state, i.e., from one city to another.

3. COVID-19 Pandemic as an Event of Transition—Features, Assessment, and Scope

The pandemic has caused a substantial change in people’s personal, social, and economic life as people have been facing isolation, concern about being infected, life activities, and work-related disruption [28,29,30,31,32]. Some of the changes, especially during the early days of the pandemic, have entailed the move of learning and office work online, closure of retail establishments, cancellation of all recreational activities and social gatherings, people being forced to stay in and as a result, spending more time on social media, and so on. Thus, considering its near-universal scope, this pandemic could be seen as a potentially important, and possibly the largest collective transition of all time [6,7].

Broadly speaking, this pandemic is unique in the way it has affected people’s lives. On the one hand, given its pervasive nature, the pandemic should have brought marked changes to everyone’s regular lives. On the other hand, the pandemic is likely to affect the lives of some people more than those of others. For example, the widespread job loss during the pandemic or at least in its early phase; people who have lost their jobs should, on average, experience greater COVID-related changes than those who have not [6,28]. These points are further elaborated below.

3.1. Difference between the COVID-19 Transition and Other Life Transitions

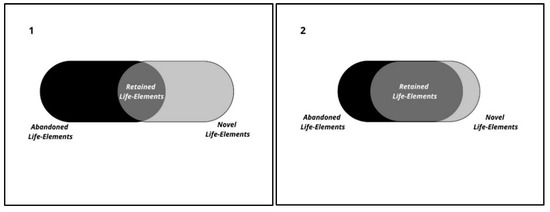

Usually, a transition involves the accumulation of changes in a person’s life, that is, replacement of old life elements with new ones, e.g., house, shops, neighbors (Figure 1, Panel 1), but one of the atypical features of the COVID-19 pandemic is that it appears to have altered our lives by narrowing them. Simply put, at least during the lockdown, the new normal differed from the old one by largely limiting what we could do and where we could do it. This led us to experience a unique type of transition—“transition-by-omission”—where the set of abandoned familiar elements was much greater than the new set of life elements (Figure 1, Panel 2).

Figure 1.

Transition—life elements are replaced, e.g., immigration (Panel 1). Transition—life elements are omitted/excluded, e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic (Panel 2).

The notion that the COVID-19 pandemic onset was experienced as transition-by-omission as supported by a recent study where 1215 North Americans responded to an online survey [6]. A couple of findings were particularly interesting. First, Cronbach’s Alpha of this TIS scale usually ranges from 0.80 to 0.90 [15,24], indicating that major life transitions, such as relocation, typically bring about a synchronized change in many aspects of a person’s life. On the other hand, the pandemic produced a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.60, implying that some elements of a person’s life were changing but others were not. This point was explained in the second finding. Two of the five items of the material TIS which concerned the activities people engaged in (mean = 3.95) and the places where they spent their time (mean = 3.33) received moderately high scores. The other items, which concerned people (mean = 2.87), belongings (mean = 1.98), and general material circumstances (mean = 2.76), produced ratings at or below the midpoint of the scale. One way to interpret these findings is that, at the outset of the pandemic, many areas went into lockdown. As a result, people could not go where they had been going previously and could not do what they had been doing previously. However, people were, for the most part, still living in the same place they had been living before the pandemic and were spending time with a subset of people with whom they had already been familiar (e.g., family members). Thus, these data indicate that the fabric of daily life has changed for many people, but it was not changed in a wholesome manner [6,7].

In terms of psychological change, people provided moderately high ratings for three out of five items. These concerned attitudes (mean = 3.47), emotional response (mean = 3.43), and thoughts about different things in their lives (mean = 3.71). The other two items, which addressed the sense of self (mean = 2.99) and an understanding of right and wrong (mean = 2.13), received ratings at or below the midpoint of the scale. One explanation could be that the unprecedented nature of the pandemic has caused people to be distressed and have negative affective thoughts. Thus, people have reacted to this atypical period by reevaluating their feelings, thoughts, and perspective towards life, which has brought about a considerable amount of psychological change [6,33].

Therefore, from the Transition Theory perspective, many people have gone through a relatively brief and shallow adjustment period, such as those who have retained their employment, their house, and/or continued their studies during the pandemic. More specifically, these people have faced a decline of familiar elements in their stable daily life to some level, but a moderate increase after some time. This decline was the result of introducing a fair number of new elements (e.g., online classes, video meetings, masks) and a notable decrease in the number of familiar elements (e.g., in-person classes, social gatherings). The stability in life was expected to return rather quickly because life under lockdown tends to be largely repetitive. As a result, the newly introduced life elements should lose their novelty fast. It is true that the pandemic has been disruptive, but compared to other life-changing events (e.g., relocation to a foreign country), life during the pandemic was quite similar to the pre-pandemic one, at least from a materialistic viewpoint (e.g., family dinner, living place, etc.).

3.2. COVID-19 Transition—Period of Enduring or an Interlude?

Public events sometimes define the lifetime periods of individuals [18,20,34,35,36,37]. This would only happen when a population undergoes a major “collective transition”, a transition that brings rapid, fundamental, and enduring changes in the lives of all affected people [7,17,18]. Typically, after this transition, there is a sharp decrease in the stability of people’s lives, and this instability sometimes lasts for an extended period. This, in turn, would lead to the gradual establishment of the post-transitional life period which is often different from the earlier (pre-transitional) life period.

During the pandemic or at least at the outset, several billion people have been under lockdown, isolation, or quarantine. The lives these people were living (or are still living) have been different to some extent from the lives they lived before the pandemic. Therefore, the novel coronavirus produced the largest collective transition of all time, at least in the numerical sense. A couple of questions come forward– in the future, will people frequently mention the pandemic while talking about different events from their lives (e.g., “this happened before COVID”)? Will people consider the pandemic as an important period and, therefore, think of it as of one of their major life events? [17,38,39,40,41,42]. The answers lie in the prediction of how people might remember the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their lives. Prior studies demonstrated that even very important public events (e.g., the 9/11 attacks and the collapse of the Soviet Union) were not regarded as major life events as they did not bring “fundamental and enduring changes” in the lives of all the people who were affected [23,35,36].

Therefore, to speculate whether this COVID-19 transition would be long-standing or just a period of exceptional experience, it is necessary to consider the level of fundamental and enduring changes it brings to people’s lives. It is apparent that we are living in a period of new normal that is at least moderately stable and somewhat different from the pre-COVID-19 period. It is also evident that regardless of its near-universal scope, the immediate effect of the pandemic was largely different from one place to another (e.g., in Mexico with a 5.6% case–fatality ratio vs. Japan with a 0.4% case–fatality ratio) [43], from one person to another (e.g., a laid-off restaurant worker vs. a faculty member working from home), and from one timepoint to another (before lockdown vs. after lockdown). The degree to which the life after the pandemic, which may also be called as the next new normal, would be different from the pre-pandemic period. This is a crucial point, as not all transitional events are counted as important; rather, only some distinct, identifiable periods should become a significant part of a person’s life. Generally speaking, from the viewpoint of the Transition Theory, a transition is considered important and life-altering when it produces a long-lasting effect and shapes the course of an individual’s life [18,40,41,44,45,46]. Thus, in other words, if a person’s post-pandemic life is quite similar to his or her pre-pandemic life, they might well remember the pandemic as a notable period, but retrospectively, should not consider it to be a major life-changing event. Rather, they should regard the Pandemic period more as an extended interlude (e.g., an exchange semester in a foreign country) [7]. The intuition here is that if the pandemic could not produce fundamental and enduring changes in the fabric of daily life of an individual, in a general sense, it should not be marked as one of the most important life-changing events or transitional events of this individual.

Lastly, as mentioned earlier, the COVID-19 pandemic could be seen as an extensive collective transition from a historical viewpoint. It should be mentioned that the Transition Theory treats the personal and collective transition similarly. Thus, as the theory predicts, like any other transition, the COVID-19 pandemic will be considered a major life event only if it brings about a fundamental change in a person’s life. This should be true regardless of the pandemic’s scope, its cultural and historical importance [18,19,20]. If those aforementioned social aspects of the pandemic play a significant role in deciding whether the COVID-19 period will be regarded as a major event in an individual’s life, then keeping the effect of the transition fixed, this COVID-19 period should be common in the regions where the pandemic had a hard hit and less common in relatively unaffected areas. In another scenario, given the pandemic’s breadth and scope, there is a possibility that the ‘life at the time of the pandemic’ might be a lasting conversational topic for everyone, even for those who were less affected or unaffected, marking it as an important life event [47,48].

3.3. Functionality of the TIS—Measuring the Transitional Impact of the Pandemic

People experiencing transitions after major events (e.g., wars, disasters) have to leave their old routines, take part in many one-off events, and have many first-time experiences [49,50]. Likewise, in this pandemic, everyone has had several COVID-19-related first-time experiences, such as online learning, cleaning routine, remote working, sanitization, etc. As discussed earlier, in its near-universal scope, the pandemic, at least at the outset, changed our lives in terms of the activities we do, the people we spend time with, the places we visit, our thoughts, emotions, etc. Hence, the abovementioned Transitional Impact Scale is a useful measurement tool to identify and assess the material and psychological aspects of an individual’s life that has changed due to the pandemic, simultaneously indicating its transitional properties. In line with the Transition Theory, it is reasonable to expect that those who have experienced a greater COVID-19-related change should produce a higher TIS rating than those who have not. This notion was supported by a recent web-based study [6] where those who lost their job as a direct result of the pandemic provided a higher material and psychological TIS rating than those who did not (Table S1). In the research setting, the transitional impact of the pandemic could also be measured by asking participants to provide an open-ended narrative about their pandemic-related experience in combination with TIS [7,33,41,51]. This mixed approach has a merit of overcoming the limitation posed by rating-based instruments alone as responses are collected in an unsolicited manner [32]. People might describe in detail how the pandemic has disrupted their lives by restricting where and what they could do, whom they could meet, changing goals and plans, and experiencing poor emotions [33], increasing the external validity of TIS.

Association with Well-Being Consequences

Prior studies have demonstrated that major life transitions also affect people’s overall well-being [8,11,13,14]. To elaborate on that, life transitions or public transitional events could be very stressful, and that links transitional events to mental health issues [52]. Considering the COVID-19 pandemic, as per the Transition Theory, an event of a transition, it brought about a sudden end to routine life and led to a different one, at least during its onset. This adjustment with sudden/new changes (aka transition) is related to a poor well-being outcome [28,29,30]. Given that the pandemic has generated a great deal of uncertainty and uneasiness [53,54], many have indicated that life during the pandemic is depressing, anxiety-provoking, and stressful [31,55,56]. Especially those whose lives have been directly affected by the pandemic (e.g., residence-displaced, study-disrupted, business-folded) have experienced amplified negative well-being [57,58,59]. Thus, it could be understood that there is potentially a strong link between the transitional impact of the pandemic and the psychological distress it caused. In numeric terms, the TIS rating, particularly, the material TIS should be a robust predictor of well-being measures, indicating that people have an adverse reaction to the negative consequences of their changing life circumstances [6]. This implies that the TIS instrument could not only identify the quantity and quality of changes brought by the pandemic experience, but also their relation to mental outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD evoked by the pandemic [24].

3.4. Future Scope of Research

The unusual feature of this pandemic has the potential to attribute to extending the Transition Theory [7,20]. One possible way to do this is by comparing the TIS ratings between two groups—one who have lost their job and the other who have lost their close ones, both as a direct consequence of the pandemic. The aim is to see which group will be more likely to consider the COVID-19 pandemic as a major event in their life period. The expectation is that the job loss group should provide a significantly higher rating in the material and psychological subscale of TIS than the loss of close others group. This is because the job loss group should experience both higher material and psychological change compared to those who have lost their significant ones (high psychological but relatively low material change). More concretely, if the material impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is stronger than its psychological impact, then this should demonstrate that the COVID-19 pandemic satisfies the definition of major life transitions provided by the Transition Theory [15,16,24].

4. Conclusions

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic is distinctive in many ways in its near-universal scope and the way it has affected our lives to various degrees—permanently altering for some while temporarily changing for others. The Transition Theory provides an explanation to understand at least some of its uniqueness. From this perspective of the Transition Theory, the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic can be denoted as a transition by omission, one that has engendered a relatively shallow decline and then a sharp increase in the steadiness of a person’s life, leading to a somewhat stable pandemic period. The speculation here is that people will consider the pandemic to be an important transition period only if their pre-pandemic and post-pandemic lives are less similar; or else, this pandemic period will be regarded as an extended interlude [7]. Nevertheless, the COVID-19 pandemic will be viewed as a significant event leaving an impression on people’s lives. What is less clear is how this pandemic-specific transition will continue to impact the lives of individuals. The authors believe that there will be a long-term impact of the pandemic as sometimes people’s immediate and later reaction to a crisis varies in degrees, especially when that crisis keeps affecting their lives. In other words, the pandemic could pose a nonlinear trajectory as at one-point people might start returning to their normal life. Short-term approaches like cross-sectional studies have shortcomings in their capacity of measuring this “change over time” trend or the cumulative effect of the pandemic. This is because they are carried out at a one-time point or over a short period which makes it difficult to determine the temporal link between the pandemic and its associated changes [60]. This notion calls for a longitudinal approach to assess the pandemic’s transitional impact because over time, some people get accustomed to a relatively small adjustment to their routines while others scramble with radical life changes. Understanding this particular differential impact could provide a guiding framework of developing a tailored distress-specific intervention which would not only have the value of dealing with the ongoing pandemic, but also of addressing future ones.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/encyclopedia2030109/s1, Table S1: Average ratings on COVID-TIS from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.Z.H. and N.R.B.; methodology, E.Z.H. and T.U.; writing—original draft preparation, E.Z.H.; writing—review and editing, T.U. and N.R.B.; visualization, E.Z.H.; supervision, N.R.B. and T.U.; funding acquisition, N.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the third author’s Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant, RES0038944.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 [Speech Transcription]. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-openingremarks-at-the-mediabriefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, S.Y.; Gao, R.D.; Chen, Y.L. Fear can be more harmful than the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in controlling the corona virus disease 2019 epidemic. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 652–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, S.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Han, C. The Effects of Social Media Use on Preventive Behaviors during Infectious Disease Outbreaks: The Mediating Role of Self-relevant Emotions and Public Risk Perception. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heanoy, E.Z.; Shi, L.; Brown, N.R. Assessing the Transitional Impact and Mental Health Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic Onset. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.R. The possible effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the contents and organization of autobiographical memory: A Transition-Theory perspective. Cognition 2021, 212, 104694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, T.H.; Rahe, R.H. The social readjustment rating scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 1967, 11, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyler, A.R.; Masuda, M.; Holmes, T.H. Magnitude of life events and seriousness of illness. Psychosom. Med. 1971, 33, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarason, I.G.; Johnson, J.H.; Siegel, J.M. Assessing the impact of life changes: Development of the life experiences survey. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1978, 46, 932–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, B. Life transitions, role histories, and mental health. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1990, 55, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.J.; Wheaton, B. The assessment of stress using life events scale. In Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists; Cohen, S., Kessler, R.C., Gordon, L.U., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. Transitions and turning points in developmental psychopathology: As applied to the age span between childhood and mid-adulthood. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1996, 19, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, C. Life events, stress and depression: A review of recent findings. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2002, 36, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svob, C.; Brown, N.R.; Reddon, J.R.; Uzer, T.; Lee, P.J. The transitional impact scale: Assessing the material and psychological impact of life transitions. Behav. Res. Methods 2014, 46, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Brown, N.R. The effect of immigration on the contents and organization of autobiographical memory: A transition-theory perspective. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2016, 5, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.R.; Schweickart, O.; Svob, C. The effect of collective transitions on the organization and contents of autobiographical memory: A transition theory perspective. Am. J. Psychol. 2016, 129, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Tse, C.S.; Brown, N.R. The effects of collective and personal transitions on the organization and contents of autobiographical memory in older Chinese adults. Mem. Cogn. 2017, 45, 1335–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.R.; Hansen, T.G.B.; Lee, P.J.; Vanderveen, S.A.; Conrad, F.G. Historically defined autobiographical periods: Their origins and implications. In Under-Standing Autobiographical Memory: Theories and Approaches; Berntsen, D., Rubin, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 160–180. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, N.R. Transition theory: A minimalist perspective on the organization of autobiographical memory. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2016, 5, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Krueger, A.B.; Schkade, D.A.; Schwarz, N.; Stone, A.A. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science 2004, 306, 1776–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Dolan, P. Accounting for the richness of daily activities. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourkova, V.V.; Brown, N.R. Assessing the impact of “The Collapse” on the organization and content of autobiographical memory in the former Soviet Union. J. Soc. 2015, 71, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzer, T. Validity and reliability testing of the transitional impact scale. Stress. Health 2020, 36, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzer, T.; Beşiroğlu, L.; Karakılıç, M. Event centrality, transitional impact and symptoms of posttraumatic stress in a clinical sample. Anxiety Stress Coping 2020, 33, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzer, T.; Brown, N.R. Disruptive individual experiences create lifetime periods: A study of autobiographical memory in persons with spinal cord injury. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 2015, 29, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svob, C.; Brown, N.R. Intergenerational transmission of the reminiscence bump and biographical conflict knowledge. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, K.M.; Harris, C.; Drawve, G. Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tull, M.T.; Edmonds, K.A.; Scamaldo, K.M.; Richmond, J.R.; Rose, J.P.; Gratz, K.L. Psychological outcomes associated with stay-at-home orders and the perceived impact of COVID-19 on daily life. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 289, 113098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemura, J.; Ursano, R.J.; Morganstein, J.C.; Kurosawa, M.; Benedek, D.M. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.P.H.; Hui, B.P.H.; Wan, E.Y.F. Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, B.R.; Torossian, E. Older adults’ experience of the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods analysis of stresses and joys. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heanoy, E.Z.; Nadler, E.H.; Lorrain, D.; Brown, N.R. Exploring People’s Reaction and Perceived Issues of the COVID-19 Pandemic at Its Onset. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, A.; Habermas, T. Living in history and living by the cultural life script: How older Germans date their autobiographical memories. Memory 2016, 24, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, N.R.; Lee, P.J. Public events and the organization of autobiographical memory: An overview of the Living-in-History Project. Behav. Sci. Terror. Political Aggress. 2010, 2, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.R.; Lee, P.J.; Krslak, M.; Conrad, F.G.; Hansen, T.; Havelka, J.; Reddon, J.R. Living in history: How war, terrorism, and natural disaster affect the organization of autobiographical memory. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebian, S.; Brown, N.R. Living in history in Lebanon: The influence of chronic social upheaval on the organization of autobiographical memory. Memory 2014, 22, 194–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, W.J. Memory for the time of past events. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, M.S. The role of temporal landmarks in autobiographical memory processes. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, T.; Bluck, S. Getting a life: The emergence of the life story in adolescence. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 748–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. The psychology of life stories. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, D.K. Autobiographical periods: A review and central components of a theory. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2015, 19, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Mortality Analysis. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality. (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Gu, X.; Tse, C.; Brown, N.R. Factors that modulate the intergenerational transmission of autobiographical memory from older to younger generations. Memory 2020, 28, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, D.K.; Jensen, T.; Holm, T.; Olesen, M.H.; Schnieber, A.; Tønnesvang, J. A 3.5 year diary study: Remembering and life story importance are predicted by different event characteristics. Conscious. Cogn. 2015, 36, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomsen, D.K.; Berntsen, D. The cultural life script and life story chapters contribute to the reminiscence bump. Memory 2008, 16, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, M.A.; Mehl, M.R.; Pennebaker, J.W. Linguistic markers of psychological change surrounding September 11, 2001. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirst, W.; Echterhoff, G. Remembering in conversations: The social sharing and reshaping of memories. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.A. First Experience Memories: Contexts and Functions in Personal Histories. In Theoretical Perspectives on Autobiographical Memory; Conway, M.A., Rubin, D.C., Spinnler, H., Wagenaar, W.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.C.; Rahhal, T.A.; Poon, L.W. Things learned in early adulthood are remembered best. Mem. Cognit. 1998, 26, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, D.K. There is more to life stories than memories. Memory 2009, 17, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, U.; Theorell, T.; Lind, E. Life changes and myocardial infarction: Individual differences in life change scaling. J. Psychosom. Res. 1975, 19, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, E.E.; Presskreischer, R.; Han, H.; Barry, C.L. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA 2020, 324, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandifar, A.; Badrfam, R. Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 51, 101990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torales, J.; O’Higgins, M.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Ventriglio, A. The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crayne, M.P. The traumatic impact of job loss and job search in the aftermath of COVID-19. Psychol. Trauma. 2020, 12, S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purtle, J. COVID-19 and mental health equity in the United States. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2020, 55, 969–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killgore, W.D.; Cloonan, S.A.; Taylor, E.C.; Dailey, N.S. Mental health during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 561898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, K. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid. Based Dent. 2006, 7, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).