Abstract

Widespread environmental contamination by perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) is raising particular concerns. PFAS are remarkably resistant to microbial degradation and have a profound impact on the structure and function of microbial communities. In this study, we analyzed the effect of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) on bacterial quorum sensing, a communication process that in marine Vibrio species regulates biofilm formation and dissolution, virulence factors, swimming/swarming motility and bioluminescence. A system to continuously monitor bioluminescence during the growth on agar medium of Vibrio campbellii BB120 and isogenic luxS-, cpsA- and luxM-defective mutants, unable to synthesize, respectively, the autoinducers AI-2, CAI-1, and HAI-1, was utilized. By this system, we found that PFOA has dramatic effects on bacterial growth on agar and light emission kinetics, with specific effects in the different strains depending on the set of the autoinducers produced. Furthermore, we found that PFOA inhibited swarming motility in cqsA- and luxM-defective mutants which exhibited a very robust swarming phenotype in the absence of PFOA due to the lack of CAI-1 or HAI-1 that inhibit motility. The inhibitory effect on motility could be due to increased adherence of bacterial colonies to the agar substrate caused by the presence of PFOA. These results, although obtained in an in vitro system, suggest that PFOA may strongly interfere with bacterial growth kinetics and quorum sensing-regulated responses.

1. Introduction

Among the myriad of human-made chemical pollutants, perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) raise deep concerns. PFAS comprise a large group of compounds that have an alkyl chain backbone, typically 4 to 16 carbon atoms in length, and a functional moiety (primarily carboxylate, sulfonate, or phosphonate). PFAS were introduced as ideal surfactants into numerous industrial processes in the second half of the 20th century, with applications in the manufacturing of hundreds of consumer products and industrial processes [1,2,3]. Among them, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA, C8HF15O2) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS, C8HF17OS3) are the most well-known representatives.

As environmental contaminants with global distribution and extreme persistence, PFAS pose a One Health challenge impacting microbial, animal, and human health. Their chemical stability is due to the strong carbon–fluorine bonds, which are rarely degraded in natural systems. This has led to widespread environmental and biological accumulation and, over the past two decades, growing evidence of adverse health and ecological effects [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. From terrestrial environments, where their production, use, and disposal occur, PFAS are transported through waterways, runoff and atmospheric deposition into the ocean, which serves as the primary global sink for PFAS [14,15]. Reported concentrations in seawater and marine sediments vary greatly depending on the geographic area and sampling site. Region-specific differences also exist in PFAS profiles [14,15]. On a global scale, PFOA, followed by PFOS, is the most abundant PFAS in marine waters, with average concentrations ranging from approximately 0.2 to 2 ng/L in minimally impacted areas, but with values that can reach almost 100 ng/L in moderately impacted areas, and 20,000 ng/L in highly impacted estuaries [14,15], such as that of the Xiaoqing River in China [16]. PFOA is also abundant in marine sediments, with average concentrations ranging from approximately 0.15 to 0.7 ng/g dry weight (dw), but with values that can exceed 2 ng/g dw [15]. PFOA is also the predominant PFAS in marine phytoplankton and in marine invertebrates, with a median PFOA/PFOS ratio 50 times higher in invertebrates than in fish [14,15,17]. Notably, PFOA is found to bioaccumulate in marine organisms, including phytoplankton, such as Chlorella, one of the dominant green algae in the ocean, showing a bioconcentration factor (BCF) of about 100 with PFOA concentration about 20 mg/L [18]. Bioaccumulation of PFOA in marine organisms is greatest in animals higher up the food chain, implying that PFOA concentrations in marine organisms can exceed those found in marine sediments by 100 (for invertebrates) and 1000 (for fish) [17,19].

In response to this evidence, PFAS have been subjected to increasingly stringent global regulations. In Europe, the production and use of PFOA are now banned under Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 on persistent organic pollutants, as amended by Regulation (EU) 2020/784. These regulations stipulate that PFOA and its salts may only be present as an unintentional trace contaminant (UTC), defined as a residual impurity not intentionally added and present at concentrations below specific thresholds (≤0.025 mg/kg for PFOA and ≤1 mg/kg for PFOA-related compounds). While temporary exemptions remain in place for limited industrial applications (e.g., in firefighting foams), they are scheduled to expire by December 2025. Similarly, the allowed thresholds for PFOS are being aligned with those of PFOA. Despite these regulatory efforts, contamination remains widespread: a recent investigation combining expert-reviewed journalism with scientific validation mapped over 23,000 confirmed and suspected PFAS contamination sites across Europe [20].

Both PFOA and PFOS are harmful to marine life by damaging cell membranes, causing oxidative stress, and affecting animal growth and reproduction, but PFOS is generally considered more toxic and bioaccumulative in the aquatic environment than PFOA, resulting in greater health effects on organisms and higher concentrations in food chains [21,22]. In fact, despite having the same number of carbon atoms, PFOS shows greater hydrophobicity than PFOA due to two important structural differences: (i) it has an additional CF2 unit; (ii) it has a sulfonate group which, being a relatively hard base, adsorbs easily on oxide surfaces, much more than the carboxylate group in PFOA [23]. In contrast, PFOA is more mobile than PFOS, and its surface activity can lead to its adsorption at the air-water interface, which influences its mobility pattern in aquatic environments and its cycling between water, sediments, and marine life forms [23]. This makes PFOA particularly interesting for studying the impact of PFAS on marine ecosystems. Additionally, one study found that PFOA is more toxic than PFOS to some aquatic organisms, suggesting potential differences in how they affect different species [24].

PFAS are remarkably resistant to microbial degradation [25] because they contain high-energy carbon–fluorine bonds that occur very rarely in microbial chemistry and the end product of biodegradation, fluorine, can be very toxic to microorganisms [26]. As a result, PFAS profoundly affect also the structure and function of microbial communities [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. In particular, prolonged exposure to PFAS in soils, sediments and vadose regions leads to a marked reduction in biodiversity and an enrichment of specific bacterial phyla, particularly Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria and Actinobacteria, which exhibit greater intrinsic resistance to PFAS than other phyla [27,31,34]. Furthermore, PFAS are potential environmental factors that promote antimicrobial resistance [35]. These findings have raised particular concerns since microbial communities are crucial in the balance of biogeochemical cycles, in the decomposition of pollutants, in chemical transformation, in the food chain.

Among microbial regulatory systems, quorum sensing is a central mechanism that allows bacteria to coordinate gene expression in response to population density [36]. Quorum sensing governs essential bacterial behaviors such as biofilm formation, virulence, and motility. In marine Vibrio species—particularly those within the Harveyi clade (which includes V. campbellii, V. harveyi, and related species)—quorum sensing also controls bioluminescence, a trait that facilitates both environmental adaptation and host interactions [37,38,39]. These Vibrio species can exist as planktonic organisms, symbionts, or pathogens, depending on environmental conditions and quorum-regulated gene expression [40,41,42]. In particular, V. campbellii integrates three autoinducer signals—HAI-1, CAI-1, and AI-2—through a well-characterized phosphorelay system that converges on the LuxR master regulator. This regulatory cascade governs the lux operon, controlling light emission, and plays key roles in the modulation of collective behaviors such as swarming motility and colony morphology [43,44].

While the effects of PFAS on microbial diversity and physiology have been increasingly investigated, their potential to interfere with quorum sensing systems remains poorly understood. PFAS, such as PFOA, could influence quorum sensing systems through multiple mechanisms, such as: (i) an increase in bacterial membrane permeability, which may enhance the diffusion of the autoinducers and/or may amplify the quorum sensing response, as observed in studies with Aliivibrio fischeri, a marine bacterium harboring a quorum sensing system based on a single autoinducer, AHL, belonging to the acyl homoserine lactone family [45]; (ii) a direct interference with quorum sensing pathways, such as the production or reception of the autoinducers; (iii) an indirect effect of the expression of quorum sensing-regulated genes caused by altered membrane permeability and/or the induction of oxidative stress. In principle, it is also possible that, in bacteria with multiple quorum-sensing systems controlled by different types of autoinducers, PFOA may have opposing effects, depending on the signaling molecules produced and the mechanisms of signal reception.

Therefore, in this study, we explored the effects of PFOA on quorum sensing-dependent traits, including bioluminescence, motility, and colony architecture, using V. campbellii strain BB120, a bacterium with multiple quorum-sensing systems. V. campbelli is ubiquitous in marine environments, including marine, estuarine, and coastal waters. Its hosts include penaeid shrimp, various fish species, and mollusks [46]. To analyze the specific effects of PFOA on the different autoinducers, in addition to V. campbellii BB120, we also used isogenic mutants defective in the production of the autoinducers AI-2 (luxS), CAI-1 (cqsA), and HAI-1 (luxM). Furthermore, we built an experimental setup to continuously evaluate bioluminescence during bacterial growth on agar plates, because under these conditions we were able to analyze other quorum sensing-dependent traits, such as swarming motility, whereas bioluminescence is usually monitored during the growth of bacteria in broth [44,47,48]. Moreover, growth on solid media, rather than liquid media, better simulates the conditions in which V. campbellii interacts with its animal hosts, colonizing their surfaces. The concentration of PFOA chosen in this study to best highlight the effects of PFOA on V. campbellii, i.e., half the minimal inhibitory concentration, is high but not far from that achievable on marine animals in environments heavily contaminated by PFOA, given their ability to bioaccumulate this compound.

Our aim is to evaluate whether PFOA affects V. campbellii colony growth and architecture, bioluminescence, swarming motility, and virulence gene expression and, if so, to seek to understand the underlying mechanisms by analyzing the quorum sensing signaling cascade.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains, Growth Conditions, and RT-qPCR

Harveyi clade Vibrio strain BB120 (wild type) and isogenic derivatives KM387 (ΔluxS), JMH603 (cqsA::Cmr) and JAF633 (ΔluxM linked to Kanr) [37,38] were kindly provided by prof. Bonnie L. Bassler (Princeton University, USA). Vibrio strain BB120 (also known as ATCC BAA-1116), which was originally classified as V. harveyi, was then proved to be V. campbellii by microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization [49]. Vibrio strains were cultivated in nutrient broth [BD DifcoTM BactoTM, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA] containing 3% NaCl [Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA]. Agar [BD DifcoTM BactoTM, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA] was added to this broth at a final concentration of 1.5% to formulate luminescence agar (LA). When necessary, the following antibiotics were added to maintain strain selection: chloramphenicol (25 µg/mL), kanamycin (50 µg/mL).

For bioluminescence monitoring strains were pre-cultured in nutrient broth containing 3% NaCl at 24 °C under shaken (250 rpm) up to an optical density (O.D.) of 1.0 at 600 nm. A total of 10 µL of bacterial suspensions were spotted at the center of standard polystyrene Petri dishes (diameter 50 mm) containing LA supplemented with PFOA [Sigma-Aldrich] dissolved in isopropanol [Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA] (final PFOA concentration = 0.156 mg/mL; final isopropanol concentration = 0.078% isopropanol) (LA-PFOA), or control LA (LA-CTL) containing 0.078% isopropanol, and incubated at 24 °C.

Bacterial biomass of colonies growing on LA-PFOA or LA-CTL agar plates was determined by O.D. measurement. To this purpose, the bacteria were collected at different time intervals and resuspended in 1 mL of Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The O.D. of the bacterial suspensions was measured at a wavelength of 600 nm of the incident light. The samples were diluted to fall within the linear range of the optical system, and the O.D. data were corrected by the dilution factor used for the O.D. measurement.

After 120 h of growth, three LA-CTL or LA-PFOA plates containing V. campbellii BB120 were used to collect bacterial biomass with a sterile loop. The collected cells were immediately suspended in ice-cold saline (0.9% NaCl). The suspension was vortexed at maximum speed for 10 s and then returned to ice for 30 s. This vortex–ice cycle was repeated three times. RNA extraction and other molecular procedures were carried out as previously reported [35,50]. RT-qPCR was performed using previously described primers targeting the luxA, luxR, and hfq genes [51].

2.2. Bioluminescence Monitoring

To perform bacterial luminescence measurements, we prepared two identical experimental configurations inserted inside the climatic chamber under almost constant temperature and humidity conditions, as previously described [51]. Absolute darkness was maintained inside. Each experimental setup contained a very sensitive Hamamatsu1P28 photomultiplier (PMT), capable of recording the low-intensity light emitted by our samples. In fact, the gain factor, a characteristic of the photomultiplier, was about 5 × 106. When photons strike the cathode, electrons are emitted and then accelerated and multiplied by the dynodes. As a result, the anode produces approximately 5 × 106 electrons for each electron generated, allowing for the detection of very weak light signals. The nominal spectral sensitivity of the photomultiplier ranged from 185 to 650 nm. Its active window, which we used to collect the light emitted by the samples, was 24 mm high and 8 mm wide. Furthermore, the bacterial spot was positioned at a distance of 30 mm from the PMT window, allowing us to collect a large share of the photons emitted in the solid angle between the sample and the PMT. To better evaluate the performance of the strains by analyzing colony growth and bioluminescence, we assumed an initial linear emission phase corresponding to the growth trend. Over time, a secondary phase characterized by reduced emission (extinction coefficient) was associated with the slowdown of bacterial growth and subsequent cell death. This behavior was therefore modeled using an exponential function. The photomultiplier signals were sent to a Pasco Science Workshop 750 Interface CI-7500 workstation [Pasco, Roseville, CA, USA], interfaced to a personal computer used both as a storage device and to time the measurements. One channel of the workstation was also used to record the temperature of the climatic chamber during the entire experiment by a semiconductor sensor.

For each strain, both wild-type and mutant, we performed two types of experiments: continuous monitoring and parallel measurements. Continuous monitoring experiments were performed first, with each strain observed until light emission ceased. Subsequently, light output was measured in parallel experiments, in which multiple colonies were grown simultaneously and bioluminescence was recorded at defined time intervals.

2.3. Contact Angle Determination

The experimental setup consists of a Redlake Imaging Motion Analyzer [Redlake Imaging Corporation, Morgan Hill, CA, USA], a linear micrometer positioner with integrated tilt table, a backlit led diffuser, and a module dispenser of low volume droplet. Measurements were performed by depositing a drop ~2.0 µL of distilled water. Droplet deposition was recorded from the transient phase to the steady-state configuration, where the static contact angle was measured. Five measurements of contact angle were performed for each sample by using “Drop Shape Analysis” plugin of ImageJ software (1.51 23). Similarly, the contact angle between V. campbelli colonies and the agar surface was determined after 72 h of growth. Measurements were performed on 5 different colonies for each strain and each condition used in this study.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical comparisons between control and PFOA-treated samples were performed using a two-sample Student’s t-test (Welch correction for unequal variances) implemented in Python 3.12.12 (SciPy 1.16.3 library). Boxplots were generated using the Pandas 2.2.2 and Matplotlib 3.10.0 packages.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of PFOA on the Bioluminescence of Wild Type V. campbellii BB120

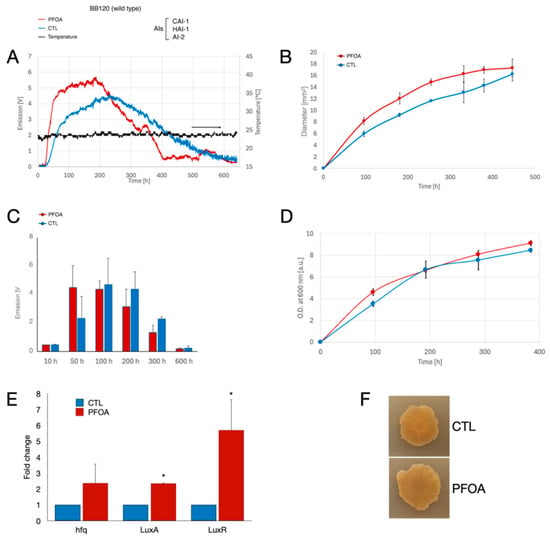

We conducted a preliminary experiment to continuously monitor the bioluminescence produced by Vibrio campbellii BB120 (Figure 1A). We then confirmed the trend in light emission by repeating the growth experiment three times and measuring the bioluminescence at fixed time points (Figure 1C). During the continuous monitoring, we found that in LA-CTL plates, the luminescence of V. campbellii BB120 increased progressively during the first 80 h and more slowly during the subsequent 150 h, reaching a plateau at approximately 230 h (Figure 1A). After this time, the luminescence slowly decreased until it was no longer detectable after about 600 h. Compared to LA-CTL plates, the luminescence of V. campbellii BB120 increased much more rapidly in LA-PFOA plates, especially during the first 50 h, reaching a plateau at approximately 180 h. After this time, the luminescence decreased more rapidly than in control plates, until it was no longer detectable after about 400 h. Thus, at later time points (250 to 600 h), bacteria grown on plates containing PFOA emitted considerably less light than control plates. This pattern of bioluminescence development during growth on LA-CTL or LA-PFOA was also confirmed in independent experiments, in which luminescence was measured at fixed time points (Figure 1C). In all experiments, we observed a more pronounced luminescence during the early stages of growth on LA-PFOA compared to LA-CTL (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Effects of PFOA on colony growth and bioluminescence of V. campbellii BB120 grown on agarized medium. (A) Ten µL of a bacterial suspension of V. campbellii BB120 (with an O.D. at 600 nm = 1.0) were inoculated in the center of polystyrene Petri dishes containing LA-PFOA agar plates (red) or control LA-CTL agar plates (blue). Continuous light emission was monitored for 600 h. (B,C) The light emission monitoring experiment was repeated three times, and the light emission (B) and colony size (diameter, mm) (C) were measured at fixed time points. (D) Ten µL of a bacterial suspension of V. campbellii BB120 (with an O.D. at 600 nm = 1.0) were inoculated in the center of polystyrene Petri dishes containing either LA-PFOA agar plates (red) or control LA-CTL agar plates (blue), and colonies were collected at different time points for biomass assessment. Two plates were analyzed at each time point. (E) During growth, bacterial biomass samples were sampled at 120 h and used to perform RT-qPCR of three quorum-sensing-related genes: luxR, luxA, and hfq. (F) Colonies of V. campbellii BB120 grown on LA-PFOA (lower panel) or LA-CTL agar plates (upper panel) at the end of growth. (* p-value < 0.05).

We then wondered whether the stimulation of bioluminescence in the early growth phase was due to an effect of PFOA on bacterial growth, as we noticed a slightly larger colony area on LA-PFOA plates than on LA-CTL plates during the time course of the experiment (Figure 1B,F and Figure 2A). Therefore, we collected the colonies of the bacteria grown on LA-PFOA plates than on LA-CTL plates at different times of growth and, after resuspending them in saline, measured both biomass by spectrophotometric method (O.D. 600 nm) and total protein concentration (Figure 1D). Colony size (diameter) was closely correlated with colony biomass (R2₍PFOA₎ > 0.99; R2₍CTL₎ > 0.98), as demonstrated for Vibrio campbellii BB120 grown on LA-PFOA (Figure S1A) or LA-CTL (Figure S1B). The results showed that, indeed, PFOA increased bacterial growth rates during the initial phase of colony growth up to about 100 h, but after this time growth rates decreased compared with the control reaching a similar value at the end of the growth (Figure 1F). As a result, the final biomass of the bacteria grown on the LA-PFOA plates and the LA-CTL plates was similar. This result indicates that the stimulatory effect of PFOA on bioluminescence in the early phase of colony growth could be due to a stimulatory effect of PFOA on bacterial growth.

Figure 2.

Effects of PFOA on colony growth pattern and contact angle of V. campbellii BB120 grown on agarized medium. (A) Colonies of V. campbellii BB120 grown on LA-PFOA or LA-CTL agar plates. (B,C) Contact angle of distilled water drops (B) or colonies of V. campbellii BB120 (C) on LA-PFOA or LA-CTL agar plates. Blu lines (B) represent the tangents to the liquid profile at the point of contact with the surface. (D) Average values of contact angles of colonies of V. campbellii BB120 grown on LA-PFOA or LA-CTL agar plates (* p-value < 0.05). The blue box represents the interquartile range (middle 50% of values), the red line is the median, and the gray whiskers indicate the data spread.

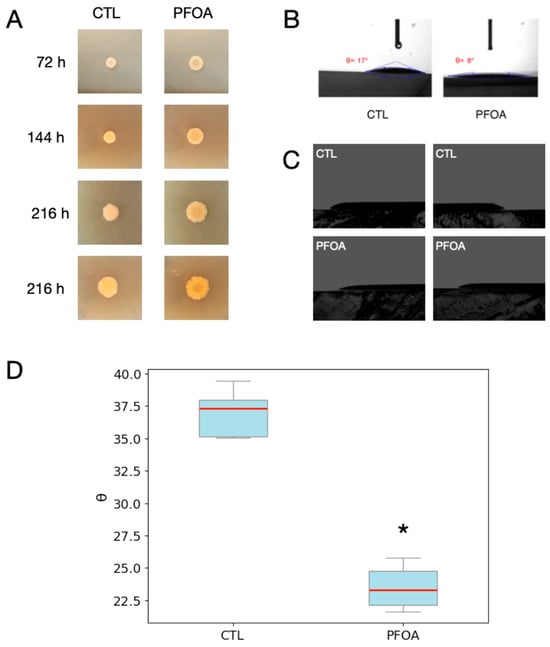

Furthermore, we observed that the bacteria on the PFOA-containing agar plates formed flatter colonies than those on the control agar plates (Figure 2A,C). Therefore, we measured the contact angles using a drop of water (Figure 2B) or the bacterial colonies (Figure 2A,C,D). Indeed, we found that the water droplets on the LA-PFOA plates formed a smaller contact angle (θ = 8°) than those on the LA-CTL plates (θ = 17°) (Figure 2B) and that the colonies on the LA-PFOA (Figure 2A) plates formed a smaller contact angle (θ = 22°) than those on the LA-CTL plates (θ = 38°) (Figure 2C,D). This finding suggests that the presence of PFOA may increase bacterial adherence to the agar surface, thereby affecting bacterial access to media components, bacterial motility, biofilm formation, and colony architecture. As a result, the dynamics of bacterial growth were affected by the presence of PFOA.

Finally, we investigated whether the luminescence enhancement observed in bacteria grown on LA-PFOA was due to stimulation of the quorum-sensing regulatory circuit. To this end, we performed RT-qPCR analysis (Figure 1F) sampling the bacterial biomass at 120 h of growth. RTqPCR revealed that PFOA increased the transcriptional level of luxR, the main transcriptional regulator involved in quorum-sensing activation. Similarly, we detected higher transcriptional levels of luxA, which encodes luciferase, and hfq, which post-transcriptionally regulates several non-coding RNAs associated with quorum-sensing regulation (Figure 1F). These data are consistent with the observed increase in colony size and, consequently, with earlier activation of quorum sensing when the bacteria were grown on LA-PFOA.

3.2. Analysis of Bioluminescence Emission Curves of Wild-Type V. campbellii BB120

In an attempt to simplify this complex scheme, we tried to fit the light emission curves of bacteria growing on agar plates by representing them as the result of the action of two components. Indeed, looking at the light emission curves, we can observe that they can be considered as composed of two factors, both of which are time-dependent: the first factor represents the light emission associated with colony growth, which we can image increasing, ; the second factor represents the contribution of the reduction in the emission (or extinction coefficient), associated with bacterial growth arrest and death (modulation factor), . A and B represent the corresponding intensity; represents the delay time; is the time constant, or decay time, and is the time. The expression of the total emission is governed by the following expression:

In conclusion, the total emission is the theoretical expression of the emission due to the product of the two factors, the linear and exponential components, as described below.

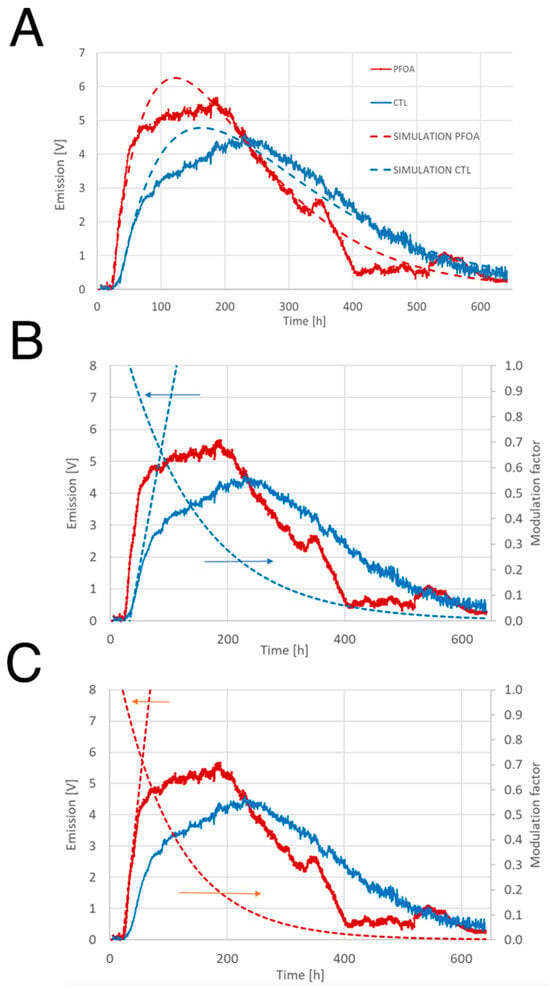

The values of the parameters are inserted in Table 1. Simulations are shown in Figure 3. It can be seen that when bacteria were grown on LA-PFOA agar plates (Figure 3A,C), the angular coefficient, or slope, of the first factor (linear), was higher (0.17 V/h) than that measured with bacteria grown on LA-CTL agar plates (0.10 V/h) (Figure 3A,B), indicating a positive effect of PFOA on induction of bioluminescence. The slope of the first factor, in fact, reflects the rates of biomass increase in the early stages of colony growth (during the first 50 h) (Figure 1D). However, the second factor (exponential), which regulates light emission abatement, seems to have a more pronounced effect precisely on bacteria growing on LA-PFOA, abating light emission substantially after 100 h, compared with those growing on LA-CTL, in which light emission begins to abate after 130 h.

Table 1.

Simulation results of the emission light by Equation (1).

Figure 3.

Real and simulated light emission curves of V. campbellii BB120. (A) Comparison of real and simulated light emission curves. The simulated curves were calculated according to Equation (1) and are shown as dashed lines. (B,C) Comparison of real and simulated curves (dashed lines) showing the linear and exponential components derived from Equation (1) for growth in LA-CTL (B) and LA-PFOA (C). The orange and blue arrows indicate the value scale (y-axis) to which the dashed curves refer.

The result of the simulations of bioluminescence curves is consistent with the effect of PFOA on growth dynamics. As shown, PFOA stimulates the bacterial growth (and, hence, bioluminescence induction), but also the premature entry into the stationary phase (and, hence, bioluminescence abatement). However, as bioluminescence is controlled by different AIs whose production is time-regulated during the growth of V. campbellii BB120 [44], we could exclude that the effect of PFOA on bioluminescence curves could be due to distinct effects of PFOA on the different AIs. Therefore, the next step was to analyze mutants unable to produce each of the three AIs.

3.3. Effects of PFOA on the Bioluminescence of V. campbellii Quorum-Sensing Mutants

To gain more insight about the molecular mechanisms involved in the stimulation of bioluminescence by PFOA at early growth time points, three derivative mutants of V. campbellii BB120 were used: KM387 (ΔluxS), JMH603 (cqsA::Cmr), and JAF633 (ΔluxM linked to Kanr), unable to synthesize AI-2, CAI-1, and HAI-1, respectively. As in the case of Vibrio campbellii BB120, bioluminescence during growth was first monitored continuously and then measured at defined time points to confirm the observed patterns.

We observed distinct patterns in the different mutants and a different effect of PFOA:

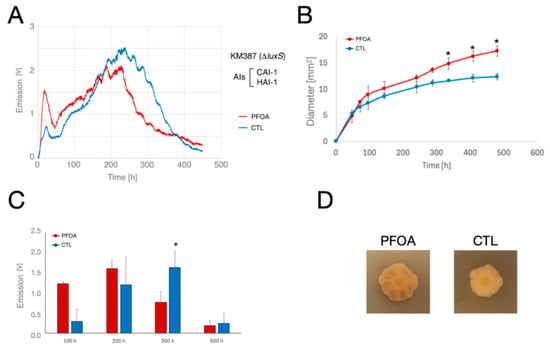

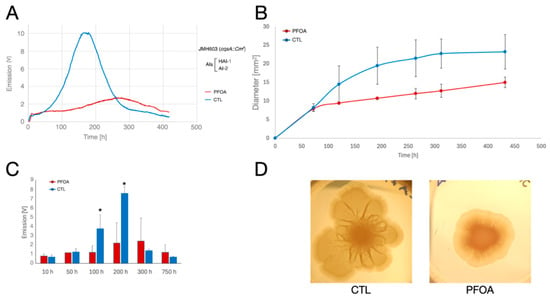

- V. campbellii KM387 (ΔluxS; AIs produced: CAI-1 and HAI-1) (Figure 4A,C). During the continuous monitoring, in both LA-CTL and LA-PFOA plates, we observed a similar pattern consisting of two distinct peaks of light emission. The first peak culminated after about 20 h and increased more rapidly, reaching a higher plateau in LA-PFOA plates than in LA-CTL plates (Figure 4A). In contrast, the second peak reached a higher plateau (at about 230 h) in LA-CTL plates than in LA-PFOA plates (at about 190 h). In addition, just as in V. campbellii BB120, luminescence decreased more rapidly in LA-PFOA plates than in LA-CTL plates, but with a different trend in the final part. The observed patterns were also confirmed in parallel experiments, which showed that the bioluminescence of Vibrio campbellii KM387 was stimulated by PFOA during the initial stages of growth (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Effects of PFOA on colony growth and bioluminescence of V. campbellii KM387 mutant grown on agarized medium. (A,B) Ten µL of bacterial suspensions (with an O.D. at 600 nm = 1.0) of V. campbellii KM387 mutant, defective in AI-2 production, were inoculated in the center of polystyrene Petri dishes containing LA-PFOA agar plates (red) or control LA-CTL agar plates (blue). Continuous light emission was monitored for about 500 h. (B,C) The light emission monitoring experiment was repeated three times, and the light emission (B) and colony size (diameter, mm) (C) were measured at fixed time points. (D) Colonies of V. campbellii KM387 grown on LA-PFOA agar plates or control LA-CTL agar plates for 500 h. * p-value < 0.05.

Figure 4. Effects of PFOA on colony growth and bioluminescence of V. campbellii KM387 mutant grown on agarized medium. (A,B) Ten µL of bacterial suspensions (with an O.D. at 600 nm = 1.0) of V. campbellii KM387 mutant, defective in AI-2 production, were inoculated in the center of polystyrene Petri dishes containing LA-PFOA agar plates (red) or control LA-CTL agar plates (blue). Continuous light emission was monitored for about 500 h. (B,C) The light emission monitoring experiment was repeated three times, and the light emission (B) and colony size (diameter, mm) (C) were measured at fixed time points. (D) Colonies of V. campbellii KM387 grown on LA-PFOA agar plates or control LA-CTL agar plates for 500 h. * p-value < 0.05.

The first peak of light emission was correlated with growth. Compared to LA-CTL plates, this peak was higher in the LA-PFOA plates, where PFOA stimulated bacterial colony size at early time points (Figure 4B,D). In contrast, the second bioluminescence peak was lower in the LA-PFOA plates than in the LA-CTL plates (Figure 4A), despite the larger colony size (Figure 4B). This finding suggests an inhibition of PFOA on light emission at later time points, the possible cause of which is discussed below.

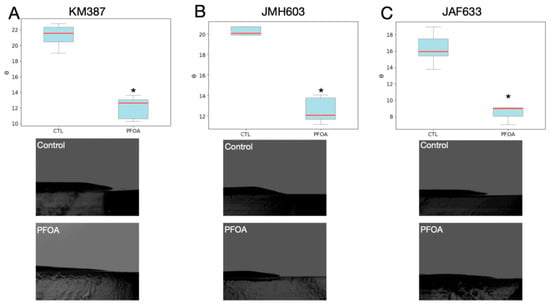

After 72 h of growth, Vibrio campbellii KM387 produced a smaller contact angle on the LA-CTL surface (Figure 5A) than V. campbellii BB120 (Figure 2C,D); however, this strain also exhibited a decreased contact angle when grown on LA-PFOA.

Figure 5.

Effects of PFOA on contact angles measured for each mutant strain on LA-CTL or LC-PFOA. (A) V. campbellii KM387. (B) V. campbellii JMH603. (C) V. campbellii JAF633. * p-value < 0.05. The blue box represents the interquartile range (middle 50% of values), the red line is the median, and the gray whiskers indicate the data spread.

- V. campbellii JMH603 (cqsA::Cmr; AIs produced: AI-2 and HAI-1) (Figure 6). During the continuous monitoring of the bioluminescence, we observed an initial peak of light emission that culminated after about 10 h, without substantial differences between LA-CTL and LA-PFOA plates. Only in LA-CTL plates, a very regular bell-shaped and high emission curve started after about 50 h, culminated after 170 h, and ended after about 300 h of growth. At the peak, the light emission curve with this mutant reached higher values (>2-fold) than those reached with the wild type strain (Figure 6A). In contrast, in the LA-PFOA plates, after the initial peak, we observed a slower and more restrained increase in the light emission curve that culminated at about 275 h and then decreased just as slowly. The observed patterns were also confirmed in parallel experiments (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Effects of PFOA on colony growth and bioluminescence of V. campbellii JMH603 mutant grown on agarized medium. (A) Ten µL of bacterial suspensions (with an O.D. at 600 nm = 1.0) of V. campbellii JMH603 mutant, defective in CAI-1 production, were inoculated in the center of polystyrene Petri dishes containing LA-PFOA agar plates (red) or control LA-CTL agar plates (blue). Continuous light emission was monitored for about 500 h. (B,C) The light emission monitoring experiment was repeated three times, and the light emission (B) and colony size (diameter, mm) (C) were measured at fixed time points. (D) Colonies of V. campbellii JMH603 grown on LA-PFOA agar plates (right) or control LA-CTL agar plates (left) for 530 h. * p-value < 0.05.

Figure 6. Effects of PFOA on colony growth and bioluminescence of V. campbellii JMH603 mutant grown on agarized medium. (A) Ten µL of bacterial suspensions (with an O.D. at 600 nm = 1.0) of V. campbellii JMH603 mutant, defective in CAI-1 production, were inoculated in the center of polystyrene Petri dishes containing LA-PFOA agar plates (red) or control LA-CTL agar plates (blue). Continuous light emission was monitored for about 500 h. (B,C) The light emission monitoring experiment was repeated three times, and the light emission (B) and colony size (diameter, mm) (C) were measured at fixed time points. (D) Colonies of V. campbellii JMH603 grown on LA-PFOA agar plates (right) or control LA-CTL agar plates (left) for 530 h. * p-value < 0.05.

During the experiments, we noticed that the colonies formed on LA-CTL plates by the JMH603 mutant showed a marked tendency to spread on the agar surface (Figure 6B,D). This behavior, which did not allow for modeling the emission curve, as was performed with V. campbellii BB120 (Figure 3), is caused by swarming motility, a collective movement mode in which bacteria rapidly migrate and grow across surfaces, forming dynamic patterns of vortices and jets [52,53,54,55]. Therefore, the high-light emission curve that began after about 50 h was produced by the bacteria swarming at the colony margins on LA-CTL plates. In fact, this late light emission was much more reduced and delayed on LA-PFOA plates, where bacterial swarming was inhibited (Figure 6B,D). Therefore, as well as in V. campbellii BB120 and in V. campbellii KM387, the curves of light emission were correlated with growth dynamics: in LA-CTL plates, the high light emission curve began in conjunction with a net increase in colony size at about 50 h due to the bacterial swarming, which did not occur in LA-PFOA plates (Figure 6B,D).

After 72 h of growth, V. campbellii JMH603 produced a contact angle on the LA-CTL surface (Figure 5B) smaller than that of V. campbellii BB120 (Figure 2C,D) but comparable to that of V. campbellii KM387 (Figure 5A). This strain also showed a reduced contact angle when grown on LA-PFOA.

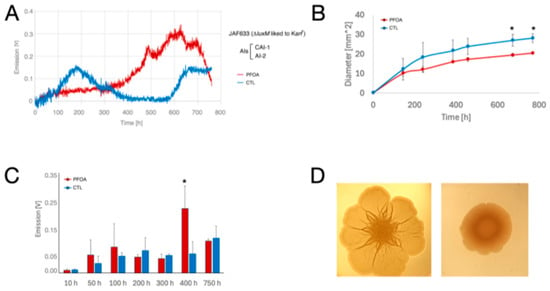

- V. campbellii JAF633 (ΔluxM linked to Kanr; AIs produced: AI-2 and CAI-1) (Figure 7). This mutant emits light very weakly. During the continuous monitoring of the bioluminescence, the bacteria emitted a weak first light wave culminating at about 175 h in LA CTL plates (Figure 7A). This wave was barely detectable in LA-PFOA plates, where the bacteria started to increase the light emission at about 400 h (Figure 7A), in conjunction with an increase in colony size (Figure 7B). Furthermore, a late light wave appeared in LA-CTL plates at about 600 h in conjunction with a marked increase in colony size (Figure 7B,D). Thus, also with this mutant, the peaks of light emission were correlated with growth dynamics, and like JMH603, JAF633 showed a marked tendency to swarm on LA-CTL plates (Figure 7B,D), and swarming was inhibited on LA-PFOA plates. Additionally, for this mutant, the observed light emission patterns were confirmed in parallel experiments (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. Effects of PFOA on colony growth and bioluminescence of V. campbellii JAF633 mutant grown on agarized medium. (A) Ten µL of bacterial suspensions (with an O.D. at 600 nm = 1.0) of V. campbellii JAF633 mutant, defective in HAI-1 production, were inoculated in the center of polystyrene Petri dishes containing LA-PFOA agar plates (red) or control LA-CTL agar plates (blue). Continuous light emission * p-value < 0.05.was monitored for about 750 h. (B,C) The light emission monitoring experiment was repeated three times, and the light emission (B) and colony size (diameter, mm) (C) were measured at fixed time points. (D) Colonies of V. campbellii JAF633 grown on LA-PFOA agar plates (right) or control LA-CTL agar plates (left) for 380 h. * p-value < 0.05.

Figure 7. Effects of PFOA on colony growth and bioluminescence of V. campbellii JAF633 mutant grown on agarized medium. (A) Ten µL of bacterial suspensions (with an O.D. at 600 nm = 1.0) of V. campbellii JAF633 mutant, defective in HAI-1 production, were inoculated in the center of polystyrene Petri dishes containing LA-PFOA agar plates (red) or control LA-CTL agar plates (blue). Continuous light emission * p-value < 0.05.was monitored for about 750 h. (B,C) The light emission monitoring experiment was repeated three times, and the light emission (B) and colony size (diameter, mm) (C) were measured at fixed time points. (D) Colonies of V. campbellii JAF633 grown on LA-PFOA agar plates (right) or control LA-CTL agar plates (left) for 380 h. * p-value < 0.05.

After 72 h of growth, V. campbellii JAF633 produced a contact angle on the LA-CTL surface (Figure 5C) smaller than that of V. campbellii BB120 (Figure 2C,D) and smaller than those of V. campbellii KM387 (Figure 5A) and V. campbellii JMH603(Figure 5B). Even for this strain, the contact angle decreased when grown on LA-PFOA.

4. Discussion

4.1. PFOA Affects Growth and Light Emission Kinetics of V. campbellii on Agar

In this study we found that the addition of PFOA to agar medium has dramatic effects on growth on agar and light emission kinetics of V. campbellii BB120 and three AI-defective isogenic mutants KM387, JMH603 and JAF633, unable to produce, respectively, AI-2, CAI-1, and HAI-1. In an in vitro system with bacteria growing at 24 °C on agar medium and bioluminescence continuously monitored, we found that PFOA stimulated the induction of bioluminescence emitted at early growth time points by wild type V. campbellii BB120 and KM387 mutant (AI-2-defective) (Figure 1A and Figure 4A).

We initially thought that our results might be consistent with a previous study showing that PFAS exposure increases the quorum-sensing response of A. fischeri by enhancing the effect of its AI, AHL, belonging to the acyl homoserine lactone family [45]. In this study, the authors demonstrate that A. fischeri cultures exposed to PFAS were brighter than control cultures after receiving the AHL. Additionally, bacteria exposed to PFAS were also more permeable to a semipermeable membrane dye. This led to the conclusion that the increased permeability to AHL was, at least in part, the cause of the increased luminescence that can be initiated prematurely at lower bacterial densities than control conditions [45].

Although it is plausible that a similar mechanism may be involved in the stimulation of the onset of bioluminescence in V. campbellii BB120 and KM387, because both the strains are capable of producing HAI-1, an AI of the acyl homoserine lactone family, we did not observe the same effect with the JMH603 mutant (CAI-defective), which is also capable of producing HAI-1 (Figure 6A). Furthermore, in the KM387 mutant, we observed a pattern consisting of two light peaks, possibly determined by the sequential action of HAI-1 and then CAI-1, consistent with previous results showing that CAI-1 is produced later than HAI-1 during the growth of V. campbellii [44]. The first light peak was stimulated by PFOA, the second was inhibited (Figure 4A), suggesting a possible inhibitory effect of PFOA on CAI-stimulated bioluminescence.

4.2. PFOA Affects the Growth Dynamics by Increasing Bacterial Adhesion to the Substrate

Complementing these findings, our mechanistic investigations reveal that PFOA alters substrate properties—reducing the water contact angle and enhancing bacterial adhesion—which in turn reshapes colony morphology and the local concentration of autoinducers. This change in physical microenvironment likely accelerates HAI-1–mediated quorum sensing, while concurrently impeding the later CAI-1 signaling phase due to premature entry into stationary phase.

In particular, all our results are consistent with an important effect of growth dynamics on bioluminescence patterns. It is important to note that in our experimental setup for bioluminescence monitoring, the bacteria were grown on agar plates, whereas bioluminescence is usually monitored during the growth of bacteria in broth [44,47,48]. In addition, in our experiments, the bacteria were grown at 24 °C instead of 30 °C, as is usually the case, to monitor bioluminescence for a longer period of time. Unlike broth cultures, on agar plates, the emission of light follows a more complex kinetics, linked to spatiotemporal constraints determined by the geometry of colonial growth and the different accessibility of bacteria to nutrients in different regions of the colony. In some regions of the colony, the bacteria actively proliferate and emit light when a threshold density is reached, while in other regions, bacterial growth slows or stops, and the bacteria decrease or stop emitting light. In addition, the system has additional complexity due to the fact that bioluminescence in bacteria of the V. harveyi clade is not a simple function of bacterial density and growth rate, but represents the output of one of the most complex quorum-sensing cascades known, which uses three different AIs, with varying levels of integration between them and varying activation times depending on growth conditions [44,56].

In most of the cases examined, the start and intensity of light emission was correlated with growth. In the wild type V. campbellii BB120 strain, PFOA stimulates bacterial growth and, thus, induction of bioluminescence, but also premature entry into the stationary phase and, thus, abatement of bioluminescence (Figure 1) as modeled (Figure 3). Similar results were observed with the first peak of light emission of the KM387 mutant (Figure 4). The effects of PFOA on growth of bacteria on the agar surface may be due to its ability to increase the adhesion of bacteria to the substrate, as determined by measurements of the contact angle between a drop of water and the agar surface and the contact angle of between colonies and the agar surface (Figure 2). This can lead to important changes in the structural dynamics of colony growth, with flatter colonies and consequences for access to nutrients and AIs signals that regulate communication between bacteria in the colony.

4.3. PFOA Inhibits Swarming Motility

Our observations on swarming mutants (JMH603 and JAF633) further demonstrate that PFOA’s enhancement of surface adhesion prevents the collective motility required for swarming, decoupling the typical inverse regulation between motility and luminescence. By physically anchoring cells, PFOA effectively locks these mutants in a sessile state, abolishing the late swarming-associated luminescence peak.

In JMH603, the correlation analysis between bioluminescence patterns and growth dynamics was complicated by the swarming motility of bacteria, which was inhibited by PFOA. Indeed, the regular bell-shaped and elevated emission curve beginning at about 50 h and culminating at 175 h was associated with a wave of swarming on LA-CTL agar plates (Figure 6). The same inhibitory effect of PFOA on swarming motility was observed with the JAF633 mutant, which is able to produce AI-2 and CAI-1, but not HAI-1, and emitted very little light under our experimental conditions (Figure 6). The robust swarming phenotype observed in these quorum sensing-defective mutants is consistent with the evidence that bacterial motility and bioluminescence are oppositely controlled by quorum-sensing circuit [43,57]. We do not know the mechanism by which PFOA, at the concentrations used in the study, completely inhibits swarming in the two mutants, but it can be hypothesized that the increased adherence of the bacterial colony to the substrate is involved. Since bacteria moving on the surface face numerous challenges, including attracting water to the surface, overcoming frictional forces, and reducing surface tension [55], it is plausible that the presence of PFOA, which increases the adherence of bacterial colonies to the agar substrate, makes these challenges more difficult, thereby inhibiting swarming.

4.4. Limitations of the Present Study and General Implications of Quorum Sensing Dysregulation Caused by PFAS in Marine Environments

Overall, our results, although obtained in an in vitro system and a high concentration of PFOA, suggest that PFOA can strongly interfere with bacterial adhesion, colony growth, growth dynamics, swarming motility and quorum sensing-regulated processes including bioluminescence. In marine Vibrio species., quorum sensing regulates the life cycle of these bacteria, which alternates between a planktonic phase and a sessile phase characterized by symbiotic colonization of marine animals, which occasionally becomes pathogenic [40,41,42,58,59,60,61].

Bioluminescence plays an important role in mutualistic relationships between luminous Vibrio spp. and marine animals, which are well described in the squid’s light organ, where nutrients from the host are supplied to the bacterium A. fischeri (formerly known as Vibrio fischeri) in exchange for the bacterium’s ability to produce bioluminescence for a variety of purposes, including intraspecific communication with the host, camouflage against moonlight, and prey attraction [62,63]. In mutualistic relationships with many hydrozoans, Vibrio jasicida, a Vibrio species of the Harveyi clade, provides bacterial bioluminescence or specialized metabolic capabilities to occupy a nutrient-rich habitat within their host organism. The hydrozoans provide nutrients to the luminous Vibrio species within chitinous structures on its surface, and the bacteria degrade the chitinous material into forms more usable by the hydrozoans [60,64]. In addition, many hydrozoans host symbiotic dinoflagellates (zooxanthellae) that support their growth by carbon fixed photosynthetically, and V. jasicida plays a critical role in establishing/maintaining the symbiosis by consuming, through the bioluminescence reaction, excess oxygen produced by zooxanthellae, preventing the generation of reactive oxygen radicals [65,66].

Bacterial quorum sensing signals are also used for communication between bacteria and their hosts across the prokaryote-eukaryote boundary [67], and some marine organisms produce quorum sensing blockers to control epibiotic biofilm formation [68,69,70]. On the other hand, quorum sensing blockers, including 5-hydroxy-3[(1R)-1-hydroxypropyl]-4-methylfuran-2(5H)-one (FUR1), (5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-[(1S)-1,2-dihydroxyethyl]furan-2(5H)-one (FUR2), and triclosan (TRI) have been proposed as anti-biofouling agents, due to their ability to directly inhibit microbial biofilm formation and indirectly inhibit larval attachment on microbial biofilms [71]. Our results suggest that man-made “forever” chemicals such as PFAS have a disruptive effect on critical mechanisms underlying these ecological balances. These integrated insights underscore how PFOA modulates both the chemical and physical dimensions of bacterial quorum sensing, emphasizing its dual role as an indirect enhancer of early HAI-1–driven luminescence and a suppressor of later CAI-1 responses, with broad implications for marine microbial ecology.

5. Conclusions

By using a novel system, we monitored bioluminescence and other quorum sensing-relate traits during the growth of V. campbellii and isogenic quorum sensing-defective mutants on agar substrate. We demonstrated that PFOA can strongly interfere with bacterial adhesion, colony growth, growth dynamics, swarming motility and quorum sensing-regulated processes including bioluminescence and expression of virulence factors. These results may have important implications, because the quorum sensing is a critically important intraspecies and interspecies communication process in the relationships between bacteria and other organisms in the marine environments. The main limitations of the present study are represented by the fact that the results were obtained in an in vitro system and with a single, high concentration of PFOA to more easily detect its biological effects on the model bacterium used. Furthermore, the molecular mechanisms through which PFOA interferes with quorum sensing systems should be further investigated, and the analysis should be extended to PFOS and other more recently used PFAS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/applmicrobiol5040143/s1, Figure S1: Comparison of biomass and spot size in Vibrio campbellii BB120. (A) Vibrio campbellii BB120 grown on LA-PFOA. (B) Vibrio campbellii BB120 grown on LA-CTL.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: V.N. and P.A.; data curation: M.C., A.G., F.P. and S.V.; formal analysis: M.C., A.G., F.P., V.N. and P.A.; funding acquisition: F.D. and P.A.; investigation: M.C., A.G., F.P., S.V., S.M.T., F.D., V.N. and P.A.; methodology: M.C., A.G., F.P., S.V., V.N. and P.A.; project administration: F.D. and P.A.; resources: F.D., V.N. and P.A.; visualization: M.C., A.G., F.P., V.N. and P.A.; supervision: V.N. and P.A.; writing—original draft: V.N. and P.A.; writing—review & editing: M.C., A.G., F.P., S.M.T., F.D., V.N. and P.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 101037509 (SCENARIOS project). This study was partially supported by the instrumentation available at the BIOforIU Laboratory-Di.S.Te.B.A.-University of Salento (PON a3_00025).

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are available in the manuscript text.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Abbreviation

| AHL | Acyl homoserine lactone |

| AI | Autoinducer |

| AI-2 | Autoinducer-2 |

| BCF | Bioconcentration factor |

| CAI-1 | Cholera autoinducer-1 |

| dw | dry weight |

| FUR1 | 5-hydroxy-3[(1R)-1-hydroxypropyl]-4-methylfuran-2(5H)-one |

| FUR2 | (5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-[(1S)-1,2-dihydroxyethyl]furan-2(5H)-one |

| HAI-1 | Harveyi autoinducer-1 |

| LA | Luminescent Agar |

| LA-CTL | Luminescent Agar-Control |

| LA-PFOA | Luminescent agar-Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFAS | Polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFOS | Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid |

| O.D. | Optical density |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PMT | Photomultiplier |

| rpm | revolutions per minute |

| TRI | Triclosan |

References

- Lau, C.; Anitole, K.; Hodes, C.; Lai, D.; Pfahles-Hutchens, A.; Seed, J. Perfluoroalkyl Acids: A Review of Monitoring and Toxicological Findings. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 99, 366–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seacat, A.M. Subchronic Toxicity Studies on Perfluorooctanesulfonate Potassium Salt in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Toxicol. Sci. 2002, 68, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, R. Growing Concern Over Perfluorinated Chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 154A–160A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, V.; Bil, W.; Vandebriel, R.; Granum, B.; Luijten, M.; Lindeman, B.; Grandjean, P.; Kaiser, A.-M.; Hauzenberger, I.; Hartmann, C.; et al. Consideration of Pathways for Immunotoxicity of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Environ. Health 2023, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, M.N.; Riza, M.; Pervez, M.d.N.; Khyum, M.M.O.; Liang, Y.; Naddeo, V. Environmental and Health Impacts of PFAS: Sources, Distribution and Sustainable Management in North Carolina (USA). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, U.M.; Elnakar, H.; Khan, M.F. Sources, Fate, and Detection of Dust-Associated Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS): A Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.L.; Butenhoff, J.L.; Olsen, G.W.; O’Connor, J.C.; Seacat, A.M.; Perkins, R.G.; Biegel, L.B.; Murphy, S.R.; Farrar, D.G. The Toxicology of Perfluorooctanoate. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2004, 34, 351–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Butenhoff, J.L.; Rogers, J.M. The Developmental Toxicity of Perfluoroalkyl Acids and Their Derivatives. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004, 198, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manojkumar, Y.; Pilli, S.; Rao, P.V.; Tyagi, R.D. Sources, Occurrence and Toxic Effects of Emerging per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Neurotoxicology Teratol. 2023, 97, 107174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.-J.; Wei, Y.-J.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.-F. A Review of Cardiovascular Effects and Underlying Mechanisms of Legacy and Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 1195–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wen, Y.; Wang, B.; Deng, S.; Zhang, F.; Fu, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, D. Toxic Effects of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances on Sperm: Epidemiological and Experimental Evidence. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1114463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Xing, L.; Chu, J. Global Ocean Contamination of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: A Review of Seabird Exposure. Chemosphere 2023, 330, 138721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Flaws, J.A.; Spinella, M.J.; Irudayaraj, J. The Relationship between Typical Environmental Endocrine Disruptors and Kidney Disease. Toxics 2022, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, B.; Burgess, R.M.; Cantwell, M.G. Occurrence and Bioaccumulation Patterns of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in the Marine Environment. ACS EST Water 2023, 3, 1243–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Shao, Y.; Leung, K.M.Y.; Lam, P.K.S.; Ruan, Y. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in the Marine Environment: An Overview and Prospects. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 216, 117993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M.; Yang, D. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Chinese Surface Waters: A Review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 262, 115178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, G.; Mercier, L.; Duy, S.V.; Liu, J.; Sauvé, S.; Houde, M. Bioaccumulation and Trophic Magnification of Emerging and Legacy Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in a St. Lawrence River Food Web. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Li, M.; Xue, X.; Cao, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, F.; Jiang, W. Bioaccumulation and Toxicity of Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate in Marine Algae Chlorella Sp. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 870, 161882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonet-Laprade, C.; Budzinski, H.; Babut, M.; Le Menach, K.; Munoz, G.; Lauzent, M.; Ferrari, B.J.D.; Labadie, P. Investigation of the Spatial Variability of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substance Trophic Magnification in Selected Riverine Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordner, A.; Brown, P.; Cousins, I.T.; Scheringer, M.; Martinon, L.; Dagorn, G.; Aubert, R.; Hosea, L.; Salvidge, R.; Felke, C.; et al. PFAS Contamination in Europe: Generating Knowledge and Mapping Known and Likely Contamination with “Expert-Reviewed” Journalism. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 6616–6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankley, G.T.; Cureton, P.; Hoke, R.A.; Houde, M.; Kumar, A.; Kurias, J.; Lanno, R.; McCarthy, C.; Newsted, J.; Salice, C.J.; et al. Assessing the Ecological Risks of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: Current State-of-the Science and a Proposed Path Forward. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2020, 40, 564–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, A.; Vlastos, D.; Antonopoulou, M. Evidence on the Genotoxic and Ecotoxic Effects of PFOA, PFOS and Their Mixture on Human Lymphocytes and Bacteria. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Kelso, C.; Hai, F. Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (PFOS) Adsorption onto Different Adsorbents: A Critical Review of the Impact of Their Chemical Structure and Retention Mechanisms in Soil and Groundwater. Water 2025, 17, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, M.R.; Aris, A.Z.; Zainuddin, A.H.; Yusoff, F.M.; Balia Yusof, Z.N.; Kim, S.D.; Kim, K.W. Acute Toxicity and Risk Assessment of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) in Tropical Cladocerans Moina Micrura. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wackett, L.P. Nothing Lasts Forever: Understanding Microbial Biodegradation of Polyfluorinated Compounds and Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwain, B.C.; Ruprecht, M.T.; Stockbridge, R.B. Membrane Exporters of Fluoride Ion. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2021, 90, 559–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Li, B.; Xie, S.; Huang, J. Vertical Profiles of Microbial Communities in Perfluoroalkyl Substance-Contaminated Soils. Ann. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, X.; Tong, T.; Huang, J.; Xie, S. Emerging Perfluoroalkyl Substance Impacts Soil Microbial Community and Ammonia Oxidation. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Arevalo, E.; Strynar, M.; Lindstrom, A.; Richardson, M.; Kearns, B.; Pickett, A.; Smith, C.; Knappe, D.R.U. Legacy and Emerging Perfluoroalkyl Substances Are Important Drinking Water Contaminants in the Cape Fear River Watershed of North Carolina. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, 3, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, T.; Peng, X.; Wang, P.; Lu, Y. Bacterial Community Compositions in Sediment Polluted by Perfluoroalkyl Acids (PFAAs) Using Illumina High-Throughput Sequencing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 10556–10565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, W.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Xie, S.; Huang, J.; Yu, L. Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) Influence the Structure and Function of Soil Bacterial Community: Greenhouse Experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Liang, Y. Distribution of Eight Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Plant-Soil-Water Systems and Their Effect on the Soil Microbial Community. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 697, 134146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, W.; Liang, Y. Bacterial Community in a Freshwater Pond Responding to the Presence of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). Environ. Technol. 2020, 41, 3646–3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, R.; Wang, F.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, B. Metagenomic Analysis of Soil Microbial Community under PFOA and PFOS Stress. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagnile, M.; Giuliano, A.; Tredici, M.S.; Gualandris, D.; Rotondo, D.; Calisi, A.; Leo, C.; Martelli, M.; Rocchi, A.; Klint, K.E.; et al. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) as Environmental Drivers of Antimicrobial Resistance: Insights from Genome Sequences of Klebsiella grimontii and Citrobacter braakii Isolated from Contaminated Soil. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2025, 4, 1444–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.B.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum Sensing in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 165–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, J.M.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum Sensing Regulates Type III Secretion in Vibrio Harveyi and Vibrio Parahaemolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 3794–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, J.M.; Bassler, B.L. Three Parallel Quorum-Sensing Systems Regulate Gene Expression in Vibrio Harveyi. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 6902–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defoirdt, T.; Boon, N.; Sorgeloos, P.; Verstraete, W.; Bossier, P. Quorum Sensing and Quorum Quenching in Vibrio Harveyi: Lessons Learned from in Vivo Work. ISME J. 2008, 2, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, C.; Finkel, S.E. Vibrio Harveyi Exhibits the Growth Advantage in Stationary Phase Phenotype during Long-Term Incubation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0214421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, B.; Zhang, X.-H. Vibrio Harveyi: A Significant Pathogen of Marine Vertebrates and Invertebrates. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 43, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montánchez, I.; Kaberdin, V.R. Vibrio Harveyi: A Brief Survey of General Characteristics and Recent Epidemiological Traits Associated with Climate Change. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 154, 104850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, C.M.; Bassler, B.L. The Vibrio Harveyi Quorum-Sensing System Uses Shared Regulatory Components to Discriminate between Multiple Autoinducers. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 2754–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anetzberger, C.; Reiger, M.; Fekete, A.; Schell, U.; Stambrau, N.; Plener, L.; Kopka, J.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Hilbi, H.; Jung, K. Autoinducers Act as Biological Timers in Vibrio Harveyi. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, N.J.M.; Simcik, M.F.; Novak, P.J. Perfluoroalkyl Substances Increase the Membrane Permeability and Quorum Sensing Response in Aliivibrio fischeri. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2018, 5, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattano, J.; Dechathai, T.; Chaichanit, N.; Surachat, K.; Jetwanna, K.W.; Srinitiwarawong, K.; Mittraparp-arthorn, P. Genomic Adaptations of Vibrio Campbellii to Thermal and Salinity Stress: Insights into Marine Pathogen Resilience in a Changing Ocean. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaparian, R.R.; Ball, A.S.; van Kessel, J.C. Hierarchical Transcriptional Control of the LuxR Quorum-Sensing Regulon of Vibrio Harveyi. J. Bacteriol. 2020, 202, e00047-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, C.A.; Petersen, B.D.; Haas, N.W.; Geyman, L.J.; Lee, A.H.; Podicheti, R.; Pepin, R.; Brown, L.C.; Rusch, D.B.; Manzella, M.P.; et al. The Quorum-Sensing Systems of Vibrio Campbellii DS40M4 and BB120 Are Genetically and Functionally Distinct. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 5412–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wang, Z.; Malanoski, A.P.; O’Grady, E.A.; Wimpee, C.F.; Vuddhakul, V.; Alves, N.; Thompson, F.L.; Gomez-Gil, B.; Vora, G.J. Comparative Genomic Analyses Identify the Vibrio Harveyi Genome Sequenced Strains BAA-1116 and HY01 as Vibrio Campbellii. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2010, 2, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talà, A.; Calcagnile, M.; Resta, S.C.; Pennetta, A.; De Benedetto, G.E.; Alifano, P. Thiostrepton, a Resurging Drug Inhibiting the Stringent Response to Counteract Antibiotic-Resistance and Expression of Virulence Determinants in Neisseria Gonorrhoeae. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1104454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talà, A.; Delle Side, D.; Buccolieri, G.; Tredici, S.M.; Velardi, L.; Paladini, F.; De Stefano, M.; Nassisi, V.; Alifano, P. Exposure to Static Magnetic Field Stimulates Quorum Sensing Circuit in Luminescent Vibrio Strains of the Harveyi Clade. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Be’er, A.; Ariel, G. A Statistical Physics View of Swarming Bacteria. Mov. Ecol. 2019, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.C. Swarming Motility: It Better Be Wet. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, R599–R600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnton, N.C.; Turner, L.; Rojevsky, S.; Berg, H.C. Dynamics of Bacterial Swarming. Biophys. J. 2010, 98, 2082–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, J.D.; Harshey, R.M. Swarming: Flexible Roaming Plans. J. Bacteriol. 2013, 195, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plener, L.; Lorenz, N.; Reiger, M.; Ramalho, T.; Gerland, U.; Jung, K. The Phosphorylation Flow of the Vibrio Harveyi Quorum-Sensing Cascade Determines Levels of Phenotypic Heterogeneity in the Population. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 1747–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Q.; Deng, Y.-Q.; Feng, J.; Hu, J.-M.; Chen, H.-X.; Guo, Z.-X.; Su, Y.-L. LuxS Modulates Motility and Secretion of Extracellular Protease in Fish Pathogen Vibrio Harveyi. Can. J. Microbiol. 2022, 68, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Ferreira, R.; Gorman, C.; Chavez, A.A.; Willie, S.; Nishiguchi, M.K. Characterization of the Bacterial Diversity in Indo-West Pacific Loliginid and Sepiolid Squid Light Organs. Microb. Ecol. 2013, 65, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonthornchai, W.; Chaiyapechara, S.; Jarayabhand, P.; Söderhäll, K.; Jiravanichpaisal, P. Interaction of Vibrio Spp. with the Inner Surface of the Digestive Tract of Penaeus Monodon. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabili, L.; Licciano, M.; Giangrande, A.; Fanelli, G.; Cavallo, R.A. Sabella Spallanzanii Filter-Feeding on Bacterial Community: Ecological Implications and Applications. Mar. Environ. Res. 2006, 61, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabili, L.; Cardone, F.; Alifano, P.; Tredici, S.M.; Piraino, S.; Corriero, G.; Gaino, E. Epidemic Mortality of the Sponge Ircinia Variabilis (Schmidt, 1862) Associated to Proliferation of a Vibrio Bacterium. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 64, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongrand, C.; Koch, E.J.; Moriano-Gutierrez, S.; Cordero, O.X.; McFall-Ngai, M.; Polz, M.F.; Ruby, E.G. A Genomic Comparison of 13 Symbiotic Vibrio Fischeri Isolates from the Perspective of Their Host Source and Colonization Behavior. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2907–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, E.G. Lessons from a Cooperative, Bacterial-Animal Association: The Vibrio Fischeri-Euprymna Scolopes Light Organ Symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1996, 50, 591–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabili, L.; Gravili, C.; Tredici, S.M.; Piraino, S.; Talà, A.; Boero, F.; Alifano, P. Epibiotic Vibrio Luminous Bacteria Isolated from Some Hydrozoa and Bryozoa Species. Microb. Ecol. 2008, 56, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabili, L.; Gravili, C.; Boero, F.; Tredici, S.M.; Alifano, P. Susceptibility to Antibiotics of Vibrio Sp. AO1 Growing in Pure Culture or in Association with Its Hydroid Host Aglaophenia Octodonta (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa). Microb. Ecol. 2010, 59, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stabili, L.; Gravili, C.; Pizzolante, G.; Lezzi, M.; Tredici, S.M.; De Stefano, M.; Boero, F.; Alifano, P. Aglaophenia Octodonta (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) and the Associated Microbial Community: A Cooperative Alliance? Microb. Ecol. 2018, 76, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint, I.; Tait, K.; Callow, M.E.; Callow, J.A.; Milton, D.; Williams, P.; Cámara, M. Cell-to-Cell Communication across the Prokaryote-Eukaryote Boundary. Science 2002, 298, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, W.D.; Robinson, J.B. Disruption of Bacterial Quorum Sensing by Other Organisms. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002, 13, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manefield, M.; de Nys, R.; Naresh, K.; Roger, R.; Givskov, M.; Peter, S.; Kjelleberg, S. Evidence That Halogenated Furanones from Delisea Pulchra Inhibit Acylated Homoserine Lactone (AHL)-Mediated Gene Expression by Displacing the AHL Signal from Its Receptor Protein. Microbiology 1999, 145, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.-H.; Dong, Y.-H. Quorum Sensing and Signal Interference: Diverse Implications. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobretsov, S.; Dahms, H.-U.; Yili, H.; Wahl, M.; Qian, P.-Y. The Effect of Quorum-Sensing Blockers on the Formation of Marine Microbial Communities and Larval Attachment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2007, 60, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).