Abstract

Chemical fungicides play a key role in protecting crops, but their use can result in environmental problems. We tested a novel fungicide, composed of endophytic microorganisms, for its effect on wheat yield, grain quality, plant development, and the rhizosphere microbiome, assessed by 16S and ITS metabarcoding. The fungicide increased the grain yield, the effect being similar to a well-known commercial bacterial fungicide, without affecting its quality. Ascomycota, Zygomycota and Mucoromycota together comprised 80% of the mycobiome. Mucoromycota/Mucoromycetes/Rhizopodaceae/Rhizopus arrhizus were significantly decreased. The dominant (≥10%) bacterial phyla were Pseudomonadota, Acidobacteriota, Bacteroidota and Actinomycetota, but their fungicide-related differences were small or random. Different modes of fungicide application (seeds only, seeds plus one or two foliar applications) had no effect on wheat characteristics. Neither of the fungicide’s agents (Raoultella ornithinolytica and Pantoea allii) were found in the rhizosphere. The changes in the mycobiome seemed more pronounced than in the bacteriobiome. The proposed preparation is concluded to have good prospects as a fungicide. However, the low species/strain resolution of the DNA metabarcoding did not allow us to fully interpret shifts in the microbiome diversity, both agronomically and environmentally. These aspects need more comprehensive investigation, using methodology with higher species resolution.

Keywords:

16S rRNA genes; ITS; soil bacteria; soil fungi; metabarcoding; NGS; Chernozem; wheat diseases; West Siberia 1. Introduction

Microbial diseases and disorders of grains and the products of their processing are a serious problem in grain-producing countries: fungal diseases are widespread in southern Russia, including the south of West Siberia [1,2], sometimes causing up to a 70% decrease in yields and grain quality and, hence, food safety. Fungal pathogens cause many diseases of wheat, the main ones being ear fusariosis, alternariosis, helminthosporiosis, ergot and smut.

Fusarium graminearum is a major plant-pathogenic fungus that causes serious disease in wheat and maize, decreasing yield in both crops and producing mycotoxins that pose a risk to human and animal health [3]. Ear fusariosis, caused by a range of Fusarium species (F. graminearum, F. avenaceum and F. culmorum), also results in decreased yields and grain quality, as well as an accumulation of mycotoxins. The presence of the pathogens appears in the form of root browning, decay and die-off of roots, and belowground internodes and stems, leading to root rot, thinning of wheat plantations and empty ears [4]. Pink sporomorphs develop on the ear husks and grains, the latter becoming thinner and losing the ability to germinate. Phytosanitary surveys, conducted in 2024 in the region of this study on 18,590 hectares of spring grain crops, revealed Fusarium head blight infection in 5910 hectares, with the highest prevalence rate in one of the surveyed districts reaching 20% on an area of 260 hectares [5].

Alternariosis blight, caused by Alternaria spp. (for instance, A. alternata), affects leaves and grains, decreasing the sowing and food qualities of the latter. Fungal mycelium accumulates in grain husks and endosperm, causing symptoms of black point in wheat and barley. Some strains of the Alternaria genus can produce toxins that are dangerous to plants, animals and humans.

Helminthosporiosis, caused by Bipolaris sorokiniana, affects all plant organs, causing spotting and root and stem rot and thus decreasing yields. Ergot, caused by the Claviceps purpurea fungus, is dangerous because the fungus develops sclerotia, containing toxic alkaloids, thus preventing the grain from being used as food or fodder. Smut, caused by the Tilletia fungi (such as T. caries and T. tritici), results in partial or even total substitution of grains by smut sori, thus seriously decreasing grain yields and quality [6].

Effective mitigation of grain crop diseases needs a combined approach, including using resistant varieties, crop rotation, seed treatment, fungicide application and adequate grain storage. In modern agriculture, chemical pesticides, including fungicides, play a key role in protecting crops from phytopathogens. However, despite their efficacy, the widespread use of chemical compounds for plant protection can result in some serious environmental and ecological problems. Due to their high stability, pesticides can persist in the environment, contaminating soil, water and the atmosphere [7]. Due to their ability of bioaccumulation [8], pesticides can enter food webs, thus being hazardous to humans and animals. Long-term use of chemical fungicides can also affect the microbial diversity of the rhizosphere and phyllosphere, potentially decreasing the activity of beneficial microorganisms, such as nitrogen-fixing rhizobacteria, and hence decreasing crop productivity [9]. Therefore, development of novel preparations with anti-phytopathogenic activity has been increasing [10]. As the World Food and Agriculture Organization urges increasing ecological and environmental safety of agricultural systems, biopesticides, obtained via microbial synthesis, represent a potential alternative to chemical preparations since they do not accumulate in the environment and are safe for humans and animals [11]. The novel fungicide proposed in this study is intended to exert a range of positive effects on plants, i.e., not only by directly fighting phytopathogens, but also supplying a range of beneficial secondary metabolites, such as phytohormones and antioxidants [12]. Of special interest are extremophilic microorganisms, possessing unique physiological and biochemical properties that allow survival in harsh environments [13]. We decided to test the efficacy and ecological safety of a novel biological fungicide preparation, composed of endophytic microorganisms isolated from natural environments in the Kuzbass (Kemerovo Region, Russia) [14,15], to increase wheat grain yield and quality, as well as plants’ growth and development characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

The study was carried out at the demonstration site of the LLC “Azot-Agro”, located near Zvezdny settlement (Kuzbass, Kemerovo region, Russia: 55.435900 N, 85.816400 E).

The climate of the region is temperate, with annual temperature and precipitation, as averaged over 1991–2000, being +1.6 °C and 529 mm, respectively [16] (Hydrometcenter of Russia, 2025). Monthly temperature and precipitation in January, as averaged over the same 30-year period, is −17.3 °C and 70 mm, the respective values for July being +19.3 °C and 297 mm. Winters are cold and long, while summers are short and warm.

Experimental plots were 6.7 m long and 1.5 m wide. The soil of the site (leached heavy-loam Chernozem) had pH = 5.0, 7.0% of humus, 15 ÷ 20 mg NO3, 65 ÷ 100 mg P2O5 and 80 ÷ 120 mg K2O per kilogram of oven-dried soil. During the vegetation season, commercial herbicides, namely Aksial (Syngenta, Lipetsk, Russia), Eurostart (LLC Agrochim XXI, Moscow, Russia) and Elant (LLC Chimiya, Novosibirsk, Russia), and insecticides Fastak (Agrochem, Krasnodar, Russia) and Contador (Garant Optima LLC AFD, Belgorod, Russia) were used according to the wheat agronomy in the region.

2.2. Fungicides Used in the Experiment

Commercial chemical and biological fungicides were used in the study for comparison with the novel one. As the chemical fungicide treatment, a combination of “Sistiva” (fluxapyroxad suspension, 333 g/L) and “Inshur” (triticonazole 80 g/L + pyraclostrobin, 40 g/L), both produced by BASF (Germany), was used as recommended by the manufacturer for cereals, specifically for treating seeds at rates of 0.7 L and 0.5 L per ton of seeds, respectively, plus one foliar treatment at the tillering phase at 0.7 L and 0.5 L per hectare, respectively. As a biological fungicide, we used “Bactophyte” (a registered strain of Bacillus subtillis) produced by LLC “Sibbiofarm” (Russia), applied at the rate of 2 L of suspension per ton for seeds and 2 L per hectare for two foliar applications. As a novel fungicide, we used a consortium of the Raoultella ornithinolytica strain and two strains of Pantoea allii at the ratio 1:1:1. In the laboratory, in vitro testing of the consortium proved to be effective in mitigating the effect of Fusarium graminearum, Bipolaris sorokiniana and Botrytis cinerea on wheat seed germination and plantlet growth and development [17]. The consortium was cultivated at 28 ± 2 °C for 24 h at 110 rpm in the following medium: 8 g/L of pancreatic hydrolysate of fish meal, 8 g/L of fermented meat peptone, 5 g/L of NaCl, 30 g/L of tryptone and 3 g/L of tryptophane. To make a working solution, the produced bacterial concentrate was diluted with water in a ratio of 2:8, and this suspension was applied at the rate of 2 L per ton of seeds or per hectare for foliar applications.

The characteristics of the individual strains and fungicide used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of individual strains and fungicide.

2.3. Experimental Setup

The plots were cropped for soft spring wheat of the “Extra” variety, included in the Russian Register of Selection Achievements since 2020 and in the West Siberian region producing 2.8 t/ha on average with a maximum of 6.35 t/ha. The cultivar is known to be susceptible to a range of fungal diseases, especially dusty smut. There were six different treatments in the experiment: without any fungicide (F0), with the chemical fungicide (F1), with the biological fungicide (F2) and with the novel preparation (F3), the latter with three modes of application: seed treatment only (F3(0)), seed treatment followed by one foliar application (F3(1)), and seeds only followed by two foliar applications at the panicle-producing stage with 12-day intervals (F3(2)). Commercial fungicides were applied as per the manufacturer’s instructions: for the F1 treatment, the chemical fungicide was applied for treating seeds followed by one foliar application, the application being at the rate of 0.7 L and 0.5 L per ton of seeds or per hectare for foliar treatment at the tillering phase. For the F2 and F3 treatments, the fungicides were applied for treating seeds, followed by two foliar applications at tillering and tubing stages at the rates of 2 L of suspension per ton for seeds and 2 L per hectare for two foliar applications. The control treatment received no application.

According to the in vitro testing, using the standard technique [19], i.e., incubating in a moist camera and visually counting infested seeds, 12.6% of the seeds, used for the field trial, were infected.

2.4. Wheat Sampling and Analyses

The experiment was performed with spring wheat of the Extra variety, which was included in the Russian Registry of Selection in 2020. The variety’s 1000-grain weight was 32 ÷ 45 g. In West Siberia, the average yield is 2.8 t, whereas the maximum was recorded as 6.4 t per hectare. The vegetation period to reach mean maturity ranges 71–96 days. The variety is known as moderately susceptible to septoriosis and susceptible to root rot, being strongly susceptible to hard smut, powdery mildew, and brown and stem rust; under field conditions the plants were severely affected by dusty smut.

To assess the agrobiological properties of plants, whole plants were collected from a 1 m2 area in five replicates from each plot. Then we counted the number of plants, stems, and stems with ears, and measured plant mass, plant height, ear length and the number of grains in an ear. The yield and the mass of 1000 grains and of 1 L of grain were determined after harvesting wheat from the entire treatment plots. Grain quality properties were determined using the infra-red food analyzer Infrascan-4200 (Ecan, Saint-Petersburg, Russia).

2.5. Rhizosphere Soil Sampling

The rhizosphere soil was collected at the same time as wheat plants in the second half of August 2024 in five samples, distanced 20 cm from each other. To avoid drying during the transportation to the laboratory, plants and soil were immediately sealed in polyethylene bags [20]. To collect the rhizosphere soil, roots were gently shaken and the remaining soil was scooped from the roots by a spatula, sieved through a 2 mm sieve and placed into a polyethylene bag. Prior to DNA extraction, soil samples were stored at –80 °C.

2.6. DNA Extraction, Purification and Sequencing

Total DNA was extracted from 0.2 g of samples using the ZymoBIOMICS DNA Microprep Kit (Zymo Research Corp., Irvine, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Bead-beating was performed using TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for 10 min at 30 Hz. The quantity was analyzed by a Nanodrop-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Walham, MA, USA) and Qubit (Invitrogen, Moscow, Russia). The quality of the DNA was assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis.

16S rRNA genes were amplified with the primer pair V3-V4 [21], and the ITS2 [22] fragments were amplified with primer pairs 343F/806R and ITS3_KYO2/ITS4. Sequencing was also performed at the Genomics Core Facility of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Institute of Chemical Biology and Fundamental Medicine, SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia). The read data reported in this study were submitted to the NCBI Short Read Archive under bioproject accession number PRJNA1320511 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1320511, accessed on 14 September 2025).

2.7. Bioinformatic Analysis

The bioinformatic analysis was performed as follows: we analyzed raw sequences with UPARSE pipeline [23] and used Usearch v.11.0.667, the UPARSE-OTU algorithm, and SINTAX [23] for the taxonomic attribution, referenced to the 16S RDP training set v.19 [24] and ITS UNITE USEARCH/UTAX v.8.3. The UPARSE pipeline included merging of paired reads; read quality filtering (-fastq_maxee_rate 0.005); length trimming (removing less 100 nt); merging of identical reads (dereplication); discarding singleton reads; removing chimeras; and operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering at a 97% similarity threshold using the UPARSE-OTU algorithm.

The operational taxonomic unit (OTU) datasets were analyzed by individual rarefaction with the help of the PAST software v. 4.16c [25]: the numbers of bacterial OTUs detected, reaching a plateau with an increasing number of sequences, showed that the sampling effort was close to saturation for all samples, thus being enough to compare diversity on the non-rarefied data sets [26].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses (descriptive statistics, ANOVA, PCA, ANOSIM and PERMANOVA) were performed by using Statistica v.13.3 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA) and PAST [25] software packages. Post hoc comparisons of differences between treatment means (by Fisher’s LSD test) were considered statistically significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level.

3. Results

3.1. Wheat Yield, Grain Quality and Development Parameters as Related to the Treatment with Different Fungicides

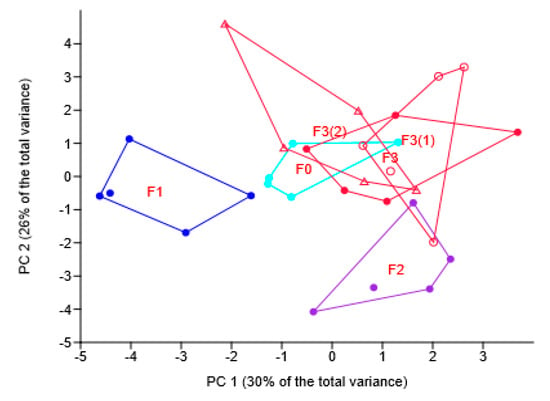

The use of different fungicides differentially affected wheat yield, grain quality and growth and development characteristics (Table 2), the corresponding samples tending to separate in the plane of the first two principal components (Figure 1). The consortium increased the grain yield and some growth and development characteristic, specifically the number of plants, stems and stems with ears per 1 m2, but did not affect grain quality.

Table 2.

Wheat yield, grain quality and growth and development characteristics under treatment with different fungicides (mean ± standard deviation). Codes for treatments: F0—no fungicide; F1—chemical f2ungicide; F2—biological fungicide; F3—the novel preparation with three modes of application: seed treatment only, F3(0); seed treatment followed by one foliar application, F3(1); and seeds only followed by two foliar applications, F3(2).

Figure 1.

Principal component (PC) analysis of wheat grain quality and development characteristics under different fungicide treatments: location of samples in the plane of PC1 and PC 2. Codes for treatments: F0—no fungicide; F1—chemical fungicide; F2—biological fungicide; F3—the novel preparation with three modes of application: seed treatment only, F3(0); seed treatment followed by one foliar application, F3(1); and seeds only followed by two foliar applications, F3(2).

3.2. Wheat Yield, Grain Quality and Development Parameters as Related to the Different Modes of Application of the Novel Fungicide

The novel fungicide (F3) was tested not only by treating seeds (F3) but also by foliar application, which was carried out either once (F3(1)) or twice (F3(2)) during the growing season. Multivariate ANOVA resulted in no effect of the treatment (p = 0.788), the univariate results being similar.

3.3. Soil Mycobiome in Wheat Rhizosphere

Overall, 2800 fungal OTUs were discovered in this study. They belonged to 568 genera, 317 families, 134 orders, 63 classes and 17 phyla. One cluster remained unidentified below the domain level of Fungi, but was the most OTU-rich, containing 1156, or 41%, of the discovered OTUs. The Ascomycota phylum contained 878 OTUs (31% of the total number of OTUs), whereas 520 OTUs (18.5%) belonged to Basidiomycota. These were followed by Chytridiomycota with just 122 OTUs (4%), whereas the rest of the 14 phyla had just several OTUs each.

As for the relative abundance, on average Ascomycota accounted for 49.0 ± 7.4% of the total number of sequence reads in the study, whereas Zygomycota and Mucoromycota contributed 20.1 ± 7.8% and 13.0 ± 5.9%, respectively. Notably, Basidiomycota’s relative abundance (5.5 ± 2.5%) was even less than that of the unclassified Fungi, the latter accounting for 8.9 ± 3.1%. Of the 17 phyla, identified in the study, five were major dominants (Ascomycota, Zygomycota, Mucoromycota, Basidiomycota and Chytridiomycota), with unclassified Fungi accounting for practically all (99%) the sequence reads obtained.

3.3.1. Soil Mycobiome as Related to Different Fungicides

In each treatment Ascomycota, Mucoromycota and Zygomycota were the major dominant phyla, together contributing slightly more than 80% of the relative abundance (Table 3). The soil mycobiome of all treatments had five dominants, mentioned above, but F2 treatment added Mortierellomycota to the dominants’ list, although with just 1.5% of the relative abundance.

Table 3.

The relative abundance of the dominant phyla and classes of soil mycobiome under wheat treated with different fungicides. Codes for treatments are the same as in Table 2.

At the class level, the number of the dominants ranged 9–10 under different fungicides, the four ultimate dominants (Sordariomycetes, Dothideomycetes, Mucoromycetes and Mucoromycotina_is) summarily accounting for about 75% of the total number of sequence reads and displaying some differential changes due to fungicide treatments (Table 3).

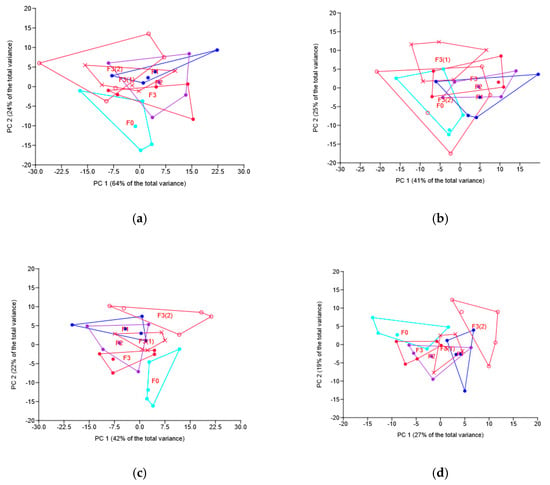

There were some differences between the treatments in the relative abundance of the prevailing taxa; the results for the dominant phyla, classes, families and OTUs are shown in Table 3 and Table 4 and Figure 2. At the phylum level there was a difference in Ascomycota between different F3 treatments, but all three F3 treatments did not differ from the one with no fungicide applied (Table 3). Zygomycota was increased almost two times by both commercial fungicides, but not the novel one, whereas Mucoromycota was almost twice decreased in all treatments, except the seed-only one, i.e., F3. Basidiomycota was also decreased by the two commercial fungicides as compared with the no-fungicide treatment. Although F3(1) treatment differed in Basidiomycota abundance from F3 and F3(2), all three novel fungicide treatments did not differ from the no-fungicide one. The latter was also true for the Chytridiomycota phylum, although F3(1) in this case differed from F3 (Table 3).

Table 4.

The relative abundance of the dominant families and OTUs of the soil mycobiome under wheat treated with different fungicides. Codes for treatments are the same as in Table 2.

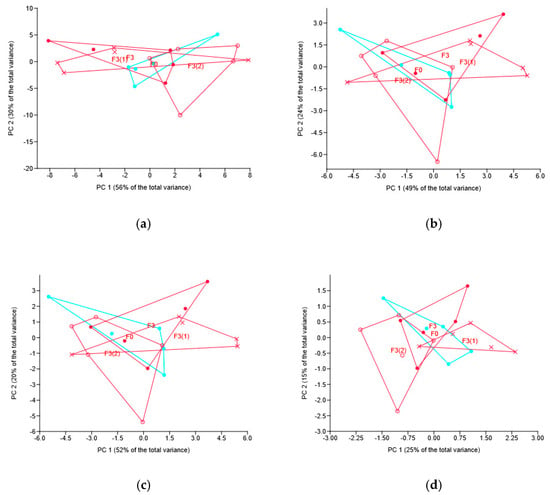

Figure 2.

Principal component (PC) analysis of the fungal taxa relative abundance under different fungicide treatments: location of samples in the plane of PC1 and PC 2. Graphs based on phyla (a), classes (b), families (c) and OTUs (d). Codes for treatments are the same as for Figure 1.

At the OTU level, Rhizopus arrhizus, Stachybotrys bisbyi and some unclassified Pleosporales, Pleosporaceae, Hypocreales, and Tetracladium sp_WMM_2012d revealed the pattern of relative abundance changes, most consistent with the fungicides’ treatments (Table 4). The novel fungicide increased significantly when applied on seeds only, but foliar treatments, unexpectedly, did not show a similar result.

At the class level there were also some differences in the dominants’ abundance, the most consistent with the fungicides’ treatment being Mucoromycetes and Agaricomycetes.

As for the family level, notable changes were observed in the relative abundance of the major dominants: F1 and F2 treatments increased the abundance of Mortierellaceae 2-fold (Table 4), the p value for the increase under F3 being 0.076. Rhizopodaceae decreased its abundance 2-fold under F1 and F2 treatments. All three applied fungicides significantly decreased the relative abundance of Hypocreales_is, and increased that of some families, belonging to unclassified Hypocreales (Table 4). Several dominant families did not at all respond to the fungicide treatment.

3.3.2. Soil Mycobiome as Related to the Different Modes of the Novel Fungicide Application

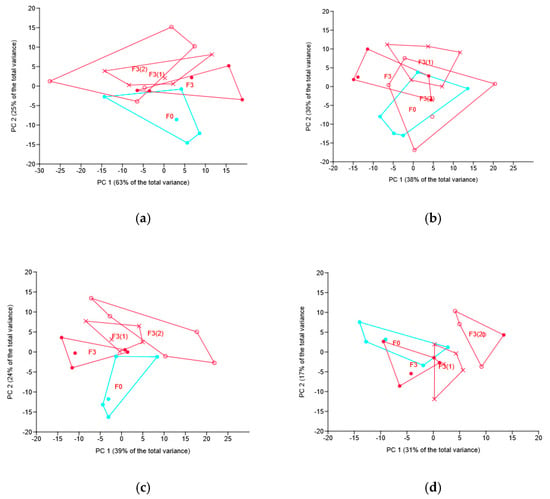

At the phylum level, Mucoromycota’s relative abundance in both treatments with foliar application of the fungicide was more than two times lower as compared with the control (no-fungicide) treatment (8.7 and 8.2% vs. 18.3, p = 0.012 and p = 0.008, respectively). The F3 treatment (13.6%) differed neither from the control one nor from both treatments involving foliar application. Interestingly, Basidiomycota was almost twice increased in the F3(1) treatment as compared with the F3 (9.3 vs. 5.4%, p = 0.026) and the F3(2) treatment (9.3 vs. 5.3%, p = 0.022). However, PERMANOVA, based on the Euclidean distance, revealed no significant differences between the treatments; the result is supported by the location of soil samples in the plane of the first two principal components (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Principal component (PC) analysis of the soil mycobiome taxa abundance under different modes of the novel fungicide application: location of samples in the plane of PC1 and PC 2. Graphs based on phyla (a), classes (b), families (c) and OTUs (d). Codes for treatments are the same as for Figure 2.

For the class level, PERMANOVA revealed some difference between the seed-only treatment (F3) as compared with one or two foliar treatments, i.e., F3(1) or F3(2), during the growing season: for the F3 vs. F3(1) comparison, p = 0.086, and for F3 vs. F3(2), p = 0.043.

At the family level, PERMANOVA revealed the difference between F3 and F3(2) treatment, with the difference between F3(1) and both F3 and F3(2) having p-values of 0.095 and 0.086, respectively. All three treatments with the novel fungicide differed significantly from the no-fungicide treatment, with the relationship visualized in Figure 3c.

At the OTU level, PERMANOVA showed significant difference between F3(2) and F3(1) (p = 0.035), and F3(2) and F3 treatments (p = 0.009), as well as with the no-fungicide treatment (p = 0.008). Both foliar treatments differed from the no-fungicide one (for F3(1) vs. F0 p = 0.047 and for F3(2) vs. F0 p = 0.008), but seed-only treatment did not differ (p = 0.117).

3.4. Soil Bacteriobiome in Wheat Rhizosphere

Overall, in this study 3559 bacterial OTUs were found, belonging to 471 genera, 256 families, 154 orders, 83 classes and 23 phyla. The most OTU-rich phylum was Pseudomonadota (969 OTUs, or 27% of the total number of OTUs in the study). The second-ranked in this respect was a cluster not identified below the domain level (unclassified Bacteria) comprising 544 OTUs (15%). Such universal soil phyla as Actinomycetota, Acidobacteriota, Verrucomicrobiota and Bacteroidota contributed 10, 11, 5 and 12%, respectively, to the total number of OTUs.

3.4.1. Soil Bacteriobiome as Related to Different Fungicides

There were some differences between the treatments in the relative abundance of the dominant bacterial taxa. For instance, Pseudomonadota increased their abundance by almost 3% under F3(2) as compared with F0 treatment (Table 5), with Verrucomicrobiota displaying the opposite pattern. Chemical fungicide treatment, i.e., F1, was the only one that resulted in notable decreases in Bacteriodota and the cluster of unclassified Bacteria, as compared with not only F0 treatment, but with the rest of the others as well. The F1 treatment also resulted in increased Chloroflexota abundance, as compared with F3(1) and F3(2) (Table 5).

Table 5.

The relative abundance of the dominant phyla and classes of soil bacteriobiome under wheat treated with different fungicides. Codes for treatments are the same as in Table 2.

Among the dominant classes, Alphaproteobacteria increased ca. 3% under F3(2) as compared with all other treatments (Table 5). Chitinophagia was notably (also ca. 3%) decreased by F1 as compared with F0, F2 and F3(2). Acidobacteria_Gp6 was increased only under F3(1) treatment, whereas Betaproteobacteria was higher under F3(2). Acidobacteria_Gp4 was slightly increased under both F1 and F2 treatments. Deltaproteobacteria displayed a difference only between F3(1) and F3(2) treatments, the latter also having a higher abundance of Cytophagia as compared with F1 treatment.

Chitinophagaceae’s abundance under F1 was about 3% lower than under F0, F2 and F3(2) (Table 6). Some unclassified families of Acidobacteria_Gp6 had differential abundance between F0 and F3(1), whereas some unclassified families of Acidobacteria_Gp4 had differential abundance between F0 and F1 and between F3 and F1. Sphingomonadaceae was 1.0–1.4% higher under F3 and F3(2). There was a slight difference in the Bradyrhizobiaceae abundance between F3 and F3(2), the pattern repeated by some Bradyrhizobium spp. (Table 6). All three treatments with F3 differed from each other, as well as from F0, in Sphingomonas sp. abundance. The F2 treatment had slightly decreased abundance of Pseudarthrobacter sp. than F0. Some unclassified OTU-level clusters of Acidobacteria_Gp4 were higher in abundance under F1 and F2 than under F0.

Table 6.

The relative abundance of the dominant families and OTUs of soil bacteriobiome under wheat treated with different fungicides. Codes for treatments are the same as in Table 2.

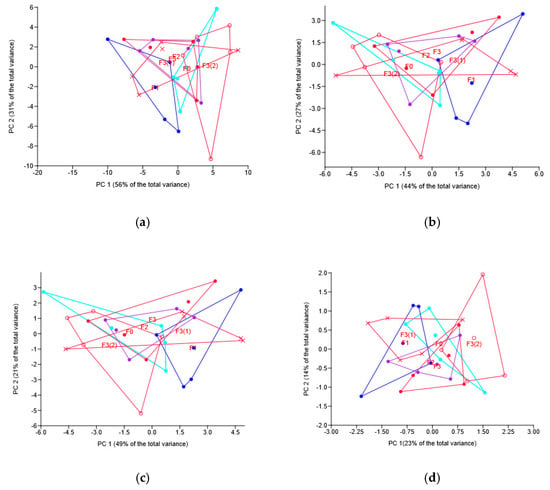

The structure of relationships among rhizosphere soil samples is visualized in Figure 4, at all taxa levels showing separation of F0 and F1 treatment samples.

Figure 4.

Principal component (PC) analysis of the bacterial taxa relative abundance under different fungicide treatments: location of samples in the plane of PC1 and PC 2. Graphs based on phyla (a), classes (b), families (c) and OTUs (d). Codes for are the same as for Figure 1.

3.4.2. Soil Bacteriobiome as Related to the Different Modes of the Novel Fungicide Application

At the phylum, class and family levels, multivariate analyses (ANOSIM and PERMANOVA) showed no effect of the fungicide application mode, the pattern confirmed by the multivariate (PCA) ordination (Figure 5). At the OTU level, though, PERMANOVA revealed the difference between F3(1) and both F3 and F3(2), the p-values for the respective pairwise comparison being 0.042 and 0.015. The same pattern of relationship was revealed by ANOSIM based on Euclidean distance and confirmed by the sample location pattern (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Principal component (PC) analysis of the soil bacteriobiome taxa abundance under different modes of novel fungicide application: location of samples in the plane of PC 1 and PC 2. Graphs based on phyla (a), classes (b), families (c) and OTUs (d). Codes for treatments are the same as for Figure 1.

4. Discussion

4.1. Wheat Yield, Grain Quality and Development Parameters as Related to the Treatment with Different Fungicides

As the grain yield increased in comparison to without any fungicide, the effect of the novel fungicide was similar to that of the widely distributed commercial bacterial fungicide, produced by a prominent global company. As for the grain quality characteristics, the protein content in all three treatments with the novel fungicide, i.e., seeds only and one and two foliar applications, did not differ from the that in the grain obtained without any fungicide. The same goes for the other grain quality characteristics. As bigger yields and better grain quality are the ultimate goals of fungicide application, the novel fungicide did not seem to provide any gains in this respect in comparison with the studied commercial bacterial fungicide. Compared with the studied chemical fungicide, although the novel one provided higher yields, the grain obtained had somewhat lower starch and lower gluten content; i.e., it possibly had somewhat lower quality. Although the novel consortium had a stimulating effect on some of the wheat growth and development characteristics (number of plants, stems and stems with ears per square meter), due to some reasons these did not translate into better grain yield and quality.

4.2. Wheat Yield, Grain Quality and Development Parameters as Related to the Different Modes of Application of the Novel Fungicide

The novel fungicide was tested under three treatments: seed-only treatment, seed-only treatment followed by one foliar application, and seed-only treatment followed by two foliar applications at a fortnightly interval. As no differences in the wheat grain yield, grain quality and development characteristics were revealed between the treatments, we conclude that foliar applications of the novel preparation did not provide any additional gains, at least under the conditions of the study.

4.3. Soil Microbiome in Wheat Rhizosphere Soil

As application of any chemical or biological agents can affect the soil microbiome, and there might be differences associated with different preparations used, we assessed fungal and bacterial assemblages by DNA metabarcoding under different fungicides and under different modes of novel fungicide application.

4.3.1. Soil Mycobiome

The Ascomycota phylum as the ultimate dominant of the soil mycobiome, comprising on average about 50% of the sequence reads, was not affected by the fungicides used. However, other dominant phyla, i.e., Zygomycota and Mucoromycota, were notably affected: Zygomycota increased markedly under both commercial fungicides, the increase under the novel fungicide being not statistically significant; Mucoromycota decreased significantly under both commercial and novel fungicides with foliar application. The finding that the Mucoromycota decrease was consistent with the yield increase strongly suggested that these fungi, known mostly as grain contaminants [27], rather than pathogens, have a negative affect on wheat [28], which was at least partially mitigated by the fungicides used. These findings indicate unequivocally that fungicide application affects the soil mycobiome already at the high taxonomic level, although at this level it is hardly possible to interpret the clear role of the novel fungicide in fighting pathogens and hence in benefiting plant development and growth and, eventually, grain yield.

The finding that Basidiomycota were decreased by both commercial fungicides does not seem surprising as the phylum is the ultimate dominant in the topsoil of undisturbed ecosystems [29,30] and can be sensitive to disturbances and stresses.

At the OTU level, these differences, revealed at the phylum level, translated to some differences as well. The major dominating OTU of R. arrhizus/Mucoromycota, which was significantly decreased by all fungicide treatments except for seed-only treatment with the novel fungicide, is a known pathogen; not only does it target diverse agricultural plants [31], but globally it is the most common cause of serious human diseases [32,33]. At the same time, some strains of R. arrhizus can exhibit notable phosphate-solubilizing rates, thus promoting plant growth [34], and can also mitigate the detrimental effects of drought stress [35]. Therefore, the unequivocal conclusion about the agronomical and ecological significance of the much lower relative abundance of R. arrhizus in the rhizosphere of wheat plants cannot be considered as a positive or a negative outcome of treatment with the studied fungicides.

The second-ranked fungal OTU in the study in terms of abundance, identified as a Gibberella sp., was shown by other researchers to be one of the major dominants in agricultural soil fungal communities alongside Mortierella, Talaromyces and Chaetomium [36], which were also among the dominants in our study. Here, Gibberella sp. was increased by 10% (as compared with the no-fungicide treatment) by the novel fungicide if applied on seeds followed by two foliar treatments during the growing season; this seems a rather random result, which cannot be unambiguously interpreted, as the genus contains pathogenic [37] and saprophytic members. Focusing specifically on the three different modes of novel fungicide application, one can conclude that different treatments had no effect at all on the OTU composition and structure of the rhizosphere soil mycobiome, in line with the absence of the effect of the novel fungicide application modes on wheat grain yield, quality, and wheat plant growth and development characteristics. PERMANOVA and ANOSIM results confirm the conclusion at all taxonomic levels.

Two of the dominant Mortierella OTUs increased their abundance only under chemical fungicide application; however, this result did not translate to an increase in grain yield or most of the grain quality characteristics, except for the slightly increased starch content. The finding that three Mortierella OTUs showed increased abundance in seed-only treatment by the novel fungicide, and that this increased abundance was not found in the treatments with seed-only application combined with one or two foliar ones, seems rather inconsistent and hence difficult to interpret. If all three treatments had shown increased Mortierella OTU abundance, one can suggest the latter as one of the main reasons for bigger grain yields in these fields, as nowadays Mortierella fungi are considered beneficial members of the agricultural soil mycobiome, protecting agricultural plants from pathogens [38].

4.3.2. Soil Bacteriobiome

The major (≥5% of the total number of sequence reads) bacterial dominants in the study, i.e., Pseudomonadota, Acidobacteriota, Bacteroidota, Actinomycetota and Verrucomicrobiota, were similar to the soil under wheat in another West Siberian region [39] and other regions [40] as well.

The Pseudomonadota phylum was increased by ca. 3% under the novel fungicide applied to seeds in combination with double foliar application, which was not caused by the fungicide itself, as its Raoultella ornithinolytica bacterium belonged to the Gammaproteobacteria class, the abundance of which was not affected by any fungicides.

The chemical fungicide decreased Bacteroidota (and its classes Chitinophagia and Cytophagia) and increased unclassified Bacteria abundance as compared with all other fungicides: the effect, being different from both bacterial fungicides used, suggests direct influence on Bacteroidota and some other as-yet-unidentified bacteria. Verrucomicrobiota and Chloroflexota were slightly increased by the chemical fertilizer, but only in comparison with the novel fungicide treatment involving one or two foliar applications: the finding is difficult to interpret, other than to relate it to the compositional nature of the relative abundance data.

At the family level, the difference between no-fungicide and fungicide treatments was observed only for the chemical fungicide: this finding allows us to conclude that the novel fungicide did not affect the dominant part of the rhizosphere soil bacteriobiome as compared with the no-fungicide treatment. At the OTU level, the differences in abundance of Bradyrhizobium sp. and some unclassified Spartobacteria_gis were observed only between two novel fungicide treatments, whereas other dominant OTUs (Sphingomonas sp. and Pseudarthrobacter sp.) showed a difference between the novel fungicide treatment and the no-fungicide one. The found differences, however, were less than one percent of the relative abundance of sequence reads, and therefore hardly seem to be of agronomical and ecological relevance. Overall, these findings allow us to conclude that treating wheat with the antifungal preparations did not significantly affect the wheat rhizosphere bacteriobiome.

4.3.3. General Considerations

Although application of a chemical fungicide resulted in a somewhat improved grain quality, there was no gain in yield, whereas application of bacterial fungicides, both commercial and novel, yielded on average 24% more grain. Whether the current wheat grain market prices in the country can compensate for the total cost of fungicide application, providing some profit, even in the case of the locally produced consortium, is a complicated issue beyond the aim of this article.

Prior to starting the experiment, the wheat seed infection rate with fungi was estimated; however, specific fungal species or toxins were not determined, including after the experiment. This may be regarded as a shortcoming of the study, preventing a more substantiated conclusion about the mechanism of the fungicidal action in the field, although the study was not aimed at elucidating the mechanism per se.

Since application of fungicides requires using their solutions or suspensions in water, the no-fungicide treatment should have been performed with similar treatments, but only with tap water, both for treating seeds and foliar application. Such treatment can influence the germination of seeds and further development of seedlings [41,42,43] and hence the rhizosphere microbiome as well.

None of the bacterial agents of the fungicides applied, i.e., Bacillus subtilis, R. ornithinolytica or P. allii, were found in the wheat rhizosphere soil at the time of sampling, i.e., wheat harvesting, although two unidentified Bacillus spp. OTUs and one Pantoea sp. OTU were detected. This implies that these bacteria did not persist around seeds and/or in the germisphere after application on seeds and did not reach and/or persist in the rhizosphere after foliar application. It may also imply rather quick action, within 1–3 days, of bacterial agents on fungi, i.e., similar in speed to the algicidal activity of Raoultella ornithinolytica [44]. As for P. allii, it could be an endophyte [45], and as such may be found in the rhizosphere; it also can have some plant-growth-promoting effect on plants [46], but commonly it is known as an allium pathogen [47]. An antifungal mechanism of the agents comprising the novel fungicide tested in this study should be investigated in detail.

5. Conclusions

The proposed preparation, representing a consortium of the Raoultella ornithinolytica strain and two strains of Pantoea allii, seems to have good prospects as a fungicide for wheat protection: its effect on grain yield of spring wheat, grown in the south of West Siberia, was found to be similar to that of the well-known commercial bacterial fungicide, based on a Bacillus subtilis strain. These two bacterial fungicides, as well as a chemical fungicide, also used in the study, all showed some effect on the microbiome diversity of the wheat rhizosphere soil, sampled at harvest. The changes in the mycobiome seemed more pronounced as compared with the changes in the bacteriobiome. Due to the low species/strain resolution of the DNA metabarcoding, the revealed shifts in the microbiome composition and structure can hardly be interpreted agronomically and environmentally. These aspects need more comprehensive and detailed investigation, using methodology with higher species resolution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P. and L.A.; methodology, M.K., N.F. and Y.S.; software, M.K.; validation, P.B.; formal analysis, M.K. and P.B.; investigation, N.F., O.B. and Y.S.; resources, M.K.; data curation, P.B. and N.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.P. and P.B.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and L.A.; visualization, O.B. and P.B.; supervision, M.K. and L.A.; project administration, A.P.; funding acquisition, M.K. and L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Projects No. FZSR-2024-0009 and No.125012300656-5). The 16S- and ITS-metabarcoding was performed as a part of project No. 125012300656-5.

Data Availability Statement

The sequence read data reported in this study were submitted to the NCBI Short Read Archive under bioproject accession number PRJNA1320511.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Natalia B. Naumova, Leading Researcher with the Laboratory of Agrochemistry in the Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Novosibirsk Russia), for her comments and advice on statistics and English language.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Skolotneva, E.S.; Leonova, I.N.; Bukatich, E.Y.; Salina, I.A. Methodical approaches to identification of effective wheat genes providing broad-spectrum resistance against fungal diseases. Vavilov J. Genet. Breeding 2017, 21, 862–869. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orina, A.S.; Gavrilova, O.P.; Gagkaeva, T.Y.; Gogina, N.N. Contamination of grain in West Siberia by Alternaria fungi and their mycotoxins. Plant Prot. News 2021, 4, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, S.; Bohn, M.; Rutkoski, J.; Butts-Wilmsmeyer, C.; Mideros, S.; Jamann, T. Comparative Review of Fusarium graminearum Infection in Maize and Wheat: Similarities in Resistance Mechanisms and Future Directions. Molecular plant-microbe interactions. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2025, 38, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asyakina, L.K.; Serazetdinova, Y.R.; Frolova, A.S.; Fotina, N.V.; Neverova, O.A.; Petrov, A.N. Antagonistic activity of extremophilic bacteria against phytopathogens in agricultural crops. Food Process. Tech. Technol. 2023, 53, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Russian Agricultural Centre for the Kemerovo Region. The survey of the Phytosanitary Status of Agricultural Crops in the Kemerovo Region in 2024 and the Forecast for the Development of Hazardous Objects in 2025. 2025. Available online: https://clck.ru/3PrCVP (accessed on 20 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Fotina, N.V.; Serazetdinova, Y.R.; Kolpakova, D.E.; Asyakina, L.K.; Atuchin, V.V.; Alotaibi, K.M.; Mudgal, G.; Pro-sekov, A.Y. Enhancement of wheat growth by plant growth-stimulating bacteria during phytopathogenic inhibition. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 60, 103294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.F.S.A.; Singh, E.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Schenk, P.M. Emerging microbial biocontrol strategies for plant pathogens. Plant Sci. 2018, 262, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Jia, C.; Jing, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, P.; He, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, L.; Zhao, E. Occurrence and dietary risk assessment of 37 pesticides in wheat fields in the suburbs of Beijing, China. Food Chem. 2021, 350, 129245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liao, Q.; Ling, W.; Waigi, M.G.; Odinga, E.S. Chlorpyrifos inhibits nitrogen fixation in rice-vegetated soil containing Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501. Chemosphere 2020, 256, 127098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serazetdinova, Y.; Chekushkina, D.; Borodina, E.; Kolpakova, D.; Minina, V.; Altshuler, O.; Asyakina, L. Synergistic interaction between Azotobacter and Pseudomonas bacteria in a growth-stimulating consortium. Foods Raw Mater. 2025, 13, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nysanth, N.S.; Divya, S.; Nair, C.B.; Anju, A.B.; Praveena, R.; Anith, K.N. Biological control of foot rot (Phytophthora capsici Leonian) disease in black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) with rhizospheric microorganisms. Rhizosphere 2022, 23, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.H.R.; Yusup, S.; Kueh, B.W. B Effectiveness of biopesticides in enhancing paddy growth for yield improvement. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2018, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.P.; Muratore, L.N.; Solé-Gil, A.; Farías, M.E.; Ferrando, A.; Blázquez, M.A.; Belfiore, C. Extremophilic bacteria restrict the growth of Macrophomina phaseolina by combined secretion of polyamines and lytic enzymes. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 32, e00674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asyakina, L.K.; Vorob’eva, E.E.; Proskuryakova, L.A.; Zharko, M.Y. Evaluating extremophilic microorganisms in industrial regions. Foods Raw Mater. 2023, 11, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asyakina, L.K.; Isachkova, O.A.; Kolpakova, D.E.; Borodina, E.E.; Boger, V.Y.; Prosekov, A.Y. The effect of a microbial consortium on spring barley growth and development in the Kemerovo region, Kuzbass. Grain Econ. Russ. 2024, 16, 104–112. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydromentcenter of Russia. Available online: https://meteoinfo.ru/climatcities?p=1935 (accessed on 26 October 2025). (In Russian).

- Fotina, N.V. The Search, Study of Properties and Practical Application of Rhizobacteria in Regulating the Biotic Stress of Wheat: Specialty 4.3. Ph.D. Thesis, Kemerovo State University, Kemerovo, Russia, 2025; 168p. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Serazetdinova, Y.R.; Borodina, E.E.; Fotina, N.V.; Naik, A.; Mudgal, G.; Asyakina, L.K. Rhizobia as complex biofertilizers for wheat: Biological nitrogen fixation and plant growth promotion. Foods Raw Mater. 2026, 14, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosstandart. Agricultural Seeds. Methods for Determination of Disease Infestation: GOST 12044-93; Federal Agency on Technical Regulating and Metrology: Moscow, Russia, 1995; 59p. [Google Scholar]

- Barillot, C.D.C.; Sarde, C.-O.; Bert, V.; Tarnaud, E.; Cochet, N. A standardized method for the sampling of rhizosphere and rhizoplane soil bacteria associated to a herbaceous root system. Ann. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlemann, D.P.; Labrenz, M.; Jurgens, K.; Bertilsson, S.; Waniek, J.J.; Andersson, A.F. Transitions in bacterial communities along the 2000 km salinity gradient of the Baltic Sea. ISME J. 2011, 5, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toju, H.; Tanabe, A.S.; Yamamoto, S.; Sato, H. High-coverage ITS primers for the DNA-based identification of ascomycetes and basidiomycetes in environmental samples. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naïve Bayesian Classifier for Rapid Assignment of rRNA Sequences into the New Bacterial Taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, O.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Education and Data Analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. Available online: http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Hughes, J.B.; Hellmann, J.J. The Application of Rarefaction Techniques to Molecular Inventories of Microbial Diversity. Methods Enzymol. 2005, 397, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minutillo, S.A.; Ruano-Rosa, D.; Abdelfattah, A.; Schena, L.; Malacrinò, A. The Fungal Microbiome of Wheat Flour Includes Potential Mycotoxin Producers. Foods 2022, 25, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriuchkova, L.O. Micromycetes associated with wheat diseases in different regions of Ukraine. Mikrobiol. Zhurnal 2013, 75, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Naumova, N.B.; Belanov, I.P.; Alikina, T.Y.; Kabilov, M.R. Undisturbed Soil Pedon under Birch Forest: Characterization of Microbiome in Genetic Horizons. Soil. Syst. 2021, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Huang, J.; Yu, H.; Tian, Y.; Rao, X.; Zhang, X. Do the Reclaimed Fungal Communities Succeed Toward the Original Structure in Eco-Fragile Regions of Coal Mining Disturbances? A Case Study in North China Loess-Aeolian Sand Area. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 770715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, J.; Yang, T.; Yang, R. Isolation and identification of Alternaria alstroemeriae causing postharvest black rot in citrus and its control using curcumin-loaded nanoliposomes. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1555774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiada, A.; Pavleas, I.; Drogari-Apiranthitou, M. Epidemiological Trends of Mucormycosis in Europe, Comparison with Other Continents. Mycopathologia 2024, 189, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghdam, Y.; Arghavan, B.; Kermani, F.; Jeddi, S.A.; Khojasteh, S.; Shokohi, T.; Aslani, N.; Ebrahimi, A.; Javidnia, J. A fatal post-COVID-19 sino-orbital mucormycosis in an adult patient with diabetes mellitus: A case report and review of the literature. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2025, 19, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbrik, B.; Reid, T.E.; Nkir, D.; Chaouki, H.; Aallam, Y.; Clark, I.M.; Mauchline, T.H.; Harris, J.; Pawlett, M.; Barakat, A.; et al. Unlocking the agro-physiological potential of wheat rhizoplane fungi under low P conditions using a niche-conserved consortium approach. J. Exp. Bot. 2025, 76, 2320–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, A.S.; Fathey, H.A.; Mohamed, A.H.; Ibrahim, A.A.; Abdel-Haleem, M. Mitigating drought stress and enhancing maize resistance through biopriming with Rhizopus arrhizus: Insights into Morpho-Biochemical and molecular adjustments. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, N.; Zhang, H.; Jia, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Feng, X.; Tang, B.; Zhao, B.; Liu, Y. Residual Dynamics of Chlorantraniliprole and Fludioxonil in Soil and Their Effects on the Microbiome. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Alfalahi, A.O.; Hassan, A.K.; Khalofah, A.; Mena, E.; Dababat, A.A.; Mokrini, F. Investigating the efficacy of bioactive compounds from selected plant extracts against Gibberella fujikuroi species complex associated with damping off disease in sweet corn. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, E.; Hanaka, A. Mortierella Species as the Plant Growth-Promoting Fungi Present in the Agricultural Soils. Agriculture 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumova, N.; Barsukov, P.; Baturina, O.; Rusalimova, O.; Kabilov, M. West-Siberian Chernozem: How Vegetation and Tillage Shape Its Bacteriobiome. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domnariu, H.; Trippe, K.M.; Botez, F.; Partal, E.; Postolache, C. Long-term impact of tillage on microbial communities of an Eastern European Chernozem. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karaki, G.N. Response of wheat barley during germination to seed osmopriming at different water potential. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 1998, 181, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mim, T.F.; Anwar, P.; Ahmed, M.; Sriti, N.; Moni, E.H.; Hasan, A.K.; Yeasmin, S. Competence of different priming agents for increasing seed germination, seedling growth and vigor of wheat. Fund. Appl. Agric. 2021, 6, 444–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaeim, H.; Kende, Z.; Jolánkai, M.; Kovács, G.P.; Gyuricza, C.; Tarnawa, Á. Impact of Temperature and Water on Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Maize (Zea mays L.). Agronomy 2022, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Kang, X.; Chu, L.; Wang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhao, X.; Cao, X. Algicidal mechanism of Raoultella ornithinolytica against Microcystis aeruginosa: Antioxidant response, photosynthetic system damage and microcystin degradation. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 287, 117644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, S.I.; Castro, P.M. Diversity and characterization of culturable bacterial endophytes from Zea mays and their potential as plant growth-promoting agents in metal-degraded soils. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 14110–14123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.M.H.; Vilas-Boas, Â.; Sousa, C.A.; Soares, H.M.V.M.; Soares, E.V. Comparison of five bacterial strains producing siderophores with ability to chelate iron under alkaline conditions. AMB Express 2019, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Shin, G.Y.; Stice, S.; Bown, J.L.; Coutinho, T.; Metcalf, W.W.; Gitaitis, R.; Kvitko, B.; Dutta, B. A Novel Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Across the Pantoea Species Complex Is Important for Pathogenicity in Onion. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2023, 36, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).