1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Transport systems are at the centre of current debates on climate change mitigation, energy security and territorial cohesion. To reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions while maintaining or improving regional accessibility, many countries are searching for alternatives to short- and medium-haul air travel and car-based mobility. High-speed rail (HSR) and other emerging forms of fast rail transport, such as magnetic levitation (Maglev) systems and the Hyperloop concept, are often presented as promising options in this context. These systems are not only engineering solutions: by changing travel times and perceived distances, they have the potential to reshape travel behaviour, influence location decisions of households and firms, and contribute to long-term structural changes in the economy [

1].

In Europe, and especially in Central and Eastern Europe, the discussion around HSR is particularly relevant. Only a limited number of fast rail lines are currently in operation in this part of the continent, yet several EU member states are considering the construction of new lines or the upgrading of existing ones within the framework of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T). Many of these projects are still at the stage of political declarations and strategic planning, but they already raise important questions about the potential environmental, economic and social impacts of introducing fast rail services in regions that are presently dominated by road transport and short-haul flights. For policymakers and planners, it is therefore essential to understand not only the technical characteristics of fast rail systems, but also their wider role within multi-modal transport networks [

2].

1.2. Objective of the Study

A substantial body of literature has examined the technical and operational aspects of HSR, as well as the financial performance of individual projects. Other studies focus on specific issues such as safety, service quality or passenger demand. However, there are fewer integrative reviews that look beyond the engineering dimension and synthesise evidence on the broader environmental, economic and social consequences of fast rail systems, while at the same time considering their position relative to competing modes such as air transport and private cars. The growing interest in Maglev and Hyperloop concepts further increases the need for an overview that places different fast rail technologies in a common impact-oriented framework rather than treating them as purely technological innovations.

The present paper aims to contribute to this discussion by providing a structured overview of fast rail transport with an explicit focus on wider impacts. Rather than offering a detailed technological review, the study concentrates on how HSR and related high-speed concepts interact with other modes of transport and with the territories they serve. Specifically, the paper pursues three objectives:

Summarise findings from the literature on the environmental, economic and social impacts of HSR, including aspects such as energy use and emissions, regional accessibility, land-use change and urban development.

Place HSR in a broader family of fast rail technologies by briefly outlining the main characteristics of Maglev and Hyperloop systems, with emphasis on those features that are relevant from an impact perspective; and

Compare HSR with air travel and private car use along selected dimensions—such as travel time, network integration and environmental performance—and to discuss the conditions under which HSR can realistically replace or complement these modes.

1.3. Research Approach

The analysis adopts a qualitative, literature-based approach. Academic publications and policy reports were collected from major scientific databases and institutional sources, with a focus on studies that report on the wider impacts of HSR and other fast rail technologies or compare them with air and road transport. These documents were reviewed to summarise key findings and to highlight typical advantages, limitations and contextual factors reported in the literature.

The technological descriptions included in the paper are therefore limited to the level necessary for understanding these impacts and for enabling a meaningful comparison between modes. The main emphasis is placed on the environmental, economic and social dimensions of fast rail development, while recognising that the concrete outcomes of individual projects depend on country-specific institutional, geographical and demand conditions that are also reflected in the reviewed studies.

2. Current and Planned Fast Trains Worldwide

2.1. Main Concepts of Fast Rail Transport

In this paper, the term fast rail transport is used as an umbrella concept that includes conventional steel-wheel HSR as well as emerging technologies such as Maglev systems and Hyperloop concepts. These systems share the common objective of providing very high commercial speeds and attractive door-to-door travel times on inter-urban corridors, but they differ significantly in terms of technical solutions, infrastructure requirements and maturity.

According to the widely used definition of the International Union of Railways (UIC), HSR services operate either on newly built lines designed for speeds of 250 km/h or more, or on upgraded conventional lines where speeds of at least 200 km/h can be reached. In practice, HSR systems combine upgraded or newly built infrastructure, high-performance rolling stock and advanced signalling and control systems to achieve operating speeds typically between 200 and 320 km/h. HSR is the most widely deployed form of fast rail transport today, with extensive networks in Europe and East Asia and selected lines in other world regions.

Maglev systems rely on electromagnetic forces to levitate and propel vehicles along dedicated guideways, eliminating direct wheel–rail contact. This allows for higher potential speeds and smoother rides but requires fully purpose-built infrastructure and specialised power and control systems. To date, only a small number of commercial or demonstration Maglev lines are in operation, and the technology remains at an early stage of large-scale deployment.

The Hyperloop concept combines low-pressure tubes with magnetically levitated or air-cushioned pods to achieve very high cruising speeds with low aerodynamic drag. Several companies and research consortia are investigating technical feasibility, safety and regulatory issues, and various test tracks have been constructed. However, no full-scale operational Hyperloop corridor exists yet, and key aspects such as costs, capacity, safety standards and long-term demand remain highly uncertain.

Against this background, the remainder of the paper focuses primarily on conventional HSR, which currently represents the dominant and most mature form of fast rail transport. Maglev and Hyperloop are treated as emerging technologies that may, under certain conditions, complement or compete with HSR in the future; their potential impacts are briefly revisited in

Section 4.5.

2.2. Global Distribution of HSR Networks

HSR networks have primarily been developed in the world’s most advanced regions, most notably in East Asia and Europe. The development and operation of such systems are highly capital- and knowledge-intensive: they require substantial upfront investment, complex infrastructure and specialised operational expertise. As a result, only countries with sufficient financial resources, institutional capacity and technical know-how have been able to build extensive HSR networks so far [

3].

At the same time, an increasing number of developing and emerging economies have placed HSR projects on their transport policy agenda. In these contexts, HSR investments are often framed as instruments to stimulate economic growth, promote regional convergence and enhance global competitiveness. The global pattern of HSR deployment therefore reflects both existing economic hierarchies and the aspirations of latecomer countries seeking to reposition themselves within international production and mobility systems [

4].

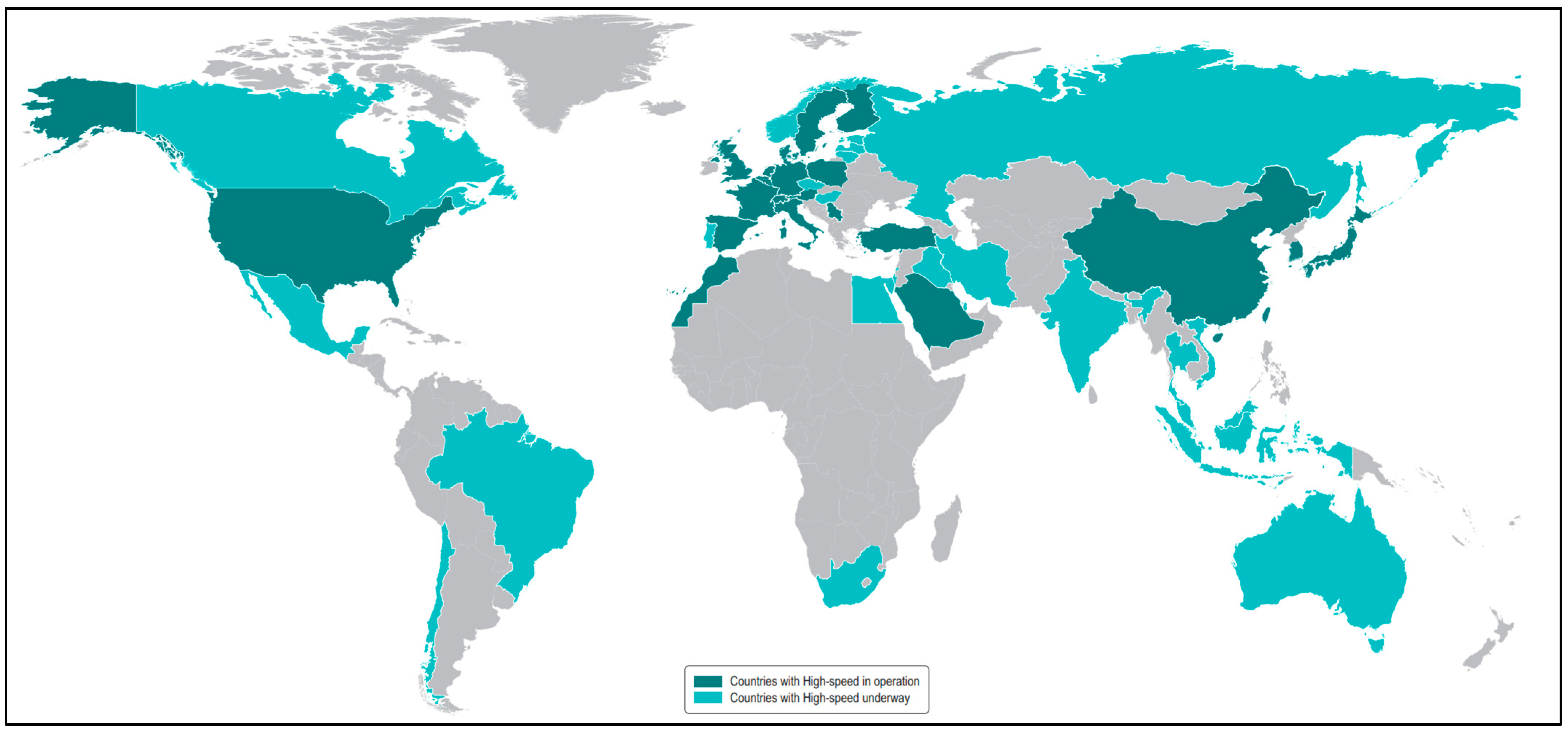

From a geographical perspective, the largest concentration of HSR lines is found in East Asia—with China and Japan as the two main actors—followed by Europe, where several countries operate dense high-speed networks (

Figure 1). In contrast, HSR remains absent or limited in many parts of the world, including large areas of Africa, South America and North America. The global map of existing and planned HSR corridors thus reveals a highly uneven distribution of fast rail technologies, which has important implications for accessibility and the spatial organisation of economic activities [

5].

2.3. Historical Evolution of HSR Networks (1964–2022)

The modern era of HSR began in Japan in 1964, the year of the Tokyo Olympic Games, with the opening of the Tokaido Shinkansen between Tokyo and Osaka. This line demonstrated that rail could once again become a fast, reliable and competitive option for inter-city travel on busy corridors, and it served as an international reference point for later projects.

In Europe, the first HSR service started in 1977 in Italy, followed by the opening of the French TGV network in the early 1980s. During the subsequent decades, Germany, Spain and other countries joined the group of HSR operators. Initially, investments focused on a limited number of flagship routes linking capital cities or major economic centres. Over time, these lines were extended and interconnected, and the network gradually evolved from isolated segments into larger, nationally integrated systems.

A major turning point in the global diffusion of HSR occurred in the 2000s, when China launched an ambitious, state-led programme for the development of a nationwide high-speed network. Within a relatively short period, the country constructed tens of thousands of kilometres of HSR lines, fundamentally transforming the global distribution of fast rail infrastructure. Since then, new countries have continuously joined the group of HSR operators, and existing systems have been expanded into extensive networks [

4].

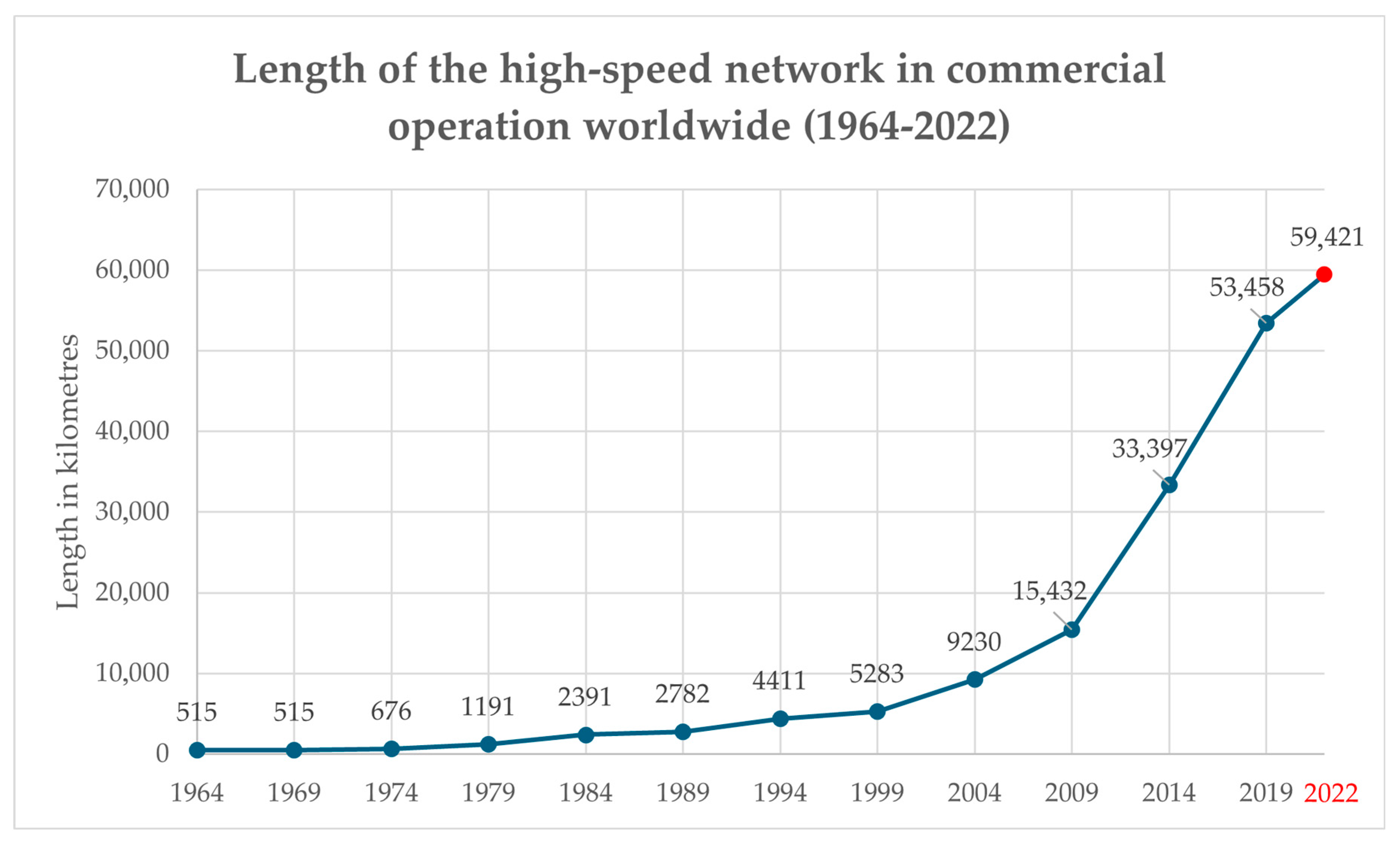

The cumulative length of HSR lines worldwide has therefore followed an increasingly steep growth trajectory (

Figure 2). After a relatively slow initial phase dominated by Japan and a few European pioneers, the global expansion of HSR networks began to accelerate in the 1990s and 2000s, and especially after the large-scale Chinese investments of the last two decades. This dynamic evolution underlines that HSR is not a static technology, but one that has been adapted to diverse institutional, geographical and demand conditions [

6].

2.4. HSR in Europe

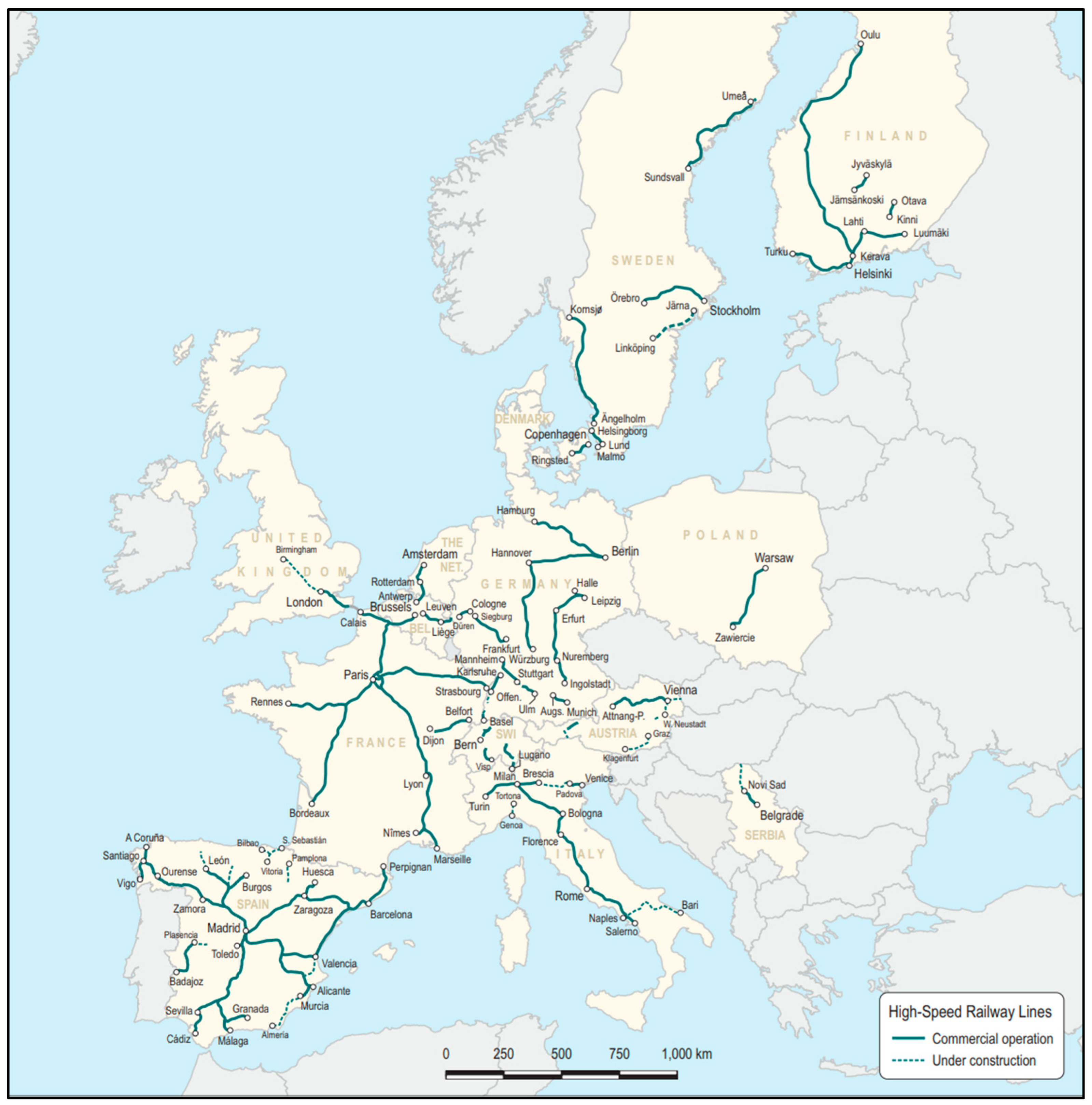

In Europe, HSR infrastructure is concentrated mainly in Western and Southern Europe. France, Spain, Italy and Germany form the core of the network, complemented by high-speed lines in Belgium, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Austria and Switzerland. Spain currently operates the longest HSR network in Europe, while the total length of high-speed lines on the continent now exceeds 12,000 km (

Figure 3). This network connects many of the continent’s largest metropolitan regions and offers a competitive alternative to short- and medium-haul air travel on several major corridors [

7].

As the core national networks have matured, attention has increasingly shifted towards cross-border connections and the integration of national systems into a more coherent European network. Examples include the Paris–Brussels–Amsterdam–London axis, high-speed links between France and Germany, or cross-border services between France and Spain. These international connections are crucial for realising the full potential of HSR as part of a European-wide long-distance passenger transport system.

At the same time, the spatial coverage of HSR within Europe remains uneven. Western European countries generally have denser networks and higher frequencies, whereas in Central and Eastern Europe HSR lines are scarce or still at the planning or upgrading stage. Flagship projects such as Rail Baltica, which will connect the Baltic states to the standard-gauge European network, and the modernisation of the Budapest–Belgrade corridor illustrate how the HSR concept is gradually extending eastwards. These investments raise important questions about how HSR can reshape regional accessibility, support cohesion objectives and interact with existing road- and air-based mobility patterns.

At EU level, the HSR agenda is closely linked to the TEN-T policy and to recent initiatives under the European Green Deal. Policy documents envisage a substantial expansion of the HSR network and the creation of a continuous, interoperable system linking EU capitals and major cities, with the dual aim of improving connectivity and shifting passenger demand from air and road to rail. Recent research has also proposed future European HSR network designs and used passenger demand forecasting to test whether specific network concepts could meet or exceed these policy targets [

8].

2.5. HSR in China

China today operates the world’s largest HSR network. The development of this network gained momentum in the early 2000s, when the national government designated rail transport as a strategic priority sector within a broader programme of infrastructure-led development. In the initial phase, Chinese railway companies largely relied on foreign technology and rolling stock, purchasing trains and systems from European and Japanese manufacturers—including licensed versions of German, French and Japanese high-speed trains—and adapting them to domestic conditions.

Following this period of technology transfer, China increasingly shifted towards domestically designed HSR trains and infrastructure. At the same time, the government launched an ambitious nationwide network development plan aimed at creating a system of radial and grid-like corridors linking major cities and regions. Supported by rapid urbanisation, strong economic growth, massive domestic travel demand and powerful state coordination, the Chinese HSR network expanded at an exceptional pace [

5].

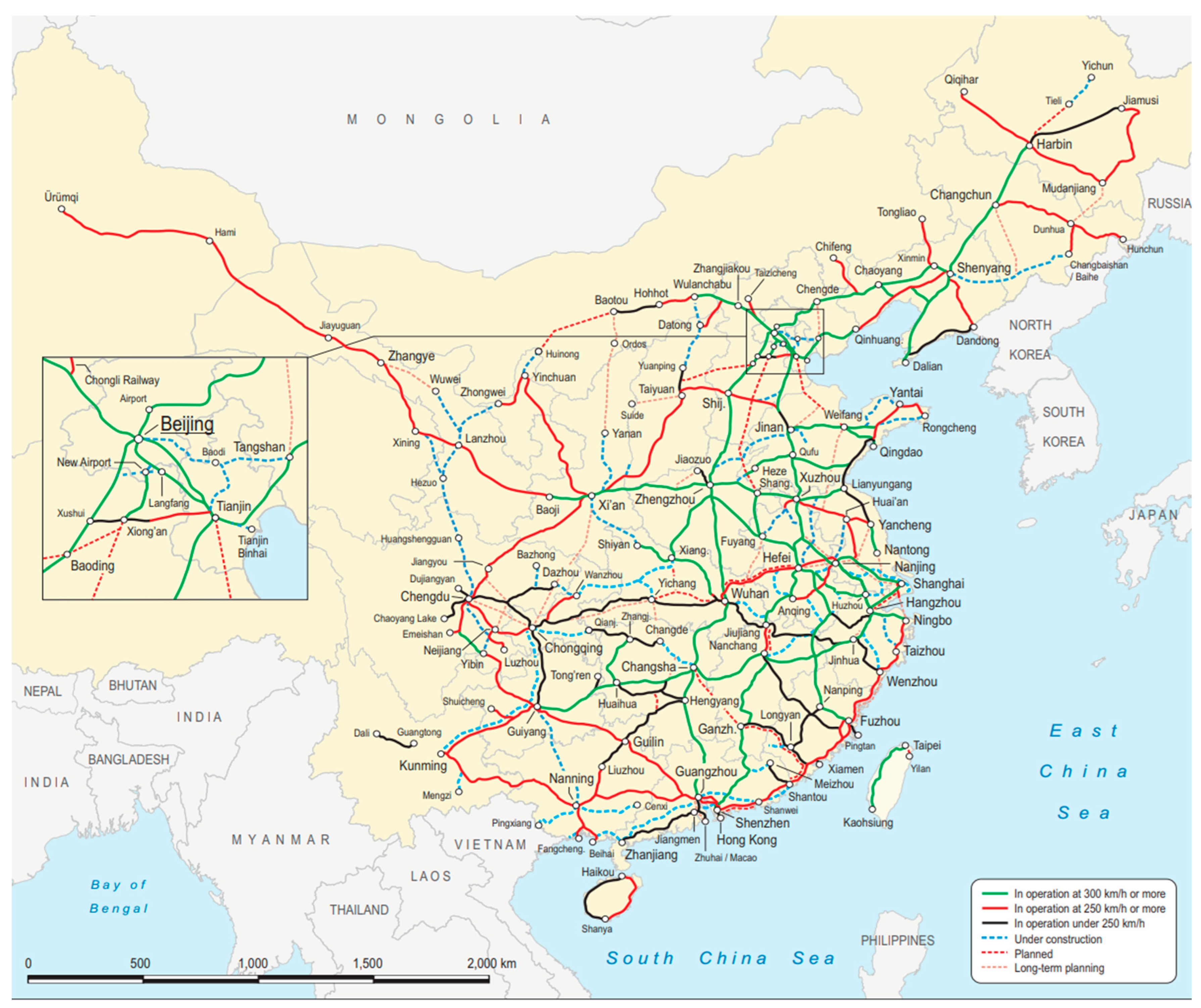

Today, China has constructed more than 40,000 km of high-speed lines, connected the country’s key economic regions and substantially reduced travel times between major cities (

Figure 4). HSR has become a highly competitive alternative to domestic air transport on many routes, and in some corridors, it has captured a dominant share of long-distance passenger traffic. Around many HSR stations, new urban development zones and business districts have emerged, and accessibility improvements have contributed to changes in the spatial distribution of economic activity [

9].

The Chinese experience illustrates how HSR can be used as a tool of state-led development, combining industrial policy, infrastructure investment and regional development objectives. At the same time, it has generated debates about long-term financial sustainability, demand risks and the distribution of benefits between core metropolitan regions and more peripheral areas. These issues are directly relevant to the impact-oriented perspective adopted in this paper and will be revisited in later sections.

2.6. Summary and Implications for Later Analysis

The global experience with HSR shows that fast rail systems emerge and evolve under specific economic, institutional and territorial conditions. East Asia and Europe have so far been the main laboratories of HSR development, while a growing number of other countries are experimenting with or planning their own networks. The strong concentration of HSR in a limited number of world regions, the temporal dynamics of network expansion since the 1960s, and the contrasting European and Chinese development models all provide important context for understanding the potential role of fast rail in future transport systems.

These patterns underline why it is essential to examine not only the technical features of HSR, but also its environmental, economic and social impacts in different settings. The subsequent sections of this paper therefore draw on the international evidence summarised above to compare fast rail with competing modes of transport and to explore the conditions under which HSR and related systems can contribute to more sustainable and balanced mobility [

3].

In general, the countries with the largest HSR networks are also the pioneers in HSR development. In contrast, countries that joined the HSR expansion later—often with smaller networks—tend to adopt ready-made technology packages. These typically include [

6]:

design and construction of tracks and rail infrastructure.

procurement of high-speed rolling stock.

training of personnel required for operations.

implementation of modern control and signalling systems, which are essential due to the increased operating speeds.

The following subsection provides a concise overview of the most prominent HSR countries, based on their technological and economic significance.

4. Environmental, Economic and Social Impacts of HSR

4.1. Environmental Performance in a Life-Cycle Perspective

HSR is frequently presented as a low-carbon alternative to short- and medium-haul air travel and car-based mobility. However, recent research has emphasised that the environmental performance of HSR can only be properly understood in a full life-cycle perspective. LCA studies show that infrastructure construction and maintenance generate substantial GHG emissions and other environmental burdens, in some cases comparable to or even exceeding the operational phase over the lifetime of a line [

16].

Infrastructure-related impacts are largely driven by energy- and material-intensive components such as earthworks, bridges, tunnels, tracks and stations. Steel production for rails and reinforcement, as well as cement and concrete for civil structures, are among the dominant contributors to embodied emissions. At the same time, the use phase can achieve very low specific emissions per passenger-kilometre when trains run with high load factors and draw electricity from decarbonised power systems [

17].

Several corridor and network-level case studies highlight the importance of demand density and occupancy. On high-demand routes where HSR attracts passengers from aviation and private car use, and where trains operate with high seat utilisation, net GHG savings over the life cycle are achievable even after accounting for construction and maintenance. Conversely, on low-demand corridors the embodied impacts of building and maintaining dedicated high-speed lines may not be compensated by operational savings within the evaluation period, especially if modal shift from air and car remains limited [

18].

The power generation mix is another critical factor. Where HSR relies on electricity systems with a high share of fossil fuels, the climate advantage over aviation and road can be significantly reduced, particularly in the early years of operation. As national grids decarbonise, the relative performance of HSR improves, which suggests that synchronising major HSR investments with broader energy transition policies is essential for maximising environmental benefits [

19].

More recent LCAs have started to explore additional impact categories beyond climate change, such as particulate matter formation, land use, resource depletion and noise. These studies underline that HSR is not impact-free: land take, habitat fragmentation, construction-related air pollution and resource use can be substantial and may be spatially concentrated along sensitive corridors. At the same time, by reducing car and short-haul air traffic, HSR can contribute to lower local air pollution and noise exposure near airports and congested highways. From a policy perspective, this reinforces the need for careful corridor selection, integration with existing rail infrastructure where feasible, and design choices that minimise embodied impacts while preserving high operational efficiency.

4.2. Economic Impacts and Regional Development

The deployment of HSR lines can generate a wide range of economic effects, from direct impacts on the transport sector to broader changes in regional development patterns. At the most immediate level, HSR reduces generalised travel costs (time and, in some cases, monetary costs) between connected cities, thereby increasing effective accessibility. Improved accessibility can foster more frequent business travel, labour market integration and tourism flows, which in turn may raise productivity and local demand. Ex post evaluations in countries with mature HSR networks, such as Italy and Spain, have found measurable increases in GDP, employment and firm performance in cities that gained HSR access, although the magnitude and spatial distribution of these effects vary considerably [

3].

Beyond these first-round effects, HSR can influence the spatial organisation of economic activity through agglomeration mechanisms. Faster and more reliable connections can strengthen linkages within existing urban networks, supporting the concentration of high-value services, knowledge-intensive industries and corporate headquarters in major hubs. Case studies in Europe and Asia show that some HSR corridors have contributed to the growth of intermediate cities by improving their connectivity to metropolitan cores, while others have mainly reinforced the dominance of already-strong centres. This suggests that HSR tends to amplify existing spatial economic structures rather than transform them entirely, and that complementary regional policies are crucial if more balanced development is desired [

2].

Furthermore, HSR investments often trigger changes in land and real estate markets. Improved accessibility can lead to rising property values around stations, especially where urban regeneration and transit-oriented development are pursued in parallel. For local authorities, this may create new opportunities for value capture mechanisms to co-finance infrastructure, but it can also exacerbate issues of affordability and displacement if not carefully managed. Meanwhile, peripheral regions bypassed by HSR corridors may experience relative disadvantages as economic activities and skilled labour concentrate along the high-speed axis [

20].

Recent work has also examined the distribution of economic benefits between urban and rural areas, and between different sectors. Difference-in-differences and computable general equilibrium models have been used to identify how HSR affects regional inequalities, firm productivity and sectoral structure. These studies generally indicate that HSR can support higher economic growth in connected regions, but they also warn of potential divergence between core and peripheral areas if connectivity improvements are uneven or not accompanied by complementary investments in secondary networks and human capital. Thus, HSR should be viewed as one element within a broader development strategy rather than a standalone lever for regional convergence.

4.3. Social and Territorial Equity Implications

While economic evaluations of HSR have traditionally focused on aggregate efficiency, there is growing recognition that equity and inclusion are central to the sustainability of HSR investments. Territorial equity concerns arise because not all regions or cities receive HSR stations, and even among those that do, service frequency and connectivity may differ considerably. This raises the question of whether HSR contributes to more balanced territorial development or reinforces existing spatial inequalities. Accessibility-based approaches have been proposed to quantify “winners and losers” in terms of changes in travel times and opportunities, often using indicators such as Gini coefficients, spatial equity indices and variation in accessibility distributions [

21].

At the social level, HSR services are typically priced above conventional rail, which may limit their use among low-income groups. Stated-preference and mode-choice studies show that income, car ownership and residence location strongly influence the probability of using HSR. In several contexts, users from wealthier backgrounds and large metropolitan areas are over-represented among HSR passengers, while residents of smaller cities and rural regions perceive the system as less accessible or even exclusive. This pattern can be partially mitigated by offering discounted fares, integrated ticketing and good connections to regional and local transport, but it underscores the need to explicitly incorporate social inclusion into HSR planning and evaluation frameworks [

2].

Equity issues also intersect with land-use change and housing markets around HSR stations. Upgrading station areas and surrounding neighbourhoods may improve urban quality and amenities, yet it can also trigger gentrification pressures, especially in centrally located districts. Without appropriate safeguards, long-term residents and lower-income households’ risk being priced out of newly attractive areas, while the benefits of improved accessibility accrue mainly to new residents and investors. This highlights the importance of pairing HSR projects with inclusive urban development policies, such as affordable housing quotas, protections for tenants and small businesses, and participatory planning processes.

The emerging literature suggests that HSR, by itself, does not guarantee either social justice or territorial cohesion. To move beyond purely efficiency-oriented cost–benefit analyses, several authors argue for multidimensional appraisal frameworks that integrate distributional effects, accessibility changes and social exclusion risks. In practice, this may require setting explicit equity objectives for HSR programmes, monitoring their distributional outcomes over time, and adjusting service design, pricing and complementary policies accordingly.

4.4. Synthesis and Policy Implications

Taken together, the environmental, economic and social evidence points to a nuanced picture of HSR. Under favourable conditions—sufficient demand density, high occupancy, a decarbonising power system and strong integration with conventional rail and public transport—HSR can deliver significant life cycle GHG savings and contribute to more efficient, productive and connected regional economies. Under less favourable conditions—low-demand corridors, fragmented networks, fossil-intensive electricity and poor first- and last-mile connectivity—HSR may underperform both environmentally and economically, while also exacerbating spatial and social inequalities [

22].

In addition to corridor- and network-level indicators, a stylised comparison of HSR, aviation and passenger cars along selected dimensions is presented in

Table 1. It illustrates that HSR combines relatively high commercial speeds, low specific CO

2 emissions and high passenger capacity, while aviation remains dominant for very long distances and passenger cars offer the highest flexibility but at the cost of higher emissions per passenger-kilometre and lower safety. This reinforces the idea that HSR is particularly well suited for medium-distance, high-demand corridors linking major urban centres, where it can attract substantial market share from both air and car travel (

Table 1).

From a policy perspective, these findings imply that decisions about HSR deployment should not be based solely on aggregate travel time savings or idealised assumptions about demand. Instead, comprehensive appraisal frameworks are needed that combine life-cycle environmental assessment with dynamic economic modelling and explicit distributional analysis. Such frameworks can help identify corridors where HSR is likely to generate robust net benefits, as well as those where alternative investments—such as upgrading conventional rail, improving regional services or enhancing digital connectivity—might deliver greater social returns.

Moreover, the design of HSR systems matters as much as the decision to build them. Service patterns, fare structures, station locations and integration with local transport all influence who benefits from high-speed connections and to what extent. Policies aimed at promoting inclusive, transit-oriented development around stations; ensuring affordable access for different income groups; and coordinating HSR expansion with wider decarbonisation and regional development strategies are critical to realising the full potential of HSR as part of a sustainable transport system.

4.5. Emerging Fast Rail Technologies: Maglev and Hyperloop

In addition to conventional wheel-on-rail high-speed systems, a growing body of literature discusses the potential role of Maglev and Hyperloop concepts as alternative forms of ultra-high-speed ground transport. From a technological perspective, both Maglev and Hyperloop promise higher cruising speeds and smoother rides than conventional HSR, but they require fully dedicated infrastructure and currently entail higher technological and financial risks.

Existing empirical evidence on the impacts of Maglev mainly comes from a small number of commercial or demonstration lines. These studies suggest that Maglev can achieve energy use and direct CO2 emissions per passenger-kilometre that are comparable to, or in some cases lower than, those of HSR when powered by low-carbon electricity. However, the need for purpose-built guideways and complex power and control systems can increase capital costs and embodied environmental impacts, so the overall performance strongly depends on demand density, network design and long-term utilization.

For Hyperloop, the evidence base is even more limited and largely relies on prospective life-cycle assessments and scenario-based socio-economic analyses. These indicate that, under optimistic assumptions, Hyperloop could offer substantial reductions in travel time and operational emissions compared with short-haul aviation. At the same time, infrastructure requirements, safety standards, regulatory frameworks and long-term demand remain highly uncertain, and there is yet no full-scale commercial corridor in operation. As a result, most authors emphasise that Hyperloop should currently be treated as an emerging option whose potential environmental, economic and social impacts need further empirical investigation, rather than as an immediate substitute for HSR.

From the perspective of this paper, Maglev and Hyperloop are therefore considered as complementary or longer-term alternatives to HSR. Their future role will depend on technological progress, regulatory developments and the evolution of demand on key inter-urban corridors. For the time being, conventional HSR remains the dominant and most mature form of fast rail transport, while Maglev and Hyperloop primarily serve as reference points for exploring possible future extensions of high-speed ground transport systems.

5. Conclusions

This paper set out to achieve three interrelated objectives: to summarise the environmental, economic and social impacts of HSR; to position HSR within a wider family of fast rail technologies; and to compare HSR with competing modes such as air transport and private cars. Drawing on the international literature, the review shows that HSR can substantially reduce life-cycle energy use and GHG emissions per passenger-kilometre relative to short- and medium-haul aviation and conventional car travel, if it operates on medium-distance, high-demand corridors, with high load factors and a decarbonising electricity mix. At the same time, HSR investments reshape regional accessibility patterns, influence land-use change and urban development around stations and can reinforce existing spatial inequalities if not accompanied by appropriate complementary policies.

The synthesis of economic and social evidence indicates that HSR can support productivity growth, labour market integration and tourism in connected cities, but that these benefits are unevenly distributed across regions and social groups. Rising property values and development pressures in HSR station areas may create opportunities for value capture, yet they also raise concerns about affordability and displacement. In modal comparison terms, HSR emerges as a strong competitor to air travel on many 300–800 km corridors and as an alternative to car travel where city-centre accessibility and network integration with conventional rail and public transport are good; outside these conditions, aviation and cars are likely to remain dominant.

Finally, by briefly examining Maglev and Hyperloop, the paper places HSR within a broader set of fast rail technologies. While Maglev and Hyperloop promise even higher speeds and potentially low operational emissions, their infrastructure requirements, costs, safety standards and long-term demand are still highly uncertain. For the foreseeable future, conventional HSR remains the most mature and widely deployed option. Policymakers should therefore treat HSR as a central element of strategies for decarbonising inter-urban mobility, while carefully assessing context-specific conditions and distributional effects, and keeping emerging fast rail technologies under critical, evidence-based review.