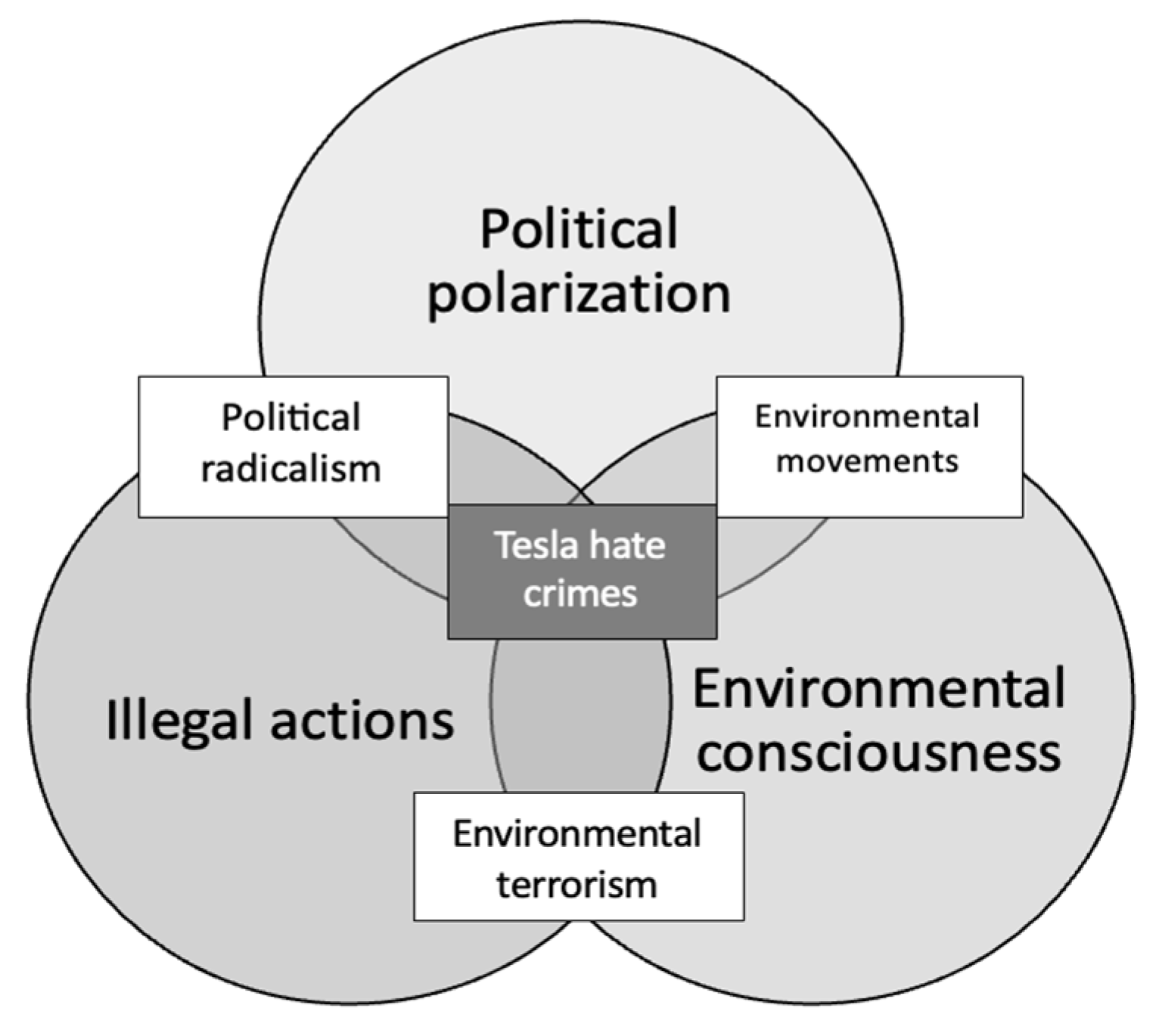

3.1. Polarization and Hate Crime as Social Psychological Phenomena

Social psychology is the science of understanding how individuals form group identities, develop attitudes about social hierarchy, perceive threats from other groups, and sometimes engage in targeted aggression.

Someone’s sense of self is not just based on their individual personality but also on the social groups to which they belong. We categorize ourselves as “in-group” members and others as “out-group”. Part of our social identity is in-group favoritism and out-group derogation, even in the absence of any direct conflict or competition [

13]. But when it comes to politics, it is not only the question of disagreements over some policy issues but a deeper process rooted in human identity, cognition, morality, and emotion—sometimes the group identity becomes more important than the issues themselves [

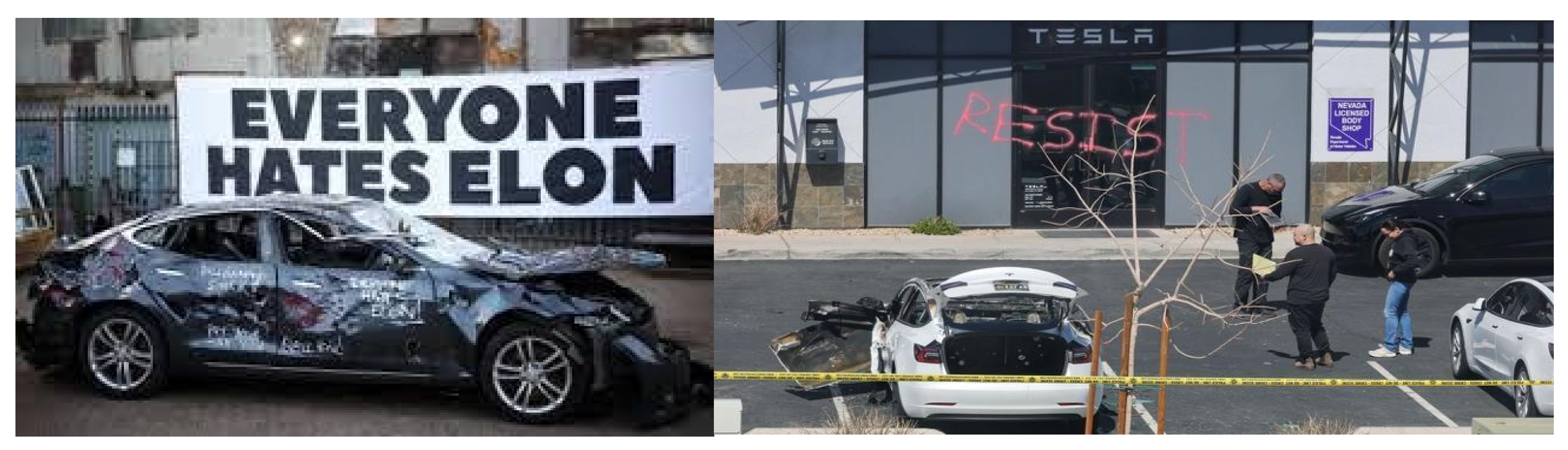

11]. When people are prevented from achieving a goal (let it be political, economic, or moral), they experience frustration, which builds up aggressive energy. If the source of the frustration is too powerful, ambiguous, or inaccessible to retaliate against (as Elon Musk has been seen in the Oval Office for a couple of months), the aggression is displaced into a more convenient and weaker target—his company’s products. This target is called the “scapegoat” in the literature [

14]. Scapegoating in the social psychology literature involves blaming a vulnerable, typically minority, out-group for problems they did not cause. In our case, the frustration caused by the political maneuvers of Elon Musk has been channeled to non-defending objects, like cars, e-chargers, and shops. Their demolition provided a simple solution for a complex problem (also known as public administration and federal budget) and an outlet for pent-up frustration.

In modern politics, abstract systems or inaccessible figures (like a president, a CEO, or a policeman) evoke frustration, leading individuals to attack symbolic stand-ins such as corporate or public property [

15]. As Tedeschi and Felson [

16] explain, vandalizing politically charged objects becomes a form of expressive aggression, allowing the perpetrator to communicate dissent or reclaim control. This kind of behavior often arises when people feel powerless within an existing system, whereby symbolic violence can be interpreted as a power move against the oppressor.

Another important factor of object-directed aggression is moral disengagement. Individuals cognitively justify these harmful acts by minimizing their consequences or blaming the victim. In our research focus, damage to a car or charger may not be seen as real harm for the perpetrator [

17,

18], who almost interprets their actions as socially acceptable or morally neutral.

3.2. Legal Assessment of the “Tesla Takedown” Incidents

“The so-called ‘Tesla Takedown’ is domestic terrorism, and my team is taking it on front and center,” said U.S. Attorney Edward R. Martin Jr. to the press after an individual, charged with four counts of vandalism against Tesla vehicles, appeared in court in April 2025 [

19]. Violence against Tesla dealerships will be labeled domestic terrorism, and perpetrators will “go through hell,” U.S. President Donald Trump said a month earlier in a show of support for the electric carmaker’s chief, Elon Musk [

20].

These statements indicate the high emotions around Tesla vandalism after the political character of such actions and the quick reactions of the U.S. political elite pushed these incidents into the limelight. The politicians were quick to label these acts as hate crimes and domestic terrorism, whereas supporters of the broader anti-capitalism and anti-fascism movements suggested that these actions may be viewed as a political display of opinion, basically a radical form of protected political speech, not unlike flag burnings during protest rallies. The actual charges raised against the perpetrators, however, tell a different story. Therefore, this paper seeks to explore some conflicting theories on the possible legal assessment of vandalizing Tesla vehicles and dealerships.

We point out five possible directions where the legal assessment of these actions can conclude. Firstly, the most basic assessment is property crime, not taking into consideration any political connotations or motivations of hate in the action. A subcategory of property crime reflects the motive behind the incidents. We examine whether these actions can be considered hate crimes. Next, we examine whether the political statements were right and whether domestic terrorism can be established. We also look at harassment as a possible legal assessment. Finally, we examine the other end of the spectrum, arguing whether defacing Tesla vehicles is a form of political protest or civil unrest protected by freedom of expression, comparable to the taking down of monuments by the Floyd/Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. In our assessment, we will mainly rely on the case and statutory law of the United States, since most of the Tesla vandalism cases occurred there.

3.2.1. Property Crime

Property crime in U.S. law refers to a descriptive criminological and legal category term that typically encompasses crimes against property (rather than persons), such as theft, burglary, vandalism, arson, destruction of property, etc. Although the actual legislation may differ from state to state, § 220 of the Model Penal Code [

21] includes arson, criminal mischief, and other property destruction (such as vandalism) in this category. The definitional criteria for property crimes involve the intentional destruction of or damage to the property of another person without permission. The conduct does not necessarily involve force or threat of force against a person [

22]; the primary victim is property rather than a person’s body. The mens rea (mental state) required is typically “knowingly” or “maliciously”, although this may vary depending on the jurisdiction. The motive (e.g., a political motive or racial bias) is legally irrelevant in the prosecution of such crimes.

This is the easiest legal assessment to conclude. Property has been damaged in an unlawful manner (i.e., without the consent of the owner), and the amount of this damage can be quantified in financial terms. The Tesla takedown actions—if no other factors are considered—clearly fit this definition. If we take away any political connotations, this is the easiest and legally clearest conclusion any court can arrive at.

The arrests and criminal charges made in relation to Tesla vandalism incidents also point in this direction, as the following examples show. A 33-year-old man was caught vandalizing several of the vehicles in downtown Minneapolis. Despite a formal recommendation from police, the Hennepin County Attorney’s Office has opted for a pre-charge diversion. The perpetrator will not face criminal charges, but he must repay the owners of all the damaged Teslas an approximate total of USD 20,000 in damages [

23]. On the other hand, the law is not so lenient towards individuals who choose to use more destructive methods or weapons in vandalism incidents. Nineteen-year-old Owen McIntire is facing federal charges of up to 30 years of jail time after allegedly driving to a Tesla dealership in Kansas City and throwing two Molotov cocktails at a Cybertruck, causing a fire and thousands of dollars in damage after the blaze spread to a second Cybertruck. He is charged with one count of unlawful possession of an unregistered destructive device and one count of malicious damage by fire of any property used in interstate commerce [

24].

3.2.2. Hate Crime

Although there is no federal hate crime statute [

25], in the United States, a hate crime (also called bias-motivated crime) is distinguished by the underlying motive of hatred or bias against someone based on a protected characteristic, such as race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, and transgender identity [

26]. A hate crime is defined by the confluence of an underlying criminal act (such as assault, harassment, vandalism) plus a bias motivation (protected characteristic of the victim). Property crimes like vandalism can be classified as hate crimes if committed with a discriminatory motive. The most important element from the above detailed definition is the fact that the action is directed against a certain social group, minority, ethnic group, sexual orientation, gender, etc. The U.S. Supreme Court in

Wisconsin v. Mitchell (508 U.S. 476 (1993)) affirmed the constitutionality of hate crime laws, holding that they do not punish protected thought or speech but rather the conduct of discriminatory victim selection. The law punishes the act motivated by bias, recognizing it as a distinct and greater harm.

In the case of the vandalism of Tesla cars and dealerships, this is the criterion where the definition loses its standing ground. That is because the targeted social group cannot be identified, since Tesla owners belong to a wide variety of ethnic groups, social statuses, genders, and probably different political identities. This is especially the case in instances of Tesla vandalism happening outside of the U.S. Foreign car owners cannot even be accused of being the voters of either American political party or supporters of President Trump. Also, the perpetrators of these actions do not even know the owner of the car personally, and thus, they cannot be sure whether the owner belongs to any particular social or political group. It can be stated that the Tesla vandalisms target the car itself, and not the owners of the car. Therefore, they cannot be considered a hate crime because they are not directed against a person or group but rather against an inanimate object. This assessment is supported by the fact that only a very few of the Tesla vandalism cases were prosecuted as hate crime incidents, and these ones also included an extra bias element. In California (Los Angeles County), a person was charged with felony vandalism and attempted hate crimes after he spray painted swastikas on more than a dozen cars (see People v. Robert Haymore (charging), 2025); in New York City (Brooklyn), the NYPD Hate Crimes Task Force arrested a suspect who allegedly left a brick marked with a swastika and “Nazi” on a Tesla Cybertruck outside a yeshiva, and the person was charged with criminal mischief and aggravated harassment as hate crimes (People v. Natasha Cohen (charging), 2025).

In a short intermezzo, we should point out that if the intention of the perpetrators of these acts was to intimidate Trump supporters, it is utterly misdirected. According to the Pew Research Center, Democrats have a much more positive impression of electric vehicles than Republicans, and 69% of Democrats say they are better for the environment as opposed to only 24% of Republican voters. Also, 58% of Democrats said they would consider buying electric vehicles, whereas only 30% of Republicans gave this answer [

27]. It is the general opinion that Democratic Party voters tend to be more concerned about the environment, and in an attempt to reduce carbon emissions, they are more likely to end up driving an electric car, such as a Tesla vehicle. So, if the perpetrators of Tesla vandalism wanted to send a message to Trump supporters or Republicans in general, they are more than likely to have misdirected their actions, drawing “friendly fire” on people in their own political group.

Based on the factors detailed above, our position is that describing the Tesla vandalism cases as a hate crime falls short of fulfilling the required criteria of its definition.

3.2.3. Domestic Terrorism

Next, we should examine whether these actions can be considered domestic terrorism, just like U.S. Attorney Martin and President Trump put it in the statements quoted above. Domestic terrorism is a unique legal category. Crucially, it is not a standalone criminal charge in the federal system. Instead, it is a definitional statute that provides investigatory authority and triggers severe sentencing enhancements for other underlying crimes (e.g., arson, conspiracy, destruction of property). The FBI classifies domestic terrorism as “Violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups to further ideological goals stemming from domestic influences, such as those of a political, religious, social, racial, or environmental nature” [

28].

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s definition of domestic terrorism, however, focuses more on “human life,” as it defines domestic terrorism as activities that are a violation of criminal laws and involve acts that are dangerous to human life or potentially destructive of critical infrastructure or key resources intended to intimidate or coerce a civilian population, influence government policy by intimidation, or affect government conduct by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping (Homeland Security Act definition of terrorism, 6 U.S.C. 101(18)). In summary, the definitional criteria for domestic terrorism are the following: (i) the underlying act must violate criminal laws and be dangerous to human life (the “dangerous to human life” phrase is important) and (ii) there must be intent to intimidate/coerce a civilian population, to influence government policy/conduct, or to affect government conduct by mass destruction/assassination/kidnapping. It is worth pointing out, however, that there are no federal domestic terrorism charging statutes in the United States. Though the USA PATRIOT Act (Pub. L. No. 107-56, 115 Stat. 272) defines domestic terrorism, it attaches no sanctions to such conduct (“Responding to Domestic Terrorism: A Crisis of Legitimacy,” 2023). Domestic terrorism charges can only happen on a state level if the state in question has a law on domestic terrorism—some states have them, and some states do not. This means that in most states, domestic terrorism charges cannot be put forward at all, and in the others, it is most likely that Tesla vandalism will not fulfil the criteria of such charges since it lacks the key definitional element, which is intent of intimidating or coercing the population or the government to do something in particular and to advance political or social objectives.

3.2.4. Harassment

We may put forward another legal assessment in the end: harassment. In most jurisdictions, harassment is part of anti-discrimination law. It means an unwanted conduct that violates a person’s dignity or creates an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating, or offensive environment. Harassment is based on a “protected characteristic”—e.g., real or perceived race, ethnicity, other identities, and—which is important in our case—political views. In harassment cases, the true intention of the perpetrator is not considered a relevant factor; only the subjective perception of the victim is taken into consideration. If the victim feels humiliated or threatened, or if a hostile environment is created towards them, harassment can be ascertained. In the case of Tesla vandalism, owners of Tesla vehicles have expressed in multiple cases that they feel threatened and targeted by these actions. In U.S. law, harassment is a generally narrower concept, often used in civil and criminal contexts to describe unwanted conduct directed at a specific person (or persons) causing alarm, annoyance, or distress and serving no legitimate purpose. While statutes vary by state, criminal harassment or “stalking” (the terms are often used interchangeably) generally requires proof of (i) a “course of conduct” (a pattern of two or more acts) (ii) directed at a “specific person” (iii) that would cause a “reasonable person” to suffer substantial emotional distress or to fear for their safety or the safety of others (iv) in which the perpetrator acted with the intent to cause, or with reckless disregard for causing, this fear or distress. A single act of vandalism, therefore, cannot be “harassment.” However, repeatedly vandalizing the same person’s car could be. In the Tesla vandalism cases, the actions, therefore, cannot be assessed as harassment.

3.2.5. Protected Expression of Opinion

If we conclude that these actions are not hate crimes or domestic terrorism incidents, then we should examine the other end of the possible legal assessments. Are these actions an expression of strong political opinion and, therefore, protected under the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution? Expression of opinion, including political opinion, is protected in the United States by the First Amendment to the Constitution, which sets forth that “Congress shall make no law […] abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press…”. This is not only valid for spoken opinions; there is also expressive [

29] conduct or symbolic speech, which includes activities such as picketing and marching, distribution of leaflets, flag desecration, and draft card burnings. This means that conveying a strong political message through the destruction of objects can be a form of protected speech. Even the act of burning the national flag as a symbolic gesture of protest is protected since the 1990 decision in

United States v. Eichman overturned convictions of flag burners and rejected a law designed to protect the physical integrity of the flag (Eichman 496 U.S. 310). The Supreme Court has said that conduct will be sufficiently communicative (…) to bring the First Amendment into play if there is an intent to convey a particularized message and (…) if the likelihood was so great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it (Spence 418 U.S. 405). It is likely that perpetrators of Tesla vandalism would want to convey a clear political message of dissent from the decisions of President Trump and the political activities of Tesla owner Elon Musk.

Why does freedom of expression or political protest come into question at all? There is a likely analogy to some actions during the Black Lives Matter/Floyd protests of 2020. In the wake of the civil unrest that ensued following the killing of George Floyd in May 2020, numerous monuments and memorials associated with racial injustice were either vandalized, destroyed, or formally removed, or officials pledged for their removal. While these actions occurred predominantly within the United States, similar cases occurred in other countries. Several of the monuments targeted had long been the focus of sustained efforts—often extending over several years—to secure their removal, with such efforts frequently involving legislative initiatives and/or judicial proceedings. In certain instances, removals were carried out pursuant to lawful and official processes; however, in other cases—most notably in the states of Alabama and North Carolina—laws prohibiting the removal of monuments were deliberately broken. In these cases, the reactions of the authorities were mixed. Montgomery police have charged four people with first-degree criminal mischief, a felony, in connection with bringing down a statue of Robert E. Lee in front of the Montgomery high school named after the Confederate general [

30]. In Raleigh, North Carolina, police were initially told to stand down as protesters tried to remove statues from the North Carolina Capitol building. Later, a man was arrested in connection with this incident and charged with first-degree trespassing, entering/remaining, and resisting a public officer [

31]. On the other hand, no arrests were made when demonstrators pulled down the statue of Albert Pike and set it ablaze in Washington, D.C. [

32]. In most of the Black Lives Matter protests’ statue defacings or topplings, local officials took action themselves, removing temporarily or permanently the controversial monuments, like in the case of Boston, where the statue of Christopher Columbus was toppled by protestors and then put in storage by the city council [

33].

In the Tesla vandalism cases, the political message may be clear, but the method of conveying it is where the key issue lies. The perpetrators were vandalizing other people’s property and defacing private business entities. As for the location, political protests and other expressions of views are mostly free to be conducted in public spaces, according to the public space doctrine. However, the First Amendment does not require individuals to turn over their homes, businesses, or other property to those wishing to communicate about a particular topic (

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961)). This includes the plaza of shopping malls (

Hudgens v. NLRB, 424 U.S. 507 (1976)) as well. So, defacing car dealerships and business fronts is not protected by free speech. The other issue is the destructive nature of such conduct. Expressive conduct is evaluated under a less stringent constitutional standard than pure speech and thus is more subject to regulation and restriction (Johnson, 491 U.S. 397). In the O’Brien case, the United States Supreme Court held that there were limits to how far it would extend symbolic speech protections. One unprotected area involved violations of otherwise valid laws (O’Brien 391 U.S. 367). In the Brandenburg case, the Supreme Court stated that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not extend to instances where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action (

Brandenburg v. Ohio 395 U.S. 444 (1969)). Setting fire to cars and dealerships or defacing them clearly constitutes a lawless action and is, therefore, not protected under the First Amendment [

34,

35]. The only imaginable exception to this would be if someone were to deface their own Tesla vehicle.

3.2.6. Possible Legal Conclusions

Summarizing the possible legal assessments of the Tesla vandalism cases, we can compare the differential criteria of them. Between property crime and hate crime, the differentiator is motive. Vandalizing a random car is a property crime. A hate crime adds a biased motivation element. The defendant must act because of the victim’s protected characteristic (actual or perceived). So, vandalizing that same car while spray painting a racial slur or Nazi symbol, or because the owner is (or is perceived to be) of a certain religion, transforms the motive into an element of a hate crime. This is seen in a few of the Tesla vandalism cases (as cited above in People v. Robert Haymore and People v. Natasha Cohen). The differentiator between property crime and domestic terrorism is the intent to intimidate/coerce a civilian population or influence government policy. Thus, even if vandalism causes property damage, unless the act is dangerous to human life and intended to intimidate/coerce a civilian population or influence policy/government, it will not reach the domestic terrorism definition. Another key difference is that domestic terrorism typically implicates political or ideological goals and threats to public safety, not mere property damage. Comparing hate crimes and domestic terrorism, the differentiator is the ultimate target of intimidation. A hate crime is intended to terrorize the victim and their identity group. Domestic terrorism is intended to intimidate or coerce the government or the entire civilian population to achieve a political/social goal. The legal classification depends on the specific intent proven. Between the above detailed criminal acts and harassment, the differentiator is repetition and target. The act has to be committed against the same person in a repetitive manner.

Reviewing actual cases of Tesla vandalism, we conclude that the authorities prosecute such cases as property crimes, and in a few distinct cases, as hate crimes. In one of the cases, Justin Fisher was charged with four counts of Defacing Public/Private Property in a D.C. Superior Court after allegedly leaving graffiti/markings on Teslas around Capitol Hill. The case was investigated as a property crime (criminal mischief/defacement) (Charges Filed for Vandalizing Tesla Vehicles in the District, 2025). Domestic terrorism charges were not raised against the suspect even after he allegedly used Molotov cocktails and a 0.30 caliber AR-style firearm to damage and destroy five Tesla vehicles and spray graffiti that said “Resist” on the front of the building. He was charged with arson and unlawful possession of an unregistered firearm [

24]. Some of the cases were investigated as hate crimes (see the above-cited

People v. Robert Haymore and

People v. Natasha Cohen). Domestic terrorism charges have not been used in these Tesla cases; even severe incidents (Molotovs thrown at chargers/cars) have been charged under arson/destructive device statutes.

We may, therefore, conclude that the Tesla vandalism cases neither fall in the category of hate crime and domestic terrorism, nor can they be considered legitimate expressions of political views protected as free speech. Despite the political motivation and the perceived message to be conveyed, the most likely outcome of the trials in these cases is property crime. The arrests and accusations of the perpetrators in the United States also point in this direction since they are charged with various cases of destruction of property, sometimes together with illegal possession of destructive materials or weapons.

3.3. Environmental Effect of Concentrated Hate on Tesla Vehicles

While Tesla remains a single market actor, its high symbolic market share [

36] in consumer perception means that the consequences of vandalism and political polarization extend beyond brand-specific harm. When the most visible e-vehicle manufacturer becomes the focal point of political controversy, this may undermine consumer confidence in e-vehicle technology more broadly [

37]. This potential “contagion effect” suggests that negative sentiment toward Tesla can spill over into general electric mobility trends, influencing sales, innovation investment, and the pace of transition toward sustainable transport [

38].

Therefore, in this section, we are focusing on the e-vehicle market in light of the recent decline of Tesla sales. Our research seeks answers to the question of whether the negative opinions of Tesla have affected the overall market of e-vehicles. Tesla is not only one player in the field of the electric vehicle market, but it is one of the most visible and influential brands, as for many consumers and observers, Tesla can be seen as synonymous with electric vehicles. So, the authors assumed that as the public perception of the electric vehicle category is often shaped by the news about Tesla, a possible negative sentiment towards the company can spill over to the general attitude towards the e-vehicle industry. As Herzinger and others [

39] suggest, e-vehicles hold symbolic value, expressing the owner’s identity, values, and status, and their empirical research resulted in the observation that an electric vehicle’s symbolic value and identity were stronger among individuals nearer to a purchase decision. This research is the basis of our hypothesis that the negative narrative regarding Tesla can have a direct and short-term hit on the e-vehicle industry.

First, we examine data on the global e-vehicle market. Since the automotive industry is one of the most fossil fuel-based and CO2-emitting industries, the vehicles are symbols of CO2 emissions and environmental pollution. As the fact shows, approximately 80% of CO2 is generated from the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas (Maximillian, Glenn, & Matthias, 2019). The global trends show that electric vehicle sales have risen from 3 million units in 2020 to 17 million units in 2024 (IEA, 2025); meanwhile, the global vehicle fleet remains overwhelmingly dependent on fossil fuels. In 2024, more than 95 percent of vehicles in circulation still had internal combustion engines (Pisani-Ferry et al., 2025).

The motivators and behavioral factors of daily access to mobility opportunities are (1) functional sustainability, (2) principle compatibility, and (3) symbolic suitability [

40,

41]. Functional sustainability focuses on objective or less subjective geographical capacities, infrastructural capacities, and availability, but the principal compatibility and symbolic suitability are heavily exposed to the subjective attitudes of the consumers. As the global consumer trends emerge, the sustainability attitude is becoming more and more important. However, the meaning of sustainability in the automotive industry can only be understood in very general terms and, naturally, has different meanings depending on the region, continent, or even country. And even sustainability has three pillars, namely, the societal, the economic, and the environmental pillars as dimensions of sustainability (Schrijver, 2008). In recent years, because of the public debate on environmental and climate issues and as an obvious response to this, most major actors in the automotive industry have made sustainability goals part of their corporate identity, with the intention of gaining a competitive advantage by (over)emphasizing sustainability. One cannot deny the importance of sustainability. When a random search on the websites of the industry actors shows at least one topic about sustainability or corporate responsibility with sustainability aspects. The majority of the eight largest automotive companies have already dedicated a webpage to sustainability or corporate social responsibility or commitments in general as a priority issue, and the leading actors have also accepted the Guiding Principles to Enhance Sustainability Performance in the Supply Chain. As the effects of climate change became more apparent and as they entered into the center of global discussions, the automotive industry came under more pressure than ever to provide alternatives with lower fossil fuel emissions or less carbon or zero-emission goals. Therefore, the industry dipped into the electric vehicle market and produced its own models [

42].

Electric and autonomous vehicles could be more sustainability-oriented, have zero carbon emissions, and be intelligent design-based solutions that are taken into account as a necessary reconsideration of the automotive industry against the hateful behavior towards vehicles in a more and more sustainability-conscious world [

43,

44,

45]. The sustainability perception and decision factor among buyers and consumers is undeniably increasing. It is also accelerated by the growing number of ESG rules worldwide (environmental, social, and governance rules on companies), the consumers’ changing attitudes (eco-friendliness), and the potential climate litigation against industry actors.

The 2022-based KPMG survey emphasized that 31% of the consumers considered zero emissions as extremely important, 39% labeled it important, 23% considered it moderately important, and only 7% said that it was less important [

8]. One of the main findings of the survey was that zero percent responded that the sustainability aspects do not play a role in the decision-making process of buying vehicles.

The Kantar Report [

46] from 2023 underlines that 16% of consumers prioritize sustainability as a key factor in their decision-making process, while Millennials are most likely to put emphasis on sustainability in the automotive market (20% of Millennials say that sustainability issues are behind their decision). The factors of sustainability reflect that 69% of consumers put emphasis on the air quality aspects of using vehicles, and 64% of them emphasized the reduced carbon footprint of the vehicle [

46]. However, the younger the generation is, the more sustainable their decisions are. Generation X put even more focus on air quality (70%) and a reduced carbon footprint (71%), while the environmentally conscious Generation Z and Millennial consumers display near-equal value across all sustainability areas, showcasing a more holistic approach to eco-conscious decision-making. It is also revealed that 40% of global electric vehicle owners were primarily motivated by making a positive impact on the environment by purchasing electric vehicles instead of fossil fuel-based internal combustion engine-based vehicles. As for the global generational trends, 41% of Generation Z and 39% of Millennial consumers are more likely to prefer public transportation for sustainability reasons compared to 25% of Boomers or 32% of Generation X members, which undeniably reflects the global trends of the younger generations’ changing environmental attitude towards more sustainable as well as cost and fuel saving ways. Therefore, based on the polls and attitude analysis of the younger generations’ behavior, the automotive industry shall be ready for a more sustainable way of production, more environmentally friendly alternatives, and electric vehicles, as well as intelligent design of car production.

Tesla Inc. has been widely regarded as a market leader in the electrification of mobility, and it has strong branding around sustainability and innovation. Model S, Model 3, and, in some ways, the Cybertruck, served as symbols of environmental consciousness and technological innovation but also economic elitism [

36]. These vehicles are not only transportation tools but also status symbols, in which the symbolic element is a main character for the targeted vandalism we experienced during the first quarter of 2025. As Tesla dominates media coverage of e-vehicles, Elon Musk’s personal visibility amplifies the effect of a possible negative turn regarding public opinion. Political controversy, public criticism, or legal issues involving Elon Musk or Tesla often get framed in the media discussion as “e-vehicle issues” [

47], so as we are passing towards the end of 2025, the authors of this paper are assuming that there will be an overall negative trend on the sales of Tesla and possibly an overall negative trend in e-vehicle sales in the U.S.

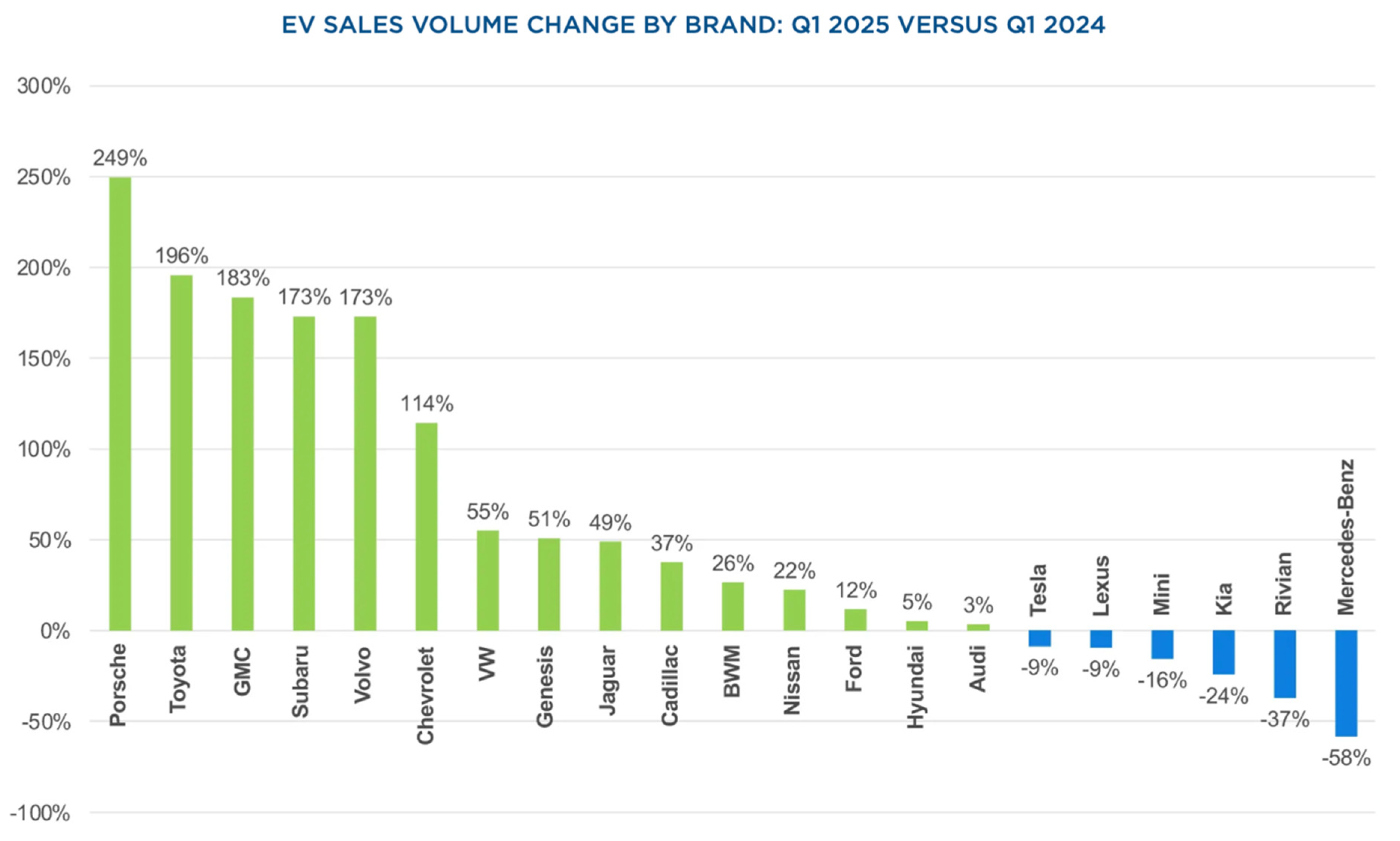

Our data indicate that the political controversy surrounding Elon Musk’s governmental role has produced market effects extending beyond Tesla itself. In Q1 2025, Tesla experienced a 9% decline in sales year over year while the wider U.S. EV market grew by 11.4% during the same period. This divergence suggests a spillover risk, in which negative sentiment and symbolic violence directed toward Tesla may weaken broader consumer confidence in electric mobility. As Tesla remains a leading reference point for the EV sector, reputational and safety concerns targeted at the company can, therefore, delay progress toward sustainability goals and introduce a new socio-political barrier to e-vehicle adoption.