Transport Sector GHG Mitigation Measures: Abatement Costs Application Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

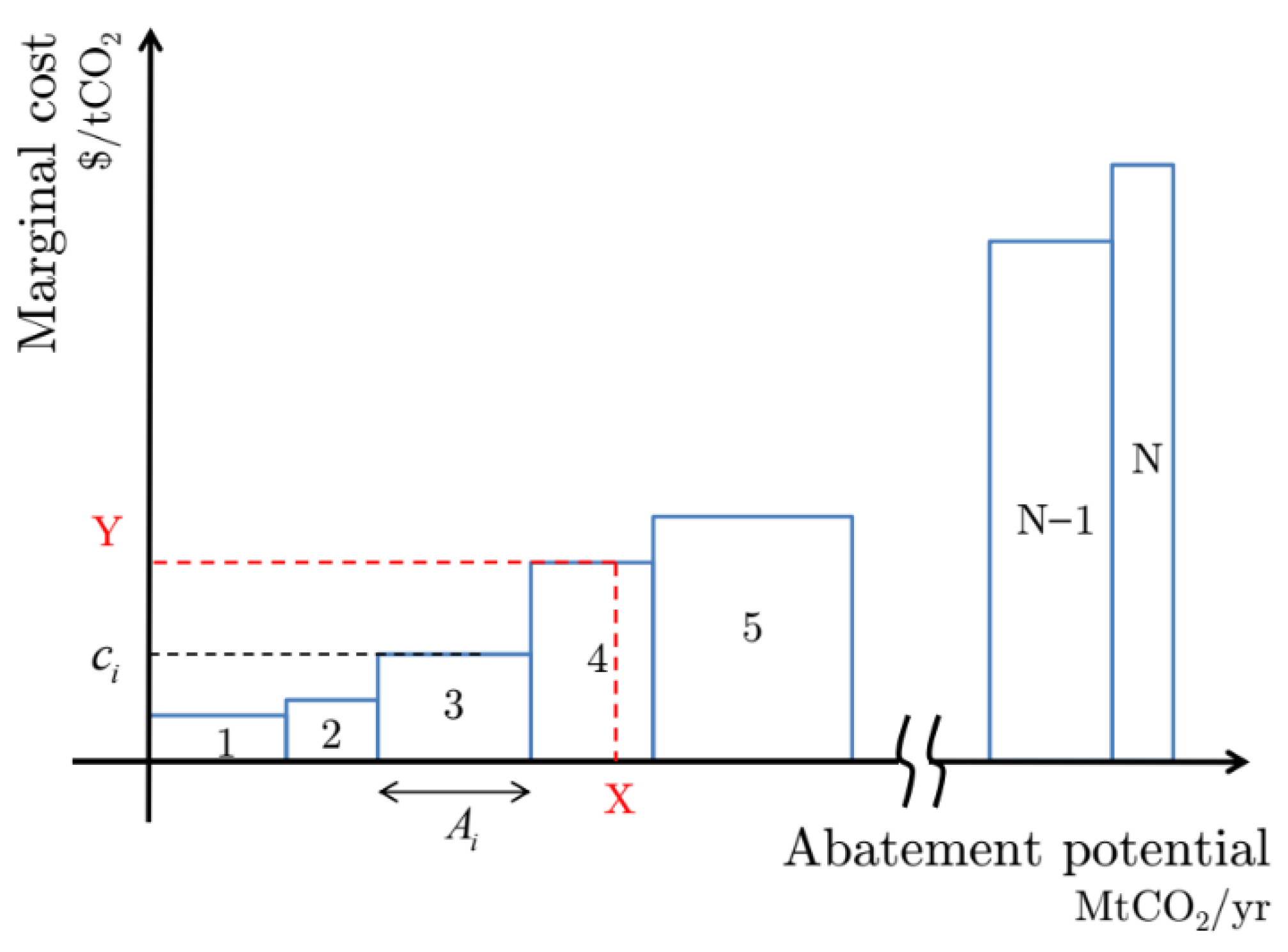

2. Background Information

- Ci: Marginal Abatement Cost for Measure N.

- Capexi: Capital Expenditure for measure N.

- Opexi: Operational Expenditure for measure N.

- r: discount rate.

- t: projected year.

- t0: BAU year.

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Articles Selected and Characterization

4.2. Assumptions and Methodological Approach

4.3. Calculating the Marginal Abatement Cost (MAC)

4.4. Mitigation Measures Applied

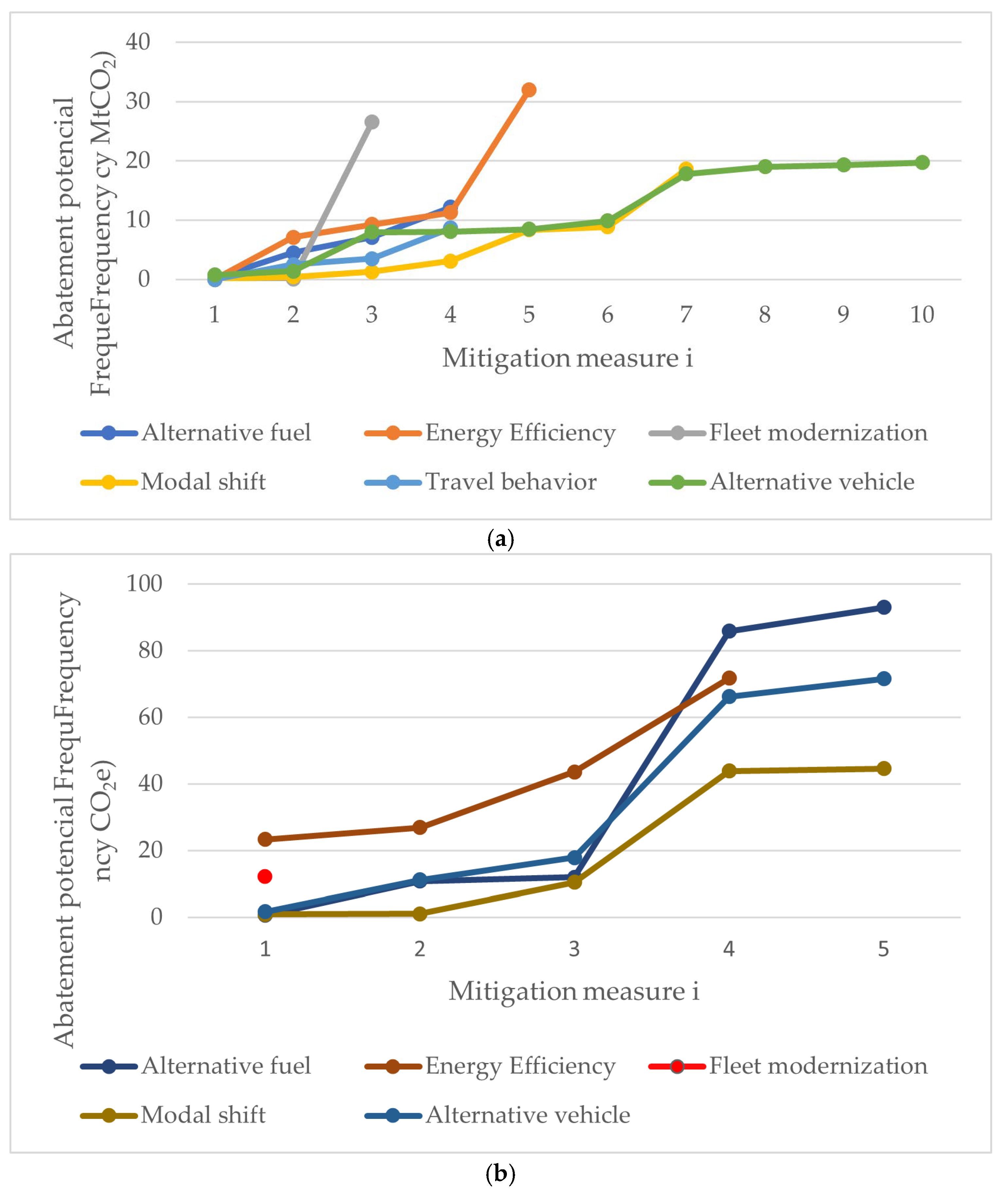

4.5. Impact of the Mitigation Measures

4.6. Policy Implications Based on the Analyzed Studies

5. Discussion

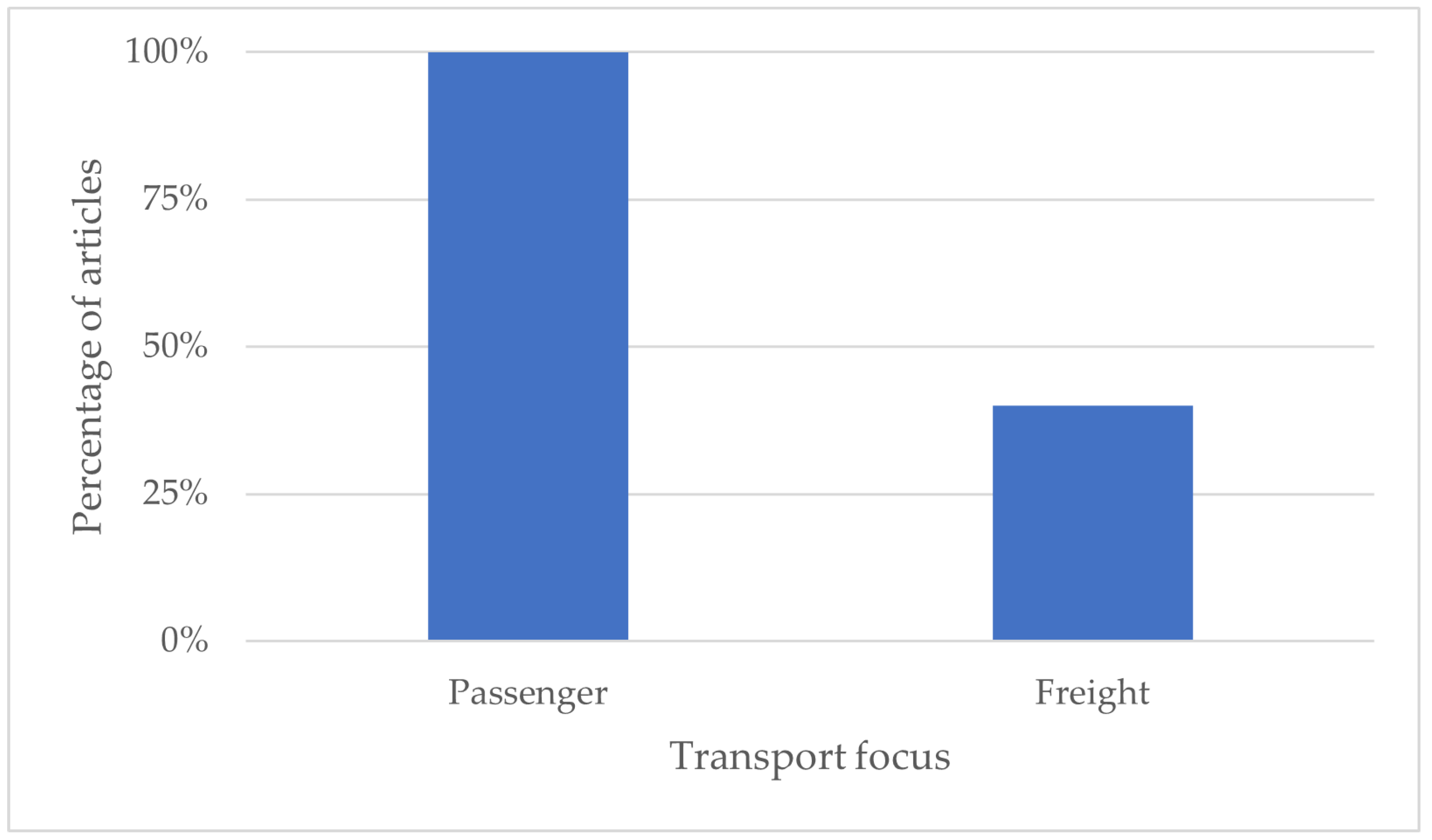

5.1. The Gap in Freight Transport Application

- Data complexity: The freight sector is highly fragmented, involving multiple private actors, complex logistics, and heterogeneous fleets, making the collection of cost and activity data significantly more difficult than in passenger transport, which is usually centered on public institutions [39].

- Transnational nature: Freight (road, sea, air) often operates in international corridors, which complicates national scope analyses that are common in MAC curve studies aligned with NDCs [40].

- Investments periods: Freight infrastructure (railways, ports) has very long investment cycles, making cost–benefit analysis more complex than replacing passenger vehicles [41].

5.2. Implications of Methodological Approach

5.3. Mitigation Measures and Their Cost and Abatement Variation

5.4. Political Relevance

5.5. Future Research

- Develop robust MAC curves for the freight transport sector.

- Employ hybrid methodologies to capture both technical feasibility and macroeconomic impacts.

- Explore the standardization of abatement potentials (such as a percentage reduction) to allow for better comparability between studies.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MAC | Marginal Abatement Cost |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contributions |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| PHEV | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| TDM | Travel Demand Management |

| ASI | Avoid–Shift–Improve |

| ASIF | Activity–Structure–Intensity–Fuel |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

Appendix A

| Paper | Mitigation Measures | Standardized Mitigation Measures |

|---|---|---|

| [17] | Improvement of driver behavior | Energy efficiency |

| Improvement of travel behavior | Travel behavior | |

| Advancement of vehicle equipment | Fleet modernization | |

| Introduction of low-carbon fuels | Alternative fuels | |

| Improvement of vehicle fleet | Fleet modernization | |

| [18] | Improved fuel efficiency and green driving | Energy efficiency |

| Electric mobility | Alternative vehicle | |

| Reduction in freight fleet oversupply and renewal | Fleet modernization | |

| Fuel substitution | Alternative fuel | |

| Modal change | Modal shift | |

| [19] | Urban form, walking, cycling, and public transport | Modal shift |

| Car-sharing and ride-sharing | Travel behavior | |

| Cars with reduced energy consumption | Energy efficiency | |

| Cars exploiting alternative energy | Alternative fuels | |

| Alternative fuels | Alternative fuels | |

| Energy efficiency in road freight vehicles | Energy efficiency | |

| Alternative energy in freight transport | Alternative fuels | |

| [14] | Improved fuel economy fully implemented | Energy efficiency |

| Improved fuel economy partially implemented | Energy efficiency | |

| EV | Alternative vehicle | |

| Natural gas vehicle | Alternative fuel | |

| [20] | HEV | Alternative vehicle |

| BEV | Alternative vehicle | |

| [21] | New vehicles | Fleet modernization |

| HEV | Alternative vehicle | |

| PHEV | Alternative vehicle | |

| BEV | Alternative vehicle | |

| TDM | Travel behavior | |

| Sedan modal shift | Modal shift | |

| Taxi modal shift | Modal shift | |

| Motorcycle modal shift | Modal shift | |

| [22] | BRT | Modal shift |

| Urban toll | Modal shift | |

| Tramway | Modal shift | |

| EV-HEV | Alternative vehicle | |

| Car-sharing | Travel behavior | |

| [23] | Efficient vehicles | Energy efficiency |

| HEV | Alternative vehicle | |

| PHEV | Alternative vehicle | |

| BEV | Alternative vehicle | |

| Travel demand management | Travel behavior | |

| Modal shift bus | Modal shift | |

| Modal shift non-motorized | Modal shift | |

| Modal shift train | Modal shift | |

| [12] | Urban public transport enhancements and expansion of the electric and hybrid buses fleet | Alternative vehicle |

| Expansion of the electric and hybrid urban freight fleet | Alternative vehicle | |

| Changes in freight transport patterns and infrastructure—rail | Modal shift | |

| Changes in freight transport patterns and infrastructure—water | Modal shift | |

| Expansion of active transport and tele-activities | Modal shift | |

| Logistics optimization | Energy efficiency | |

| Increased use of hydrous ethanol | Alternative fuel | |

| Increased use of biodiesel | Alternative fuel | |

| Expansion of the electric and hybrid light-duty passenger fleet | Alternative vehicle | |

| Expansion of mass transportation systems Increased use of biokerosene | Modal shift Alternative fuel | |

| [24] | Improved Fuel Economy | Energy efficiency |

| EV | Alternative vehicle | |

| HEV | Alternative vehicle |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- IRENA. Energy Transition Outlook. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Energy-Transition/Outlook? (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Climate Watch. GHG Emissions. Available online: https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions?breakBy=sector&chartType=line&end_year=2022§ors=energy%2Ctotal-including-lucf%2Ctransportation&start_year=1990 (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- ITF. Decarbonising Transport Initiative. Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/decarbonising-transport (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- MCTI. Brazil’s National Inventory Report of Anthropogenic Emissions by Sources and Removals by Sinks of Greenhouse Gases. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/644855 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- IEA. Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach–Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-roadmap-a-global-pathway-to-keep-the-15-0c-goal-in-reach (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Kesicki, F.; Ekins, P. Marginal Abatement Cost Curves: A Call for Caution. Clim. Policy 2012, 12, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.K.; Kuo, L.; Chou, K.-L. The Applicability of Marginal Abatement Cost Approach: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Chairat, A.S.; Abdullah, L.; Maslan, M.N.; Batih, H. Applications of Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MACC) for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Review of Methodologies. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2022, 21, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.-D.; Dong, K.-Y.; Zhang, K.; Liang, Q.-M. The Hotspots, Reference Routes, and Research Trends of Marginal Abatement Costs: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt-Schilb, A.; Hallegatte, S. Marginal Abatement Cost Curves and the Optimal Timing of Mitigation Measures. Energy Policy 2014, 66, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goes, G.V.; Schmitz Gonçalves, D.N.; de Almeida D’Agosto, M.; de Mello Bandeira, R.A.; Grottera, C. Transport-Energy-Environment Modeling and Investment Requirements from Brazilian Commitments. Renew. Energy 2020, 157, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.A.N.; Szklo, A.; Branco, D.A.C. Implementation of Maritime Transport Mitigation Measures According to Their Marginal Abatement Costs and Their Mitigation Potentials. Energy Policy 2022, 160, 112699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Tan, X.; Gu, B.; Guo, J.; Jiang, J.; Wang, D.; Tang, J. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis on Improving Fuel Economy and Promoting Alternative Fuel Vehicles: A Case Study of Chongqing, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 323, 129075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Huang, Y.; Liao, C.; Zhao, D. Sustainable Development Path Research on Urban Transportation Based on Synergistic and Cost-Effective Analysis: A Case of Guangzhou. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 71, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations UN Regrets US Exit from Global Cooperation on Health, Climate Change Agreement. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/01/1159211 (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Dedinec, A.; Markovska, N.; Taseska, V.; Duic, N.; Kanevce, G. Assessment of Climate Change Mitigation Potential of the Macedonian Transport Sector. Energy 2013, 57, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa Valderrama, M.; Cadena Monroy, Á.I.; Behrentz, E. Challenges in Greenhouse Gas Mitigation in Developing Countries: A Case Study of the Colombian Transport Sector. Energy Policy 2019, 124, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liimatainen, H.; Pöllänen, M.; Viri, R. CO2 Reduction Costs and Benefits in Transport: Socio-Technical Scenarios. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2018, 6, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, A.R.; Park, W.Y.; Witt, M.; Phadke, A. Hybrid- and Battery-Electric Vehicles Offer Low-Cost Climate Benefits in China. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakkumaran, S.; Limmeechokchai, B. Low Carbon Society Scenario Analysis of Transport Sector of an Emerging Economy—The AIM/Enduse Modelling Approach. Energy Policy 2015, 81, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saujot, M.; Lefèvre, B. The next Generation of Urban MACCs. Reassessing the Cost-Effectiveness of Urban Mitigation Options by Integrating a Systemic Approach and Social Costs. Energy Policy 2016, 92, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayatilaka, P.R.; Limmeechokchai, B. Scenario Based Assessment of CO2 Mitigation Pathways: A Case Study in Thai Transport Sector. Energy Procedia 2015, 79, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, M.M.; Espinosa, M.; Virgüez, E.A.; Behrentz, E. Uncertainty of Greenhouse Gas Emission Models: A Case in Colombia’s Transport Sector. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 4606–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- GIZ. Sustainable Urban Transport: Avoid-Shift-Improve (A-S-I). Available online: https://sutp.org/publications/sustainable-urban-transport-avoid-shift-improve-a-s-i/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- IEA. Carbon-Dioxide Emissions from Travel and Freight in Iea Countries: The Recent Past and the Long-Term Future. Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/Onlinepubs/trcircular/492/492-005.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- MOEPP. The Republic of North Macedonia First NDC (Updated Submission). Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/497726 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- MOEPP. Long-Term Strategy on Climate Action and Action Plan. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/309566 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Republica de Colombia. Contribución Determinada a Nivel Nacional (NDC 3.0) de Colombia-Transformaciones Para La Vida. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/2025-09/NDC%203.0%20Declarativa%20Colombia%20Transformaciones%20para%20la%20Vida%20V.25.09.2025%20Gob.%20Nacional.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment of Finland. Carbon Neutral Finland 2035–National Climate and Energy Strategy. Available online: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/164323/TEM_2022_55.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- GIZ. Towards Zero Emissions. Available online: https://changing-transport.org/publications/towards-zero-emissions/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning. Thailand’s 2nd Updated Nationally Determined Contribution. Available online: https://unfccc.int/NDCREG (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- Office of Natural Resources and Environmental Policy and Planning. Thailand’s Long-Term Low Greenhouse Gas Emission Development Strategy (Revised Version). Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/622276 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- French Republic. LOI N° 2019-1428 Du 24 Décembre 2019 d’orientation Des Mobilités. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000039666574 (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- European Parliament. France’s Climate Action Strategy. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2024)767181 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Brazil Government. “Nova NDC Do Brasil Representa Paradigma Para o Desenvolvimento Do País”, Diz Marina Na COP29. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mma/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/nova-ndc-do-brasil-representa-paradigma-para-o-desenvolvimento-do-pais-diz-marina-na-cop29 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- MME. Combustível Do Futuro. Available online: https://www.gov.br/mme/pt-br/assuntos/secretarias/petroleo-gas-natural-e-biocombustiveis/combustivel-do-futuro (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- WEF. Intelligent Transport, Greener Future: AI as a Catalyst to Decarbonize Global Logistics. Available online: https://reports.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Intelligent_Transport_Greener_Future_2025.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- ITF. A Guide to Integrating Transport into Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/transport-ndc-guide (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- IEA. Aligning Investment and Innovation in Heavy Industries to Accelerate the Transition to Net-Zero Emissions–Analysis. Available online: https://www.iea.org/commentaries/aligning-investment-and-innovation-in-heavy-industries-to-accelerate-the-transition-to-net-zero-emissions (accessed on 8 November 2025).

| Database | Query | Filter |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | “abatement cost” and “transport” and “mitigation” (Title) OR “abatement cost” and “transport” and “mitigation” (Author Keywords) OR “abatement cost” and “transport” and “mitigation” (Abstract) | Years: 2010 to 2025 |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (abatement cost AND transport AND mitigation) AND PUBYEAR > 2009 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 | Years: 2010 to 2025 Document type: Article |

| Author (Year) | Title | Country | Transport Mode | Transport Focus | Type of Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dedinec et al. (2013) [17] | Assessment of climate change mitigation potential of the Macedonian transport sector | Macedonia | Road | Passenger | Energy efficiency and alternative fuels |

| Espinosa Valderrama et al. (2019) [18] | Challenges in greenhouse gas mitigation in developing countries: A case study of the Colombian transport sector | Colombia | Road, rail maritime, and air | Passenger and Freight | Alternative vehicles, alternative fuels, modal shift, public transport, and energy efficiency |

| Liimatainen et al. (2018) [19] | CO2 reduction costs and benefits in transport: socio-technical scenarios | Finland | Road | Passenger and Freight | Alternative vehicles, alternative fuels, and energy efficiency |

| Zeng et al. (2021) [14] | Cost-effectiveness analysis on improving fuel economy and promoting alternative fuel vehicles: A case study of Chongqing, China | China | Road | Passenger | Alternative vehicles, alternative fuels, and energy efficiency |

| Gopal et al. (2018) [20] | Hybrid- and battery-electric vehicles offer low-cost climate benefits in China | China | Road | Passenger | Alternative vehicles |

| Selvakkumaran and Limmeechokchai (2015) [21] | Low carbon society scenario analysis of transport sector of an emerging economy-The AIM/End use modelling approach | Thailand | Road and rail | Passenger and Freight | Alternative vehicles, alternative fuels, and modal shift |

| Saujot and Lefèvre (2016) [22] | The next generation of urban MACCs. Reassessing the cost-effectiveness of urban mitigation options by integrating a systemic approach and social costs | France | Road and rail | Passenger | Alternative vehicles and public transport |

| Jayatilaka and Limmeechokchai (2015) [23] | Scenario Based Assessment of CO2 Mitigation Pathways: A Case Study in Thai Transport Sector | Thailand | Road and rail | Passenger | Alternative vehicles and modal shift |

| Goes et al. (2020) [12] | Transport-energy-environment modeling and investment requirements from Brazilian commitments | Brazil | Road, rail, and maritime | Passenger and Freight | Alternative vehicles, alternative fuels, modal shift, and public transport |

| Valenzuela et al. (2017) [24] | Uncertainty of greenhouse gas emission models: A case in Colombia’s transport sector | Colombia | Road | Passenger | Alternative vehicles and fuel efficiency |

| Paper | Methodology | Base Year | Projected Year | Alternative Scenarios | Discount Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | Bottom-up | 2010 | 2020 | 1 | No data |

| [18] | Bottom-up | 2010 | 2030/2050 | 2 | 10% |

| [19] | Not available | 2010 | 2030/2050 | 2 | No data |

| [14] | Bottom-up | 2015 | 2035 | 4 | 5% and 8% |

| [20] | Bottom-up | 2015 | 2030 | 1 | 7% |

| [21] | Bottom-up | 2010 | 2050 | 7 | No data |

| [22] | Bottom-up | 2010 | 2030 | 4 | 4% and 20% |

| [23] | Bottom-up | 2010 | 2050 | 4 | No data |

| [12] | Hybrid | 2020 | 2030 | 3 | 8% |

| [24] | Not available | 2010 | 2040 | 2 | No data |

| Paper | CO2 | CO2e | Base Emissions for the Projected Year (Mt) | Cumulative Potential of Reduced Emissions (Mt) | Average Abatement Cost (USD 2020) e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | X | 2 | 0.45 | 90 USD/tCO2 | |

| [18] | X | 48.6 a | 58.4/449 b | −13/638 c USD/tCO2e | |

| [19] | X | No data | 68 | 81.6 USD/tCO2 | |

| [14] | X | No data | 193 | No data | |

| [20] | X | No data | 2.12 | No data | |

| [21] | X | No data | 1230 | 125.8 USD/tCO2 | |

| [22] | X | No data | 30% d | 373.7 USD/tCO2 | |

| [23] | X | 120 | 840 | No data | |

| [12] | X | 245 | 398 | −123.2 USD/tCO2e | |

| [24] | X | No data | 59 | No data |

| Paper | Mitigation Measures | Potential CO2 or CO2e Reduction per Measure (Mt) | Abatement Cost per Measure (USD 2020) c |

|---|---|---|---|

| [17] | Improvement of driver behavior | 0.02 (CO2) | −625 (USD/tCO2) |

| Improvement of travel behavior | 0.01 | −560 | |

| Advancement of vehicle equipment | 0.03 | −91 | |

| Introduction of low-carbon fuels | 0.26 | 91 | |

| Improvement of vehicle fleet | 0.12 | 98 | |

| [18] | Improved fuel efficiency and green driving | 23.3/152.5 a (CO2e) | No data |

| Electric mobility | 11.2/118.2 | ||

| Reduction in freight fleet oversupply and renewal | 12.2/72.6 | ||

| Fuel substitution | 10.8/69.3 | ||

| Modal change | 0.9/36.7 | ||

| [19] | Urban form, walking, cycling, and public transport | 18.6 (CO2) | −270.1 (USD/tCO2) |

| Car-sharing and ride-sharing | 8.7 | −1497.9 | |

| Cars with reduced energy consumption | 7.1 | 530.7 | |

| Cars exploiting alternative energy | 4.5 | 279.5 | |

| Alternative fuels | 7.1 | 87.9 | |

| Energy efficiency in road freight vehicles | 9.3 | 252.8 | |

| Alternative energy in freight transport | 12.2 | 245 | |

| [14] | Improved fuel economy fully implemented | 71.8 (CO2e) | −66.7 (USD/tCO2e) |

| Improved fuel economy partially implemented | 43.6 | −61.9 | |

| EV | 66.2 | 110.2 | |

| Natural gas vehicle | 12 | −108.4 | |

| [20] | HEV | 1.38 (CO2) | −138 (USD/tCO2) |

| BEV | 0.74 | −515 | |

| [21] | New vehicles | 26.6 (CO2) | 113.7 (USD/tCO2) |

| HEV | 19.3 | 605.1 | |

| PHEV | 17.8 | 47.5 | |

| BEV | 8.5 | 754.9 | |

| TDM | 2.5 | −366.3 | |

| Sedan modal shift | 8.4 | −1173.6 | |

| Taxi modal shift | 0.16 | −328 | |

| Motorcycle modal shift | 0.43 | −938.1 | |

| [22] | BRT | No data | 1203.8/474.3 b (USD/tCO2) |

| Urban toll | 665.5/329.7 | ||

| Tramway | 1220.9/646.7 | ||

| EV-HEV | 1320.1/2046 | ||

| Car-sharing | −1361.7/−2030.6 | ||

| [23] | Efficient vehicles | 11.3 (CO2) | −47 (USD/tCO2) |

| HEV | 9.9 | 76 | |

| PHEV | 8.1 | 508 | |

| BEV | 19.7 | 559 | |

| Travel demand management | 3.5 | −438 | |

| Modal shift bus | 3.1 | −438 | |

| Modal shift non-motorized | 1.3 | −999 | |

| Modal shift train | 8.9 | −2065 | |

| [12] | Urban public transport enhancements and expansion of the electric and hybrid buses fleet | 71.6 (CO2e) | −419.6 (USD/tCO2e) |

| Expansion of the electric and hybrid urban freight fleet | 1.7 | −401.2 | |

| Changes in freight transport patterns and infrastructure—rail | 44.6 | −220.7 | |

| Changes in freight transport patterns and infrastructure—water | 43.9 | −149.2 | |

| Expansion of active transport and tele-activities | 10.5 | −101.4 | |

| Logistics optimization | 26.9 | −42.6 | |

| Increased use of hydrous ethanol | 93 | −15.4 | |

| Increased use of biodiesel | 85.9 | 0.9 | |

| Expansion of the electric and hybrid light-duty passenger fleet | 17.9 | 63 | |

| Expansion of mass transportation systems | 1.1 | 254.1 | |

| Increased use of biokerosene | 0.6 | 456.9 | |

| [24] | Improved fuel economy | 32 (CO2) | 18 (USD/tCO2) |

| EV | 19 | 47 | |

| HEV | 8 | 114 |

| Mitigation Measure | ASI | ASIF |

|---|---|---|

| Modal shift | S | S |

| Alternative vehicles | I | I |

| Energy efficiency | I | I |

| Alternative fuels | S | F |

| Fleet modernization | I | I |

| Travel behavior | A | A |

| Country (Year) | Measures for MAC | Policies/Plans/Strategies Developed |

|---|---|---|

| Macedonia (2013) | Energy efficiency Travel behavior Fleet modernization Alternative fuels | Update of the NDC a in 2021. Target for transport (2030): 10% in final energy consumption [28]. Long-term Strategy on Climate Action and Action Plan; Measures: Biofuels introduction (10% of energy consumption), penetration of HEV and BEV by 2030, introduction of hydrogen and greater penetration of CNG, expansion of HEV for freight transport by 2040, energy efficiency, fleet modernization, modal shift—railway, travel behavior (walking, cycling, and electric scooters) [29]. |

| Colombia (2017; 2019) | Energy efficiency Alternative vehicle Fleet modernization Alternative fuel Modal shift | Update of the NDC in 2025 (version 3). Measures: establishment of the National Adaptation Plan on Climate Action, development of national policies and strategies that promote the use of electric vehicles (600.000 vehicles by 2030), fleet modernization, changes in travel behavior (active mobility: a 5.5%increase in the modal share by 2030), intermodality for freight transport, modal shift (waterway and railway), alternative fuels for public transport [30]. |

| Finland (2018) | Modal shift Travel behavior Energy efficiency Alternative fuels | Follow the Europe Union (EU) NDC, last updated in 2023. Carbon-neutral Finland 2035—national climate and energy strategy. Measures: follow the EU binding CO2 limitations values on cars, vans, and trucks; promote energy efficiency, electric vehicles, biofuels, fleet modernization, and modal shift [31]. |

| China (2018; 2021) | Energy efficiency Alternative vehicle Alternative fuel | NDC published in 2021, progress update in 2022. Measures: promotion of multimodality, energy efficiency, alternative vehicles, alternative fuels, and travel behavior (active mobility and public transportation) [32]. |

| Thailand (2015) | Energy efficiency Alternative vehicle Travel behavior Modal shift Fleet modernization | Updated NDC in 2022. Measures: modal shift, energy efficiency, travel behavior, and alternative vehicles [33,34]. Thailand’s Long-Term Low Greenhouse Gas Emission Development Strategy (Thailand’s LT-LEDS). Measures: alternative vehicles (estimated 30% by 2030), energy efficiency, travel behavior, and alternative fuels [3]. |

| France (2016) | Modal shift Alternative vehicle Travel behavior | Follow the Europe Union (EU) NDC, last updated in 2023. The Law on Mobility Orientation published in 2019. Measures: modal shift, travel behavior, alternative fuels, and energy efficiency [35]. France’s climate action strategy. Measures: alternative vehicles (66% of new cars sales by 2030), travel behavior (increase public transport by 25% by 2030), modal shift (rail transport), and alternative fuels [36]. |

| Brazil (2020) | Travel behavior Alternative vehicle Modal shift Energy efficiency Alternative fuel | Updated NDC in 2024. Measures: alternative fuels (expansion of biofuels share by 50%, Law Fuel of the Future), alternative vehicles, energy efficiency, travel behavior, and modal shift [37]. Law Fuel of the Future [38]: subsidizes the Brazilian strategy for sustainable low-carbon mobility, integrating consolidated public policies such as RenovaBio, the Mover Program, the Brazilian Vehicle Labeling Program (PBEV), and the Vehicle Emissions Control Program (Proconve). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ricci, L.M.; Gonçalves, D.N.S.; D’Agosto, M.d.A. Transport Sector GHG Mitigation Measures: Abatement Costs Application Review. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040195

Ricci LM, Gonçalves DNS, D’Agosto MdA. Transport Sector GHG Mitigation Measures: Abatement Costs Application Review. Future Transportation. 2025; 5(4):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040195

Chicago/Turabian StyleRicci, Lorena Mirela, Daniel Neves Schmitz Gonçalves, and Marcio de Almeida D’Agosto. 2025. "Transport Sector GHG Mitigation Measures: Abatement Costs Application Review" Future Transportation 5, no. 4: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040195

APA StyleRicci, L. M., Gonçalves, D. N. S., & D’Agosto, M. d. A. (2025). Transport Sector GHG Mitigation Measures: Abatement Costs Application Review. Future Transportation, 5(4), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/futuretransp5040195