Factors Related to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention among Older Patients with Heart Disease in Rural Hospitals: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

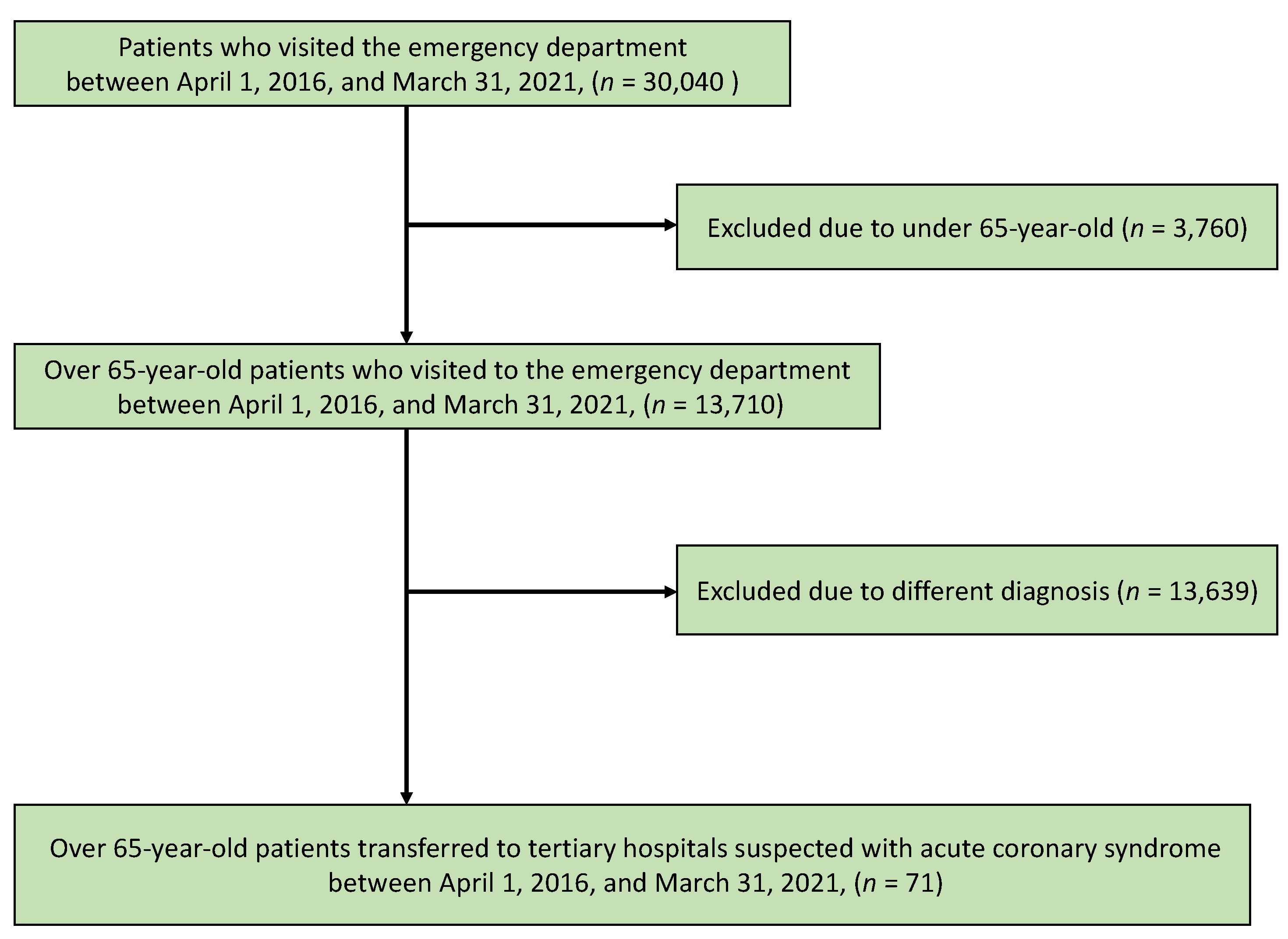

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Primary Outcome

2.3.2. Independent Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Relationship between the Intervention and Demographic Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Manda, Y.R.; Baradhi, K.M. Cardiac Catheterization Risks and Complications; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.H.; Tan, M.; Yan, A.T.; Yan, R.T.; Fitchett, D.; Grima, E.A.; Langer, A.; Goodman, S.G.; Canadian Acute Coronary Syndromes (ACS) Registry II Investigators. Use of cardiac catheterization for non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes according to initial risk: Reasons why physicians choose not to refer their patients. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Blas, S.; Cordero, A.; Diez-Villanueva, P.; Martinez-Avial, M.; Ayesta, A.; Ariza-Solé, A.; Mateus-Porta, G.; Martínez-Sellés, M.; Escribano, D.; Gabaldon-Perez, A.; et al. Acute coronary syndrome in the older patient. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Busby-Whitehead, J.; Alexander, K.P. Acute coronary syndrome in the older adults. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunderson, C.E.D.; Brogan, R.A.; Simms, A.D.; Sutton, G.; Batin, P.D.; Gale, C.P. Acute coronary syndrome management in older adults: Guidelines, temporal changes and challenges [Guidelines]. Age Ageing. 2014, 43, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Ryu, Y.; Sano, C. Older People’s help-seeking behaviors in rural contexts: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, M.; Coetzee, A.R.; Lochner, A. The pathophysiology of myocardial ischemia and perioperative myocardial infarction. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2020, 34, 2501–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bularga, A.; Lee, K.K.; Stewart, S.; Ferry, A.V.; Chapman, A.R.; Marshall, L.; Strachan, F.E.; Cruickshank, A.; Maguire, D.; Berry, C.; et al. High-sensitivity troponin and the application of risk stratification thresholds in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. Circulation 2019, 140, 1557–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, J.I.; Fujiu, K.; Yoneda, K.; Iwamura, T.; Washio, T.; Komuro, I.; Hisada, T.; Sugiura, S. Ionic mechanisms of ST segment elevation in electrocardiogram during acute myocardial infarction. J. Physiol. Sci. 2020, 70, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Filippi, C.R.; Mills, N.L. Rapid cardiac troponin release after transient ischemia: Implications for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2021, 143, 1105–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwani, A.S.; Boldt, L.H.; Huemer, M.; Wutzler, A.; Blaschke, D.; Rolf, S.; Möckel, M.; Haverkamp, W. Atrial fibrillation-induced cardiac troponin I release. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 2734–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, Z.; Katus, H.A.; Rose, N.R. Cardiac troponins and autoimmunity: Their role in the pathogenesis of myocarditis and of heart failure. Clin. Immunol. 2010, 134, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corneliusson, L.; Lövheim, H.; Sköldunger, A.; Sjögren, K.; Edvardsson, D. Relocation patterns and predictors of relocation and mortality in Swedish sheltered housing and aging in place. J. Aging Environ. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.E.; Lawrence, C. Home is where the heart is: The effect of place of residence on place attachment and community participation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Sano, C. Risk of hospital readmission among older patients discharged from the rehabilitation unit in a Rural Community Hospital: A retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, R.; Ueno, A.; Sano, C. Changes in the comprehensiveness of rural medical care for older Japanese patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizutani, S. The future of long-term care in Japan. Asia Pac. Rev. 2014, 21, 88–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.; Szatrowski, T.P.; Peterson, J.; Gold, J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1994, 47, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulia, M.; Salman, T.; O’Connell, T.F.; Balasubramanian, N.; Gaines, R.; Shah, F.; Henry, M.; Leya, F.; Mathew, V.; Bufalino, D.; et al. Impact of emergency medical services activation of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory and a 24-hour/day in-hospital interventional cardiology team on treatment times (door to balloon and medical contact to balloon) for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 124, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, N.L.; Churchhouse, A.M.; Lee, K.K.; Anand, A.; Gamble, D.; Shah, A.S.; Paterson, E.; MacLeod, M.; Graham, C.; Walker, S.; et al. Implementation of a sensitive troponin I assay and risk of recurrent myocardial infarction and death in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome. JAMA 2011, 305, 1210–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013, 48, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Kawai, S.; Taguchi, T. Factors affecting ambulatory status and survival of patients 90 years and older with hip fractures. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2005, 436, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, T.; Arnold-Reed, D.E.; Popescu, A.; Soliman, B.; Bulsara, M.K.; Fine, H.; Bovell, G.; Moorhead, R.G. Multimorbidity in patients Attending 2 Australian primary care practices. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantas, I.; Santana, R.; Sarmento, J.; Aguiar, P. The impact of multiple chronic diseases on hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Wal, H.H.; van Deursen, V.M.; van der Meer, P.; Voors, A.A. Comorbidities in heart failure. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2017, 243, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosking, F.J.; Carey, I.M.; DeWilde, S.; Harris, T.; Beighton, C.; Cook, D.G. Preventable emergency hospital admissions among adults with intellectual disability in England. Ann. Fam. Med. 2017, 15, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J.M.; Markowitz, J.C.; Alegría, A.; Pérez-Fuentes, G.; Liu, S.M.; Lin, K.H.; Blanco, C. Epidemiology of chronic and nonchronic major depressive disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, K.; Furuya, S.; Mori, R. Investigating Factors Associated with Nutritional Status and Risk of Malnutrition in Residents of Disaster Public Housing/ cross-sectional study. J. Jpn. Assoc. Home Care Med. 2021, 2, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, S.; Bueno, H.; Ahrens, I.; Hassager, C.; Bonnefoy, E.; Lettino, M. Optimised care of elderly patients with acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2018, 7, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobre, M.; Brateanu, A.; Rashidi, A.; Rahman, M. Electrocardiogram abnormalities and cardiovascular mortality in elderly patients with CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, E.M.; Ribeiro, A.H.; Paixão, G.M.M.; Ribeiro, M.H.; Pinto-Filho, M.M.; Gomes, P.R.; Oliveira, D.M.; Sabino, E.C.; Duncan, B.B.; Giatti, L.; et al. Deep neural network-estimated electrocardiographic age as a mortality predictor. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashou, A.H.; May, A.M.; Noseworthy, P.A. Artificial intelligence-enabled ECG: A modern lens on an old technology. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2020, 22, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horinishi, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Sano, C.; Ohta, R. Surgical interventions in cases of esophageal hiatal hernias among older Japanese adults: A systematic review. Medicina 2022, 58, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netuveli, G.; Blane, D. Quality of life in older ages. Br. Med. Bull. 2008, 85, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyman, M.F.; Shiovitz-Ezra, S.; Bengel, J. Ageism in the health care system: Providers, patients, and systems. In Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism; Ayalon, T.-R.C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Amano, S.; Ohta, R.; Sano, C. Recognition of anemia in elderly people in a rural community hospital. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, R.; Ryu, Y.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Sano, C.; Könings, K.D. Educational intervention to improve citizen’s healthcare participation perception in rural Japanese communities: A pilot study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, W.C.; Wolff, J.; Greer, R.; Dy, S. Multimorbidity and decision-making preferences among older adults. Ann. Fam. Med. 2017, 15, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Wong, E.; Ciummo, F. Polypharmacy in older adults: Practical applications alongside a patient case. J. Nurse Pract. 2020, 16, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, R.; Sato, M.; Ryu, Y.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Maeno, T.; Sano, C. What resources do elderly people choose for managing their symptoms? Clarification of rural older People’s choices of help-seeking behaviors in Japan. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, A.; Wiligorska, N.; Wiligorska, D.; Frontczak-Baniewicz, M.; Przybylski, M.; Krzyzewski, R.; Ziemba, A.; Gil, R.J. Viral heart disease and acute coronary syndromes — Often or rare coexistence? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, L.; D’Angelo, E.C.; Paolisso, P.; Toniolo, S.; Fabrizio, M.; Angeli, F.; Donati, F.; Magnani, I.; Rinaldi, A.; Bartoli, L.; et al. The value of ECG changes in risk stratification of COVID-19 patients. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2021, 26, e12815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyand, C.M.; Goronzy, J.J. Aging of the immune system. Mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13 (Suppl. S5), 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Intervention | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | + (Exposure) | − (Control) | p-Value |

| n | 31 | 40 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 77.61 (13.76) | 74.90 (16.18) | 0.458 |

| Age ≥80 years (%) | 17 (54.8) | 21 (52.5) | 1 |

| Male patients (%) | 17 (54.8) | 27 (67.5) | 0.329 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 22.77 (4.56) | 24.21 (4.88) | 0.319 |

| Creatinine level (SD) | 1.28 (0.80) | 1.12 (0.58) | 0.341 |

| eGFR (SD) | 64.48 (20.87) | 64.16 (19.79) | 0.935 |

| Troponin level, median (IQR) | 0.24 (0, 1519) | 0.21 (0, 4242) | 0.981 |

| Troponin level ≥0.05 (%) | 20 (66.7) | 27 (67.5) | 1 |

| Creatinine kinase level, median (IQR) | 191 (24, 2936) | 179 (55, 2247) | 0.5 |

| CK-MB, median (IQR) | 16 (2, 146) | 16 (0, 197) | 0.881 |

| Presence of chest pain | 9 (30.0) | 8 (20.0) | 0.404 |

| Hours from onset to transfer, median (IQR) | 6 (1, 168) | 6 (1, 240) | 0.617 |

| Time from onset to transfer <24 h (%) | 10 (32.3) | 10 (25.0) | 0.598 |

| ECG changes | 19 (63.3) | 32 (80.0) | 0.175 |

| CCI ≥5 (%) | 22 (73.3) | 22 (55.0) | 0.139 |

| CCI (%) | |||

| 1 | 1 (3.3) | 4 (10.0) | 0.813 |

| 2 | 2 (6.7) | 3 (7.5) | |

| 3 | 2 (6.7) | 5 (12.5) | |

| 4 | 3 (10.0) | 6 (15.0) | |

| 5 | 8 (26.7) | 8 (20.0) | |

| 6 | 5 (16.7) | 8 (20.0) | |

| 7 | 3 (10.0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| 8 | 3 (10.0) | 4 (10.0) | |

| 9 | 1 (3.3) | 1 (2.5) | |

| 15 | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 17 | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Heart failure (%) | 10 (33.3) | 8 (20.0) | 0.272 |

| Myocardial infarction (%) | 16 (53.3) | 30 (75.0) | 0.077 |

| Asthma (%) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.429 |

| Peptic ulcer (%) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (2.5) | 0.387 |

| Kidney disease (%) | 8 (26.7) | 8 (20.0) | 0.573 |

| Liver disease (%) | 3 (10.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0.307 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 9 (30.0) | 11 (27.5) | 1 |

| Brain infarction (%) | 6 (20.0) | 2 (5.0) | 0.066 |

| Brain hemorrhage (%) | 1 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.429 |

| Hemiplegia (%) | 2 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.18 |

| Connective tissue disease (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.0) | 0.503 |

| Dementia (%) | 3 (10.0) | 3 (7.5) | 1 |

| Cancer (%) | 4 (13.3) | 3 (7.5) | 0.452 |

| Dependent condition (%) | 9 (30.0) | 8 (20.0) | 0.404 |

| Factor | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥80 years (reference: age <80 years) | 1.77 | 0.49–6.41 | 0.39 |

| CCI ≥5 (reference: CCI <5) | 0.23 | 0.06–0.94 | 0.041 |

| Time from onset to transfer <24 h (reference: time ≥24 h) | 0.56 | 0.18–1.70 | 0.3 |

| ECG changes (reference: no ECG change) | 3.24 | 1.00–10.50 | 0.049 |

| Troponin level ≥0.05 ng/mL (reference: troponin level <0.05 ng/mL) | 1.42 | 0.48–4.25 | 0.53 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yamane, F.; Ohta, R.; Sano, C. Factors Related to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention among Older Patients with Heart Disease in Rural Hospitals: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BioMedInformatics 2022, 2, 593-602. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedinformatics2040038

Yamane F, Ohta R, Sano C. Factors Related to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention among Older Patients with Heart Disease in Rural Hospitals: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BioMedInformatics. 2022; 2(4):593-602. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedinformatics2040038

Chicago/Turabian StyleYamane, Fumiko, Ryuichi Ohta, and Chiaki Sano. 2022. "Factors Related to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention among Older Patients with Heart Disease in Rural Hospitals: A Retrospective Cohort Study" BioMedInformatics 2, no. 4: 593-602. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedinformatics2040038

APA StyleYamane, F., Ohta, R., & Sano, C. (2022). Factors Related to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention among Older Patients with Heart Disease in Rural Hospitals: A Retrospective Cohort Study. BioMedInformatics, 2(4), 593-602. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedinformatics2040038