A New Methodology for Detecting Deep Diurnal Convection Initiations in Summer: Application to the Eastern Pyrenees

Highlights

- We have established a methodology using the CAPPI radar product to identify convection initiation in mountainous areas.

- We have validated the objective methodology through comparison with subjective observations.

- The methodology can be applied to any area with available radar data to improve understanding of this type of convection.

- By better identifying convection initiation hotspots, we can apply prevention techniques for managing flash floods in remote areas.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. The Area of Study

2.2. Data Used

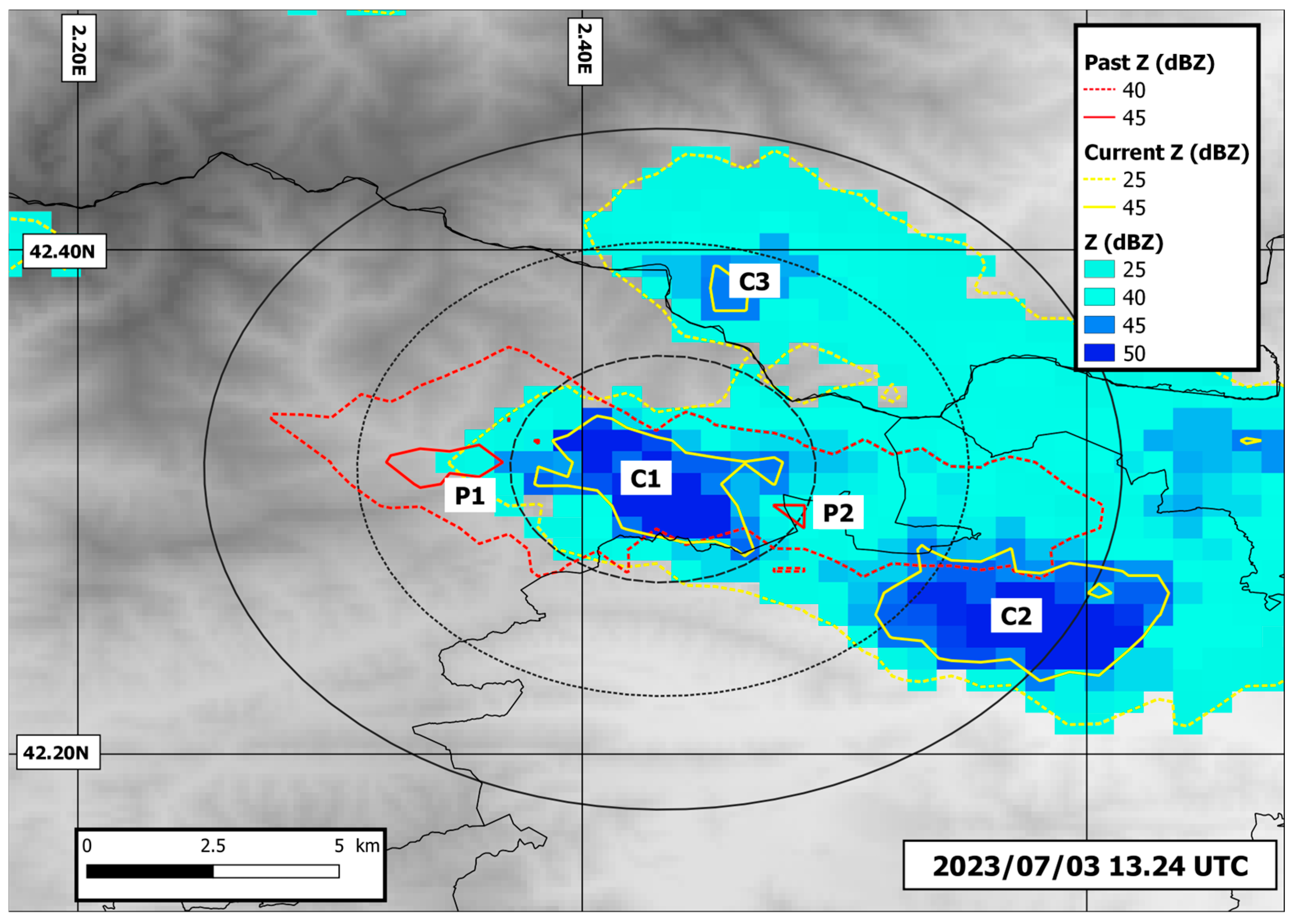

2.3. Methodology

- Is there any reflectivity pixel exceeding 45 dBZ?As explained previously, the selection of this threshold is based on the available literature on convective events in the region [30].

- −

- If not, the procedure waits for the next image (6 min later).

- −

- If yes, it moves to the next question.

- Has the 45 dBZ area reached a size larger than a given threshold?

- −

- If not, the procedure waits for the next image.

- −

- If yes, the script proceeds to the next step.

- Are there any pixels exceeding 45 dBZ in any of the previous Ni images (where Ni is the number of previous images)?

- −

- If not, the 45 dBZ area in the current image is classified as convection initiation.

- −

- If yes, more questions must be addressed.

- Is the distance between the two convective cells (current and previous) lower than a given threshold?

- −

- If not, the current 45 dBZ area is considered a new convective cell.

- −

- If yes, continue with the next question.

- Is there any reflectivity pixel between the two convective cells (current and previous) exceeding a certain threshold?

- −

- If not, the current cell is considered independent from the previous one. Consequently, it is classified as a new convection initiation.

- −

- If yes, the process stops and waits for the next image.

- Convective cell: an area exceeding the 45 dBZ threshold.

- Convection initiation: the first time a convective cell is identified; this is determined according to criteria such as size, the occurrence of previous convection, and the distance to prior occurrences. It should be noted that this time refers to when the radar data reach 45 dBZ, not to the actual onset of convection.

- Valid event: any day with reflectivity cores exceeding 45 dBZ that originate exclusively within the study area, i.e., not moving into the region from any neighboring area.

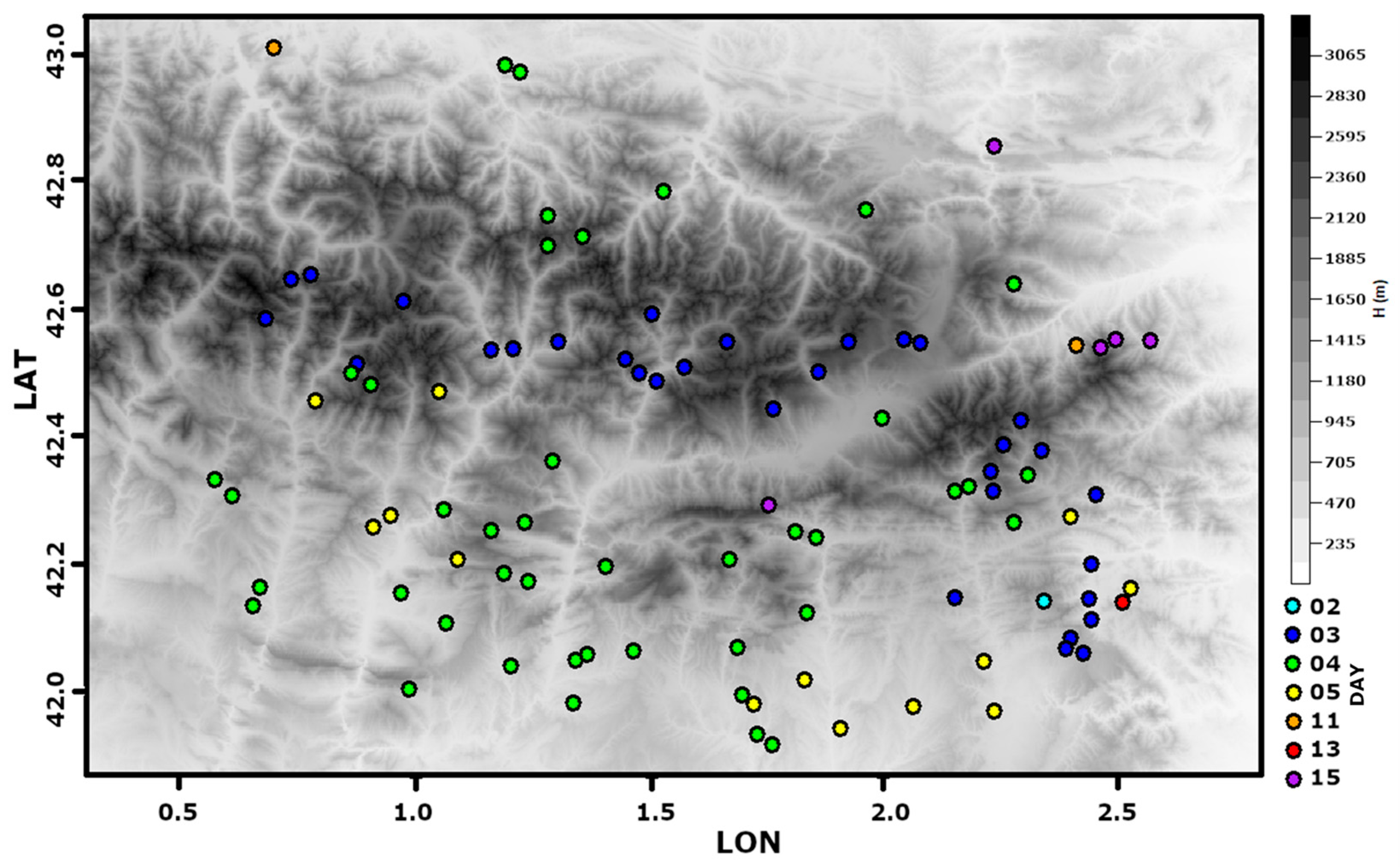

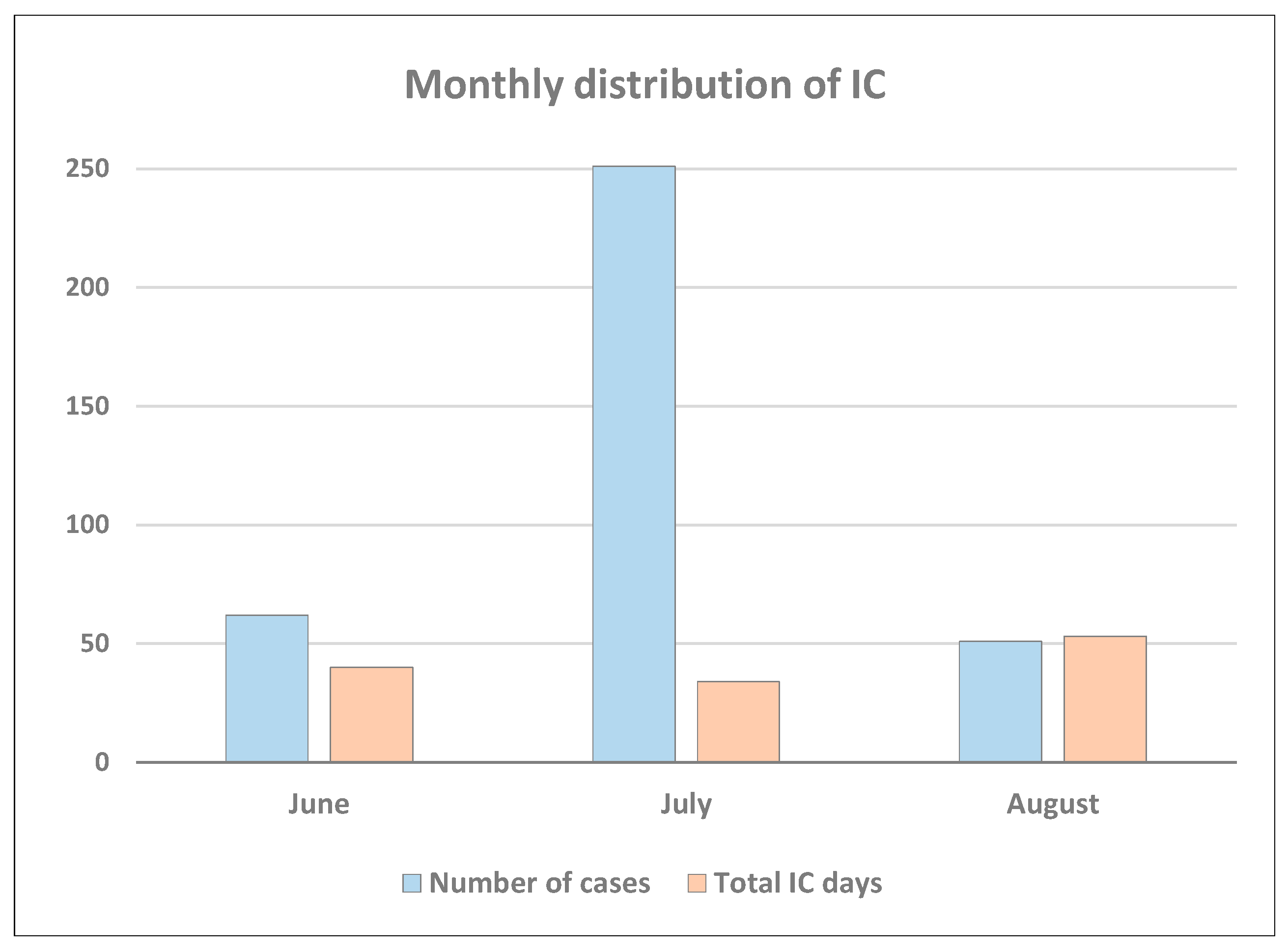

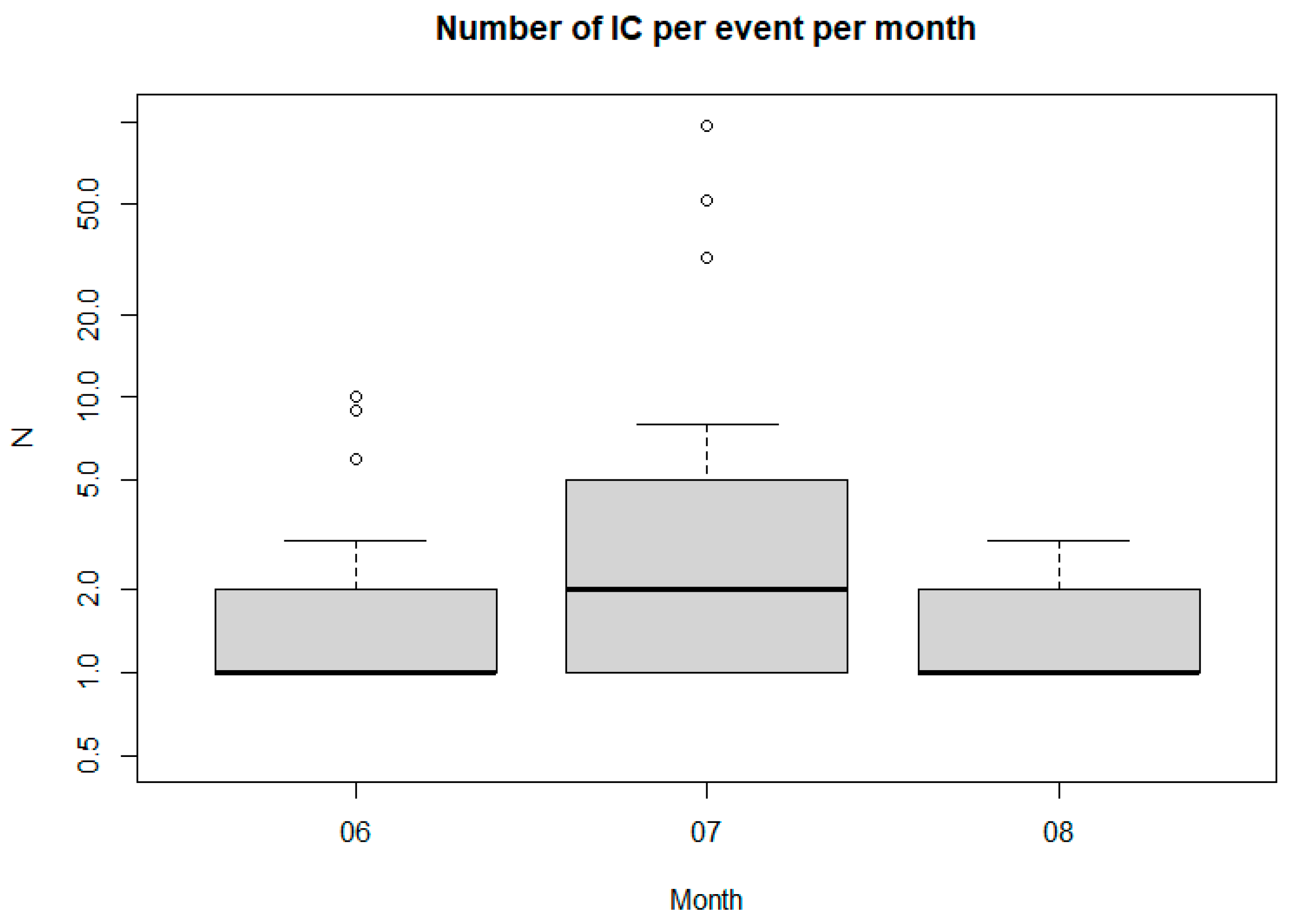

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LFC | Free Convection Level |

| MCS | Mesoscale Convective Systems |

| XRAD | Radar network of the Meteorological Service of Catalonia |

| PPI | Plan Position Indicator |

| CAPPI | Constant Altitude Plan Position Indicator |

| UTC | Universal Time Coordinated |

References

- Doswell, C.A., III; Brooks, H.E.; Maddox, R.A. Flash flood forecasting: An ingredients-based methodology. Weather Forecast. 1996, 11, 560–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, R.H.; Doswell, C.A., III. Severe local storms forecasting. Weather Forecast. 1992, 7, 588–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulikemu, A.; Ming, J.; Xu, X.; Zhuge, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, B.; Aireti, M. Mechanisms of Convection Initiation in the Southwestern Xinjiang, Northwest China: A Case Study. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckwerth, T.M.; Parsons, D.B. A review of convection initiation and motivation for IHOP_2002. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2006, 134, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, C.L.; Rasmussen, E.N. The initiation of moist convection at the dryline: Forecasting issues from a case study perspective. Weather Forecast. 1998, 13, 1106–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulimiti, A.; Sun, Q.; Yuan, L.; Liu, Y.; Yao, J.; Yang, L.; Ming, J.; Abulikemu, A. A Case Study on the Convection Initiation Mechanisms over the Northern Edge of Tarim Basin, Xinjiang, Northwest China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, L.J.; Blyth, A.M.; Burton, R.R.; Gadian, A.M.; Weckwerth, T.M.; Behrendt, A.; Di Girolamo, P.; Dorninger, M.; Lock, S.; Smith, V.H.; et al. Initiation of convection over the Black Forest mountains during COPS IOP15a. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, M.; Serafin, S.; Rotach, M.W. Adverse impact of terrain steepness on thermally driven initiation of orographic convection. Weather. Clim. Dyn. 2023, 4, 725–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, M.; Van Baelen, J.; Richard, E. Influence of the wind profile on the initiation of convection in mountainous terrain. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 137, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshbaum, D.J.; Adler, B.; Kalthoff, N.; Barthlott, C.; Serafin, S. Moist orographic convection: Physical mechanisms and links to surface-exchange processes. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xue, M.; Tan, Z. Convective initiation by topographically induced convergence forcing over the Dabie Mountains on 24 June 2010. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2016, 33, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varble, A.C.; Nesbitt, S.W.; Salio, P.; Hardin, J.C.; Bharadwaj, N.; Borque, P.; DeMott, P.J.; Feng, Z.; Hill, T.C.J.; Marquis, J.N.; et al. Utilizing a storm-generating hotspot to study convective cloud transitions: The CACTI experiment. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2021, 102, 1597–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckwerth, T.M.; Wilson, J.W.; Hagen, M.; Emerson, T.J.; Pinto, J.O.; Rife, D.L.; Grebe, L. Radar climatology of the COPS region. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 2011, 137, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelten, S.; Gallus, W.A., Jr. Pristine nocturnal convective initiation: A climatology and preliminary examination of predictability. Weather Forecast. 2017, 32, 1613–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Chen, G.; Huang, L. Image processing of radar mosaics for the climatology of convection initiation in South China. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. Climatol. 2020, 59, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisi, L.; Martius, O.; Hering, A.; Kunz, M.; Germann, U. Spatial and temporal distribution of hailstorms in the Alpine region: A long-term, high resolution, radar-based analysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2016, 142, 1590–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzato, A.; Serafin, S.; Miglietta, M.M.; Kirshbaum, D.; Schulz, W. A pan-Alpine climatology of lightning and convective initiation. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2022, 150, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapero, L.; Bech, J.; Lorente, J. Numerical modelling of heavy precipitation events over Eastern Pyrenees: Analysis of orographic effects. Atmos. Res. 2013, 123, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llasat, M.C.; Llasat-Botija, M.; Pardo, E.; Marcos-Matamoros, R.; Lemus-Canovas, M. Floods in the Pyrenees: A global view through a regional database. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 24, 3423–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemus-Canovas, M.; Lopez-Bustins, J.A.; Martín-Vide, J.; Halifa-Marin, A.; Insua-Costa, D.; Martinez-Artigas, J.; Trapero, L.; Serrano-Notivoli, R.; Cuadrat, J.M. Characterisation of extreme precipitation events in the Pyrenees: From the local to the synoptic scale. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.; Sánchez, J.L.; Fraile, R. Statistical comparison of the properties of thunderstorms in different areas around the Ebro-Valley (Spain). Atmos. Res. 1992, 28, 237–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresson, E.; Ducrocq, V.; Nuissier, O.; Ricard, D.; de Saint-Aubin, C. Idealized numerical simulations of quasi-stationary convective systems over the Northwestern Mediterranean complex terrain. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 138, 1751–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, V.; Bischoff-Gauß, I.; Kalthoff, N.; Gantner, L.; Roca, R.; Panitz, H.J. Initiation of deep convection in the Sahel in a convection-permitting climate simulation for northern Africa. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 143, 806–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, K.L.; Houze, R.A., Jr. Convective initiation near the Andes in subtropical South America. Mon. Weather. Rev. 2016, 144, 2351–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callado, A.; Pascual, R. Diagnosis and modelling of a summer convective storm over Mediterranean Pyrenees. Adv. Geosci. 2005, 2, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, N.; Rigo, T.; Bech, J.; Soler, X. Lightning and precipitation relationship in summer thunderstorms: Case studies in the North Western Mediterranean region. Atmos. Res. 2007, 85, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Bonet, F.; Rigo, T. A Characterization of the Initiation of the Summer Diurnal Evolution Convection in the Catalan Pyrenees: An 11-year (2010–2020) Radar-Data Based Analysis. Tethys 2022, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech, J.; Gjertsen, U.; Haase, G. Modelling weather radar beam propagation and topographical blockage at northern high latitudes. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. J. Atmos. Sci. Appl. Meteorol. Phys. Ocean. Oceanogr. 2007, 133, 1191–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann, U.; Boscacci, M.; Clementi, L.; Gabella, M.; Hering, A.; Sartori, M.; Sideris, I.V.; Calpini, B. Weather Radar in Complex Orography. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigo, T.; Llasat, M.C. Analysis of mesoscale convective systems in Catalonia using meteorological radar for the period 1996–2000. Atmos. Res. 2007, 83, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatibi, S.M.H.; Ali, J. Harnessing the power of machine learning for crop improvement and sustainable production. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1417912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, D.S. Economic Value and Skill. In Forecast Verification; Jolliffe, I.T., Stephenson, D.B., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric Gilleland. Verification: Weather Forecast Verification Utilities. R Package Version 1.44. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=verification (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

| DIST (km) | VMAX | HIT | FALSE | BASE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.000 | 0.539 | 0.952 | 0.412 | 0.654 |

| 10.000 | 0.528 | 0.970 | 0.442 | 0.698 |

| 15.000 | 0.904 | 0.984 | 0.072 | 0.788 |

| 20.000 | 0.892 | 0.995 | 0.097 | 0.885 |

| 25.000 | 0.968 | 0.995 | 0.021 | 0.886 |

| 30.000 | 0.992 | 0.999 | 0.005 | 0.921 |

| 35.000 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.003 | 0.892 |

| 40.000 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.003 | 0.892 |

| 45.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.898 |

| 50.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.898 |

| TIME (min) | VMAX | HIT | FALSE | BASE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.000 | 0.863 | 0.975 | 0.112 | 0.735 |

| 24.000 | 0.790 | 0.989 | 0.189 | 0.847 |

| 30.000 | 0.800 | 0.991 | 0.181 | 0.854 |

| 36.000 | 0.780 | 0.988 | 0.199 | 0.840 |

| 42.000 | 0.771 | 0.991 | 0.212 | 0.851 |

| 48.000 | 0.766 | 0.991 | 0.217 | 0.856 |

| 54.000 | 0.768 | 0.991 | 0.214 | 0.857 |

| 60.000 | 0.767 | 0.990 | 0.215 | 0.844 |

| AREA (pix) | VMAX | HIT | FALSE | BASE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.000 | 0.840 | 1.000 | 0.160 | 0.779 |

| 5.000 | 0.756 | 0.975 | 0.190 | 0.842 |

| 7.000 | 0.498 | 0.981 | 0.440 | 0.923 |

| 9.000 | 0.885 | 0.995 | 0.110 | 0.779 |

| REFL (dBZ) | VMAX | HIT | FALSE | BASE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25.000 | 0.802 | 0.990 | 0.180 | 0.840 |

| 30.000 | 0.796 | 0.989 | 0.185 | 0.838 |

| 35.000 | 0.790 | 0.982 | 0.181 | 0.809 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rigo, T.; Vilar-Bonet, F. A New Methodology for Detecting Deep Diurnal Convection Initiations in Summer: Application to the Eastern Pyrenees. Geomatics 2025, 5, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040072

Rigo T, Vilar-Bonet F. A New Methodology for Detecting Deep Diurnal Convection Initiations in Summer: Application to the Eastern Pyrenees. Geomatics. 2025; 5(4):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040072

Chicago/Turabian StyleRigo, Tomeu, and Francesc Vilar-Bonet. 2025. "A New Methodology for Detecting Deep Diurnal Convection Initiations in Summer: Application to the Eastern Pyrenees" Geomatics 5, no. 4: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040072

APA StyleRigo, T., & Vilar-Bonet, F. (2025). A New Methodology for Detecting Deep Diurnal Convection Initiations in Summer: Application to the Eastern Pyrenees. Geomatics, 5(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/geomatics5040072