The Mechanistic Causes of Increased Walking Speed After a Strength Training Program in Stroke Patients: A Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Intervention Protocol

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Musculoskeletal Modeling Pipeline

2.5. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Joint Kinematics and Kinetics Adaptations

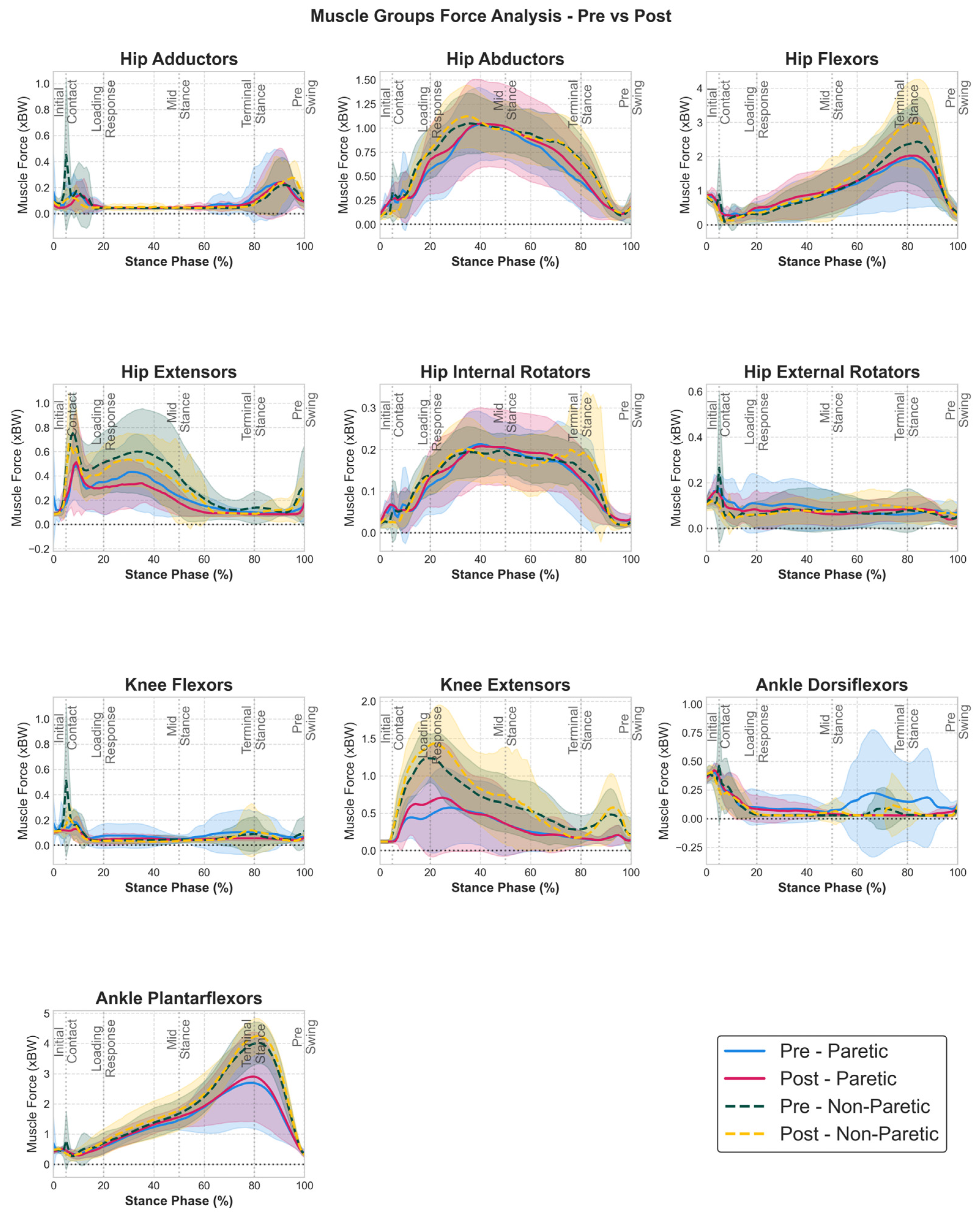

3.2. Muscle Group Force Adaptations

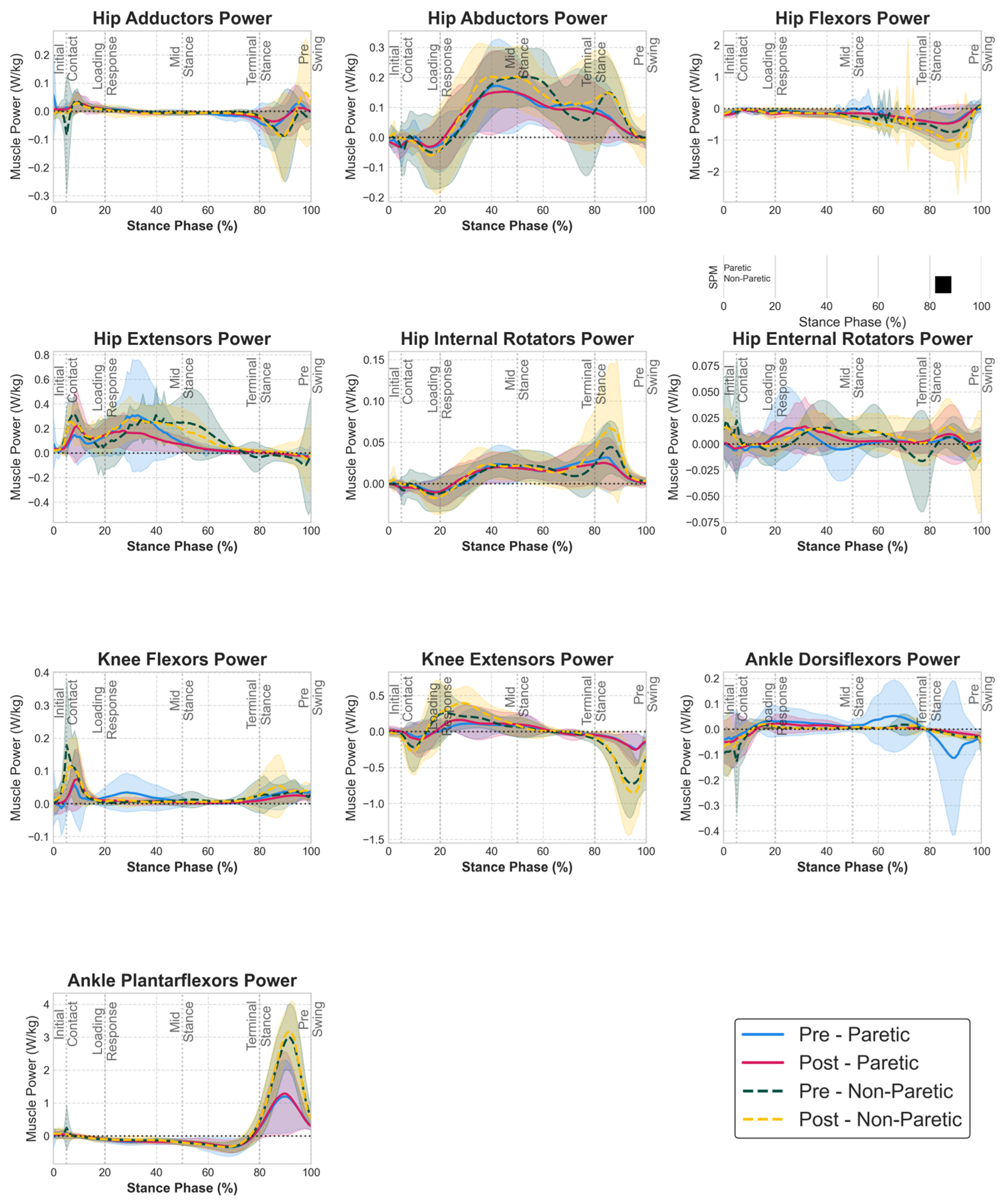

3.3. Muscle Group Power Adaptations

3.4. Muscle Work Capacity Adaptations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B.; Martins, S.; Sacco, R.L.; Hacke, W.; Fisher, M.; Pandian, J.; Lindsay, P. World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022. Int. J. Stroke 2022, 17, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, P.E.; Spaulding, S.J. Motor Control and Motor Learning: Implications for Treatment of Individuals Post Stroke. Phys. Occup. Ther. Geriatr. 2001, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelton, C.; McGill, K.; Campbell, P.; Todhunter-Brown, A.; Thomson, K.; Nicolson, D.J.; Cheyne, J.D.; Chung, C.; Dorris, L.; Gillespie, D.C.; et al. Perceptual Disorders After Stroke: A Scoping Review of Interventions. Stroke 2022, 53, 1772–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.H.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.T. Post-stroke cognitive impairment: Epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2, 80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parikh, S.; Parekh, S.; Vaghela, N. Impact of stroke on quality of life and functional independence. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2018, 8, 1595–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinear, C.M.; Lang, C.E.; Zeiler, S.; Byblow, W.D. Advances and challenges in stroke rehabilitation. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselhoff, S.; Hanke, T.A.; Evans, C.C. Community mobility after stroke: A systematic review. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2018, 25, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Francisco, G.E.; Zhou, P. Post-stroke hemiplegic gait: New perspective and insights. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 389766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Whitton, N.; Zand, R.; Dombovy, M.; Parnianpour, M.; Khalaf, K.; Rashedi, E. A Systematic Review of Fall Risk Factors in Stroke Survivors: Towards Improved Assessment Platforms and Protocols. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 910698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, F.M.; Macko, R.F.; Ryan, A.S.; Hafer-Macko, C.E. Cardiovascular Health and Fitness After Stroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2005, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.D.; Al Snih, S.; Stoddard, J.; Shekar, A.; Hurvitz, E.A. Obesity misclassification and the metabolic syndrome in adults with functional mobility impairments: Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2006. Prev. Med. 2014, 60, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarmatzis, G.; Giannakou, E.; Karagiannakidou, I.; Makri, E.; Tsiakiri, A.; Christidi, F.; Malliou, P.; Vadikolias, K.; Aggelousis, N. Effects of a 12-Week Moderate-to-High Intensity Strength Training Program on the Gait Parameters and Their Variability of Stroke Survivors. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flansbjer, U.B.; Miller, M.; Downham, D.; Lexell, J. Progressive resistance training after stroke: Effects on muscle strength, muscle tone, gait performance and perceived participation. J. Rehabil. Med. 2008, 40, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwansa, M.R.; Himalowa, S.; Kunda, R. Functional Gait of Patients with Stroke after Strength Training: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Int. J. Health Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, S.S.; de Carvalho, A.L.R.; de Almeida, K.O.; Neves, M.P.; Ribeiro Schindler, I.F.S.; Alves, I.G.N.; Arcanjo, F.L.; Gomes-Neto, M. Effects of isokinetic muscle strengthening on muscle strength, mobility, and gait in post-stroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2019, 33, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldema, J.; Jansen, P. Resistance training in stroke rehabilitation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 1173–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knarr, B.A.; Reisman, D.S.; Binder-Macleod, S.A.; Higginson, J.S. Understanding compensatory strategies for muscle weakness during gait by simulating activation deficits seen post-stroke. Gait Posture 2013, 38, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Patten, C.; Kothari, D.H.; Zajac, F.E. Gait differences between individuals with post-stroke hemiparesis and non-disabled controls at matched speeds. Gait Posture 2005, 22, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeau, S.; Gravel, D.; Arsenault, A.B.; Bourbonnais, D. Plantarflexor weakness as a limiting factor of gait speed in stroke subjects and the compensating role of hip flexors. Clin. Biomech. 1999, 14, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentiplay, B.F.; Adair, B.; Bower, K.J.; Williams, G.; Tole, G.; Clark, R.A. Associations between lower limb strength and gait velocity following stroke: A systematic review. Brain Inj. 2015, 29, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D.J.; Ting, L.H.; Zajac, F.E.; Neptune, R.R.; Kautz, S.A. Merging of healthy motor modules predicts reduced locomotor performance and muscle coordination complexity post-stroke. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 103, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, S.J.; Gray, V.L.; Knorr, S. Muscle Activation Patterns and Postural Control Following Stroke. Mot. Control 2009, 13, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsch, S.; Ada, L.; Canning, C.G. Lower Limb Strength Is Significantly Impaired in All Muscle Groups in Ambulatory People with Chronic Stroke: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.L.; Kautz, S.A.; Neptune, R.R. The influence of merged muscle excitation modules on post-stroke hemiparetic walking performance. Clin. Biomech. 2013, 28, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentiplay, B.F.; Williams, G.; Tan, D.; Adair, B.; Pua, Y.H.; Bok, C.W.; Bower, K.J.; Cole, M.H.; Ng, Y.S.; Lim, L.S.; et al. Gait Velocity and Joint Power Generation after Stroke: Contribution of Strength and Balance. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 98, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonsetler, E.C.; Bowden, M.G. A Systematic Review of Mechanisms of Gait Speed Change Post-Stroke. Part 2: Exercise Capacity, Muscle Activation, Kinetics, and Kinematics. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2017, 24, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajac, F.E.; Neptune, R.R.; Kautz, S.A. Biomechanics and muscle coordination of human walking: Part I: Introduction to concepts, power transfer, dynamics and simulations. Gait Posture 2002, 16, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.L.; Hall, A.L.; Kautz, S.A.; Neptune, R.R. Pre-swing deficits in forward propulsion, swing initiation and power generation by individual muscles during hemiparetic walking. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 2348–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.L.; Peterson, C.L.; Kautz, S.A.; Neptune, R.R. Relationships between muscle contributions to walking subtasks and functional walking status in persons with post-stroke hemiparesis. Clin. Biomech. 2011, 26, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbas, T.; Prajapati, S.; Ziemnicki, D.; Tamma, P.; Gross, S.; Sulzer, J. Hip circumduction is not a compensation for reduced knee flexion angle during gait. J. Biomech. 2019, 87, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.F.; Jakubowitz, E.; Pronost, N.; Bonis, T.; Hurschler, C. Predictive simulation of post-stroke gait with functional electrical stimulation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampire, N.; Roche, N.; Carne, P.; Cheze, L.; Pradon, D. Effect of botulinum toxin injection on length and lengthening velocity of rectus femoris during gait in hemiparetic patients. Clin. Biomech. 2013, 28, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbas, T.; Neptune, R.R.; Sulzer, J. Neuromusculoskeletal simulation reveals abnormal rectus femoris-gluteus medius coupling in post-stroke gait. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarmatzis, G.; Fotiadou, S.; Giannakou, E.; Kokkotis, C.; Fanaradelli, T.; Kordosi, S.; Vadikolias, K.; Aggelousis, N. Understanding Post-Stroke Movement by Means of Motion Capture and Musculoskeletal Modeling: A Scoping Review of Methods and Practices. BioMed 2022, 2, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwah, L.K.; Diong, J. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS). J. Physiother. 2014, 60, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leboeuf, F.; Baker, R.; Barré, A.; Reay, J.; Jones, R.; Sangeux, M. The conventional gait model, an open-source implementation that reproduces the past but prepares for the future. Gait Posture 2019, 69, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, A.; Dembia, C.L.; DeMers, M.S.; Delp, D.D.; Hicks, J.L.; Delp, S.L. Full-Body Musculoskeletal Model for Muscle-Driven Simulation of Human Gait. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 63, 2068–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thissen, D.; Steinberg, L.; Kuang, D. Quick and Easy Implementation of the Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure for Controlling the False Positive Rate in Multiple Comparisons. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2002, 27, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekutieli, D.; Benjamini, Y. Resampling-based false discovery rate controlling multiple test procedures for correlated test statistics. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1999, 82, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.L.; Malouin, F.; Dean, C. Gait in Stroke: Assessment and Rehabilitation. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 1999, 15, 833–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brincks, J.; Nielsen, J.F. Increased power generation in impaired lower extremities correlated with changes in walking speeds in sub-acute stroke patients. Clin. Biomech. 2012, 27, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvataneni, K.; Olney, S.J.; Brouwer, B. Changes in muscle group work associated with changes in gait speed of persons with stroke. Clin. Biomech. 2007, 22, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira-Salmela, L.F.; Nadeau, S.; McBride, I.; Olney, S.J. Effects of muscle strengthening and physical conditioning training on temporal, kinematic and kinetic variables during gait in chronic stroke survivors. J. Rehabil. Med. 2001, 33, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Neptune, R.R.; Zajac, F.E.; Kautz, S.A. Muscle force redistributes segmental power for body progression during walking. Gait Posture 2004, 19, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, D.A. Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Movement, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–370. [Google Scholar]

- Neptune, R.R.; Kautz, S.A.; Zajac, F.E. Contributions of the individual ankle plantar flexors to support, forward progression and swing initiation during walking. J. Biomech. 2001, 34, 1387–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.; Embry, A.; Perry, L.; Holthaus, K.; Gregory, C.M. Feasibility of lower-limb muscle power training to enhance locomotor function poststroke. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2015, 52, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostka, J.; Niwald, M.; Guligowska, A.; Kostka, T.; Miller, E. Muscle power, contraction velocity and functional performance after stroke. Brain Behav. 2019, 9, e01243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkers, I.; Delp, S.; Patten, C. Capacity to increase walking speed is limited by impaired hip and ankle power generation in lower functioning persons post-stroke. Gait Posture 2009, 29, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsdottir, J.; Recalcati, M.; Rabuffetti, M.; Casiraghi, A.; Boccardi, S.; Ferrarin, M. Functional resources to increase gait speed in people with stroke: Strategies adopted compared to healthy controls. Gait Posture 2009, 29, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alingh, J.F.; Groen, B.E.; Van Asseldonk, E.H.F.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Weerdesteyn, V. Effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions to improve paretic propulsion in individuals with stroke—A systematic review. Clin. Biomech. 2020, 71, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarmatzis, G.; Giannakou, E.; Gkrekidis, A.; Vadikolias, Κ.; Aggelousis, N. Clinical Validation Of Static Optimization During Post Stroke Gait. In Proceedings of the 28th Congress of European Society of Biomechanics, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 9–12 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Brief name | Progressive Pilates-based resistance training program |

| Why | To improve muscular strength, balance, and functional capacity in individuals with chronic stroke. Pilates-based resistance training emphasizes controlled movement, postural alignment and breath regulation. The progressive resistance approach aligns with established neuromuscular and neuroplasticity principles, facilitating strength gains and improved motor control post-stroke. |

| What (materials) | A range of Pilates equipment was used, including reformer towers, Wunda chairs, armchairs, barrels, Pilates rings, elastic bands, exercise balls, soft free weights, and Bosu platforms. Body weight was also used as resistance |

| What (procedures) | Each session included three phases: (a) Warm-up (5–10 min): Breathing exercises, postural alignment training, spine and limb mobility drills. (b) Main program (35–50 min): Individualized progressive resistance exercises targeting key muscle groups with specific dosage:• Hip extensors (e.g., leg press variations): 2–3 exercises • Knee extensors (e.g., seated leg extension on chair, sit ups): 2–3 exercises • Ankle plantar flexors (e.g., calf raises on reformer): 2–3 exercises • Hip flexors (e.g., standing hip flexion with bands): 2–3 exercises • Upper-body musculature (e.g., seated rows, chest press on reformer): 2–3 exercises. (c) Cool-down (5 min): Breathing, flexibility, and stretching exercises. Exercise intensity was progressively increased throughout the program based on Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE). |

| Who provided | Five qualified instructors administered the intervention. Each participant was supervised by two instructors during every session, ensuring safety, proper technique, and appropriate load progression |

| How | Delivered face-to-face, individually, with hands-on cueing, verbal feedback, and continuous real-time monitoring |

| Where | Conducted in a fully equipped Pilates studio suitable for resistance training and neurorehabilitation, with all necessary Pilates apparatus and safety supports |

| When and how much | Participants completed a 12-week program consisting of two sessions per week, for a total of 24 sessions. Each session lasted 45–60 min |

| Tailoring | Programs were personalized based on participants’ abilities, strength levels, balance capacity, and fatigue. Exercise selection, spring settings, resistance level, range of motion, and movement complexity were adjusted individually. Progressions were introduced when participants demonstrated safe and controlled execution |

| Modifications | The training load and exercise complexity were progressively increased over the 12 weeks. Should participants experience excessive fatigue, difficulty, or pain, exercises were modified by reducing load, adjusting range of motion, or selecting alternative apparatus |

| How well (planned) | Planned monitoring included session attendance logs, instructor documentation of exercise selection and resistance levels, and weekly tracking of perceived exertion scores to ensure progressive overload |

| How well (actual) | Participants were supervised continuously by two instructors to maintain exercise fidelity. Perceived exertion was systematically monitored using the Borg 1–10 scale, beginning with moderate intensity (5–6) in early sessions and progressing to high intensity (7–8, “really hard”) as tolerated |

| Muscle Group | Side | Pre (Mean ± SD) | Post (Mean ± SD) | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | p-Value (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ankle dorsiflexors | Non Paretic | 0.0013 ± 0.0007 | 0.0011 ± 0.0005 | [−0.0005, 0.0001] | −0.28 | 0.645 |

| ankle dorsiflexors | Paretic | 0.0018 ± 0.0029 | 0.0009 ± 0.0008 | [−0.0032, 0.0014] | −0.39 | 1 |

| ankle plantar flexors | Non Paretic | 0.0131 ± 0.0046 | 0.0129 ± 0.0059 | [−0.0023, 0.0020] | −0.02 | 1 |

| ankle plantar flexors | Paretic | 0.0134 ± 0.0066 | 0.0128 ± 0.0052 | [−0.0041, 0.0027] | −0.11 | 1 |

| hip abductors | Non Paretic | 0.0037 ± 0.0027 | 0.0032 ± 0.0019 | [−0.0022, 0.0013] | −0.18 | 1 |

| hip abductors | Paretic | 0.0023 ± 0.0014 | 0.0022 ± 0.0013 | [−0.0009, 0.0007] | −0.05 | 1 |

| hip adductors | Non Paretic | 0.0019 ± 0.0017 | 0.0019 ± 0.0014 | [−0.0004, 0.0005] | 0.04 | 1 |

| hip adductors | Paretic | 0.0014 ± 0.0011 | 0.0012 ± 0.0008 | [−0.0012, 0.0009] | −0.13 | 1 |

| hip extensors | Non Paretic | 0.0029 ± 0.0035 | 0.0015 ± 0.0011 | [−0.0034, 0.0007] | −0.5 | 0.645 |

| hip extensors | Paretic | 0.0013 ± 0.0010 | 0.0008 ± 0.0005 | [−0.0011, 0.0002] | −0.56 | 0.273 |

| hip external rotators | Non Paretic | 0.0004 ± 0.0007 | 0.0003 ± 0.0005 | [−0.0003, 0.0001] | −0.22 | 0.56 |

| hip external rotators | Paretic | 0.0004 ± 0.0005 | 0.0003 ± 0.0002 | [−0.0006, 0.0002] | −0.46 | 0.984 |

| hip flexors | Non Paretic | 0.0332 ± 0.0168 | 0.0421 ± 0.0189 | [0.0042, 0.0135] | 0.47 | 0.04 * |

| hip flexors | Paretic | 0.0225 ± 0.0155 | 0.0250 ± 0.0155 | [−0.0052, 0.0101] | 0.15 | 0.984 |

| hip internal rotators | Non Paretic | 0.0005 ± 0.0004 | 0.0005 ± 0.0004 | [−0.0003, 0.0002] | −0.1 | 1 |

| hip internal rotators | Paretic | 0.0003 ± 0.0002 | 0.0004 ± 0.0002 | [−0.0001, 0.0001] | 0.03 | 1 |

| knee extensors | Non Paretic | 0.0130 ± 0.0040 | 0.0141 ± 0.0062 | [−0.0016, 0.0037] | 0.19 | 0.984 |

| knee extensors | Paretic | 0.0049 ± 0.0033 | 0.0051 ± 0.0036 | [−0.0007, 0.0010] | 0.04 | 1 |

| knee flexors | Non Paretic | 0.0003 ± 0.0002 | 0.0002 ± 0.0001 | [−0.0001, 0.0001] | −0.29 | 0.984 |

| knee flexors | Paretic | 0.0004 ± 0.0005 | 0.0002 ± 0.0002 | [−0.0004, 0.0001] | −0.49 | 0.645 |

| Muscle Group | Side | Pre (Mean ± SD) | Post (Mean ± SD) | 95% CI | Cohen’s d | p-Value (FDR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ankle dorsiflexors | Non Paretic | 0.0006 ± 0.0004 | 0.0006 ± 0.0003 | [−0.0002, 0.0002] | −0.04 | 1 |

| ankle dorsiflexors | Paretic | 0.0021 ± 0.0029 | 0.0009 ± 0.0008 | [−0.0031, 0.0008] | −0.51 | 1 |

| ankle plantar flexors | Non Paretic | 0.0398 ± 0.0121 | 0.0414 ± 0.0097 | [−0.0031, 0.0063] | 0.14 | 1 |

| ankle plantar flexors | Paretic | 0.0176 ± 0.0136 | 0.0187 ± 0.0160 | [−0.0045, 0.0068] | 0.07 | 1 |

| hip abductors | Non Paretic | 0.0119 ± 0.0041 | 0.0126 ± 0.0049 | [−0.0012, 0.0026] | 0.14 | 1 |

| hip abductors | Paretic | 0.0089 ± 0.0050 | 0.0089 ± 0.0049 | [−0.0014, 0.0012] | −0.01 | 1 |

| hip adductors | Non Paretic | 0.0009 ± 0.0003 | 0.0012 ± 0.0011 | [−0.0004, 0.0011] | 0.43 | 1 |

| hip adductors | Paretic | 0.0010 ± 0.0006 | 0.0009 ± 0.0008 | [−0.0004, 0.0003] | −0.06 | 1 |

| hip extensors | Non Paretic | 0.0142 ± 0.0063 | 0.0137 ± 0.0050 | [−0.0038, 0.0027] | −0.09 | 1 |

| hip extensors | Paretic | 0.0101 ± 0.0079 | 0.0079 ± 0.0045 | [−0.0077, 0.0032] | −0.33 | 1 |

| hip external rotators | Non Paretic | 0.0008 ± 0.0008 | 0.0010 ± 0.0008 | [−0.0004, 0.0008] | 0.21 | 1 |

| hip external rotators | Paretic | 0.0007 ± 0.0006 | 0.0007 ± 0.0007 | [−0.0003, 0.0004] | 0.08 | 1 |

| hip flexors | Non Paretic | 0.0061 ± 0.0045 | 0.0078 ± 0.0072 | [−0.0009, 0.0042] | 0.26 | 1 |

| hip flexors | Paretic | 0.0052 ± 0.0049 | 0.0042 ± 0.0015 | [−0.0042, 0.0022] | −0.27 | 1 |

| hip internal rotators | Non Paretic | 0.0016 ± 0.0008 | 0.0020 ± 0.0013 | [−0.0001, 0.0008] | 0.32 | 1 |

| hip internal rotators | Paretic | 0.0015 ± 0.0009 | 0.0014 ± 0.0008 | [−0.0005, 0.0003] | −0.11 | 1 |

| knee extensors | Non Paretic | 0.0084 ± 0.0035 | 0.0114 ± 0.0046 | [0.0003, 0.0058] | 0.71 | 0.643 |

| knee extensors | Paretic | 0.0045 ± 0.0040 | 0.0055 ± 0.0047 | [−0.0010, 0.0030] | 0.21 | 1 |

| knee flexors | Non Paretic | 0.0024 ± 0.0013 | 0.0025 ± 0.0016 | [−0.0004, 0.0005] | 0.04 | 1 |

| knee flexors | Paretic | 0.0022 ± 0.0014 | 0.0015 ± 0.0009 | [−0.0016, 0.0003] | −0.52 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giarmatzis, G.; Aggelousis, N.; Giannakou, E.; Karagiannakidou, I.; Makri, E.; Tsiakiri, A.; Christidi, F.; Malliou, P.; Vadikolias, K. The Mechanistic Causes of Increased Walking Speed After a Strength Training Program in Stroke Patients: A Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach. Biomechanics 2025, 5, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040097

Giarmatzis G, Aggelousis N, Giannakou E, Karagiannakidou I, Makri E, Tsiakiri A, Christidi F, Malliou P, Vadikolias K. The Mechanistic Causes of Increased Walking Speed After a Strength Training Program in Stroke Patients: A Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach. Biomechanics. 2025; 5(4):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040097

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiarmatzis, Georgios, Nikolaos Aggelousis, Erasmia Giannakou, Ioanna Karagiannakidou, Evangelia Makri, Anna Tsiakiri, Foteini Christidi, Paraskevi Malliou, and Konstantinos Vadikolias. 2025. "The Mechanistic Causes of Increased Walking Speed After a Strength Training Program in Stroke Patients: A Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach" Biomechanics 5, no. 4: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040097

APA StyleGiarmatzis, G., Aggelousis, N., Giannakou, E., Karagiannakidou, I., Makri, E., Tsiakiri, A., Christidi, F., Malliou, P., & Vadikolias, K. (2025). The Mechanistic Causes of Increased Walking Speed After a Strength Training Program in Stroke Patients: A Musculoskeletal Modeling Approach. Biomechanics, 5(4), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomechanics5040097